Introduction

During the last decade, the discussion about language assessment in the English-speaking context has involved concerns such as immigration and citizenship (McNamara & Ryan, 2011; Shohamy & McNamara, 2009), and entrance to universities (Deygers, van den Branden, & van Gorp, 2018; Deygers, Zeidler, et al., 2018). This has brought with it the issue of justice linked to assessment, which has taken on great relevance due to the social implications some uses of tests have in terms of equity in a broader sense. As McNamara and Ryan (2011) affirm, “justice questions the use of the test in the first place, not only in terms of its effects and consequences but in terms of the social values it embodies” (p. 165). In Colombia, there has been little discussion of these concerns; yet, the issue of justice in assessment needs to be considered when it comes to the classroom setting, where context plays an important role (Scarino, 2013). In this sense, I would rather use the term fairness since it basically refers to issues of bias and impartiality and “assumes that a testing procedure exists” (McNamara & Ryan, 2011, p. 165). In other words, a test can be fair but unjust if used as a policy instrument without considering cultural contexts, for example (Deygers, van den Branden, & van Gorp, 2018).

Language assessment literacy (LAL) is another issue currently discussed in the area of language assessment, and it is important for the purpose of this paper since it considers language teachers’ competence in language assessment. With its roots in assessment literacy (Fulcher, 2012; Stiggins, 1995), LAL relates to the skills, knowledge, and practices of assessment that different stakeholders should possess (Taylor, 2009). Inbar-Lourie (2008) maintained that LAL “comprises layers of assessment literacy skills combined with language specific competencies” (p. 389), which implies knowledge about what to assess, why and how-in Stiggins’s (1995) words-anticipating what can go wrong and being able to take actions regarding the type of assessment used. Inbar-Lourie summed up assessment literacy as “the capacity to ask and answer critical questions about the purpose for assessment, about the fitness of the tool being used, about testing conditions, and about what is going to happen on the basis of the results” (p. 389). Malone (2013), for her part, included the classroom context when defining LAL, maintaining: “language assessment literacy refers to stakeholders’ (often with a focus on instructors’) familiarity with measurement practices and the application of this knowledge to classroom practices in general” (p. 330).

With this in mind, I intend to describe how language assessment is addressed in the Colombian context, what the concerns of language teachers and academics in this respect are, and how they are responding to these current global concerns of justice/fairness and LAL. To do so, I have reviewed five Colombian academic journals that specialize in publishing articles in the field of language teaching. I analyzed the publications that dealt with language assessment and testing and found six categories related to the main issues in this area: assessment practices, beliefs about assessment, skills involved, testing, teacher education and development, and language assessment literacy.

Method

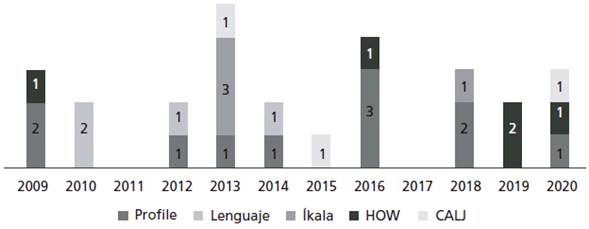

This paper analyzes the articles published between 2009 and 2020 in five Colombian academic journals: Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal (CALJ), HOW, Íkala, Lenguaje, and Profile. All of them, except for HOW, belong to well-known public universities in the country and they cover language teaching. HOW, for its part, is published by ASOCOPI-the Colombian Association of Teachers of English.

For the journals Íkala, Lenguaje, and Profile, I searched using the phrase “language assessment” and “language testing” in the titles and keywords in the EBSCOhost database and limited the search to the above-mentioned period. The results showed 12, 10, and 38 publications, respectively. Using the same filter and phrases, I searched the CALJ webpage directly and obtained 53 results. Then I revised the article abstracts to ensure that the publications had originated in Colombia. For the review of the HOW journal, I searched volume by volume, identifying titles that included “(language) assessment” or “testing,” and then I read the abstracts to ensure that they met the proposed criteria for a final decision. All this resulted in a corpus for this review composed of 29 articles, distributed as shown in Figure 1. I then read the publications and identified common interests which subsequently became the categories that I will introduce later.

