Introduction

Task-based language teaching (TBLT) emerged as an alternative pedagogy to challenge the inadequacy of communicative language teaching in India in the 1980s. Since then, it has become a widely researched language-teaching approach, generating reluctance (Swan, 2005) and advocacy (Ellis et al., 2019; Long, 2016).

The influential role of TBLT in language research and policy has placed it as the dominant method for foreign and second language teaching (Hu & McKay, 2012; Van den Branden, 2016). However, the practitioners’ perspectives, learning, and experiences on TBLT remain limited in research, thus limiting TBLT’s potential for impacting classrooms meaningfully (Bygate, 2020; East, 2017).

Indeed, East (2014, 2017, 2021) has advocated for research that explores how preservice and novice teachers integrate this method into their work, including their attitudes, challenges to learning the task concept, and TBLT’s implementation.

We agree with Bygate’s (2020) urgent summon to explore TBLT research, not just as an end in itself but as a resource in the light of “the practices, demands, pressures, and perspectives of stakeholders in real-world language classrooms” (p. 275). This is particularly relevant to the many challenges school administrators, parents, teachers, and students faced during the COVID-19 lockdown (Madianou, 2020). Research has looked into teachers’ responses to the challenges of remote instruction (Corrales & Rey-Paba, 2021) and their effective use of digital technologies (Fořtová et al., 2021); however, few studies have examined how preservice teachers coped with these particular teaching circumstances. Our study addresses these concerns and aims to contribute to the calls for exploring TBLT as a tool within the myriad practices and knowledge practitioners hold, especially amidst current vulnerable times.

Thus, this article describes how preservice teachers adjusted their emerging teaching practices, informed mainly by TBLT, while transitioning to remote instruction amidst the COVID-19 pandemic-enforced lockdown. The research question guiding this study asked: How did 13 preservice teachers in an English language teaching (ELT) program adapt their implementation of TBLT-supported lessons in their field practicum during the transition to remote teaching amidst the COVID-19 lockdown?

Our findings describe the TBLT principles these preservice teachers used to design and teach their English as a foreign language (EFL) lessons in person and remotely. Shedding light on how preservice teachers grappled with TBLT principles amidst the world health crisis, we hope to contribute to understanding preservice teachers’ learning, emerging practices related to TBLT, and tasks within remotely instructed EFL lessons. Such understandings will add to current research on teachers’ learning in L2 teacher education research (García-Montes et al., 2022; Sagre et al., 2022) and illuminate new perspectives on teachers’ learning of TBLT.

Literature Review

TBLT and Tasks

Characterizing tasks within TBLT can be a complex endeavor (Van den Branden et al., 2009), but the scholarly consensus is that tasks should have four defining characteristics (Ellis, 2009). First, tasks primarily focus on meaning during message negotiation with a communicative purpose; therefore, a task requires learners to manipulate both the semantic and pragmatic functions of language to convey their message during a communicative exchange. Second, a task requires the completion of a communicative outcome rather than a linguistic one. Third, tasks require interaction, engaging learners’ linguistic resources rather than a pre-planned language structure. Fourth, a task includes a gap to be filled; for example, learners may need to exchange their opinions to reach a consensus or find missing information needed to achieve the task goal (Ellis, 2009).

Such characterization is fundamental for conceptualizing tasks as the organizing unit of the learning activity (Ellis, 2009; Van den Branden et al., 2009). However, research with TBLT practitioners (Erlam, 2016; Li & Zou, 2022) has demonstrated that understanding and following these criteria poses difficulties for language teachers. In line with this, Erlam (2016) examined how teachers in a New Zealand school implemented the four criteria outlined by Ellis (2009). By examining 43 teachers’ work plans, Erlam found that teachers struggled to include learners’ linguistic resources (67 %) and a communicative gap in their tasks (79%). Thus, the execution of TBLT principles may look different in practice than the theoretical framework suggests.

Teachers’ Implementation of TBLT

Given the global prevalence of TBLT in different teaching contexts, studies have explored TBLT and its pedagogical applications in real classrooms. On the one hand, some studies have pointed out the challenges teachers face to understand, take ownership of, and “successfully” implement TBLT. Some challenging factors include teachers’ misunderstanding of TBLT, thus resulting in a “narrow” interpretation of TBLT and difficulties adapting it to the context (Ellis et al., 2019). Another challenge is teachers’ uncertainty about the characteristics of tasks; for instance, East (2014) and Van den Branden (2016) doubt teachers’ effective implementation of TBLT, as they have found that teachers struggle to differentiate tasks from traditional exercises.

Teachers may also endure tensions between the learner-centered pedagogy of TBLT and traditional teacher-centered approaches. For instance, the learner-centered focus of TBLT requires more expertise and is more demanding than other communicative approaches (Plews & Zhao, 2010). TBLT requires understanding learners’ real-life tasks and authentic communicative needs; furthermore, TBLT favors purposeful and comprehensive language use rather than accuracy, making learning more meaningful and relevant. Lai (2015) also pointed out that this learner-centered pedagogy is at odds with culturally embedded traditional approaches in Asia, as teachers’ and students’ roles change. Addressing such challenges requires efforts to include teachers’ and learners’ cultural practices, like teacher-learner interactions, within TBLT implementation.

