Introduction

Becoming an English teacher in Colombia involves enrolling in an academic program, learning the target language, understanding and applying teaching methodologies, and getting involved in research processes (Viáfara, 2011). However, becoming an English teacher also implies a series of transformations that affect the very context where the process occurs. Additionally, the positions, beliefs, and emotions of preservice English language teachers (PELT) also play an essential role. Therefore, to allow the PELTs’ voices regarding their training process to be fully heard, it is necessary to open spaces for reflection and establish a relationship of dialogue with the context in which they are involved. In this way, PELTs may be able to build their understanding of what it has meant for them to be participants in a community of practice made up of members of the undergraduate program to which they belong (Castañeda-Trujillo, 2020).

In this sense, it is necessary to see research as a two-way process: when the researcher investigates himself/herself and when they establish a co-interpretation with another researcher. Consequently, these research spaces for reflection, such as the one carried out here, help to unveil what is not perceptible from an external position to the undergraduate program. Furthermore, these research experiences provide conditions for empowerment and critical emancipation while inquiring about oneself and others (Kincheloe et al., 2018).

Thus, the research presented here regards researchers as participants, turning them into agents capable of building knowledge and making contributions towards constructing the PELT identity in Colombia (Castañeda-Trujillo, 2018). We decided to do a collaborative autoethnography based on two of the authors’ experiences, who happen to be PELTs in their last year of university studies, and a third author, their mentor teacher, who guided the reflection processes as well as the methodology and theory related to the study. This paper addresses teaching and learning methodologies, mentor teachers, native speakers, speakerism, colonial ideologies, and decolonization.

Theoretical Framework

English Language Teacher Education in Colombia

Teaching English in Colombia has increasingly become a way forward during the last two decades. Due to globalization, bilingual education programs require this type of education by viewing English as an economic asset and an essential requirement for modern life, for students, professionals, and the general population (Valencia-Giraldo, 2006). Thus, Colombia is actively advancing to apply an education supplemented by a foreign language (English) for future development towards a more tolerant society (de Mejía, 2006).

We can thus say that professional development in English implies all types of professional learning assumed by in-service English language teachers apart from formal teacher preparation (Buendía & Macías, 2019). This fact has become a remarkable aspect to support the demanding necessity of instructing different audiences. In Colombia, university teacher education programs usually prepare English teachers and offer alternatives for their professional growth (Buendía & Macías, 2019). Such change aligns with the Ministry of Education (MEN) bilingual education as one of its 2025 goals. These include positioning Colombia as the most educated country in Latin America in 2025 (MEN, n.d.). However, this expected education goal is disconnected from teachers’ reality in both practical and conceptual terms (Buendía & Macías, 2019), limiting their alternatives to receiving early and meaningful tutoring and coaching. Consequently, issues with tutoring and coaching “fail to give teachers the time and support they need to learn” (Sweeney, 2005, p. 4), which is considered necessary in the process of teaching practice.

Preservice English Language Teachers in Colombia

Research on PELTs in Colombia has increased recently. Although most studies focus on teacher educators rather than on PELTs, we can consider research involving PELTs as main participants regarding different topics.

We identified four main topics around PELT research in Colombia:

Cultural content and intercultural communicative competence in English teaching in university courses (Olaya & Gómez, 2013).

The development of investigative skills in Colombia’s undergraduate foreign language students such as teachers’ strategies for reading purposes or even in-training teachers’ beliefs about their teaching practice (McNulty-Ferri & Usma-Wilches, 2005).

The relevance of the first pedagogical experience and the fundamental role mentor teachers play in shaping PELTs’ future teaching practices (Aguirre-Sánchez, 2014; Lucero & Roncancio-Castellanos, 2019).

PELTs’ essential role in English teachers’ education and the practicum as a space where PELTs feel empowered and resist colonial epistemologies of English language teaching (ELT; Castañeda-Trujillo, 2018).

Although Olaya and Gómez (2013), McNulty-Ferri and Usma-Wilches (2005), Aguirre-Sánchez (2014), and Lucero and Roncancio-Castellanos (2019)) focus on what is essential and relevant to learn more about PELT training process, they fall short of explaining the actions taken by PELTs during their teaching practice. Conversely, Castañeda-Trujillo (2018) analyses PELTs’ pedagogical practicum and their role in real contexts, which is closely connected to our research aim.