An Overview

The discussion by Colombian researchers about language assessment presented higher frequency-yet low if the relevance of assessment in education is considered-in the second third of the 12-year period (between 2013 and 2016), in which all the reviewed journals had at least one related publication. Overall, articles were of two types: those based on research and those derived from the researchers’ reflections. With six articles of reflection, the vast majority were of the first type. These included three articles reporting quantitative studies and two giving an account of mixed-methods studies; the rest of the articles (85%) reported qualitative research. In this large group (12 articles in total), action research (six articles) and case studies (six articles) were the designs explicitly reported. Some of the other qualitative studies were designed as exploratory, others as descriptive, and others as interpretive. Furthermore, there was one article reporting a theoretical analysis. The articles were published in English, except for three that were written in Spanish.

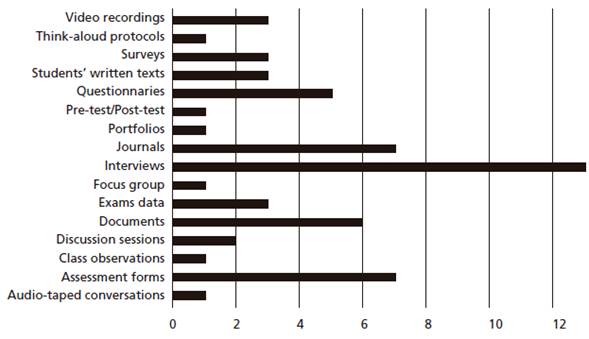

With regard to the methods used to collect information, interviews appeared in first place, followed by journals-written by teachers, students, or researchers-, and assessment forms-that included self- and peer-assessment. Figure 2 shows the wide variety of methods and the frequency with which these were used. Nevertheless, regarding the convenience of having multiple sources of data in qualitative studies as some scholars maintain (Creswell, 2014; Merriam & Tisdell, 2016), a good number of these studies fell short in this aspect. With a range of one to five methods to collect information in the articles under review, one third of the papers reported using two methods, while one fifth reported three methods. Five methods were used in only one of the studies while four studies reported to have used four methods.

The Researchers’ Interests

Scholarly interest in the field of assessment during this period showed considerable variety. I grouped these interests into six categories: assessment practices, beliefs about assessment, skills involved, teacher education and development, testing, and language assessment literacy. I will now discuss each of these and will present a table that summarizes the common findings in each category.

Assessment Practices

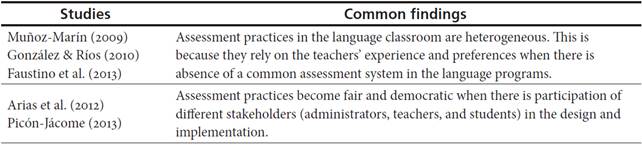

Muñoz-Marín (2009) -in an exploratory study-identified teachers’ assessment practices in the English reading comprehension program at a public university. He found that there “may be as many assessment practices as there are teachers in the programs” (p. 78). One possible reason for this, he said, was that teachers had autonomy in designing their courses, and there was no assessment approach defined by the institution yet. Another finding reported by Muñoz-Marín was that the teachers in the study used quantitative assessments and translated the results into qualitative concepts, as required administratively. This seemed to respond to the teachers’ difficulty to deal with qualitative assessment as well as to the students’ lack of familiarity with it-and their preference for numbers rather than concepts in the assessments. Besides, the author found that the participating teachers were not familiar with alternative assessments, and they felt the need to verify students’ learning through instruments such as tests and quizzes that gave more precise and valid information about their achievement of goals.