The reported challenges to implementing TBLT in real classrooms have provoked criticism about this approach’s theoretically and academically prescribed conceptualizations that prevent teachers from enacting it (Swan, 2005). To address such criticism, scholars have examined the teacher’s role in TBLT implementation in real classrooms (East, 2014; Ellis, 2017). East’s study (2021) with beginning language teachers in New Zealand provides valuable insights into teachers’ understanding of TBLT. The practitioners’ conflicting views of TBLT actively evolve through a training program, impacting their initial teaching practice. Similar studies have evidenced the complexity of TBLT implementation in classrooms (East, 2021). This finding underscores the need for long-term research that explores TBLT implementation as a gradual, repeated, reflective, and revisional process for teachers. In sum, these studies summon practitioner and research collaboration (Long, 2016), advocating for a broader and more collaborative vision (Bygate, 2020) to bridge theory and practice by including teachers’ perspectives and contributions to the pedagogical development of TBLT.

Preservice Teachers and TBLT

Bridging the gap between theory and practice in TBLT will benefit from exploring the learning experiences derived from initial training and early applications of this method. Therefore, the challenges of implementing TBLT should be more closely explored among preservice teachers, whose teaching repertoire is still being shaped.

In their initial stages of teaching practice, preservice teachers hold onto their expectations and beliefs on how to teach in the context they encounter in the classroom (Glisan & Donato, 2017). For instance, when examining preservice teachers’ emerging beliefs, Johnson (1994) found that they hold precarious images of themselves as teachers and teaching, which conflicts with their instructional practice. Johnson claims that preservice teachers likely default to practices inconsistent with their self-images as teachers because of the constraints of their first teaching experiences, confronting their preconceived notions of teaching to their actual instructional practice. Consequently, Johnson highlights the importance of a practicum environment that supports teachers in discovering and shaping their beliefs.

This situation is mirrored in preservice teachers’ first attempts at implementing TBLT: their complex perceptions of teaching shape how they incorporate prior and novel concepts to acquire procedural teaching knowledge. In this regard, Littlewood (2016) states that preservice teachers struggle to overcome their apprenticeship of observation (Lortie, 1975) when implementing TBLT principles. Littlewood argues that TBLT is fertile ground for preservice teachers’ emerging practices combining experiential and learned knowledge.

The divergence in how TBLT training develops into teaching practice for beginner teachers has increased interest in the subject. For instance, Ogilvie and Dunn (2010) argue that despite TBLT being included in teacher education courses and well received by preservice teachers, this disposition does not translate into classroom practice. The authors point out the need to offer more support and attention to preservice teacher education to instill the connection between theory and practice in preservice teachers, enabling them to apply what they learn about TBLT in their classrooms.

Similarly, Chan (2012) adds to the understanding of how beginner teachers incorporate TBLT into their lessons by adjusting their practices to specific contexts. By examining the patterns of interaction and strategies included in 20 lessons from five novice teachers in Hong Kong, Chan found that teachers’ lesson structure differed in terms of strategies, provision of scaffolding, and attention to learners’ needs. These differences were even more apparent during the implementation of the lesson. The study accentuates the complexity of teachers’ balancing their knowledge and intentions in TBLT with challenges in their teaching.

All this research highlights the need to address the variable ways in which preservice teachers use their training in TBLT to respond to the characteristics of their teaching contexts.

Challenges During the Pandemic

Emerging research on the emergency transition to remote instruction due to the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed that teachers around the globe made drastic adjustments to their teaching. Teachers’ adjustments and reworking of their lessons and practices and their reflections and learnings during the lockdown have motivated a renewed look at how teachers encompass theory to face the uniqueness of their teaching realities. For instance, Corrales and Rey-Paba (2021) studied instructors’ perceptions in a group of teachers at a private university. These teachers reported development in areas other than teaching, mainly in skills to adapt to a new teaching modality and methodologies, as well as in peer support and a more humane approach to teaching and learning.

García-Botero et al. (2021) explored how over 400 students in an ELT BA program used computer-assisted methodology for teaching/learning during the COVID-19 lockdown. The study revealed students’ perceptions of their teacher’s methodologies, underscoring the lack of empathy and the overuse of lectures during online lessons. These elements are then related to students’ active and autonomous learning and class interaction, highlighting the ongoing need for teacher training on remote teaching and for reflecting on teacher roles to ensure empathy, communication, and assessment throughout the lessons.

Fořtová et al. (2021) followed a qualitative analysis to examine the teaching experience of 63 teachers in a master’s program in the Czech Republic. Analysis of their post-lesson reflections revealed that the participants found the online environment limiting and described it as an unauthentic learning experience. However, despite their initial reluctance to the new environment, the teachers shifted to being able to adapt their practices to the new environment and maneuver the technologies required to deliver their lessons.

The previous studies briefly showcase emerging research on how the appropriation of learned teaching practices occurred during a challenging time, such as the transition to remote instruction. However, to our knowledge, adjusting to a new modality in TBLT has not been investigated. Hence, this study focuses on how novice teachers adapted their emerging TBLT practices to face the transition to remote teaching during the COVID-19 lockdown. Our previous review shows that this topic has not been explored yet. Such exploration will add to understanding how practitioners take ownership of their acquired knowledge in the face of unique constraints in their teaching contexts.

