Introduction

Teacher education has shifted from teachers’ learning as observable behavior, to the cognitive mental processes in which they are involved, to the interaction of teachers in their contexts with other educational agents and processes (Grossman et al., 2009; Johnson, 2009; Oosterheert & Vermunt, 2003; Putnam & Borko, 2016; Tsui & Law, 2007). Teacher education emphasized prescriptive concepts about how and what teachers should learn, a perspective informed by the “dualistic understandings of the relationship between thought and action which seeks proof of the transfer of learning through the evident application of knowledge” (Ellis et al., 2010, p. 1). Thus, teachers’ practices are often determined by their behavior through perceptions and knowledge, work environment, and institutional policies (Goh et al., 2005; Richards & Lockhart, 1994).

More recently, Kumaravadivelu (2012) held that changes in society, such as globalization, make restructuring and re-conceptualizing teacher education imperative, particularly English language teacher’s education. Also, in order to empower teachers to become strategic thinkers who can theorize from their practice, it is important to design comprehensive teacher education programs.

The literature available also considers teacher’s education to include learning as cognition, reflection, and construction of identity as mainstays for better in-service teaching practices (Borg, 2015). This occurs with novice teachers through shifts in identity during practice (Kanno & Stuart, 2011; Quintero-Polo & Guerrero-Nieto, 2013; Thomas & Beauchamp, 2011), by working in different cultural settings (Block, 2015), or through social negotiations, knowledge and action, as well as ideological, political, and cultural inclinations (Fajardo-Castañeda, 2011).

The British Council (2019) proposed the continuing professional development (CPD) framework for teachers, consisting of four stages and 12 professional practices. These include activities such as planning, managing, and assessing learning and taking responsibility for professional development. CPD depends on teachers’ self-motivation and awareness of their professional needs to engage in appropriate professional growth opportunities. This could be problematic if professional development is seen by teachers, especially in the public-school sector, as a self-financed burden (Maussa-Díaz, 2014).

In Latin America, Chile has established the standards for English language teacher education (Estándares para carreras en pedagogía en inglés) focusing on two dimensions: disciplinary and pedagogical. The disciplinary standards focus on knowledge of the language and second language learning theory (Ministerio de Educación, República de Chile, 2014). The pedagogical standards center on theoretical knowledge of teaching-learning processes, including planning, teaching, and reflecting on classes, and curriculum-related aspects such as evaluation and design of materials.

In Colombia, similar attempts to establish a professional development framework for pre-service English language teachers started in 1991 with the Colombian Framework for English (COFE) project, a joint initiative between the Colombian government and the British Council. The project provided a group of universities with curricular reforms and standards for language proficiency, preparation in methodology through observation, co-teaching and internships, theoretical foundations for teaching English as a foreign language (EFL), and evaluative processes (Rubiano et al., 2000).

However, González et al. (2002) concluded that EFL schoolteachers’ needs for professional development went beyond theoretical knowledge and language proficiency. Paradoxically, teachers’ conception and sources of professional development center on optional training led by experts, training received in undergraduate studies, professional conferences, and publishers’ sessions (González, 2003), which are sources of professional and procedural knowledge. Similarly, Cárdenas et al. (2010) concluded from their review of professional development in Colombia that teachers need more reflective teaching practices rather than training. The authors also urged professional development for EFL teachers to be guided by post-method theories and meaningful practice.

Colombian researchers suggest a more critical professional development is needed (Buendía & Macías, 2019; Cárdenas et al., 2010; Cote-Parra, 2012; Cuesta-Medina et al., 2019; Insuasty & Zambrano-Castillo, 2010; Olaya-Mesa, 2018; Rodríguez-Ferreira, 2009; Viáfara & Largo, 2018). However, evaluations of in-service language teachers’ practice do not reflect this, nor allow reflective aspects of teacher practice to be identified. As expected, literature on in-service teachers’ evaluation in Colombia is scarce, with a few studies centered on public school teachers’ theoretical knowledge and classroom management (Figueroa et al., 2018; Lozano-Flórez, 2008; Novozhenina & López-Pinzón, 2018).

In this study, we shall try to identify specific critical and reflective aspects of teaching practices that respond to the previously highlighted needs in professional development in Colombia, by taking an already suggested critical teacher education model and applying it to teacher’s evaluation from the classroom level outwards. By doing so, we may understand what teachers are doing and why, and how they and others perceive their practice.

