Introduction

Integrating research with teaching represents a fundamental step toward achieving quality education. In Colombia, the official call to train teachers as researchers was introduced by the General Education Act (Ley General de Educación, 1994). Most recently, the government reinforced this policy through Resolution 18583 (2017), which made research training a legal requirement for all undergraduate teacher education programs in the country.

Taking this measure was only a matter of time. After all, teachers who actively engage in doing research not only accrue significant benefits for their professional development but also contribute to the renovation of the school communities they serve (Castro-Garcés & Martínez-Granada, 2016; Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 1999; Edwards & Burns, 2016; Viáfara & Largo, 2018). Even Lugo-Vásquez (2008), who explored the disadvantages of teachers engaging in research, points to the fact that the adverse effects of teacher research are associated with teachers’ lack of training, time, and administrative support rather than research per se. Albeit its evident benefits, teachers do not learn to do research by themselves: They need to be trained in doing so.

Restrepo-Gómez (2007) felt the need to differentiate between scientific and formative research to pave the way for research education in Colombia. Whereas experienced researchers conduct the former to generate new knowledge and solve perceived social and scientific problems, research educators engage in the latter to educate new researchers the fundamentals of research theory and practice. Miyahira-Arakaki (2009) claims that formative research is an educational tool that promotes students’ appropriation of research knowledge.

Abad and Pineda (2018) state that, within the strand of formative research, student teachers get research training in two different yet complementary ways. The regular path implies taking mandatory research courses leading to the completion of the graduation paper. Those students who want to further their research training also follow the alternative path, which usually implies taking part in a semillero de investigación (research incubator; hereafter, RI).1

Since their inception in the last decade of the 20th century, RIs have become a hallmark of Colombia’s academic landscape. Today, practically all higher education institutions in the country have integrated RIs into their programs to strengthen research training. RIs constitute spaces for personal, professional, and academic growth that allow students to engage in the planning, implementation, and dissemination of formative research while building solid academic communities.

Despite the popularity of RIs, little has been inquired about the pedagogical relationships nurtured within them and how these relationships impact future language teachers’ professional identity as researchers. This paucity of information regarding RIs led us to posit the following questions: What are the essential features that characterize the pedagogical relationships between RI coordinators and students from the English teaching program at Universidad Católica Luis Amigó2? How do these relationships influence the identity construction of preservice teachers concerning their research training? By pursuing this line of inquiry, we sought to analyze the pedagogical relationships between RI coordinators and students in light of the theory of mentoring and their influence on the identity construction of preservice teachers as researchers. Next, we summarize the concepts and theories that guided our research.

Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

Pedagogical Relationship

The pedagogical act (Barajas, 2013; Houssaye, 1988) takes place between the three vertices of a triangle: teacher, learner, and knowledge. The sides of this triangle describe three separate yet intertwined relationships:

The didactic relationship is the relationship between teacher with knowledge and that allows him to teach. The pedagogical relationship is the relationship between the teacher and the student, which allows the process to be formed. The learning relationship is the relationship that the student will build with knowledge in his approach to learning. (Zerraf et al., 2019, p. 2)

For Sánchez-Lima and Labarrete-Sarduy (2015), although the pedagogical relationship between research trainers and trainees originates and develops primarily within institutions, it goes beyond their boundaries, especially as it involves the development of ’not only cognitive but also affective dimensions of the student. Given the implications of research training for the professional development of novel researchers, the relationship between research trainer and trainee cannot be understood as a traditional teacher-student relationship based on the presumption that the teacher should be the sole purveyor of knowledge and the students only passive recipients.

Research Incubators

RIs are groups of “high school or college students who receive research training under the tutelage of a more experienced researcher” (Abad & Pineda, 2018, p. 94). Higher-education institutions often sponsor RIs, which ordinarily constitute learning communities (Sierra-Piedrahita, 2018) that engage in formative research within a particular discipline.

González (2008) claims that, through RIs, institutions pursue the formation of a research culture among undergraduate students, who get together to carry out research training and networking activities. Moreover, he emphasizes that RIs offer a space for the comprehensive development of their members, who thereon learn to design research tools and develop cognitive, social, and methodological skills.

