Introduction

In Mexico, as elsewhere, higher education English teaching professors construct and negotiate their professional paths in complex landscapes where they have to deal with several tensions, such as the one between individual and collective work, especially in their authorship development (Domínguez-Gaona et al., 2015; Encinas-Prudencio et al., 2019; Trujeque-Moreno et al., 2015). On the one hand, policies of organizations such as the Sistema Nacional de Investigadores (National Research System) and formal graduate programs require individual academic production. On the other hand, policies from the Secretary of Education-such as Redes y Cuerpos Académicos (networks and research groups)-and institutions call for collaborative work. This last policy’s main objective is to promote professors’ participation in formal research groups in national and international collaboration and networks and in international publications. However, faculty participation in international academic contexts depends not only on “professional knowledge.” Professors must keep abreast with their current research issues and participate in national and international “conversations” to contribute to the discipline. It certainly requires the capability of collaborating and networking with other scholars. Besides the everyday tensions among participants in professional communities, academics must collaborate and network with scholars from different cultures, who speak different languages, and hold different ideologies (Leite & Pinho, 2017).

Each academic community has its history, culture, and practices. Thus, the implementation of Mexican higher education policies varies depending on each disciplinary culture. In the English language teaching (ELT) community, which is teaching-oriented and relatively new compared to other communities, master’s programs for English teachers were implemented in the 90s. Since the end of that decade, several professors have obtained scholarships for national and international PhD programs. Most of these professors returned to their universities and, in many cases, participated in launching ELT undergraduate programs and other graduate programs. There are 180 undergraduate and 12 graduate programs in ELT or related fields, such as applied linguistics (ANUIES, n.d.). Several alumni from these programs work in different public higher education institutions, as is the case of the participants in this study.

Research on networking practices emerged in the mid-1980s in all kinds of organizations (Ibarra, 2004; Ibarra et al., 2005). About two decades later, interest in collaboration and networking research arose in primary and secondary education (Bogattia & Foster, 2003, as cited in Muijs et al., 2011). More recent studies-such as Fernández-Olaskoaga et al. (2014) on teacher collaboration in virtual settings, Vangrieken et al.’s (2015) review on teacher collaboration, and Krichesky and Murillo’s (2018) study on teacher collaboration-explore this practice in education as a tool for improvement.

Interest in the evaluation of these issues in higher education increased after 2000 (among others, Allen, 2014; Gewerc-Barujel et al., 2014; Kiss, 2020), and various studies raise questions on North and South collaboration and networking (Leite & Pinho, 2017; Thomas-Ruzic & Encinas-Prudencio, 2015). Collaboration and networking have also been discussed in studies related to publication in English in the social sciences and the hard sciences. Curry and Lillis (2010), in a longitudinal “text-ethnographic” study, explored how 50 psychology and education scholars in southern and central Europe published in English. Their findings suggested that solid and long-lasting networks enabled scholars’ publications in English. Englander (2013) discusses the relevant role of collaboration, teams, and networks in a publication in English on the hard sciences. There are, to our knowledge, studies on PhD students’ paths to authorship in the hard sciences (Carrasco & Kent-Serna, 2011; Carrasco et al., 2012; Müller, 2012). However, there seems to be little research in the social sciences on ELT scholars’ collaboration and networking practices in their paths to professional development.

Thus, this study focused on exploring four Mexican ELT professionals’ collaboration and networking practices ten years after graduating from an MA program at a public university in central Mexico. Therefore, the research questions that guided this study were:

1. How are these teacher-researchers’ collaboration and networking practices characterized?

In what kinds of activities do these participants collaborate and network?

To what extent or level?

What kinds of roles do they take?

2. How do the participants’ agencies interplay with their collaboration and networking practices in their professional paths?