Method

This qualitative study (Lapan et al., 2012) was conducted in an ELT program at a public university in the Colombian Caribbean region during the first semester of 2020. The study followed a documentary analysis of the preservice teachers’ lesson plans, teaching materials, and reflection reports during their practicum course, led by one researcher. In this program, preservice teachers take the practicum course after two semesters of teaching methods courses that focus on the theoretical backgrounds of language teaching. During the practicum, the preservice teachers are usually expected to teach 40 hours of EFL in high school with the supervision of an experienced high-school teacher who acts as a formative supervisor. The preservice teachers’ tasks generally include planning and delivering lessons, designing materials, and assessing students.

The participants in this study faced disruption in their field experience due to the emergency transition to remote instruction. When the lockdown started, all the participants had planned and delivered an average of two lessons in their practicum, which required between three and five weekly hours of direct teaching. Thus, the first half of the practicum classes were delivered in person, and the second half took place remotely with the aid of teaching guides, which students were required to work on independently. On average, the participants implemented three lessons through teaching guides delivered to students once a week using WhatsApp, Zoom, and Google Docs.

Participants

The participants in this study (Andrea, Pamela, Ernesto, Naty, Lorena, Jose, Miguel, Juliana, Jaime, Kelly, Sara, Sergio, and Milena; all pseudonyms) were 13 students (eight women, five men) in their ninth semester of an ELT undergraduate program and who were taking the teaching practicum course. With one exception, participants designed and implemented the lessons individually. Because they instructed the same level groups in an English teaching program offered by their home university to public primary schools, three students (Pamela, Naty, and Lorena) worked as a group during in-person teaching. However, due to changes in the participants’ distribution during remote teaching, two worked as a team, while the third (Lorena) worked individually in the same school. The lesson plans of this small group were analyzed, paying attention to the participants’ work dynamics.

The participants served as preservice teachers in secondary grades in public schools in urban and rural towns in Córdoba, a department located in northern Colombia. Secondary school learners’ ages varied across grades in the schools, ranging from 11 to 20 years old. Learners belonged to low- and middle-class communities whose linguistic repertoires include standardized Spanish and local dialects. Preservice teachers described their learners as active, dynamic, and curious. However, the participants also mentioned the learners’ lack of access to digital technologies as one of the main limitations of teaching during the pandemic.

Data Collection

We collected data concerning the tasks from the unit and lesson planning artifacts (e.g., plans and materials) preservice teachers created during their practicum experience. At least one in-person and two remote lesson plans were analyzed per participant. In total, we analyzed 47 lesson plans collected through Google Drive folders. We also collected the participants’ perceptions regarding their lesson planning and their reactions to the day-to-day teaching process through self-reflection reports that they completed during and at the end of the semester as part of their final project for the course. These self-reflections were presented in videos, blog posts, and written journals.

Data Analysis

Data analysis followed a deductive approach, using the definition of TBLT principles in Ellis (2009) as a predefined analysis framework. We conducted a documentary analysis of the participants’ lesson plans, artifacts, and self-reflection reports. We organized the data according to type and teaching modality. The categories used for the analysis were generated according to the operationalization of TBLT principles in lesson planning. Similarly, the participants’ comments in their self-reflection reports were analyzed for their reference to the themes indicated in the analysis framework. Through this analysis, we obtained a detailed description of the elements in the lesson plans and self-reflection reports and found correspondences with TBLT principles. We discussed and reached a consensus over discrepancies following intercoder reliability practices that foster systematicity and transparency of the data coding process and reflexivity among team members in qualitative research (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020).

Results

The analysis of the lesson plans demonstrated that the preservice teachers’ planning decisions generally involved various task types and TBLT principles. Furthermore, we observed differences in the participants’ in-person and remote designs. Below, we describe the most salient findings for each principle.

Focus on Meaning

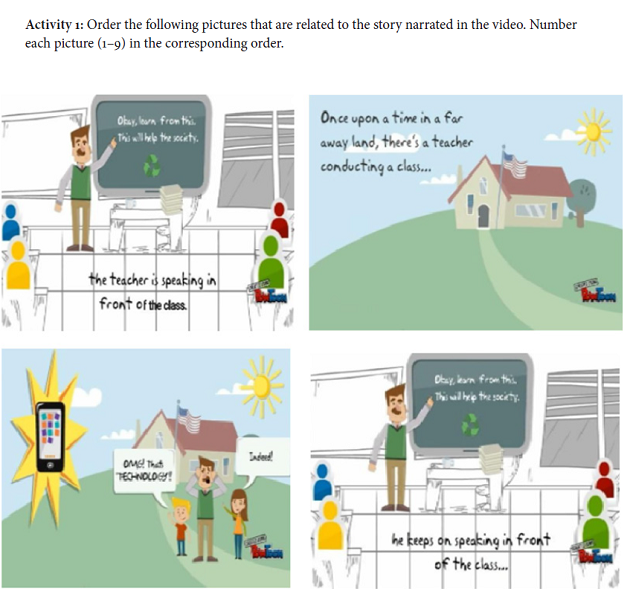

Our analysis of the lesson plans revealed that focus on meaning was the most used principle during in-person and remote lessons. The participants resorted to multimodal texts to facilitate a focus on meaning in their tasks. Milena used a poster (Figure 1) about dreams and a video about youth aspirations to focus on describing plans for the future in her remote lessons. She provided guiding questions and prompted students to demonstrate their understanding of the main themes in these texts.

