Introduction

While not ubiquitous, some language policies are increasingly being introduced globally to address educational concerns surrounding equality and equity (Cardona-Escobar et al., 2021; Murray, 2020). While both state and national governments create macro-level policy frameworks, these are operationalized by local actors who turn these macro-policies into practices that align with their context’s needs (Vanbuel & Van den Branden, 2021). Research suggests that teachers interpret, contextualize, or enact language policies (Ball et al., 2012) based on their experiences, ideologies, and agency (Hornberger & Johnson, 2011; Zuniga et al., 2018). Many national language policies in countries where English is primarily taught as a foreign language aim to reform English learning by providing increased opportunities to learn English in primary school classrooms (Cardona-Escobar et al., 2021; Nguyen, 2011; Qi, 2016). It is argued that creating opportunities for learning English or developing language capital equips young people for the 21st century (Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN], 2016; Murray, 2020).

In Colombia, most of the objectives and goals of English language policies have been defined concerning English language proficiency for both students and teachers. These policies have been primarily designed to graduate high school students with a B1 proficiency level in English (according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, CEFRL) and high school teachers achieving a B2 proficiency level alongside the appropriate knowledge to teach the language. However, these goals have remained elusive. This has served as a justification for designing new language policies (Bastidas, 2017; Cadavid Múnera et al., 2004; McNulty Ferri & Usma Wilches, 2005; Usma, 2009a).

Another common thread of Colombian language policies is the homogenization of school curricula, teachers’ methodologies, and assessment practices, which not only challenges schools’ and teachers’ autonomy but also produces technologies of accountability. As some of the language policies have been driven by different political agendas rather than by a needs analysis of the English-as-a-foreign-language (EFL) community (Gómez Sará, 2017; Usma, 2009a, 2009b), some reforms of the last decade overlap. Additionally, most decisions have been made with a top-down approach, in which the MEN and international institutions have focused on ideal planning, ignoring the contextualized reality of EFL public instruction.

In Colombia and elsewhere (Barnes, 2021; Cardona-Escobar et al., 2021; Qi, 2016), EFL policies have focused on increasing English learning opportunities for young people. One of the National Bilingual Program (PNB, in Spanish) policy texts, Colombia’s current English language policy, outlines that one of its goals is to improve:

the coverage and quality of the educational system . . . so that Colombia gets closer to high international standards and achieves equality of opportunities for all citizens. . . . The Suggested Curriculum of English for Kindergarten and Primary School is a concrete element that aims to achieve equality of opportunities. (MEN, 2016, p. 35, emphasis in original, translated from Spanish)

Thus, this paper explores the enactment of the PNB in three public schools, particularly examining how the program aspires for all children to have the same opportunities. To achieve this, we must understand how schools and teachers enact policy, mainly how the English language is employed, understood, and promoted within language classrooms.

Foreign Language Exposure and Use in the Classroom

Scholars have argued that language proficiency is influenced by exposure to the language (De Wilde et al., 2020; Fhlannchadha & Hickey, 2019) and students’ active use of the language within the classroom (Thomas & Roberts, 2011); students are given increased opportunities to learn the target language if they have increased exposure and opportunities to use it inside the classroom. In a Spanish-English bilingual program in a U.S. school, Ballinger and Lyster (2011) found that while students tended to speak with peers in English, their teacher’s language choice shaped their decision to use English or Spanish. Teachers’ and students’ use of their L1 and L2 in the classroom was influenced by teachers’ beliefs about language and language learning (Barnes, 2021; Mellom et al., 2018; Zuniga et al., 2018) and their perceptions of their proficiency in the target language (Van Canh & Renandya, 2017).

Teachers’ beliefs and experiences with language learning can impact their views on how L1 and L2 should be considered and used within classrooms. Many scholars argue that teaching and learning can be influenced by the belief that communication is most effective when only one dominant language is employed (Budach, 2013; Vanbuel & Van den Branden, 2021). Such ideologies are often shaped by teachers’ monolingual biases (Barnes, 2021; Mellom et al., 2018). While it is widely agreed that L1 should never be excluded from language classrooms, the percentage of language use between L1 and L2 can vary and depends on teachers’ perceptions of students’ L2 proficiency levels (Budach, 2013). Teachers tend to primarily use students’ L1 for instructional and classroom activities if they feel the students have limited L2 proficiency. Further empirical evidence suggests that teachers’ L2 proficiency influences their active use of L2, with teachers with less confidence in using L2, utilizing it less for instruction (Van Canh & Renandya, 2017).