Literature Review

Collaboration and Networking in Academia

It was vital for this study to provide an approximation of each term in order to identify collaboration and networking practices. However, in this comparison and contrast analysis, we found that some authors use these terms indistinctly, and meanings vary according to the context in which they are used. For example, some authors view collaboration as collectively working on the same task and towards the same goal (Leite & Pinho, 2017; Müller, 2012), whereas networking is regarded as establishing key relationships or ties that strengthen social capital and career success in academia (Domínguez-Gaona et al., 2015; Leite & Pinho, 2017; Ramírez-Montoya, 2012; Šadl, 2009; Streeter, 2014). In some cases, close relationships are created through networks in both formal and informal contexts (Curry & Lillis, 2014; Ely et al., 2011; Zappa-Hollman & Duff, 2014). Fernández-Olaskoaga et al. (2014), Vangrieken et al. (2015), and Krichesky and Murillo (2018) approach teacher collaboration as a way the individual works with others to form teams to achieve something. Moreover, different interactions seem to happen while collaborating and networking with community of practice members, mainly on-site or virtual, locally, nationally, or globally (Leite & Pinho, 2017). Those interactions occur with peers that share similar roles or with other community members with lower or higher hierarchies (Thagard, 1997). For other authors, collaboration entails establishing a network; networking itself seems to be used to “cultivate your sponsors” (Streeter, 2014) through a web of connections that would lead to innovations in academia (Curry & Lillis, 2010; Leite & Pinho, 2017; Šadl, 2009). Nevertheless, both collaboration and networking bring out other difficulties, such as the complex task of negotiating and finding effective ways to connect and keep those connections active. Table 1 compares the key differences between these two concepts.

Table 1 Collaboration and Networking Practices in Academia

| Purpose | Context | References | |

| Collaboration |

|

Formal ties | Fernández-Olaskoaga et al., 2014; Krichesky & Murillo, 2018; Leite & Pinho, 2017; Müller, 2012; Vangrieken et al., 2015 |

| Networking |

|

Formal and informal ties | Curry & Lillis, 2014; Domínguez-Gaona et al., 2015; Ely et al., 2011; Leite & Pinho, 2017; Ramírez-Montoya, 2012; Šadl, 2009; Streeter, 2014; Zappa-Hollman & Duff, 2014 |

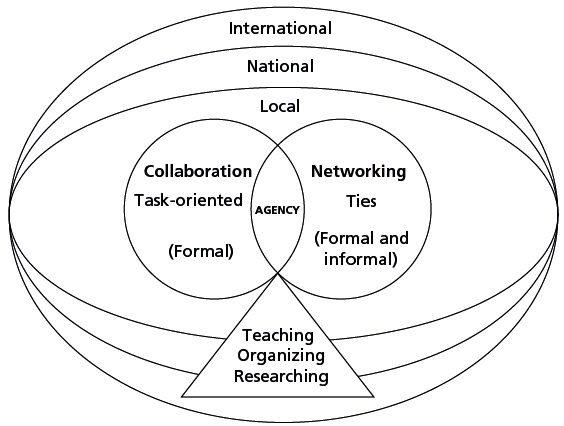

Both collaboration and networking participants’ practices or dynamics occur within three major activities that lead to ELT professional development in the Mexican higher education context: teaching, researching, and participating in professional organizations. These categories, identified by Trujeque-Moreno et al. (2015) and Encinas-Prudencio et al. (2019), are used in this study to examine collaboration and networking practices (see Figure 1) from these participants’ professional paths.

Maps were developed to visualize participants’ practices, the communities they belonged to, and the level at which they participated in their local, national, or international contexts, taking into account the conceptual differences in collaboration and networking above, as well as the participants’ landscape of practice.

In this study, ELT teacher-researchers collaboration and networking practices are explored through a social perspective where relationships are crucial to understanding human and organizational behavior (Muijs et al., 2011). Moreover, learning in the profession is viewed as a socio-cultural process within landscapes of practice (Wenger, 1998; Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015).

The “landscape of practice” of these ELT professionals is a complex system of communities of practice and boundaries between them that have turned, in some cases, into hybrid multidisciplinary communities. Like most other professionals, these professionals participate in more than one research community and learn from their practice in their workplace, professional and social networks, informal communities, and research websites, among others. Professionals inhabit the “landscape” with an identity in dynamic construction and, in the process, often use an amalgamation of resources to construct their professional paths (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015).

In academic communities, participants adopt different roles in their interactions with other colleagues depending on their professional level and type of participation. Some focus more on writing and publication processes and are defined as “literacy” brokers (Curry & Lillis, 2010). They become editors, reviewers, academic peers, English-speaking friends, and colleagues who mediate text production. A few become “network” brokers and promote and facilitate their colleagues’ or students’ participation in their professional communities through their web of connections.

