Introduction

Numerous studies on teacher cognition have shown that preservice teachers have diverse ideas, attitudes, and motivations regarding teaching, learning, and other aspects related to the teaching profession that significantly influence the construction and development of their teachers’ professional identity (TPI; Beijaard et al., 2004; Garner & Kaplan, 2019). Therefore, the importance of preservice teachers building their TPI is being recognized at an international level (Schaefer & Clandinin, 2019; Suelves et al., 2021). Throughout this learning-to-teach process, it is important to make them reflect and wonder about who they are and how they see themselves as teachers in the immediate future (Keary et al., 2020).

Thus, the scientific and educational grounding of this study is mainly based on the constructivist approach to teacher education because it defends the idea that learning occurs only when preservice teachers are thoroughly engaged in the process of meaning and knowledge construction (Harfitt & Chan, 2017). Moreover, there is evidence to prove that mastery experience substantially contributes to preservice teachers’ constructivist teaching beliefs (Cansiz & Cansiz, 2019). Furthermore, they develop an understanding of this approach so that they can apply it to their future practice in real educational contexts as an alternative to more traditional-oriented teaching approaches. In other words, future teacher needs to avoid reproducing the traditional teaching strategies they experienced as students in their early education (Flores, 2020).

Moreover, the reflective approach to teacher education has also been a reference for this study since it focuses on preservice teachers’ beliefs. Therefore, this approach provides the study with a solid justification because it highlights the importance of thinking about one’s teaching experiences in order to identify strengths and weaknesses and introduce variations when needed to improve the learning outcomes (Blackley et al., 2017). Thus, it is necessary to introduce activities into the preservice teacher training curriculum that enable them to reflect on diverse aspects connected to the teaching practice and the promotion of metacognition (Pérez-Garcias et al., 2020).

In line with the abovementioned, most research on teacher education has mainly focused on subject matter, teachers’ competences, and traditional and non-traditional approaches over the past decade (Cañadas, 2021; Özcan & Gerçek, 2019; Werler & Tahirsylaj, 2020). However, “scholars have begun to highlight additional important factors that shape teachers’ conceptions of and actions in teaching that should be incorporated into teacher professional learning frameworks” (Garner & Kaplan, 2019, p. 8). These other factors refer to teachers’ conceptions about themselves as teachers and their TPI since it has been proven to have an influence on their success in their careers.

Considering that, this study examines how English as a foreign language (EFL) preservice teachers understand TPI as well as their beliefs regarding which aspects determine its construction and development. Additionally, it seeks to analyse whether there are significant differences in these aspects depending on the gender of the participants, mainly for two reasons. On the one hand, this variable was included because in a preliminary qualitative study, participants suggested that gender may affect their comprehension of the teaching profession. On the other hand, because there is certain disagreement in previous studies on whether male and female teachers concur in their perceptions about the teaching profession and their vocational attitudes, and evidence is still scarce regarding the effect of gender on the construction of TPI and the progression of teachers’ careers (Egmir & Celik, 2019; Kapitanoff & Pandey, 2017). In addition, the present study focuses on preservice teachers whose first language is English and on those whose first language is other than English (mainly Spanish) because it seems they face a dualism of personalities (Treve, 2021; Vega et al., 2021). Therefore, these feelings will directly affect their beliefs regarding the teaching profession, and, consequently, their TPI construction.

EFL Teachers’ Professional Identity

The initial teacher training process is of great importance in the development of TPI (Rodrigues & Mogarro, 2019). Every future teacher should start developing their commitment and identity with the teaching profession during their initial training; however, there are some groups that could be more vulnerable than others. The construction of the professional identity of language teachers is a topic that has generated great interest in both research literature and the implementation of educational policies in recent decades (Hashemi et al., 2021; Mora et al., 2014; Trejo-Guzmán & Mora-Vázquez, 2018). In this study, the focus is on preservice teachers whose first language is not English because the “native vs. non-native English speakers” dualism could affect the development of their TPI and, consequently, their professional development (Zhu et al., 2020). In addition, there is also a significant variable that may accentuate this issue, and it has to do with the teacher training model (consecutive vs. simultaneous; Gómez et al., 2017). To be specific, consecutive training models do not allow for the opportunity to combine subject and pedagogical content simultaneously and, thus, do not include a teaching element from the beginning, and this hinders the integration of the two. Therefore, preservice teachers see themselves as professionals rather than teachers (Schaefer & Clandinin, 2019).