Current English Language Policy Landscape in Colombia

The PNB initiative was issued in 2014, and its aims were defined in terms of English language proficiency achievement, which is based on levels (A1-A2 = basic user, B1-B2 = independent user, and C1-C2 = proficient user) established by the CEFRL scale (Council of Europe, 2001). The policy states that students should achieve an A1 proficiency level by the end of primary education. Within the policy, the government committed itself to ensuring that Colombia would be the most educated country in Latin America by 2025. Based on this goal, a study was conducted in 2014 by the Ministry of Education and a U.S. firm to highlight the challenges of English language instruction and learning in Colombia (MEN, 2014). Some of the difficulties that the MEN found included the English language proficiency of teachers and students. According to the report, 54% of high school graduates had the English proficiency level of someone who has never been exposed to the language. A new program was released in 2015 to strengthen the policy of the PNB: the Programa Nacional de Inglés (National Program of English; MEN, 2014).

The PNB included a set of comprehensive guidelines that included the what to teach, the how to teach, and the why to teach of EFL public education, from kindergarten to Grade 11. Although the guidelines were labeled as “suggested,” it was expected that all public schools would adopt or adapt them in their EFL planning and instruction (MEN, 2016). The policy guidelines highlighted the intricacies in which the documents play a role in how the policy was enacted in different schools.

Researchers and stakeholders have criticized the PNB. For instance, Ayala Zárate and Álvarez (2005) criticized the adoption of the CEFR since “not all Colombian schools have the same physical resources [as in Europe], technology, human resources, and enough governmental economic investment” (p. 15). Sánchez Solarte and Obando Guerrero (2008) also disapproved of standards development without schoolteachers’ participation. They indicated that Colombian schools devoted, on average, only two hours of English instruction weekly, in which students were not all the time exposed to the language, creating unfavorable scenarios for developing English language competences. Finally, teachers’ proficiency continued to be a limitation, as MEN found out in a diagnostic test where 63% of English language teachers in Bogota still had a basic proficiency level (A1-A2), and only 14% had an advanced level (C1-C2) (Sánchez Solarte & Obando Guerrero, 2008, p. 191). Researchers even criticized the limited definition of “bilingualism” to the Spanish-English notion (de Zarate, 2007, as cited in Usma, 2009a).

Two objectives of the PNB are of immediate interest to the present study. First, the reform is framed within the general goal of “promoting educational equality and mak[ing] English language teaching and learning seen as a strengthening tool for the education of 21st-century Colombian students” (MEN, 2016, p. 7). Second, they set as one of their purposes to “ensure . . . an equitable treatment for all the population exposed to exclusion, poverty, and the effects of inequality” (MEN, 2016, p. 26, emphasis in original).

Although various studies in Colombia have critically reviewed the enactment of the PNB (Benavides, 2021; Bonilla Carvajal & Tejada-Sanchez, 2016; Valencia, 2013), the current research study is, to our knowledge, the first study that focuses explicitly on the equality and equity gaps the policy attempts to address.

Capital Building

This study draws upon Bourdieu’s (2006) concept of capital, defined as the intertwined connections between an individual’s cultural values, social networks, economic resources, and social conditions. Capital encompasses the assets individuals possess and value, as shaped by what is valued in the context or field. Bourdieu (1992) acknowledges language as a form of symbolic capital that provides individuals access to materials and educational opportunities. Individuals enrich other forms of capital by gaining access to resources, education, and employment opportunities through their language capital. It is a cycle in which social agents’ symbolic and language capital (English and Spanish bilingualism, in this case) give them access to economic means that individuals use, successively, to invest in their symbolic and language wealth.

The possession of different types of capital also contributes to the homogenization of social groups in distinctive classes (Moore, 2008). Framed by this conceptualization, learning English as an international language is recognized socially in Colombia by its cultural and symbolic value and the economic prospects it potentially provides (MEN, 2014). Learning English is socially perceived as a form of capital by students and teachers, and how it is built through learning opportunities by the participating schools is of central interest to this study.

