Introduction

In past editorials we have referred to the Profile journal’s national and international ranking achievements (Cárdenas & Nieto-Cruz, 2021; Cárdenas et al., 2020). However, gaining such recognition and being subjected to the logics of evaluation systems convey a risk: silencing some of the voices that have traditionally been welcomed in scientific journals. The Profile journal is not exempt from this potential phenomenon. In fact, since 2020, when the journal was classified for the first time in the Quartile 2 of the Scimago Journal Rank, email queries from interested authors have increased, and so has the number of manuscripts submitted for peer review; and although contributions mainly come from diverse peripherical contexts, the challenge is to ensure the presence of the national and local professional communities that inspired the creation of the publication and that have contributed to its evolution.

The Profile journal remains committed to being an outlet for the opinions and ideas of a diverse community of educators with different educational levels and research experience and who are mainly immersed in social and educational contexts with complex circumstances. In this sense, the journal departs from the scheme followed by “mainstream” journals that usually feature renowned scholars or researchers with long trajectories. Even so, a publication like Profile, edited outside the dominant sphere of the English language teaching profession (i.e., the English-speaking countries), is forced to measure itself against such mainstream, high impact journals due to the current national evaluation system of Colombian scientific periodicals defined by the Ministry of Science and Technology (Minciencias, 2020), which places great emphasis on the position Colombian journals have in international rankings. Thus, there is an imbalance to be addressed between the vision of the journal and institutional requirements.

Our interpretation of what can be regarded as “quality” indicators is not necessarily aligned with the instrumental and effective nature of Colombian economic, scientific, or technological policies. In order to fully grasp the quality of a scientific journal, we need to learn more about the actors involved in its publication; especially from what the theory of symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 2001; Woods, 1983) can tell us about the processes those actors follow while performing a given role within scientific publishing.

With all the previous considerations in mind, we carried out a case study with an ethnographic approach to gather the insights from novice writers and reviewers of the Profile journal regarding the role scientific journals play in community building within knowledge society (Cárdenas, 2021). The study focused on the experiences and beliefs of readers, authors, and reviewers, which has helped me identify elements that could be introduced into an improvement plan closely related to the English language teachers’ local realities. It is hoped that such a plan can contribute to strengthening our communities, our knowledge, and, ultimately, the teaching profession.

In this article, derived from the abovementioned study, the focus is on the authors and the defining characteristics of the types of communities to which they belong. We will also discuss the analytical template followed in the elaboration of an improvement plan for the journal management.

What Can Be Understood by Community?

Basically, a community can be defined by the relationships between its members: proximity (geographical location), commonalities (interests, functions), or any other sort of connection that may emerge and act as a cohesive factor (Cárdenas-Londoño, 2000). Nevertheless, it should be noted that such a definition may imply certain ambiguity because it can be applied to both freedom movements and systems of opression (Bautista, 2012). Thus, when framing a concept of community, we should dispense with a notion of territory as well as with the idealist vision so often found in literature. Krause (2001), for instance, proposes three elements that help distinguish a community from other kinds of human societies: “belonging, subjectively understood as “feeling part of” and “identified with”; interrelationship, that is, communication, interdependence, and mutual influence among the members; and common culture, or the notion of shared meanings” (p. 29; emphasis added, translated from Spanish).

Here, we understand a community as a group of people with shared knowledge, visions, and goals, and who are committed to clearly defined goals, and interact to achieve them. This can be possible even if the members do not inhabit the same geographical area, without face to face contact. A community is not something established beforehand, but it grows thanks to mutual relationships, a disposition to cooperate, the performance of certain roles, and the value given to individual and collective potentiality. The intricacies that arise from the relationships among individuals and collectivities foster the development of educational, learning, academic, professional, and scientific communities. We will next define the last three communities since they have been found to be the main scenarios in which the authors of the Profile journal interact.