The globalization and internationalization of our world brought about the phenomenon of Englishization (Lanvers & Hultgren, 2018) in all fields, particularly in education. The spread of English has been significant, and it has even become the language of instruction in diverse educational levels (Feddermann et al., 2021; Macaro et al., 2018). It is undeniable that this situation has provoked great changes in language teaching and testing around the world. Thus, it has caused a global need for English language teachers, mainly in EFL countries (Llurda, 2004). Consequently, there is still a debate regarding what is better: whether to depend on professionals whose first language is English as the model in language teaching due to their culture and language proficiency, or to trust EFL teachers with their linguistic and pedagogical skills (Dervić & Bećirović, 2019). In this regard, scholars tend to favor the second option on the grounds that EFL lessons are more linguistically varied and allow teachers to switch codes when necessary. Nevertheless, the discussion is still open due to the diversity of learning contexts, but, undoubtedly, this is something that has an impact on preservice EFL teachers’ TPI (Zhu et al., 2020). Thus, beliefs about the teaching of EFL affect the development of the professional identity of EFL teachers and, given that identity is a construct with a multiple, dynamic, and changing character, teachers should be exposed to teaching experiences that contribute to building a professional identity with a sense of context awareness and with a multicultural vision (Chacón, 2010; Ortaçtepe, 2015).

The dichotomy between teachers whose first language is English and those with another first language and the theories behind it have a major discriminatory impact on their careers. Therefore, labels such as native vs. non-native should be reviewed against the negative effects of degrading categories (Shin, 2008). The latter group is aware of this debate and how employment discrimination may affect them, mainly in the private sector (Clark & Paran, 2007). Hence, it may impinge on the way they develop their TPI. In this sense, it is important to reinforce professional identity construction throughout their initial teacher education so as to prevent possible burnout rates (Lu et al., 2019), strengthen their competences (Roulston et al., 2018), and reduce their anxiety and feelings of helplessness and loneliness during preservice training and early career development (Deng et al., 2018).

Teachers’ Professional Identity Influencing Factors

TPI is not a static attribute, teachers continuously develop and change their sense of self through looking at and analyzing their daily professional practice and their lives as teachers (Vokatis & Zhang, 2016). This TPI construction process starts from the moment they made the decision to become teachers (Donnini-Rodrigues et al., 2018). Not only do they undergo variations in the development of their skills, but they also modify their conceptions of the teaching profession and its social image (Torriente & Villardón-Gallego, 2018).

Scientific literature on this issue states that TPI may be influenced by a wide range of aspects, both personal and contextual as well as internal and external (Rodrigues & Mogarro, 2019). First of all regarding the personal aspects, there are studies that point out the need for teachers to have a deep interest in their own teaching-learning process and the ability to awake this concern among their students (Leeferink et al., 2019), have an intrinsic vocation for education to avoid possible friction linked to motivation or commitment (Meijer et al., 2011), be empathic and build a positive and solid self-esteem as future teachers (Day, 2018), among others. In addition, at the individual level, other independent factors-such as gender-should be considered (Chang & Lo, 2016; Nürnberger et al., 2016). Moreover, Egmir and Celik (2019) suggested that educational beliefs and teachers’ identities during initial teacher training periods significantly differ in terms of variables such as gender, field of knowledge, and degree. Focusing on gender as one of the most debatable issue, some studies highlight that differences between women and men in the field of teaching exist and affect their attitudes along their careers (Kapitanoff & Pandey, 2017). At first, Monroy and Hernández-Pina (2014) did not find clear evidence of any effect of gender on the development of TPI. However, with the increasing interest in this issue, later research projects have noted significant differences in how men and women from different fields of knowledge construct their TPI during their initial teacher training process (e.g., Pérez-Gracia et al., 2019). Along this line, Healey and Hays (2012) had already done a study where the differences between male and female participants with respect to aspects of professional identity were evaluated. The results of the discriminant analysis indicated gender differences in the development of professional identity. An additional regression analysis revealed a significant predictive relationship between professional engagement and professional identity development and orientation. However, no recent long-term and large-scale studies on EFL teachers’ TPI were found.