Previous scholarly work in Colombia has employed Bourdieu’s concept of capital to explore the agency and role of teachers (Guerrero-Nieto & Quintero, 2021), the use of symbolic power to institutionalize discourses around policy (Guerrero, 2010), and critically analyze the ideologies behind EFL policies (Valencia, 2013). We build on these previous studies by employing Bourdieu’s concepts to problematize students’ equal access to language capital when enacting the current EFL policy. Acknowledging that policy is translated, interpreted, and contextualized in various ways in schools (Ball et al., 2012), we explore how Colombia’s current language policy reform—to bridge the equity gap through English language learning—is enacted in public schools. To achieve this, we are guided by one overarching research question and two sub-questions:

How is the National Bilingual Program enacted in three Colombian Grade-5 classrooms?

Research Design

Context

This exploratory, sequential, and mixed-methods study is framed within Colombia’s three approaches to foreign language schooling: non-focalized, focalized, and piloting bilingual. According to MEN (2014), over half of the Colombian public schools (52%) are non-focalized, providing one weekly hour of foreign language teaching in primary education and two hours in high school. Focalized schools provide more allocated hours to foreign language programs (from three to ten hours of English weekly), usually taught by teachers with academic language qualifications. Piloting bilingual schools provide a more rigorous program in which at least 50% of the school curriculum is delivered in English (MEN, 2018). Any school can apply to be either a focalized or a piloting bilingual school, which entitles them to further funding. Nevertheless, political support and leadership of all stakeholders are necessary for successful application.

We selected one non-focalized, one focalized, and one piloting bilingual school purposefully to explore the differences among the schools in terms of (a) the specific policy enactments that occurred across the institutions, (b) the students’ and teachers’ perceptions and views towards foreign language schooling, (c) the teachers’ perceptions towards EFL policies, and (d) the teachers’ backgrounds. We employed three criteria to choose the participating schools: (a) they represented the different English language program structures (i.e., non-focalized, focalized, and piloting bilingual); (b) they were public and offered both primary and secondary education; and (c) they belonged to three different education districts. We use pseudonyms to refer to each school: Belgrano, Santander, and Bolivar (located in low-middle-income areas). We focused on Grade 5 (one per school) as this is the last stage before secondary school (halfway through the students’ primary schooling).

Belgrano School

Belgrano School is a non-focalized institution located in a municipality with 135,000 inhabitants and has approximately 1,980 students and 75 teachers across two campuses. The school provides two hours of English language classes per week as a non-focalized institution. Thus, Belgrano represents the most traditional public school in Colombia. The institution had access to regular state funding for English language initiatives in their school.

Santander School

Santander School is in the state capital with a population of 481,000 inhabitants and has a student body of approximately 1,550 learners and 60 teachers. It is a focalized institution and receives additional funding and resources from the state government to strengthen its English curriculum. Santander offers three hours of English weekly, has an English conversation club, and allows students to participate in bilingual camps with private institutions.

Bolivar School

Bolivar School is in a town of 35,000 people, enrolls about 1,700 students, and has approximately 85 teachers. At this piloting bilingual school, fifth graders take five hours of English classes a week, plus science, arts, technology, and physical education in English. English language teachers with previous experience working in such disciplines teach these classes.

Data Collection Instruments and Participants

An exploratory, sequential, mixed-methods study design was employed to explore language policy enactment in these three Colombian public schools through the sequential use of qualitative and quantitative data to inform subsequent data-collection phases. First, data were collected through student and teacher questionnaires, which were employed to inform the design of student focus groups and individual semi-structured interviews with teachers. Data were collected in Spanish, and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for further analysis. Interviews were translated into English by the first author and then spot-triangulated by two additional native Spanish speakers. Data collection was conducted in the schools between August 2019 and February 2020. Data were collected by the first author (concurrently across the three institutions) and then analyzed by the three researchers.

This study was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 19751), and informed consent was obtained from all the principals. All names used here are pseudonyms.

Student and Teacher Questionnaire

A questionnaire was distributed to students (10-11 years old) in three Grade 5 classrooms and their English language teachers. While the student questionnaire focused on their access to resources (such as the internet, books in English, and opinions towards English), the teacher questionnaire aimed to unpack their professional and academic backgrounds and identify their years of experience and English proficiency level. Thirty-five students (out of 70) from Belgrano, 30 (out of 32) from Santander, and 14 (out of 27) from Bolivar completed the questionnaire. Three Grade 5 English language teachers participated in this study, one from each school. In addition to teaching 22 hours of classes per week, public primary school teachers also work on the committees that make institutional decisions, lead parent meetings, and provide written reports on students’ achievements and behaviour. The participating teachers held permanent positions in their respective institutions: two had graduated from English language undergraduate programs and one from a childhood pedagogy program. Table 1 presents the professional and academic backgrounds of the participating teachers.