Agency in Professional Paths

When looking at ELT teacher-researchers’ paths (Encinas-Prudencio et al., 2019), two of the critical features of professors’ participation in the community arose: (a) teacher-researchers collaboration and networking practices and (b) agency, which are commonly considered as social action attained by a person’s capacity. Priestley et al. (2012) view agency as an emergent phenomenon. They adopt an ecological view in which individuals achieve agency in specific situations due to their engagement in a specific context. Accordingly, individual capacity and the characteristics and dimensions of the context shape agency as a temporal process.

One of the central arguments in the ecological view of agency is that an individual’s capacity is never enough to achieve agency. Agency is always achieved in concrete contexts, which are formed and shaped by culture (Archer, 2000). Emirbayer and Mische (1998) state that agency can be understood as a temporal process of social engagement permeated by the individuals’ background, projections of the future, and engagement with the present. Through reflexivity-a self-dialogue-individuals evaluate their backgrounds, foresee the future, analyze the present, make strategic decisions, and devise a new action or response to a specific situation. We use this perspective of agency in this study.

Method

This multiple case study was a follow-up study on paths toward authorship in ELT (Encinas-Prudencio et al., 2019). Four categories emerged from the previous study: (a) context awareness of higher education and ELT communities, (b) collaboration and networking, (c) publication practices, and (d) agency. The current study explores collaboration and networking in depth.

Case study research is used to illuminate an understanding of complex phenomena (Merriam, 2009; Stake, 2006; Yin, 2013). Merriam (2009) defines a case study as “an in-depth description and analysis of a bounded system” (p. 40). In this case, we explored four ELT professionals’ collaboration and networking practices in their professional development paths.

We chose the four Mexican participants with more outstanding track records out of eight participants from the previous study (mentioned above): Juan, Joaquín, Verónica, and Graciela (pseudonyms). The primary purpose was to understand the participants’ relationships between their collaboration, networking practices, and professional development. They all graduated from one of two MA cohorts (2005-2007 or 2007-2009) of an ELT program in a public university in central Mexico. Two participants held a PhD, one was about to graduate, and the other seemed not interested in a PhD program since she was more focused on her teaching and research. Although the three PhD programs they studied were very demanding, only one had a scholarship; the other two worked while studying their program.

Over 24 months, we designed and applied the data collection strategies and analyzed the data for this study. Three data collection strategies were used: (a) the participants’ curriculum vitae (CV), (b) interviews based on their CV about their professional development paths, and (c) a final interview where we showed each participant a map of their collaboration and networking practices drawn with data collected with the CV and the first interviews. The main objective of these last interviews was to understand their collaboration and networking practices in teaching, organization, and research and how these related to their professional development.