Secondly, contextual factors should be considered within the training background. The placement period included in the secondary education teacher training master’s program is one of the aspects that has been more widely analyzed since preservice teachers’ participation in teaching practicum gives them both changes and challenges related to tasks such as planning or coordination with colleagues (Leeferink et al., 2019). Therefore, Yuan et al. (2019) state that “confronting a new learning environment, student teachers are likely to create new forms of identities through their cognitive learning, social interactions and emotional experiences” (p. 975). Consequently, they may start to create an identity different from the one they already have, and it will possibly influence their practice and development. These dissonances sometimes help them grew and reflect on their own professional learning. Moreover, learning by doing with mentors and peers as well as designing a professional project are decisive in TPI building (Schaefer & Clandinin, 2019). Finally, receiving specific training on pedagogy, psychology, and teaching methodologies also contributes to the way they feel dedicated to teaching (Tashma-Baum, 2014).

All in all, we believe this study is important to deeply analyze how the participants understand TPI and which aspects they believe contribute to its development. Thus, the results could bring about the opportunity to critically reflect on the ways their training could be reinforced so as to reduce the anxiety and lack of confidence caused by the native vs. non-native dichotomy (Hashemi et al., 2021). In addition, this study results in newness in diverse issues: dualities on TPI construction among English as a first language preservice teachers and non-English as a first language preservice teachers, lack of studies focused on TPI construction as well as the importance of gender in TPI construction in this collective.

The objectives of this study are:

Method

This is an empirical and descriptive study based on the quantitative analysis of data collected over several academic years within a master’s degree in secondary education teacher training.

Participants

The sample was made up of 131 preservice EFL teachers from six consecutive academic years (2014-2020), 84% were women and 16% men. The sampling technique applied was convenience sampling (Emerson, 2015). Since participants were selected based on availability and willingness to take part, they participated voluntarily in the study. The average age of the sample was 21.2. All participants were enrolled in the master’s degree in secondary education teacher training at Universidad de Córdoba (Spain). However, their home university (where they carried out their degree studies) were as follows: most of the participants were from the Universidad de Córdoba (82%), while 9% were from other universities in Andalusia, 7% were from other universities in Spain, and 2% were from universities in other countries.

In Spain-and in other European countries (Eurydice, 2018)-initial teacher education follows a consecutive training model which focuses on training in pedagogy. In the case of secondary education teachers, people first need to hold a degree in a specific area such as EFL and then, if they are interested in becoming secondary education teachers, it is compulsory for them to enroll in the master’s degree in secondary education teacher training, which also includes a placement period where preservice teachers are immersed in real education contexts.

Instrument for Data Collection

This study was carried out using a questionnaire designed on the basis of a previous qualitative study (Pérez-Gracia et al., 2021). The instrument is made up of 40 variables divided into two sections:

Section 1 gathers information about the participants regarding nine independent variables related to various socio-demographic data, namely sex, age, field of knowledge, degree studies, time since they finished their degree studies, current employment situation, teaching experience, length of teaching experience, academic year in which they are enrolled in the master’s degree.

Section 2 corresponds to a five-point Likert scale with response options varying from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). It comprises 31 items organised in four dimensions (D1, D2, D3, and D4) related to the following respective aspects: D1 = 15 items on elements that globally characterize or define the TPI; D2 = five items on the development of the TPI in different stages of education; D3 = five items on differences in the way teachers and other professionals construct their professional identity, and D4 = six items on the aspects that contribute towards the development of the TPI.

However, for this study, two dimensions have been chosen: Elements that globally characterize the TPI (D1) and aspects that contribute towards the development of TPI (D4). The decision was made to use these two dimensions due to the scope of the journal as well as because D1 and D4 respond to a more personal and reflective perspective whereas the other dimensions have to do with more professional and contextual issues (Pérez-Gracia et al., 2019).