Table 1 Teachers’ Professional and Academic Background

| Teacher | School | Professional background | Professional experience in ELT | Self-reported English language proficiency (CEFRL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laura | Belgrano | BA in Pedagogy | Five years | Non-proficient |

| Camila | Santander | BA in ELT MA in Education | 22 years | Independent user (B1) |

| Gloria | Bolivar | BA in ELT MA in Education PhD in Education (1st year) | 14 years | Independent user (B1) |

Note. ELT = English language teaching. CEFRL = Common European Framework of Reference for Languages.

Student Focus Group

Twenty-one students from the three participating schools participated in a 45-minute focus group. The semi-structured interview protocol built upon information collected in the survey and focused on students’ perceptions of (a) teachers’ practices, (b) English language learning, and (c) opportunities to learn English outside the classroom (see Appendix). The headteacher chose students who participated in the focus groups for their willingness to participate and freely share their views and experiences.

Teacher Interview

This study incorporated semi-structured teacher interviews that lasted approximately one hour. The interviews had five areas of inquiry that included questions about teachers’ professional and academic background; their views, adoption, adaptation, and resistance towards their school’s language policies; the institutional support they perceived; and their perception of student challenges and opportunities.

A1 Proficiency Test

A sample of the Cambridge Young Learners English Test (YLE A1 Movers), a standard A1 proficiency test, was administered to each participating student group. This one-hour paper-based test comprises four sections: listening, writing, reading, and speaking. Although the PNB does not implement the test to assess students, it provided an overview of the student’s proficiency for this study. Twenty-eight students from Belgrano, 22 from Santander, and ten from Bolivar completed the test. The tests were marked according to the percentage of correct answers that the students had. The scores calculated were intended to provide a general picture of student achievement on the test.

The sections of listening, reading, and writing were marked twice by a research assistant and the first author of this article. Likewise, the speaking section of the test, administered by the research assistant and the first author, was audio-recorded to be marked a second time. Marks were compared, and whenever there was a difference between the two marks, which was rare, a consensus was reached.

Data Analysis

Given that the questionnaires were collected first, a preliminary analysis provided insights before conducting the student focus groups and individual teacher interviews. Additionally, an initial analysis of the students’ interview responses was helpful when addressing particular aspects during the teachers’ interviews. Data were collected by the first author of this paper, an English language teacher in a Colombian public school. Although the researcher did not know any of the participants personally, he shared the same profession as the interviewed teachers; that is, the participating teachers may have identified the researcher as a peer.

The interviews were transcribed, coded, and categorized using thematic analysis techniques (Saldaña, 2012). Data were triangulated and contrasted, first in each institution and then across the three schools, revealing patterns and inconsistencies. Some of the themes that were coded among the three schools were, for example, “language use in the classroom,” “institutional alliances,” “resistance towards guidelines,” “compliance with the policy,” and “teachers’ agency.”

Additionally, data were analyzed using a thematic approach incorporating individual and systems-level theories. This analysis was guided by a theoretical framework and informed the development of interview questions. The themes from the data were then identified, coded, and categorized according to this theoretical framework. The approach used was based on the work of Braun and Clark (2006). Some of these themes were “language capital building,” “learning opportunity,” and “learning environment.”

Two rounds of thematic analysis were conducted manually. After each researcher coded the data individually, we compared the themes and categories to reveal consistencies and some inconsistencies in our coding process and worked to improve the intra-reliability and inter-reliability (McAlister et al., 2017) of our data analysis. The first and the second data analysis rounds were conducted within a three-month interval, and although the wording of some of the categories and themes slightly changed, these remained essentially the same.

Findings

The findings revealed that inequalities arose from the three distinctive English language schooling approaches which hamper the PNB’s goals that aim to (a) promote equality, (b) make English language teaching and learning the conduit for equipping and developing students for the 21st century, and (c) ensure that the curriculum provides equitable treatment for all student populations (MEN, 2016). The findings of this study further reveal that equitable access to English language learning opportunities was not equally enacted among the three schools. This prevents English from becoming a “strengthening tool” (MEN, 2016), regardless of the characteristics of the schools that students attend. As a result of a lack of “equitable treatment” (MEN, 2016, p. 26) across schools, there were unequal levels of achievement—one of the critical problems that the new policy attempts to address (MEN, 2014).