González and Ríos (2010), for their part-in a qualitative descriptive study-gave an account of the discourses about instruments and practices of evaluation used by teachers of French in the planning, design, and development of evaluation in a language teaching program at a public university. Similar to Muñoz-Marín (2009), they found that the assessment practices in the French component were “heterogeneous due to the subjectivity of conceptions, beliefs, pedagogical knowledge and experiences and the lack of continuous training” of the teachers, who “followed the institutional regulations strictly” (González & Ríos, 2010, p. 133, translated from Spanish). They also found poor test design and lack of sound assessment tools. Although the authors evidenced an effort to use new assessment practices centered on competences, the main purpose of assessment was still conceived as to classifying, selecting, and punishing in practices in which the teachers’ power prevailed.

Similarly, Faustino et al. (2013) found heterogeneous assessment practices and agreed that it was due to the particular conditions of their institution, a public university; echoing Muñoz-Marín’s (2009) and González and Ríos’s (2010) findings, they explained that this heterogeneity derived from the absence of a common assessment system in their teaching program and the knowledge and experience of the teachers involved. The analysis of the French and English courses syllabi in their language teacher education program revealed the use of both formative and summative assessment, presented as continuous and fixed-point assessment, respectively. There were also indications of alternative assessment-portfolios being the main instrument-and the use of self- and peer-assessment. Nevertheless, Faustino et al. considered that there was more evidence of summative assessment, probably due to institutional requirements. Despite this, the authors highlighted that the participating teachers’ agreement about the final grade came from the weighing of a variety of activities rather than from one single assessment at the end of the course.

Arias et al. (2012) implemented an action-research study focusing on an agreed assessment system in three different foreign language programs. This was closely related to assessment practice and its implications, derived from a prior study that had revealed a lack of coherence between language assessment and student promotion. This system was presented as a means of articulating assessment practices that “allow to reach consensus between teachers and administrators and promote coherence by offering common criteria and the same language about assessment” (Arias et al., 2012, p. 102, translated from Spanish). The assessment system was general, flexible, and it could be adapted to the particularities of different programs, as well as being rigorous and continuous. As a result of the implementation, assessment practices turned into fair and democratic practices that benefited students, teachers, and institutions.

Another topic discussed relating to fair and democratic assessment was the use of rubrics that were agreed upon by both teachers and students. In this respect, Picón-Jácome (2013) -in an article of reflection based on his own pedagogical experience-gave an account of the highly positive impact that involving students in the design of rubrics had. As he explained, not only did it increase the assessment validity and transparency, but also promoted student participation-which turned it into a democratic assessment practice-and ensured formative assessment. The author argued that teachers should use equitable and democratic forms of evaluation and proposed the use of inclusive and democratic rubrics to facilitate students’ learning. Table 1 presents a summary of the common findings in this category of assessment practices.

Beliefs About Assessment

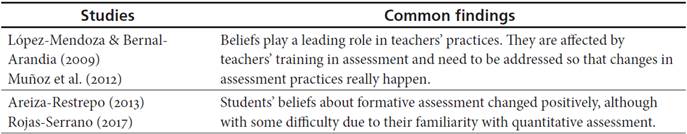

Although fewer articles address the issue of beliefs about assessment, some scholars recognized that they played an important role in teachers’ assessment practices (González & Ríos, 2010; Muñoz-Marín, 2009). López-Mendoza and Bernal-Arandia (2009) -in a qualitative study that examined 82 teachers’ perceptions about language assessment-found that the level of training in language assessment impacted their perception about it. Teachers with no training, the authors concluded, tended to have a negative perception of language assessment or associated assessment to grades and institutional requirements mainly; conversely, teachers who had had formal training in assessment viewed it as a part of teaching and as a tool to promote learning. For this reason-as well as this finding, in the same study, that there was little published research in the field of assessment and few assessment courses offered by universities in both undergraduate and graduate language teaching programs-the authors recommended that teachers should receive training in language assessment before they started teaching the language and advocated for the professionalization of teachers in the field of assessment.

