Introduction

This paper discusses the use of the repertory grid technique (RGT) as a credible research tool in the field of teaching English as a foreign language (TEFL), specifically for research focused on issues related to teacher beliefs. As an example of its use, we describe a case study concerning foreign language teachers’ cultural perceptions about good pedagogy. Because research into culture is particularly fraught with methodological difficulties (Baldwin et al., 2006), the topic serves as a useful focus to illuminate some of the advantageous features of the RGT.

The role of culture in second and foreign language teaching and learning is well established, and research on the topic is extensive. In the last decade or so, at least four literature reviews on the subject have been published (Álvarez-Valencia, 2014; Lessard-Clouston, 2016; Risager, 2011; Young et al., 2009). Most empirical studies comparing and contrasting cultural views on pedagogy (language or otherwise) have typically relied on questionnaires, often supported by structured interviews, using previously validated and standardized items (e.g., Clark-Gareca & Gui, 2019; Liu & Meng, 2009; Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], 2009; Pawlak, 2011; Schulz, 2001). These data elicitation techniques are not without problems. Questionnaires have been criticized for their susceptibility to common method variance, which occurs when respondents’ answers do not genuinely reflect their authentic views but are instead influenced by the instrument’s design (Gorrell et al., 2011). Research has identified several ways in which this kind of method bias can pollute questionnaire data (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

To mitigate the inherent defects of questionnaires, many researchers support them with structured interviews. Such interviews, however, are subject to their own limitations, including the possible downsides of “subjectivity, the generalisation of the findings, conscious and unconscious biases, influences of dominant ideologies and mainstream thinking” (Diefenbach, 2009, p. 875). When data from questionnaires and structured interviews are used together, problems arise in aligning data derived from the two methods. Poor alignment can be attributed to

the complexity and instability of the construct being investigated, difficulties in making data comparable, lack of variability in participant responses, greater sensitivity to context and seemingly emotive responses within the interview, possible misinterpretation of some questionnaire prompts, and greater control of content exposure in the questionnaire. (Harris & Brown, 2010, p. 1)

The RGT is a type of structured interview associated with the field of personal construct psychology (PCP). Combining the best features of both qualitative and quantitative techniques, the grid technique militates against some of the weaknesses of both. First, the structure of repertory grid interviews helps mitigate method bias. As with any qualitative interviewing method, there is always a danger that the RGT researcher may impose constructs or lead participants. However, because the main role of the interviewer is to focus and clarify a participant’s responses rather than guide the interviewee through a series of predetermined questions, the potential for “leading the witness” is reduced. Second, unlike elicitation techniques that necessitate post-hoc thematic analyses, the repertory grid process brings the most essential themes of an interview immediately to the fore. Finally, because RGT data is amenable to statistical analysis, it allows researchers to uncover patterns in participant responses which reflect psychological relationships within the “construing systems” of both individuals and groups (Fransella et al., 2004, p. 81).

The following is a consideration of the RGT as a methodological instrument. Specifically, the paper describes an analysis of the commonalities and individuations of the pedagogic beliefs of nine language teachers at a public university in central Mexico in order to illustrate how the RGT can profitably be employed in the field of applied linguistics and TEFL. First, an overview of the RGT is provided. Second, several studies in the field of TEFL that have utilized RGT interviews are reviewed. Third, literature concerning the impact of cultural beliefs on language pedagogy is presented to situate the subsequent discussion of repertory grid analysis. Finally, a case study is presented as one example of how the grid technique can be used to capture information about cultural dissimilarities in teachers’ pedagogic beliefs and, by extension, to capture information concerning pedagogic beliefs in general.

The Repertory Grid Technique

The RGT is a specific type of interview utilized to analyze the content and structure of the implicit theories that people rely on to construe reality. Of the methodologies associated with Kelly’s (1955, 1963) theory of PCP, the RGT is the most well-known.

Although repertory grids were initially developed by Kelly for use within the field of clinical psychotherapy and primarily focused on the individual level of analysis, scholars in other disciplines have adopted its premises and employed its methods to understand belief systems at the collective level (Jankowicz, 1987). Kelly’s (1955) writings on “commonality” and “sociality” explicitly address the tendency of groups to create tacit theories of the world. People, of course, define themselves in overlapping ways as members of ethnicities, genders, economic classes, age cohorts, and professional or occupational groups. All such sub-cultures build on a shared perspective that orders their respective “fields of experience to provide identification and solidarity for its members” (Kay, 1970, as cited in Diamond, 1982, p. 401). As Wright (2004) points out, when individual constructions are brought together, “certain underlying collective frames of reference emerge that reflect a sense of common understanding and shared meaning” (p. 354). Sechrest (2009) argues that uncovering these frames likely has more definite implications for research than any other area of Kellian theory.