These learning communities play a crucial role in education, as they concern themselves with different disciplines, and their structure guarantees their diversity and continuity; furthermore, the structure of RIs and the pedagogical relationships they favor make them educational settings wherein research training becomes a “perennial” process (García, 2010).

The popularity RIs have gained in Colombia and other Latin American countries may be partially attributed to the fact that they offer teaching and learning conditions that differ from those of regular research courses. RI participants meet beyond the temporal and spatial confines of a traditional class: Students who make up an RI, for example, often remain under the guidance of their coordinators for periods that extend throughout their bachelor’s degrees. Furthermore, their academic progress is established via formative rather than summative assessment. Hence, teaching and learning conditions in RIs facilitate the emergence of research mentoring (Borg, 2006; Mora, 2018).

Mentoring

According to Malderez (2009), mentoring is a “process of one-to-one, workplace-based, contingent and personally appropriate support for the person during their professional acclimatization (or integration), learning, growth, and development” (p. 260). Unlike other teachers of teachers, mentors are models, supporters, sponsors, acculturators, and educators who accompany and guide novice teachers in the process of integration and inclusion into a particular professional milieu (Malderez, 2009).

Along those lines, Dağ and Sari (2017) claim that:

The mentor has a series of roles such as a parent figure, problem solver, builder, recommendation giver, supporter, educational model, coach or guide. In addition, they are required to struggle with the ways of thinking of the mentees to improve their self-competences and to prepare them to the actual world of education. In this context, mentoring is a multi-dimensional process involving emotional support and professional socialization in addition to pedagogic guidance. (p. 117)

The benefits and challenges of mentoring in research education have been explored across multiple disciplines (Brown et al., 2009; Byars-Winston et al., 2020; Gholam, 2018; Gruber et al., 2020). In the field of language teaching, some researchers (Borg, 2006; Delany, 2012; Mora, 2018) conclude that a fundamental condition for teachers to be successfully trained as researchers is the assistance of a mentor. In a shared reflection on their mentoring experience in an RI, Abad and Pineda (2018) sustain that “research training galvanized by mentoring has an enormous potential to further teachers’ professional development [and] bridge existing gaps between educational theory and teaching practice” (p. 85).

Teacher Identity

Besides being bound to context and shaped by discourse, teacher identity is diverse and fluid, and it is wrought out of the tensions between teachers’ self-perception and the way they are perceived by others (Lu & Curwood, 2015; Pennington & Richards, 2016; Salinas & Ayala, 2018; Torres-Rocha, 2017). Teacher identity could be explained as a teacher’s self-concept portrayed through a continually (re)constructed narrative of who they are, who they want to be, and what their story has been concerning others (Kumazawa, 2013; Varghese et al., 2005; Wang & Lin, 2014). About the multifarious nature of teacher identity, Abad (2021) contends that “teachers’ multiple identities, which come from relational contexts other than school, influence the way they teach and construct themselves as teachers” (p. 124).

Method

Our journey to investigate RIs in the field of language teacher education started in 2016. Initial explorations developed into two research phases. The first empirical study, carried out in 2018, involved the systematization of 51 RIs from different schools at Luis Amigó. The second study included interviews and focus groups with RI teachers and students from the university’s English teaching program. However, information gathered during these two studies aided in constructing the theory of pedagogical relationships we later describe; only data from the second one is presented in this article.

Research Philosophy and Methodology

Subscribing to the interpretive paradigm, we conducted a case study for the second phase of our inquiry. Teacher researchers who investigate from an interpretive perspective try to understand a social reality that is never neutral but relative to the meanings, perceptions, and interpretations that subjects build in their interactions with others and that make complete sense only within the culture that defines the educational phenomenon under study (Pérez-Serrano, 1994; Taylor & Medina, 2013). Through a case study, researchers seek a deep understanding of a complex phenomenon, problem, or program by analyzing specific aspects of a representative unit (a case) within an authentic context (Creswell, 2014; Stake, 1995; Yin, 2013).