Similarly, Muñoz et al. (2012)-in an empirical research study that aimed to identify the beliefs of a group of 62 teachers about assessment-found that teachers’ beliefs did not match their practice completely. The study revealed that, although the participating teachers considered formative assessment relevant in enhancing their students’ learning, they tended to focus on summative assessment. The authors also argued that in order to change teachers’ assessment practices, their beliefs should be taken into account in the implementation of new assessment systems. In fact, three of the reasons for change in the assessment practices that the participating teachers acknowledged were professional development, self-discovery, and institutional policy. Self-discovery, Muñoz et al. considered, allows teachers to be aware of their beliefs and how their teaching reflects them; as this happens, teachers “will be more able to change their beliefs and practices in a constructive and beneficial way” (p. 155). These scholars focused on the need to strengthen efforts to promote the practice of formative assessment which, in their view, could be accomplished within professional development programs.

Areiza-Restrepo (2013), for his part, carried out a qualitative study to examine students’ views of formative assessment as well as their perceptions of the implementation of this system in their language course. The author found that his students viewed formative assessment as a tool that helped them “become aware of their weaknesses and strengths in their communicative competence and of the situations in which this awareness arose; and thanks to FA [formative assessment] they experienced a sense of achievement because they realized they had learned” (p. 173). Also, with respect to the implementation of the formative assessment system in their class, students perceived this as a transparent process. As a result of this experience, the author called on teachers to involve their students in democratic assessment practices that include their voices in the description of learning outcomes in their course.

In similar fashion, Rojas-Serrano (2017) wanted to know how students who were used to quantitative assessment viewed the qualitative assessment system at an English institute, as well as the perception they had about the alternative assessment activities he gave them. The author found that it took students some time to get used to qualitative assessment; they felt that quantitative assessment was more accurate at the moment of a “non-pass” situation, for example. However, students saw some benefits in the new alternative assessments they were given, such as being able to recognize their strengths and weaknesses-in agreement with Areiza-Restrepo (2013) -, lowering anxiety during assessment, and receiving feedback. In the end, Rojas-Serrano acknowledged that alternative assessment demands a lot of time and energy from the teachers, added to the need to train students in it, but it is worthwhile since this kind of assessment fosters reflection and autonomy, and students do appreciate the benefits.

More recently, Giraldo (2018a) explored the beliefs and practices that a group of 60 English teachers held when designing an achievement test. He found that this group of teachers believed that the designed tests should meet four principles of assessment; these tests should be valid, reliable, authentic, and provide positive washback. Also, the study revealed that the teachers’ practices in the design of the test reflected their beliefs to a great extent. Table 2 summarizes the common findings in this category.

Skills Involved

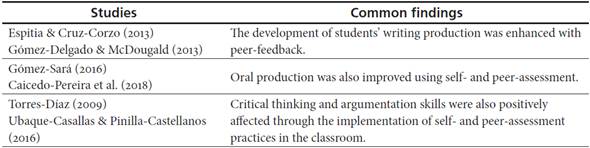

This category represents the topic that Colombian researchers find most interesting in the field of assessment. The studies in this category focus on the use of different assessment forms or tools relating to or aiming at the development of skills such as writing, speaking, critical thinking, and argumentation. In the first case, Espitia and Cruz-Corzo (2013) analyzed the use of peer-feedback to help students improve their writing skills through online interaction. In a case study report, the authors described how students undertook the task of giving online feedback to their peers’ written compositions and how students reacted to such peer-evaluation, helping them to improve their writing skills. Students were involved in the construction of rubrics to assess their peers’ texts and, in doing so, they became aware of what was expected from their own written production. As a result, students’ writing showed linguistic improvement. However, Espitia and Cruz-Corzo found that the students’ beliefs regarding authority in assessment prevented them from giving feedback to their peers more actively. Students believed that it was the teacher’s job and did not consider that their partners’ feedback would be appropriate. Despite this, with their involvement in the construction of rubrics, students showed that they were more willing to accept their peers’ comments.

Similarly, Gómez-Delgado and McDougald (2013) examined the role of peer-feedback in the development of coherence in writing. In an action-research study that involved students’ feedback to their partners’ blog entries, the researchers found that by exchanging feedback through informal writing exercises students improved or maintained coherence-specifically regarding text unity and clarity-in a text. They also found that this practice shaped students’ cognition and affection.

