Introduction

In one of his essays, Literature and Totalitarianism, Orwell (1941) cogently asserts that:

The totalitarian state . . . cannot allow the individual any freedom what ever. When one mentions totalitarianism, one thinks immediately of Germany, Russia, Italy, but I think one must face the risk that this phenomenon is going to be world-wide. (para. 3)

This assertion seems a prediction from the 1940s, because Orwell warns us about the spread of totalitarianism around the world. With it, the individual’s freedom to think and to act is restricted. Nowadays, thought and behavior control creates an ideology and always tries to rule our emotional and behavioral lives. This gives rise to an artificial world in which individuals have the criteria to compare themselves with the outside world through uniform patterns devised for massive control.

In this article, we extrapolate the Orwellian idea of thought and behavior control to the execution of disciplinary power by means of language. In line with this, we turn again to Orwell and the newspeak as a language created by the State that appears in his masterpiece 1984, to point out that actors who hold control create a language to prevent critical creative thought.

We report here on a critical discourse study about the use of the discourse of standard English to exercise disciplinary power through English language testing practices. Our study focuses on the fact that applicants to some international scholarships must hold certified English proficiency through tests. The scholarships under examination are those offered by the alliance between the Association Internationale des Étudiants en Sciences Économiques et Commerciales (AIESEC) and Instituto Colombiano de Crédito Educativo y Estudios Técnicos en el Exterior (ICETEX).

Research Problem

The research problem stems from the premise that the concession of AIESEC-ICETEX scholarships is determined by social orders (Fairclough, 2001). Such concession is mediated by the requisite of certified English proficiency as the result of profiling candidates by means of school discipline. Thus, the problem has a three-fold dimension: The first dimension, scholarships as exercise of disciplinary power in Colombian schooling, relates to the role that disciplinary power plays to reach the social ends attributed to school. In Colombia, disciplinary power has been exercised differently in accord with three pedagogical models that have permeated school, namely the Lancasterian school, the Enseñanza simultánea (simultaneous teaching), and the active school (Restrepo-Mejía as cited in Saldarriaga, 2003). From the pedagogical models in question, the second one deserves special attention. This is because awarding students for their performance becomes a strategy for school pupils to internalize their duties without being punished (Saldarriaga, 2003) and upgrade their virtues by emulating prodigious models that awaken the good (Restrepo-Mejía as cited in Saldarriaga, 2003). In this framework, school awards have taken different shapes such as honorable mentions, exams exemptions, and scholarships. Scholarships are used for honoring students who demonstrate meeting the social ends of schooling.

The second dimension, traces of discipline in ICETEX-mediated grants, calls for a contextualization about what ICETEX is and what it does. ICETEX is an agency of the Colombian education system whose aim is to promote access to and permanence in university programs of low-income students by means of offering financing mechanisms and administration of own and third-party resources, and scholarships from national and international supporting agencies (Law 1002, 2005). It is a common requisite for applicants-to be granted an international scholarship-to demonstrate intermediate or high English proficiency levels through tests based on the Common European Framework (CEFR). Those tests are known for promoting a standard variety of the English language in social practices such as education, work, and traveling (Educational Testing Service, n.d.; International English Language Testing System, n.d.; University of Michigan, n.d.). This feature makes them become deemed as valid tests, constituting these tests’ creators as the access point of the English language testing system. By access point, we refer to “systems of technical accomplishment or professional expertise that organize large areas of the material and social environments in which we live today” (Giddens, 2013, p. 27). To illustrate this dimension, there are alliances mediated by ICETEX that offer scholarship programs for Colombians in diverse countries. It is paradoxical that, for instance, even though Peru is not officially an English-speaking country, the requisite of certified English proficiency is demanded in the scholarship programs. Those programs ask for mastery of the English language.

The third and last dimension is the requisite of certified English in AIESEC-ICETEX scholarships as a disciplinary component. It relates to the two previous dimensions and guides our attention to a troublesome statement of AIESEC scholarship programs that corroborates the requisite of certified English through valid tests: “The requisite of English is necessary even though the practice takes place in a Spanish-speaking country or another” (ICETEX & AIESEC, 2011; 2012; 2013a; 2013b; 2014, para. 20). AIESEC is a youngsters’ non-profit organization led by young people from 126 countries; it is acknowledged by UNESCO and sponsored by multinational corporations worldwide (e.g., Apple, Nike, Electrolux, Accenture, and Nokia, among others; AIESEC, n.d.-c). It claims to advocate for peace and human potential development, to contribute to the development of associated countries and their people, and to commit to international cooperation (AIESEC, n.d.-c). In addition, its mission is to serve as an international platform and global learning environment for youngsters to discover and develop their leadership potential in order to impact positively on society (AIESEC, n.d.-c). This makes us infer that the goals of AIESEC and the access point in question intersect. Both promote economic and social practices such as working, studying, and traveling abroad. In this intersection, the access point certifies a person who can use standard language varieties for being competent in these practices.

