Introduction

Due to the essential role of language teachers in the teaching profession, researchers have focused on the crucial factors that would improve their performance and, consequently, their effectiveness. Hence, it is of primary importance to identify factors contributing to language teachers’ effectiveness (Pishghadam et al., 2011).

In teaching literature, the word effectiveness seems to lack an explicit, straightforward, and robust definition. Hunt (2009) defined effective teachers as those who can teach their learners to be good and effective citizens in the future. Galluzo (2005) defined teachers’ effectiveness in relation to students’ success. If we focus on foreign language teachers, as this study does, there is at least one more variable to consider: teachers’ effectiveness is associated with the students’ competence in the foreign language. For Galluzo, teachers’ effectiveness plays a significant role in the students’ academic achievement and linguistic performance. He argues that effective teachers finish a course where the majority of students succeed in achieving the course’s goals. Therefore, the course’s objectives are important, and teachers’ effectiveness may vary in different courses and contexts and from one objective to another.

Therefore, exploring the characteristics of teacher effectiveness is essential for improving the quality and productivity of foreign language teacher’s training courses. Hence, the present study investigates the factors contributing to language teachers’ effectiveness in improving teacher’s training courses, leading to successful language learning programmes.

Literature Review

To date, researchers have investigated teacher’s effectiveness from different perspectives to shed light on the factors which play a key role in promoting teachers’ productivity and efficiency. Zamani and Ahangari (2016) defined effectiveness as what is perceived by a language learner in an English as a foreign language (EFL) context. Their definition focuses primarily on the quality and kind of relationship that teachers have with language learners. Furthermore, they concluded that effectiveness helps teachers have discipline in their classrooms, which is a fundamental aspect of teachers’ effectiveness. According to their study, discipline and the teacher-learner relationship come to the fore when investigating language teachers’ effectiveness. Similar research has been done on effectiveness, but none has provided a comprehensive definition of the construct that would involve all its contributing factors (e.g., Mitchell & Bradshaw, 2013; Pane, 2010).

Liakopoulou (2011) sees a good teacher as someone who is effective in how he or she teaches. She searched for the qualifications that contribute to a good teaching; however, she rightly argued that an explicit definition of a good and effective teacher is neither possible nor desirable because, essentially, it varies from one context to another. One of the factors that she mentioned, and which was absent in other studies, was the teachers’ experience. She claimed that experience could facilitate, to a large extent, their task and guarantee their effectiveness. Goodwin et al. (2019) acknowledged the importance of experience in language teachers’ effectiveness. However, in a longitudinal study, they concluded that experience and its effect on teachers’ performance were more significant in the first years of teaching. Afterwards, its significance decreases in an unprecedented scale. However, they found that language learners favour experienced teachers, and, in many situations, they see experienced teachers as the most effective ones.

An issue closely related to language teachers’ effectiveness is their assessment literacy and practice. Language teachers’ assessment literacy has recently received much attention (for a recent comprehensive review, see Coombe et al., 2020; Giraldo, 2021; Levi & Inbar-Lourie, 2020; Vogt et al., 2020). In a recent study, Kremmel and Harding (2020) highlighted the need for promoting language teachers’ assessment literacy. They also emphasised the need for further research in this field. Hao and Johnson (2013) investigated the relationship between the teachers’ use of different classroom assessment types (such as multiple questions, short answers, and paragraph writing) and oral communication across several classes in different countries. They observed that teachers’ assessment literacy helps them provide their class with an appropriate assessment frame that suits their objectives. Thus, their interpretation of the learners’ performance may be more valid in their evaluation of learners. More precisely, it seems that the teachers’ experience and education affect their assessment literacy and, consequently, their effectiveness (Asl et al., 2014).