With respect to assessment of oral production, Pineda (2014) reported the experience of a study group with the design and use of a rubric to assess students’ oral performance. The author described the process of designing and training teachers to use a rubric to assess the oral performance of young learners at the beginner level, a process that took at least two years. Findings suggested that, in general, teachers who participated in the study found that the rubric was practical and easy to use, although some of them confirmed that it was difficult to get used to using it. They acknowledged the importance of being trained to use the rubric and also “discovered in the rubric a tool for obtaining evidence of their students’ performance, helping students become aware of their weaknesses and strengths, and making them responsible for their learning needs” (Pineda, 2014, p. 192).

In another study involving speaking, Gómez-Sará (2016) identified the linguistic, affective, and cognitive needs of a group of 14 in-service teachers working at a private school and proposed a strategy that involved peer-assessment and a corpus to address such needs. The pedagogical intervention had two stages: (a) a training stage, in which participants became familiar with the study and with the peer-assessment forms and the corpus, and (b) a main implementation stage, during which the author collected information. Through qualitative analysis of the data, the researcher found that the strategies used in her study (peer-assessment and the corpus) impacted the participants’ oral production positively as they became more willing to improve, used compensatory strategies, and constructed a personalized version of the corpus. Nonetheless, the participating teachers tended to over-depend on the corpus and to under-assess their peers.

The third study related to the assessment of speaking was carried out by Caicedo-Pereira et al. (2018), in which they examined the use of self-assessment to improve the oral production of a group of 27 participants. The researchers looked into the impact of self-assessing recorded videos of IELTS-like oral tasks using an adapted version of the IELTS rubric, and they focused on the assessment of grammar accuracy and grammatical range only. Through both qualitative and quantitative data analysis, the authors found that participants could recognize their flaws and establish a route to improve and overcome their shortcomings. Also, as they were able to become aware of their own improvement after analyzing subsequent videos, their motivation increased noticeably.

The development of critical thinking was another aspect aimed at being fostered through assessment. Torres-Díaz (2009), in a qualitative study at a public school, analyzed the use of portfolios and peer- and self-assessment in order to enhance critical thinking skills in her students. She found that writing portfolios fostered the students’ autonomy since they could explore their interests and set the path to follow in their learning process. In doing this, students were able to reflect on their own progress from a critical perspective, deciding what they needed to improve (self-assessment practice). Also, as students had to read their partners’ portfolios, they made comments on their peers’ work. The researcher found that her students were open to receiving their peers’ feedback and, based on that, they reflected on their own work and took actions to improve it. All in all, Torres-Díaz found that the use of portfolios accompanied by peer- and self-assessment practices helped develop critical thinking skills such as self-examination and self-regulation.

The last in this group of skills involved in assessment focused on developing argumentation skills with the practice of peer-assessment. Ubaque-Casallas and Pinilla-Castellanos (2016) carried out an action-research project to help their students overcome the difficulties in developing their ideas when there was class discussion. The researchers provided students with argumentation outlines and, when it was shown that it was not enough to help them develop their arguments, they incorporated peer-assessment. They concluded that

through the assessment of oral tasks learners created individual knowledge regarding their own argumentation skills and abilities to be used in connection with certain vocabulary. [ The constructed knowledge was] also the result of a collaborative endeavor where peers co-constructed new learning schemas that helped modify the existing ones. (Ubaque-Casallas & Pinilla-Castellanos, 2016, p. 118)

What is more, according to the authors, students’ engagement in peer-assessment of oral performance in class discussions fostered reflection on their own argumentative skills and this resulted in more self-reflective speakers who assumed agency in the development of their arguments when discussing topics in class. The common findings in this category are shown in Table 3.