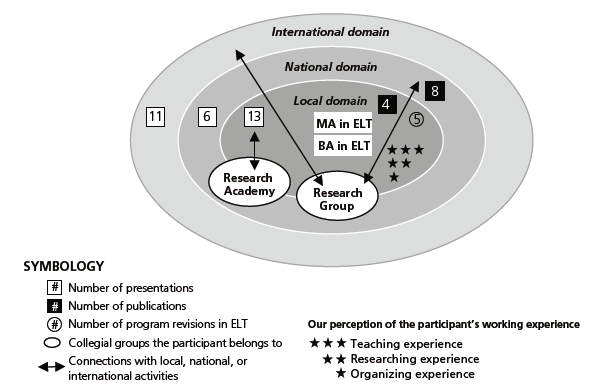

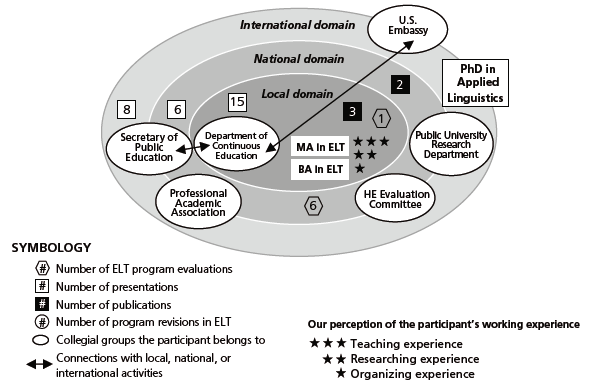

The three of us analyzed the participants’ updated CVs and designed an interview about their professional development paths based on those CVs. With these data and the interview, we engaged in collaborative coding (Smagorinsky, 2008) by comparing and contrasting each of our summaries to define categories. We later drew maps of the participants’ collaboration and networking practices at local, national, and international levels. Later, as mentioned before, each participant was shown their map and then asked for opinions about it. Finally, we redrew the maps with their opinions, as shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Findings

Participants’ Background

All the participants had, we could say, more or less similar education experiences: They all mainly had a public education, learning English in the BA program (only one lived in the USA for two years), and all graduated from the same BA and MA programs. Moreover, they all had full-time positions at a public university in Mexico. Three of them were first-generation students, meaning they were the first children in the family to study higher education. Table 2 illustrates the participants’ educational features.

Teaching, Researching, and Organizing as Leading Activities in Collaboration and Networking in ELT

The results showed that although the participants had all been involved in the three types of activities (teaching, researching, and organization), their levels and kinds of participation varied in some cases significantly. As shown in Table 3, all the participants were immersed in teaching and had between ten and 20 years of experience. They all participated in teaching-related activities such as curriculum design, and three were involved in continuing teacher education. Graciela, however, probably focused more on her teaching, and her research and organizing activities were related to it. Graciela supervised 16 BA and two MA theses and allocated significant time to students’ writing and thesis supervision. She worked mainly within her local ELT community in an ELT BA program.

Table 3 Participants’ Teaching Experiences

| Participant | Years of experience | Curriculum development | ||

| Program revision | Program design | Diploma course design | ||

| Verónica | 10 | 3 programs | Since 2016 | None |

| Graciela | 20 | None | Since 2013 | None |

| Juan | 18 | 5 programs, approximately | Since 2016 | Since 2009 |

| Joaquín | 19 | 5 programs | Since 2016 | 2009-2014 |

Higher institutions worldwide and in Mexico have been implementing policies to promote faculty research. Thus, these four teacher-researchers participated in research activities, and they all published to some extent. Table 4 shows that Joaquín, who was the first to hold a PhD degree, was the participant who published the most. It was probably due to his work at a research center which led him to study diverse issues related to education. He wrote three books as a single author and one with his PhD thesis supervisor, with whom he also wrote four international publications. Joaquín, who built a research and publication career, recognized the role of MA professors and peers in his development and highlighted the crucial role of his PhD thesis supervisor as both his literacy and network broker (Lave & Wenger, 1991).

Table 4 Research Experiences: Publication and Thesis Supervision

| National publications | International publications | Total | Thesis supervision | |||||

| Articles & chapters | Books | Articles & chapters | ||||||

| Author | Coauthor | Author | Coauthor | Author | Coauthor | |||

| Verónica | 2 | 7 | 9 | 6 BA theses | ||||

| Graciela | 2 | 10 | 1 | 13 |

|

|||

| Juan | 3 | 1 | 4 | 11 BA theses | ||||

| Joaquín | 7 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 20 |

|

The other three participants also collaborated with more experienced researchers or scholars who became their literacy or network brokers (Curry & Lillis, 2014; Lillis & Curry, 2010). On occasions, the literacy or network broker had a role only in one or two particular events; in others, they had a crucial role in a period of the participants’ track record. In two cases, the participant and their literacy or network broker became colleagues and participated in the same research group. Graciela and Joaquín, who recognized their professors and thesis supervisors as literacy and network brokers, tended to publish more. Graciela reflected on the role of the thesis supervisor as follows: “I think that the thesis director choice is essential in a postgraduate degree; if you choose well, this could open a lot of doors for you…open spaces, you learn a lot…if it is a good relationship.”

