Introduction

Since 1926, the introduction of English into Mexican public schools has experienced changes (Ramírez-Romero & Sayer, 2016). Many state and national programs have tried to reinforce English language teaching (ELT) in public schools to help students improve their performance in the language (Petrón, 2009). These English programs have focused their attention on the elementary and secondary levels of education in Mexico. Consequently, English has become a required subject in the curriculum of Mexican schools. At the tertiary level, however, there are no national guidelines, and each university implements its own English program (Despagne, 2010). This has also been the case in polytechnic and technological universities.

In 2012, the “sustainable international bilingual model” (bilingüe internacional sustentable, or BIS, in Spanish) was created as a response to the need for internationalization and mobility of Mexican university students (Secretaría de Educación Pública [SEP], 2016b). The BIS model intends to increase the number of people who can speak a second language (L2), especially English, and therefore, 29 polytechnic and technological universities have adopted English as a medium of instruction (EMI) since 2012 (Sibaja, 2019). As a result, more teachers and students within the country are in contact with bilingual education where subjects such as mathematics, history, and chemistry, for instance, are taught through English (García, 2009).

Existing research in Mexico (Palomares-Lara et al., 2017; Sibaja, 2019) shows that the implementation of EMI in polytechnic and technological institutions is perceived as a tool that can help faculty and students develop skills in English. Examining EMI in Mexico will likely allow for an understanding of the impact it has on teachers’ and students’ personal and professional lives. Therefore, this study delves into the implementation of the BIS model in one public university in Central Mexico, and the research questions that guided this inquiry were:

Literature Review

To gain an insight into what has been done in the area of ELT in Mexico and the need to look at the BIS model, we will start by providing a historical overview of ELT in Mexico. Then, we will explain the difference between traditional language education programs, bilingual education, and EMI programs. Finally, we will describe the BIS model in Mexico.

English Language Teaching in Mexico: Trends and Outcomes

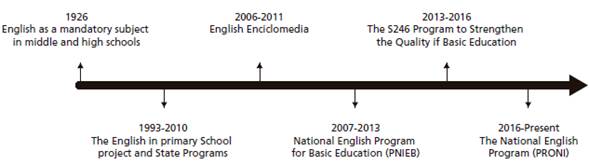

In Mexico, English has been taught in secondary and high schools since 1926 (Calderón, 2015). Until the 1980s, many learners only had their first contact with the language when they started secondary education. This late exposure resulted in students’ low performance in the subject. In 1994, Mexico became a member of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which prompted new economical demands. The proficiency in English was perceived as pivotal for the required technological, economic, and industrial advances; thus, the Mexican government saw the urgency of introducing English in the elementary education curriculum. From then on, diverse national English programs have been issued, especially at elementary education, with the aim of tackling the challenges posed by the teaching of English in Mexico (see Figure 1).

Note. Developed by the authors based on the information from the English national programs.

Figure 1 Development of English Programs in Mexico

We can divide the programs into two major periods: the first one leaning more towards the participation of some States, and the second one with a national project of making English accessible to the majority of the students. The first programs (the English in Primary School Project, State Programs, and Enciclomedia) had the main characteristic that they were operated differently by each State (SEP, 2006). This represented challenges not only in the teaching practices and integration of these programs, but also in the temporary recruitment and status of the teachers, lack of an official curriculum and teacher training, unavailability of material, and, in general, “lack of logistics to support the development [of these programs] across the country” (Trejo, 2020, p. 12).

The second era of the English programs in Mexico started in 2007. According to the SEP (2015), the main objective was to help students attain a B1 level of English by the time they concluded secondary school. This level is described in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) as an intermediate level in which learners are independent users of the language, meaning that they can express their ideas and participate in conversations in a more natural way without being assisted by a teacher (Council of Europe, 2020). The National English Program for Basic Education (PNIEB, in Spanish), the S246 Program to Strengthen the Quality of Basic Education, and the National English Program (PRONI, in Spanish), aimed to strengthen English teaching and learning in public primary schools (SEP, 2016a). However, each program was a hybrid arising from crossing the previous one “without making explicit the relationship with either of them or the reason for the creation of a new program” (Ramírez-Romero & Sayer, 2016, p. 9).

