Introduction

Communities have been recognized as groups of people that share common interests and live in particular areas called territories. Each community member possesses meaningful knowledge in different fields, either agriculture, cooking, mechanics, medicine, or other areas that make them unique. Lemke (1995) defines communities as “systems of doing, of social and cultural activities or practices, rather than as systems of doers, of human individuals per se” (p. 93). In this view, communities provide local knowledge constructed through time and transmitted by generations. As Corburn (2003) states, “local knowledge can also include information about local contexts or settings, including knowledge of specific characteristics, circumstances, events, and relationships, as well as important understandings of their meaning” (p. 421). All the knowledge held by communities constitutes a fundamental source for teaching and learning since it can bridge the gap between schools and students’ realities, provoking more significant learning.

By exploring funds of knowledge, students and teachers can find possibilities to see their ways of living and territory, thus re-signifying who they are and their community. In addition, using mechanisms such as dialogue journals to verbalize and communicate their perceptions and understandings of their communities paves the way for authentic interactions, the actual use of language, and the possibility to see others, thus establishing relationships that transcend the distance and possible cultural and place differences. Considering these possibilities, two teachers from various locations and contexts joined forces to interact and build community knowledge by using dialogue journals and exploring their students’ communities and funds of knowledge.

This study explores how students from rural and urban schools construct community knowledge by delving into their families’ funds of knowledge and exchanging information about their community using dialogue journals. Students were stimulated to write about their family and community knowledge and share their perceptions and understandings of what they explored with other pals. This experience allowed students to see their territory, share culture, and learn from others’ experiences. Teachers and students can make connections between classroom life and the world outside “when schools, families, and community groups work together to support learning, children tend to do better in school, stay in school longer, and like school more” (Henderson & Mapp, 2002, p. 7).

This article reports the findings of an action-research study aimed at answering the following research question: How do students from rural and urban educational institutions construct community knowledge by exploring their funds of knowledge and using dialogue journals?

Theoretical Framework

This study drew on community-based pedagogy (CBP) principles that regard the community and the knowledge families hold as sources for curricular construction. Sharkey (2012) defines CBP as the “curriculum and practices that reflect knowledge and appreciation of the communities in which schools are located, and students and their families inhabit” (p. 11). It is an asset-based approach that emphasizes funds of knowledge as starting points for teaching and learning.

Funds of Knowledge

Funds of knowledge are based on the premise that all students and families are valuable and accumulate knowledge, skills, and cultural resources (Moll et al., 1992). Funds of knowledge build a bridge in which teachers connect with students’ sociocultural, linguistic, and intellectual backgrounds, developing funds of identity (Marquez Kiyama & Rios-Aguilar, 2017). By exploring funds of knowledge, we attribute such value to students’ knowledge drawn from their life experiences which can be nurtured and strengthened with teaching practices beyond the classroom walls. As Cummins (1996, as cited in González et al., 2009) states, “our prior experience provides the foundation for interpreting new information. No learner is a blank slate” (p. 5).

In this vein, learning is a social practice that should be connected to students’ lives, local histories, and community contexts (González et al., 2009), which is where funds of knowledge become a fundamental pillar in CBPs. These two intertwined frameworks provide a platform for teaching and learning. According to Lastra et al. (2018), “[CBP] involves the knowledge of the local communities, beliefs, constructs, and perceptions that all the people who belong to that community hold and share through everyday contact” (p. 211). In addition, Cooper and Levin (2011) also argue that CBP is an action-oriented method to help teachers learn more about their students’ cultures, especially their homes and communities. When CBP is rooted in funds of knowledge and is used as a framework for classroom practices, teachers and students become more aware of their social responsibility. Community knowledge nourished by the family is central to curriculum and pedagogy (Freire & Macedo, 1987). In this respect, Murrell (2001, p. 6) states that schools should collaborate with parents and the community to provide classroom practices that involve their reality, experiences, and communities.

Exploring funds of knowledge in classrooms brings positive connections that stimulate learning and engage students in a more significant process. First, the connection with new learning content related to their context that at the same time supports their academic improvement (Subero et al., 2017). Second, the teacher-student connection (Barton & Tan, 2009) and students’ empowerment (Esteban-Guitart et al., 2019) in which they feel their voices are heard by their classmates, who may share the same background or not, drawing on knowledge that is meaningful for the student. “The knowledge produced by students offers educators opportunities to learn from young people and to incorporate such knowledge as an integral part of their teaching” (Giroux, 2004, p. 66).

