Introduction

Historically speaking, language teacher identity (LTI) has been associated with the overall set of practices, beliefs, and behaviors that characterize educators immersed within the language teaching field. Nevertheless, the recent insertion of other theoretical perspectives into LTI theory, particularly those drawing from psychology, sociolinguistics, and even philosophy, has made the theorization of LTI more complex (Varghese et al., 2005). For Norton (2017), LTI “indexes both social structure and human agency, which shift over historical time and social context” (p. 81), whereas to Barkhuizen (2016) and Beauchamp and Thomas (2009), LTI is related to the gradual and constant negotiation of language teachers’ identity markers inside and outside the classroom contexts (Gee, 2000; Kumaravadivelu, 2012). That is to say that the sociocultural and contextual experiences they go through in their lives as teachers help them reflect upon who they want to become (van Lankveld et al., 2016).

In Colombia, academics such as Macías-Villegas et al. (2020) have held that LTI is a process of construction that occurs within academic and non-academic contexts. When LTI takes place within the first setting, language teacher education programs as well as continuous professional development programs gain relevance (Freeman, 1989). This is reasonable bearing in mind that language teacher education programs represent the place where preservice teachers are first exposed to their teaching experiences. Alternatively, LTI construction can also take place within the framework of the second scenario, where social interactions and community involvement play a fundamental role.

Bearing that in mind, this research study seeks to contribute to the body of scholarly literature revolving around the field of LTI in Colombia by reporting how a master’s program with an emphasis on English language teaching (ELT) influenced the identity trajectories of a group of four English language teachers. In doing so, we set the following research objectives: (a) to explore four English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers’ identities trajectories before and after their participation in a master’s program in ELT and (b) to describe the role of the master’s program in ELT in the shaping or reshaping process regarding EFL teachers’ professional identities.

Literature Review

Developing a Language Teacher Identity

Scholars from varied settings have long suggested that LTI develops based on individuals’ constant academic experiences during their time as preservice teachers within the framework of language teacher education programs (Freeman, 1989; Trent, 2010). In the international scenario, Crandall (2000) has manifested that LTI constitutes the space where preservice teachers’ contact with learning and teaching methodologies shape not only their initial professional development dimension and their initial teaching repertoire as language instructors, but also their initial LTI. This makes sense considering that teacher education programs represent the place where preservice teachers are exposed to their initial teaching experiences. In Colombia, authors such as Macías-Villegas et al. (2020) have held that pedagogical, methodological, sociocultural, and community-based experiences contribute to the development of initial language teachers’ identities, beliefs, and teaching practices (Freeman, 1989; Trent, 2010). These aspects are reaffirmed by Hernández-Varona and Gutiérrez-Álvarez (2020) who found that, when engaged in community- and social-based projects, preservice language teachers were able to develop other dimensions of their teaching selves.

Crandall (2000) also suggests that teachers’ previous experiences become essential to understand how these might contribute to shaping their views towards learning and teaching processes and their overall identity. Borg (2004) and Freeman (1989) have also supported the idea that teachers’ early learning experiences do not only allow them to envisage their practices as future novice teachers, but also to recognize the kind of individual they would like to become, suggesting that LTI is not a linear process that necessarily develops based on college- and academic-related experiences. It also emerges from non-linear experiences embedded in the social, cultural, contextual, and personal dimensions. In view of this, LTI involves analyzing “how a person understands his/her relationship to the world, and how that relationship is constructed across time and space” (Norton, 2013, p. 45).

In the international spectrum, LTI has been widely examined under several lenses. While some scholars have used Bakhtinian and Vygotskyan frameworks, others have followed principles of critical positioning theory and communities of practice (Kayi-Aydar, 2019) to understand how language educators integrate their experiences into the classroom setting. Abednia (2012) established that LTI develops from continuous participation in professionalization programs. He found that, after constant exposure to critical EFL theories, the participants (seven Iranian English teachers) were able to gradually move from their roles as “passive technicians” (Kumaravadivelu, 2003) to what Kumaravadivelu (2003) regards as “reflective practitioners” and “transformative intellectuals.” This occurred because of the exposure to critical theories and the opportunities the participants shared to detach from hegemonic/neoliberal perspectives.