Nevertheless, all these programs have failed in improving the English proficiency of learners, as evidenced by the poor results they have obtained in national tests, and even though the outcomes of the national programs have been questioned, the increased importance of English has motivated institutions, from elementary to university levels, to introduce it into the curriculum. In an effort to help Mexican students acquire the language, alternative bilingual programs have emerged across the country, especially at the university level. But, in order to understand their importance, we now define traditional education programs, bilingual education, and EMI programs.

From Traditional Language Education Programs to English as a Medium of Instruction Programs

Traditional language education programs differ from bilingual education. García (2009) suggests that the realization of such divergence may be difficult due to the types of programs implemented by schools. She points out that:

For the most part, these traditional second or foreign-language programs teach the language as a subject, whereas bilingual education programs use the language as a medium of instruction; that is, bilingual education programs teach content through an additional language other than the children’s home language. (p. 17)

In other words, in traditional language classrooms, the focus is on English to be understood and used-for instance, students in elementary schools learning how and when to use the verb “be.” Conversely, in bilingual education programs, students learn mathematics, physics, history, among other subjects, in English. Bilingual education, as bilingualism, is not only about two languages. It is a complex phenomenon that specifies “how the language is used in the classroom and at home, or the purposes that it serves” (Lozano, 2018, p. 19). English, in particular, has become the lingua franca around the world, and hence, it is the main language taught as a second or foreign language. As Joya and Cerón (2013) assert, “in Latin America, young professionals have oriented their training in a second language exclusively to English as a strategy to improve their job opportunities by enhancing their CVs and professional development” (p. 232). In order to enhance these opportunities, “several governments in the region are developing and implementing policies aimed at increasing English competence among its citizens, and especially among primary and secondary school students” (González & Llurda, 2016, p. 90). From a globalized perspective,

becoming competitive involves the exchange and interchange of information, and the use of a second language as a mandatory fact. The bilingual policy has defined bilingualism as a priority in education for the generation of people who are going to be able to gain access to the labor market. (Joya & Cerón, 2013, p. 234)

This vision continues to preserve the view that true bilingualism is “only that which includes access to the language of an economic empire” (González & Llurda, 2016, p. 90), what de Mejía (2002) calls “elite bilingualism.”

In recent years, a series of EMI programs have emerged which place great emphasis on the importance of learning English as part of a university degree. In these programs, students are “encouraged to develop their linguistic, communicative, academic, and professional competencies without the need to travel to those countries whose language they are studying” (Madrid & Julius, 2020a, p. 26). Studies focusing on analyzing the academic performance of students in EMI programs are still scarce (Dafouz & Camacho-Miñano, 2016; Escobar-Urmeneta & Arnau-Sabatés, 2018; Griva & Chostelidou, 2011; Yang, 2015). In Spanish speaking countries, there have been a few studies that have analyzed how students perceive EMI programs and their level of satisfaction. For example, Madrid and Julius (2020a) examined the academic performance of bilingual and non-bilingual students pursuing a primary school teaching degree and their level of satisfaction with the degree program. Results showed no significant differences between the two groups in eight subjects; differences in favor of the non-bilingual group were present in two subjects: mathematics and learning disabilities. In another study, Madrid and Julius (2020b) aimed to research the students’ level of satisfaction with their program. They examined the profile of Spanish university students in bilingual degree programs that employ EMI by utilizing the bilingual section of the teaching degree course at Universidad de Granada (Spain) as a sample. Their results showed that most students (70%) were satisfied with the program offered, but they also detected some deficiencies, which led to various suggestions as to how university bilingual programs might be improved. In the following section, we will describe the BIS model in Mexico, which emerges from the interest in implementing EMI at universities.