One point that relates to the social and political agendas behind AIESEC-ICETEX scholarship program is made by Shohamy (2017) when she states that tests are powerful in the sense that “they can lead to differentiation among people and for judging them” (p. 444). In the case of AIESEC-ICETEX scholarships, language tests classify people so as to determine who is proficient in the standard English varieties under the benchmarks imposed (i.e., CEFR). This functioning of tests already portrays a social interest: fostering roles in society (e.g., so-called bilingual workers). By classifying people into their language proficiency beforehand, language tests already objectivize (Gruenfeld et al., 2008) test-takers at the access point. The problematization of the requisite in question occurs within a tensional social space (school) and its processes (schooling), more explicitly in its disciplinary practices and components.

The statement about the existence of a problem made so far, made us pose the question that guided the study reported on in this article: How does the discourse of standard English exercise disciplinary power in AIESEC-ICETEX scholarships concessions?

Theoretical Considerations

The theoretical considerations for this study stem from a discussion about the relationship between two constructs: school as a disciplinary field and the English language curriculum as a disciplinary micro field. One main argument of such relationship is that school is a field in which different discourses dispute and/or adhere to one another, forging disciplinary practices that aim to create useful and docile subjects (Foucault, 1975/1977, 1975/2002).

The former construct, school as a disciplinary field, from Bourdieu’s (1989) field theory, leads us to conceive school as a social space where actors relate to each other mediated by forms of capital. In addition, the social actors’ relationships and practices within the field of school can be of various types; for instance, hierarchical, that imply domination or submission, or horizontal, that imply equality. School as a social space has been constituted as a field where objectification processes construct amenable human beings by means of disciplinary power. Students, teachers, principals, secretaries, coordinators, and security guards, among others, participate in the power relations of school (van der Horst & Narodowski, 1999). They are responsible for the embodiment of school power dynamics, yet hardly ever take part in their decisions. On the other hand, other social actors such as politicians, entrepreneurs, technocrats, religious leaders, and so on, influence the delineation of policies and enactment of laws that determine school demands. However, school social ends are not the result of a wide consensus.

Turning our attention to school discipline, we can say that it has abandoned the most coercive mechanisms, for instance, physical punishment, and has adopted subtler techniques to make schools objects of scientific disciplines and dividing practices (Foucault, 1988). Objectification refers to “an instrument of subjugation whereby the needs, interests, and experiences of those with less power are subordinated to those of the powerful, and this facilitates using others as means to an end” (Gruenfeld et al., 2008, p. 111). Thus, school disciplines students in order to achieve its social, economic, and political ends. In this perspective, Foucault’s (1975/2002) idea of means of correct training-hierarchical observation, normalizing punishment, and examinations-constitute a guarantee of order and control.

Framed in the aforesaid school dynamics, AIESEC-ICETEX scholarships embody the discursive construction of the good student, someone who subsequently would become a good applicant and later, a good worker. This assertion is based on the fact that applicants to these scholarships must adjust to selection criteria, for example, grade point average, and academic background (i.e., having a major in offered areas; ICETEX, n.d.-a). As for the concern of this study, the required so-called valid English language tests (ICETEX, n.d.-a) are bred within the disciplinary micro-field of English language curriculum.

The second construct, the English language curriculum as a disciplinary micro-field, is based on our understanding of curriculum as a net of force relations (Bourdieu, 1995, as cited in Rincón-Villamil, 2010) that is set due to domination and subordination practices. In this light, (social) curriculum actors vested with major capital are dominant and, thereby, establish the norms of the field (orthodoxy). In turn, a group of dominated actors uses arguments to overthrow the dominants (heterodoxy), and another group will use a popular discourse with no major impact on the field (doxa; Rincón-Villamil, 2010). In Colombia, orthodoxy in the English language curriculum is represented within social actors such as publishing houses, international governmental organizations, and cultural institutes (e.g., the British Council). This is because these corporations set the access point (Giddens, 2013) of the English language testing system.

