A Qualitative Research Synthesis of EFL Writing Studies in Colombia

English as a foreign language (EFL) writing has received widespread attention in second language writing (Pelaez-Morales, 2017). Writing is currently viewed as a cognitive and cultural activity involving writers, texts, and contexts (Shaw & Weir, 2007; Silva, 2016). We adopted this encompassing view of writing to conduct a qualitative research synthesis (QRS) of EFL writing studies in Colombia published during the last three decades.

QRS is a type of secondary research that provides a standalone systematic literature review of primary research on a specific area (Chong & Reinders, 2021). Unlike meta-analyses, which synthesise quantitative data, QRS synthesise qualitative data from studies (Chong & Plonsky, 2021; Chong & Reinders, 2021). Research syntheses employ systematic methodological protocols for literature search and analysis, comparable with primary research regarding systematicity, transparency, reliability, and replicability (Chong & Reinders, 2021).

QRS is becoming popular in education but is still less common in applied linguistics and TESOL (Chong & Plonsky, 2021). QRS helps examine qualitative findings of classroom-based studies and offers a comprehensive view of the outcomes of pedagogical interventions and the factors associated with instructional effectiveness, teachers’ and learners’ perceptions, beliefs, and experiences in various contexts on a common topic (Chong & Plonsky, 2021). QRS helps identify research trends, propose research agendas, and reach practitioners, enabling them to participate in the research-pedagogy dialogue (Chong & Reinders, 2021).

A QRS in EFL writing in Colombia is relevant as Colombian language policies have promoted English instruction, including writing, since primary school (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2014). However, as a skill, writing is not assessed in the national tests (i.e., Saber 11 and Saber Pro; Guapacha-Chamorro, 2022). This lack of writing assessment limits our view of Colombian EFL learners’ writing proficiency. Despite primary research on EFL writing in Colombia, the lack of research syntheses in this context limits our understanding of the area’s current state and the identification of strengths, weaknesses, and future directions.

Against this backdrop, a QRS of EFL writing studies may inform practitioners, policymakers, and researchers of the most common research trends and areas of development and improvement. A research agenda can be proposed from this synthesis.

Previous L2 Writing Syntheses

Previous L2 writing syntheses examined L2 writing theories, teaching, and research (e.g., Manchón & Matsuda, 2016; Pelaez-Morales, 2017; Riazi et al., 2018) and writing assessment research (Zheng & Yu, 2019). These syntheses provided essential overviews of the most salient research trends, themes, foci, theoretical and methodological orientations, contexts, participants, and findings in L2 writing. They have informed and advanced the L2 writing field, highlighting the need for further studies in (E)FL contexts (e.g., Riazi et al., 2018).

Riazi et al. (2018) argue that “EFL and FL writing differ from ESL [English as a second language] writing in terms of students’ and instructors’ needs, contexts, and purposes” (p. 50). These differences are relevant for the present study because Colombia is a representative EFL context. From that view, the research syntheses by Riazi et al. (2018) and Zheng and Yu (2019) informed the present QRS because they examined L2 writing studies published in journals and highlighted the need to document FL contexts.

Riazi et al. (2018) reviewed 272 empirical studies published in the Journal of Second Language Writing between 1992 and 2016. They analysed the contexts, participants, foci, theoretical orientations, research methodology, and data sources. The authors found that the typical research contexts and participants were undergraduates in U.S. universities (i.e., ESL contexts). Feedback and instruction were the main foci, and cognitive, social, socio-cognitive, genre, contrastive rhetoric, and critical theories were the main theoretical orientations. Qualitative studies were predominant, alongside multiple sources, text samples, and elicitation data sources. From their findings, Riazi et al. characterised the field as centred on “adult L2 writing in English at universities” (p. 51). They suggested the need for a broader focus on “more diverse macro and micro contexts with participants from different levels of education” (p. 51).

Zheng and Yu (2019) reviewed 219 empirical studies published in the Assessing Writing journal (2000-2018) to provide a view of writing assessment development. The authors used content analysis to examine the studies’ contextual, theoretical, and methodological orientations. They found that validity and reliability, feedback, and testing performance were the main research foci, whereas L1 undergraduates in US universities/colleges were the most frequent research contexts and participants. The most common theoretical orientations were generalizability theory, sociocultural theory, and writing as a cognitive process. Quantitative research and text data represented the most frequent primary data source and methodology. The authors called for mixed-methods studies including diverse participants.

Overall, the need to document the field of EFL writing in diverse contexts and the relevance of English writing in educational settings make the present study relevant.

Scope of the Study and Research Question

This historical QRS condenses EFL writing research published between 1990 and 2020 (September) in Colombian journals as these appeared in the early 1990s. This study aims to gain insights into the state of EFL writing in the Colombian context, identify common research trends, and provide suggestions for future development. This QRS contributes to developing the L2 writing field in local and global contexts.

The present QRS draws on previous L2 writing research syntheses. However, it is more comprehensive in examining most components of research reports, such as authorship, publication year, foci, methodology (context, participants, research paradigm, design, data collection methods, and analyses), validity, reliability, ethics, findings, limitations, and further research.