When we consider the pedagogical practicum, we visualize it as the primary encounter in which PELTs lay the foundations upon which they construct themselves as English language teachers (Lucero & Roncancio-Castellanos, 2019). During the practicum, they experience, essentially for the first time, what it is like to be immersed in a classroom; a process that is “full of feelings and emotions” (Lucero & Roncancio-Castellanos, 2019, p. 173). The advice of mentor teachers is also fundamental at this point, as PELTs can have access to an expert’s opinion, which may assist them in reformulating their own practicum.

Ideologies in English Language Teacher Education

Teaching as a profession. Many authors agree that part of the English language teacher education agenda relies upon professionalization and social control (Cochran-Smith & Fries, 2001; Popkewitz, 1985). Professionalization implies preparing English as a second language and sheltered English teachers by teaching them language acquisition theory, language teaching methodologies and approaches, and a range of content/subject matter (Bartolomé, 2010). Thus, social power affects how the dominant social ideologies shape the curriculum and impose power, culture, and language disposition over the teacher and the students (Cochran-Smith & Fries, 2001; Giroux, 1985).

Therefore, a professionalized language teaching education relies on methods, theoretical principles, and classroom procedures. Kumaravadivelu (2008) examines these parameters and tries to bring a critical vision of L2 learning and teaching alongside the connection with professionalized teaching education. The primary purpose is to transition from traditional and standard methods to post-methodological processes where the best method is not “out there ready and waiting to be discovered” (Kumaravadivelu, 2002, p. 7) and where theory, research, and practice are fundamental to enhance the professionalized stage of language teaching education.

English and Englishes. According to Garside (2019), over the past 200 hundred years or so, English has become the lingua franca (shared language) in a vast range of industries and areas, so it is now recognized as the standard language for international communication. Thus, English is no longer exclusively used by native speakers: “There are currently as many people learning English as there are native speakers of this language in the world” (Garside, 2019, p. 1).

There is a relative value of the different varieties of English used by native and non-native speakers. Those English varieties are known as “Englishes” and are part of the world of Englishes or the worldwide practices that acknowledge English varieties bestowed on the nations within which they are spoken (Mahboob & Szenes, 2010). Such Englishes have discrete linguistic features to contrast one variety with another and give a sense of the transformation of the English language from one place to another as part of its use as lingua franca. The problem, however, is not the varieties (Englishes) of English per se, but which varieties are selected and taught, a decision that basically rests upon what different educational authorities (government, school managers, etc.) perceive as “a culturally ‘normal’ demographic” (Garside, 2019), and which is often based on the idea of native-speakerism.

In Colombia, the handbook Basic Standards of Competences in Foreign Languages: English (MEN, 2006) treats the English language as neutral, prescriptive, denotative, and uniform (Guerrero-Nieto & Quintero-Polo, 2009). Therefore, viewing the language as standardized and with a set of rules, and also with a denotative function (specific activities that are expected to be carried out in an English class), prevents students from coming into contact with other varieties of the language, thus “fulfilling the purists’ dream of keeping the language as unaltered as possible” (Guerrero-Nieto & Quintero-Polo, 2009, p. 142). Moreover, there is a preservation of the idea of using just two accepted varieties of English to be taught and learned: standard British English and Midwestern American English (Garside, 2019). In the end, a language becomes merely an instrumental tool that limits teachers from accessing the richness of the language itself.

Native-speakerism. Part of our identity as teachers of English refers to the definition of oneself as a teacher on our professional development. One example is the concept of Native-speakerism, which, as Holliday (2005) argues, “is a pervasive ideology within ELT, characterized by the belief that ‘native-speaker’ teachers represent a ‘Western culture’ from which spring the ideals both of the English language and of English language teaching methodology” (p. 385). Consequently, native-speakerism can be understood as an ideology that privileges Western ELT institutions’ voices by reinforcing stereotypes to classify people, especially language teachers, as superior or inferior depending on whether they belong to the native speaker group or not.

Many authors (Bonfiglio, 2010; Davies, 2012; Faez, 2011; Holliday, 2013, 2015) recognize “speakerhood” as similar to race; both concepts are not biological, but rather a socially constructed imaginary concept in ELT. According to Singh (1998), speakerhood is interpreted from social and discourse factors such as ethnic background, accent, name, and disposition to self-identify as a native speaker. The concept is often a very subjective and political matter. Native-speakerism needs to be discussed at the level of the prejudices installed in the teacher’s practice and the dominant professional discourses to promote new relationships and understand the material consequences of this symbolic relationship.