In turn, alternative but isolated efforts of research groups and teacher-researchers constitute heterodoxy. They have put emphasis on how language policies, cultures, policy-makers, and practitioners constitute power relations, which lead to resistance, subjugation, privilege, and alienation in the Colombian educational system (e.g., Escobar-Alméciga, 2013; Forero-Mondragón, 2017; Guerrero, 2010; Guerrero-Nieto & Quintero-Polo, 2009). Yet, their efforts do not echo as hard as the dominant actors do because they are constrained by dominant discourses exclusion systems (Foucault, 1981). Resultantly, heterodox discourses do not adhere easily to others in the English language curriculum disciplinary micro-field.

In the third level, the doxa is represented in the opinions of parents/caretakers, teachers, students, and so on, who welcome, apprehend, and reproduce the discourses from the orthodoxy. These opinions revolve around opportunities for social mobility and personal and professional growth that are generally associated with English learning (Guerrero, 2010; Spring, 2008). They are constructions of discursive representations that sell the wonders of English to access an imagined community of English speakers (Guerrero, 2010). Although inside the doxa there also exists resistance towards dominant discourses, dominant social actors’ agendas are stronger owing to an imposed set of benchmarks and discourses.

Regarding the concept of standard English, we focus on its twofold dimension: ideological (Milroy, 2001; Razfar, 2012) and discursive (Fairclough, 2001). As an ideology, standard English relates to language and a capitalist belief system. In this vein, standard English is functional since it fosters effective communication for economic purposes (Milroy, 2001). Similarly, as it unifies the interactions of people, it has been useful for the consolidation of political systems like nation-states at the expense of marginalized groups and their so-called dialects (Razfar, 2012). On the other hand, standard English as a discourse, that is, language as a social practice (Fairclough, 2001), implies that dominant groups such as bourgeois classes represent social reality aligning it with their interests by means of language. Both ideology and discourse relate to one another in the sense that the former uses the latter as a mediator in order to restrict access to discursive practices.

Resultantly, the discourse of standard English emerges from the assumption that standard English enjoys prestige for its uniformity (Milroy, 2001) concreted in “few differences in grammar between them” (Cambridge University Press, n.d., para. 1). Finally, this characterization is not exhaustive but allows us to identify the main social function of said discourse: ensuring the quality of English language teaching, learning, and assessment.

Method

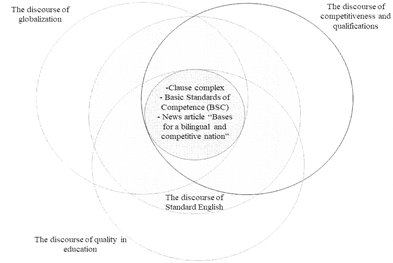

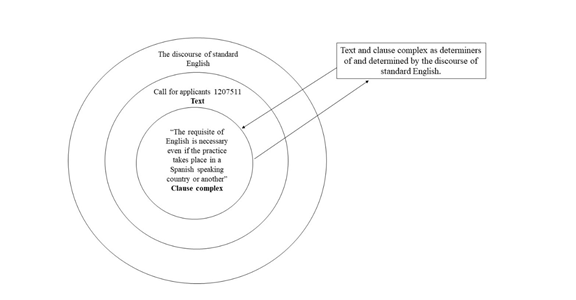

Our study was developed following Fairclough’s (2001) critical discourse analysis model. Said model is divided into three stages, namely: description, interpretation, and explanation. Description deals with the analysis of formal features of the text (Fairclough, 2001). By text, we refer to a product of discourse (Fairclough, 2001; Martín-Rojo, 1996) that in this study owns a linguistic nature. In the study reported here, description entailed two phases. First, we analyzed five texts (calls for applications) considering aspects such as their authors, target readers, and channels of distribution. Second, we analyzed a clause complex extracted from one of these calls. A clause complex is a “grammatical construction consisting of two or more (simplex) clauses” (Andersen & Holsting, 2018, The Clause Complex in IFG section, para. 1). Here the clause complex in question was deemed as a fragment of a text, that is, the call for applications labelled 1207511. Figure 1 presents the relationship among discourse, text, and clause complex in this study.

Note. Own elaboration.

Figure 1 Relationship Among Discourse, Text, and Clause Complex in This Study

We conducted the aforementioned descriptive analysis using a language approach devised by linguist Michael Halliday (1996): systemic functional linguistics (SFL). The reason behind this choice was that it permitted this critical discourse study to cast understanding on how language as a social practice (discourse) exercises disciplinary power. In this vein, we identified lexicogrammar in SFL terms as components that evidenced power exercise. These components were interpersonal relationships between authors and readers of the corpus (e.g., a hidden imperative mood, obligation modality, and impersonal construction); and the performance of processes among participants under certain circumstances (i.e., transitivity), for instance, relational processes of the attributive type (Flowerdew, 2013).