When it comes to teacher’s effectiveness, content and pedagogical content knowledge is another issue that should not be neglected. Shulman (1987) first discussed pedagogical content knowledge and asserted that teachers needed to have curricular knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, subject matter knowledge, knowledge of students, knowledge of the school, and pedagogical content knowledge. Since then, many researchers have investigated these factors in various teaching contexts to develop measurement instruments (e.g., Han-Tosunoglu & Lederman, 2021). Three decades after Shulman’s seminal study, Grieser and Hendricks (2018) defined pedagogical content knowledge considering two subcategories: in-field and out-of-the-field pedagogical content knowledge. Out-of-the-field pedagogical content knowledge is when teachers’ preparation does not correspond to their teaching assignments. To have pedagogical content knowledge, teachers should be aware of the context and social norms that may contribute to the topic and to the subject matter they teach (Liakopoulou, 2011).

The construct of experience and its effect on students’ achievement has been examined in different contexts. However, considering experience as one of the effective teachers’ features is controversial. Harris and Sass (2011) studied the various types of teacher’s training courses and their productivity in promoting teachers’ effectiveness and students’ achievement. In their study, they equated teachers’ effectiveness with their productivity. The result of their study revealed that pre-service and in-service teachers’ productivity increases with experience; interestingly enough, it was observed that the increase was significant in the first few years.

Chambless (2012) claimed that many teachers whose content knowledge was sufficient were experts in the subject matter. However, their oral proficiency and their expertise in the content area were not evaluated, and this may affect the way that language learners welcome teachers. Therefore, it goes without saying that the teachers’ speaking skills is what makes the first impression on language learners. In a recent study, Faez et al. (2019) conducted a meta-analysis to examine the potential relationship between language proficiency and teaching ability. They observed a moderate relationship between language proficiency and teaching self-efficacy. Therefore, they concluded that self-efficacy should not be limited to the teachers’ language proficiency.

Moreover, the teachers’ personality in the classrooms has been considered a critical factor for success in their work (Santilli et al., 2011). To date, different subcategories of teachers’ personality have been studied (e.g., Akyıldız & Çelik, 2020; Li & Li, 2019; Oryan & Ravid, 2019; Sato, 2020).

Self-efficacy is another factor contributing to language teachers’ effectiveness, which has been extensively investigated in recent years (e.g., Choi & Lee, 2016; Moradkhani et al., 2017). As Wang and Sun (2020) rightly highlighted, since Bandura’s publication on self-efficacy in 1977, we have witnessed a growing body of research in this field. According to the research to date, self-efficacy is distinguished from teachers’ effectiveness, for self-efficacy is defined as the beliefs teachers hold about themselves. Therefore, it may be considered as a subcategory of language teachers’ effectiveness. The research findings support the pivotal importance of self-efficacy in teachers’ effectiveness (e.g., Hoang & Wyatt, 2021; Thompson, 2020; Thompson & Dooley, 2019; Thompson & Woodman, 2019).

The Study

As the literature indicates, language teachers’ effectiveness has always been a controversial issue in language teaching research. This issue is more critical in EFL contexts as there are few opportunities for practicing new languages. Although many people who live in EFL contexts may not find any opportunity to use English or any other foreign language, they are still willing to learn them. Due to an increase in the willingness to learn new languages, especially English, institutes and educational systems are looking for effective language teachers. They welcome teachers who can be categorised as successful and effective by their institutes (Noorbakhsh et al., 2018). That is why this study aims to explore language teachers’ effectiveness in an EFL context (Iran). We hope this study’s findings may shed light on the importance of effective language teachers in such contexts and how they are evaluated as effective. To this end, the following research question guided this study: What are the factors contributing to language teachers’ effectiveness in the Iranian language learning context?

Method

The present study was a mixed-methods study aimed at exploring the factors contributing to foreign language teachers’ effectiveness. The study was conducted in two phases. The first phase employed qualitative methods (theme analysis and interviews), and the second phase used a quantitative method (factor analysis) to answer the study’s research question.

Participants

In the first phase of the study, directed at extracting and verifying the factors contributing to teacher effectiveness, 13 EFL lecturers, as experts in applied linguistics, participated in this research project (one woman and 12 men). They were required to have a PhD, to have graduated from state universities and have at least three years of teaching experience at universities. These lecturers came from four state universities in Iran. They were considered experienced lecturers for their teaching experience at universities ranged from 5 to 40 years.