Similar findings were reported by Brutt-Griffler and Samimy (1999), who analyzed the self-representation of a group of non-native English-speaking teachers (NNESTs) and established that these usually subordinated themselves to their counterpart, the native speakers. Yet, through the constant integration of critical theory into the classes these teachers were enrolled in, they found that deficit discourses (Hayes et al., 2017) about nativeness were dismantled and abandoned. Thus, participants were able to develop a collective consciousness regarding their condition as NNESTs as well as their own transformed professional voices.

Other studies have centered on areas such as the negotiation of language teachers’ sociocultural identities and their context (Ajayi, 2010; Duff & Uchida, 1997), the relationship between the working life and construction of professional identities of EFL/ESL teachers through life history narratives (Johnston, 1997; Simon-Maeda, 2004), the intersection between race and LTI (Amin, 1997; Golombek & Jordan, 2005; Motha, 2006), and the combination of LTI and narrative inquiry (Liu & Xu, 2011; Tsui, 2007). These studies have made important contributions to the LTI field and have demonstrated that it is an area of interest that has been growing within the last few years.

In Colombia, scholars’ interest in LTI has also gained increasing attention. To ratify this, we carried out a categorization exercise within the framework of five ELT specialized journals and two specialized databases. We specifically searched for articles revolving around the themes of “identity,” “language teacher identity,” and “language teacher identity in Colombia.” This task led us to conclude that research studies in Colombia have explored LTI in diverse scenarios, that is, the intersection between LTI and undergraduate education (Hernández-Varona & Gutiérrez-Álvarez, 2020; Macías-Villegas et al., 2020); queer LTI (Lander, 2018; Ubaque-Casallas & Castañeda-Peña, 2021); LTI negotiation within the context of deterritorialized spaces (Guerrero & Meadows, 2015); the identity of indigenous English language teachers (Arias-Cepeda, 2020); and the intersection between LTI and autoethnography (Castañeda-Trujillo, 2020). These studies contribute to a wider understanding of how LTI has been integrated into the field of language education in the Colombian context.

The literature review allowed us to determine that, although undergraduate education has been a recurrent scenario for exploring and understanding LTI construction processes, more recently, the area of professional development as well as components inherent to it have been gaining increasing interest. Therefore, this study may reduce the existing gap on teacher’s identity shaping in the context of professional development programs; and more specifically, within the framework of postgraduate education with an emphasis on ELT.

Method

In this study, firstly, we followed the principles of qualitative narrative research, which allowed us to explore, analyze, and understand experiences embedded within the socio-educational dimension (Flick, 2009; Saldaña, 2011; Stake, 2010). Secondly, we applied principles of narrative inquiry because eliciting individuals’ stories constitutes an excellent source of knowing and making meaning of their experiences (Dwyer & Emerald, 2017), and provides the chance to understand them from within (Bell, 2014; Kramp, 2004). In this regard, authors such as Barkhuizen (2016) and Merriam (2009) contend that narratives constitute an essential element for understanding identity.

Participants and Context of the Study

We chose the participants of our study using a judgment sampling technique. The judgement or purposeful sampling technique consists of selecting the “most productive sample to answer the guiding research question” (Marshall, 1996, p. 523), which implied recruiting participants (in this case, English language teachers) who had attended and successfully graduated from a master’s program in ELT from a local university in southern Colombia. Bearing these considerations in mind, we initially invited, via email, 30 English teachers to participate: four of them accepted. To protect their real identities, we assigned some pseudonyms. “Julio” was the name given to the only man of the group, while “Daniela,” “Angela,” and “Fernanda” were assigned to the three female participants. Below we provide a richer description of the participants’ profiles.