The analytical stage interpretation dealt with the inferences drawn from the first analytical stage as for the relationships among social actors in the clause complex. Interpreting these relationships required analyzing two features: social orders and interactional history (Fairclough, 2001). Both social orders and interactional history constituted our interpretive toolbox, which led us to wonder about what was not in black and white in the clause complex: the impersonal forms employed that hid the actors responsible for uttering the peremptory character of certified English in AIESEC-ICETEX scholarships. This situation called for a tracking of other texts in pursuit of wider understanding in this respect: the booklet Basic Standards of Foreign Language Proficiency (Henceforth, Booklet 22; Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN], 2006) and the article “Bases for a Bilingual and Competitive Nation” from the newsletter Altablero, Issue 37 (Henceforth, newsletter article; MEN, 2005). The former was chosen because it enforced so-called valid English certifications as part of the discourse of standard English across the Colombian educational system when ICETEX and AIESEC produced the clause complex (2011). The latter was selected as it justified the standardization of English language education in Basic Standards of Competence. Making these choices, we sought to characterize the representations of English as a gatekeeper to a globalized economy in which the social actors in the clause complex (i.e., applicants and offerors) participated either in the processes of production, distribution, or consumption (Fairclough, 2001) of the discourse of standard English.

The explanatory stage implied linking the practices of production, distribution, and consumption unveiled in the previous stage to their social and historical conditions (Fairclough, 2001). In linking both standard English discursive practices and conditions, we resorted to the theoretical considerations presented in the previous section. Accordingly, this analytical stage aimed to argue the social implications of the findings from the descriptive and interpretive analytical stages.

Findings

Our study aimed at shedding light on how the discourse of standard English exercised disciplinary power in five calls for applications of the alliance AIESEC-ICETEX from 2011 to 2014. Informed by a socio-constructivist ontology (Constantino, 2008) and an interpretive epistemology (Firmin, 2008), we analyzed these calls for applications adapting Fairclough’s (2001) analytical model. In the following lines, we account for the most significant findings.

The Requisite of Certified English: Interpersonal Relations Without Persons

The first stage (i.e., description) was centered on analyzing the authorship, readership, and relation authorship-readership of the corpus. Its purpose was to describe the interpersonal relationships between the social actors embedded: offerors and applicants. For analyzing said interpersonal relationships, we drew from Halliday’s SFL view on tenor and transitivity.

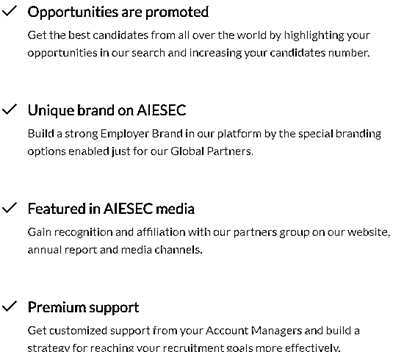

Regarding authorship of the corpus, we labeled ICETEX and AIESEC as first-hand authors; in other words, those that embodied authorship in the first place for being the scholarships offerors. However, texts are cause and effect of other texts; therefore, identifying a definite list of authors was not our purpose. Examining the social mission of the first-hand authors, we noted that the Colombian state agency and the nonprofit organization shared some values and visions of the world. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate this assertion.

Figure 2 is a photo taken from a banner at one ICETEX office in Bogotá, Colombia. It contains terms such as breaking boundaries, high quality education, internships abroad, administration funds, higher education funding, and growth, and so on. As an agent of global education, ICETEX aims to spread a view of a globalized world where investing in education to develop human capital for economic growth (Spring, 2008) is a way to access better opportunities.

Figure 3 portrays a screenshot taken in October 2019 from AIESEC Colombia’s Facebook post that seeks to promote AIESEC calls for applications. As evidenced in its content, AIESEC also fosters human development in a globalizing world, which responds to its social mission, that is, serving as a platform for young people to develop their potential in a global learning environment (AIESEC, n.d.-c). This post shows that AIESEC aims to be a gatekeeper to the global market. Multinational corporations are depicted as organizations that aid senior university students and professionals to develop their potential. Likewise, there is a cultural component that seems to attract applicants: the chance to be immersed in a different culture. This feature corresponds to globalization.

According to Spring (2008), the global market searches for immigrants willing to be part of brain circulation, in other words, going abroad and returning to their countries to talk about the benefits they gained when traveling and working overseas. In this light, AIESEC promotes a globalized world that allows people to upgrade their professional skills and be immersed in other cultures (AIESEC, n.d.-a). Consequently, the alliance ICETEX-AIESEC nurtured the global market by calling people to be interns and workers overseas. Congruently, when they allied from 2011 to 2014, their goal was a common ground. They opened five calls for applications labeled numerically on the website of ICETEX (see Table 1).