Literature Review

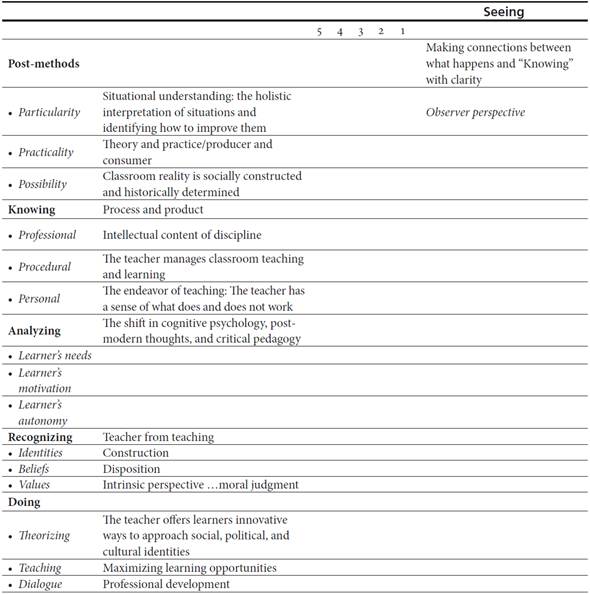

In this section, we introduce the “Knowing, Analyzing, Recognizing, Doing, Seeing (KARDS)” model (Kumaravadivelu, 2012) and its relevance to teacher evaluation by comparing and contrasting its constituent elements to other teacher evaluation models, focusing on those currently in use in Chile and Colombia.

KARDS Modular Model

In this section, we describe each of the components of Kumaravadivelu’s (2012, p. 125) modular model of language teacher education for a global society: KARDS.

Knowing

Knowing is the process whereby teachers are capable of acting upon r and reflecting upon their actions based on the combination of professional, procedural, and personal knowledge. Professional knowledge is discipline-related, and it encompasses knowledge about language learning and teaching. Procedural knowledge represents the teachers’ ability to manage classes efficiently. Lastly, personal knowledge is the teachers’ ability to transform their identities and beliefs as a result of reflection, experiences, and observation of their context.

Furthermore, the TESOL’s standards for ESL/EFL identify eight performance-based standards that “represent the core of what professional teachers of ESL and EFL for adult learners should know and be able to do” (Kuhlman & Knežević, n.d., p. 6). These are planning, instructing, assessing, language proficiency, learning, identity in context, content, commitment, and professionalism. Likewise, TESOL standards for K-12 teacher evaluations include content knowledge (language and sociocultural knowledge), pedagogical knowledge (instruction and assessment), learning environments, and professional knowledge (Kuhlman & Knežević, n.d.).

In Colombia, the Ministry of Education’s evaluation of primary and secondary in-service teachers in public schools focuses on professional, personal, and procedural knowledge. This mandatory evaluation process focuses on functional competencies (pedagogical knowledge, curriculum related duties, design, and evaluation) as well as behavioral competences (values, leadership, teamwork, social and institutional commitment, interpersonal relationships; Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN], n.d.). The moments where the evaluations take place are entry to the system, trial period, and yearly performance and promotion led by the schools’ principals. Class videos, students’ evaluation of teachers, and observations account for the teachers’ competences, and their compliance with their duties and the school’s policies. This evaluation aims at identifying weaknesses and strengths that favor the development of work and pedagogical competences that guarantee the permanence of the ideal teacher (MEN, n.d.).

Analyzing

Analyzing is the teacher’s skill to recognize and determine learner’s needs, motivation, and autonomy. Learner needs is what students want, need to achieve, and have not been able to achieve. Learner motivation is the students’ drive to learn a second/foreign language, whether this comes from a desire or a need. Learner autonomy is the students’ agency in their own learning process.

One system that may uncover aspects of analyzing is Chile’s system for the evaluation of professional teaching performance (Sistema Nacional de Evaluación del Desempeño Profesional Docente, SNED) for public primary and high school teachers. SNED is aligned with the national standards and consists of a portfolio, a third-party recommendations report, a three-question interview with a trained evaluator (peer) and a self-assessment report (Ministerio de Educación, República de Chile, n.d.). This latter instrument includes 12 yes-no questions about the students’ critical and reflective thought, self-assessment, curiosity, and autonomy, and whether and how teachers’ practices foster them. However, yes-no questions might elicit expected answers and not classroom realities regarding autonomy and motivation.