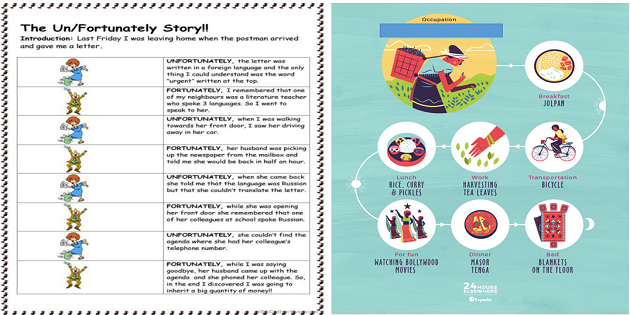

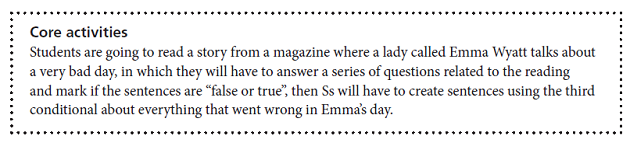

Andrea also focused on meaning by having students extract information from pictures and videos about famous landmarks worldwide. Miguel also used pictures (Figure 1) to trigger students’ descriptions of tourist places in Colombia. Similarly, Sara relied heavily on infographics that illustrated people’s routines, and Jaime included a text that combined pictures and printed text to exemplify the moves of a story (Figure 2). These preservice teachers’ tasks included multimodal descriptions of places, dreams, routines, or anecdotes, completed synchronously or asynchronously, depending on each participant’s teaching context.

Our analysis also revealed that focusing on meaning became difficult for some participants during remote instruction. We observed a repeated instructional pattern that required initial meaning-making from images and then moved to a focus on form. We describe two participants’ lesson plans to evidence such a pattern.

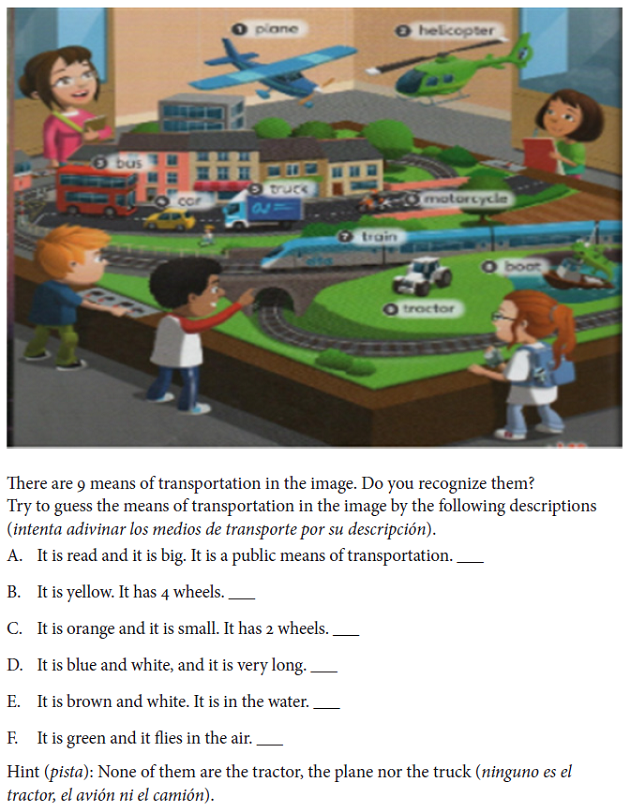

Lorena’s planning (Figure 3) started requiring students to make meaning from a picture portraying a town model and various means of transport, accompanied by textual clues describing the latter. However, a focus on the vocabulary of means of transport and the grammar forms became more evident in the final stages of the lesson plan. A similar pattern was observed in Ernesto’s planning for his first virtual lesson, which included an online memory game and images of people’s leisure activities. Ernesto’s shift toward vocabulary is more evident as he included lists of related words and phrases that students were expected to use for filling in the blanks.

These applications of the focus on meaning contrast with the participants’ reflections, demonstrating awareness of this principle and its importance for language learning. In her report, Lorena mentioned: “I understand how important it is to give students contexts that they can relate to the knowledge they already have,” thus acknowledging the need to add contexts to her lessons. She also emphasized focusing on context rather than just vocabulary or grammatical forms. She continued: “It is really important not to give them isolated words or vocabulary or only grammar because that wouldn’t work as efficiently as we can do them work.”

These tasks’ descriptions revealed that most participants were aware of the focus-on-meaning principle and tried to include it in their lessons through multimodal texts. However, as they acknowledged in their reflections, remote teaching was challenging. For example, Juliana, Jose, and Ernesto mentioned in their reflection reports that dealing with variables such as student resources, the requirements made by the school tutors, and the remoteness of teaching may have influenced their task design which drew heavily on focus on form. We will review these contextual factors’ impact in the discussion section.