The RGT is a “two-way classification of data in which [entities or] events are interlaced with abstractions” (Shaw, 1984, as cited in Zuber-Skerritt, 1988, “The repertory grid” section, para. 2). Repertory grids “reflect part of a person’s system of cross-references between their personal observations and experience of the world . . . and their personal classifications or abstractions of that experience” (Zuber-Skerritt, 1987, p. 604). Using Kellian nomenclature, personal observations and experiences are denominated “elements”; abstractions of experiences are denominated “constructs.”

Elements are a set of events and entities external to the interviewee. In clinical psychology, for instance, elements might be family members. In marketing, elements might be a set of different cars, or vacation destinations, or cellphones. In the current research, participants were asked to think about their past teachers. The choice of “past teachers” as grid elements is premised on Lortie’s (1975) theory of the “apprenticeship of observation,” which denotes the internalization of teacher roles, identities, and practices that occurs over the course of an instructor’s time as a student. These beliefs about teaching constitute what have been referred to as “folk pedagogies,” a term which emphasizes the cultural dimension of how students come to understand teaching (Joram & Gabriele, 1998).

Constructs, Kelly (1955) asserted, are the personal theories that arise when humans compare or contrast any two entities. Humans develop hypotheses based on these theories which, in turn, are tested through on-going “experiments” (i.e., interactions) with their environments (Beail, 1985; Fromm, 2004; Hardison & Neimeyer, 2012). In other psychological approaches, these theories may be variously referred to as personality, attitudes, habits, reinforcement history, information coding system, psychodynamics, concepts, or philosophy (Fransella et al., 2004). Borrowing Jerrard’s (1998) denotation, in this paper constructs are defined as a “basic dimension of appraisal” (p. 41).

The constructs in Kelly’s (1955) model are always bipolar. When elicited during an RGT interview, the two poles are designated the emergent pole and the implicit pole. The emergent pole refers to the original comparison or contrast given by the participant; the implicit pole is elicited by asking the participant to provide what they believe to be the semantic opposite of the emergent pole. Because each construct is bipolar, it is possible for participants to use a numerical scale to evaluate each element. That is, each completed grid can be thought of as a “personal differential questionnaire” (Tomico et al., 2009, p. 57) that participants can use to numerically rate elements in terms of constructs, allowing for a variety of statistical analyses to be conducted.

The Repertory Grid in TEFL Research

Since its development in the 1950’s, the repertory grid has been adopted by a wide range of researchers with interests outside its original psychotherapeutic context (King & Horrocks, 2010). Indeed, the RGT has proven to be such a useful instrument for eliciting and analyzing verbal commentaries that the technique is often dissociated from its underlying theory. Although scholars within the field of PCP warn against decoupling repertory grid interviews from Kelly’s theories of personality (Beail, 1985; Denicolo & Pope, 1997), researchers outside the area of PCP have found repertory grids to be a practical, stand-alone data collection technique: Repertory grids have been employed in more than 2,000 books, book chapters, research articles, and academic work in a wide variety of fields (Luque et al., 1999; Neimeyer et al., 1990; Saúl et al., 2012), with an average of 100 works utilizing the technique published each year (Saúl et al., 2012).

In the field of general education, there are numerous studies of teacher development and cognition based on repertory grid data. However, only a handful of investigations in the field of TEFL have utilized the RGT. One of the first of these was a study carried out by Bodycott (1997), who investigated conceptions of the “ideal teacher” among 12 preservice English language instructors in Singapore. The author supplied the grid elements, all of which were based on social and professional identities such as “self,” “past self,” “ideal self,” “mother,” “father,” “school principal,” and “language teacher.” Bodycott reported that the research participants’ opinions about “good” teaching emphasized the personal traits and values of language instructors rather than pedagogic knowledge.

Sendan and Roberts (1998) used the RGT to investigate the complexities of change in student cognition. Arguing that much of the teacher cognition literature defines thinking in terms of one-dimensional “lists” of variables, they instead approached student-teacher cognition as a dynamic developmental process. Through a diachronic, statistical analysis of one student-teacher’s repertory grid data, the authors found that the participant’s beliefs about effective teaching were indeed dynamic, changing not only in terms of content but also in terms of structure.