We analysed the studies’ authorship (e.g., university lecturers, schoolteachers) to identify the principal contributors in EFL writing in Colombia and the extent of teachers’ and scholars’ involvement in this research area. The publication year gives insights into Colombia’s EFL writing research development. The focus relates to a study’s main interest, aim, and discipline (e.g., assessment, instruction) and casts light upon the most and least common research trends regarding theories and purposes.

Methodological aspects include context, participants, research paradigm, design, and data collection methods and analyses. The analysis of the research context and participants reveals the most and least researched settings (e.g., schools, universities), participants (e.g., university students, school students), and studies’ scales (e.g., small, large). The analysis of the research paradigm, design, and data collection methods and analyses provides a view of how EFL writing has predominantly been investigated in the Colombian context.

Validity, reliability, and ethics were also discussed because their report ensures the research studies’ robustness and ethical procedures (Phakiti & Paltridge, 2015). Although evaluating the reliability of qualitative studies is a controversial topic in the qualitative research community, it is frequently recommended as good practice, as it ascertains transparency of the analysis process and the trustworthiness of results (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020).

The studies’ findings offer a view of the outcomes of pedagogical interventions, the factors that influence EFL writing instruction, learning, and assessment, and teachers’ and learners’ perceptions, beliefs, and experiences in various contexts on a common topic. Limitations inform the readers about the studies’ critical issues, whereas further research provides suggestions for further development.

This QRS synthesises EFL writing studies in Colombia regarding the following research question: What are the research trends on EFL writing in Colombia in the last 30 years regarding authorship, year, focus, methodology (context, participants, research paradigm, design, and data collection methods and analyses), validity, reliability, ethics, findings, limitations, and further research?

Method

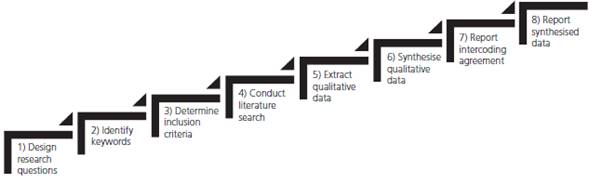

We adapted Chong and Plonsky’s (2021) QRS methodological framework because most Colombian publications were qualitative. We also synthesised the qualitative data of mixed-methods studies. Quantitative studies were absent. This section explains the eight systematic methodological steps implemented, including our proposed intercoding agreement step (Figure 1).

Step 1: Design Research Questions. QRS is guided by one or several research questions. Our research question derived from the lack of QRS in EFL writing in Colombia and research interests.

Step 2: Identify Keywords. We searched for the relevant literature from Colombian journals using the following keywords: EFL writing, L2/second/foreign language writing, academic writing, writing, and English writing. We also searched titles, abstracts, keywords, introductions, and methodology sections.

Step 3: Determine Inclusion Criteria. Chong and Plonsky (2021) locate the inclusion criteria step after the literature search. We inverted the order because predetermined criteria helped us select the publications as we searched. Before the search, we defined research reports (RRs) to differentiate them from other publications (e.g., pedagogical experiences). RRs draw on primary data sources and have theoretical and methodological perspectives (Phakiti & Paltridge, 2015). We adopted five inclusion criteria for the selection of RRs:

primary research (pedagogical experiences and thematic reviews were excluded),

conducted in Colombia with Colombian participants,

conducted in EFL writing contexts (studies in other languages were excluded),

published between 1990 and 2020 (September), and

published in Colombian journals, as they are generally peer-reviewed and meet high standards for publication. We excluded international journals (because they were beyond the scope of our study) and unpublished studies (e.g., theses and conference papers due to their limited access).

Step 4: Conduct a Literature Search. We searched the EFL writing RRs using the keywords and inclusion criteria in Steps 2 and 3. The search was performed on Publindex, the Colombian indexer, to identify the Colombian journals in applied linguistics, linguistics, and education. There are no specialised journals on EFL writing in Colombia. Although some journals were not classified into the four ranking categories (A1, A2, B, C), they were included in our review to keep track of the history of EFL writing in Colombia since 1990.

We searched journals and articles independently to enable comparisons of search results (Chong & Plonsky, 2021). We also checked the references of each article to find more related publications. The search yielded 19 journals (Table 1) and 63 publications.1

Table 1 List of Colombian Journals Used for the Qualitative Research Synthesis

| 1 | Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal |

| 2 | Cuadernos de Lingüística Hispánica |

| 3 | Cultura Educación y Sociedad |

| 4 | Enletawa Journal |

| 5 | Enunciación |

| 6 | Folios |

| 7 | Forma y Función |

| 8 | GIST - Education and Learning Research Journal |

| 9 | HOW Journal |

| 10 | Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura |

| 11 | Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning |

| 12 | Lenguaje |

| 13 | Lingüística y Literatura |

| 14 | Matices en Lenguas Extranjeras |

| 15 | Opening Writing Doors Journal |

| 16 | Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development |

| 17 | Revista Colombiana de Educación |

| 18 | Revista Boletín Redipe |

| 19 | Signo y Pensamiento |

Step 5. Extract Qualitative Data. Qualitative data were extracted using data management software. We first conducted an exploratory data analysis independently in Excel 2016 using a predetermined coding scheme: authorship, publication year, focus, methodology (research paradigm design, length, contexts, participants, data collection methods, and analyses), validity, reliability, ethics, findings, limitations, and further research. We adopted Riazi et al.’s (2018) approach of not interpreting the information from our perspective but extracting and reporting the authors’ literal descriptions to keep their views. We did not analyse the theoretical orientations because they were not always stated clearly or explicitly. The data not provided was coded as unreported. After the exploratory data analysis, we compared and discussed our Excel matrices and refined the initial codes by renaming, adding new categories, and specifying descriptions. Next, the unified list of categories was input into NVivo 12 for a second independent round of analysis. The refined coding scheme is summarised in Table 2.