Communicative Outcome

One of the guiding principles of task design is completing a communicative outcome, which may help assess students’ performance (Ellis, 2009). In this study, the principle was often used in both teaching modalities: Seven participants used it during in-person teaching, and nine included it in their task design for remote teaching. Most participants’ outcomes draw on Willis and Willis’ taxonomy of tasks (2001), which the preservice teachers had studied during their methods courses. Common communicative outcomes included producing a list, ranking items, completing a chart, producing a survey, composing a Facebook post, or designing a brochure. We describe how four participants used different task outcomes during in-person and remote teaching and the challenges involved.

In one of the lesson plans for in-person teaching, Jose indicated the students’ ranking of their habits from the least to the healthiest as the outcome his students should achieve by the end of the lesson. He introduced the lesson topic with a pre-task in which students classified flashcards describing teachers’ habits as healthy and unhealthy. Then, he asked student pairs to classify a list of habits into healthy and unhealthy and rank their habits from the least to the healthiest.

In remote teaching, Jose’s task outcomes included creating a list of healthy habits students had in common with the individuals described in three multimodal texts. Each text described a person from one of three groups (Sardinians, Adventists, and Okinawans). Jose designed several task steps to allow students to comprehend the texts and grasp each character’s habits. By doing so, he demonstrated how the outcome guided his lesson planning. Additionally, these steps facilitated focusing on meaning, as students demonstrated an understanding of the texts to list the habits (outcome) they deemed interesting and would like to try in their lives.

Milena also included outcomes consistently within her planning. For one of the in-person lessons, Milena planned a task outcome requiring students to illustrate a person with specific characteristics (e.g., hardworking, passionate) and associate them with a family member who may resemble them. In a subsequent lesson plan, students were asked to rank the habits of effective people they had watched in a video. Milena included several steps to scaffold students’ comprehension of the video; for instance, as a whole class, the students and the teacher brainstormed, listed, and agreed on the five most important habits. This outcome allowed students to demonstrate comprehension of a previously given input in these lessons.

In both lesson plans for remote teaching, Milena included problem-solving and listing tasks that facilitated a communicative outcome. For the first one, Milena included a video that featured teenagers, like her eighth-graders, talking about their dreams. After watching the video, students ordered the traits that would allow these teenagers to achieve their future dreams or goals. Finally, the task outcome included deciding the most crucial factor in achieving future goals.

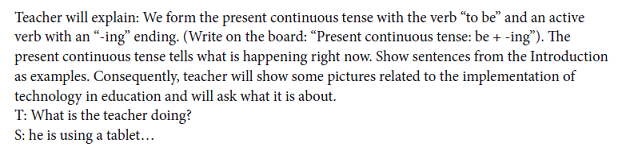

Jose’s and Milena’s communicative outcomes revealed an interest in meaning-making, especially in getting messages across from the multimodal texts in their lesson plans. Conversely, for other participants, including an outcome in their remote teaching tasks was not as straightforward, thus revealing challenges and contradictions. In the case of Ernesto and Juliana, their explicit focus on form obscured their inclusion of the outcome principle. The following lesson plans evidence the participants’ interest in developing a focus on form during their lessons. For instance, Ernesto’s second in-person lesson objectives included recognizing and using the present continuous (Figure 4).

In his planning, Ernesto focused on using technology in school and presented flashcards and multimodal texts that described teachers’ using technological devices in the classroom. He used these texts mainly to explain the uses of the present continuous form, as observed in the type of questions he prepared to ask the class (Figure 4). Only after focusing on the target forms did Ernesto’s lesson include a task with a communicative outcome. He presented students with a video and asked them to sequence pictures (Figure 5).

At first sight, this task’s outcome entailed focusing on meaning by relying on the comprehension of the story sequences. However, the focus on meaning was blurred by the overt inclusion of text exemplifying the present continuous structure (e.g., the teacher is speaking in front of the class). Ernesto’s lesson tasks revealed his struggle to balance focus on meaning and form in his task outcomes, which guided his lesson design during remote teaching. Similar difficulties were observed in other participants’ lessons during remote instruction.

In Juliana’s case, the shift to remote instruction and the lack of opportunities to meet her class synchronically online seemed to have inhibited the inclusion of communicative outcomes. Juliana’s resolution to the abrupt shift in instruction seems to have developed into a more explicit focus on form. The following examples describe Juliana’s use of outcomes before and after the school’s lockdown in March 2020. During in-person teaching, Juliana included task outcomes in her planning, which included matching and telling personal narratives. Through these outcomes, Juliana could balance a focus on form (e.g., second conditional structure) and meaning (e.g., understanding the complications in a narrative; see Figure 6).

