Introduction

In the Colombian teaching context, preservice English language teachers should do their teaching practicum in the last years of their degree according to the study plans designed by the teaching training programs. In some cases, the practicum is mandatory for those students who aspire to obtain their vocational qualifications. According to Nguyen (2014), in this phase, the preservice English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers have a chance to be in contact with a real teaching context, which helps them reinforce, expand, and improve what they learned at university. It means that in this process, preservice EFL teachers have the opportunity to develop the skills to achieve an integral formation as human beings and professionals.

Several studies about the teaching practicum have been conducted. We could find some specific features, such as the preservice EFL teachers’ reflection process, where they are supposed to become critical of their practicum (Insuasty & Zambrano-Castillo, 2010). Another aspect is the “critical incidents” that teachers find and have to face in their preservice teaching process (Farrell, 2008). Also, we identified the worries and responsibilities preservice EFL teachers have at the moment of performing their teaching role, as well as the hopes and feelings of fear, enthusiasm, and even anger that arise while they design and deliver their lessons (Lucero & Roncancio-Castellanos, 2019). Other studies focus on preservice EFL teachers’ voices, showing us that those voices would contribute to curriculum development within institutions (Castañeda-Trujillo & Aguirre-Hernández, 2018). The contributions made by these and other researchers have turned out to be very important to better understand the teaching practicum process and its participants. However, we created a proposal for carrying out a research study analyzing our experiences in our first teaching practicum through a collaborative autoethnography method.

The objective of this study was to interpret and make sense of the challenges that emerged from our expectations and motivations in our first teaching practicum and how we were forced to examine some particularities that emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, we are not leaving behind our initial expectations and motivations, since this research could provide a useful perspective for other preservice EFL teachers who are expected to be in the same situation and who want to know a little about how to make this whole process meaningful and enriching.

Literature Review

Four constructs supported our research, namely: (a) teaching practicum context, (b) preservice teachers’ connection between theory and practicum, (c) the sociocultural approach, and (d) agency development. They are described in the following paragraphs.

Teaching Practicum Context

Teaching practicum has been considered as the process every preservice teacher needs to undergo/engage in in an educational center (primary/high schools, universities, and so on). According to Roland and Beckford (2010), the teaching practicum is the application of pedagogy in a real context: the classroom. In other words, “the teaching practicum then constitutes an opportunity for pre-service teachers to be in contact with real context and to enrich it with social and cultural aspects they might incorporate into their teaching process” (Pinzón-Capador & Guerrero-Nieto, 2018, p. 72).

Some teachers have conducted studies related to the English teacher’s practicum. According to Velasco (2019), the teaching practicum facilitates “a pre-service teacher’s general understanding of the teaching profession and reflects on his/her identity and role as a teacher” (p. 117). This process is viewed more as an “exercise that involves examining the many facets of one’s practice to serve as a guide for a thoughtful assessment” (Velasco, 2019, p. 118). Köksal and Genç (2019) argue that the teaching practicum also “has a fundamental mission as preparing the prospective teachers for the world of teaching since those teacher candidates are mainly expected to be involved in a reciprocal interaction with the learners in the real classrooms during the practicum period” (p. 895). It makes us understand that the teaching practicum is an important aspect of the professional training of preservice teachers since it is here where they have initial contact with a real educational context.

Trent (2010) looks at the teaching practicum “as a crucial aspect of a teacher education program. During the practicum, teacher-interns obtain relevant classroom experience, translate theory to practice, expand their awareness about goal setting and reflect on teaching and learning philosophies” (Gebhard, 2009, as cited in Velasco, 2019, p. 118). Likewise, Okan (2002) claims that “the ability to teach can only be gained through experience. Courses do not prepare you for it. There is too much you have to find out yourself” (p. 176). Many of these scholars agree with the statement that the only way to become an English language teacher is to be in the classroom.

Preservice Teachers’ Connection Between Theory and Practicum

During our professional training, we could notice that teacher education programs are more focused on theory. But, once in the practicum, we evidenced that it goes beyond the theory taught during the course. Sometimes, preservice EFL teachers experience difficulties at the moment of relating theories learned in universities to what happens in their teaching practicum (Meijer et al., 2002). For that reason, the aim of the teaching practicum is to provide preservice EFL teachers the opportunity to be conscious about practicing the theories, methods, and techniques that they acquired in parallel with the process of teacher education (Köksal & Genç, 2019). In other words, the preservice EFL teachers “need multiple opportunities to examine the theoretical knowledge they are exposed to in their professional development opportunities within the familiar context of their learning and teaching experiences” (Johnson & Golombek, 2002, p. 8).