Joaquín, talking about his collaboration in writing an article with his PhD thesis supervisor, acknowledged that:

She’s been a great help. She asks questions…in many cases, I don’t have answers to those questions. And that pinpoints the gaps…in my research project or…the gaps on the interviews, and then I go back into the field and fill those gaps . . . She doesn’t question me [sic] what I’m doing it right or not. She asks questions because she wants to know what’s going on as well . . . I don’t feel she’s judging me…She asks me, and I say, “I don’t know, that’s a good point”…but…go back…to complete, get a holistic understanding…and then she says: “getting closer.”

The preceding has led us to reflect on the crucial role of postgraduate studies and especially thesis supervisors in academic development.

Finally, Verónica, in one of the interviews, talked about a colleague and explained:

The master’s and the work that I’ve been doing with [colleague’s name], that was key; I learned a lot of things...a lot of collaborations and work, and that was key and, actually, that got me into the area of writing. And then, the second thing, when I entered the PhD, my supervisor also expanded my view in literacy.

So, the data in this study seemed to indicate that a close collaboration between a senior scholar and a less experienced one (such as in the cases of Graciela, Joaquín, and Verónica) had a substantial effect on their academic development. It corroborated the significance of professional track records of collaboration and networking activities as socialization opportunities in peripherical legitimate participation (Casanave & Vandrick, 2003; Lave & Wenger, 1991).

Of note is that, in the last ten years, the participants joined two or more disciplinary communities, which implied acquiring two or more memberships (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015). They all started participating in associations such as MEXTESOL, but later, they started taking part in communities more related to their current research interests. Joaquín admitted he had changed his research interests and, consequently, he was not interested in ELT or applied linguistics. He was more into education research but was still struggling to define his research field:

Actually nowadays, right now I am finding some sort of difficulties defining what my area of research or my disciplinary field is if I can say so because, for some reason, I am not really into language teaching anymore. For some time, I was interested in discourse analysis, and I am not doing that anymore. Then, I belong to this group of comparative education, but I am not really working on comparative education. Then, I also do some stuff of social sciences, but I am not really into social sciences in terms of anthropological, or sociological, no [sic] that into that or political analysis. Then, I am also working in some sort of planning and perspective and stuff, but I am not really into this, so right now I would say I have groups. There are groups of people with whom I socialize. I share interests because I would probably open my academic development in different areas. I don’t think I fit into any of those groups because I am not really into the different topics.

The other three participants continued in ELT or applied linguistics yet also had new research interests, leading them to join new disciplinary communities and acquire multiple memberships.

In their paths towards authorship, there were various tensions that scholars confronted and coped with regarding their social contexts and gender (reported in other studies such as Trujeque-Moreno et al., 2015). Among these is the tension between collaborative and individual work. While they all acknowledge the role of collaboration and networking in their track records, two participants, Joaquín and Verónica, admitted the role of lonely periods, especially during the PhD programs, and for Joaquín while researching and writing his three books. For instance, Verónica explained:

The PhD has been, at least in that program, like a lonely process or lonely path because once you get [what] your topic is, you know what you have to do, but eh…but that work allows you to do things with other people, and I’m not very sure if I really collaborate formally with people. But I think that informally I’ve talked to some people in the area.

These two participants, however, confronted these lonely periods differently. Verónica implied these lonely periods were challenging, whereas Joaquín associated them with being productive: “I’ve been living alone for some time now, and it is difficult to go out in [city]. It could be very dangerous. So, I have been studying and writing most of the time.”

Higher education policies in Mexico have also promoted collaboration and networking since 2002 with support and funding to research groups or Cuerpos Académicos (López-Leyva, 2010) and other projects. This policy challenged researchers to develop organizational competencies. Table 5 shows that Juan is the participant who was more involved in organization activities and worked with five organizations.

Table 5 Organization Experiences: Collaboration and Networking

| Organizations | |||

| National | International | Key collaborations and networks | |

| Verónica | Collaborator of a research group and had just started to form her research group | Legitimate code theory |

|

| Graciela | Research group member | None |

|

| Juan |

|

USA Embassy |

|

| Joaquín | Research in Education | Comparative education |

|

At the time of the study, Juan was working with three organizations. In the interviews, he mentioned mainly three network brokers in different moments of his professional path, as stated in the following quote:

In my academic life, as a professor, I should say, Fabiola, [she] is a key person. . . . I have mixed feelings. I should say Saúl was a key person. . . . I have to recognize that Manuel has also been a key person…Recently, people like Raquel; she’s been very supportive and has shaped my perspective in different ways.