Julio is a 28-year-old teacher who currently works in a rural school in Garzón, Huila.1 He pursued his bachelor’s degree and master’s degree in ELT in the region of Huila. Julio has been an English teacher for eight years and his research interests lie in rural education and material development; this, because of his proximity to this context.

Daniela is 29 years old and works in a public school in Teruel, Huila. She completed her undergraduate studies in 2013 and, by 2014, she decided to continue her studies in the master’s degree in ELT. She graduated from the program in 2017. She has six years of teaching experience in the private and public sector and her interests are the development of communicative skills and didactics.

Angela is a 30-year-old teacher who pursued her bachelor’s and master’s degree in English education in Huila. Angela is a full time English teacher at a public school in Garzón, Huila, and her research interests revolve around professional development, teacher identity, and primary teacher practices in relation with ELT.

Fernanda is a 28-year-old EFL teacher who finished her bachelor’s degree in 2015 and her master’s degree in 2017. She has been an English teacher for eight years and her main research interests deal with the incorporation of multimodal tasks into EFL processes.

Characteristics of the Master’s Program in ELT

This specific master’s program in ELT is a postgraduate educational level offered by a public university located in Huila. Typical candidates who enroll in the program are English language teachers. Yet, individuals whose educational backgrounds are different can be accepted if they meet a very specific requirement: having at least a demonstrable B2 level of English proficiency (according to the Common European Framework of Reference). In general, the master’s lasts four semesters and its overall curriculum contents cover specific subjects within the fields of second language acquisition and English language teaching and research.

Researchers’ Positionality

By the time we conducted the study, we were two EFL teachers with different roles: one of us was an active EFL public rural school teacher and a IV semester student of the master’s program we referred to previously, while the other was an EFL teacher educator with an MA in ELT. Since we had been involved in the same academic experience, we intended to minimize possible biases by checking for alternative viewpoints regarding the study. In doing so, we consulted a colleague who specializes in qualitative research and, based on the discussion revolving around LTI and narrative inquiry we had with him, we refined some sections of the study to increase its degree of trustworthiness.

Even though we did not know the participants personally, our own participation as former MA students in ELT seems to have been one of the vital elements for triggering their interest in enrolling in this research, as they acknowledged being concerned about their teaching selves (Danielewicz, 2014) before and after such academic experiences. Overall, their acceptance was beneficial because they showed a very high level of commitment and openness towards the research. We believe, though, that having a larger sample of participants in future studies would be favorable to keep shedding light on other aspects regarding LTI, including LTI construction either as researchers or as language teacher educators.

Data Collection Instruments and Analysis

Two data collection instruments were used for this study: oral narratives and narrative interviews. Overall, narratives elicit stories in order to explore one or several moments in the participants’ lives (Barkhuizen, 2016) and can be collected in different formats (written or oral). Understanding this, and given the participants’ availability, we decided firstly to gather their narratives orally. Secondly, we implemented narrative interviews because of the opportunities they provide to “[reconstruct] social events from the point of view of informants” (Muylaert et al., 2014, p. 185). According to Kartch (2017), “in a narrative interview, the researcher is not looking for answers to questions; rather, he or she is looking for the participant’s story” (p. 1073). Consequently, both oral narratives and narrative interviews were conducted interchangeably to complement the information gathered from each instrument and thus increase the grade of detail in each participant’s story.

In this order of ideas, we collected oral narratives and performed interviews at three instances: first, we explored participants’ initial contact with English during their childhood, their school time as primary and secondary students, and their (if there were) English learning experiences in language institutes. Second, we examined participants’ experiences as preservice English language teachers in the undergraduate program, their experiences abroad, and their first formal jobs as language teachers. Finally, we delved into participants’ experiences as candidates and then as students in the master’s in ELT.