In the second phase of the study, which validated a teacher’s effectiveness questionnaire, 93 EFL teachers participated, ranging in age from 20 to 45 years. About 26.9% were men, and the rest were women. All of them had academic English degrees and were teaching in private-sector language institutes. Seventeen participants held a BA in English, and 76 held an MA in English language teaching. They were asked to report their years of experience in language teaching in institutes. The majority had less than five years of experience (about 34.4%). Twenty-nine per cent had between five to eight years of experience, 25.8% between nine to 12 years, less than 6% between 13 to 16 years, about 2% between 17 to 20 years, and the rest (around 2%) more than 20 years. They took part in the study through an online questionnaire shared in specialised groups on different social media outlets, namely Telegram and WhatsApp.

Procedure

Relevant Studies

The first instrument used to identify the factors contributing to language teachers’ effectiveness was the relevant studies. We tried to find the most recent and relevant studies published in the refereed journals in the field. The studies were reviewed and subjected to thematic analysis to extract the items related to the language teachers’ effectiveness to be judged by the experts.

Expert Questionnaire (Semi-Structured Interview)

Based on the thematic analysis of the literature review, 40 items were developed to be rated by the experts. These 40 items included statements about language teachers’ effectiveness. The constructs underlying this questionnaire (see Appendix A) were labelled as assessment literacy (Items 6, 12, 20, 24, 27, 29, 35), content and pedagogical knowledge (Items 2, 9, 11, 22, 31, 34), experience (Items 1, 17, 21, 30, 33), oral proficiency (Items 3, 5, 16, 26, 28, 39), personality type (Items 7, 8, 10, 13, 14, 15, 18, 23, 25, 37, 40) and self-efficacy (Items 4, 19, 32, 36, 38). We identified the major categories and their corresponding subcategories. The participants were asked to respond on a 5-point Likert-type scale (from strongly agree to strongly disagree). One open-ended question at the end of the questionnaire asked the respondents to provide additional comments.

Language Teachers’ Effectiveness: The First Draft Questionnaire

Based on the responses collected in the first step of the study, we came up with a 21-item questionnaire in the Likert scale format. Two new items were added: creativity, which was grouped under personality type, and first language (L1) use when considered necessary, classified as a subcategory of experience following the experts’ suggestions and comments obtained from the interviews. The experts’ comments and suggestions were also considered in reviewing items and their wording. Overall, 24 items were prepared at this stage. Then, the items were distributed among the English language teachers working at different institutes at this stage. The new questionnaire also included six constructs (see Appendix B). However, the number of items in each construct changed as follows: assessment literacy (Items 3, 10, 19), content and pedagogical knowledge (Items 4, 7, 15, 18), experience (Items 11, 17, 24), oral proficiency (Items 1, 2, 13, 14, 22), personality type (Items 5, 6, 8, 12, 21, 23) and self-efficacy (Items 9, 16, 20).

Results

An extensive and intensive review of the literature was conducted to extract a comprehensive list of factors contributing to language teachers’ effectiveness to address the study’s goal. After performing the review, six main categories were extracted (see Table 1).

Table 1 Factors Qualitatively Extracted From the Literature and From Interviews

| Factors | Example Study |

|---|---|

| Assessment literacy | Teachers’ assessment literacy will help teachers use more valid information about their learners to teach more effectively (Pastore & Andrade, 2019). |

| Content and pedagogical content knowledge | Teachers should be aware of the context and the appropriate instruments and techniques they might need for more effective and transparent lesson presentations (Liakopoulou, 2011). |

| Experience | The role of experience in teachers’ effectiveness is more significant in the first years of teaching (Staiger & Rockoff, 2010). |

| Oral proficiency | Language teachers’ oral proficiency is considered to be the first impression on learners. It can affect the way learners welcome a teacher (Chambless, 2012). |

| Personality type (subcategories: creativity, extrovert vs. introvert, discipline, gesture, flexibility) | Personality is an indivisible part of the effects that teachers have in any educational system, and it is one of the key factors in their effectiveness (Penner, 1984). |

| Self-efficacy | In many studies, researchers have tried to find factors contributing to teachers’ self-efficacy and, therefore, to their effectiveness. For instance, the effect of the teachers’ language proficiency on their self-efficacy (Choi & Lee, 2016). |