Discussion and Conclusions

Agency Strategies in the Participants’ Track Records

Each participant engaged in their professional communities at different moments of their paths (Priestley et al., 2012). The level and kind of engagement depended on the professional they wanted to become (Archer, 2010) and on the collaborations and networks they had constructed in the different dimensions (teaching, organizing, and researching) of their professional life. The short narratives below attempted to present each participant’s involvement in their collaborations and networks and the meaning they gave to their “landscape of practice” (Wenger-Trayner et al., 2015).

Graciela was widely involved in teaching activities, and her research and organization activities were related to them too. Moreover, her published work had a local and national scope. Most of her presentations, courses, and program revision participations took place in her local ELT community. Nevertheless, she worked with close collaborators in national and international professional activities. Her professional identity and development were shaped by her key collaborations with mentors, literacy brokers, and network brokers since she started her MA program in ELT. She capitalized on these ties in her co-authorships (publications) with mentors and colleagues.

Consequently, she was asked to be part of a research group by senior members of her local community of practice. A key area of broad participation was her role as a thesis supervisor for an undergraduate and a graduate program in ELT, allowing her to work with many students. Even here, Graciela focused more on teaching academic writing for research purposes. Her reflections on her social skills showed high awareness of her collaboration style, which is people-oriented. During the second interview, she focused mainly on the powerful influence of the non-professional groups she belongs to and on her learning process to collaborate and network, which also permeated her social strategies and tactics to work with others in her workplace. We identified her as a team player who liked to make close effective relationships with the people she worked with. Now, she wants to expand her collaborations and networks, yet she provided a little reflection on her future professional projects.

Verónica was involved in different professional activities; two of the most salient were researching and teaching at a public university. Her presentations and publications focused on different topics related to academic writing. She also had ample local and national participation in ELT through her presentations and publications. She reported that her PhD in applied linguistics increased her national and international collaborations and networks while looking for answers for her thesis project. She learned to work with peers and senior professors in two research communities: one in ELT and another focused on specialized writing issues.

Furthermore, she started the organization of her research group at her workplace. We could identify that Verónica’s collaboration style was outcome-oriented. Even though she reported that she experienced a lonely path while working on her PhD thesis, she managed to look for answers outside her local research communities, which opened new doors for collaboration with other groups. Her reflections showed that she was unsure about her formal collaborations, but she acknowledged that, at least informally, she collaborated with different professionals in her areas of interest.

Juan’s track record showed that he was widely immersed in organizational activities, and his research and teaching were strongly associated with these activities. His organizational participation and collaboration were evident at local, national, and international levels, as he was a coordinator of an educational department in an ELT program and a national English program for teachers’ professional development. Moreover, he has been an international program coordinator for almost a decade. These experiences in coordination clearly showed his leadership role. Juan participated locally and nationally as an active member of committees in curriculum evaluation, language testing, and committees for BA graduation processes, including thesis supervision.

He was president of Puebla’s chapter in MEXTESOL and organized and co-organized events for ELT professionals locally, nationally, and internationally. His presentations at academic events and publications were closely related to his main interests: professional development, curriculum design and evaluation, and language policies. At the time of the study, Juan was studying a PhD program in applied linguistics at an internationally recognized institution in the United Kingdom that would allow him to develop further as a researcher and teacher and expand on his organization activities as a prominent network broker in his community and others. His professional identity and development were shaped by his in-depth collaboration in different projects with colleagues and mentors since he started his MA program in ELT and by network brokers since he became immersed in organization activities locally (Vangrieken et al., 2015).