The instrument was validated in terms of content, comprehension, and construct. Firstly, the content and comprehension validity were carried out by a panel of experts through a pilot study, so it was improved regarding readability, internal consistency, and appropriateness of the scale. Then, after applying confirmatory procedures, the panel demonstrated the instrument has a satisfactory metric quality too. The indices show that the adjustment of the proposed model is highly appropriate, as the goodness of fit index (GFI) has a value of 0.889, 0.872 for the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) and 0.773 for the parsimony goodness of fit index (PGFI). The x2 has a value of 2.401. Finally, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) shows that the model has a good fit, with an index of 0.05 (Lo = 0.046 - Hi = 0.054), and the RMR is 0.044. All in all, the instrument is solid and has a reliable psychometric quality (0.879 Cronbach’s alpha).

Research Procedure

The data employed in this study were collected at the beginning of the specific module of Complements to Disciplinary Training of the master’s degree in secondary education teacher training at the Universidad de Córdoba (Spain). We chose this module because it deals with issues regarding teachers’ professional profiles and development, which is in alignment with TPI formation. This module is taught in the first semester of the master’s studies, and data were collected during face-to-face lessons.

Prior to data collection, students were informed of the objective of the study and its importance. Then, they were also told about the ethical issues such as the anonymity, confidentiality, and privacy of their answers. Only those students who were willing to participate answered the questionnaire, which took them between fifteen and twenty minutes.

Data Analysis

Diverse statistical treatments were applied in order to achieve the objectives of the study. Firstly, based on the first objective, descriptive analyses (mean values and standard deviation) were applied in order to find out non-English as a first language EFL preservice teachers’ beliefs regarding TPI understanding as well as its influencing aspects. These analyses were done using SPSS V25.

Secondly, to be able to identify whether there were significant differences among the participants based on their gender in both dimensions of the instrument (Objective 2), we carried out the Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA).

Finally, in order to discover the variables responsible for these significant differences, SIMPER (Similarity Percentages) was applied so as to calculate the percentages of similarity/dissimilarity between the two levels of the gender factor. Thus, it allowed us to determine which items were responsible for the greatest proportion of gender differences among the variables on the questionnaire that the PERMANOVA determined as being significant. The PERMANOVA analysis was done using PRIMER V6.

Results

This section presents the results based on the objectives of the study.