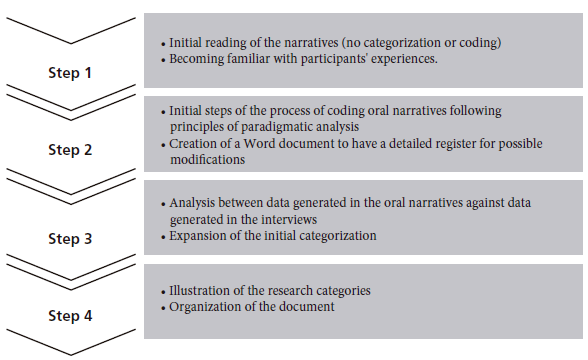

The data collection process took place in the last semester of 2019 and the first trimester of 2020. For data analysis we followed the principles of the paradigmatic approach. This approach recommends the proposition of categories (Polkinghorne, 1995, p. 14) and encourages the identification of particular occurrences within the data to relate them with the established categories to make sense of the stories. Consequently, we followed a four-step analysis: Step 1 consisted of becoming familiar with participants’ experiences; Step 2 was related to the initial process of coding the narratives in the software Atlas.TI; Step 3 centered on expanding the initial categorization and analyzing data stemming from the oral narratives along with the narrative interviews; and Step 4 focused on illustrating the research categories emerging from the overall process of data analysis (see Figure 1).

Findings

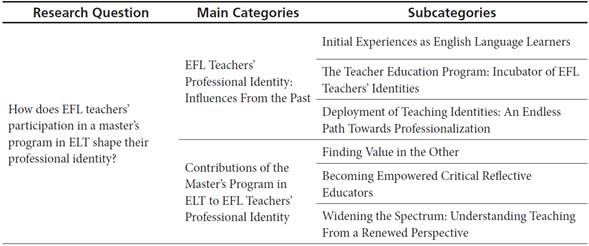

In this section, we present the results obtained from the analysis of the collected data aimed at exploring four EFL teachers’ identities trajectories prior to and after their participation in a master’s program. Two main categories emerged (see Table 1) which were paramount in understanding that identity construction is a dynamic process continuously developing from the experiences lived by the educator (even before becoming one) and is not limited to a particular event. Additionally, the categories show that postgraduate education promotes opportunities for further identity development, enabling teachers to reflect upon and think critically about their role in education.

EFL Teacher Professional Identity: Influences From the Past

LTI construction is regarded by some professionals as a process that begins when individuals formally enroll in language teacher education programs and begin to receive methodological and pedagogical influences to become teachers. This first category elicits the process participants went through since the very first contact they had with ELT methodologies from their positions as primary and secondary students. It also unveils their initial educator’s identity construction in their undergraduate program.

Initial Experiences as English Language Learners

This subcategory shows that participants’ previous learning experiences in primary and secondary education played a determining role in the reflection made around their initial practices as language teachers. Positioning themselves in their former role as pupils, participants intrinsically identified common teaching characteristics and behaviors enacted by their school teachers and made connections with their subsequent decision to become teachers.

I had two spectacular teachers; one [of them] was a very special person and educator. I loved her classes. The other teacher’s classes were spectacular. I think that is one of the reasons why I like English. (Daniela, Narrative Interview 1)2

My mother is a primary school teacher. She has worked in rural zones. My cousin also studied English in the teacher education program. I have another cousin who studied child pedagogy. I was raised in an environment of teachers . . . I consider that growing in such environments makes you feel attracted to the profession. The context in which one grows is important. (Julio, Narrative Interview 1)

In the previous excerpts, the two participants reflect upon their experiences as English language learners during primary and secondary school where they acknowledge having been influenced directly or indirectly by their former EFL teachers. About this aspect, Borg (2004) highlights that “the apprenticeship of observation describes the phenomenon whereby student teachers arrive for their training courses having spent thousands of hours as school children observing and evaluating professionals in action” (p. 274). Likewise, Freeman and Richards (1996) stress that novice teachers replicate classroom practices gained from apprenticeship of observation, which leads us to suggest that previous experiences with educators and the teaching context (in general) constitute a fundamental element in the construction of a prospective EFL teacher’s identity. Considering this, EFL teacher’s identity embraces a multifaceted process which begins to be shaped from students’ passive roles as language learners and which is equally influenced later by other social, educational, and cultural settings related to formal ELT processes.