Academic Communities

An academic community is usually associated to a university environment. In that regard, it consists of “a significant number of intellectually qualified individuals who undertake research and teaching activities and keep communication channels that allow them to share knowledge and control its value” (Díaz, 1997, pp. 109-110; translated from Spanish). Díaz indicates that, in establishing these communities, five main conditions must be met: (a) a command of the written language for effective scientific communication; (b) a productive mindset that is prepared for the generation of knowledge; (c) the sustained effort of the members to get to know the academic output of national peers and to objectively assess it; (d) an expansion of the sources of reference to include not just books but also specialized journals; and (e) the capability of accessing knowledge in other languages. Regarding the first condition, Romero-Serna (2000) sees writing as the communicative tool that facilitates the rearrangement of the paradigms shared by a community. For this author, interaction through writing helps “modify and generate theory, validate existing knowledge, accept or reject theoretical arguments, and foster the preservation or transformation of dogma for future generations” (p. 21; translated from Spanish).

An academic community is a particular way of academic organization that groups certain kind of individuals (students, educators, administrators, supervisors, and directors) for whom education is the main activity (Cárdenas-Londoño, 2000). Its members have a particular view of the world and an approach to certain theories that is submitted to constant scrutiny (Romero-Serna, 2000). Furthermore, as found by Francis-Salazar and Marín-Sánchez (2010) in a study on the role of academic communities in the construction of university teachers’ pedagogical knowledge, there are subcommunities within communities as a direct result of the environments inhabited by faculty members when performing their work, which is to say, based on professional, disciplinary, or work-related issues. Thus, there are groups formed around, for example, the teachers’ contract type or their relationship with the institution.

Professional Communities

These types of associations seek group cohesion based on professions. Such disciplinary boundary, present in academic communities as well, allows professional communities to set themselves apart from others and to gather their members around three substantial elements: (a) institutions, (b) disciplines, and (c) recognition and prestige (Francis-Salazar & Marín-Sánchez, 2010). Such elements can be found in a community like TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages), conceived by Canagarajah (2016) as a professional community focused on pedagogy, research, and theory, and with an evolution from modern to postmodern orientations in its disciplinary discourse. This is clear in the way knowledge is made available through the TESOL Quarterly journal, which brings together authors from diverse geographical areas and features articles that report on a variety of studies with different research methods. We concur with Canagarajah in that, while this diversity can be perceived as a threat to the overall cohession of TESOL, it may contribute to expanding the range of the community’s knowledge base, thus fostering its growth.

From this perspective, we suggest that teachers at primary and secondary levels can improve their professional practice as well as understand the specific details of research when they belong to professional communities; which, in our case, are teaching communities (Cárdenas, 2002). These communities can emerge within the framework of professional development programs (precisely the kind in which the Profile journal was conceived), which may require redefining the way the latter are designed and developed. In the communities thus established, teachers with different academic backgrounds and educational contexts can converge around common interests. Wells (1999) calls this notion of collaborative collective work a “community of inquiry” or research community and differentiates it from a community of practice in that it broadens the point of view to focus not just on learning but also on knowledge building. For Cochran-Smith and Lytle (1993, 1999), these are teacher-led research communities which have an impact on educational reforms. Finally, we would like to underscore that the interactive work between teachers in basic education and teacher educators was the point of departure for the Profile journal, which may help explain the role of scientific publications in the creation of communities within the knowledge society (Cárdenas, 2021).

Scientific Community

For Kuhn (1975), a scientific community is made up of professionals of a scientific discipline joined by common elements: permanent communication, unanimity in judging professional issues, and education. Kuhn goes on to describe the composition of a scientific community through two types of factors: (a) values and norms and (b) theoretical and methodological elements. The former shape the relations among scientists, the way they work and organize themselves, their institutional enclave, and the nature of their leadership. As for the theoretical and methodological elements, these involve shared commitments of scrutiny derived from scientific activity.

For Kreimer (1998), scientific communities gather representatives who, in general, exercise great control over most institutions involved in research, including their funding. The development and consolidation of scientific fields are usually a consequence of dynamic interactions that take place within specific contexts. Kreimer notes that many of those representatives tend to adopt conservative attitudes towards the emergence of new subject interests, research profiles, and disciplinary assignments.