Table 2 Coding Scheme

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Publication year | Three decades: 1990-2000; 2001-2010; 2011-2020 |

| Author | University lecturers, schoolteachers, undergraduates, stakeholders |

| Research focus |

|

| Methodology | |

| Context |

|

| Participants | EFL learners (primary, secondary, tertiary levels) and EFL instructors |

| Sample size | In quantitative research, 30+ participants might represent large sample sizes (Pallant, 2016). In qualitative research, sizable samples are not required (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) |

| Paradigm | Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) |

| Design | Qualitative research: action research, case studies, ethnographic, narrative, critical analysis, design-based (Hyland, 2016) Quantitative research: true experiments, quasi-experiments (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) Mixed-methods research: explanatory sequential, exploratory sequential, and convergent (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) |

| Study length | 16 weeks (academic semester), 7 to 12 months, and > than one year |

| Methods | Elicitation (self-report through interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires), introspection (writers’ data on writing processes through oral or written reports such as protocols, stimulated recall, diaries, or journals), observation (writers’ writing behaviour data observed directly through audio or video recordings, eye tracking, and keystroke logging), and text data (writing samples; Hyland, 2016). Our study classified tests as text data and researchers’ journals (or field notes) as observation methods |

| Data analysis | Qualitative data analysis: discourse, conversation, content and thematic analyses, and grounded theory (Friedman, 2012) Quantitative data analysis: t-tests, ANOVA, etc. (Pallant, 2016) |

| Validity | Appropriate sampling procedures, instrument piloting, member checking, expert checking, and triangulation (Friedman, 2012) |

| Reliability | Coding data reliably, a reliable coding protocol, coder training, and intra- and inter-rater reliability (Phakiti & Paltridge, 2015) |

| Ethics | Informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, potential risks, and benefits (Phakiti & Paltridge, 2015) |

| Findings | Positive and negative outcomes reported by the authors |

| Limitations | Reported by the studies’ authors: sample size, instruments, among others |

| Further research | Reported or unreported |

Step 6. Synthesise Qualitative Data. We used content analysis for “coding data in a systematic way in order to discover patterns and develop well-grounded interpretations” (Friedman, 2012, p. 191). The categories and subcategories were created deductively (from L2 writing literature) and inductively (from the data).

Step 7. Report Intercoding Agreement. We added Step 7 to the framework to ensure the reliability of the analyses and results. QRS is highly structured and usually involves multiple reviewers to reduce bias and show transparency (Chong & Plonsky, 2021). Intercoding agreement was calculated by comparing the frequencies in each category from the two researchers’ independent analyses. We revised our differences in frequencies and content until reaching more than 90% agreement.

Step 8. Report Synthesised Qualitative Data. The synthesised findings of authorship, publication year, focus, methodology, validity, reliability, ethics, limitations, and further research are reported in frequencies (the most and least frequent categories and subcategories) through tables and figures. The report of the studies’ findings is presented using a narrative approach, identifying similarities and differences in results and factors.

Findings and Discussion

The following section presents the findings and discussion of all the categories synthesised to identify common research trends, strengths and weaknesses, and other orientations.

RR’s Publication Year and Authors

Table 3 summarises the results of publication years and authors.

Table 3 Years and Authors (N = 63)

| n(%) | |

| Years | |

| 1990-1999 | 1(1.6) |

| 2000-2010 | 19(30.2) |

| 2011-2020 | 43(68.2) |

| Authors | |

| University lecturers | 39(61.9) |

| Schoolteachers | 14(22.2) |

| University lecturers and schoolteachers | 5(7.9) |

| Undergraduate students | 2(3.2) |

| Schoolteacher - University lecturer | 1(1.6) |

| University lecturers and stakeholders | 1(1.6) |

| Unreported | 1(1.6) |

As shown in Table 3, RRs increased noticeably in the last two decades. This surge might be related to the increasing importance of EFL writing in Colombia and worldwide in educational settings, the rise in journals, and the fact that university lecturers need publications to get promoted. As to authors, university lecturers are the main contributors to Colombian EFL writing research, authoring alone (39, 61.9 %) and co-authoring with schoolteachers (5, 7.9%) and stakeholders (1, 1.6%). Schoolteachers are in a distant second place (14, 22.2%). It could be that university lecturers have better research conditions (time and resources) and incentives to publish compared to schoolteachers.

Although infrequent, publications by schoolteachers, undergraduates, and stakeholders (e.g., coordinators, administrators, principals) are meaningful because they might reflect their attempts to close the research-practice nexus, a critical area in teacher professional development. It is crucial to encourage classroom language teachers to conduct and publish their research (Hyland, 2016) due to its positive implications for the authors and their communities.

Research Reports’ Foci

Identifying the RRs’ foci was challenging because they lacked explicitness and clarity. Table 4 summarises RRs’ foci.