Trends in EFL Preservice Teachers’ Beliefs on TPI

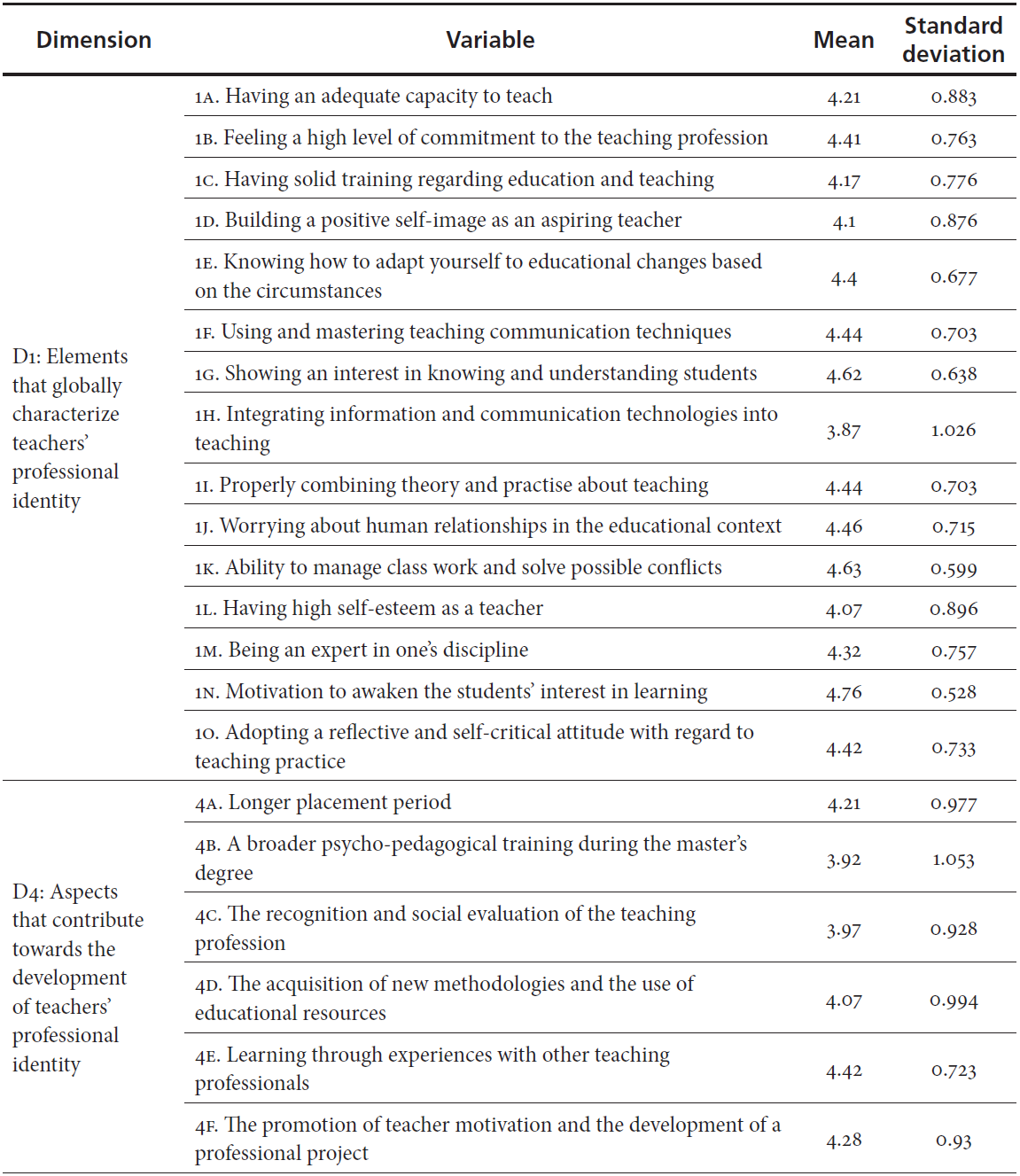

Considering the first objective, Table 1 presents the participants’ beliefs about TPI and its influencing factors.

The first dimension, which refers to the participants’ understanding of TPI, shows that there is a high level of agreement among participants since the frequency rates are higher than 3.5.

The items with the highest frequency values are related to motivating pupils during the teaching-learning process (1N, x̅= 4.76), the ability to manage class work and solve possible conflicts (1K, x̅= 4.63), showing interest in knowing and understanding students (1G, x̅= 4.62), and worrying about human relationships in the educational context (1J, x̅= 4.46). On the other hand, the items with the lowest frequency, and therefore, with the lowest rate of agreement have to do with integrating information and communication technologies (ICT) into teaching (1H, x = 3.87), having high self-esteem as a teacher (1L, x̅= 4.07), building a positive self-image as an aspiring teacher (1D, x̅= 4.1), and having a solid training regarding education and teaching (1C, x̅= 4.17).

The frequencies of the responses in Dimension 4 (aspects that contribute to the development of TPI) are slightly lower than in Dimension 1. The items with the highest frequency refer to learning through experiences with other teaching professionals (4E, x̅= 4.42), the promotion of teacher motivation and the development of a professional project (4F, x̅= 4.28), and a longer placement period (4A, x̅= 4.21). However, the sample shows that a broader psycho-pedagogical training during the master’s degree (4B, x̅= 3.92) and the recognition and social evaluation of the teaching profession (4C, x̅= 3.92) are not that important in the development of the participants’ TPI, and there is a lower rate of agreement in this regard among preservice teachers.

Differences in Terms of Gender

Table 2 shows the results of the PERMANOVA analysis intended to identify the possible significant differences between the participating men and women regarding TPI understanding and influencing factors.

Table 2 Results of PERMANOVA According to Gender

| Variable | Gl | Sc | F | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 1 | 188.91 | 3.438 | 0.004 |

| Residues | 129 | 7088.5 | - | - |

| Total | 130 | 7277.4 |

Note. Own elaboration.