Recognizing

Recognizing indicates the teacher’s standpoint regarding the classroom. It is the ability to recognize the teaching self (composed of identities, beliefs, and values) and to renew it. Teacher identity is the persona displayed in the classroom and to other people in the teaching context. Teacher beliefs refer to conceptual ideas and theories on teaching that tell the teacher what a “good class environment” or a “good teaching of grammar” are. Finally, recognizing includes teacher’s values, which are related to the teachers’ moral agency and the challenges posed by rule compliance and caring for students. In our review, we have not found an in-service teacher evaluation system that focuses on this crucial dimension.

Doing

Doing refers to “classroom actions”; the teachers’ choices when approaching a classroom situation. It is a critical response process to the constant changes, multiplicities, and possibilities to create meaning. Doing encompasses theorizing, dialogue, and teaching. Theorizing indicates the teachers’ sensitivity to introducing appropriate changes to issues arising in the classroom. It is the antithesis of one-fits-all solutions to classroom issues. Dialogue is the ongoing and analytical processing and discussion of practice with oneself and with others that leads to personal and professional growth. Teaching refers to the ability to magnify and multiply the opportunities for students to learn, and to foster growth beyond textbooks and knowledge of a second/foreign language.

Chile’s SNED interview with a peer is meant to evaluate teachers’ ability to reflect on their practice, using scenario-like questions grounded on procedural and professional aspects of the teaching-learning context (e.g., what do you do when one of your students is not interested in your class?). However, the questions’ orientation toward the whats and not the whys may be favoring an orientation of teaching to outcomes (Garcia-Chamorro & Rosado-Mendinueta, 2021; Pinar & Irwin, 2004).

Seeing

Seeing is “perceptual knowledge,” the application of knowledge to connect agents to action and vice versa (i.e., the lived experiences). Seeing encompasses the teacher’s, the learner’s, and the observer’s perspectives. Teachers’ perspective is their evaluation of what happens in the classroom from a multifaceted position of control. The learner’s perspective provides information about the learning experience from an active position in the learning process. Finally, the observer’s perspective provides a critical outlook on teachers’ practices and how these impact the students’ learning.

Boraie (2014) noted that teacher effectiveness could be determined through observations, students’ evaluations, self-report systems, and evidence of learning. Hence, the multiplicity of factors included in successful teaching and the need for multiple instruments with various evaluation scales and perspectives should be recognized.

Thus, as checklists become longer, and expectations broader, teacher evaluation systems, such as the MEN’s, tend to scare teachers into passivity and accommodating behaviors of compliance, rather than challenging them to continuously work on their personal and professional development. Although a set of evaluative factors is important to include inside larger-scale evaluation systems that center on student learning, it is likely that such systems become top-down reflections only of the macro-level’s mostly punitive visions and missions. Similarly, self-motivated and less punitive systems such as the British Council’s CPD might fail to identify critical aspects of teachers’ practice since they lack the students’ and others’ perspectives, which are considered essential in successful teacher evaluations (Boraie, 2014). Instruments like Chile’s SNED interviews, with simulated situations of teacher’s practice, may be eliciting rehearsed command of procedural knowledge and failing to represent tokens of critical teaching practices.

Therefore, we believe that by adapting the KARDS language teaching framework and by creating an evaluation tool using the key ideas in these three perspectives (teacher, observer, and student), we could identify more specific areas for teacher professional development in Colombia. Thus, our research question is: How can the KARDS model be used as a teacher evaluation tool for reflective and critical practice?

Method

This interpretative case study examined the practices of in-service EFL teachers through observation, reflection, and student evaluation. Case studies allow researchers to expand and generalize theoretical propositions (Yin, 2018); our case study was directed at exploring, from different perspectives, the pertinence of the KARDS model as a teacher evaluation tool.