Testing

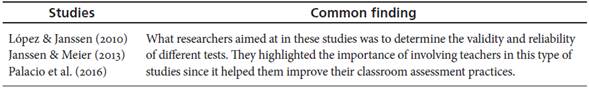

Four papers reported studies that addressed the issue of language testing. In the first one, López and Janssen (2010) examined the ECAES English exam validity. Through content evaluation sessions with 15 university English teachers and think-aloud protocols with 13 university students, the researchers framed a validity argument (in favor and against) from evidence based on the following aspects which emerged as categories in the analysis: interactiveness, impact, construct, and authenticity of the exam under scrutiny. They found that, despite the positive evidence for the validity, negative evidence was stronger to build a case against the validity of the test in the way it was then designed. In their words:

1) general English language proficiency cannot be accurately judged from this test; 2) we cannot make responsible generalizations about the test takers’ English language ability beyond the testing situation; and 3) we cannot make responsible predictions about the test takers’ ability to use the English language in real-life situations. The central problem in the validation argument for the ECAES English Exam in its current form is that it is being used to describe a student’s English language level based on the CEFR. (López & Janssen, 2010, p. 443)

The second paper reported on a quantitative study that aimed to respond whether students had reached the language level required for graduation in a language teaching program. This study was framed within the language teaching program evaluation. Kostina (2012) used the results of the institutional proficiency exam in a six-year period to identify the English level that their students had reached by the end of their program. She found that about half of the students reached the expected B2 level. This proved, according to the author, that it was necessary to take action to help students improve their language proficiency not only at the classroom level, but also at curricular level.

Third in this group was a paper that reported on a quantitative study by Janssen and Meier (2013), who aimed at determining the efficacy of the reading subsection in a placement test for doctoral students. With the use of descriptive statistics, reliability estimates, and measures of item facility and discrimination, the researchers found that this section of the test was highly reliable. Nonetheless, the study revealed that some items, specifically those involving vocabulary and grammar, appeared to be very easy to the test-taker population and the researchers suggested that test developers should create more challenging items of these kinds. Janssen and Meier also addressed the relevance of involving local instructors in continuous test development processes, which could result in sounder assessment practices.

Lastly, Palacio et al. (2016) examined the validity and reliability of tests designed in alignment with an English program for adults in a private university. These were criterion-referenced, discrete-point tests administered at certain moments during the semester. Using the same tools as Janssen and Meier (2013) plus correlational analysis, the researchers found that the developed set of tests were reliable and valid. The validity arguments for these classroom assessments that the researchers created were categorized in terms of content-meeting course standards-, consequences-pass/fail decisions that might delay graduation for students-, and values implications-as designed tests reflected the institutional teaching values. They also found that this involvement of teachers in the design of curriculum-related items for the tests impacted teaching and assessment practices. The common finding in this category is shown in Table 4.

Teacher Education and Development

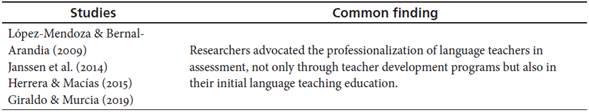

This review showed that the researchers advocated teacher training in assessment or evaluation; the emphasis, however, was on teacher development (targeting in-service teachers) rather than on teacher education (targeting preservice teachers). To start with, López-Mendoza and Bernal-Arandia (2009), in their study to examine teachers’ perception about language assessment, reviewed the curricula of 27 undergraduate and seven graduate language teacher education programs in Colombia. They found that very few of these programs offered training in either educational or language assessment. Because of this finding-and the impact that training in assessment had on teachers’ perceptions (see category Beliefs About Assessment) and, therefore on assessment practices-, the researchers strongly suggested that

all prospective teachers take at least a course in language testing before they start teaching, and should strive to better themselves through in-service training, conferences, workshops and so forth to create a language assessment culture for improvement in language education. (López-Mendoza & Bernal-Arandia, 2009, p. 66)

Janssen et al. (2014) -in an article that exemplified the use of classical testing theory and item response theory-tried to provide language teachers with assessment knowledge that they could use to develop sound classroom assessments. The authors demonstrated the use of these two theories to understand the performance of a placement test. This they did, responding to their belief about promoting assessment literacy and hoping that “program teachers begin to inform themselves from a variety of perspectives about the quality of the instruments they are designing and employing” (Janssen et al., 2014, p. 181) so that the uses teachers make of tests are fair, proper, and valid. Herrera and Macías (2015) advocated teacher development in language assessment calling for the improvement of teachers’ LAL. However, as the key point in this article of reflection was LAL, I decided to group it in the following category.