The impact of native-speakerism is evident in many aspects of professional life, from policies to language presentation. According to essentialist cultural stereotypes, Holliday (2005) claims that an underlying theme is the “othering of students and colleagues outside of the English-speaking West. The influence native-speakerism exerts on the careers of ‘native’ and ‘non-native speakers’ is a complex one and very much depends on the context” (p. 25). Rivers (2013) proposes that both groups can suffer adverse effects; however, native-speakerism does not equally affect the two groups and does not always have to be negative.

Lowe and Pinner (2016) describe two experiences related to teachers’ self-confidence and authority. The first is a lack of trust from students and colleagues due to not being a “native speaker” and not having an authentic voice in the language. The second one is not being perceived as an authoritative voice and losing recognition and value as professionals. It demonstrates some of the effects of native-speakerism in teachers’ lives, depending on the category into which they are placed, and how it disturbs their personal and professional identities and circumstances.

English Language Teacher’s Identity

After conducting a literature review, we found two factors in establishing teachers’ professional identities. The first type includes individual characteristics such as their personal experiences as students and PELTs. A second type is connected to external discourses associated with teaching and learning. These discourses come from the theory, education policies, different contexts, and models of practice.

The first type presents many studies approaching individual identity related to professional identity. Authors such as O’Connor (2008), Shapiro (2010), and Vavrus (2009) highlight the importance of personal factors in constructing professional identity. These studies focus on the connection between personal identity, emotions, and the importance of self-image in building teachers’ professional identity. Olsen (2008) considers that personal history is paramount to professional identity development, integrating teachers’ induction period experiences, particularly ideas from personal or professional understandings. Olsen’s concept of identity describes it as emerging from teachers’ experiences. From this perspective, teachers are always engaged in different interactions with others while recreating themselves as professionals:

The collection of influences and effects from immediate contexts, prior constructs of self, social positioning, and meaning systems (each itself a fluid influence and all together an ever-changing construct) that become intertwined inside the flow of activity as a teacher simultaneously reacts to and negotiates given contexts and human relationships at given moments. (p. 139)

Olsen (2008) seeks to reconceptualize teacher learning as a constant, positioned, holistic, and identity-related process designed to integrate past and present experiences. The author also presents the negotiation between different teaching discourses that emerge from teachers’ experiences as students and educators, imaginaries of teaching, and professional practice.

The second group of scholars looks at the connection between social aspects and professional identity. This group can be subdivided into those focusing on studies regarding the importance of learning contexts for professional identity development and those discussing identity concerning socio-political contexts, mainly connected with education policies and professional development.

Social identity theory promotes a definition of identity or self-definition based on social categories, such as nationality, race, class, and so on, that deal with power and status issues. Individuals develop their identities depending on the social types they belong to. This self-definition is a dynamic process in continual change and is determined by time and context (Sherman et al., 1999); furthermore, identifying with a negatively valued group will have a negative impact on teachers’ self-esteem.

Method

This study’s objective is to express the insights of two preservice teachers about the teaching profession after they have experienced the practicum from their perspective as participants and researchers. To do so, we decided to use collaborative autoethnography (CAE) as our research method (Ngunjiri et al., 2010). CAE places self-investigation at the center stage and allows us as researchers to work collectively and cooperatively to question our experiences. The CAE methodology assumes that, as participants, we are active agents of change. It positions us within the other’s experiences and reveals various aspects of forming our identity as processors within the bachelor’s degree in ELT (Ellis & Bochner, 2006; Ellis et al., 2011; Yazan, 2018).

As researchers and participants, we shared the same context, in this case, a public university in Bogotá where we are finishing our bachelor’s degree in ELT. Throughout the bachelor’s degree program, we have had the opportunity to take seminars related to linguistics, the teaching and learning of languages, and other seminars complementary to our training. Additionally, we took four semesters of pedagogical practice, two in primary school and two in secondary school. That enabled us to carry out this research, and together with our advisor, we prepared everything to start the process of data collection and analysis using the CAE methodology.