Research Context and Participants

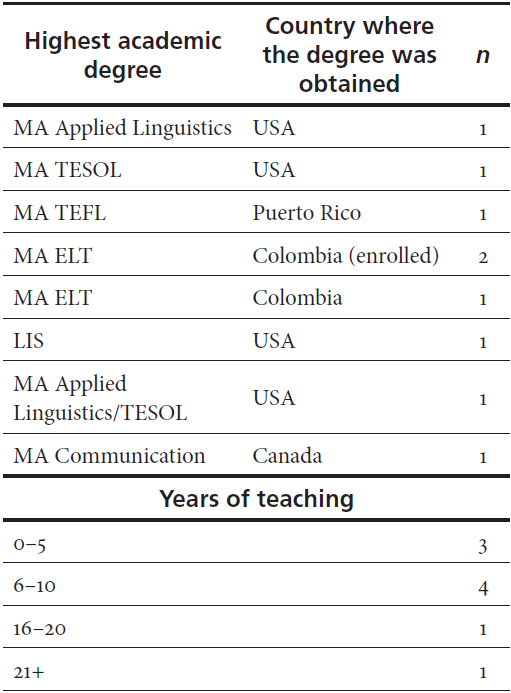

The participants in the study were EFL teachers and their students at a private university in Colombia. An email that introduced the project and its commitment level was sent to all the English language faculty (N = 90) encouraging participation in the study, to which nine teachers agreed. These teachers’ academic and professional experience ranges from one to over 20 years, with various master’s degrees including English language teaching, TESOL, applied linguistics, and other areas of humanities (see Table 1). In total, the nine participating teachers imparted lessons to 121 students. These students were also contacted (by email) and informed about the nature of the study.

Data Collection Instruments

The instruments used for data collection and analysis were the following:

Teachers’ Survey. The survey contained closed and open-ended questions (see Appendix A) regarding their academic and professional experiences. The open-ended questions included what the teachers considered their greatest strengths, areas for improvement, their theory of practice or approach to language teaching, and their self-perceptions within the classroom.

Teacher Reflective Journal. Participants worked freely on the journal procedure and reported either every other Friday for eight weeks or every third Friday for 12 weeks. For convenience’s sake, each participant shared a Google Drive folder with researchers. The questions aimed at eliciting information on the teachers’ day-to-day practice that reflected each of the modules of the KARDS model. Knowing and doing were placed together to encourage full answers (see Appendix B).

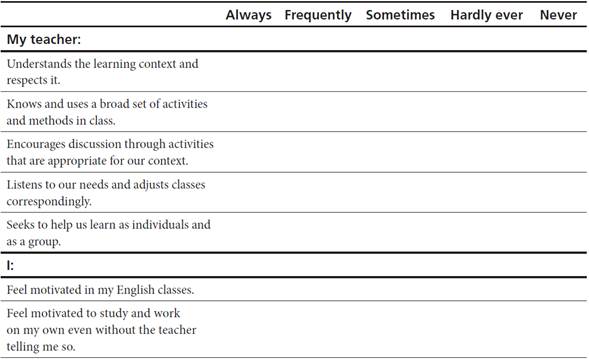

Students’ Questionnaire. This questionnaire aimed at capturing the students’ perception of the learning process and how the teacher fostered it. It included eight statements related to learning and teaching processes in their English class, along with a scale with five levels of frequency (see Appendix C) and an open-ended question on the students’ perception of their classroom learning experience.

Observations. Classroom observations lasted one or two hours. The teachers were observed at least twice during the eight weeks. We encouraged the teachers to plan classes as usual. The goal was to identify specific features in the teachers’ practices and determine whether they reflected or not traits of the KARDS model in the classroom.

KARDS Rubric. The data collected were analyzed through content analysis using the a priori categories provided by the KARDS model. The three perspectives (teacher, learner, and observer) were the methods of collection and triangulation of the data indicated by S (Seeing; see Appendix D). To help us meet the study’s objectives, we created a checklist that incorporated the components in each KARDS’s module, based on the three principles of the post-method pedagogy: (a) practicality, which refers to the practice of teacher-generated theory; (b) particularity, or the understanding of the political and sociocultural particularities of the learning context; and (c) possibility, associated with critical pedagogy that contributes to raising sociopolitical awareness among participants (Kumaravadivelu, 2012). Criteria were established to quantify the degree to which each trait or behavior of the component was met. A high degree of reliability was found among the raters’ measurements. The average measure interrater correlation coefficient was .909 with a 95% confidence interval from .779 to .976 (F (8,56) = 11.00, p < .001).