After the experts rated the items presented to them, those items obtaining more than 80% agreement from experts (Items 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 13, 19, 20, 21, 25, 26, 28, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39) were selected to be included in the first draft of the questionnaire, which would be distributed to the EFL teachers. Besides these 21 items, three items were also added following the experts’ suggestions and comments. They were about teachers’ creativity and the L1 use in classrooms. About 10 (out of 13) experts suggested teachers’ creativity be included, and eight mentioned that appropriate L1 use in language classrooms should be considered in an EFL context. In Appendix B, creativity (Items 6 and 23) and selective use of L1 (Item 24) have been added to the 21 previously extracted items. The main categories of these two items were also discussed with the experts suggesting them. Creativity was then defined as one of the subcategories of the personality type and selective use of L1 was considered one of the subcategories of experience. A Chi-square analysis was conducted to obtain the Iranian EFL teachers’ attitude towards factors contributing to the effectiveness of language teachers (see Table 2).

Based on the analysis, the agreed sample adequacy is 0.6 or above. According to Table 2, sampling adequacy was about 0.57, close to the one agreed upon (0.6). Regretfully, because of the situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, it was impossible to collect more data during this phase. Subsequently, we decided to accept this value and continue with the study. Additionally, Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity value should be 0.05 or smaller; Table 3 shows that it was .000, that is, Bartlett’s test was significant, so the factor analysis was appropriate.

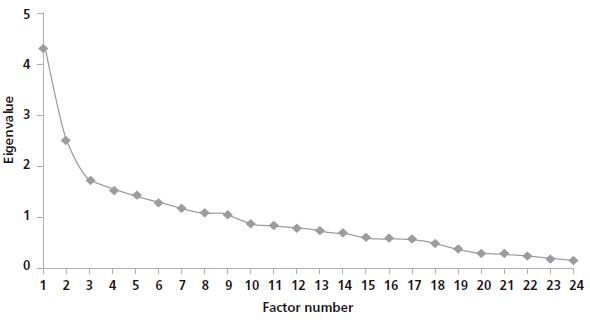

Table 3 verifies a good level of reliability for the questionnaire. Accordingly, the reliability of the items was .775, which is acceptable. Figure 1 confirms that nine factors were above one. Therefore, it can be concluded that the nine factors were extracted. In Table 4, the item’s loading factor is also provided.

Table 4 Results From Factor Analysis of Language Teachers’ Effectiveness Questionnaire

The items excluded from Table 4 (Items 7, 12, 18, 20, and 24) were not found appropriate for the questionnaire. According to the results, Items 7, 12, and 18 had no loading in any factors or in any other items. Item 20 loaded negatively only in Factor 5, and Item 24 loaded in three factors, all negative. In this table, the factors and their items were confirmed. We then concluded: factor one included Items 1, 2, 13, 14, and 22 for oral proficiency. Factor two included Items 5, 6, 8, 21, and 23 for the personality type. Factor 3 was eliminated because only two items were loaded negatively (Items 4 and 15). Factors 4 and 5 included two items (9 and 16 in Factor 4; 11 and 17 in Factor 5), which measured the content and pedagogical content knowledge and self-efficacy. Factor 7 was also eliminated because only one item was loaded negatively. Factor 8 included Items 3, 10, and 19 related to assessment literacy. Item 1 loaded in Factor 9, but as it was loaded in Factor 1 and was related to the other items loaded in the same factor, it was decided to ignore it and finish the table with six factors: 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8. We finally developed the final questionnaire with 18 items (Appendix C).

Discussion

This study attempted to explore the factors contributing to language teachers’ effectiveness in an EFL context and develop a questionnaire involving constructs in this definition. After developing 40 statements according to the literature review, personality type had the most items. Eleven items were included for personality type, seven for assessment literacy, six for content and pedagogical content analysis, six for oral proficiency, five for experience, and five for self-efficacy. In the following questionnaire, which included 24 items, most items pertained to personality type (personality type = 6; oral proficiency = 5; assessment literacy, experience, and self-efficacy, each got three; and content and pedagogical content knowledge = 4). According to the literature, it was expected that more items would be devoted to personality type. However, in the final questionnaire (see Appendix C), with 18 items selected after factor analysis, the number of items for personality type and oral proficiency was the same. Each had five items. Evidently, based on the results, teachers’ personality is arguably an indivisible part of teacher’s effectiveness (Santilli et al., 2011).