Case Binding

For Moore et al. (2012), a case involves “a particular example or instance from a class or group of events, issues, or programs, and how people interact with components of this phenomenon” (p. 244). Although there is no single way to bind a case, we decided to do it in terms of activity, context, and time (Creswell, 2014; Stake, 1995). Hence, our study focused on exploring the pedagogical relationships between teachers, alumni, and students who had engaged in formative research within the context of the RIs belonging to the English teaching program at Luis Amigó. Data were collected during the 2018-2019 academic cycle.

RIs have become a key component of research education within the program. When the study began, it had eight RIs with about 90 students. In addition to the sensitization RI, which marked the initial stage of the research-training process, there were seven other thematic RIs.

Faculty teacher researchers coordinated these RIs, which comprised groups of four to ten students. They met their coordinator at least once a week during two-hour sessions, which could be extended as needed. Additionally, students were part of RIs for periods ranging from one year to the entire duration of their studies, even after graduation.

RI coordinators generally guided students through designing and implementing research projects related to their area of interest. This guidance included training activities that covered the entire length of a research project, from its inception to its dissemination through oral and written media. Consequently, these RIs constituted primary groups of a collaborative nature wherein coordinators had the chance to become research mentors for their students.

Nevertheless, the pedagogical conditions that frame mentorship were absent in only some of the RIs. Further, towards the end of 2019, they underwent a severe crisis, and five were closed down. Reasons for their termination included coordinators’ burnout and failure to meet the university’s administrative and productivity requirements. This crisis points to conflicting views between university research officials and research educators as regards the purposes of RIs and the roles of RI coordinators.

Participants

Participants were selected through criterion-based sampling (Patton, 2001): All had to be teachers, students, or alumni of the English teaching program at Luis Amigó. Coordinators must have performed this role for at least two consecutive years in the same RI. Students must have participated in the same RI for at least one year under the guidance of the same coordinator. In the end, four coordinators and eight students from five different RIs joined the project by signing consent forms. The four coordinators led RIs in assessment, technology integration, language policy, and cultural studies. Their experience as teacher educators ranged between five and 15 years; they all held ’master’s degrees in education or language teaching. Table 1 shows the students’ membership to the five RIs included in the study.

Table 1 Student Participants’ Membership to Research Incubators

| Student code | Research incubator focus | ||||

| Assessment | Technology integration | Language policy | Cultural studies | English in early childhood | |

| Student 1 | x | ||||

| Student 2 | x | ||||

| Student 3 | x | ||||

| Student 4 | x | ||||

| Student 5 | x | ||||

| Student 6* | x | ||||

| Student 7* | x | ||||

| Student 8* | x | ||||

Note. * Alumni

Data Collection and Analysis

We designed interviews and focus group guides considering our experience with RIs and the theoretical framework presented above. We piloted and field-tested each instrument before its implementation. First, we conducted 30- to 60-minute interviews with the four coordinators during the second semester of 2018. The initial analysis helped clarify the coordinators’ perception of the pedagogical relationships they had built with students and their formative roles in RIs. Given the iterative nature of qualitative research, the initial findings derived from the interviews drove the construction of the guides used for the focus groups, which were held the following year and lasted about an hour each. The first focus group included three students; the second one was done with five.

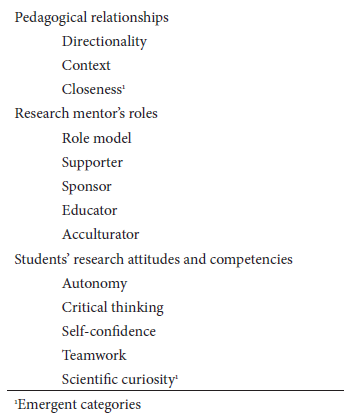

For data analysis, we followed an integrated approach (Curry, 2015). We used a structure of pre-set categories based on the mentoring theory in research education. During the analysis, new categories emerged that were integrated into the category tree. Descriptive and interpretive memos allowed for the consolidation of findings, which were built around the research categories and shared with participants and other academic community members for members checking (Moore et al., 2012). Time and investigator triangulation (Burns, 1999) further enhanced the trustworthiness and validity of the study. Figure 1 shows our category structure.