The Sociocultural Approach

We consider that our behaviors, habits, and practices come together and develop from what is ordinary, common, shared, rooted in our close, every day, and familiar surroundings within our culture. In other words, we create personal behavior and lifestyle and adapt them to our surroundings with the other people to take part and get along in society. These patterns (attitudes, values, norms, rules, notions, perceptions, and representations) intervene and determine our way of thinking and acting; therefore, they must be considered as something fundamental when reflecting on how we learn, what we learn, why we learn, and how we teach today.

Johnson (2009) presents some strong arguments where she explains how sociocultural perspectives change the way L2 educators think about teacher learning, language, and language teaching. Furthermore, “learning takes place in a context and evolves through the interaction and participation of the participants in that context” (Richards, 2008, p. 6). Preservice teacher learning is not just about translating knowledge and theories into practice, but also about how the preservice teachers build new knowledge and theories through participation in social contexts. In this sense, the sociocultural perspective is very useful for analyzing and evidencing processes where meaning is generated.

Karimnia (2010) emphasizes that “when language is conceptualized as social practice, the focus of L2 teaching shifts toward helping L2 learners develop the capacity to interpret and generate meanings that are appropriate within the relevant languaculture”1 (p. 222).

Agency Development

Agency is the preservice EFL teacher’s process to move forward, looking to transform and improve his or her professional identity. As Giroux (2004) said, agency “becomes the site through which power is not transcended but reworked, replayed, and restaged in productive ways” (p. 34). This means that preservice EFL teachers should look for the enrichment and improvement of their pedagogical work that may generate action which helps them to consolidate their professional role and performance.

Giroux (2004) also asserts that “the fundamental challenge facing educators within the current age of neoliberalism is to provide the conditions for students to address how knowledge is related to the power of both self-definition and social agency” (pp. 34-35). In short, if teachers develop a sense of agency, this may help them become emancipated from imposed agendas or teaching models and, thus, allow them to construct their own way of teaching and learning.

Method

This research was done under the characteristics of the qualitative approach following a collaborative autoethnography design. According to Castañeda-Trujillo (2020), “this research method permits a collective exploration of researcher subjectivity; it helps to reduce, to a certain extent, the power tensions that can happen while researching in collaboration” (p. 232). In this way, collaborative autoethnography increases and enriches the data and information from an individual interpretation to a collective interpretation. So, this process contributes to building a more in-depth understanding and learning of the self and others. Collaborative autoethnography “consolidates the sense of community since each researcher-participant shares personal accounts that become part of the social construction of the community” (Castañeda-Trujillo, 2020, p. 232). Collecting data through autoethnography allows the researcher to identify and make sense of the various experiences that emerge from the individual to the collective, which are valuable sources of learning. Autoethnography is a relatively personal process because it is based on the personal experiences of researchers. It is, likewise, a highly social process. Autoethnography cautiously looks at how researchers have interacted with different people within their sociocultural context and the way social forces have encouraged their lived experiences.

This study is specific to a concern that emerged in how we, as English language preservice teachers, make sense of our first teaching practicum experiences in our sociocultural context and aim to explore attitudes, perceptions, fears, and challenges surrounding our first teaching practicum.

Context

We were enrolled in an English language teaching BA program at a Colombian public university. The program consists of nine semesters and the last two are usually set aside for the teaching practicum. There is a first practicum (eighth semester) that lasts 16 weeks and where preservice teachers have an initial approach to the classroom experience. The second practicum (ninth semester) serves as consolidation and also lasts 16 weeks. For the purposes of our study, we will focus on the first teaching practicum.