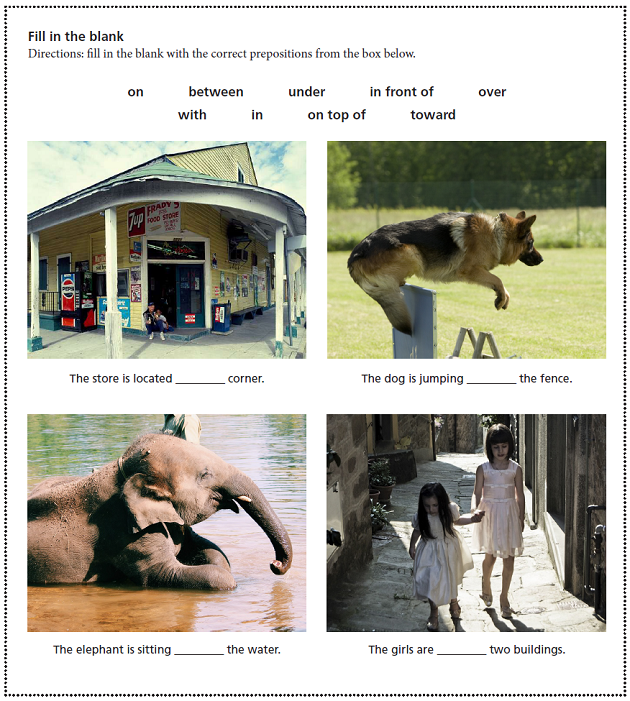

Conversely, Juliana’s focus on form dominated her planning during remote teaching. Juliana did not focus on achieving a communicative outcome for most of her remote lessons. Instead, she relied heavily on solving grammar-focused activities. For example, Juliana’s task in Figure 7 resembled a grammatical exercise to practice prepositions of place. Interestingly, she tried to include a focus on meaning by adding pictures that illustrated prepositions of place, thus trying to move beyond a grammatical exercise.

This strikingly different use of task outcomes in Juliana’s planning seems to have been influenced by the changes in the delivery of instruction and her decision-maker roles in lesson planning. In her reflection, Juliana expressed that “the crisis that arises in the world affected the successful development of this practicum,” implying that the shift to remote instruction prevented her from continuing her practicum as she had initially done. Juliana also reported she had to “plan units and lessons for our formative supervisor to continue teaching students through workshops as well as platforms, taking into account set learning outcomes, instructional goals, availability of time and resources, and teaching methodology.” According to Juliana’s reflection, planning for remote instruction implied moving away from an autonomous teaching role to following her formative supervisors’ requests regarding topics, outcomes, and instruction.

These four participants’ examples demonstrate different levels of awareness and challenges in using the outcome principle; for Milena and Jose, including a communicative outcome seemed to be directly connected to meaning-making. They achieved this by developing task outcomes such as listing, matching, and decision-making tied to comprehending multimodal texts. For Juliana and Ernesto, including a communicative outcome, was more difficult as they tried to balance meaning-making and a focus on form. For Ernesto, including a communicative outcome was a constant struggle in in-person and remote teaching. In Juliana’s case, this struggle seemed to have arisen from the constraints of remote instruction.

Use of Students’ Linguistic Resources

Engaging learners’ linguistic resources in task completion without focusing too much on the pre-planned language structures is a TBLT principle that has been typically challenging for practitioners (Erlam, 2016). Our analysis revealed that most preservice teachers’ attempts to use students’ linguistic resources in their lessons varied when transitioning from in-person to remote teaching. Five participants designed lessons engaging students’ linguistic resources during remote teaching, and only two used this principle during both teaching modalities. Juliana and Lorena included lesson plans which drew on students’ linguistic resources as part of their tasks during in-person and remote teaching.

In one of her in-person lessons, Juliana included an activity for students to create a narrative based on a bad day they had had in the past. Similarly, she introduced a task in a remotely taught lesson by asking students about their favorite trip. She provided a video with instructions to create a postcard with information about the trip. In these lessons, Juliana motivated students to draw on previous experiences to elicit students’ linguistic resources.

During in-person teaching, Lorena (working with Pamela and Naty) designed two tasks, one in which students described their toys and another in which they described their classrooms. Lorena also designed two lessons for learners to draw from their experiences to describe their context in remote teaching. The tasks encouraged learners to extend their use of the language past the lesson’s focus and include linguistic resources that either came from the input (e.g., a video) or their creative handling of the language.

These two participants’ reflections suggest that preservice teachers applied this principle to include learners’ experiences and context in their lessons. In designing these tasks, the participants seemed to focus on students’ limited resources, which were reported in the reflections as challenges during in-person and remote teaching. For instance, Juliana noted that she designed lessons with students’ available time and resources while following the instructional goals. Similarly, Lorena stated that providing a context through which students can use their previous experiences was central to her lesson design; thus, she aimed to provide learners with opportunities to tap into their knowledge of the world when learning a language. This concern for promoting connections between new concepts, previous knowledge, and individual experiences might have influenced the participants’ decision to rely on learners’ linguistic resources in their lessons.