Table 4 Research Reports’ Foci (N = 63)

| n(%) | |

| Research area focus | |

| Writing instruction | 61(96.8) |

| Writing assessment | 2(3.2) |

| Writing view focus | |

| Context-centred studies | 49(77.8) |

|

|

28(44.4) |

|

|

12(19) |

|

|

8(12.7) |

|

|

4(6.3) |

|

|

2(3.2) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

|

|

9(14.3) |

|

|

7(11.1) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

|

|

8(12.7) |

|

|

6(9.5) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

|

|

4(6.3) |

|

|

2(3.2) |

|

|

2(3.2) |

| Writer-centred studies | 8(12.7) |

|

|

6(9.5) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

| Text-centred studies | 6(9.5) |

|

|

4(6.3) |

|

|

2(3.2) |

The RR’s foci were classified into two major categories: research area and writing view. Within the research area category, writing instruction (61, 96.8%) was the main focus, compared to writing assessment (2, 3.2%), indicating a need for writing assessment research in Colombia. Although L2 writing instruction and writing assessment are independent areas, they inform each other. Moreover, “effective writing instruction requires appropriate assessment” (Weigle, 2016, p. 473).

As to the writing view, we identified that context-centred studies were more frequent (49, 77.8%) than writer- (8, 12.7%) and text-centred studies (6, 9.5%). Context-centred studies relate to social, political, and cultural factors influencing academic discourses and writers’ learning, identity, and attitudes toward writing (Hyland, 2010). Pedagogical interventions were included as contextual factors influencing writing. Writer-centred studies examine writers’ cognitive writing processes (planning, drafting, revision; Ong, 2014) and individual variables such as age, perceptions, experiences, motivation, beliefs, agency, and identity (Kormos, 2012). Text-centred studies examine the written products through text analysis (e.g., linguistic or discursive aspects) or scores (Matsuda, 2015).

As shown in Table 4, context-centred studies focused mainly on instruction and feedback, similarly to Riazi et al.’s (2018) and Pelaez-Morales’s (2017) findings. Peer feedback, collaborative writing, cooperative work, peer tutoring, genre-based approach, and process-based approach were the most explored approaches to improving students’ writing, compared to innovative theories such as task-based approach and critical literacy. The second focus of context-centred studies was technological tools (e.g., graphic organisers, virtual platforms, blogs, and Duolingo). Studies on non-technological tools (e.g., portfolios and instructional materials such as worksheets) were infrequent due probably to the increasing influence of digital tools in English writing.

Writer-centred studies’ main focus was on EFL writers’ experiences and identities, followed by beliefs and practices and internal and external factors influencing writing. Text-centred studies focused on analysing linguistic and discourse features.

Context-centred studies focused mainly on instruction and feedback reflects teachers’ interest in improving students’ writing and show a predominantly teacher-centred view of writing. It is necessary to investigate EFL writing from writers’ and texts’ perspectives to provide an encompassing view of writing (Silva, 2016).

Research Reports’ Methodology

Context, Participants, and Sample Size

Context includes macro and micro contexts. Regarding macro contexts or geographical areas, most studies were conducted in Bogotá, the capital city (25, 39.7%), whereas the rest were spread across different geographical regions (34, 54%), as shown in Figure 2. Four studies (6.3%) did not report the geographical context. Regarding micro contexts or specific research settings, universities (54%) were more predominant than schools2 (38.1%) and language institutes (7.9%).

The large number of studies conducted in Bogotá and universities might be due to the high number of universities in the capital city, university lecturers’ appropriate conditions and incentives for doing research, and the relevance of academic writing for university students. These results suggest a need to broaden the geographical and educational contexts where EFL writing is researched in Colombia to identify other contexts’ and writers’ characteristics and needs.

Regarding participants and sample sizes, learners were the most common participants, with preservice language teachers being the most investigated (Table 5). Less research involved in-service teachers; secondary and primary school learners; children, adolescents, and adults in language institutes; and students with special needs. Most studies (40, 63.5%) employed large sample sizes, usually intact classes, whereas small samples (16, 25.4%) were less frequent. Several studies (7, 11.1%) did not report the sample size. In some studies, the sample size report was inaccurate because the whole class was reported as the study’s sample size and later the researchers specified that the data belonged to a smaller sample of participants.

Table 5 Participants and Sample Sizes (N = 63)

| n(%) | |

| Learners | 59(93.7) |

|

|

32(50.8) |

|

|

18(28.8) |

|

|

10(15.9) |

|

|

4(6.3) |

|

|

17(27) |

|

|

6(9.5) |

|

|

2(3.2) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

| Instructors | 3(4.8) |

|

|

3(4.8) |

| Instructors and learners | 1(1.6) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

| Sample size (# of participants) | |

| Small | 16(25.4) |

|

|

16(25.4) |

| Large | 40(63.5) |

|

|

36(57.1) |

|

|

2(3.2) |

|

|

2(3.2) |

| Unreported | 7(11.1) |

University learners were the most common participants, probably because most researchers were university lecturers. Also, university students produce more academic writing than school learners. Preservice language teachers were typically investigated because they are trained to teach and assess languages, making them an important research focus. Our results confirm Pelaez-Morales’s (2017) and Riazi et al.’s (2018) findings, identifying universities and undergraduates as the most commonly investigated contexts and participants in L2 writing research. Consequently, we agree with Riazi et al.’s (2018) characterisation of the field as centred on “adult L2 writing in English at universities” (p. 51). Researching various participants might provide insights into their characteristics, processes, and needs. Most studies employed intact classes that give a view of small classroom contexts. There is a need for further studies in other educational settings and with larger sample sizes (e.g., schools) to broaden the scope of EFL writing.