Also dealing with LAL, but highlighting the professional development of preservice language teachers, Giraldo and Murcia (2019) looked into the impact that a language assessment course had in students of an undergraduate language teaching program. The course first presented students with theory about language assessment and how this was reflected in designed tests. The second part of the course was devoted to the design of items and tasks for language assessment and carried out peer-assessment to improve them. In the last part of the course, students discussed issues related to language assessment in Colombia. The study revealed that the course had great impact on the students’ conceptions of language assessment and provided them with a wide theoretical framework used to design language assessments. Table 5 shows the common finding in this category.

Language Assessment Literacy

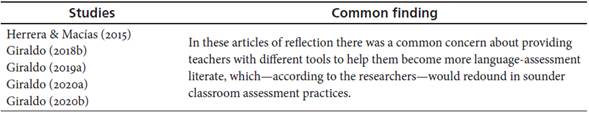

LAL is one of the most recent trends in the discussion about language assessment. In Colombia, based on this journal review, the first researchers to address this topic explicitly were Herrera and Macías (2015). In an article of reflection, the authors attempted to raise awareness of the relevance of LAL and claimed that more preparation and development were necessary. They defined both assessment literacy and LAL, presenting a review of studies in LAL in teacher education, and suggesting what could be included in the knowledge base of LAL based on contributions by different authors. Furthermore, Herrera and Macías recommended a questionnaire-adapted from Fulcher’s (2012) -to diagnose teachers’ LAL needs. This instrument, the authors argued, helped teacher educators to “determine EFL teachers’ current knowledge and awareness of the many aspects that are involved in LAL” (Herrera & Macías, 2015, p. 308). Finally, they claimed that, in teacher education, coursework assessment should be given the same attention as instruction.

Later, Giraldo (2018b) -in another article of reflection-showed how the scope of LAL has expanded to different stakeholders, for example. He also presented a list of LAL contents for language teachers based on his theoretical exploration. The author acknowledged that “this list is not meant to be an authoritative account of what LAL actually is for language teachers” (Giraldo, 2018b, p. 191); instead, he expected that this would serve to stimulate discussion in LAL for language teachers in particular.

Backing up his attempt to raise awareness of the relevance of LAL and its implications in the design of sound assessments, Giraldo (2019a) states that “language assessments can be influenced by three major components: theoretical ideas that apply to language assessments, technical issues that represent professional design, and contextual and institutional policies in which language assessment occurs” (p. 133). In this article of reflection, the author described the central qualities of language assessments and provided guidelines for the design of useful assessments. Also, the author used a sample of a listening exam to prove how the poor design of any assessment can be detrimental. Giraldo closed his reflection by noting that teachers needed to reflect on the assessments they designed and to consider the three components that, in his view, influenced language assessments; in this way teachers would be able to make sound interpretations of their students’ language ability and potentiate their learning.

Giraldo (2019b) also examined the LAL of five Colombian teachers of English through their practices and beliefs regarding assessment. In this qualitative study, the author identified six major categories to describe his participants’ contextual LAL: practices, beliefs, knowledge, skill, principles, and needs. According to the researcher, the study revealed that the participants used both formative and summative assessments in their classrooms; the knowledge that participating teachers reported aligned with what the literature evidenced in terms of validity and methods of assessment. First of all, the teachers reported having affective skills related to assessment-which the author connected to the particularities of the context. Furthermore, feedback was regarded as a principle of language assessment practice in their classrooms. In addition, the author believed that teachers would benefit from more training in language assessment focusing on theoretical and practical issues of testing. Finally, the author claimed that these findings could serve as a baseline for LAL development programs.