The Sustainable International Bilingual Model in Mexico

The BIS model has tried to incorporate EMI at polytechnic and technological public universities in Mexico. Its creation is a response to the need for internationalization and mobility of Mexican students and its purpose is to increase the number of people who have proficiency in an L2, particularly in English (SEP, 2016b). Saracho (2017, as cited in Sibaja, 2019) contends that:

The aim of the BIS universities in Mexico is to provide bilingual education to low-income students who otherwise would have never had the opportunity to develop English language skills, access scholarships to study abroad, or have opportunities to position themselves in the international industry sector. (p. 10)

The BIS model offers different programs that are mostly taught in English by faculty that have been trained in English-speaking countries (SEP, 2016b). Freshmen within this model must take an English-only first semester to acquire the language. This strategy should enable students to understand content in English as of the second semester. Furthermore, students, with no exception, must learn two other additional languages throughout their programs to expand their opportunities in mixed markets (SEP, 2016b).

The BIS model was firstly implemented in the Technological University of Aguascalientes in 2012, followed by the Polytechnic University of Querétaro in 2013 and by the Polytechnic University of Cuautitlán Izcalli, in the State of Mexico, in 2014. By 2016, 21 polytechnic and technological BIS universities offered bilingual education in 14 states in Mexico (Sibaja, 2019). Moreover, the SEP planned to open one BIS university in each state to comply with the demand from the industry (Nuño, 2017). This national strategy motivated other polytechnic and technological institutions to transition to the BIS model and, in 2019, it was possible to find 29 BIS universities across the country.

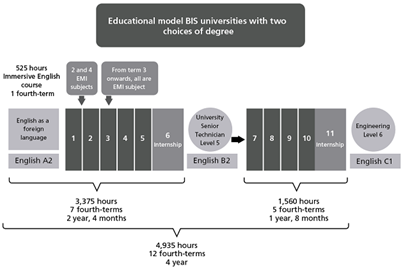

BIS universities work under a specific scheme as shown in Figure 2. Even though this program focuses on the provision of content through English, BIS universities first include an introductory term as several learners arrive with limited knowledge of the language. English allocation is at 100%, and the purpose is to help learners develop basic skills to comprehend content in English as of the next term. By the end, they will have taken 525 hours of English.

Note. Adapted from Nuevo Modelo BIS, by Universidad Tecnológica Laguna Durango, n.d. (https://bit.ly/3Av7FwY). In the public domain.

Figure 2 Scheme of BIS Universities

In the first term, which lasts four months, the model includes two content subjects in English and 10 hours of English as a foreign language (EFL). Here, Spanish is still the dominant medium of instruction due to students’ budding proficiency in English. In the second term, however, the delivery of four content subjects and 10 hours of EFL lessons increase the exposure to English. From term three onwards, the medium of instruction should be 100% in English (Sibaja, 2019).

BIS universities are underpinned by three educative pillars:

Bilingual: BIS universities offer bilingual education through EMI.

International: BIS universities promote international programs that allow faculty and students to develop their skills in English.

Sustainable: BIS universities focus on education that promotes sustainability through projects that acknowledge the importance of the environment.

According to Sibaja (2019), with these three main pillars, polytechnic and technological universities attempt to (a) train students and teachers to become competitive in the global market, (b) support teachers and students to be bilingual citizens who can use the language in diverse contexts, and (c) raise awareness of environmental issues among teachers and students to collaboratively devise projects and design technology that respects and values the environment.

In BIS universities there are two types of teachers: EMI teachers, who are in charge of content subjects, and English language teachers, who concentrate on general English classes. At a first glance, it may seem that these teachers have similar profiles; the reality, however, is that their knowledge base differs. Both EMI teachers and English language teachers should possess specific traits to deliver content. As asserted by Inbar-Lourie and Donitsa-Schmidt (2019), the level of English, the teacher characteristics, and the teaching method employed by EMI lecturers can have an impact on the implementation of EMI in the classroom. As a consequence, “EMI teachers are required to obtain both rich content knowledge and [a] proficient English level” (Qiu & Fang, 2019, p. 2). They should demonstrate that (a) they are knowledgeable of the content, (b) they are acquainted with the specific pedagogical strategies to teach their subject, (c) they know their students and prepare their classes to reach different needs, and (d) they possess language pedagogy skills. In other words, they must know how to help learners build reading, writing, speaking, and listening skills through English content (Li, 2012).