Research Paradigm, Design, and Length

According to Table 6, qualitative studies (57, 90.5%) were predominant, clearly contrasting with mixed methods (1, 1.6%) and quantitative research (0%). Five studies did not report the research methodology. Within the qualitative paradigm, action research and case studies were the most common research designs, confirming Pelaez-Morales’s (2017) and Riazi et al.’s (2018) findings that qualitative methods are typically used to investigate L2 writing instruction.

Table 6 Research Paradigm and Design (N = 63)

| Research paradigm | Research design | n(%) |

| Qualitative | 57(90.5) | |

| Action research | 29(46) | |

| Case study | 17(27) | |

| Ethnography | 2(3.2) | |

| Design-based | 1(1.6) | |

| Biographical/narrative | 1(1.6) | |

| Experience systematisation | 1(1.6) | |

| Unspecified | 6(9.5) | |

| Mixed-methods | 1(1.6) | |

| Sequential exploratory and sequential explanatory | 1(1.6) | |

| Quantitative | 0(0) | |

| Unreported | 5(7.9) | |

Hyland (2016) argues that the choice of methodology “will largely depend on what we believe writing is, the model of language we subscribe to, and how we understand learning” (p. 117). Hence, we could claim that the predominance of qualitative research might reflect researchers’ sociocultural view of writing, looking into individuals and social interactions (Hyland, 2010). This is probably why most studies focused on developing students’ writing through contextual factors (e.g., blogs, instruction) and interactions (e.g., feedback, collaborative writing).

The predominance of action research and case studies is perhaps more convenient for language teachers in their classrooms. Action research helps solve language learning- and teaching-related problems, whereas case studies help better understand a person, group, or context (Hyland, 2016). The fact that most studies took place in classrooms supports Hyland’s (2016) claims that writing research tends to favour data gathered in naturalistic conditions.

The absence of quantitative studies related to observation and measurement (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) could be influenced by language teachers’ lack of literacy in quantitative methods and assessment (Giraldo, 2019). Such reasons might also explain why writing assessment research is uncommon in the Colombian context, as it traditionally involves quantitative approaches and statistical knowledge (Weigle, 2016).

Most studies were relatively short regarding study length, lasting an academic semester (16 weeks; 30, 47.6%), followed by a small number of longitudinal studies (13, 20.6%). Short-term studies were common probably because they fit into the researchers’ teaching periods (university semesters) and are more practical in terms of time than longitudinal studies. A relatively high number of studies (20, 31.7%) did not report the study length. This omission may threaten the studies’ validity, as this information helps understand the findings’ scope and impact and allows for further replications and comparability.

Data Collection Methods and Analyses

Most studies employed multiple data collection methods and sources (Table 7). Text data (52, 82.5%), elicitation (48, 76.2%), and observation (40, 63.5%) were more frequently used, compared to introspection (10, 15.9%). These results align with Riazi et al. (2018), who found that L2 writing researchers used multiple data sources, mainly text data and elicitation.

Table 7 Data Collection Methods (N = 63)

| n(%) | |

| Text data | 52(82.5) |

|

|

45(71.4) |

|

|

7(11.1) |

| Elicitation | 48(76.2) |

|

|

33(52.4) |

|

|

26(41.3) |

| Observation | 40(63.5) |

|

|

32(50.8) |

|

|

12(19.1) |

|

|

2(3.2) |

| Introspection | 10(15.9) |

|

|

9(14.3) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

Note. Some studies employed different techniques concurrently within the same data collection method. For instance, a study could have used interviews and questionnaires, classified into elicitation methods. This simultaneity explains why, in some cases, the addition of the figures of the subcategories seems to be higher than the total for the general category.

Regarding the data analysis approach (Table 8), only 37 studies (58.7%) reported this information; the remaining studies (26, 41.3%) did not. We wonder why the authors and reviewers of such articles were unaware of this omission, which threatens a study’s validity and reliability. The results show that grounded theory (28, 44.4%) was the most common qualitative data analysis approach, whereas text analysis (12, 19.1%), thematic analysis (2, 3.2%), and content analysis (1, 1.6%) were the least used. Qualitative data analyses were predominant probably because they are often rich or deep, revealing detailed and complex information about the human experience of language learning (Friedman, 2012). In contrast, quantitative data analysis approaches were infrequent.

Table 8 Data Analysis Report and Approaches (N = 63)

| n(%) | |

| Data analysis approach not reported | 26(41.3) |

| Data analysis approach reported | 37(58.7) |

| Grounded theory | 28(44.4) |

| Text analysis | 12(19.1) |

|

|

7(11.7) |

|

|

4(6.4) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

| Thematic analysis | 2(3.2) |

| Content analysis | 1(1.6) |

The low frequency of text analyses (e.g., scores, linguistic and discourse analyses) and the minor focus on text-centred studies appear to misalign with the high occurrence of reports of text data collected. In contrast, the high frequency of researchers’ journals and field notes aligns with the high percentage of action research. Likewise, the low frequency of introspection aligns with the low number of writer-centred studies.