From our object of research, we distance ourselves from such concepts. While publishing in a scientific journal is a challenge and may provide access to a scientific community, it does not mean that one is part of an elite. To become part, as an author, of the community of a periodical journal coincides with the interest of that journal in sharing quality scientific knowledge. Being a member of such a community implies an open attitude to be able to make contributions and accept the outcomes of making our work public. In fact, under current circumstances, indicators such as the number of studies and published articles, conference attendance and proceedings, the communication and relations with communities in the same or related fields, to name a few, are used to frame scientific communities within national and international contexts and to give faith of their existence. Scientific journals help comply with most of these indicators, and their underlying plurality in scope functions as a way to regulate the relationships that arise “within scientific communities and among them and other social systems” (Capurro, 2015, p. 17). Nonetheless, the sense of cloister and exclusion that seems to surrond scientific communities indicates that relations of power are part of the scientific ethos, which can be evident, for instance, among research groups and their impact on training researchers; in search of products that can help rate and classify scholars and their research groups; and, as indicated before, in national policies based on journal ranking systems administered by highly commercial companies.

Some of these inconveniences have been surpassed in time while others prevail and influence, with varying degrees, the classification of Colombian scientific communities as “emergent” or “under development.” Furthermore, despite the perception of superiority that society usually has towards academic and scientific communities, as elites in the production and advancement of knowledge, significant efforts are needed to strengthen them for “neither market forces nor other kinds of spontaneous social forces are enough, on their own, to foster the development of structures for the production and dissemination of a nation’s scientific and technological knowledge” (Forero-Pineda, 2000, p. 9; translated from Spanish). This becomes even more necessary in communities like the one where the Profile journal is edited, as well as in those to which the authors and readers of the journal belong.

Improvement Plan for the Generation of Communities Around the Profile Journal

To move forward with the creation of communities, we should bear in mind the external circumstances that can impact the achievement of said goal. Although we, as editors, may not have direct control over such circumstances, it is possible to assess the editorial and publication practices of the journal as well as the actions aimed at contributing to the communities where the authors-and, ideally, the readers-may have some influence. Therefore, we have designed an improvement plan aimed at strengthening editorial management and, thus, advance our contributions to generating and consolidating communities. Based on the protocol proposed by the National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation (Agencia Nacional de Evaluación de la Calidad y Acreditación, ANECA, n.d.)1, the plan includes five elements:

Identifying areas of improvement

Detecting the main causes of the problem

Defining goals for each area of improvement

Selecting actions for improvement

Scheduling a follow-up plan

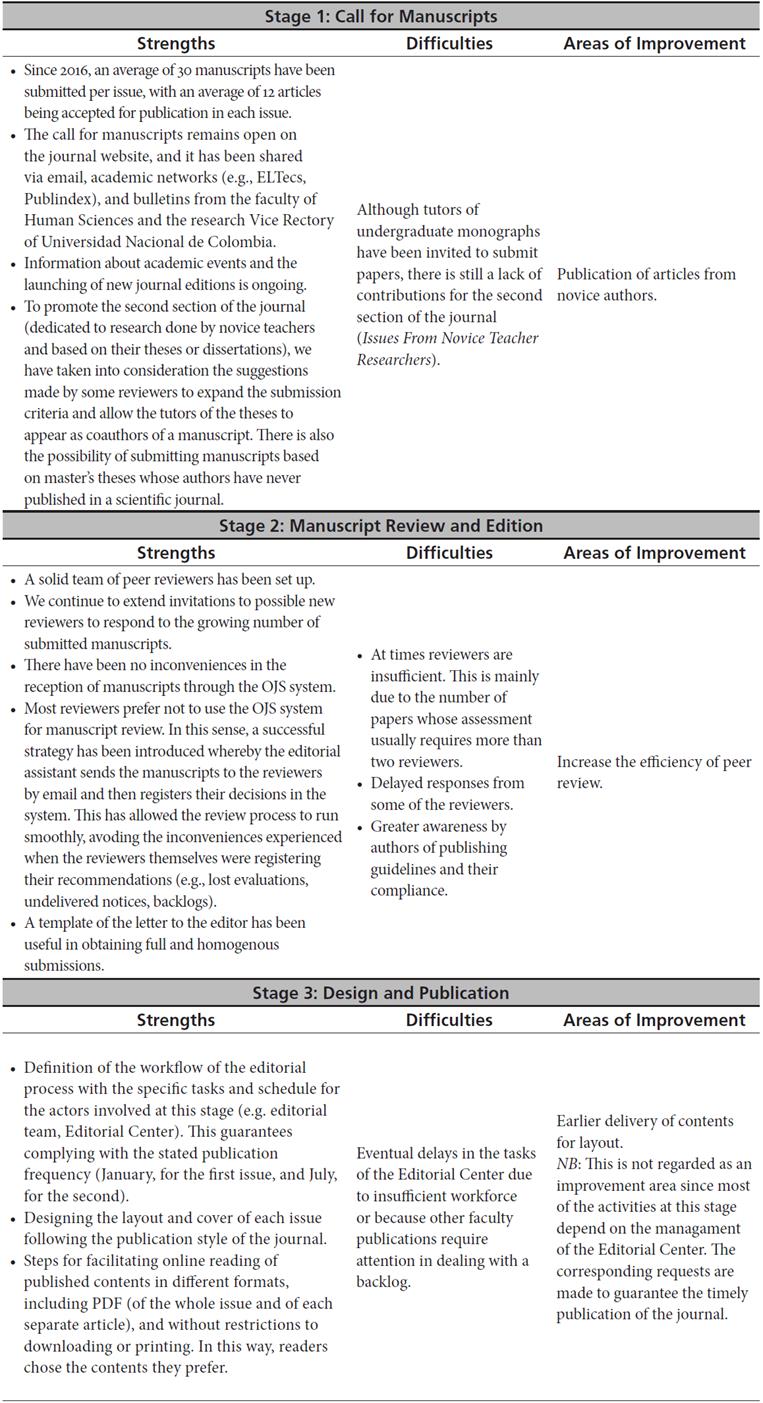

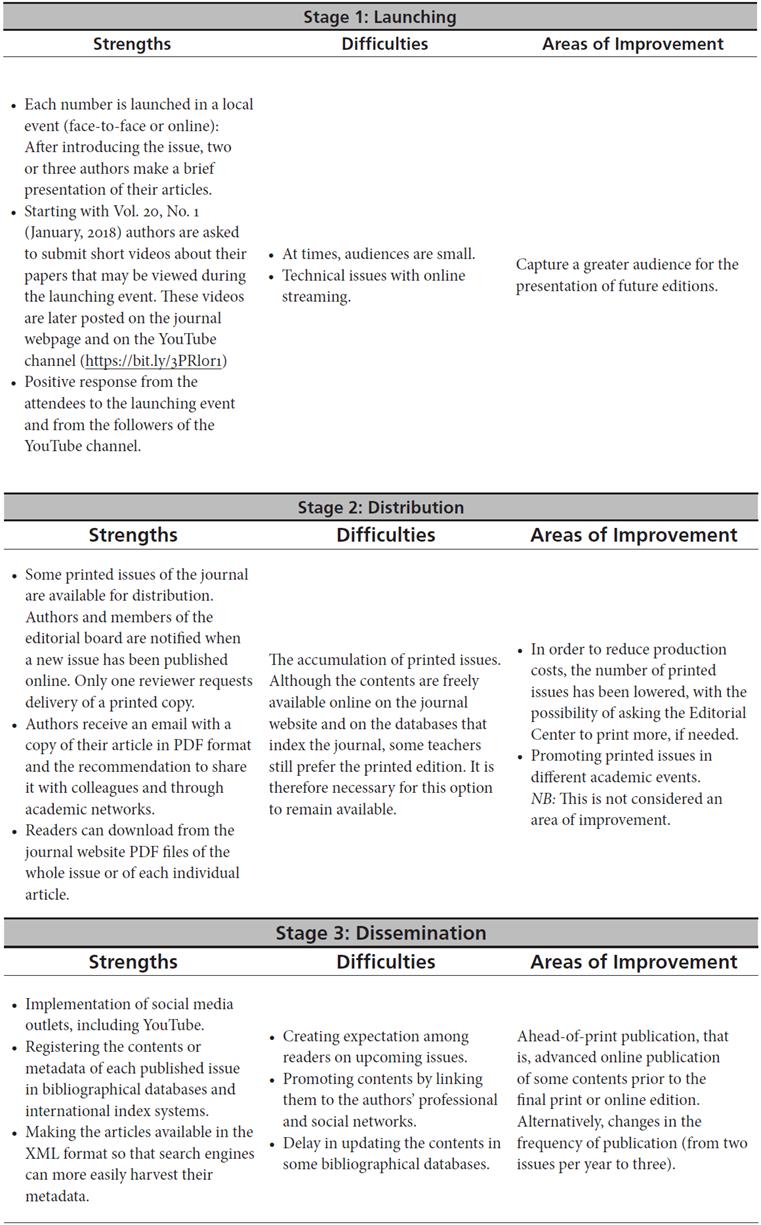

The workflow of the editorial process to produce a journal issue generally comprises two great areas: editorial management and visibility. The first includes (a) a call for manuscripts, (b) manuscript review and edition, and (c) design and publication. As for visibility, three post-publication stages are taken into account: (a) launching, (b) distribution, and (c) dissemination.

In drafting the improvement plan, we resorted to the following input: (a) analysis of the editorial process and emails related to it from 2014 to the second semester of 2020 (this was carried out by the editor with the help of the editorial assistant); (b) records of institutional and national guidelines and initiatives that favored the visibility of Colombian journals; (c) interactions with authos, reviewers, and other actors involved in the production of the journal (e.g., the Editorial Center of the faculty, the University’s library division, the indexing and referencing systems); and (d) the suggestions, collected via interviews and emails, made by the participants of the study on which this paper is based.

Identifying Areas of Improvement

The starting point in detecting areas of improvement includes the set of strengths and difficulties drawn from the sources indicated above. Since the editing stages are interrelated, and the strengths and difficulties were at times duplicated, these were grouped into the two great areas that make up the editorial workflow: editorial management and visibility (see Tables 1 & 2).