Procedure

First, teachers completed the survey and kept their reflective journal. The observations were made concurrently during the semester, depending on the teacher and the observers’ availability. Each teacher originally sent specific dates and class times to the observers, and the observers agreed upon who and when they were going to observe. Observations of teachers were categorized quantitatively and additional notes detailed further key aspects of the teachers’ practices and aspects of the KARDS’ model that checking the boxes would not have provided.

Findings and Discussion

This section shows and discusses the results of the data analysis from the three perspectives: teachers, observers, and learners. We shall highlight patterns of elements of KARDS found in each one of the perspectives.

Teachers’ Perspective

Teachers’ Survey

Knowing and Doing. Teachers articulated explicitly their representation of teaching and learning. T1, T2, T5, T6, and T81 reported eclectic, combined practices in which the communicative approach was the most prominent. They also adopted a humanistic approach prioritizing students’ feelings toward the class and towards them as teachers. According to T7, her sociolinguistic perspective helps her understand her students. T2 and T6 mentioned that they struggle with managing their “teacher speaking” time, classroom setup, structure, and discipline, issues already identified by Novozhenina and López-Pinzón (2018).

T4 mentioned that his concern for the students encourages him to “continuously seek ways to improve my classes and teaching practice, whether this means picking up a new book about teaching pedagogy or opening up dialogues, in person or online, with colleagues and fellow TESOL professionals about our teaching.”

Recognizing. All teachers described themselves as dedicated, passionate, friendly, and approachable. T1, T4, T5, and T6 expressed their advocacy for students’ autonomy, as facilitators, and not as the center of the knowledge experience. T4, T5, and T7 mentioned a disconnection with students, needing more patience to lower the students’ anxiety and not to rush them.

T1 said she provides students with opportunities for language learning and personal growth, and for the co-construction of a positive and safe classroom environment as a means to encourage effective language learning. T2, T3, T4, and T7 gave a similar answer.

Analyzing. Overall, teachers stated that their practice was focused on student motivation, autonomy, and needs. Good rapport, flexibility, adaptability, patience, and perseverance are the strengths that contribute to the attainment of the student-related aspects. Some teachers reported weaknesses such as prioritization of syllabus fulfillment, which undermined students’ autonomy and needs. As for rapport, there were difficulties establishing personal connections with students, in the case of T4, due to cultural factors (Chirkov, 2009), managing teacher speaking time, and discipline (Novozhenina & López-Pinzón, 2018).

Teacher Reflective Journals

Knowing and Doing. Regarding professional knowledge, the intellectual content of the discipline was clear for the teachers mentioned various approaches to classroom teaching of skills and transfer of knowledge. T5 and T6 alluded to the inductive approach and scaffolding, but most teachers demonstrated methodological and goal-oriented approaches. Concerning procedural knowledge, most teachers seemed task-oriented in the management of their classrooms, with few shifts in action. T1, T4, and T8 reported adapting, changing pace, or using different methods of student interaction depending on the context’s particularities. Regarding personal knowledge, we detected mostly goal-based discussion which seemed to reflect a more procedural and practical attitude to teaching. Teachers wrote reflections rooted upon beliefs about what had worked and what had not, resourcefully connecting to their intellectual and procedural knowledge (Farrell & Ives, 2015; Goh et al., 2005).

Activities seemed to have gone well, at least from my perspective and from students’ claims. I think they learned because they said they had, and I gave them some Kahoot quizzes, which showed learning. Again, I cannot state they learned it in class because they could also have studied the material at home or outside the class. (T8)

Some teachers are responding to needs and shifting responsibility, but most of them are not reaching a dialogic approach in their classroom, an aspect which has been widely identified in the literature (Buendía & Macías, 2019; Cárdenas et al., 2010; Cote-Parra, 2012; Cuesta-Medina et al., 2019; González et al., 2002; Insuasty & Zambrano-Castillo, 2010; Olaya-Mesa, 2018; Rodríguez-Ferreira, 2009; Viáfara & Largo, 2018). Teachers do, however, offer innovative ways to learn English through the social, political, and cultural contexts as shown before by Kumaravadivelu (1994) and Fajardo-Castañeda (2011). Teachers chose statements such as adapting to fit learning style, using phones and game playing as resources, which seems to indicate the existence of contemporary identities to help construct ludic spaces for generating an encouraging learning environment. Others contextualize and personalize content to connect it to the students’ lives.