Findings

Pedagogical Relationships in RIs: Horizontality and Closeness

In referring to the pedagogical relationships they had built in RIs, participants described a training field characterized by horizontality, emotional closeness, and trust among students and between them and the teacher. On this matter, some students commented:

Well, in my case, if I am going to be with this coordinator, it is because I admire them. I very much respect their work and career, so I would say that my admiration [I have for them] has contributed emotionally, always encouraging me always to go beyond [what is required].3 (Student 2, Focus Group 1)

The relationship that I have with my RI coordinator is based on trust; in pedagogical terms . . . I have the confidence to tell them what I like and what I don’t like. (Student 1, Focus Group 1)

This sense of closeness was enhanced by the trust the coordinators bestowed on the students so they could pursue their interests and ask questions and the degree of care coordinators showed for them as valuable team members. On this matter, teachers commented:

I am also a peer; I am not the expert; I feel I have become an expert with them; it is with them that I learn. (Teacher 2, Interview)

In the RI, we create friendship ties . . . we share not only academic but also emotional matters, so we get to know each other’s difficulties, passions, and emotions. (Teacher 1, Interview)

Regarding the pedagogical relationship with the RI coordinators, some students also said:

I believe that asking questions breaks the verticality often established in student-teacher relationships. In this case, the coordinator lets us look for the answers to those questions that even we can propose in our sessions. (Student 6, Focus Group 2)

When you feel important, the bond becomes much more robust. You know that the other person cares and that, in a certain way, you are in a condition of equality with the other because equality means that everyone is important in building knowledge. (Student 6, Focus Group 2)

Besides creating a strong connection with the RI coordinators, students built strong bonds among themselves in a relationship characterized by solidarity and camaraderie that redefined their academic identity in the group. In this regard, some students went as far as defining the RI as a family and even a “pack”:

Amid these investigative dynamics [arises] a sense of solidarity, of being with the other, of even taking responsibility for the other to fulfill the goals we have set for ourselves, that we all have agreed upon. (Student 8, Focus Group 2)

I could say that the [RI] also becomes like a family. (Student 8, Focus Group 2)

The concept of a pack4 comes to mind because, in some way, [the RI] allows you to feel part and have the support of a group, so I feel I belong there, and that feeling is good. (Student 7, Focus Group 2)

The possibility of creating strong bonds around research profoundly contributes to the person’s education, as it taps into their emotional dimension. As some participants indicate, that sense of belonging was brought about and sustained by a significant distribution of power and a heightened sense of reciprocal care within the group. In that regard, some participants remarked:

I think doing research together has been one of the most memorable things I would take from my RI since I have learned from it, and it has touched me at a personal or human level. (Student 6, Focus Group 2)

This possibility of dialogue has brought us so close. Undoubtedly, all this time, we have built a sense of solidarity, a bond of brotherhood through a dynamic of horizontality. (Student 6, Focus Group 2)

Students’ Identity as Researchers: Attitudes and Competencies

The pedagogical relationship students built with their RI coordinators impacted their research attitudes and competencies and, ultimately, how they perceived themselves as researchers in the making. The data show that thanks to their involvement in RIs, students developed competencies and attitudes necessary for research (Pirela de Faría & Prieto de Alizo, 2006), both human and academic. Students emphasized qualities such as autonomy, critical thinking, self-confidence, teamwork, and scientific curiosity. Table 2 includes excerpts that evidence each of these competencies and attitudes described by the students.

Table 2 Research Attitudes and Competences Fostered in Research Incubators

Furtherance of Disciplinary Knowledge

In the RIs, students delved deeper into specific pedagogical or disciplinary aspects of their field; this way, they recognized possible teaching components or research lines to continue advancing their development as teacher researchers. Student teachers indicated that the knowledge acquired within RIs carried over to their teaching. One of the participants, whose RI focused on linguistic policy, stated:

After participating in the RI, I acquired a lens through which I could see the English class and analyze how it is connected to the power games and the national and international policies in education; that is very interesting to see, even in my teaching practicum. (Student 4, Focus Group 1)

Therefore, by a principle of knowledge transference (Cornell-Pereira, 2019), the knowledge, attitudes, and competencies developed in RIs contributed to the training of students not only as researchers but also as teachers.