Students’ writing improvement was generally analysed from students’ and teachers’ perceptions through elicitation (e.g., questionnaires) and observation (e.g., researchers’ field notes and journals). Evidence of students’ writing improvement also requires text analyses and scores to support the claims and the validity and reliability of the results. The lack of introspection methods confirms the need to study writers’ cognition and personal experiences.

Research Reports’ Validity, Reliability, and Ethics

Previous L2 writing reviews have not examined studies’ validity, reliability, and ethics. We did not evaluate the validity and reliability of the authors’ research but reported the aspects they mentioned. According to Phakiti and Paltridge (2015), validity (in quantitative research) or trustworthiness (in qualitative research) refers to the substantive and methodological soundness of a study, encompassing theoretical and methodological coherence. Reliability is about the quality of instruments, results, and consistency in data coding and constructs measurement. Ethical procedures include informed consent, anonymity, confidentiality, ethics approval, and informing participants of the investigation’s potential risks and benefits.

Many studies did not report validity, reliability, and ethics (Table 9). Validity was more frequently reported than reliability and ethics. Within validity, sampling procedures and triangulation of data sources or methods were commonly described, whereas instrument piloting, member checking, and expert checking were the least reported. Instrument validation and piloting were often mentioned without explaining the procedures. Furthermore, participants’ language level description was not always informed and supported with language test evidence.

Table 9 Validity, Reliability, and Ethics (N = 63)

| n(%) | |

| Validity | 32(50.8) |

|

|

18(28.6) |

|

|

17(27) |

|

|

3(4.8) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

|

|

1(1.6) |

| Reliability | 5(7.9) |

|

|

5(7.9) |

| Ethics | 14(22.2) |

|

|

11(17.5) |

|

|

7(11.1) |

Note. The simultaneous report of several ethics, validity, and reliability aspects explains why, in some cases, the addition of figures of the subcategories seems to be higher than the total number for the general category.

Concerning reliability, only five studies (7.9%) reported having a second coder, or rater, analyse the data. Only one study reported intercoding agreement. Ethics was infrequently reported (14, 22.2%); only consent forms and anonymity were mentioned. The lack of rigour in reporting validity, reliability, and ethics might be due to word limit constraints or that these aspects were not emphasised previously, particularly in qualitative studies.

Research Reports’ Findings

We synthesised the RRs’ findings to identify common patterns, trends, and issues. A word of caution is necessary here because not all the studies reported all the information rigorously needed to understand the findings.

Context-Centred Studies’ Findings

Context-centred studies investigated the effect of a theory, strategy, material, or tool in writing instruction.

Theories. The process-based writing approach, genre-based approach, feedback, cooperative work, collaborative work, project work, and task-based approach were reported as positive in improving students’ writing learning, performance, motivation, attitudes, and perceptions. The process-based approach (PBA) reportedly increased the motivation, attitudes towards, perceptions, and awareness of the writing process of adult writers (Zúñiga & Macias, 2006), adolescents (Ariza, 2005), and young learners (Arteaga, 2017; Melgarejo, 2009; Sánchez & López, 2019). PBA helped students improve content (Sánchez & López, 2019), idea and paragraph organisation (Arteaga, 2017; Rivera, 2011; Sánchez & López, 2019; Zúñiga & Macias, 2006), vocabulary and grammar (Artunduaga, 2013; Melgarejo, 2009; Sánchez & López, 2019).

The genre-based approach raised young writers’ genre and audience awareness when planning and revising their texts (Arteaga, 2017). Short stories and creative writing improved students’ text coherence, cohesion (Hurtado, 2010), grammar (Pinto, 2017), authorial voice (Hernández, 2017; Hurtado, 2010), and identity (López, 2009). University students improved argumentative writing (Chala & Chapetón, 2013), whereas preservice teachers improved their understanding of context, purpose, and audience (Correa & Echeverri, 2017). Additionally, genre-based activities promoted university students’ confidence and positive attitudes toward writing (Chala & Chapetón, 2013; Pinto, 2017).

Cooperative/collaborative work (CW), project work (PW), and feedback (e.g., peer tutoring, peer editing, peer support) improved students’ writing development and motivation. Through PW and CW, primary school students improved their critical thinking, writing process (Ruiz, 2013), text organisation, grammar, and punctuation (Yate et al., 2013). Peer editing, peer feedback, and CW allowed high achievers to provide linguistic scaffolding to low achievers (Aldana, 2005; Díaz, 2010; Salinas, 2020) and helped them improve audience awareness (Aldana, 2005), writing process awareness, and vocabulary (Caicedo, 2016). CW and PW helped university students develop academic writing skills when producing a research paper (Carvajal & Roberto, 2014) and provided scaffolding (Vergara & Perdomo, 2017). Writers’ texts improved aspects such as idea organisation, cohesion, coherence (Carvajal & Roberto, 2014; Díaz, 2014), length, fluency (Díaz, 2014), language use (Robayo & Hernández, 2013; Vergara & Perdomo, 2017), critical thinking (Robayo & Hernández, 2013), and metalinguistic awareness (Vergara & Perdomo, 2017).