Method

We considered that a qualitative approach suited this study because we focused on how participants lived and experienced bilingual education. According to Denzin and Lincoln (2018), “qualitative research consists of a set of interpretive, material practices that make the world visible” (p. 43). The method that we decided on as the basis for this project is an instrumental case study.

Dörnyei (2007) asserts that instrumental case studies are “intended to provide insight into a wider issue while the actual case is of secondary interest; it facilitates our understanding of something else” (p. 152). That is to say, the researcher makes use of tools that are not the focus of the research; however, using these tools will lead the researcher to understand a more complex phenomenon. This research project attempted to understand the complexities of bilingual education at a public university in central Mexico. Therefore, we focused on distinct stakeholders’ experiences and perceptions.

It is important to highlight that, even though case studies “usually involve the collection of multiple sources of evidence, using a range of quantitative . . . and . . . qualitative techniques” (Crowe et al., 2011, p. 6), we only employed semi-structured interviews due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the lack of access to official documents, programs, or course syllabi. Nonetheless, since the technique was applied to four diverse groups of participants, it was possible to gain a richer picture of the implementation of EMI, and the information about participants’ experiences as teachers, students, and coordinators converged during the analysis.

First, to pilot the interviews, we designed four guides, one for each group of participants. After the feedback was provided by the volunteers who participated in the piloting sessions, we examined the four guides and modified them. The trustworthiness of the interview data assured that coding data was correctly registered using a protocol (Boyle & Fisher, 2007; Cohen et al., 2017). Our study considered construct validity, which assures the connection between questionnaire items and the dimension’s supporting epistemology (Dörnyei, 2003; Michalopoulou, 2017). Likewise, the study considered content validity as it aimed to ensure the domain of content relevant to all items. For conducting the interviews, we had decided to go back to the place where the university is situated. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic affected this arrangement due to social distancing. However, following the categorization of Opdenakker (2006)-in which he includes types of interviews that are not only face-to-face verbal exchanges but also telephone interviews, messenger interviews, and email interviews-we decided to ask the participants if they would participate in an online interview. Each group had a separate interview. Once they agreed, we sent them a letter of informed consent where we explained that we would use pseudonyms to protect their identities. All the interviews were conducted in Spanish,1 audio-recorded, and immediately transcribed. We conducted a thematic analysis using MAXQDA software to analyze the data. The data coding is as follows: I for interview, ET for English teachers, CT for EMI teachers, S for students, and EC for coordinators. For instance, the code I-Silvana-ET represents the participation of an English teacher whose pseudonym is Silvana.

Context and Participants

The university under research is one of the three previously mentioned BIS institutions in central Mexico. In 2017, it transitioned to the bilingual model, offering EMI in the Electronics and Telecommunications and Robotics programs. Later, in 2019, Administration was also offered as an EMI program (Sibaja, 2019).

Participants belonged to four groups: students, English language teachers, EMI teachers, and coordinators of area. The ages of the students ranged from 20 to 33 years old at the time the interviews were carried out. The learners were enrolled in the EMI programs offered by the university: Electronics and Telecommunications, Robotics, and Administration. They were studying in the second, fifth, and eighth semesters when they were interviewed. Having participants from distinct semesters provided richer information about how they perceived the model throughout time, how they adapted to EMI programs, how their learning processes were shaped, and how they could relate to others with similar past experiences.

Three English language teachers were part of the second group (two women and one man). One teacher worked in the Electronics and Telecommunications program and the other two professors taught in the Administration program. The first teacher had worked at the university for eight months and the other two, for two years. Their ages ranged from 28 to 40 when they were interviewed.