As teachers in our pedagogical practicum…when we ask ourselves what our next research project is going to be, we ask ourselves not only about the transformation of ourselves as teachers but also about how that transformation also gives us [power] to transform our micro contexts and even much broader contexts. (Student 6, Focus Group 2)

Coordinators as Research Mentors

The coordinators played the roles of educators, sponsors, supporters, and guides as they dealt with their students’ academic training and emotional development. In turn, the students improved their attitudes and honed the competencies required for research. In other words, the roles played by the RI coordinators appear to be directly linked to the attitudes and competencies later developed by their students. In describing the role of their RI coordinator as a sponsor and supporter, one student stated:

The work [we do], I feel, is more mutual. In addition, the coordinator has always motivated us and made us feel more confident, saying, “guys, what you are investigating is fine; keep doing it, and do not doubt yourselves.” So, that also aids motivates us to continue growing. (Student 1, Focus Group 1)

Students also saw their coordinators as guides who scaffolded their learning to do research and to become researchers. One student said: “I see my RI coordinator as a guide and a complete company” (Student 1, Focus Group 1). For students, their coordinators operating as emotional sponsors and academic supporters were vital in developing attitudes such as autonomy and confidence. On this matter, one student commented:

If a person with a professional track record, who knows, tells me that they trust me and believe in me, then why shouldn’t I do it myself? So, they have given me much security and have made me develop more self-confidence as a person. (Student 1, Focus Group 1)

Discussion: A Theoretical Model for Pedagogical Relationships

As pointed out earlier, our initial reflections on the pedagogical nature (i.e., the essential features) of RIs were later supplemented by the findings of two studies, the latter of which we have herein synthesized. Ultimately, this line of inquiry led us to develop a theoretical model about pedagogical relationships in research education that has helped us understand why RIs offer unique conditions for the comprehensive training of new teacher researchers. In the following paragraphs, we outline this model.

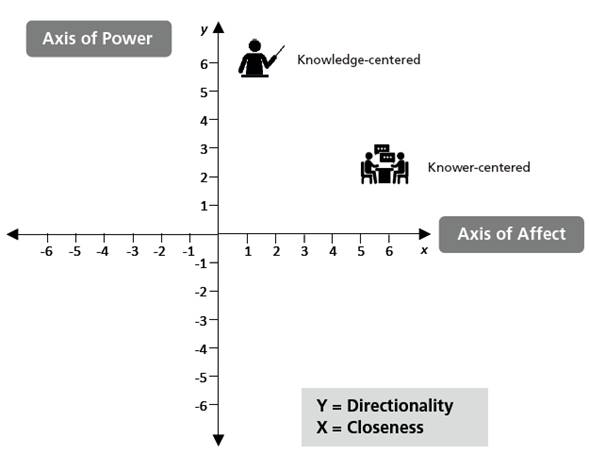

Built around the pedagogical act, every teacher-student relationship emerges from and, at the same time, configures a relational context. This context, which refers not so much to the physical space shared by classroom participants as to the symbolic network of meanings they create, is defined around two axes: the axis of power and the axis of affect, on which directionality and closeness are signaled.

Marked on the axis of power, directionality is defined by the circulation of knowledge and the decision-making process that ultimately frames the curriculum, which the teacher could impose upon or negotiate with students to varying degrees. On the other hand, closeness shows the degree of emotional connection and affinity between teacher and students, which is marked on the axis of affect. The coordinates of power and affect, defined by the degree of emotional closeness between teacher and students and the directionality in which knowledge flows in their interactions, determine the nature of their pedagogical relationship to a large extent.