Murray’s longitudinal investigation (2003, as cited in Borg, 2006) focused on the development of language awareness among preservice teachers. Over the course of a seven-month class in English as a second language (ESL) pedagogy, participants were interviewed three times. Murray provided samples of learner language, native-speaker language, and coursebook language and asked his research participants to discuss similarities and differences between them. Murray’s data analysis was unconventional: Although he used a repertory grid elicitation technique, actual grids were not constructed. Instead, the researcher analyzed interview transcripts and located constructs within them. In subsequent interviews, he then tracked how these constructs changed and were supplanted by others.

Yaman (2008) relied on repertory grid interviews to follow a single English language teacher’s development over the course of a one-year, in-service training program. The author emphasized that the RGT had great potential as a tool for reflection, concluding that the technique allowed her to “gain access to and monitor changes in the teacher’s personal theories with relatively less imposition of the researcher’s own construction of the issues than would have been possible with methods such as observations, questionnaires or checklists” (p. 38).

Kozikoglu (2017), in an RGT study of 36 prospective teachers in Turkey, aimed to identify their cognitive constructs regarding ideal teacher qualifications. Six participants were selected from the department of foreign language education. In all, 356 cognitive constructs were produced. The author concluded that, according to the study, “ideal teachers should have qualifications such as humaneness, joviality and personal values as well as professional knowledge (content knowledge and pedagogical skills)” (p. 72).

More recently, Eren (2020) investigated the intercultural views of three instructors from Germany, Syria, and Iran regarding the concept of teacher autonomy. Eren gathered data using repertory grid interviews along with traditional semi-structured interviews and classroom observations. Findings suggested that the teachers understood “teacher autonomy” in similar ways, notwithstanding their national origins.

The Impact of Cultural Beliefs on Language Pedagogy

The widely acknowledged idea that socio-cultural forces influence teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and professional practices is encapsulated in the term situated cognition (Brown et al., 1989). This concept is based on the notion that knowledge is always developed within a given context. Teaching and learning are never neutral acts: They are inseparable from their socio-cultural settings (Brown et al., 1989; Lave, 1988; Lave & Wenger, 1991). Through classroom activities, teacher models, and peer influence, students are apprenticed into a particular culture of learning that reflects wider cultural assumptions (Lave, 1988). Teachers are likewise enculturated. The anthropologist Conrad Kottak (2004, as cited in Read et al., 2009) defines enculturation as

the process where the culture that is currently established teaches an individual the accepted norms and values of the culture in which the individual lives. The individual can become an accepted member and fulfill the needed functions and roles of the group. Most importantly, the individual knows and establishes a context of boundaries and accepted behavior that dictates what is acceptable and not acceptable within the framework of that society. It teaches the individual their role within society as well as what is accepted behavior within that society and lifestyle. (p. 52)

There is considerable empirical evidence to support these ideas. For instance, the OECD’s Teaching and Learning International Survey (2009) compared perspectives on pedagogy in 16 OECD and seven partner countries. Findings indicated that the influence of culture and pedagogical traditions on teachers’ beliefs and practices is “exceptionally high” (p. 96). Schleicher (2018)-summarizing the OECD’s most recent 2018 survey of teaching and learning-reaffirmed the cultural dimensions of teaching, noting that “the meaning of teacher professionalism varies significantly across countries, and often reflects cultural and historical differences” (p. 29).

Language education, like all education, is a cognitively situated activity. Whether overtly or covertly, a process of “cultural scripting” (Stigler & Hiebert, 1999) encourages both teacher and students to conform to the socio-cultural practices of their educational environment.

How socio-cultural forces influence teacher and student perspectives on foreign language pedagogy has been a fertile area of study in TEFL research (see, for instance, Amiryousefi, 2015; Widiati & Cahyono, 2006; Yoo, 2014). Indeed, the large number of such studies supports Atkinson’s (1999) assertion that “except for language, learning, and teaching, there is no more important concept in the field of [TESOL] than culture” (p. 625).