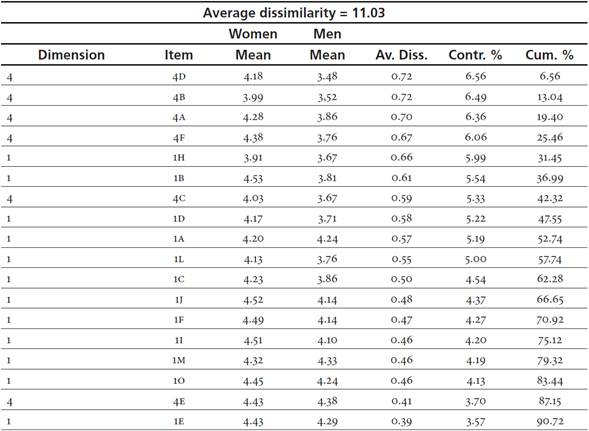

PERMANOVA results (Table 2) show that the independent variable sex significantly affects the way participants respond to the items on the scale in both dimensions (men and women respond differently; F = 0.438; p = 0.004). Finally, Table 3 shows the items responsible for these gender differences.

The results of the SIMPER analysis (Table 3) show an average dissimilarity of 11.03 between men and women. This difference is mainly owing to the following items:

4D: The acquisition of new methodologies and the use of educational resources (6.56%)

4B: A broader psycho-pedagogical training during the master’s degree (6.49%)

4A: A longer placement period (6.36%)

4F: The promotion of teacher motivation and the development of a professional project (6.06%)

1H: Integrating ICT into teaching (5.99%)

1B: Feeling a high level of commitment to the teaching profession (5.54%)

4C: The recognition and social evaluation of the teaching profession (5.33%)

1D: Building a positive self-image as an aspiring teacher (5.22%)

1A: Having an adequate capacity to teach (5.19%)

Women showed higher frequency levels than men in all of these items with the exception of 1A where the frequency was reversed. Moreover, most of the items responsible for the differences in terms of sex belong to the dimension about the aspects that contribute to the construction of TPI.

Discussion and Conclusions

Considering the relevance of how language teachers shape their TPI (Trejo-Guzmán & Mora-Vázquez, 2018), this research aims to make a contribution to educational research on initial teacher training from a gender perspective that contemplates various aspects of the way in which non-English as a first language EFL preservice teachers build their TPI. Specifically, it examines how non-English as a first language EFL preservice teachers understand the concept of TPI and which aspects they think may modify it. Additionally, it shows that there are differences in the participants’ beliefs in terms of gender. Hence, this study is a new contribution to TPI field of research since there are no previous studies in which an independent variable such as gender has been analyzed as responsible for differences in non-English as a first language EFL future teachers’ beliefs. Most of the studies focused on TPI have considered external variables such as participants’ previous experience and training or their field of knowledge and devoted less attention to internal and personal variables such as gender or age.

This group of future teachers who have followed a consecutive training model is sensitive for diverse reasons, but mainly, due to the controversy that still exists in non-EFL countries regarding the aptitude of EFL teachers (native vs. non-native). Therefore, not only it is decisive to know in depth how they perceive the meaning and influence of TPI during their initial training so as to strengthen their social image, self-esteem, and commitment to the profession in their near future (Yuan et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2020), but it is also necessary to study how the native vs. non-native dichotomy affects their TPI development in more detail while paying specific attention to those future teachers whose first language is not English. Thus, future research may explore and analyze this issue considering its impact on teachers’ professional development.

To start with the first research objective, this study shows that preservice teachers already have their own conceptions and beliefs regarding TPI, although their previous experience in education is limited. There is a broad degree of agreement among participants since they broadly relate the understanding of TPI to being motivated to awaken students’ interest in learning, having the ability to manage their classrooms and solve interpersonal conflicts, and being concerned about interpersonal relationships in educational contexts. These results coincide with previous studies (Leeferink et al., 2019; Meijer et al., 2011) that point out the connection between TPI and the attitude with which preservice and in-service teachers face their training and professional development. However, the participants did not agree to a great extent that the use of ICT or receiving good training in education and teaching has anything to do with their identity as teachers. Nor did they concur that building a positive image as an aspiring teacher and developing a high self-esteem had anything to do with TPI. These last results are not in line with Day (2018) and Torriente and Villardón-Gallego (2018), who clearly identified emotional wellbeing and resilience as framing TPI and teacher social prestige as a determining factor in identity and quality of education. This leads us to think that research on TPI should be focused and approached by areas of specialization since its construction changes depending on the group.