The Teacher Education Program: Incubator of EFL Teachers’ Identities

This subcategory exemplifies the identity consolidation of EFL teachers resulting from their enrollment in a language teacher education program. Codes such as “initial experiences in the undergraduate program,” “experiences with classmates and professors,” and “ELT in situ” strengthen the notion of preservice education programs as seedbeds for their initial teacher professional identity construction.

At the beginning, I did not see myself as a teacher. I saw myself only as someone who was learning EFL. (Julio, Oral Narrative 1)

At first, I was not fully aware of my future as a teacher. (Daniela, Oral Narrative 1)

Having [name-of-teacher] as my first professor in the teacher education program motivated me because I saw in her a successful woman, who was teaching English at a university. I wanted to be like her. I think that the professor’s image was beneficial to my formation and made me feel more secure about my decision about the program. (Angela, Narrative Interview 1)

Although participants did not see themselves initially as teachers, most experiences they had as university students did change this perspective, and cemented their own teaching images, which means that undergraduate programs represent adequate scenarios for preservice teacher identities to emerge because of their academic, social, and pedagogical dimensions (Pianta et al., 2012; Vermunt, 2014). Although the academic and social dimensions play a determining factor in the initial consolidation of teachers’ identity, in-situ teaching experiences and exchange encounters also triggered these formation processes, as seen in the following excerpt:

We had to make class observations for the university. All of them were oriented by the teachers. There was an objective behind each observation. Also, we had to reflect upon what we had seen. After this, we analyzed the methodology employed by the teacher, the thematic unit, and the objectives of the class. Then, you had to create a class, I mean some short classes for a period of time before the teaching practicum. . . . Now that I recall having been in [the US], having listened to varied accents, and having learned different vocabulary, I consider it fundamental for the development of language educators. I was not the same before and after that trip. (Julio, Narrative Interview 1)

As evidenced previously, Julio suggests that his first approximations to language teaching allowed him to put into practice certain methodological procedures, which gave him the opportunity to reflect and work on what he had studied. Following Wenger’s (1999) view, identity formation “begins when it takes place in the doing” (p. 3), which indicates that in-situ experiences provide student teachers with valuable approximations to the teaching field, thus forging views on methodologies and approaches as well as the decision-making behind a class. Additionally, Julio suggests that his identity changed after a trip to the US. In this regard, authors such as Medina et al. (2015) and Martinsen (2011) have noted that multicultural and traveling abroad experiences are essential for student teachers’ preparation because these foster a more positive attitude toward language learning and teaching.

Deployment of Teaching Identities: An Endless Path Towards Professionalization

We found that participants faced other circumstances after finishing the undergraduate program. Being in shock with reality and implementing context-sensitive teaching practices were some of the most reported situations.

The first formal job I had as an EFL teacher was at a private institution. It was a very small private school located in the city of Neiva. I had to teach third, fourth, and fifth graders. In fifth grade there were 15 students. In fourth grade there were nine students. Student population was small. I remember that the kids learned very fast. (Julio, Narrative Interview 2)

When I began to teach, I implemented strategies such as designing posters and using stickers in order to keep classroom management. I implemented this strategy mainly with preschoolers and first graders. At the beginning, I used sad and happy faces; however, after some time, I began to use only happy faces with the students, and I noticed that this worked much better than using sad faces. (Daniela, Narrative Interview 2)

The participating teachers suggest that the experiences they underwent in their respective jobs allowed them to rely on classroom management strategies along with more situated practices. They remark that these actions were beneficial for the development of their teacher identity. Concerning this, Castañeda-Trujillo and Aguirre-Hernández (2018) have suggested that the teaching practicum helps student-teachers develop a more sensitive understanding of their own classroom. Regarding teacher’s reality shock, Bridges (1980, as cited in Caires et al., 2009, p. 17) describes entering the profession as a “normal process of disorientation and reorientation, which marks the turning point in the direction of growth.” Consequently, teachers’ adaptability and renegotiation of their teaching practices gains importance in the ongoing construction of their identity as EFL educators.