Table 1 AIESEC-ICETEX Calls for Applications

| Year | Name of the call for applications |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 1207511 |

| 2012 | 1200112 |

| 2013 | 1200213 |

| 2013 | 1200314 |

| 2014 | 1200414 |

Note. From ICETEX (n.d.-b)

The applicants were constructed as passive social actors because this corpus targeted people of certain profiles. For example, call 1200112 was directed to recent university alumni and senior students in university programs such as “language teaching or modern languages, administration, business, marketing and sales, industrial engineering, and education sciences” (ICETEX & AIESEC, 2012, our translation). People willing to participate in these calls also should have shared some values. Call 1200213 states that “the program is especially designed for youngsters with a global vision and projection who desire to discover and develop their potential to have a positive impact on society and, besides, have aptitudes and experience in the exercise of leadership” (ICETEX & AIESEC, 2013a, our translation and emphasis). Accordingly, values like global vision, development of potential to have a positive impact, and leadership had to be met by the applicants.

Applicants to these grants had to fulfill other requirements, for example holding certified English proficiency. In other words, their possibilities to be awarded depended on the compliance of preset profiles. Because of our research interest, we delved into how this passive role was subtly set in the requisite of English expressed in the clause complex the requisite of English is necessary even if the practice takes place in a Spanish-speaking country or another (ICETEX & AIESEC, 2011, 2012, 2013a, 2013b, 2014).

Considering that the first-hand authors’ objects intersected in the production of five calls for applications and the passive role readers of the calls for applicants, we focused ulterior analysis on a clause complex (i.e., the one requiring certified English proficiency). This analysis emphasized transitivity and the contextual parameter tenor according to SFL. Transitivity refers to language users’ codification of their “experience of the processes of the external world, and of the internal world of [theirs]” (Halliday, 1973, p. 134). Therefore, transitivity entails “the different types of processes involved, their relations to the roles of the participants and how these processes, roles and circumstances relate to one another” (Flowerdew, 2013, p. 17). In SFL, six are the processes types that account for transitivity: relational, mental, material, existential, behavioral, and verbal (Flowerdew, 2013). In order to account for the kind of process involved in the clause complex (i.e., the requisite of English is necessary even if the practice takes place in a Spanish-speaking country or another), it was necessary to identify its lexicogrammar elements.

The first element to describe was the number of clauses making up the clause complex. In this vein, this clause complex is originally made up of two clauses that are joined by a conjunction. Table 2 displays this.

Table 2 Clauses That Constitute the Clause Complex of Analysis

| The requisite of English is necessary | even if | the practice takes place in a Spanish-speaking country or another. |

| Clause 1 | Conjunction | Clause 2 |

Note. From ICETEX (n.d.-b, our translation)

From the previous taxonomy, we arrived at two conjectures. First, Clause 2 depends on Clause 1. In SFL terms, Clause 1 is superordinate and Clause 2, a subordinate one. Regarding semiotic implications, we inferred that the requisite of English (Clause 1) is compulsory regardless of the circumstances. Second, both nominal groups “the requisite” and “the practice” are carriers of attributes present in the adjectival groups “necessary,” “Spanish-speaking,” and “another.” For this reason, the transitivity processes carried out in the clause complex are relational of the attributive type. By relational we refer to processes of existing and being (Flowerdew, 2013). In turn, attributive means the process of relation between carrier and attribute. In a bigger picture, Clause 1 attributes a condition of being to Clause 2 in the sense that the content of Clause 2 does not affect the compulsory nature of Clause 1, as suggested before.

As evidenced so far, the analysis on transitivity did not reveal signs of activeness regarding the applicants. In fact, candidates applying to these scholarships had to certify their English proficiency if they wanted to apply. The preset passiveness of the readers of the clause complex was more explicit when the contextual parameter tenor was examined. Tenor is linked with “the relations of the participants in the text” (Flowerdew, 2013, p. 12). These relations are mediated by lexicogrammar elements such as mood, modality, and person. The first of them is related to whether a clause is imperative or indicative; the second one, to modal verbs or phrases; the third, to first, second, or third person, either singular or plural. Table 3 illustrates tenor as for the clause complex in question.