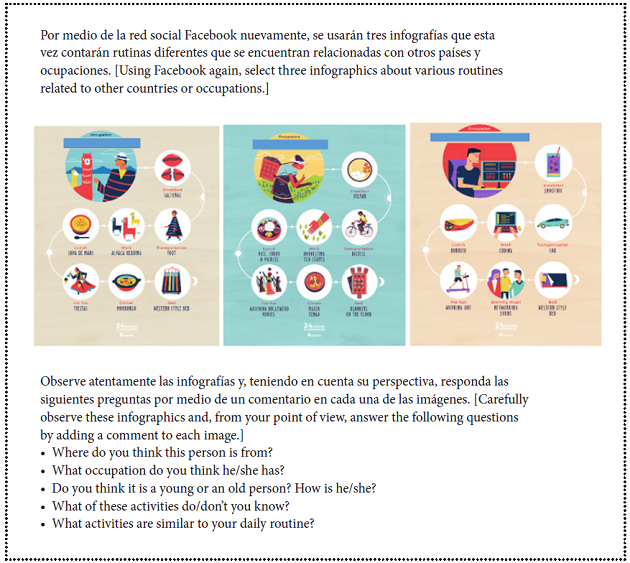

Miguel, Jose, and Sara also included the principle in remote teaching but did not do so during in-person teaching. Miguel designed a remote lesson that showed travel descriptions for students to analyze and create their own. Jose’s task instructions required students’ mother tongue and previously studied information questions to connect to students’ personal information. Sara designed a remote lesson delivered through a Facebook group, which involved learners’ resources to make sense of the input (see Figure 8). Learners were presented with infographics from which to infer information. Sara provided comprehension questions to guide learners through the content and to compare the infographics to their context.

These tasks required learners to use available language forms to comprehend and respond to the input according to their needs. Such planning decision was mentioned in the participants’ reflections. Miguel said, “I had to stop assuming that they know things because they don’t, and, for the activities, I always had a problem with guidance. I realized that I needed to do better instructions for them.” In saying this, Miguel acknowledged that he needed to modify his instructions to better account for the various students’ needs and previous knowledge. Similarly, Jose mentioned he had to create meaningful instructional material adjusted to the limited school resources and his supervisory teacher’s requirements. Sara emphasized that teaching methods needed to allow students to “find new knowledge and ways of learning.” The different ways of drawing on this principle during in-person and remote teaching seemed to be related to the constraint inherent to each modality and the preservice teachers’ ability to address learners’ needs while monitoring their input comprehension.

Information Gap

The document analysis indicated that this principle was the least used by the preservice teachers in both teaching modalities. Five participants utilized this principle to design in-person lessons, adjusting the complexity of the interaction to the task purpose. For example, Kelly asked students to recreate gestures in front of the class for their classmates to guess the meaning of the gesture, which created an information gap during the interaction that one party had to fill.

Other participants created more elaborate tasks that required multiple steps to fill the gap. For example, Andrea created an information-gap task where students would guess a person’s name based on their features. In Ana’s task, the gap was implemented through a “guess who” game in which pairs of students took turns asking questions and guessing different characters shown by the teacher. Pamela, Lorena, and Naty also created two in-person lesson plans, which required learners to fill a communication gap to complete the task. In one lesson, students were asked to draw on the board or in their notebooks as they listened to a classroom description. In the second lesson, students were grouped and given a written description of the toys in a child’s bedroom from a different country and a chart with missing information they needed to complete by asking about other groups’ written descriptions. Similarly, Jose designed a task in which students asked each other questions to figure out classmates’ eating habits, decided whether these habits were healthy, and then created tailored lifestyle suggestions for their partners. The outcome of these lessons hinged on students’ bridging a gap to obtain, evaluate, and make conclusions based on missing information, thus moving from bridging a gap to negotiating information in a more realistic context.

Conversely, none of the participants included information-gap activities in their lesson plans during remote instruction. In the reports, the participants did not demonstrate awareness of the principle, which suggests it is not yet incorporated into their teaching repertoire. However, because some lesson plans included negotiation of missing information, we argue that the preservice teachers had started including a gap to promote communication. Perhaps, the limited interaction opportunities during remote instruction prevented the participants from relying on learners to obtain missing information from either the teacher or other peers. Thus, learners’ interaction, which promotes information discovery, was limited.

Discussion

This study explored preservice teachers’ adaptations of TBLT principles during in-person teaching and transitioning to remote teaching. The analysis of the lesson plans revealed that the preservice teachers implemented the principles differently during the two teaching modalities. Interestingly, the use of the principles varied and sometimes contrasted with what the participants reported in their reflections. Such contrast between novice teachers’ intentions and their implementation of tasks resembles the findings reported by Chan (2012) and Erlam (2016).

The most commonly implemented principle was focus on meaning, followed by including a communicative outcome while tapping into learners’ linguistic resources and including an information gap were the least evidenced principles. Preservice teachers’ lesson plans showed varying approaches for implementing each principle. First, the participants used text modalities such as images, charts, and videos to focus on meaning. Additionally, those who included a communicative outcome in their lessons resorted to specific task types such as item lists, rankings, and classifications.

The analysis suggests that the participants relied on learners’ linguistic resources by providing a rich context to develop their tasks. The communication gap was also included in some in-person lessons, with slight variations in the complexity of the interaction required to fill the gap. Findings highlighted a marked preference for input-based tasks (mainly written/visual texts), teacher-generated tasks, and the return to grammar-focused exercises.