For data collection, we followed the suggestions provided by Chang et al. (2013) to obtain a more detailed description of our socio-cultural context and improve our stories’ credibility. First, we used personal memories and personal reflections on this study’s central theme and wrote them in a journal. Second, we created spaces for discussion about our experiences. These spaces allowed us to obtain other data types that came from sharing and to delve into what was collected in the journals. Subsequently, we iteratively reviewed the two instruments (the journal and the discussion transcripts) to find the similarities and differences in our experiences. With the data resulting from this iterative process and established from the theoretical framework, we triangulated and extracted common categories for us as participants and researchers. These findings are explained in the next section.

Findings

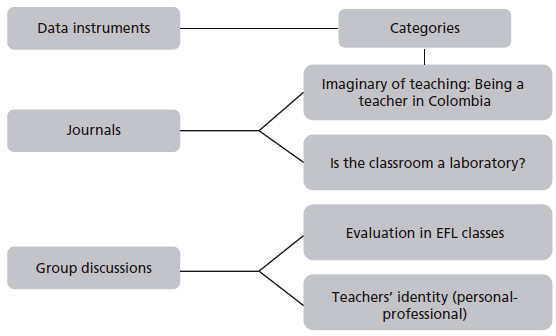

During the data analysis, we found four main categories we considered significant as part of our PELTs experience in the bachelor’s degree in ELT (see Figure 1).

Imaginary of Teaching: Being a Teacher in Colombia

Our vision of what it is like to be a teacher in Colombia is reflected in how we express the feeling of becoming a teacher. Although our backgrounds are different, we encountered similar social imaginaries of teaching that did or did not affect our decision to study for a bachelor’s degree. From those perspectives, we realized that we would not earn much money by applying for a bachelor’s degree, and that it was challenging to be a teacher. Moreover, it was not worth studying a demanding profession to receive little money. Those beliefs made us wonder if we were making the right decision by following this path. Why does society always think this bachelor’s degree is less worthy than others? Why do we qualify the value of something by the income we might receive?

All professions are demanding; they require innumerable skills, abilities, and substantial effort. However, teaching does not receive the recognition it deserves, and it is not the teachers’ fault that the educational system underestimates those who educate society. Judging by the admission processes, the value of teaching seems to be discredited and underrated, as the dean of the Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia in 2018, Diana Elvira Soto, affirms:

This is a severe problem in social imaginaries. It would seem that those of us who have entered programs to study for a bachelor’s degree are mentally retarded because we are assigned the lowest score for admission. Hence, premises such as “anyone can be a teacher,” “study this career and then move on to the one you like,” “even as a teacher, what matters is work.” This makes teachers’ profiles significantly varied since many enter the career without knowing the educator’s function. (¿Vale la pena ser profesor en Colombia?, 2018, para. 3; translated from Spanish by the authors)

The previous excerpt is a good example of the general perception most people in our country have towards the teaching profession. It is seen by many as an unviable career with undemanding admission criteria, which generates the feeling that “anyone can be a teacher.” Moreover, the government does not invest money in teaching careers, certification, training, and staff, although they require teachers in Colombia to be certified if they want to teach, which puts the economic burden on teachers themselves:

Tests and trainings represent a hefty load for Colombian teachers, especially for those at the beginning of their career, because of their high costs. . . . A person on the Colombian minimum wage would require a full month of work to pay for the IELTS test and two months to pay for the course. (Le Gal, 2018, p. 5)

In the end, this leads to inadequate teacher training, few opportunities for teachers to improve professionally, and inequitable wages. Furthermore, schools are not usually willing to provide spaces for teaching practice, and they demand experience and other requirements that are not easy to attain.

As a result of the reflection carried out, we converged around our experience as PELTs at the beginning of our bachelor’s degree. Camila was influenced by a family of teachers who already knew what being a teacher means. Camila was thinking deeply about it. Sometimes she heard people saying that the pay was not enough and that it was better to apply for another degree, which made her doubt her decision. In the case of Cristian, even though he did not have external influences regarding teaching, he had never thought of becoming one. He enrolled in the bachelor’s program due to his interest in the English language. He always thought being a teacher was challenging and somewhat humiliating because of everything he had to go through to be respected by others. Similar to what has been described in the excerpt above, he conceived of teaching as an undemanding career and, therefore, easy to study. He just wanted to have something to do, and because he liked languages, it was an opportunity to learn them. He never had in mind what a teacher was and what the implications of the bachelor’s degree were.

Is the Classroom a Laboratory?