In both practicums, preservice teachers constantly interact with a cooperating teacher and a supervisor, which are a vital component in the pedagogical practicum. The cooperating teacher is a “teacher teaching English at the school identified for practicum [and who] could be requested to assist the university supervisor in observing student teachers teach in classes and offering them comments and further guidance” (Al-Mekhlafi & Naji, 2013, p. 9). For preservice teachers, cooperating teachers are a meaningful and necessary element in the classes. Once we arrive at the classroom, we exchange places with the cooperating teacher since we must be completely immersed in the school context and assume our role as teachers. Even when the cooperating teacher and we exchange our positions, the cooperating teacher does not leave the classroom at any moment. They are always observing us to share recommendations, new teaching strategies, and classroom management techniques. On the other hand, “supervisors are expected to provide their student teachers with a model of instruction, a source of support, feedback and evaluation” (Al-Mekhlafi & Naji, 2013, p. 8). During the teaching practicum, preservice teachers are constantly supervised by the cooperating teacher or the supervisor. Unlike the cooperating teacher, the supervisor regularly observes preservice teachers in their classes and meets with them at least once a week to give feedback on their lesson plans and observations. The supervisor should provide preservice teachers adequate feedback to help them improve their teaching skills. Since the supervisor is an English teacher of the English language teaching program, he or she will also help the preservice teacher improve his or her language proficiency.

For this unique and individual experience, the scenarios were in a public primary school and a private school (1st, 4th, and 5th grades), but also in a public secondary school (10th). In the beginning, we had to go to school six times a week to work with those grades for one or two hours, depending on the schedule of the English classes. As a result of the global outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, we only had three weeks of face-to-face classes. Thus, we had to continue our teaching practicum virtually through synchronous platforms (platforms that simulate traditional face-to-face interaction, and which can be used to provide alternative learning environments for exchange of meaningful information in real time) such as Google Meet and Zoom, or asynchronous (platforms that have to do with the time one can access the information [real-time vs. delayed time]) such as WhatsApp. The period of the practicum was limited to 10 weeks due to the health emergency.

The Participants

We are four participants, three preservice EFL teachers (Elcy, Johana, and Kelly) who met the requirements of the English language teaching program for doing the first teaching practicum, and one student teacher (Lizzeth) in the seventh semester of the same program. Since she was not doing her first teaching practicum, she could not participate in all the data collection processes. For that reason, her role within this research was to analyze and interpret the data collected from reading the journals. The four of us were in our early twenties. Since three of us were about to share a similar experience as it would be our first teaching practicum, we decided to research the challenges, expectations, and insights that we should have in the teaching context to make sense of them from a sociocultural and autoethnography approach. In this study, we played the role of both participants and researchers since our research approach, collaborative autoethnography, allowed us to do so and to engage in self-reflection. As claimed by Castañeda-Trujillo (2020), “collaborative autoethnography is a research process where PELTs [pre-service English-language teachers] will play a role as researchers, to understand their transition from being PELTs to become professional English-language teachers” (p. 221).

Data Collection Tools

To collect the data, we used journals and ethnography observations systematized in written field diaries. According to Richards and Lockhart (2004),

a journal is a teacher’s or a student teacher’s written response to teaching events. Keeping a journal serves two purposes:

(a) events and ideas are recorded for later reflection and

(b) the process of writing itself helps trigger insights about teaching. (p. 7)

For this study, each of us kept a journal wherein we wrote entries at three points, approximately every two weeks (one prior to the practicum, one during the practicum, and one after having finished the practicum) which afterward were then analyzed collectively. Each entry had a prompt (see the Appendix) created by us, in which we wrote individual reflections about our perceptions, feelings, experiences, problems or difficulties, and relationships found within the context of the practicum where we were teaching.

We also used ethnography observation, which consists of three stages (Wolcott, 1994, as cited in Merriam, 2009, p. 201), namely: (a) description (What is going on here?), (b) analysis (the identification of essential features and the systematic description of interrelationships among them), and (c) interpretation (What does it all mean?). The first stage is related to the process of writing journals based on what is happening in our teaching context. The second stage is the process of collecting the journals, and the meetings we will have in each collection to share our experiences through platforms (Google Meet or WhatsApp) to find out common aspects among the data collected. The last stage was developed immediately with the previous one because while we were sharing the information, we also analyzed and highlighted relevant, useful, and common issues that would help us to draw the main findings.