In another article of reflection, Giraldo (2020a) discussed the need to expand research methodologies to better understand teachers’ LAL. He proposed adopting the post-positivist and interpretive paradigm to help reveal the complexities of LAL as situated practice. The author described different research constructs in the field as well as different qualitative methodologies that could be used in the further construction of knowledge about teachers’ LAL.

Last in this group, Giraldo (2020b) showed, in a reflection article, how language teachers could benefit from the use of basic statistics to understand test scores in their classrooms. In doing so, the author introduced descriptive statistics-aimed at describing scores and their behavior-, and evaluative statistics-focusing on the determination of test quality. Giraldo, in agreement with Janssen et al. (2014), considered that the use of statistics helped teachers not only to decide on the quality of the tests they use in the classroom, but also to raise their LAL levels which, in the end, would redound in more appropriate assessment practices, better teaching, and, therefore, better learning. Table 6 shows the common finding in this category.

Conclusion and Further Considerations

This review shows that Colombian scholars’ interests in language assessment in the last decade have been varied, as varied are the assessment practices some of them found in their research. Not only is this enriching for the discussion in the field, but it is also necessary to have a more comprehensive understanding of language assessment, its possibilities and implications. With regard to the issues involved in the current global discussion, presented in the introduction of this paper, none of the articles I reviewed addressed the issue of justice in language assessment. There was, however, some interest in addressing the issue of fairness when, for example, some scholars proposed the use of democratic practices of assessment or when the principles of assessment were tackled. LAL, for its part, appeared as an emerging interest in the Colombian language teaching community.

The researchers who addressed the issue of assessment practices found that these varied widely due to lack of training, personal experiences, and absence of an approach established by the teacher education programs. Although this seems to be negative, it sheds light on what needs to be addressed in an attempt to help our teachers carry out sounder assessment practices. Carrying out varied assessments is recommended as long as they are sound practices that respond well to the context where they are developed and result in improving learning.

On the other hand, beliefs have been proved to play an important role in the practices of assessment-on the teachers’ part-and this is why some scholars recommended taking into account teachers’ beliefs so that changes can really happen. The relationship between beliefs, practices, and training is a cycle expected to become virtuous as long as teachers become aware of their practices, reflect on them, identify needs, address them, and modify their beliefs concerning assessment. On the students’ part, beliefs were studied to determine how they experienced particular forms of assessment. This is also helpful in the reflection about practices and identification of needs in the assessment cycle.

Regarding the improvement of language skills, the use of self-assessment and peer-assessment was frequent. Whenever there was explicit reference to peer-assessment, self-assessment appeared to be involved. This shows high scholarly interest in the promotion of alternative assessment to foster students’ autonomy and language learning. We teachers need to make students aware of the benefits of these practices and train them in carrying them out constantly. Despite the fact that some students considered that assessment was a teachers’ job, teachers do not need to check their work all the time to make sure that assessment, in the form of feedback, is correct. If learning goals are clearly stated and students know them, they can track their learning themselves and do the same with their peers.

Scholars were also interested in discussing principles of language assessment and testing. This is indeed relevant. However, it is also important to bring this discussion to the classroom setting and examine more often whether classroom-based assessment meets those principles that need to be adapted to the context.

Finally, there was a common call for training in language assessment in teacher education and development programs. This was strongly linked to the discussion involving LAL. Some scholars ventured to propose what could constitute a knowledge base of LAL, others suggested instruments to establish knowledge and needs of LAL. There were also recommendations to use tools that help teachers understand and take advantage of tests results, and suggestions about research methodologies and constructs to expand the knowledge of LAL for teachers. These, however, were presented mostly in articles of reflection, based on the experience of the author or theoretical reviews. While this is not negative at all, it is necessary to have more empirical-based research that looks into the particularities of contexts, for example. This is an invitation for language teachers to be more attentive to their assessment practices and take notes more systematically on what happens in their classrooms so that more action research, to say the least, allows us to build more knowledge about classroom assessment within the language teacher community.