We will discuss this category from the two contexts where the practicum took place: primary and secondary school

Our Practicum at Primary School

There are some struggles in facing the realities of the classroom where we are trying to discover the best way to teach. However, in our pedagogical practicum experience at primary school, there seemed to be a sort of testing yet expected process that is not open to other possibilities of teaching beyond the pre-established methodology based on the traditional stages of presentation, practice, and production. As long as we closely followed such a method, planned our lessons, and created teaching material accordingly, we would comply with what was expected of us. As soon as we started the practice, we were already inhibited from doing what we consider would be more suitable for our students’ learning. We had to follow the Ministry’s curricular guidelines, the school syllabus, and what the mentor teacher set as the practicum objectives. Planning changes were minimal, and this made us feel that we could not do the things we consider best for our teaching. We sometimes felt that our opinion, or that of our students, was unworthy.

Mentor teachers like the one in our primary school pedagogical practicum always highlighted the importance of innovating; however, this idea disappeared over time, and we ended up repeating the same patterns that we intended to break. All ideas to transform pedagogy were trampled because the system followed the same traditional pattern. Moreover, in the school where our teaching practice took place, we faced the school’s unwillingness to invest in innovative pedagogical spaces: There were technological resources that they did not allow us to use for fear of their being damaged, topics we considered important to address (such as cultural awareness) were rejected as being unsuitable for young people, among other things that we believed placed the English class as a space for teaching grammar without context.

We understand that this is not totally the teachers’ fault because there are many factors that have a bearing on the situation, such as the country’s educational system, teaching experience, sociocultural factors, and so on, which affect a school’s decisions as well as the way in which teachers do their practice. However, we believe that with the support of experienced mentor teachers, spaces of an experiential type of education can be created with certain freedoms for preservice and in-service teachers to test and try new ways of teaching and learning.

If a classroom is considered a place for testing how to learn and how to teach, we could probably use that as an advantage to see what works best, what students would like, and what teachers would like. These processes should be monitored and recorded by the guidance teacher to avoid mistakes and guide the learning experience. Besides, one possible way for future teachers to better know their teaching style is by letting them try what they have in mind for the process of teaching. Nonetheless, as Wheeler (2016) says, “innovative teaching is where good teachers are inventive and creative-where they continue to discover and devise new methods and content to ensure that students always get the best learning experiences” (para. 5).

Our Practicum at Secondary School

It is not all about difficulties, however. As we have mentioned, teachers are not the ones to condemn. Some are really trying to transform their way of teaching with their practices. We recall our pedagogical practicum at secondary school since day one. After a bad experience in primary with our previous mentor teacher for nearly a year, we were not expecting much from what was coming, but we knew that things might be slightly different now that we had a different mentor teacher. What we did not expect was to have the freedom to manage our classes (following the MEN’s curricular guidelines). We were amazed to hear from the teacher that we were in full charge of our class. We selected the most suitable methodologies, approaches, and topics considering our students’ needs, the context, and the theoretical and academic resources suggested by our mentor teacher.

For example, Cristian can remember that one of his lesson plans was about sexual and reproductive rights. At first, he thought it would be difficult to put it into practice since he was dealing with tenth graders, and sometimes they take these types of issues as a joke. Cristian also felt that the headteacher (the teacher usually in charge of the class) might not like what he had planned. However, the lesson was a success and the students actively participated in recognizing the rights of their sexuality as young women and men. The lesson touched on usually controversial topics such as sexually transmitted diseases and ways to prevent them, the LGBTQ+ community, abortion, and Colombian sexual laws. The students even found out that one of their classmates was about to become a father and, although this young student may not be prepared to do so, his peers showed him empathy and acceptance. Such experiences made students participate more and argue that the school had never taught them about these topics, and in the end, they thanked Cristian for that session; even the headteacher liked what he did.

The example given is the most powerful free action taken by PELTs that gave them the sensation of being in control of their class. When you encounter significant experiences like these in your first years of teaching, you fall in love with teaching. You cannot merely apply things in which you are interested, you can also approach students’ needs even if they did not know those were essential. Besides contextualizing them regarding topics such as sexuality and sex within their immediate local environment, we as teachers can change how education is approached. Why? It seems to us that such topics are still taboo in an English class and, sometimes, the same educational institutions consider them inappropriate. However, recognizing for example that sex is normal, that there exist sexual and reproductive rights for each human being, and that students have questions to ask about that, is part of the pedagogy.