A traditional pedagogical relationship in a knowledge-centered environment usually implies a considerable social distance between teachers and students. Furthermore, in educational settings where directionality is high and emotional closeness is low, instructors ordinarily focus on deciding what must be learned and how, yet they often disregard students’ emotional response to learning the subject they teach. Such relational dynamics tend to reproduce the banking model of education (Freire, 1968/2005), in which teachers are the sole suppliers of knowledge while students are its passive and often disillusioned recipients. In research education, this form of relationship leads research trainers to overemphasize their roles as transmitters of knowledge and overseers of method application, usually at the expense of their connection with their trainees, which is pivotal in helping them overcome emotional crises associated with their initial inability to take ownership of research as an integral component of their professional identity.

On the other hand, empirical research’s organic and messy nature, when carried out in relatively small yet lasting learning communities (Coll, 2004; Sierra-Piedrahita, 2018), offers different pedagogical possibilities that promote the emergence of research mentoring. In contrast to traditional pedagogical relationships, mentoring involves positive reciprocal affect and distributed power regarding knowledge construction. Hence, mentors and mentees often generate a more dialogic educational context in which knowledge flows in multiple directions.

Learning communities such as those formed in RIs lend themselves to the emergence of research mentoring. As described earlier, pedagogical conditions in RIs are not limited by the traditional space, time, and curricular constraints of regular research courses. As a result, the dynamics between students and teachers drastically shift, primarily as they pursue the resolution of real research problems for which everyone must contribute a piece of the solution. Consequently, as suggested by the results, RI coordinators and students can more easily engage in research mentoring than research trainers and trainees in traditionally organized classroom settings.

Collective approaches to formative research (Hakkarainen et al., 2016), such as those present in RIs, appear to support research mentoring. A caveat, nonetheless, is necessary for a balanced understanding of pedagogical relationships in research education: Research mentoring is neither an exclusive prerogative nor an unequivocal outcome of RIs. Despite their potential as an alternative form of research education, RIs face challenges usually associated with coordinators’ lack of knowledge, time, administrative support, or emotional disposition to engage in mentoring. Likewise, effective research mentoring can also surface in other types of research training, including regular research courses.

RIs often promote collaborative, experiential learning around distributed decision-making regarding curriculum construction and implementation rather than focusing on the transmission and reproduction of theoretical or methodological knowledge. Along those lines, Mesa-Villa et al. (2020) conclude that:

Research Seedbeds comprises [sic] a strategy that fosters a community-based research education approach in which local and situated research practices are favored. This strategy is contrary to traditional educational methods in which research is taught from prescriptive agendas and conceived as an individual set of skills. (p. 171)

Nevertheless, we must note that although differential elements such as small class sizes and flexible temporal-spatial conditions for teaching and learning in RIs are advantageous for forming democratic pedagogical relationships, using them as the single explanation for effective research mentoring would be an oversimplification. Qualities of collaborative approaches to research training, including the communal nature of learning directed towards solving real-life problems, the precedence of integrative over compartmentalized and formative over summative assessment, the diffused and overlapping boundaries concerning traditional teacher and students’ roles, and the distribution of power as regards the multidirectional circulation of knowledge, should be carefully considered in the analysis of pedagogical relationships.

These elements point towards a fundamental epistemological shift in research education from individualistic models centered on knowledge as an external cultural product to collective models centered on knowers as they actively engage in the act of knowing together. Figure 2 summarizes our model and shows the axes of power and affect and the coordinates on which the pedagogical relationships of research trainers and trainees could be located for both knowledge-centered and knower-centered approaches.

Our model, therefore, points to a shift in focus (a) from knowledge (what to know) to knowing (how knowledge is developed), (b) from individualistic approaches that accentuate fixed teaching and learning roles to collaborative approaches that integrate knowers as they fluidly engage in the process of knowledge construction, and (c) from vertical (more top-down) to horizontal (more bottom-up and collegial) relationships between the two human poles of the pedagogical act. Table 3 describes aspects of directionality, decision-making, closeness, and interactional focus5 in each type of relationship. However, it is worth noting that rather than representing a black-or-white dichotomy between approaches, this model is intended to conceptually set the outer limits of a continuum in which pedagogical relationships could be described in their actual fluctuations and emphases.