Table 3 Tenor in the Clause Complex Under Analysis

| Lexicogrammar item | Type |

|---|---|

| Mood | Indicative |

| Modality | Obligation |

| Person | Third person singular |

Table 2 shows that the clause complex is a statement, which makes it indicative. However, in semiotic and practical terms the function of this statement transcends indication because it ends up mandating the requisite of English. Second, the clause complex does not include any modal verb of obligation. The adjective “necessary” accounts for that, though. Finally, the third person is represented in two nominal groups: “the requisite” and “the practice.”

The textual analysis let us understand that the requisite of certified English is completely compulsory, which is an index of hidden intentions in the calls for applications. Likewise, the impersonal forms employed in the clause complex (e.g., the above-mentioned nominal groups) indicate that the social actors that participate in the social practice of AIESEC-ICETEX scholarship concessions are not relevant for meaning-making and then, are suppressed. What is the aim of this discursive strategy? Why do not authors and readers, that is, offerors and applicants appear in black and white?

The Entangled Discourse of Standard English

The prior textual analysis permitted us to realize that the relationship authors-readers in AIESEC-ICETEX calls for applications implies activeness and passiveness. First-hand authors (AIESEC and ICETEX) determined the role that readers (applicants) had to comply with: meeting requisites such as age, profession, global values, cities of residence, and certified English through so-called valid tests, this latter being our research concern. Nonetheless, that analytical stage fell short in unveiling the discursive production of the clause complex chosen for in-depth examination. Said analysis, which corresponds to the interpretive stage, would subsequently help shed light on the political, social, and economic agendas embedded in the requisite of English.

Interpreting the discursive production of the clause complex was relevant to characterize the representation of English as something testable, uniform, and functional for the global market (Fairclough, 2001; Milroy, 2001; Spring, 2008) that we label as the discourse of standard English. Moreover, the interpretive stage led us to understand the entanglement among this discourse and other discourses such as globalization, quality in education, and competitiveness and qualifications. Such inferences emerged from an exercise that consisted of setting intertextual relations between the clause complex and two other texts.

Tracing the inexorable and unilateral requisite of certified English in AIESEC-ICETEX scholarships, we established intertextual relations with two texts of a normative character, namely, the Booklet 22 (MEN, 2006) and the newsletter article (MEN, 2005). The reason why we selected these two texts is they derived from a Colombian state policy that circulated the discourse of standard English: The National Bilingual Program (MEN, 2006).

The interpretive stage cast light on the entangled nature of the discourse of standard English. Put simply, the analysis of the booklet and the news article evidenced that such a representation of reality, practices, and actors takes part in a discursive entanglement represented in Figure 4.

Figure 4 presents the discourse of standard English as the cause and consequence of other discourses, that is, the discourse of globalization, the discourse of competitiveness and qualifications, and the discourse of quality in education. This entanglement enables the discourse of standard English to construct social realities in which students are passive actors both in the learning process and in the labor market (e.g., when they apply to AIESEC-ICETEX scholarships). Hereunder, fragments from Booklet 22 and the newsletter article will be used to illustrate our argumentation.

The Discourse of Globalization

The Colombian Ministry of Education conceived the National Bilingual Program as a measure to “reach citizens capable of communicating in English in order for them to able to insert the country in the processes of universal communication, global economy, and cultural opening with internationally comparable standards” (MEN, 2006, p. 6, our translation and emphasis). The phrases in italics let us gain understanding of the ends of the program and the role English language education should play: developing communicative competences in order to sell the idea of English as the key to access the wonders of the modern world (Guerrero, 2010). For the Ministry, learning English equals becoming bilingual: being a competent English user allows citizens to be part of global market practices such as knowledge economy, social mobility, and human capital development (Spring, 2008). In sum, the Ministry of Education privileges a view of bilingualism as a synonym of English learning given that English is the language of global commerce.

Yet, what varieties of English fit the aforementioned characterization? As discussed in the introductory section, so-called valid language tests (i.e., TOEFL, MET, and IELTS) evaluate standard English varieties, those that permit social mobility. This framework lets us infer that the discourse of globalization assigns to the discourse of standard English a purpose that justifies processes such as standardized testing and other reified forms of standard English (e.g., textbooks, materials, and standards). In other words, the discourse of globalization answers the why one should learn these uniform, prestigious, and functional language varieties (Milroy, 2001). A question emerges: How does the discourse of globalization ensure standardized language practices? A second discourse comes into play: the discourse of quality in education.

The Discourse of Quality in Education

Making sure standard English is learned and used in social spheres, including school and industry, is the role the discourse of quality in education plays. For achieving this, Booklet 22 adopted a set of “internationally comparable standards” (MEN, 2006, p. 6): The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, and Assessment (Council of Europe, 2001). Overall, the CEFR served the purpose of establishing a standardized conception of language that should favor communication based on an array of communicative competences (i.e., linguistic, pragmatic, and sociolinguistic) that are attained through a gradual learning process divided into levels of proficiency (MEN, 2006). How is this attainment validated?