Equally important, participants expressed becoming aware of the need for continuous professionalization and provided distinct characterizations of themselves as EFL teachers before the master’s in ELT.

I decided to do the master’s program because one needs to continue gaining knowledge. Pursuing master’s studies also contributes to one’s professional development, living status, and life quality. . . . I was less critical about education in general. I have learned that, as a teacher, you have to show students the reality, the truth. I think that English becomes a point of reference for students; if they see a critical person in front of them, they will indirectly learn to be critical and generate social awareness. (Daniela, Narrative Interview 2)

I consider I was a less confident teacher. I was also less reflexive. Before, I could get frustrated much more easily as preconceptions created in my time as a university student did not allow me to see other things. (Angela, Narrative Interview 2)

We perceived that participants had several reasons for enrolling in a master’s program. Professional development opportunities along with better job chances were some of the most common among them. This is evidenced in Daniela’s and Angela’s comments who posit that they were less critical and reflective about education in general before their postgraduate academic experience. For Viáfara and Largo (2018), teachers’ participation in master’s programs is beneficial because this postgraduate experience can provide them with new methodological and instructional trends. Furthermore, the overall master’s degree experience appears to have helped teachers move from what Kumaravadivelu (2003) called “the passive technician” period to what he also named as the “reflective” stage, since continuous exposure to updated trends in the language teaching field also allowed the participating teachers to develop more critical/reflective skills in relation to their own teaching roles.

Contribution of the Master’s Program in ELT to EFL Teachers’ Professional Identities

This second category deals with the contributions derived from studying a master’s program in ELT in relation to the identities of participating teachers. The analysis was carried out based on the information gathered from the second and third oral narratives and interviews with the participants.

Finding Value in the Other

All teachers underscored the inherent value of their interactions with other classmates (former students of the master’s program), their professors, and other professionals within the ELT community of their programs. They referred to experiences lived in different contexts, through diverse strategies and teaching practices of their colleagues. Part of this enabled them to shape their own identities as language educators and professionals. The following excerpts exemplify the aforementioned points:

Getting to know other contexts is good as, in that way, I could notice I was not alone. There are other people facing the same difficulties as me. That experiential issue was enriching as a professional. (Julio, Narrative Interview 2)

When I talked to my classmates, I could also see the reality they were living in their schools, what they did, and the kind of students they had. (Daniela, Narrative Interview 2)

Based on Gee’s (2000) view, teachers’ continuous sharing of contextual experiences influence others’ identities as educators in what he calls institutional identity. This was reflected in all participants’ claims as they admitted that their colleagues’ experiences had influenced them to the point that they had begun to become aware of the challenges, needs, and lessons other teachers had in their own immediate teaching contexts. Likewise, the participants referred to experiences with professors and classmates from the master’s program that they found beneficial for their academic and professional growth.

My thesis advisor was an excellent professional. She was always willing to collaborate with the simplest and with the most complex doubts I had about the project. I think having selected her as my thesis advisor was a factor of motivation to continue working on the project. (Julio, Oral Narrative 2)

I think that sharing with the professors was fundamental regarding our teaching identity. Although the first experience with one of the professors in terms of research was kind of shocking as she was not fully aware about the context of the master’s, I think that the human quality of most of the professors was high. (Fernanda, Narrative Interview 2)

The participating teachers highlighted the human quality of their professors, often reflected through cordiality and willingness to teach, and by clarifying their doubts in and out of the classroom. Although there were also a few accounts of negative situations with some of them, all experiences draw on the impact that such events generated on the participants’ motivation and learning attitudes. Positive experiences with their professors made them feel more comfortable and confident to learn, to ask questions, to participate more actively in class. On the other hand, negative experiences triggered lack of motivation and uncertainty towards the process, making them more reflective of the need for good traits and the importance of an appropriate classroom environment.