For the third group, there was a call to invite three EMI professors. However, only two agreed to take part. The two women in this group worked with content classes in English. One of them had been teaching Human Development and Ethics in English for three years, and the other basic concepts of Administration for six months. When the interviews were carried out, they were 33 and 50 years old.

Finally, in the group of coordinators, there were two participants. They were responsible for coordinating the English area in the programs of Electronics and Telecommunications, Robotics, and Administration. They had worked as coordinators of area for six months. The participants of this group were 24 and 26 at the time the interviews were carried out.

Results and Discussion

During the analysis of the data, distinct themes emerged from the transcriptions of the interviews. For this article, we will focus on the different types of knowledge addressed by the participants as essential components in the development of the BIS model. Then, we will discuss the participants’ perspectives on the implementation of the model.

Teachers’ Knowledge

According to Shulman (1987), effective teaching “requires basic skills, content knowledge, and general pedagogical skills” (p. 6). That is, teachers should not only know about their subject but also about the strategies, the materials, and the learners to demonstrate that they are effective teachers. In this theme, we present diverse types of knowledge participants discussed as an integral part of implementing the BIS model in this polytechnic university: content knowledge, EMI teachers’ knowledge of English, and English teachers’ knowledge of English.

Content Knowledge

Content knowledge is significant as it refers to the teachers’ understanding of a subject. There may be, however, circumstances in which teachers are not acquainted with the discipline and yet they must teach it. For Helena, an EMI lecturer, not knowing the content was a challenge to overcome:

In the subject that I gave, the idea was to help students learn vocabulary. Being honest with you, it is really important. When I studied to teach the content…since, well, I am not an administrator and that was the main conflict . . . I said “Geez! This is more complicated because I am not an administrator.”

It is observable that Helena’s profession did not match the content she was asked to teach. This excerpt implies that teachers’ profiles and expertise may not be considered when programming the classes. However, they are required to teach specific content. In the next excerpt, Amanda-Helena’s student-never perceived the lack of content knowledge:

The teacher . . . helped us express our ideas according to what was expected from us and with the words that we already knew how to pronounce and, well, not only did she know English but she also knew about the subject.

Amanda considered that Helena was knowledgeable of the content. Even though Helena’s profile was different from the subject she was assigned to teach, it is clear that she dedicated herself to expanding her knowledge of the subject so that she could cover the topics in the syllabus.

Unfortunately, not all teachers are willing to learn something new, as Helena did. For instance, Emma, an English coordinator, admitted that some English teachers have reached a plateau:

Regarding teachers, I believe that a great problem is that, as a teacher, you do not progress, that you continue with the same knowledge you have…I believe that if you are not a creative teacher, you will continue with your same knowledge, but it can be very harmful. It can harm students so much.

Emma realized that being an English teacher entails constant learning. As a coordinator, she had to observe classes and noticed that some educators did not progress. She believed that this can harm students’ progress in the language. This excerpt denotes that, even though teachers possess content knowledge, they may not search for opportunities to improve it, which should be essential due to the constant epistemological advances in education. Since professors are part of a bilingual university, this fact demands that they be proficient in English. The following subtheme explains how EMI teachers are seen as users of the language.

EMI Teachers’ Knowledge of English

EMI teachers’ knowledge of English seemed to be a factor that should be considered for the bilingual model to be better implemented. Some students, like Miguel, believed that their EMI teachers did not seem to be qualified to use the language: “I think that our [EMI] teachers were not familiarized with the language . . . They perceived teaching us in English as a mandatory thing…I saw our teachers were very lost.”

This participant observed some EMI teachers’ limited proficiency in the language. Interestingly, this fragment denotes that even when EMI lecturers have an insufficient level of English, they are required or even forced to use it. Paulina, another student, also noticed that lecturers had difficulties in the classroom. Interestingly, she mentioned what some of them expressed concerning teaching their content subjects in English:

Some teachers that gave me content and wanted to give it in English were not proficient or they were learning the language at the same time. Some told us that it was hard for them to teach their subject in English. Others just tried once and then gave up. So, some of them only gave us the materials in English.