Data Analysis

According to Merriam (2009),

Data analysis is the process of making sense out of the data. And making sense out of data involves consolidating, reducing, and interpreting what people have said and what the researcher has seen and read-it is the process of making meaning. (pp. 175-176)

The approach for this research study is the collaborative autoethnography utilizing a systematic approach to qualitative research methods. “The process involves the simultaneous coding of raw data and the construction of categories that capture relevant characteristics of the document’s content” (Merriam, 2009, p. 205). We focused on the following three stages:

Reviewing data includes “reading text data, analyzing archival materials, graphic information, and physical artifacts” (Chang et al., 2013, p. 102). In this study, we read, reread the journals, and jotted down insights, comments, emerging patterns, and ideas for further work.

Segmenting, categorizing, and regrouping data involves “constructing a preliminary list of topics emerging from the reviewing data and using the topics as the initial codes” (Chang et al., 2013, p. 104). In this stage, we identified some more relevant topics among our experiences and made a preliminary regrouping of data.

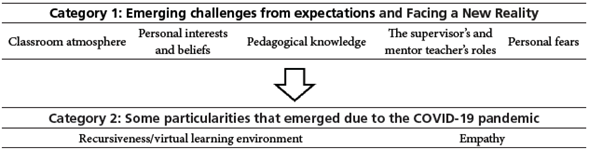

Finding themes and reconnecting with data occurs by identifying the main themes to categorize them and explain how data support and illustrate those themes (Chang et al., 2013). Here, we were able to establish common patterns of two main categories with some subcategories (see Figure 1).

Findings

The reflections were collected, and the appropriate analysis was made to establish common patterns among the participants, in which two categories were identified based on the reflective journals, ethnographic observations, field diaries and conversations obtained. Figure 1 illustrates the main findings of this study.

Category 1: Emerging Challenges From Expectations and Facing a New Reality

This category resulted from our concerns prior to experiencing the teaching practicum. Thus, the excerpts used in the following subcategories are mainly drawn from Entry 1 of our journals where we wanted to get a sense of the expectations we all had regarding what can be considered our first teaching experience.

Classroom Atmosphere

Within this category, we used our individual experiences and knowledge to describe aspects related to our expectations in our first teaching practicum. Having control of the classroom was our main concern before the teaching practicum, which indicates that the preservice teachers’ beliefs in this regard are too narrow. We used to think about classroom management as the process of taking control of the class and over our students, that we would be able to give the class without any interruptions. Some examples of it are Johana’s concern that she would not “be able to take control of the class and, at the same time, catch students’ attention.” Elcy also expressed such worry: “It will be very difficult for me to manage the students.” However, as we mentioned above, this can be seen as a narrow belief if we accept Brophy’s (1996) definition of classroom management as the “actions taken to create and maintain a learning environment conducive to successful instruction” (p. 5). It means that classroom management is not merely to keep control and have rules to maintain order in the schoolroom but also to incorporate the relationship/rapport with the students to create a pleasant environment/atmosphere for the learning process.

Many beliefs about teaching are pre-built from our experiences, or in Johana’s and Elcy’s cases built from others’ perspectives. From a sociocultural standpoint, previous experiences bear great significance in the ways our beliefs evolve and change since we are always immersed in some sort of context, interacting with and participating in it. The aspects of the sociocultural context influence our way of thinking and acting. For instance, drawing from previous experiences and from the opinion of others, Johana and Elcy wrote the following:

I had heard from other preservice teachers that the majority of students from secondary are more difficult to work with. (Johana, Entry 1)

As it has been always known, in the public sector there are many students inside one classroom (35 or more). (Elcy, Entry 1)

As former students in public schools, we have witnessed the difficulties of being a teacher in the public sector where, among others, there is the issue of overcrowded classrooms. Besides, as students in an EFL BA program, we have heard from other preservice and in-service EFL teachers as regards their experiences during their teaching process and some extra information that made us reconsider if our decision of becoming a teacher was appropriate.

During the short time that we had face-to-face classes, we understood that, as teachers, we had to create and develop strategies to catch and maintain the attention and interest of our students in our classes. Here, we recognized that our perceptions about “classroom management” were unfounded and too narrow as to what other preservice teachers told us, that it is not based only on having control and order of the classroom, but it goes further. In Entry 3 of her journal Johana mentioned:

Classroom management is not merely to give students the class rules and that care about their behavior. It should also take into account their individual needs, likes, and ideas, to take advantage of them, to improve and increase their comfort and participation in classes.

Likewise, as teachers, we understood that as part of this context (classroom atmosphere), we enter a constant phase of convincing and negotiating knowledge. We seek to obtain information about our students' experiences and prior knowledge to create bridges of dialogue and understanding as part of the teaching process and starting point in shared learning.