They wrote their paragraphs and we checked one of them by highlighting the parts together. Yet this is not the way I like to have my classes; I must point out that at least they seemed to understand the topic and solve a task based on what they were supposed to learn. (T7)

As for maximizing learning, most teachers mentioned providing opportunities, feedback, and safe spaces for motivation and affectionate communication. Teacher inquiry, however, was not mentioned often in the discussion. Only T4 referred to using research or even consulting friends to help students attain or “grasp” the concepts being discussed in class, which Putnam and Borko (2016) have concluded to be forms of critical, reflective teaching practices.

Analyzing. Analyzing learners’ needs, motivation, and autonomy appears to be a challenging competence for these teachers. The skills and knowledge required for doing so effectively intersect with the demanding nature of the context. We found that the teachers’ abilities to analyze are mainly imbued with procedural skills and knowledge (Goh et al., 2005). Accordingly, the teachers mentioned that learners needed guidance, support, and directedness to focus on tasks. They also mentioned the need for encouragement towards autonomy, to relate learning contents to their lives and to enhance their language accuracy.

Then the next time I taught the class I got a particularly unresponsive group, which made me realize that I needed to make sure I had various forms of scaffolding in place to ensure all students were successful, which is ultimately what I want to see: Every student experiencing success at the level they are ready for. (T4)

An associated idea identified was the teachers’ tendency to focus on learners’ needs by observing and acting, but they never mentioned including the learners themselves, by asking them to identify their needs, or by engaging students in metacognitive practice.

I have never asked the students if they felt that listening in this way helped them later [in their] exams so maybe that is a mistake that I can remedy going forward and making sure that I do this. This is a positive aspect of this kind of reflection because it forces me to think about why and what I am doing instead of moving along in my own comfort zone. (T3)

The analysis of learner motivation is presented mainly as an all or nothing construct. The verbs the teachers chose to describe their class activities suggest this underlying belief: I asked, helped, pushed, made them participate (Farrell & Ives, 2015; Goh et al., 2005). Students were either motivated and demonstrated it by being involved in activities and showing enjoyment or not. However, teachers’ relation to learners’ motivation and needs seems to be perceived as “caused by the teacher.” Only T1 and T4 analyzed motivation in a more interactive manner as a condition resulting from the student’s investment in the class. In this regard, there is a retrospective view of motivation, not a prospective, dynamic one.

Recognizing. Concerning teachers’ ability to embrace and adapt their identity, beliefs, and values, some teachers are more aware of their teaching self, and are willing to let the realities of their classes reshape it (Fajardo-Castañeda, 2011; Williams & Power, 2010).

Some of the difficulties were engaging all the students one on one to make sure each had a bit of individual feedback. It took a long time to do this but, in the end, it helped make a successful hands-on lesson because the students had a stronger understanding of what was expected of them, and how to put together a good paragraph. (T1)

Others struggle with adapting to the realities of the classroom and seem to have strict expectations of time management, interaction with students, ways of providing feedback, and on students’ behavior and participation in class (Farrell & Ives, 2015).

Some of the difficulties during the activities are time management on my part and on the student’s part. How much time do they really need for an assignment? Should I be stricter and really push them to finish within a reasonable allotted time, or because I give them more time if necessary they are just goofing off or working slowly? (T1)

As for beliefs, T2, T7, and T8 strongly consider that the students and the system (explicitly or implicitly stated administrative and academic norms) are to blame for underachievement. They attributed their students’ low English levels to a deficient level placement, lack of interest in the class and in studying, and even laziness, as T1 mentioned; however, there is little reflection on why these situations occur and on how to fix them. We can assume, from the teachers’ statements, that there is almost conformity towards the students’ lack of performance, level placement, and the pass/fail system (as found also by Quintero-Polo & Guerrero-Nieto, 2013).

Regarding values, T3 expressed not wanting to expose students to class embarrassment, which indicates sensitivity towards students’ feelings. Another example is T4’s commitment to engage all the students in class, regardless of their language level, which, for other teachers, is an unavoidable consequence of their placement and pass/fail system.