Paulina was aware of EMI teachers’ level of English. She also commented that they expressed that it was difficult to teach in English. It seems that EMI teachers started the course using English. However, as they continued, they might not have felt comfortable with their level or they found it challenging, which led them to stop using the language. This, in turn, seems to be affected by the recruitment process they underwent. In the following, the two content teachers indicate how they became EMI lecturers:

It was super simple. The coordinator told me: “This is the subject, and you have to give it in English because it is for the bilingual groups.” Period. That was all. (I-Cecilia-CT)

[My boss] told me that only two teachers could give the subject and that there were several groups. So, then I said: “I bet she is going to give me the subject.” She never explained to me how to do it or what to do. (I-Helena-CT)

From these two excerpts, it is evident that these two professors did not expect to teach their content subject in English because, initially, they were not hired as EMI lecturers.

The limited English proficiency that students observe among their teachers most likely comes from the latter’s lack of preparation and expertise in EMI. In addition, the recruitment process at this institution may not be strict, and the administration requires some personnel to teach content in English only because they had previous contact with the language. Since this is a bilingual institution, the demand for EMI teachers must be high and the solution provided was hiring teachers who have certain skills in English, even if these do not reflect the B2 level required by the model.

It is additionally perceived that no classroom observations are carried out. No process ensures that students experience bilingual education as it is stipulated by the coordination of polytechnic and technological universities. If EMI faculty were observed and received EMI training and courses to learn the language, students would not perceive their teachers’ low level of English. Regarding English language teachers’ proficiency, some participants also addressed the theme, as we see next.

English Teachers’ Knowledge of English

Since this polytechnic university is bilingual, professors who are responsible for teaching EFL must demonstrate they are proficient in the language. For some students, like Laura, the experience with English teachers has been positive: “In my opinion, the English teachers are super qualified. They speak the language very well and prepare us well.”

Laura acknowledges that English language teachers are proficient and qualified to be in front of the class. Similarly, Ximena and Christian considered that their teachers could use the language proficiently.

The teacher we currently have explains very well. He also has an advanced level of English. Sometimes he uses Spanish when we do not understand, but he almost always speaks in English. (I-Ximena-S)

Talking about their proficiency in English, I have had good experiences. Each of them teaches differently, but in general, I consider them qualified to be there. They speak English very well. (I-Christian-S)

Both students consider that English teachers are proficient, which has allowed for positive experiences even when teachers use Spanish. This might have been due to the requirements that English teachers have to fulfill. Nazario, an English coordinator, provided information about those requirements:

They have to hold a bachelor’s degree, a language proficiency certificate with at least a B2, it can be the TOEFL…Also, they need to demonstrate they have experience teaching English and obviously, they have to give a demo class in which we can prove that everything stated in their documents is evident in the demo class.

Whereas strict requirements for English teachers are observable, EMI faculty does not seem to have a formal recruitment process. These discrepancies within the institution need to be addressed as they may have negative impacts on the provision of bilingual education. We will now turn to discuss how the participants perceive the development of the model.

The Participants’ Perspectives on the Implementation of the Bilingual Model

In this section, we will discuss two aspects that emerged from the data. First, we will show the complexities of trying to implement this bilingual model and how participants doubt this is possible. Second, we will discuss aspects that hinder the effective implementation of the model.

Towards Bilingual Education?

Students and teachers perceived that this polytechnic university has a different dynamic. Yet, learners provided evidence that may unveil the reality of bilingual education at this institution. For instance, when Laura, a second-semester student, was asked about EMI classes, she answered: “Supposedly, there is a subject that has to be given in English, but due to the complicated situation we are experiencing, we still do not have any content subjects in English.”

Laura believed that the COVID-19 pandemic was an obstacle to receiving content through English. According to the stipulations of the model, a student in the second semester should be given two EMI classes. Perhaps the pandemic affected the organization, and teachers were more concerned about the content than the language. Similarly, Ximena, another student, thought that the pandemic allowed for some changes in EMI classes:

I believe that our teachers were considerate and agreed to teach the content in Spanish. In that way, it would not be difficult for us to understand or to miss any knowledge because we would practically be missing a semester.