Given the sheer volume of research focused on questions of culture, it is remarkable that there are relatively few studies in the field of TEFL devoted to cross-cultural comparisons. The exception here is the research contrasting Chinese and Western beliefs and attitudes about EFL pedagogy (Anderson, 1993; Burnaby & Sun, 1989; Clark-Gareca & Gui, 2019; Degen & Absalom, 1998; Hong & Pawan, 2015; Rao, 2013; Shi, 2009; Simpson, 2008; Stanley, 2013; Zhang, 2016; Zhou et al., 2011). Other comparative studies, however, are relatively rare (Aubrey, 2009; Can et al., 2011; Liu, 2004; Pawlak, 2011; Richter & Lara-Herrera, 2017; Rubenstein, 2006; Schulz, 2001).

Method

This exploratory study is concerned with the tacit beliefs of foreign language teachers concerning cultural perceptions of good language teaching. It is offered as an example of the usefulness of the RGT, both in terms of the productiveness of elicitation and the utility of subsequent analysis.

Participants

Possible participants were identified through convenience sampling. Nine second and foreign language teachers working at a university in central Mexico ultimately agreed to take part in the study: three Spanish language teachers, three French teachers, and three English teachers. A larger pool of participants was deemed unnecessary given that this article aims to illuminate the RGT as a methodological instrument rather than to delve deeply into matters of culture, per se.

Procedure

The participants were interviewed individually. Grid elements were chosen by the participants, who were asked to think of six of their past teachers: an excellent language teacher, an excellent content teacher in another field, an average language teacher, an average teacher in any subject, a poor language teacher, and a poor teacher in any subject. They were also asked to think of themselves at three moments during their teaching career: in the past, in the present, and in the future. Through researcher-directed dyadic elicitation, the participants were subsequently asked to compare and contrast the elements they had chosen, thus generating a list of personal constructs. At the intersection of each element and construct, participants were asked to provide a numerical rating, representing an evaluation of each element in terms of its corresponding construct’s emergent and implicit poles.

To analyze any group as a whole, it is necessary to homogenize individual responses. This is generally achieved by pooling all the participants’ constructs and categorizing them according to the meanings they express. There are essentially two ways of going about this. The first, referred to as “bootstrapping,” consists of analyzing the collected constructs systematically and identifying the most salient connections or themes. The second method requires that the researcher preselect a set of constructs, generally one encountered in the literature or one that is theoretically based (Jankowicz, 2004). To overcome the highly idiosyncratic nature of the results and to create a standardized classification scheme, we employed the second option. Constructs were placed into a number of categories suggested by Dunkin (1995). Dunkin’s taxonomy breaks teaching into eight distinct dimensions: teaching as structuring learning, as motivating learning, as encouraging activity and independence in learning, as establishing an atmosphere conducive to learning, as experience, as content knowledge, as pedagogic knowledge, and as personal/professional orientation. The resulting categorizations allowed for both inter- and intra-grid analyses of the constructs elicited from the English, Spanish, and French groups. While sacrificing some detail in each of the individual grids, this system allowed for the identification of trends common to all of them (Jankowicz, 2004).

We analyzed the categories in terms of three dimensions: (a) dominance, (b) importance, and (c) semantic similarity. Dominance refers to the degree of inter-group agreement about the importance of a given construct category. If, for instance, constructs associated with “structured learning” were elicited more often from one group than another, one could plausibly conclude that structured learning is more important to the first group than to the second. In PCP, elicitation order is used to measure a construct’s importance to a given participant (Tomico et al., 2009). An importance index was created by calculating the normalized order in which constructs were elicited (with constructs reported first being considered more important to the participant than those reported later). Finally, semantic similarity can be computed using hierarchal cluster analysis, which in turn can be visually represented by a dendrogram of taxonomic relationships. Such an analysis is useful because it provides a way to understand the extent to which given elements and constructs are seen as similar in meaning, both inter- and intra-personally.

Findings and Discussion

In all, the nine participants generated 177 constructs. The average number of constructs among the English teachers was 21; among the Spanish teachers, the average was 26; and among the French teachers, the average was 11. In all, 1,770 pieces of data (i.e., all emergent and implicit constructs plus the participants’ ratings on the constructs) were elicited.