The interesting point about personality type is that two items of creativity remained in the final questionnaire. Therefore, it confirms Li and Li’s (2019) point that creativity is an essential factor for language teachers’ effectiveness. It may be concluded that language learners and language institutes should look for innovative teachers regarding teaching activities and strategies. Such innovation allows teachers to be more prepared for their classroom, and to offer students attractive and motivating lessons. Otherwise, they might be considered boring teachers with no specific techniques and strategies. As Li and Li have mentioned, creative teachers can produce creative language learners; those who can think outside the box (Akyıldız & Çelik, 2020).

Oryan and Ravid (2019) see good teachers as those who are open to new methods and strategies. While developing the questionnaire, we realized that two important teaching strategies, often overlooked, have to do with the teacher’s body language (gestures) and discipline management. As many researchers (Bowcher & Zhang, 2020; Fatemi et al., 2016; Sato, 2020) rightly argue, teachers’ care of their gestures and nonverbal behaviour is strongly associated with their success and effectiveness. Moreover, another factor under this category is the teachers’ discipline, presented as teacher’s punctuality. It has benefits for students, but it also helps teachers manage their classrooms effectively (Jeloudar & Yunus, 2011). The only remaining point in teachers’ discipline and personality type is the teachers being “extrovert vs. introvert.” According to Fatemi et al. (2016), students favour extroverted teachers, those who show their care for students through verbal and nonverbal behaviour. However, the results showed that teachers are not so interested in considering this aspect as part of their effectiveness. The item developed for this aspect did not obtain enough agreement to be included in the final questionnaire.

Regarding teachers’ oral proficiency, and as Bateman (2008) has shown, the recent passion for developing speaking skills when learning new languages has affected attention to oral proficiency in teachers and learners. Further, Chambless (2012) has mentioned that teachers lacking oral proficiency, but being experts in the content area, may be less welcomed by language learners. This result shows a similar finding and shows that teachers are aware of the need of language learners to be proficient speakers. Oral proficiency obtained five items in the final questionnaire (the same as personality type).

The next factor with three items is assessment literacy. In the pilot phase of the questionnaire, none of its items was deleted. It shows that the respondents believe they have enough knowledge of this factor and that different approaches are vital for a language teacher’s effectiveness. Considering the factors agreed upon by experts and language teachers, three aspects of assessment have been included: teachers’ fairness, course objectives and mutual relationship between assessment and class productivity. According to Hao and Johnson (2013), if teachers take into consideration course objectives in their assessments, their interpretation shall be more valid, and their class productivity improved. These items have been validated in the final questionnaire. Teachers’ fairness is affected by their experience (Asl et al., 2014). Due to the relationship between experience and assessment, when considering experience items in the questionnaire, we observed that using colleagues’ experience and teaching and learning experience help language teachers to be fair and effective.

In the relevant literature, teaching experience was considered a controversial factor for language teachers’ effectiveness. Harris and Sass (2011) hold that experience positively affects teachers’ effectiveness during the first years of their profession. Henry et al. (2011) confirmed that it derives from a sense of satisfaction that preservice language teachers feel as they obtain a wider experience during the first years of teaching. However, one point should be kept in mind. The number of years is important for a teacher to be considered experienced, and so is the number of classes and courses they have held. A teacher with two years of experience having had a maximum of six sessions per week is not the same as a teacher having the same years of experience but 18 sessions per week. We therefore decided to include teaching experience in the questionnaire, but no clear criterion regarding the number of teaching years was provided. Only Item 24 in Appendix B was eliminated after the pilot. Considering the remaining items, it may be concluded that experience and its effects are not limited to the first years of teaching. One of the items is “using colleagues’ experience” because even experienced teachers may use their colleagues’ experience for teaching new classes.