These findings align with previous TBLT research with novice teachers (East, 2017, 2021; Van den Branden, 2016) by underscoring continuous reflections when using task principles. These preservice teachers had been acquainted with TBLT and task principles for around two years. During their methods courses, they designed tasks and lessons, including task principles, implemented them in microteaching, and supervised co-teaching opportunities in primary schools. Despite this robust training support, there seems to be a great distance between their supervised teaching and their field practice, where several decisions had to be made while facing additional challenges, such as the transition to remote teaching.

The observed focus on forms evidenced in some of the preservice teachers’ lessons might have been related to their perceived role change with the transition to remote teaching. In their reflections, the participants expressed more autonomy in lesson plan design during remote teaching. However, the demands from classroom teachers and the schools required them to comply with teaching the forms suggested in the class syllabus. As reported in their reflections, they also looked up to the teachers for advice in the transition. Even though they had more flexibility in their planning, they had to follow topics and language focus previously decided by their supervisor.

Contradictions between teachers’ awareness of these principles and their application in their classrooms, as noted in Lorena’s and Juliana’s lesson plans, confirm that teachers’ understanding of TBLT needs to be negotiated with their contexts and school requirements (East, 2017). Implementing TBLT requires teachers’ will, awareness, understanding, and agreement with the schools’ curriculum and expectations. As Juliana mentioned, her practicum was constrained by her supervisor’s request to include a focus on form, as stated in the syllabus. During in-person teaching, Juliana tried to balance such focus. Still, as remote instruction became the dominant approach, she found more limitations to achieving such balance, reflected in task outcomes more aligned with grammatical exercises.

Similarly, we described the preservice teachers’ challenges to balance focusing on meaning and grammar through our findings. At first sight, these challenges may support previous claims about the teachers’ inability to distinguish between tasks focused on meaning and exercises focused on form (Ellis, 2009; Ellis et al., 2019; Erlam, 2016). Conversely, our analysis of preservice teachers’ lesson plans and reflections showed that most participants understood the difference between tasks and exercises, as did Milena’s, Jose’s, and Juliana’s tasks, which emphasized meaning.

Other participants could adapt the focus-on-meaning principle to motivate their learners at the beginning of their lesson plans and balance their school requests to focus on grammatical forms, as we described in the case of Ernesto, Lorena, and Juliana. Furthermore, most participants included a communicative outcome in their plans, and their reflections showed awareness of this principle, an essential distinguishing trait between tasks and exercises. Although our findings described the participants’ contradictions regarding the focus on meaning and focus on form, these may not indicate a lack of understanding of what constitutes a task, as previously claimed in TBLT research (Ellis et al., 2019; Van den Branden, 2016).

Additionally, our findings underscore the need to understand principles better, such as using learners’ linguistic resources and including an information gap as a practice in learners’ local circumstances. This may require teacher educators to afford opportunities for preservice teachers to discuss and explore ways to adapt methods like TBLT to their specific contexts. One possible way to expand this principle is by understanding language as a local practice (Pennycook, 2010). Exploring, identifying, and valuing learners’ language practices in their communities and local contexts may provide teachers with vital knowledge to build tasks relatable to the learners’ language experiences. Our findings suggest reconciling the methodological (e.g., task principles and characteristics) and contextual elements (syllabi, learners’ needs, language practices, and in-service teachers’ expectations) in lesson planning. Fostering awareness of such a relationship may reflect on the preservice teachers adapting their knowledge of teaching methodologies and pedagogies to provide meaningful and pertinent language instruction. Thus, we underscore the need to integrate field practice and continuous reflection on learning and adapting TBLT.

Conclusion

The present study examined how preservice teachers adapt the principles of TBLT to their emerging teaching practices during the transition to remote teaching amidst the COVID-19 lockdown. The conflicting challenges between teachers’ understanding of TBLT principles and their application in their lessons reveal the need for more practice-based teaching experiences. We showed through our findings that by implementing TBLT in their teaching, the participants in this study could gauge their knowledge of TBLT with classroom practices while dealing with institutional and contextual challenges.

This study described the manifold ways the preservice teachers adapted TBLT to the demands of their teaching contexts. Because of the popularity of methods such as TBLT in EFL research and practice, critiques that warn about top-down methods ignoring local pedagogical practices and leading to ineffective teaching practices deserve attention. Thus, we call for teacher-education research and practice emphasizing reflection and responsiveness to contextual factors so preservice teachers can take ownership of and apply teaching methods and principles meaningfully.

We invite teacher educators and EFL researchers to wonder what is needed to enact TBLT or other teaching methods in EFL contexts effectively. Similarly, the discussion needs to address the suitability of TBLT principles, like the information-gap principle, which may be at odds with teachers’ and learners’ local language practices. A chief concern in TBLT and teacher-education research includes exploring how these principles can be better integrated into lesson planning and task design. Addressing such concerns is pivotal to adapting TBLT to teachers’ and students’ language practices in their local contexts and modes of teaching.

Although the preservice teachers referred to their previous language learning experiences in shaping their beliefs about what good teaching means, such exploration was out of the scope of the aims of the present study. We acknowledge that this is a study limitation and an area that deserves further exploration. Thus, we invite further research to explore preservice teachers’ previous learning experiences, their beliefs about teaching, and how these influence their uptake of EFL methods like TBLT and their enactment in the classrooms.