Dominance and Importance Measures

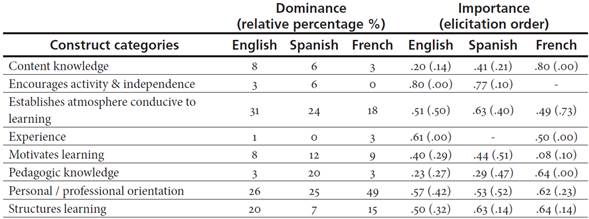

Table 1 displays the relative percentages (i.e., dominance) for each construct category as well as the elicitation order (i.e., importance) for the English, Spanish, and French teachers. The elicitation order index was derived by calculating the mean of the order of all constructs within each construct category. Based on the total number of constructs generated, the order of the constructs was normalized for each participant to a range of 0 to 1: a 0 value reflects the first construct that was elicited, and a 1 value reflects the last construct. A standard normalization formula was used:

X normalized = (b - a) * [ (x - y) / (z - y) ] + a

This can be reduced to

normalized order = order rank - 1 / total constructs - 1

The standard deviations (which are critical for estimating the homogeneity of a category of constructs in the relative order) are included in parentheses after each rank.

Table 1 Dominance and Importance Measures

Note. The dominance of each category (measured by the relative percentage of total constructs) and the importance of each category (measured by the elicitation order) for the English, Spanish, and French teachers. Standard deviations are displayed in parentheses.

The dominance analysis highlighted major alignments and disjunctures between the three groups. For instance, the relative percentage measures demonstrate that all of the teachers regarded the personal and professional aspects of their work as significant. Constructs in this category, which included “willingness to grow,” “ability to adapt,” and “dedication,” demonstrated a commitment towards instructional excellence and professional development. The French teachers emphasized this aspect of their work: almost 50% of their constructs had to do with their personal and professional orientation. Overall, all three groups shared beliefs about the importance of establishing a classroom atmosphere conducive to learning. The English and French teachers were alike in that both groups generated a significant number of constructs having to do with structuring learning, such as careful planning, organization, and assessment (20% and 15% of total constructs, respectively). The Spanish teachers placed a great deal of emphasis on the importance of pedagogic knowledge (20% of the total constructs generated by this group).

These findings are enhanced by the nuance afforded by an analysis of the importance indices. While the English teachers offered the largest number of constructs related to establishing an atmosphere conducive to learning, according to the elicitation index, content and pedagogic knowledge may be more important to them (these constructs were ranked as 1 and 2, respectively). The agreement between the English teachers regarding their rankings, as reflected by the low standard deviation scores, adds credence to this claim. Pedagogic knowledge was similarly important to the Spanish teachers. Interestingly, the relative percentage here is more in line with the salience of the construct. That is to say, the Spanish teachers both created a high number of constructs associated with pedagogic knowledge and rated these constructs as the most important to their practice. Finally, for the French group, although personal and professional orientation was the most “replete” category (comprised of 49 constructs), “motivating learning” was ranked as the most important construct.