The Ministry of Education started to implement CEFR-based testing in the educational system, that is, school (MEN, 2006), which took shape in statewide examinations. Such process began in 2005 when the Ministry asked university senior students (those with majors not related to languages) to take “an English test, within the framework of Exámenes de calidad de la educación superior [which was] aligned with the framework of reference and goal proposed” (MEN, 2005, “Educación superior y manejo del inglés” section, para. 3, our translation). In the case of senior students from language-related majors, they had to take the First Certificate in English (MEN, 2005).

The former arguments constitute the basis for the assertion that school is set up as a hotbed for inserting Colombian students into the global market through the platform AIESEC. In this school machinery (Varela & Álvarez-Uría, 1991), certified standard English (B2 level, according to the CEFR) is one of the gatekeepers along with the compliance of other characteristics. Together, these requisites are manifestations of the discourse of quality in education as they construct the type of subjects the global economy expects: competent and qualified individuals. Precisely, this construction is due to the intervention of another discourse, that is, the one of competitiveness and qualifications.

The Discourse of Competitiveness and Qualifications

We have already argued that the discourse of standard English is a subsidiary of the discourses of globalization and quality in education, which does not mean the former is merely an effect of the other two. On the contrary, it is a two-way constitution, that is, the discourse of standard English also reinforces the representations of society the other two discourses circulate. In this light, being part of a set of requisites, certified proficiency in standardized English testing became a qualification that allowed AIESEC-ICETEX applicants to compete with others in order to obtain a scholarship. This subscribes to the discourse of competitiveness and qualifications.

English learning is seen as a result of the banking education model (Guerrero & Quintero, 2016). Students are conceived as containers that are filled with knowledge: “many standards are repeated, strengthened and deepened in different grades . . . in accordance with the cognitive level of students” (MEN, 2006, p. 16, our translation and emphasis). Accordingly, the Ministry of Education constructs students as passive actors, that is, consumers of imposed knowledge. Far from being a coincidence, the forging of passiveness in students, who could become applicants to AIESEC-ICETEX scholarships, is the fertile ground for materializing the discourse of competitiveness and qualifications.

The Discourse of Standard English and Disciplinary Power in AIESEC-ICETEX Scholarships: Language Does Things

AIESEC-ICETEX selected applicants who fulfilled the needs of the global market. Notwithstanding, we have not explained how this platform worked. The explanation to this is that AIESEC-ICETEX permitted the consolidation of hiring practices of corporations that sponsor AIESEC. This inference emerged from analyzing five testimonies from AIESEC Colombia alumni.1 As follows, we will broach two voices of AIESEC former members asking the question “how is your life after AIESEC?” Their names were replaced by the nicknames A4 and A2.

Being responsible for managing the young strategies of the World Economic Forum sounds extremely challenging but after one has passed through an organization such as AIESEC, I feel I have enough capacities. (A4, Interview, our translation and emphasis)

When the interviewee affirmed having enough capacities to manage a great task at work, a manifestation of the discourse of competitiveness and qualifications was evident in the word “capacities.” In this sense, A4 deemed AIESEC as a gatekeeper of better professional opportunities. This testimony led us to identify two implicatures: (a) This individual must have met all the requisites demanded (see the corpus under analysis), including English proficiency; (b) this person enrolled in the World Economic Forum due to being selected in an AIESEC program. The former conjectures were ratified when we analyzed the voice of alumnus A2.

Currently. I have just moved to Malaysia. I am working in a company called Mindvalley which is in Kuala Lumpur. For those people who do not know the organization, apart from being a global partner of AIESEC, it is a company that works in the educational sector. (A2, Interview, our translation and emphasis)

Interestingly, A2 highlighted the partnership between AIESEC and sponsors, evidencing that for this alumnus, taking part of AIESEC meant a job opportunity in one of AIESEC’s premium sponsors (i.e., Mindvalley). By premium sponsors, we refer to enterprises that can obtain a higher status and more privileges with AIESEC, as depicted by an excerpt taken from the webpage (Figure 5).

The testimonies and Figure 5 confirm that AIESEC is a labor platform that connects its members to work opportunities in international corporations. For this to happen, applicants must meet different requisites, English proficiency being the one of interest here. Put simply, AIESEC scholarships, including those co-offered with ICETEX, aim to attract high-quality professionals and senior university students for easing recruitment processes for its sponsors.