As for Dimension 1, participants did not show values of agreement as high as in Dimension 4. However, they were consistent in believing that learning through experiences with other teaching professionals (their future colleagues), developing a professional project, and the placement period were the most decisive factors in TPI construction. These outcomes agree with other studies such as the ones carried out by Yuan et al. (2019), Schaefer and Clandinin (2019), and Deng et al. (2018), who emphasized the importance of practicum to solve the numerous dilemmas and internal conflicts that preservice teachers have regarding classroom authority vs. the ethic of caring, feeling part of an institution vs. feeling like a stranger, seeing themselves as teachers or other professionals, and dichotomies regarding teaching approaches. In this sense, the literature confirms that the first experience student teachers have in real educational contexts is conclusive in making them feel committed and engaged with their professional career. In contrast the participants in this study did not clearly associate broader psycho-pedagogical training and the social status of the teaching professions with TPI influencing factors. These ideas dissent with other studies-such as the one by Day (2018)-since the scholars noted that preventing training needs and teaching social status directly contribute to the development of their identity as soon-to-be-teachers.

The second and third objectives could be discussed together. This study shows that there are significant differences between how non-English as a first language EFL preservice teachers respond to the questionnaire in term of their gender, that is, men and women answered differently as has already been highlighted in previous studies but in different fields of knowledge, not in EFL. This coincides with a previous study done on future science and technology teachers in which gender was also determinant (Pérez-Gracia et al., 2019) and with Egmir and Celik (2019), who proved that preservice teachers’ educational beliefs and identities significantly diverge in terms of gender. Moreover, this study also agrees with the perspectives and insights of Kapitanoff and Pandey (2017), who put emphasis on the existence of social stereotypes that indicate a progressive process of feminization of the teaching profession. However, these previous studies do not provide detailed information on the aspects of TPI construction about which men and women think differently. Therefore, the present study goes further in this regard, and it also contributes to the lack of evidence indicated by Monroy and Hernández-Pina (2014).

The level of agreement is higher for women than for men in most of the variables. The items in which men and women differ more are mainly related to the aspects that contribute to TPI construction and development whereas there is higher consistency with respect to Dimension 1.

Differences are more pronounced in issues related to the use of educational resources, psycho-pedagogical training, the need for a longer placement period, and the promotion of teacher motivation and development of a professional project. It seems that the participants are not quite sure that these aspects are related to TPI since they have low frequency values in the descriptive analyses too.

All in all, one of the most relevant facts is that future non-English as a first language EFL teachers showed an interest in the development of a professional teaching identity from the very beginning of their training and that their belief of TPI is closely linked to the interest in acquiring professional skills appropriate to improve the teaching and learning processes throughout the placement period (Yuan et al., 2019). Therefore, from these results we can infer the need to rethink the curriculum of this master’s degree and strengthen the work towards an adequate construction of TPI to improve future teachers’ confidence and commitment. Moreover, identity and language build each other through a complex process, where identity is founded as a changing, multifaceted, and dynamic construct that arises from the interaction of the individual with their environment. This fact also has pedagogical implications for initial teacher training programs in our current context (Chacón, 2010). In this respect, the results of various investigations of TPI in early career EFL teachers show that academic transitions, the link with the English language, teacher training programs as well as the professional culture in the work environment have a major impact on the formation of their professional identity (Trejo-Guzmán & Mora-Vázquez, 2018). However, what is unique about this study is that it includes one more aspect to consider when designing curriculum and training programmes for EFL future teacher, namely, gender. It cannot be part of the hidden curriculum but the results of the present research point to the need to reinforce different formative aspects in men and women during their periods as student teachers since it seems they may interpret TPI and the importance of its development in different ways. Finally, incorporating reflection activities in various parts of the specific master’s degree module to reinforce their confidence and self-esteem could be determinant too.

Note that the data is the result of the participants’ self-perceptions, which may be a limitation due to subjectivity. Therefore, there could be varied beliefs about the same fact depending on the context where the instrument is applied. However, it could also be seen as a positive point since it gives us first-hand information on how the participants understand TPI and its construction process (Gutiérrez-Castillo & Cabrero-Almenara, 2016).