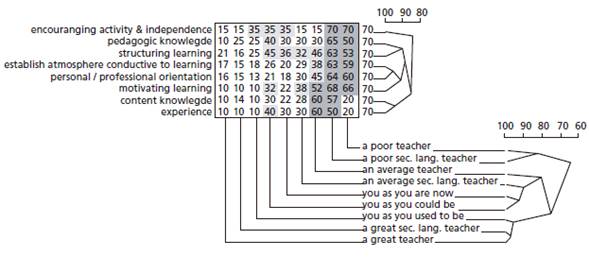

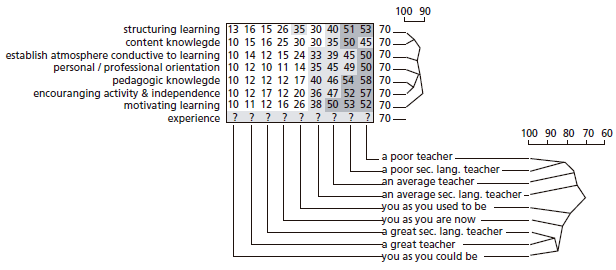

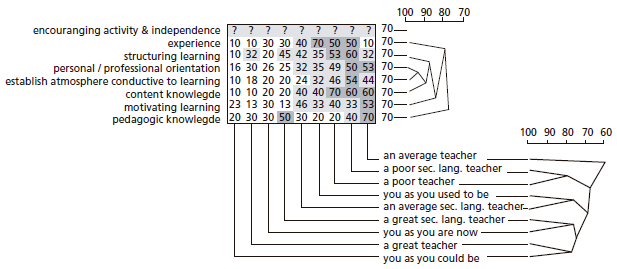

Semantic Similarity Measures

Semantic similarity is a metric defined by how closely or remotely an individual perceives the distance between the meanings of two (or more) units of language, concepts, or instances (Harispe et al., 2015). When a hierarchical cluster analysis of correlations is applied to the numerical data in a repertory grid, the more that constructs or elements are alike, the closer they approximate a score of 100, which would signify a perfect correlation. Thus, in Figure 1, the construct categories “establish an atmosphere conducive to learning” and “personal and professional orientation” are closely linked (a 95.7% match). This suggests that for the English teachers, an instructor who makes students feel secure, is approachable, and “nurturant” (Dunkin, 1995, p. 24) and is probably also a teacher who tends to integrate their personal and professional identities (Sabirova et al., 2016). For the English teachers, content knowledge and experience were also highly correlated (94.3% match). In terms of elements, the English teachers viewed being a language teacher in roughly the same terms as being any other type of teacher (94.4% match).

Figure 2 shows that the Spanish teachers also believed there to be a strong connection between establishing an atmosphere conducive to learning and an instructor’s personal and professional orientation (94.4% match). In comparison to the English participants, the Spanish group, however, viewed the pedagogic characteristics of language teachers as being relatively distinct from the characteristics of the non-language teachers they had identified as elements (85% match).

The French teachers viewed both the construct categories and the supplied elements as semantically independent units with relatively little overlap between them. As seen in Figure 3, for this group, the concepts “establishing an atmosphere conducive to learning” and “personal and professional orientation” were also the most semantically similar. However, unlike the English and Spanish groups, these concepts only matched at a relatively low 89.6%. For the French instructors, a “great teacher” and a “great second language teacher” only matched at approximately 75%, suggesting that for this group, language teachers possess several characteristics and beliefs that distinctly separate them from teachers in other fields. To understand these differences better, follow-up interviews would have to be conducted.

Conclusion

The repertory grid is an interview technique that explores the structure and content of the implicit theories people rely upon to construe their experiences. As mentioned in the introduction, the technique merges the strengths of both qualitative and quantitative approaches in a way that mitigates a number of methodological difficulties associated with other qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods procedures.

In this study, nine language teachers at a public university in central Mexico were interviewed about their conceptions of “good” language pedagogy. The dominance and importance measures demonstrate that all the language teachers viewed the personal and professional aspects of their work as important. All three groups shared beliefs about the importance of establishing a classroom atmosphere conducive to learning. Both the English and French teachers generated a significant number of constructs having to do with structuring learning. In addition, the Spanish teachers placed a high emphasis on the importance of pedagogic knowledge. Findings like this demonstrate the usefulness of the technique in uncovering tacit, pedagogical beliefs, a knowledge of which would, of course, be useful in second language teacher education, particularly in terms of opportunities for self-reflection and monitoring changes in pedagogical perspectives over time.

As this research was premised on creating an example of how repertory grids function, the study must be considered exploratory and illustrative. And as with any such study, the results must be heavily caveated. In the present case, first, the concept of culture is infamously “messy” (Fives & Buehl, 2012; Pajares, 1992) and thus would have to be carefully disambiguated were this research to advance beyond its current state. Second, there are unresolved questions regarding sample size. The literature is notoriously unresolved as to requisite sample sizes in repertory grid investigations, with different researchers advocating sample sizes of between six and 25 to approximate the universe of meaning within a given population (Dillon & McKnight, 1990; Dunn, 1986; Ginsberg, 1989; Hassenzahl & Trautmann, 2001; Heckmann & Burk, 2017; Moynihan, 1996; Tan & Hunter, 2002). In any follow-on study, the question of proper sample size would have to be carefully addressed. Lastly, were the research to be carried further, whether to rely on pre-formulated categories or to undertake conceptual content analysis is a question that would need to be resolved.

These methodological concerns, however, are largely tangential to the purpose of the current article, which offered a small-scale study to elucidate how RGT interviews are conducted and to present a few of the ways in which the resultant data can be analyzed. As should be apparent, the RGT’s usefulness is in no way limited to the topics explored in this article. It is a data elicitation and analysis approach suitable for any study focused on teacher, student, or shareholder beliefs. It allows for comparisons of beliefs between a variety of people on a wide range of topics. In sum, repertory grids are distinguished for their ease of use, their utility in precisely defining concepts without the need for post hoc analyses, their usefulness in uncovering connections between seemingly dissimilar concepts, their ability to restrain researcher bias, their high degree of validity, and their amenability to several types of statistical analysis grounded in participants’ qualitative and idiosyncratic views of the world.