In the case of Camila, her secondary school pedagogical practicum followed a pedagogy based on workshops to develop particular skills. The workshops were created and directed by the students themselves and it was the children who decided which to register for depending on their interests. This time, the pedagogical proposal was based on writing and reading comprehension.

Here there are two crucial elements to highlight. The first was the organization of the workshops. They fostered a new pedagogical proposal based on diverse artistic and thematic elements that fit the educational context. Both students and we ourselves, as participants, contributed to the development of the workshops considering our skills, interest, and ideas about teaching and learning. The population consisted of children between the first and fifth grades, which allowed us to make a more varied intervention.

Second, as PELTs, we were not seen as mere apprentices and our opinions, unlike our experience in the primary school practicum, were taken into account during planning of the workshops. With all the freedom and trust given to us, we could become aware of our abilities and mistakes. Abilities considered the strengths and ways that we have had to develop the classes and been successful in doing so. Mistakes focused on those actions in which we felt we had failed while implementing our material and our lesson plans. The guidance we received focused on the workshops’ pedagogical aims, but this never interfered with their application. For us, the most important parts of the pedagogical intervention were the personal reflections regarding improvement of the proposals, our performance, and the results of the teaching activities developed by us.

On the other hand, the workshops transformed the students’ vision of normal assessment and they, with the preservice teacher, worked together to construct knowledge. The students’ relationship with us was horizontal, so that many of the contents and activities had their input and suggestions. The students could decide not only about which workshops were of interest but also how to carry them out. We decided not to assign grades in an effort to increase students’ intrinsic motivation. This enabled students to get involved and innovate in their class projects, making them produce new understanding or knowledge to work on their tasks.

This teaching and pedagogical practice perspective represented enormous growth in our PELTs’ identity and perspective regarding the possibilities and challenges for education and how to face and redefine them from our profession.

Evaluation in EFL Classes

According to Walsh (2020), evaluation can serve as a decolonization element. Teachers and students follow a universal, standardized, and commodified assessment system that contributes to colonization by the European and North American cultures. The concept of global evaluation classifies knowledge and decides what is valid and what is not; this idea denies the value of many ancestral, empirical, and traditional understandings that disappear over time. This random idea that the better the score, the better the knowledge you have, is not valid in the end. Students’ competencies and abilities are not and should not be based on numerical parameters that classify who is at the top and who is at the bottom. We do not stand in the way of a commodity that denigrates and leaves other skills aside (artistic, for instance). We know what it is like because we have always faced it at school, at university, and in our personal and professional lives.

As far as we know and consider, we can provide other evaluation methods by using student-centered learning strategies, turning them into assessments where we not only advocate for the recognition of students’ abilities but also where intercultural spaces are projected in the proposed activities and that qualifying evaluative standardizations are ended where inequality, inferiorization, racialization, and discrimination persist (Walsh, 2010). While assessing our students’ performance, we cope with their needs by gathering from different information sources that show the voices, needs, and ways of building and transmitting the knowledge that the student possesses. In the end, assessment can serve as an activity where all kinds of relationships are woven, and knowledge is built. Thus, it could help us see students’ results in terms of their pedagogical experience and what we need to do to reinforce it. For instance, using tasks to assess, or playing roles, or even crafting, can denote a process of learning and assessing it, not just assigning a score to comply with the requirements, but to really assess the students’ performance of tasks.

Teachers’ Identity (Personal-Professional)

We could say that positive experiences are those that strengthen our continuous construction of professional identity. However, not everything we consider positive is what makes us better regarding that identity. Ibarra and Schein (as cited in Slay & Smith, 2011), define professional identity “as one’s professional self-concept based on attributes, beliefs, values, motives and experiences” (pp. 87). These features are linked to everything that surrounds the individual and his or her relationship with the means of action in which he or she operates, which makes them feel, experience, think, and live in different ways. Thanks to this, it is possible to learn and relearn how to teach and discern about teaching, strengthening one’s capacities and skills, and the professional aspects that transform the individual’s conceptions of the world while he or she gathers new experiences, knowledge, failures, disappointments, joys, and much more. In our case, that chance of changing our conceptions of the world is possible when we belong-or feel we belong-to different communities of practice, such as the schools where we carried out our pedagogical practicum, our fellow PELTs with whom we shared our pedagogical practicum experiences, the research group of which we are members at the university, and so on. Thus, in these communities, knowledge is obtained, and this allows us to interpret the world and make sense of it (Lave & Wenger, 1991), and while we are trying to figure that out, we start shaping those features that strengthen parts of our identity.