CW, PW, and peer feedback provided peer scaffolding (Guerra, 2016), fostered teamwork (Carvajal & Roberto, 2014; Yate et al., 2013), attitudes (Aldana, 2005), autonomy (Vergara & Perdomo, 2017), motivation, confidence, and values (Carvajal & Roberto, 2014; Celis, 2012; Díaz, 2014; Ruiz, 2013). Students also increased their positive perception of writing (Díaz, 2014), error awareness (Celis, 2012), and performance (Salinas, 2020).

The task-based approach also improved students’ vocabulary and grammar (Ciprian et al., 2015).

Strategies. The design of a writing course for preservice teachers and a writing assessment system were used as strategies to identify weaknesses in writing teaching, learning, and assessment and ways to improve them. Academic writing courses enhance preservice teachers’ writing discourse (task and audience), syntax, vocabulary, and conventions (grammar, capitalisation, parts of speech, punctuation) in paragraphs and essay writing (Marulanda & Martinez, 2017). Likewise, a writing assessment system helped refine constructs, writing tasks, and scoring criteria to meet course standards. This system also helped students improve syntactic complexity (Muñoz et al., 2006; Muñoz & Álvarez, 2008).

Materials. Language-learning technological tools, such as Duolingo, helped Down Syndrome students improve in producing words and phrases (Salcedo & Fernández, 2018). Blogs and interactive digital stories fostered secondary school students’ attitudes and motivation toward writing, awareness of language mistakes, and text length (Guzman & Moreno, 2019; Rojas, 2011). Virtual courses, including games, online readings, videos, forums, and computers, boosted students’ writing processes, linguistic and discourse aspects, and academic text production (Berdugo et al., 2010; López, 2017; Ochoa & Medina, 2014). Virtual courses promoted collaborative writing, self-assessment, and peer assessment and increased students’ attitudes, interactions, and learning engagement (Berdugo et al., 2010; Lopez, 2017; Ochoa & Medina, 2014). Essential factors for successful learning include parental and social support, early stimulation of educational technologies (Salcedo & Fernández, 2018), more hours for the English language class (Rojas, 2011), and more technological tools (Berdugo et al., 2010).

Non-technological tools, such as graphic organisers, improved secondary school students’ argumentative (Mora et al., 2018) and descriptive texts (Reyes, 2011). Portfolios developed first-semester university students’ vocabulary and grammar (Sierra, 2012). Instructional materials, such as worksheets, positively influenced first-graders cognitive skills and teacher and peer mediation (Muñoz, 2010).

Integration of Theories, Strategies, and Tools. Feedback using screencasts (Alvira, 2016), Moodle (Espitia & Cruz, 2013), blogs (Gómez & McDougald, 2013; Quintero, 2008), Storybird (Herrera, 2013), and collaborative hypertext writing with concept maps (López, 2006) advanced students’ writing process, motivation, interaction, and error awareness. The genre-process approach with e-portfolios enabled students to be decision-makers and critical thinkers and enhanced discursive and linguistic aspects (Cuesta & Rincón, 2010).

In general, context-centred studies claimed that PBA, genre-based approach, collaborative/cooperative learning, feedback, project work, and task-based approach were positive for improving EFL students’ writing (processes and texts), attitudes, interactions, and motivation.

Writer-Centred Studies’ Findings

Writer-centred studies examined writers’ perceptions, beliefs, practices, experiences, identities, and factors influencing writing. Regarding EFL writers’ perceptions and beliefs about writing, second graders’ attitudes and perceptions about writing changed from personal to social conventions through CW and L1 use (Ruiz, 2003). In-service EFL teachers viewed academic writing as a way of reporting information. Their writing lacked rhetorical awareness (Anderson & Cuesta, 2019) and was hindered by their low language proficiency and lack of synthesising skills, writing practice, time, and peers’ critical feedback (Cárdenas, 2003). In-service EFL teachers’ personal and professional motivation helped teachers overcome the challenging demands of journal publishing (Cárdenas, 2014).

Regarding EFL writers’ experiences and factors influencing writing, family and school were reported as the primary environments through which preservice EFL teachers accessed written culture (Colmenares, 2010). Writing can be deeply affected by “turning points” and change from a happy personal experience to a stressful, standardising school activity (Colmenares, 2010; Viáfara, 2008). Teachers’ instruction and students’ lack of L2 knowledge, insecurity, language transfer, and time constraints hindered students’ writing, causing frustration and unwillingness to use the target language (Alvarado, 2014). However, writers find learning opportunities during challenging experiences (Colmenares, 2010), generally characterised by grammar-and-translation teaching practices (Viáfara, 2008). Preservice EFL teachers’ identity was influenced by collaborative work (Caviedes et al., 2016).

Thus, writer-centred studies found that writers’ perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, practices, and identities are influenced by positive and negative instructional experiences and individual variables.

Text-Centred Studies’ Findings

Text-centred studies investigated linguistic and discursive features. Linguistic analyses found that L1 (Spanish) interferes with L2 written production, as seen in frequent syntactic and lexical errors by first-year university students (Londoño, 2008; López, 2011) and in L1 written structures and word-by-word translation identified in L2 texts (López, 2011). Discursive analyses found that university students’ texts often lacked cohesion and coherence, authorship, audience awareness, and authorial voice (Arboleda, 1998; Colmenares, 2013).