Action Plan for Improvement

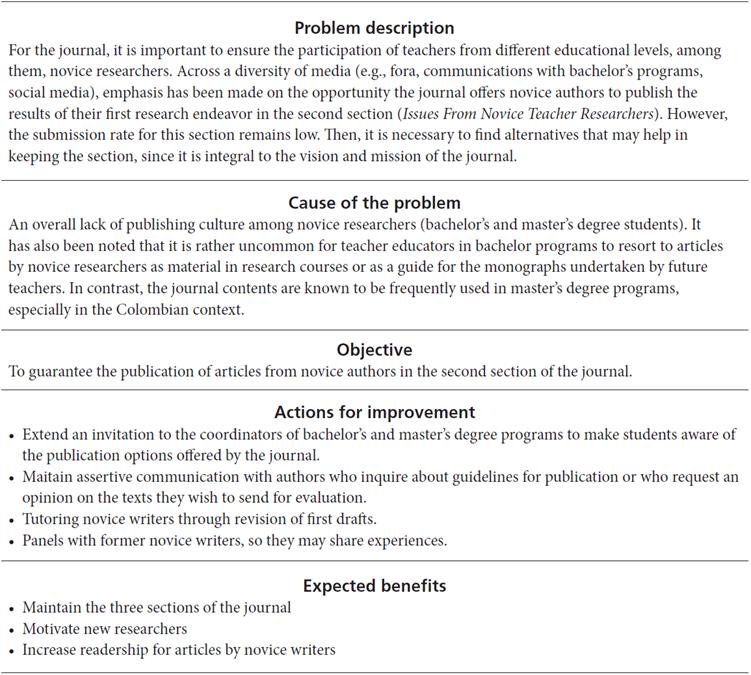

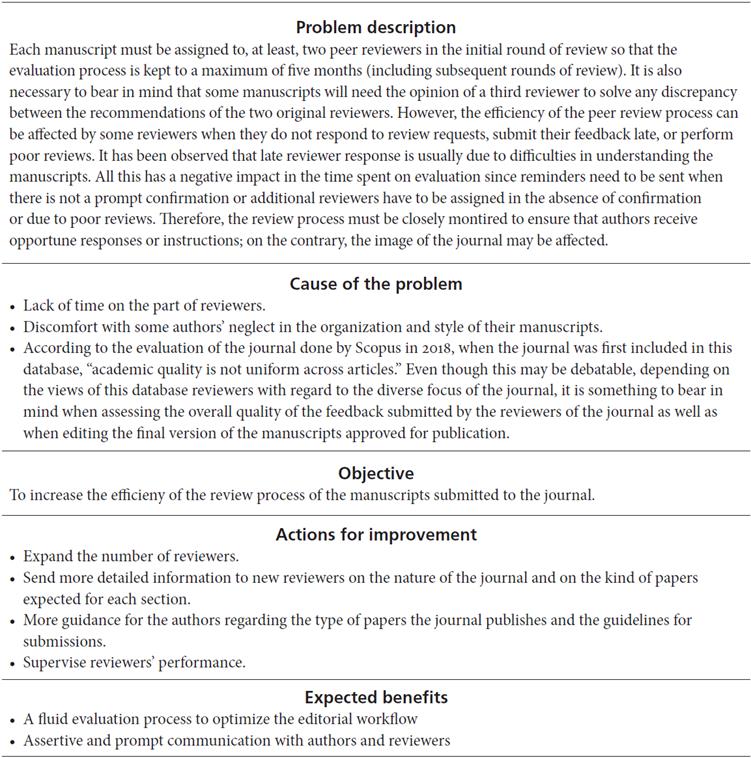

Once the four areas of improvement have been identified (publication of articles from novice authors, increasing the efficiency of peer review, capturing a greater audience for the presentation of future editions, and ahead-of-print publication or change in publication frequency), we establish the cause of the problem. Next, we define goals of improvement, the actions to be taken within certain time limits, and the expected benefits. Finally, we specify the follow-up tasks for each area with regard to the planned improvement actions. In our case, roles and responsibilities are not included since the editor and the assistant editor are in charge of all the improvement plan. In the following sections, we detail the action plan for each of the areas under scrutiny: editorial management and visibility.

Action Plan for Editorial Management

We found two areas that require attention to optimize editorial management. The first has to do with keeping one of the distinctive traits of the journal: the publication of articles from novice authors (teachers at the end of their undergraduate or master’s studies; see Table 3). The second area refers to increasing the efficiency of peer review (see Table 4).2