Unequal Access to English Language Learning Opportunities

Unequal access to English language learning opportunities among the three schools became evident mainly in terms of time: the time each school allocated to English language learning and the time spent using the target language in the classroom. We are aware that the number of hours allocated to English, for example, does not necessarily result in students learning more English and that it is ultimately the quality of teaching that creates learning opportunities and positive learning environments (Rixon, 2013). However, to guide our analysis, we identified three indicators for English language practice: the number of hours allocated to English, the amount of English used in the classroom (vs. L1 use), and English-related extracurricular activities. It is important to note that although the policy documents do not specify whether the classes should be conducted entirely in English, the suggested curriculum, the guidelines for implementing the curriculum, and the student’s textbooks were all published in English. This indicates that, for those who interpret the policy, it implicitly suggests that English be actively used within the classroom.

Belgrano School

When asked about the language employed in the classroom, Laura, the English language teacher, reported that she used Spanish primarily but incorporated some key English words or phrases for instructional purposes or as part of classroom routines. An explanation for the limited use of English in Laura’s classroom—which had been simplified to routine phrases and rarely used for everyday classroom interactions—was due to her lack of confidence in her English proficiency. Laura noted that she preferred to avoid English words to avoid mispronouncing anything. It is worth remembering that although Laura had pedagogical training, this was unrelated to English language teaching.

Laura’s lack of confidence in speaking English silenced its active usage, signaling how English language use was positioned and perceived within her classroom. Students were also asked about the language choices made by the teacher for instructional purposes and their perceived opportunities to use English in the classroom. Luisa, for example, said that the teacher spoke English sometimes but mainly used Spanish. Juan added that he had never heard his teacher speak English, whereas Paula said they used English only to say “good morning” or “goodbye,” but the rest of the class was in Spanish.

The students’ statements corroborated Laura’s description of how English was used within the classroom, suggesting that students’ exposure to listening to, speaking, or interacting in English was limited in this program, and the teacher and students were aware of this. With the recognition of how English learning and use was positioned within the school, Luisa, one of the students, argued that students’ motivation to learn English was severely hampered by the fact that despite being offered English classes, students did not effectively learn the language and, therefore, could not use it to interact. For Sebastian, another student, learning English was only possible by travelling abroad, showing that the students perceived the opportunities to learn English at Belgrano as too scarce. Luisa, for instance, insisted that no one at Belgrano would be able to learn English, and she questioned the rationale behind learning the language if she could not converse in it with others.

With no one to speak English with, there was a lack of motivation to learn and use the language, influencing and shaping how English language learning was positioned within the classroom. In this regard, Belgrano did not have a learning environment that promoted English learning, and while there was a space to learn it, there were limited opportunities for active English language use and practice. Indeed, Belgrano students perceived that using English and being exposed to it in the classroom was vital for improvement. When asked what they would do differently if they were the English language teacher, one student, Juan, replied that he would give the whole class in English so that the students could learn more. Paula, for instance, answered that she would give a scholarship to students so that they could study English outside their school.

Santander School

Santander allocated three hours of English per week. According to the students and the teacher, English was the primary language used in class. Camila, the English language teacher, reported that all the instructions and commands were in English but that using Spanish was necessary when explaining complex instructions.

When students were asked about the role of Spanish in the class, Leyla commented that the teacher used Spanish to ask for attention, tease, and scold. Likewise, Jeremy expressed that he enjoyed speaking in English with his classmates because it made him look intellectual in his own eyes. These statements suggest that English was commonly used in the classroom, and students not only used it to interact with the teacher and participate in class but also to speak with peers.

In addition to the three regular hours of English, Santander hosted “extended English classes” and an English conversation club. These classes were mandatory, and students were evaluated in these sessions. While not directly enacting the guidelines of the PNB, Santander’s English language curriculum had been designed on the school’s funding structure (a focalized school), which provided additional learning opportunities for students. This suggests that the enactment of the PNB, mainly focusing on equitable access across schools, is complicated by the funding structures of English language programs in Colombia.