Becoming Empowered Critical Reflective Educators

Teachers claimed that they became more reflective educators, eager to take action and change the realities of their own contexts. Part of this eagerness was also promoted by the orientation received in their courses and the influence that these generated in their perceptions as language educators. Participants’ insights suggest that witnessing their professors’ pedagogical strategies in the classrooms led them to be actively involved in pedagogical processes at their university (as students) and in their respective workplaces (as teachers).

Most of the courses allowed us to reflect upon our context in a more profound way. Also, they enabled us to see things we did not see before. (Angela, Narrative Interview 2)

Some courses were related to language learning, bilingualism, how languages interact within the social dimension, and how research contributes to the development of society. Others were related to curriculum, how it works within the classroom [as well as] assessment with its components: self-assessment, peer-assessment. (Julio, Narrative Interview 2)

Participants acknowledged that the influence exerted by these courses impacted their teaching practices positively and encouraged them to design and implement new ones in their local contexts. Such implementations not only transcended traditional classroom procedures, but also equipped them with new views of their teaching realities. As suggested by Angela, although certain things had always been present, they had not been visible to them in the past. Thus, experiences of this kind made participants engage in more critically self-oriented reflections, as they could “begin to see” aspects which had never been noticed before.

A robust body of academic literature supports the idea that continuous teacher’s professionalization does not only contribute to improving teaching practices, but also allows teachers to be in contact with the newest trends within the ELT field (Coldwell, 2017; Farrell, 2013; Freeman, 1989). In this case, teachers’ renewed practices are prone to combine global elements with local needs, resulting in what Kumaravadivelu (2008) called “glocalized” practices. This is especially portrayed in Julio’s and Angela’s data where they comment that the readings they made, along with other class related experiences, led them to analyze their own immediate contexts in light of their newly acquired knowledge.

Widening the Spectrum: Understanding Teaching From a Renewed Perspective

In addition to the aspects explained above, we found that teachers developed a renewed perspective on language teaching and research in education. They recognized themselves as agents of social change and developed other dimensions of their teaching identities. The following excerpts display “a renewed sense of teaching and the teacher persona,” which presents teachers’ insights on their participation in the master’s programs and situations which made them change their views on teaching and their own self as educators.

When I finished the master’s program, I had more experience in terms of teaching, I had known more contexts, I had already overcome many of the difficulties I had at the beginning. Also, my level of commitment is higher. I feel that being a teacher is not only a job, but also a responsibility. (Angela, Narrative Interview 2)

I feel as a more experienced teacher, a person with a higher level of expertise in terms of qualitative, quantitative research. Now I know how to do research, how to formulate a research question, how to contribute to my educational context, and [I have] the desire to continue growing as a professional. (Julio, Narrative Interview 3)

It is worth noticing that participants do not make distinctions between the teacher and the persona they are. Instead, they combine both elements, suggesting that the influence of the master’s program impacted more than one of their identities as individuals. This goes in line with Davis’s (2011) assertions, who claims that the teacher persona (understood as the role that individuals assume when they actively perform their role as teachers in educational contexts) is directly influenced by other experiences at the social, cultural, and academic levels. In addition to this, part of the data gathered from participants denotes situations where they exteriorize their social commitment at their institutions as part of their now reinforced social consciousness.

The teacher is also an agent of social change because you do not only teach about your subject, but you also transform your students’ lives. You educate, which makes your students change their way of thinking. Teachers show other realities, things that occur in the world, things that exist, and objectives that you can achieve. (Daniela, Narrative Interview 2)

English teachers not only teach English, but we also have an advantage over other teachers: having the capacity to read research in other languages, studies conducted in other contexts, and adapt them to our context. We have a big advantage as we work in all areas of knowledge through English and we are more receptive to difference, but we have not done enough. However, I believe that all the English teachers have the capacity to transform social realities. (Angela, Narrative Interview 2)

The previous excerpts show how participants reinforce the idea of English language teachers as agents of social change who contribute to education and social improvement in general. Indeed, participants have assumed a more critical-reflective position, where social related issues have gained relevance from their teaching perspective. They have moved from what Kumaravadivelu (2003) called “the reflective practitioner” to what he later came to call “teachers as transformative intellectuals.” Interestingly, teachers also recognized the importance of research as an essential component in education.