Explicit instruction on grammar (López, 2011) and cohesive devices (Arboleda, 1998) was recommended to improve EFL learners’ text quality. Students also need to be exposed to diverse genres (apart from essays), topics (e.g., personal experiences, autobiographical stories, and life stories), and digital magazines (Colmenares, 2020). Using EFL text corpora and computational corpus linguistics allows language teachers and researchers to do semantic, lexicographical, pragmatic, sociolinguistic, linguistic, register, and discourse analyses and identify EFL learners’ interlanguage levels and their most frequent errors (Pardo, 2020).

Research Reports’ Limitations and Further Research

Few studies reported their limitations (18, 28.6%) and areas for further research (21, 33.3%). The limitations reported included low participant engagement and attitudes, small sample sizes, time constraints for intervention and data collection, resource constraints, and shortcomings in data methods and analyses.

Conclusions and Research Agenda

This QRS examined 63 EFL writing RRs published in Colombian journals between 1990 and 2020 (September). It aimed to inform the state of this area in Colombia by identifying trends and areas of strengths and weaknesses and to propose a research agenda. To this end, we answered the following research question: What are the research trends on EFL writing in Colombia in the last 30 years regarding authorship, publication year, focus, methodology (context, participants, research paradigm, design, data collection methods, and analyses), validity, reliability, ethics, findings, limitations, and further research?

Based on our synthesis, the primary research trend is that EFL writing in Colombia has predominantly been researched from a qualitative perspective and focused on writing instruction and feedback at the university level, centred on pedagogical interventions and views of adult EFL writing. Less emphasis has been placed on the study of writers (e.g., cognitive processes, introspection) and texts (e.g., performance and text analysis), with the former contributing individual factors that affect writers and the latter reporting on actual outcomes. Based on the above findings, we conclude that EFL writing is a developing field in Colombia, and we, therefore, propose the following research agenda.

Research by Other Contributors

University lecturers are the main contributors to EFL writing research. Further research by schoolteachers and education stakeholders might provide insights into the initial stages of EFL writing in the Colombian educational context and the conditions and policies necessary to improve EFL writing teaching, learning, and assessment. It entails more support for preservice and in-service teachers’ research and academic writing skills through professional development programmes and co-authorship with expert researchers.

Research Broadening Foci

Most Colombian EFL writing studies explored feedback, process-based, and genre-based approaches. Less is known about the complex dynamic systems theory (Cameron & Larsen-Freeman, 2007) and the sociocognitive (Atkinson, 2011) and identity (Matsuda, 2015) approaches. Such approaches provide an encompassing view of writing, allowing researchers to investigate writers, texts, and contexts.

Writing instruction has been the primary research focus, reporting the effectiveness of pedagogical interventions from teachers’ and students’ perceptions. Less research has been done on writing assessment. Writing assessment studies inform instruction, language policies, test designers, and test validation. It examines variables affecting students’ writing cognitive processes, performance, motivation, and teachers’ and raters’ performances. Statistical analysis of students’ performance and linguistic measurements (e.g., complexity, accuracy, fluency) of text data might provide strong evidence of students’ writing improvement, supplementing teachers’ and students’ perceptions.

Research Broadening Methodological Approaches

Qualitative studies, mostly action-research designs, were predominant. Longitudinal studies and analyses such as critical analysis, auto-ethnography, and text analysis would cast light on writing development and provide a view of writers and texts. Large-scale studies are needed to support robust generalisations on factors affecting EFL writing. Quantitative and mixed-methods research is also required to provide an encompassing view of writing from quantitative (e.g., performance) and qualitative (e.g., perceptions) perspectives. The lack of these studies might be related to their complex design and time requirements. It implies that academic programmes include a quantitative component to help pre- and in-service language teachers develop literacies in this research area.

Research Broadening Contexts and Participants

University students in main cities were mainly researched. Further studies might investigate the writing of students with special needs, children, adolescents, and instructors and explore other geographical areas and settings, such as small cities, rural areas, schools (public, private, rural, and urban), language institutes, and worksites. A broader spectrum of participants and settings would portray the features and needs of writers in other contexts and conditions.

Research Reporting Validity, Reliability, Ethics, Limitations, and Further Research

Our synthesis identified that most studies missed reporting validity, reliability, ethics, limitations, and further research. We encourage researchers to report on those aspects to enhance the robustness of their reports. We propose a set of guidelines for authors and reviewers to strengthen and evaluate the quality of RRs (Table 10) so they align with national and international publication standards.

Table 10 Guidelines for Research Report Evaluation

| Sections and information to be reported, justified and described clearly/sufficiently/accurately | Reported | |||

| Yes | No | Partially | Comments | |

| Introduction | ||||

|

|

||||

| Literature | ||||

|

|

||||

| Methodology | ||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

| Information allowing for replication | ||||

| Findings and discussion | ||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

| Conclusions | ||||

|

|

||||

| Validity, reliability, and ethics | ||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

| Limitations | ||||

| Further research | ||||

Limitations of the Present QRS

The present QRS narrowed its scope to EFL writing and journal-based data. Further research syntheses might examine studies in languages other than English and search for sources, such as theses and international journals. Additional reviews might consider analysing the studies’ theoretical orientations to provide a comprehensive analysis of RRs, as in our case, this aspect was difficult to analyse.