Bolivar School

In contrast to Belgrano and Santander, Bolivar was a piloting bilingual school that offered five hours of English instruction and taught the subjects of science, technology, and physical education in English. These practices were very different from those of the other two schools. All subjects were taught by teachers who graduated from English language teaching programs and had knowledge of the discipline. Gloria, the classroom teacher, stated that she attempted to deliver all her teaching in English but switched to Spanish if her students did not understand her instructions. The students confirmed that English was the primary language employed in class. Brenda, a student, reported that the teacher only used Spanish to explain something students did not understand in English. Mateo added that all the topics were in English, and her teacher encouraged students to use them whenever possible. Violeta, another student, said she considered herself and her classmates lucky to have good English classes at Bolivar because, according to her, other children could not study English because they did not have teachers who could speak the language.

In short, Bolivar offered 13 hours a week in English (out of the 25 hours of their curriculum), English was commonly used in the classroom, and students were encouraged to use it whenever possible. The time spent actively using English across the three schools was an evident inequality that shaped students’ access to it inside the classroom, which afforded varying opportunities for English language capital building. Not only did Bolivar School allocate more hours of English instruction than its counterparts, but the teacher and her students appeared to use the language more often in the classroom. In contrast, and as we have described, while participants at Santander reported that teachers and students occasionally used English in the classroom, those at Belgrano noted that students had limited exposure and opportunities to use English. We believe these inequalities are an organic consequence of the three policy enactments, exposing the complexities of PNB when schools have such varying funding structures.

Unequal Level of English Achievement Among Grade 5 Students

The Pedagogical Principles and Guidelines of the PNB outline the English language proficiency level that students should develop each school year. According to the document, “Students in Grade 5 should achieve an A1 proficiency level under the CEFR” (MEN, 2016, p. 31). Therefore, in addition to exploring the allocation of time spent in learning and using English within each school program, we wanted to explore the different levels of achievement among students by administering the YLE test. This is significant, as at the time of writing this paper, no existing studies had collected data on the achievement of Colombian primary schools concerning the goals set by the PNB. Although only three classrooms took the test, it sheds light on the different levels of achievement across English language enactments in the country.

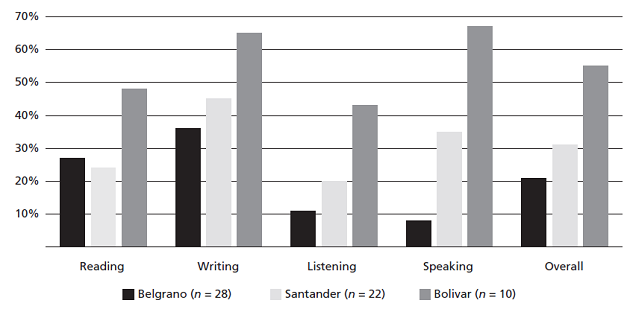

Figure 1 shows the percentage of correct answers students scored in each section and the test overall. Rather than a more in-depth statistical analysis, percentages provide an overall picture of the variation in achievement across the schools. We acknowledge that further statistical analysis is required to understand and make sense of the relationships between student achievement, language skills, and school funding structures. Based on the Cambridge website guidelines for interpreting results, four students from Bolivar achieved an A1 proficiency level (the suggested proficiency for fifth graders according to the MEN), and no student from Belgrano or Santander obtained the necessary score to be considered an A1 proficient language learner.

Figure 1 corroborates our analyses of the qualitative data in that, despite the aspirational introduction of the national policy to address equality, the three language programs are not the same. Instead, they differ in both the opportunities for language exposure and use and their achievement outcomes.

Figure 1 also shows that the most remarkable differences among schools are listening and speaking, the critical components of spoken interactions and communication. This disparity may be due to differences in exposure to English and opportunities to use it within classrooms. Reading, on the other hand, is the language skill area in which schools performed similarly. Alongside an emphasis on developing students’ English language reading and writing in schools (Zabala-Vargas et al., 2019), another reason might be that when language teachers do not feel confident in their listening and speaking skills, they tend to focus more on developing reading and writing competencies among their students (Van Canh & Renandya, 2017).

This study’s qualitative and quantitative data suggest that the three programs are unequal regarding language exposure, use, or outcomes. Despite the goals of the PNB to promote “educational equality” (MEN, 2016, p. 7) through English language teaching and learning and to provide a curriculum that allows for “equitable treatment” (MEN, 2016, p. 26), we argue that the enactment of the curriculum is shaped more by the funding structures in place (e.g., non-focalized, focalized, and piloting bilingual) than it is by policy guidelines. This is not surprising given that these three schools were purposefully chosen to explore the enactment of three different language programs. However, the findings highlight that because the schools reflected similar socio-economic backgrounds, how they were funded had a powerful impact on how they enacted the PNB rather than the PNB itself.