Table 3 Common Features of Approaches to Pedagogical Relationships in Research Training

| Knowledge-centered | Knower-centered | |

|---|---|---|

| Directionality | + unidirectional | + bi/multidirectional |

| Decision making | + vertical | + horizontal |

| Emotional closeness | - closeness | + closeness |

| Interactional focus | + individualistic | + collaborative |

Conclusions

Being this a qualitative case study, we do not purport to make broad generalizations as researchers in the quantitative tradition would. Instead, we sought to analyze the pedagogical relationships within RIs so that other members of the academic community may recognize our findings as legitimate within our particular context and our theoretical model relatable should they be paired with educational conditions similar to the ones described herein.

That said, as relatively small, yet long-standing learning communities, RIs appear to foster a learning environment of horizontality and closeness among their members. As regards the distribution of power, formative research within RIs usually involves a democratic process in which students not only express their opinion but also contribute to the construction of knowledge. Concerning affect, closeness in RIs, which could be partially attributed to some level of identification of the student with the teacher, is built upon reciprocal feelings of admiration, respect, affection, and trust. These feelings are fundamental for building a teacher-student relationship that sets the stage for research mentoring.

Emotional closeness and distributed power in the construction of knowledge are concomitant to the emergence of mentoring. RI coordinators who effectively assume the role of research mentors become supporters, acculturators, sponsors, educators, and role models for their students (Díaz-Maggioli, 2014; Malderez, 2009; Malderez & Bodóczky, 1999).

The pedagogical conditions of RIs are conducive to the rise of mentoring relationships because they give teachers an exceptional opportunity to connect with students emotionally and engage with them in the actual endeavor of conducting real research exercises that seek to answer genuine problems. Moreover, research mentoring favors the development of crucial research attitudes and competencies such as autonomy, critical thinking, self-confidence, teamwork, and scientific curiosity, which cut across students’ education and contribute to their identity construction as teacher researchers.

The aforementioned pedagogical conditions allow RI coordinators to relate with students academically and personally to better prepare them for the ups and downs of their professional lives as teachers and researchers. Such a mind frame is based on the notion of research training as a journey in which students acquire theoretical and research-based knowledge and experiential and relational knowledge fundamental to their personal and professional development. In summary, coordinators scaffold students to develop research attitudes and competencies during the training process, making students grow as professionals and human beings.

Sustained research mentoring also allows student teachers to deepen the disciplinary aspects of the profession. Hence, by a principle of knowledge transference (Cornell-Pereira, 2019; Gholam, 2018), preservice teacher researchers carry research attitudes and competencies honed in their RIs into other educational settings. Moreover, as Molineros-Gallón (2009) indicated, students taking part in RIs will likely end up guiding research training processes themselves, a vital step towards ensuring a generational renewal in language teacher education.

Finally, teaching and learning in RIs occur in an environment that facilitates students’ personalized training, active participation, and integration with the entire community around the different elements of research. Compared with more traditional approaches to formative research, these conditions stimulate student-teacher relationships of greater personal closeness and better democratic decision-making regarding knowledge construction.

Our analysis resulted in constructing a model that describes pedagogical relationships in research education and points to differences between knowledge-centered and knower-centered approaches to research training. However, the substantial elements of this model about how pedagogical relationships influence teachers’ and students’ relationship with knowledge escaped the scope of the presented empirical research, so they should be further explored and tested in future research projects. In addition, we believe that research mentoring in settings other than RIs and factors leading to the dissolution of RIs well deserve to be investigated.

To conclude, we believe that RIs have become an essential component of research education in our country. When research mentoring consolidates in RIs, students explore research paths within their discipline. At the same time, they grow into active members of a learning community that favors meaningful academic and personal relationships. As students become conscious of the role of research in enhancing the quality of education, they develop research attitudes and competencies that can transform their teaching practice. Ultimately, the heightened awareness they gain about the role of research in language teaching lays the foundations for the solid construction of their professional identity as language teacher researchers.