Students’ Perspective

Student Evaluation of Teachers

Knowing and Doing. From students’ answers, we identified and categorized the following aspects in these modules: positively changed perception of students towards language learning, teachers’ interest in students’ learning, opportunities for students to learn from mistakes, and pleasant class environment. Overall, students see appropriate methodologies and teaching strategies and relate those to their learning of the language. All the teachers provide them with motivation, opportunities to learn, support with error correction, and interesting topics for their future professional life. However, noticeably, T4 was not as highly praised as the rest of the teachers, which might be explained by, in his own words, “a disconnection” with his students. T4 considers that being a foreigner and being used to teaching older adults are the reasons for this disconnection. However, this recognition also comes with a reflection for improvement, in which he says: “so this disconnection I have experienced is something I am working on.”

One student said the class positively changed their perceptions on the benefits of learning English. Five students praised their teachers’ (T1, T2, T5, T7) interest in their learning and their efforts to facilitate it and create a good class environment.

Analyzing. Salient aspects found in students’ answers were teachers’ skills to fulfill students’ needs for improving accuracy, motivation, and participation in class through fun activities and games, and including relevant, enriching topics in class. Three students referred to T2 as “the best,” because the class contributes to the students’ active learning and constant participation. They also valued their teachers’ skill to teach and correct grammar through fun activities. Two students highlighted T5 for teaching context appropriate topics and promoting their skills and a well-rounded education. However, students also expressed needs for T4’s classes to be more dynamic. Similarly, one student asked T1 more balance between home and in-class activities, and another student suggested that T3 pay more attention to the students who are not doing well.

Recognizing. From students’ answers, two teachers’ identities were prominent: teachers as a source of fun and teachers as warm human beings who connect emotionally with them. Most of the students highlighted their teachers’ ability to create fun and what they called dynamic classes. T4’s students, on the other hand, highlighted the need for these. Similarly, except for T4, the students mentioned how there is affection, respect, and kindness in T1, T2, T3, T5, and T7’s classes. As expected, this closeness, as students stated, inspires, motivates, and helps them to better understand topics and perform through their learning process (Gruber et al., 2012).

Observers’ Perspective

Observation of Teachers

Knowing and Doing. Consistently with teachers’ and students’ perspectives, we saw devotion to the students, evident in the teachers’ attempts to provide constant guidance. T1, T2, T3, T4, and T7 evidenced a personal approach in their interactions and a strong investment in creating a friendly and engaging environment for their students. T4 and T8 used humor, and provided interactive, ludic opportunities for fun and play through game-like activities, which reflect their belief in the positive impact of an emotional connection on learning (Farrell & Ives, 2015). As for maximizing learning opportunities, although we saw time and space as input for the class, there were few cases of delving into or taking critical stances on cultural or political topics, when the opportunity arose (Fajardo-Castañeda, 2011).

Analyzing. Overall, there was a marked focus on the textbook and lack of encouragement for autonomy and maximizing learning opportunities. This contradicts what T6 and T4 stated in their journals. Additionally, T6, T7, T8, and T9 did not show responsiveness to the context and to students who deviated from the expected language level of the class, which they consider an irreparable flaw of the system they do not attempt to change (Farrell & Ives, 2015; Quintero-Polo & Guerrero-Nieto, 2013). This was coherent with a students’ answer in the teacher evaluation.

Recognizing. This aspect was not observable because class observations were non-participatory, and thus, there was no interaction between the observer and the teachers.

Conclusions

We shall discuss the conclusions from the different teacher evaluation instruments developed around KARDS for each one of the three perspectives (teachers, students, observers) to propose an answer to our research question and, finally, draw some implications thereof.

The Teachers’ Perspective

By using survey questions and reflective journals with guiding questions based on the tenets of the KARDS model, and by performing content analysis under the same framework, we could observe that the teachers have strong procedural and professional knowledge and clear perspectives on who they are in their humanistic, affective dimension. They guide their practice on the belief that emotional connection with students promotes effective learning (Farrell & Ives, 2015; Gruber et al., 2012), which could be more fruitful if used to listen and tend to the students’ learning needs. Additionally, the model allowed us to unveil teachers’ beliefs on motivation and autonomy. For teachers, it seems, motivation is rooted in providing students with fun activities in class that also elicit correct answers. Similarly, teachers refer to autonomy as the class moments that students have to complete a task without surveillance. Likewise, teachers’ understanding of their own autonomy is limited to decision-making based on procedural and professional knowledge conditioned by compliance with the syllabus, as opposed to the essence of autonomy for post-method teachers, who “act autonomously within the academic and administrative constraints imposed by institutions, curricula, and textbooks” (Kumaravadivelu, 2012, p. 10). We also observed that some teachers did not encourage the students’ autonomy or critical stances when opportunities arose. We suggest that such orientation towards procedure limits the students’ agency. Using KARDS, we discovered the inadequacy of the way motivation, autonomy, and learner needs are analyzed and understood in a society that calls for change (Kumaravadivelu, 2012).