Action Plan for Visibility

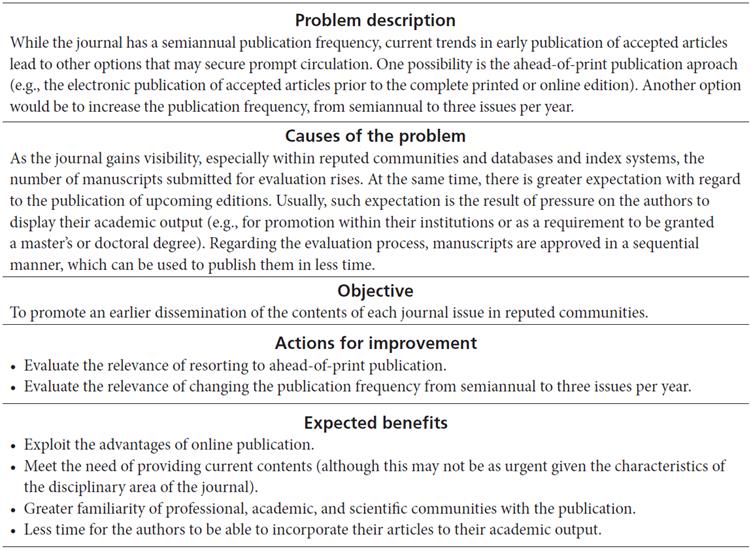

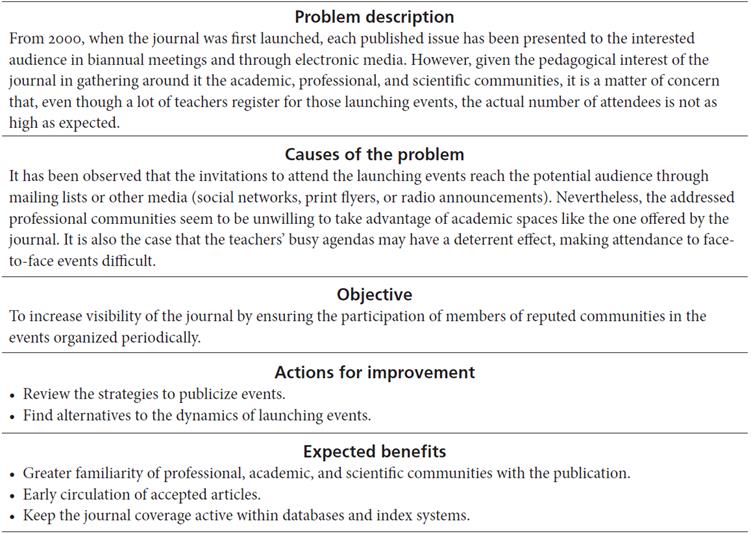

Even though the Profile journal has made progress in terms of visibility, we acknowledge the need for improvement in two areas: a larger audience for the launching events and earlier publication of articles. With regard to this last issue, and as detailed below, the expectations of readers and the trends in scientific publication should be analyzed to help decide whether to opt for the ahead-of-print dynamics or change the publication frequency of the journal. Tables 5 and 6 show the details of the plan for improvement in the mentioned areas.

Table 5 Improvement Area No. 3: Capturing a Greater Audience for the Presentation of Future Editions of the Journal

Concluding Remarks

We can see that the elements included in the improvement plan demand great efforts to respond to the needs of national and international communities. Publishing in peer reviewed journals allows members of a community to establish academic contact, to keep abreast of the latest development in their area of expertise, to evaluate the quality and relevance of the work they perform, and, ultimately, to establish collaborative relationships with peers. Therefore, the job done by the editorial staff of scientific journals, as venues where communities emerge and grow, is of paramount importance, and special attention should be paid to permanently monitor specific editorial processes to identify areas of improvement and implement the necessary actions.

The improvement plan described in this paper gathers some core issues that may allow us to move forward with the sustained publication of the journal, according to current editorial practices and the results of the study done with novice writers and reviewers (Cárdenas, 2021). We can see that the areas of improvement are not just the result of the need to respond to the external metrics of journal evaluation systems. Such areas are already an integral part of good practices in academic publications. Above all, our interest is to foresee actions aligned with the journal’s socio-critical vision, which is fundamental in guiding the mission of the journal as a forum that facilitates the incorporation of English language teachers’ academic writing into professional, academic, and scientific communities; thus, contribute to the field of English language teaching and learning. In that regard, “our aim of enriching the professional knowledge of our authors and readers and thus, create and strengthen an international academic community around the teaching and learning of English as a foreign/second language,” remains constant (Cárdenas et al., 2020, pp. 9-10).

The demanding editorial management of a journal includes complex processes that usually revolve around universal or particular publication norms. Overwhelmed by the dynamics of the manuscript evaluation process, we usually forget that communication with authors and reviewers may offer a glimpse into circumstances worthy of study. In our case, interpreting the voices and experiences of the participants allowed us to have a closer look at the reconstruction of meanings derived from their beliefs and to unveil the personal and professional circumstances attributable to publishing in a scientific journal; circumstances that are somehow connected to the scientific and professional communities in the writers’ local or international contexts. We expect that the actions included in the improvement plan may also be a reference for studies on academic writing, the editorial processes of academic journals, and alternatives in supporting educators from different educational levels and geographical contexts interested in divulging their work through journal publishing.