Ximena considered that her teachers were sympathetic and preferred to use Spanish to help them understand the subjects. The pandemic possibly affected the dynamic of EMI. Nevertheless, students in more advanced semesters revealed that there are inconsistencies in the EMI classroom. Julia, for example, mentioned:

Right now, we are supposed to be taking physics and calculus, but they are not in English. Sometimes the exercises or exams are in English, and our reports should be in English, but our teachers do not speak in English.

According to the general guidelines, Julia should receive all her classes in English. As she stated, she only had two classes, and they were not given in the language. Once again, it is noticeable that EMI lecturers are not instructing in the language. An interesting finding was that for Miguel, an eighth-semester student, the bilingual experience disappeared some time ago:

In the end, I believe that our teachers gave up because, as of semester four, they stopped teaching content in English. They went back to the traditional thing again. They used Spanish and, well, the English subject continued. I mean, in the end, it did not work.

Miguel was almost finishing his program, and it seems that his teachers were not able to maintain the bilingual experience as it should be expected. For other students in the same semester the experience was similar. The following excerpt illustrates that EMI classes are inexistent:

To be honest with you, I do not take any content classes in English. I believe it is a good idea because, as I mentioned, it is complicated. Those subjects are complicated even in Spanish because we use a lot of numbers, and that is complex. So, I cannot imagine what that would be like in English. (I-Christian-S)

Christian’s excerpt implies that EMI programs are not consistent and that, perhaps, the institution should evaluate what programs can be offered under a bilingual scheme. In that way, teachers and students’ experiences could be improved. The following subtheme discusses other aspects that can be affecting the implementation of EMI at this university.

Aspects That Hinder the Effective Implementation of the Model

Participants mentioned some aspects that should be considered for the model to be developed more appropriately. One EMI teacher mentioned that culture was one factor that affects the implementation of the model:

I think that what we are missing is culture. The model is good. It is a good idea, but, as I have mentioned many times, we cannot implement something that works well in Europe in Mexican culture because we are so different. Mexicans are like, “yeah, tomorrow!” (I-Helena-CT)

Helena acknowledged that bilingual education is an advantage, but she also implied that perhaps Mexicans are not ready to embrace bilingual education due to cultural beliefs. For Silvana, an English teacher, the context of the university may also pose challenges as she explained: “I do not really know if the model is useful in the context where we live since many students are not in contact with different companies. Their parents are businessmen and have never required any knowledge of English.”

The university is situated in a region where commerce has a great impact on the lives of many businesspeople. For Silvana, the learners’ context plays a significant role. She questioned the usefulness of such a model due to students’ previous contact with the language and how much they will require it in the future. As she mentioned, students’ parents are mainly traders and have built their heritage throughout the years. Some students plan to inherit their parents’ businesses and they do not see English as a relevant tool in their lives, and that is why bilingual education might not seem important to them. Regarding the usefulness of the language, another English teacher also questioned the implementation of this model:

Regarding the model, we try to do our best, and, in the attempt, we lose the vision. Students are required to achieve certain levels of English to continue with their studies, and it is subjective to try to measure under those standards; measuring the language when you are not really measuring its practicality and usefulness. All of this in a context that requires students to demonstrate they can use English and content concretely. (I-Carlos-ET)

Carlos believed that the way students were evaluated was not related to how much they could apply their knowledge to situations that are connected to the language and their careers. It looks as though the most important aspect was to pass the subjects. This has resulted in a challenge for some students like Ximena:

Why do they demand that we learn English? I mean, we may use it and it can be helpful to us, but I felt angry when they told us that if we did not achieve the levels, I could not continue with my major or that they would kick me out of school even when I have good grades in other subjects.