Joaquín’s data indicated two clear periods in his path: A first period mainly dedicated to English teaching and teacher education in ELT, and a second one in which he moved to a new state, worked at a research center, got his PhD in social sciences, and migrated into a new disciplinary community, education. Although during his first period, he published in ELT, most of his publications were related to issues about school management and the Mexican educational system. He was mainly interested in issues of inclusion, equity, marginalization, and poverty for the design of public policies and educational planning. Both his PhD program and work in the research center created the conditions for him to study these issues. While he studied for his PhD, he published as a second or first author, mostly with his thesis supervisor, who became both his literacy and network broker. After his PhD graduation in 2017, he published mainly as a single author (three books and eight articles or book chapters nationally and internationally). He continued to belong to a productive research community, participated in events and conferences, and belonged to the editorial board of two journals edited for a couple of such conferences. Joaquín was mainly immersed in teaching in his first period but showed significant research interest. During his second period, he was primarily dedicated to research and taught in BA, MA, and PhD programs. Thus, Joaquín’s professional identity and development were mainly shaped by his research.

As presented previously, these teacher-researchers had similar educational backgrounds; however, they had diverse professional paths. The four interviewees displayed an understanding of their circumstances, their challenges at the time, and whom they wanted to become; in other words, their past, present, and future. These reflections enlightened our understanding of the participants’ degrees of involvement in teaching, organization, and research in their professional communities at the different stages of their track records. Priestley et al. (2012) view agency as an emergent, temporal phenomenon that an individual achieves as a result of their engagement in a specific context. This view of agency can explain these findings. Furthermore, as mentioned above, the interviews displayed reflections in which the participants discussed their professional development. These reflections revealed an ecological perspective of agency within different temporalities: past, present, and future (Archer, 2010; Emirbayer & Mische, 1998). Thus, each participant capitalized on their interests, strengths, and context at that particular moment in their paths.

Literacy and Network Brokers’ Influence on the Participants’ Agency Development

Literacy brokers seem to be fundamental in the participants’ publishing processes and creating the environment for a participant to implement their agency. Those who acknowledge their thesis supervisors as their literacy and network brokers publish the most, for example, Joaquín and Graciela. The theory of peripherical legitimate participation enlightens these relationships between thesis supervisors and supervisees-in other words, direct collaboration between a more experienced member of the community and a novice one (Lave & Wenger, 1991)-and conveys a more profound awareness of the context where participation takes place (Wenger, 1998). One of the participants, Graciela, explained clearly the way she worked “alongside” her thesis supervisor, who helped her gain entrance into thesis supervision: “I invested a long time in these reading; this was a collaborative work that I started alongside [her thesis director], she involved me in thesis reading.”

Verónica had a more senior colleague she recognized as a network broker than a literacy one. Juan reflected more on his four network brokers and how they supported his projects and decisions at different times of his track record. Finally, Joaquín, as mentioned above, acknowledged the role of MA professors and especially the collaboration with his PhD thesis supervisor as key in his professional development.

The participants in this study reported their scholar paths initiated in their MA programs. Thus, creating the necessary conditions to support professionals’ collaboration and networking practices with other scholars locally, nationally, and internationally in postgraduate programs seem to be crucial in future academic development. Then, more strategic policies that promote collaboration and networking are necessary for higher education, which could lead to higher productivity in the professional activities already described.

Limitations and Implications

All the participants permitted to use the data we collected about their professional track records. Moreover, being insiders in this community of practice allowed us to have a more in-depth understanding of the participants’ context. Nevertheless, our closeness to them might add subjectivity to our interpretation of relationships and results in this research. Therefore, a follow-up study could explore the paths of professionals in similar ELT communities in other public Mexican universities or countries.

This study has produced mainly three questions for future research. First of all, as three female researchers, our continuous reflections on gender, which emerged both from our female participants’ data and our own experiences, have given rise to many questions on women’s participation in academic communities, such as the tensions between women’s personal and professional development.

Another issue raised during the study was the possibility of exploring the participants’ publications from a discourse analysis perspective, both those publications written by a single author and those coauthored.

Furthermore, the writing process sparked interest in how each of us participated in investigating and writing this article. It was a two-year process, and we were three coauthors from different generations who participated actively in the discussions of data collection, data analysis, and the writing and rewriting of the article using diverse strategies at different moments of the writing process. Although each participant’s degree of engagement varied at the different stages depending on our previous research experiences and personal issues, we discussed most points of our concern together, first on-site and later virtually during the last COVID lockdown. Thus, we would also be interested in studying the coauthoring process.

As shown above, this study has, hopefully, shed light on networking processes and practices in this specific context and has posited new questions, especially on collaboration and coauthoring processes and practices.