Discussion

Bilingual policies in education theoretically demand the provision of opportunities for language capital building. These reforms attempt to create spaces where cultural, linguistic, and symbolic assets are transformed and exchanged through intricate networks within and across fields (Bourdieu, 1986). Nevertheless, when schools fall short of providing access to opportunities and spaces to create and exchange language capital, inequalities in language learning and levels of achievement arise between institutions. Moreover, it is possible to determine that access to funding may shape the schools’ ability to provide opportunities and how much time students are exposed to and use English within the classroom. It is agreed that language learning reform should provide teachers with professional development opportunities to gain confidence in their abilities (Van Canh & Renandya, 2017) and help address currently-held beliefs about language and language learning (Barnes, 2021; Budach, 2013; Mellom et al., 2018; Zuniga et al., 2018), given that teachers can create opportune spaces for language learning. This is particularly important as it has been shown that teachers’ language choices influence students’ language use (see Ballinger & Lyster, 2011) and students’ access to capital-building opportunities (De Wilde et al., 2020; Fhlannchadha & Hickey, 2019).

Enactments of policy, by nature, result in differing interpretations and implementations of the same policy, mainly due to the diversity of teachers’ beliefs about language and language learning (Hornberger & Johnson, 2011; Zuniga et al., 2018) and how funding is applied (Butler, 2007; Nguyen, 2011). Although the PNB aims to provide equal access to English learning and encourages equal outcomes through the homogenization of the curriculum, the methodologies of teachers, and the assessment of students, the current funding structures towards this aspiration raise inequalities of learning opportunities. In many ways, the current funding structures thwart the successful enactment of the curriculum. When access to funding is not configured based on the needs of students, schools, communities, or regions, bilingual policies risk perpetuating learning inequalities. In other words, the distribution of human resources, materials, and learning resources that the PNB proposes ultimately influences unequal outcomes across institutions. Although there are chances for equal access to opportunities, these would need to be provided through needs-based funding and redistribution of human and learning resources, which is non-existent with the current policy.

Although bilingual abilities entail more than language proficiency, such as cognitive organisation (Bialystok, 2011), enhanced executive control (Bialystok et al., 2009), multicultural competencies, and tolerance to ambiguity (Dewaele & Wei, 2013), the MEN largely determines the success of the national language policies in terms of English language proficiency (MEN, 2014). We acknowledge the complexity of bilingual skills, and the administration of the YLE test aimed to provide a general overview of students’ achievement levels and compare it with the policy goals. Notably, despite enjoying more English language learning opportunities than most mainstream schools in Colombia, four students from Bolivar—and no students from the other schools—achieved an A1 proficiency level. The MEN should not only widen its conception of “successful bilingualism” but also the instruments to assess it. If students’ proficiency continues to be considered the primary outcome to evaluate the success of language policies in public schooling, other forms of achievement (e.g., openness to foreigners, tolerance towards difference, multicultural knowledge) might be obscured, and reforms might be perceived as “unsuccessful.”

Conclusion

This study reveals that current funding structures hampered the enactment of the PNB. The study exposed the differentiated enactments of the English language curriculum guidelines and the unequal opportunities for learning and achievement. Moreover, we identified the complexities in language policy enactment. Given that English language learning is a conduit for human capital building (MEN, 2016; Murray, 2020), providing a set of curriculum guidelines for language instruction is just one step towards equalizing opportunities and achievement among students. There also must be the equal and equitable provision of financial resources to schools if the equality/equity agenda is to be meaningfully addressed.

Despite its contribution to the literature on policy enactment and its entanglement with school funding, this study is limited in scope. While the three participating teachers met the study’s inclusion criteria, the participating students were not recruited based on inclusion or exclusion criteria but because they were students in the participating teachers’ classrooms. In addition, data collection was limited in scope due to being part of a dissertation project. As a result, further research is needed to not only expand the number of participating schools and corroborate and further interrogate the findings of this study but to provide more quantitative analysis on student achievement, examining the relationships between different schools, language skills, and the allocation of language instruction. In addition, future research might consider that some students, institutions, and regions may need more access to language capital than others.