It is observable that the school measures students’ progress and that attaining certain levels of English is mandatory. Otherwise, learners cannot continue with their programs. Ximena likely encountered challenges to reach the levels required and she did not understand why she had to abandon her studies if she was not proficient in English. This excerpt denotes the authorities’ misbeliefs that if students do not acquire English, they cannot become successful professionals.

Another aspect that may hinder the model was the context. Nazario, an English coordinator, mentioned:

I believe the context plays a significant role. There can certainly be teachers who are good at teaching their subjects, but we live in a Hispanic context. I mean, the predominant language here is Spanish…Therefore, if you create a model, you have to check that your teachers satisfy the model’s needs…If you cannot find those teachers in your context, you must train them…and that takes a long time.

Nazario considered that the model could work properly if teachers were trained to fulfill the needs of bilingual education. Unfortunately, not all EMI professors are experts in English. Although he considered that the university could help professors, he also stated that this process takes time. This might be the reason for learners to experience bilingual disenchantment shortly after they started their studies.

In general, factors such as culture, the applicability of the language, students’ context, and teachers’ profiles play a significant role in the development of the model. This suggests that focusing attention on these aspects could have better outcomes at this polytechnic university. For instance, if the institution provided training, teachers could become bilingual, and students could experience bilingual education throughout their programs. Students could also see that, regardless of their context, English is a skill that may provide them with enriching opportunities. Finally, the university could position itself as a real bilingual school.

On the subject of teachers’ knowledge, students and teachers considered that knowing the language, the content, and students’ needs, context, weaknesses, and strengths are factors that had an impact on the development of the model and the progress of learners at this university. Concerning the implementation of the model, it is perceived that the bilingual model was efficient during the first semester; however, factors such as the lack of training, the context, and the usefulness of the language in authentic environments contributed to a deficient development of EMI.

Conclusions

This research project aimed to explore the implementation of a bilingual model in a polytechnic public university in central Mexico. Additionally, it sought to explore the experiences of English and EMI teachers, students, and coordinators involved in the model.

EMI teachers perceived their experiences were negative due to their lack of proficiency in the language. They acknowledged they were not acquainted with EMI and were not initially hired as EMI faculty. Therefore, they had difficulties delivering content in English. English coordinators acknowledged the importance of teacher training; however, more efforts need to be visible in this aspect since teachers mentioned they need constant training to be able to teach their classes in English. Students perceive the difficulties teachers have when trying to teach content in English, however, they do appreciate and value when teachers are creative and encourage them to learn more.

Through the participants’ voices, it was possible to see what aspects of EMI could be improved at this university. It is observable that, after three years of implementation, the stakeholders still struggle to comply with the requirements. This paper will hopefully serve the administrators at this institution to evaluate how they have implemented EMI and how they can assist lecturers to improve their English and pedagogical-content skills. The observable lack of training and the limited information the stakeholders have about EMI has likely influenced the development of this program. It is recommended that the stakeholders work collaboratively and devise strategies to train teachers. Additionally, they should conduct a needs analysis to understand what aspects are paramount to be resolved in the near future and what modifications are feasible due to the context, the materials, the policies, the teachers, the financial support, and the type of teachers and students. Otherwise, there is a risk this BIS model faces the same scenario as the national English programs. Over the years, the efforts of implementing English formally in the Mexican educational system have gone through different programs. However, these have not provided positive results and the same challenges are still present and unsolved. Polytechnic and technological universities aim for a bilingual model, but we recommend looking at the history of English teaching in Mexico and its realities so that the BIS model can succeed and overcome the challenges faced by previous programs.

From the analysis of the data, we were able to illustrate how the participants perceive EMI and some of the challenges and benefits experienced. In addition, at a global level, this research adds to the ongoing discussion of EMI in higher institutions as it sheds light on the situation of EMI in the Mexican context. To obtain a clearer picture of EMI and the participants’ experiences, further research should include more than one technique to gather data and more participants. Observations, journals, and focus groups would likely provide more insights into the situation of EMI at BIS universities. Future research should continue investigating EMI programs in other polytechnic and technological universities across the country as many of them have adopted or will transition to this type of bilingual education in the years to come.