The Students’ Perspective

Students’ responses framed on the KARDS model allowed us to understand their perception of their teachers’ practice and its impact on their learning process. Additionally, we found convergence points between teachers’ and students’ perceptions. For instance, both students and teachers see motivation narrowly constructed as an externality, usually provided by games and good rapport with the teacher. Consequently, students’ standards for good teaching practices involve games and entertainment. This can divert professional development from meaningful teaching practices, and it could also become an unfair evaluation of teachers whose approach does not involve games, more so if the evaluation consists of a checklist, such as the MEN’s (n.d.) questionnaire for students to evaluate their teachers.

The Observers’ Perspective

Observing teachers through the core features of KARDS, and focusing on their practice beyond the “whats,” we found not only that the teachers have strong professional knowledge instantiated in goal-oriented actions and reflections, but also that their analyzing converges towards students’ needs and motivations from a procedural orientation. Analyzing, for these teachers, follows linear views of teaching and learning or learning caused by teaching. However, some teachers lack responsiveness to the context or to students who are below their expectations. Needs seemed derived from the predetermined syllabus in response to macro factors; paradoxically, at the micro level (i.e., the classroom), our analysis did not unveil any indication of teachers responding to the students’ particular needs and motivations. This could be problematic, as failing to do so could affect the learners’ motivation (Benesch as cited in Kumaravadivelu, 2012). Through KARDS, we could see the teachers’ lack of dialogic approach toward their classroom and little inquiry orientation towards decision making, reflected also on their lack of participation in communities of practice.

Implications

This study sought to explore the KARDS model as an evaluation tool from a classroom external perspective (teachers, students, and observer) that would help identify the specific teachers’ professional development needs for a more critical and reflective teaching, something that has already been highlighted in the Colombian context by several studies (Buendía & Macías, 2019; Cárdenas et al., 2010; Cote-Parra, 2012; Cuesta-Medina et al., 2019; Insuasty & Zambrano-Castillo, 2010; Olaya-Mesa, 2018; Rodríguez-Ferreira, 2009; Viáfara & Largo, 2018). Although the small number of participating teachers and the students’ lack of elaboration on the answers about their teachers were evident limitations, the application of the KARDS model as an evaluative tool for in-service teachers seems promising. Its comprehensive and non-prescriptive nature allowed us to identify a mismatch between the understanding students and teachers have of autonomy and motivation and the meaning these concepts should have in a society that calls for change (Kumaravadivelu, 2012). These are results and analyses that other teacher evaluations tools fail to elicit due to their prescriptive nature and their main focus on procedural and professional knowledge.

Two main sets of interrelated implications resulted from this study: those associated with the application of the KARDS model as an evaluative tool, and those related to teacher education and professional development needs that stem from its application. As for the application of this model as a teacher’s evaluation tool, its comprehensive nature poses challenges to its application and to stakeholders. First, its operationalization would require professional development to promote the necessary conditions and abilities “for teachers to know, to analyze, to recognize, to do, and to see learning, teaching, and teacher development” (Kumaravadivelu, 2012, p. 122). Thus, not only will teachers theorize from their practice and practice what they theorize, but they will also become adequate observers that could facilitate a sustainable, reliable application of KARDS as a teacher’s evaluation tool.

Additionally, teacher education and professional development should reshape the understanding of motivation and of teacher and learner autonomy to abandon the perpetuated limited and procedural concepts that focus on the teacher as the main source of both motivation and autonomy. Finally, teacher education and professional development should promote critical, creative, contextual, reflective learning spaces that can reshape the relationship between theory and practice by finding an “alternative to method rather than an alternative method” and “principled pragmatism” (Kumaravadivelu, 1994, pp. 29-30).