As part of our reflections, we discussed the influence of many factors of being part of such communities of practice. We understood that teaching is learned day by day, that the being is formed as the result of what is lived, that there are no perfect teachers and there are no ideal methodologies, so that a teacher capable of teaching is carved out. The teacher is not always an expert in the sense that he or she does not know everything, but the willingness to teach with passion and effort allows him or her to adapt and seek the best of the environment to transmit meaningful, didactic, functional, and above all, humanistic practices.

The teaching identity also refers to how teachers subjectively live their work, keeping in mind the aspects that satisfy them and those that do not. Identity does not arise automatically; it occurs through a complex, dynamic, and sustained process in time (Beauchamp & Thomas, 2011; Beijaard et al., 2004) and is continually prolonged and varied throughout the teacher’s career. Moreover, it is affected by personal and professional aspects that shape such identity or identity varieties, built up thanks to contact with the environment. This allows PELTs to recognize and be recognized in a relationship of identification and differentiation concerning other PELTs.

As Colombian PELTs, we learn English from a nativist perspective, and we have assimilated these patterns through our professional and academic development. This is analyzed by González (2007), who affirms that Colombian teachers’ professional development “advocates the superiority of the native speaker and favors British English (a prestigious variety of the inner circle) over other varieties of language” (p. 327) since it adheres to “power and colonial discourses that perpetuate the dominant status of the culture and speakers of English” (González, 2010, as cited in Le Gal, 2018, p. 5).The concept of “the ideal English speaker” has settled a standard that all professionals must meet; the idea of native speakers as the most qualified to teach the language favoring the status and knowledge of the native speaker over Colombian teachers who cannot be categorized into what a native model features (Espinosa-Vargas, 2019; Guerrero, 2008), which is a way of exclusion and repression for future English language teachers.

The native speaker association with proper language and proficiency to teach positions non-native teachers as “inauthentic.” This positioning characterized as inauthentic has consequences for teachers’ identity; for example, teachers are judged continuously and compared unfavorably with native-like speakers, who gain more attention and relevance. As PELTs, we feel insecure because of our students’ stereotype of an authentic EFL teacher; we frequently must establish our credibility, especially if we do not have a native accent.

The impact of such experiences on PELTs’ identity is represented in the constant challenges to our credibility, making us feel nervous and insecure about our ability to succeed. This lack of confidence seems to mainly stem from our teachers, students, and even partners’ lack of acceptance, which limits our full potential. We have seen how this affects PELTs who take a passive role in the learning process and limit their possibilities to teach the language. We feel that, by accepting the discourse which regards our variety of English as deficient, we are just imposing limits on our professional aspirations. The lack of recognition of teachers’ English varieties and foreign language education due to promoting a particular accent and pronunciation as a necessary qualification, excludes cultural and personal characteristics that are useful while learning the language. Furthermore, we think that PELTs should be allowed to develop language skills and not feel excluded because of their way of speaking. We should recognize that native-like English does not necessarily represent a skillful teacher, and it should not be considered a defining feature to judge their quality.

Conclusions

Although this study is the result of collaborative autoethnography research, we believe that our experiences during the practicum can serve as valuable insights for the community of PELTs, especially in Colombian public universities. We could understand certain issues related to PELTs from our reflections about being enrolled in an undergraduate program and our pedagogical practicum experiences.

For us, PELTs play a fundamental role in teacher education. Their lack of teaching experience can be seen as a liability, but we argue that it can also be an opportunity for fresh insights into classroom realities, which may lead to pedagogical innovations if appropriate guidance is provided. This, in turn, would reinforce the identity-building process in PELTs since they have a voice in decisions concerning school practice.

It is necessary to analyze the importance and meaning of being a teacher in Colombia to position the profession in the place it deserves; then, future teachers could feel more motivated to contribute to the development of education in the country. The classroom should be a space to experience being a teacher, where PELTs comprehend the educational contexts and feel impelled to resist those imposed colonial pedagogical processes and innovate to transform the vision students at schools have towards learning English.

Finally, we conclude that collaborative autoethnography research can serve as a model for other PELTs to reflect on their own experience and identity development as teachers. They have the chance to act and start transforming the process of learning by becoming agents of change and knowledge builders.