Content and pedagogical content knowledge, self-efficacy, and experience had the same number of items (two items each). In the literature, content knowledge and the ability to effectively present that knowledge to audiences was considered necessary. It was mentioned that teachers have many sources from which to obtain content knowledge, such as preservice training and in-service courses, to name but a few (Grieser & Hendricks, 2018). Interestingly, content and pedagogical content knowledge lost two items during the pilot phase. Since the research’s target was language teachers’ effectiveness, this is a point that should be further analysed. One reason for this loss may be the easy access to many sources to obtain knowledge, such as websites and educational applications. Therefore, if teachers are not sure about some aspect of language, such as idioms or similar issues that are mainly cultural, they may ask students to research them or develop a project, and even devise some tasks. Thus, we believe that easy access to content knowledge explains why this factor did not obtain many questionnaire items. However, this does not apply to knowledge of words and grammar; they are the basis of the content knowledge that each language teacher should have.

Finally, we identified the self-efficacy factor. According to the literature review, language teachers’ self-efficacy is directly and indirectly affected by many factors (Afshar et al., 2015), such as teaching experience and language proficiency. Based on Moradkhani et al. (2017), we initially decided to include one item related to the relationship between reflective thinking and self-efficacy. Item 20 in Appendix B represented this relationship, but, interestingly, this item was deleted during the pilot. This seems to show that language teachers did not see reflective thinking as an integral part of their self-efficacy and, consequently, of their effectiveness as a whole.

Conclusions

The main output of the present study was to validate a questionnaire on language teachers’ effectiveness that other studies may use to address this issue in similar contexts. Furthermore, the main contribution of the present study to the growing body of research on the promotion of teacher training courses is that it develops an understanding of language teachers’ effectiveness from their own point of view. This study was an attempt to make language teachers look at their effectiveness and to promote their vocation. The data collected from this study, highlighted in the literature, investigated factors related to language teachers’ effectiveness and tried to categorise them into major themes. The relatively high number of items for oral proficiency shows the importance of this factor in language teaching. Oral proficiency and language teachers’ ability to speak and communicate the target language well is fundamental for effectiveness. Furthermore, to be effective, a language teacher not only should be competent in one area like language usage, but also should care about personality, verbal and nonverbal behaviour, assessment literacy, self-efficacy, oral proficiency, and other factors that may be needed in the particular teaching context. In most factors, professional experience plays a role. However, the number of years by itself cannot predict teacher’s effectiveness, for it depends largely on the person’s engagement. A teacher might be in this profession for a short period of time but be more committed, while another might have been teaching for a long time but is less engaged.

Primarily, this study attempted to encourage teachers to be aware of the multiple aspects effectiveness in their profession has. This study’s findings can be informative and useful for language teachers and stakeholders directing institutes, teacher training courses, and teacher education programs in academia. As seen in the review of the literature, language teachers’ effectiveness is a multi-faceted construct, and teachers should not improve one aspect at the cost of others. They should think about their effectiveness and try to improve their weak aspects. According to the findings of this study, it is highly recommended that teachers develop their speaking skills, as it is the one skill that leaves a lasting first impression on their learners. Meta-cognition is also recommended so that teachers are more responsible in their evaluations and consider how they affect their classrooms’ productivity. Furthermore, educational institutions can use a teachers’ self-evaluation to compare it with their classroom achievement results. Such comparisons may be used to improve the productivity of training programs, teachers’ effectiveness, and language courses.

It is suggested that future researcher investigates the validity of our questionnaire in an array of similar and different educational contexts. We need more studies on the contextual and ecological variables that shape teachers’ effectiveness. We also need mixed-methods longitudinal cross-sectional research to have a more complete and accurate picture of teachers’ effectiveness in the long term. The outbreak of COVID-19 tested teachers’ computer literacy as online platforms made education possible. Accordingly, this research field should also include technological pedagogical content knowledge as a variable, for it is considered a crucial skill required from teachers who use digital technologies (Schmid et al., 2021; for a recent review, see Njiku et al., 2020). It is suggested, therefore, that researchers study foreign language teacher’s effectiveness in various contexts as research in this field is still in its infancy in terms of conclusive findings.