Personal Interests and Beliefs

Other aspects that became visible were the interests focused on the search to transform the self and the other; interests oriented towards mutual strengthening and individual skills to consolidate our personal and professional identities, as evidenced in our journals. In Entry 1 of the journal (before the practicum) Elcy mentioned:

I want to focus on helping to make each student a little better than they are in each one of my classes. I want that the time they will spend in my classes to be time spent becoming better persons or citizens.

Kelly said “I will try to give my best, to research and bring to the classroom meaningful activities for them, where they can develop all their skills almost without realizing it.” Prior to the practicum, we all agreed that we did not only want to transform our students with our work but also to build new skills to help us in our identity-building process, both in the personal and the professional dimensions, as highlighted by Johana: “I will be able to gain knowledge not only about how to teach English to teens and/or to improve my skills.” Zambrano (2002, as cited in Floriano, 2015) affirms that “learning becomes the starting point, and the fundamental concept is the search for such transformation” (para. 2, our translation). Due to our professional training, we realized the need to be a more sensitive and empathetic teacher with students; teachers who care about teaching content and look for ways to influence each of the students positively. In the teaching practicum, we share beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions of identity as individuals impacting the students’ learning through the classroom atmosphere, the types of methodologies, and the strategies we promote in our classes. We believe that teachers are essential in providing students with a meaningful learning environment, an environment where the teacher is not at the center and students passively receive content and knowledge, as was usually the case in our educational experiences (at school and at university). In this measure, we highlight that education involves the act of knowing and not the mere transmission of theory. It is a process characterized by the horizontality of teacher-student relationships where together they learn, seek, and build knowledge. The most important thing is that we see students’ formative stage as a personal transformation process that helps both (students and teachers) build their principles for social projection. In Entry 1 of her journal, Kelly emphasized the impact that the teacher can have on the students’ lives: “I have always thought that primary school teachers have a very important role in children’s learning process. They are the ones who create the solid foundations for the rest of life.” This corresponds to Freire and Horton’s (1990) notion:

The teacher is of course an artist, but being an artist does not mean that he or she can make the profile, can shape the students. What the educator does in teaching is to make it possible for the students to become themselves. (p. 181)

This means that teachers, in their role as guides, supporters, and mediators of knowledge and context, seek to provide their students with the essential foundations so that they assume their role as main actors in the learning process. Thus, through the learning process, students develop and reinvent knowledge, develop self-confidence, self-esteem, and autonomy that allows them to be strong and critical beings in any situation.

Pedagogical Knowledge

How do we know if theory can be put into practice? As preservice EFL teachers, we feel a recurring fear when facing the teaching practicum because we do not feel fully prepared to deal with the reality of putting into practice what we have learned during our professional training. In the university, our professors taught us certain theories, contents, and themes that we must apply once we are in our teaching practicum, but once there, we encountered the individualities of our students, which represented for us not just a source of anxiety and doubts, but also a challenge to overcome. In our journals, we mentioned a concern about the adaptation of the pedagogical knowledge into the context we were going to be immersed in. For instance, in Entry 1 of her journal, Elcy said: “I hope that all that knowledge works for me within the new context in which I am going to be immersed.” Likewise, Johana’s expectation was about putting into practice what she had learned in the university, and Kelly’s concern was “not knowing how to do things.”

It is at this point where we found a gap between what we had learned and the realities of a classroom context. Our professors prepared us as English language teachers mainly through the exposition of the themes in the curriculum and the introduction of techniques and teaching methods. However, the teaching practicum helped us see that educational contexts vary, and that teaching should be adapted to the distinct classroom realities, something which was not explicitly taught in our former courses. So, we are left with the question: How do we link all the theory and content learned during our training to the reality/context of each student?

The Supervisor’s and Cooperating Teacher’s Roles

One of the fundamental components of the pedagogical practicum is the cooperating teacher and the supervisor. We were aware of the importance of these people in our pedagogical practicum. During the data analysis, we agreed that the relationship between the cooperating teacher and the preservice EFL teacher should be one of communication, collaboration, and permanent support.