AIESEC-ICETEX scholarships concession had a discursive constituent that consisted of the entanglement of the discourses of globalization, quality in education, and competitiveness and qualifications. However, the selection of candidates did not only occur at the moment of applying. Rather, it was one of the last steps for materializing the foregoing discursive entanglement. Where did it all start?

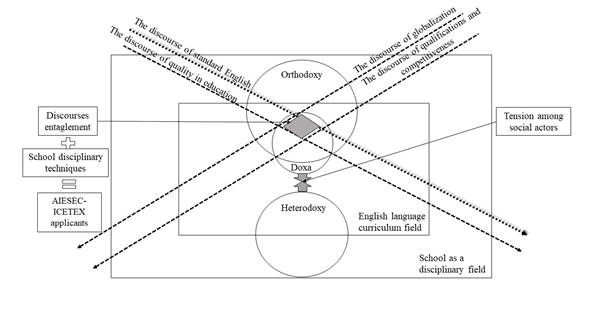

As posited in the theoretical considerations section, school is a disciplinary field where tensional forces (social actors) struggle and/or adhere to one another in pursuit of the spread of their interests in the social spheres. In doing so, school disciplinary practices such as exams and honor-based discipline (i.e., honor rolls, payment exemptions, and grants) are techniques employed to construct docile and utile subjects that meet those interests. In this field, there are micro-fields; for example, the English language curriculum. Vested with its own tensions, this micro-field is governed by dominant social actors that constitute the orthodoxy; among these are CEFR-oriented publishing houses, testing enterprises, governmental agencies, and cultural institutes (e.g., the British Council and the U.S. Information Agency), and materials designers. Orthodoxy circulates the discourse of standard English through standardized forms of language teaching, learning, and assessment. These manifestations are contested by heterodox actors and consumed/reproduced by the doxa (Bourdieu, 1986). See this tensional relationship among social actors in Figure 6.

In Figure 6, the micro-field of English curriculum is crossed by four discourses, namely: the discourse of globalization, the discourse of competitiveness and qualifications, the discourse of quality in education, and the discourse of standard English. This affirmation departs from the fact that Booklet 22 universalize the communicative competences and their evaluation schoolwide. Nevertheless, these discourses do not spread their representations of social reality and social actors separately. On the contrary, they entangle one another, which makes them subsidiary but also a constituent of each other.

Portrayed in the diamond in Figure 6, this discursive entanglement is where the discourse of standard English becomes powerful, that is, exercises disciplinary power. The discourse in question bounds the construction of high-quality workers for the capitalist society, which is typical of school (Saldarriaga, 2003). Put simply, the discourse of standard English reaches in school, more precisely in an English curriculum, the dissemination of a value-laden view of language (i.e., merely communicative) that is beneficial to international corporations thanks to global and local platforms such as AIESEC and ICETEX, respectively.

This discursive spread takes concrete shape by means of test-oriented teaching, learning, materials, assessment, and other resources that progressively train students in the escalated practice of standard English tests; not to mention the effects of this discourse on the design of statewide exams. On account of what is pinpointed above, for the discourse of standard English to construct candidates for AIESEC-ICETEX calls for applications, it had to implement English curriculum at school as a breeding ground through the exercise of disciplinary power. Consequently, unequal power relationships among orthodoxy and doxa derived into the perpetuation of social orders.

Conclusions

This critical discourse study aimed to shed light on how the discourse of standard English exercised disciplinary power in five scholarships granted by the alliance AIESEC-ICETEX from 2011 to 2014. As a result of a three-tiered analysis (adapted from Fairclough, 2001), the descriptive, interpretive, and explanatory stages findings are synthesized as follows: the discourse of standard English exercised disciplinary power in said scholarships by classifying human beings as competent and not competent users of standard English varieties through examinations, particularly, language tests regarded as valid in the calls for applications. This classification, which was intended to select apt interns and practitioners for AIESEC partners, took a textual shape, namely, a clause complex requesting language proficiency levels through so-called valid tests. Yet, the discourse in question did not exercise power in the vacuum. Rather, it held an intersection with the discourses of globalization, quality in education, and competitiveness and qualifications. In this vein, the applicants to AIESEC-ICETEX scholarships had to fulfill a profile of ideal speakers (competent users of standard English varieties) that were qualified as such as a result of sitting language tests underpinned by measurable indicators (Colella & Díaz-Salazar, 2015), that is, the CEFR. With this in mind, we suggest following up, in further studies, on the role that English language teaching curriculum performs in such construction of language users because it is the field where their subjectivation processes occur mediated by language.