Doing research within the master’s was a very complex and nice experience. The project allowed me to become aware of the characteristics that primary school teachers have when teaching English. Also, through this experience, I learned to be more organized. (Angela, Narrative Interview 2)

When I come across a problem, I immediately think of how I could address it from research. (Angela, Oral Narrative 3)

Doing research for me was an enriching experience because it allows you to see things differently. Gathering and analyzing the data is a very interesting process. Nowadays, I keep doing research, but with a different scope. (Fernanda, Narrative Interview 2)

In support of this analysis, Barkhuizen (2016) argues that teacher’s identity is a fluid and negotiated complex process which is constantly evolving based on varied experiences. Thus, participation in academic contexts becomes crucial to widen teachers’ understanding of their teaching selves as these are subject to be reshaped based on their immediate academic lessons (as students and with their own students; Barkhuizen, 2017; Danielewicz, 2014). Opportunities given by the master’s program in ELT and by the participants’ own working settings set a pathway for them to explore and understand language methodologies, research interests, and educational theories.

Conclusions

Firstly, the study shows that early educational experiences allowed teachers to recognize and develop similar behaviors to those of their previous teachers. However, as they gained more experience, they were able to detach from these practices to develop their own (authentic) pedagogical philosophies. Thus, providing constant exposure to teaching opportunities, methodologies, and procedures is essential for the initial teacher’s identity construction. Likewise, we established that, although constant exposure to academic experiences played a fundamental role in LTI’s initial construction process, sociocultural and community-based involvement permeated other dimensions of the participants’ teaching selves. In view of this, examining these elements inside and outside formal and informal contexts, and the relation these play in connection with LTI construction, is an aspect that deserves more attention.

Another conclusion is that although the participants believed their education at the level of undergraduate level did not contribute to generate a profound understanding of English teaching among indigenous and vulnerable communities, the MA in ELT provided them with new scenarios to share and reflect upon professional experiences, constituting therefore a turning conceptual shift by means of constant debates, exchange of ideas, mini-talks, paper discussions, and oral presentations. Hence, continuous exposure to socio-academic experiences was one of the most remarkable aspects that exerted greater influence on their identities.

Finally, the study also demonstrated that the participants’ level of reflection increased based on their participation in the master’s. This was portrayed in several instances (especially in the second and third oral narratives and narrative interviews) where participants manifested having learned about new trends within the ELT field, which subsequently triggered their interest in continuing learning about these elements to combine them with their own practices.

Implications for Further Research

This study sets the ground for other researchers to explore changes in teachers’ perceptions concerning the adoption and implementation of bilingual policies in Colombia, the construction of critical-reflexive perspectives towards language teaching, the understanding of interculturality and multimodality, and the promotion of professional development programs in other school contexts. These themes are paramount to develop a better understanding of the ongoing identity construction we all face in our teaching careers, the role played by postgraduate education in the consolidation of our teaching practices, and the pedagogical contributions that these programs provide to the teaching community in general.

In this line of thought, we would like to end by inviting other researchers to delve into the contributions in EFL teachers’ professional development process resulting from their participation in doctoral programs. We think the reasons that motivate EFL students to become language educators are also worth exploring. Studying these realities can give us a better outlook of an individual’s identity consolidation prior to or after becoming an educator.

To sum up, the implementation of this research project evidenced that teacher identity is not a fixed element, since continuous exposure to classroom experiences and social and academic interaction (Cooper & Olson, 1996) enrich teachers’ ongoing negotiating identities (Barkhuizen, 2016). Thus, much more research needs to be done at the level of this area of knowledge as there are teacher identity dimensions which remain unexplored.