On the other hand, the supervisor is a big source of knowledge due to his or her teaching experience. The view of the supervisor as an “expert” and the preservice teacher as a “novice” may not be conducive to a fully productive and mutually beneficial relationship. However, we expected supervisors and cooperating teachers to provide us with all their experience in teaching. They would point out aspects such as classroom management or designing and conducting a class and, after every class observation, give us feedback that would enrich and helped us to improve in different aspects. One example of it is Elcy’s expectation:

I expect that my supervisor and my cooperating teacher nurture me with all the experience that they have teaching and to learn from them many techniques and strategies for designing an appropriate lesson plan, conducting the lesson, or how to deal with problems arising in class. (Entry 1)

The expectations are very high concerning the supervisor’s and the cooperating teacher’s roles. In one of the meetings in which important aspects such as challenges and expectations regarding teaching practicum were discussed, we mentioned that we did not want them only to review the lesson plans because, for us, having their support and guidance is vitally important in this new path that will mark our professional training.

Personal Fears

In this subcategory, Johana and Elcy have three personal fears in common. The first was the fear of being judged by the cooperating teacher who observed our lessons. It was a new experience for us to be supervised by another teacher who would evaluate the way we conducted the lessons or revealed our language knowledge. Thus, we became anxious about planning the lessons and about the way we interacted with the students.

The other aspect was related to the knowledge of the language that the cooperating teacher might have. Elcy and Johana placed emphasis on the English level of the cooperating teacher (beginner, intermediate, upper-intermediate, advanced) since, according to them, it would have a great impact on the development of the teaching practicum and their performance as teachers. Johana and Elcy also feared the corrections they could receive from the mentor teacher while they were carrying out the lessons. They thought that the way such corrections are delivered may somehow damage their image in front of their students: These may lose the respect towards the preservice teachers or doubt their abilities. We agreed that such insecurities stemmed from our previous educational experiences, where most of the times, the teacher was seen as an authoritative figure and the depositary of all the knowledge; students, in these conditions, are not expected to make mistakes.

The last fear is related to our students, as, prior to the practicum, there is the uncertainty about their behavior, their learning process, and how the students are going to receive us. Johana stated:

I have to confess that I feel nervous because of the grades I am going to teach and how I will be and how I will create and feed the rapport with my students [or] if I will be able to teach/explain a topic and the students will . . . understand it. (Entry 1)

Elcy also expressed such worry: “It will be difficult for me to manage students because of their ages, their different learning styles, their English level, their behavior.” But, in Kelly’s case, her fear is related to dealing with the different students’ realities. We were willing to put into practice all the theories and concepts we had learned. The concern arose when we faced not only the context of the teaching practicum but also with the different situations that emerged from the individualities of our students. We were immersed in a context where our personalities and realities became invisible from our teaching process since our students were the main actor in classes.

Category 2: Some Particularities That Emerged Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic

This category was developed while we were immersed in the practicum. As such, the reflections that we share here are mainly drawn from Entries 2 and 3 in our journals. We briefly describe the unexpected challenges brought about by the pandemic and how we managed to respond to them.

Recursiveness/Virtual Learning Environment

In Colombia, as in other parts of the world, online lessons have emerged as an alternative to face-to-face lessons due to the restrictions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, education changed dramatically, with the notable rise of online learning, whereby teaching is conducted remotely and on digital platforms. The following question emerged within this new modality: Were we, as preservice EFL teachers and students, really prepared to face this challenge?

To answer bluntly, this unexpected situation caught us unprepared. The technology courses at our university were not enough to help us fill in the learning gaps so that we could effectively impart online lessons, amid all the limitations and inequalities in students’ lives that the situation has made even more evident. According to Sosa-Penayo (2020), “confinement for health issues undoubtedly exposes the large gaps not overcome in the different societies despite the scientific and technological advances of humanity in recent decades” (p. 1, our translation). This global emergency brings out the result of many years of social inequality among Colombian families. A fact that did not go unnoticed by us since in the context in which we were immersed, a significant gap between students from privileged and disadvantaged environments was visible: where the students without the necessary tools or conditions for a quality online education struggled to participate in digital learning. One example of it is Elcy’s experience:

I conducted classes by WhatsApp and I felt helpless and frustrated during my first classes because even though my students were very excited to receive the classes, they could not attend due to lack of resources. (Entry 2)

Apart from that, another concern was that students were not having direct face-to-face contact with their teachers; they did not receive feedback about their lessons during their learning process as they were used to.

Consequently, we used our individual experiences in our first teaching practicum context to describe how recursiveness has become an essential part of the current situation. Due to the new educational context, we had to reinvent ourselves, train and reflect on our work to think of new methodologies, strategies, dynamics, and engage in a reflective analysis on how we would adapt learning and link it with the needs, interests, and particularities of each of our students in such a way that their educational process was not interrupted. These aspects are noticeable in our journals. For instance, Johana mentioned that she had to be more recursive and look for new tools and activities. Moreover, she had to change her way of teaching, to plan new strategies for online classes, and Kelly said that this very particular situation has made her become more recursive and increasingly look for new ideas and tools to implement in her teaching process. For that reason, we started using a variety of different digital tools and programs. But we also designed teaching materials, videos, and guides for those students who could not connect to virtual classes.

Empathy

The changes imposed by the pandemic also made us reflect deeply on the role we had to play in this new context. From the outset, we were aware that it is vital not to leave aside the human dimension of being a teacher and the importance of building rapport with our students. It means that we saw our students as people, and set a relationship based on trust, respect, understanding, listening, and dialogue. We recognized each student as a different being, and not as someone inferior. Within this new context, we strengthened our empathy towards our students and became more aware of their realities and needs. We were worried about those students who could not attend the online classes, so we offered alternatives by designing additional materials for those students. These new experiences made us get out of our comfort zone and brought us enrichment and improvement. We also became more creative and recursive teachers. “Emotions are integral, influential factors in all human beings. They are not only personal dispositions, but also social or cultural constructions, influenced by interpersonal relationships and systems of social values” (Zembylas, 2004, as cited in García-Sánchez et al., 2013, p. 117). In other words, preservice EFL teachers’ attitudes and/or behaviors can vary by keeping in contact with people who are around us: cooperating teachers, supervisors, students, parents, in short, society at large where the role of teachers is under scrutiny.

Conclusions and Implications

This study revealed that we encountered numerous new challenges that emerged from our expectations related to our pedagogical knowledge, interests and personal beliefs, classroom management, aspirations, fears, and vulnerabilities about our first teaching practicum. In addition to this, we strived to find a “professional identity as an ongoing process of interpretation and reinterpretation” (Rasheed, 2017, p. 42) of our relationships built within and out of the teaching contexts.

The teaching practicum was the fundamental space for us to contextualize and implement what we had learned (theory and content) in our teacher training courses. We noticed that those courses failed to take into account the individualities and realities of the students. Although it was a big challenge for us, we were able to handle the situation by recognizing students’ individualities, analyzing their needs, understanding their facilities, and formulating goals and objectives for their learning process.

The process of collaborative autoethnography, in which we shared significant events from the individual to the collective, helped us to understand the teaching practicum and ourselves in a different way, to be more aware of how our experiences become a set of common understandings, to share textual interpretations that give meaning to our experiences, and to create our own perspectives on the context in which the exchange of knowledge took place. But also, to ask ourselves questions and to understand the actions, behaviors, and demands that emerged in our role, in our classes, and in students within the teaching practicum. Hearing and reading the experiences from us was a stimulating, liberating process, and full of new knowledge. We could listen to different points of view and the strategies used by each of us, which were useful for our performance as teachers.

Finally, we were immersed in a virtual learning environment, where we had the opportunity to confront unforeseen changes imposed by the pandemic, familiarize ourselves with possible issues that teachers grapple with, and imagine new ways to be ourselves. We could also provide spaces and generate a creative and innovative impact for learning, and to think of new possibilities of linking the pedagogical curriculum to different contexts where the construction of learning is possible. Besides, it made us reflect, improve our creativity, become more resourceful, and to put ourselves in our students’ shoes by designing the classes and activities in an easy and understandable way while considering the technological problems our students faced.

In this research, some concerns arise about how different personal, experiential, and contextual factors may influence preservice EFL teachers in teaching practicum spaces. Based on the findings, we concluded that, as preservice EFL teachers, we could find ourselves in the process of self-reflection about different pedagogical issues and looking for alternatives to apply them in our teaching practicum. One important implication for the field of education is the need for preservice EFL teachers to be allowed to carry out their own research initiatives regarding the teaching practicum. Their voices may help consolidate the practicum as a space of reflection and learning.