Community Knowledge

Community knowledge, also known as local knowledge, entails the richness of understandings, values, beliefs, customs, and traditions that each human community has created through time. This local knowledge is not a product constituted by the beliefs and practices of the past [but] is a process of negotiating dominant discourses and engaging in an ongoing construction of relevant knowledge in the context of [people’s] history and social practice (Canagarajah, 2005, p. 13).

This local knowledge is the basis for the construction of new knowledge. We cannot ignore that this knowledge has a changing character, subject to the new changes that continue appearing around communities (Canagarajah, 2005). Local knowledge entails all the wisdom elders have, constituting a treasure trove of information beyond schooling because it is steeped in a community’s context. Usually, it is knowledge acquired through survival. As such, it is part of the intangible heritage of families and communities; it is the accumulated knowledge of many generations and covers a wide diversity of context-based (rather than school-based) topics. Local knowledge is mainly “orally transmitted (from generation to generation) and is largely undocumented; it is based on experimentation, adaptation, and innovation and driven by the pragmatic demands of everyday life” (Šakić Trogrlić et al., 2019, “Conceptualising Local Knowledge” section, para. 7).

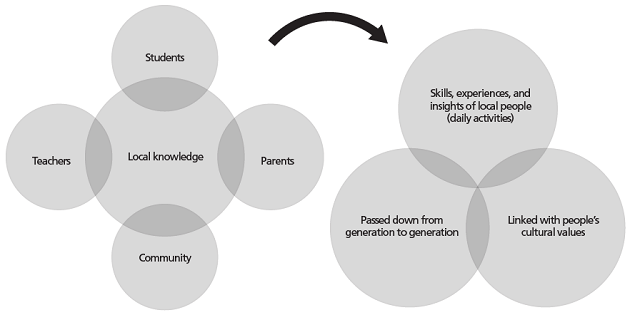

In this regard, local knowledge provides insights into how communities interact with their surroundings; it is context-bound and locally situated (Canagarajah, 2005). In other words, “local knowledge is the human capital of urban and rural communities” (FAO, n.d.). Local knowledge is present in people’s discourses, reactions, and beliefs, showing how people face and respond to living conditions. In a rural community, local knowledge also represents the way people produce (farming) and trade (income) their food. It is immersed in the social environment (inhabitant interactions) between family, friends, and neighbors. In conclusion, as Figure 1 illustrates, local knowledge entails the experiences, conceptions, and beliefs the members of a community hold.

In recognition of this wealth of knowledge, schools must build bridges that allow significant connections between local knowledge and the curricular demands of educational institutions. When the curriculum brings students’ backgrounds and social contexts into the classroom, the learning process becomes more authentic, facilitating the creation and integration of different types of knowledge.

Dialogue Journals

Dialogue journals are written conversations between two people, one-to-one, like pen pals. Dialogues can be done “live,” as quick exchanges during class, or as “takeaways,” longer, more leisurely letters written and answered at the correspondents’ convenience (Daniels & Daniels, 2013, p. 100). The benefits of dialogue journals for students are broad: Students feel motivated and invited to constantly communicate their thoughts, feelings, and opinions to others based on topics they propose. Moreover, using dialogue journals in class allows teachers and students to participate in private written conversations to share feelings, understandings, experiences, and other academic activities (Hail et al., 2013). In our study, dialogue journals served as a bridge to establish connections and build relationships between rural and urban students to exchange real-life interactional conversations. Anderson et al. (2011) acknowledged the importance of “forming positive student-teacher relationships” (p. 270), especially in middle school when social disengagement becomes popular. This pedagogical tool was crucial to developing trust and confidence in teenage students, who typically reject writing and are shy about expressing their feelings.

Dialogue journals allow students to express themselves and help them improve their language skills at the lexical and grammatical levels. Additionally, the discursive and communicative aspects of writing can be enhanced. Students became more confident with people and their language abilities, and their willingness to write increased. Finally, they pointed out that they could express opinions, felt heard, and had a critical view of world issues. For our research, these insights guided the intention of motivating students to communicate their perceptions and understandings of their communities.

Method

This study was framed within a collaborative action-research design, which entails a deep inquiry into one’s professional interactions and finding ways to understand and improve teaching practices (Riel, 2019). Similarly, collaborative action research “provides a path of learning from and through one’s practice through a series of reflective stages that facilitate the development of progressive problem solving” (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1993, as cited in Riel, 2019, p. 1). In this respect, our role was to plan the instructional design based on the study’s objectives and the school curriculum. The teachers who carried out the plan were in constant dialogue with each other to follow up on the students’ progress, the plan’s course, and the data collected throughout the implementation.

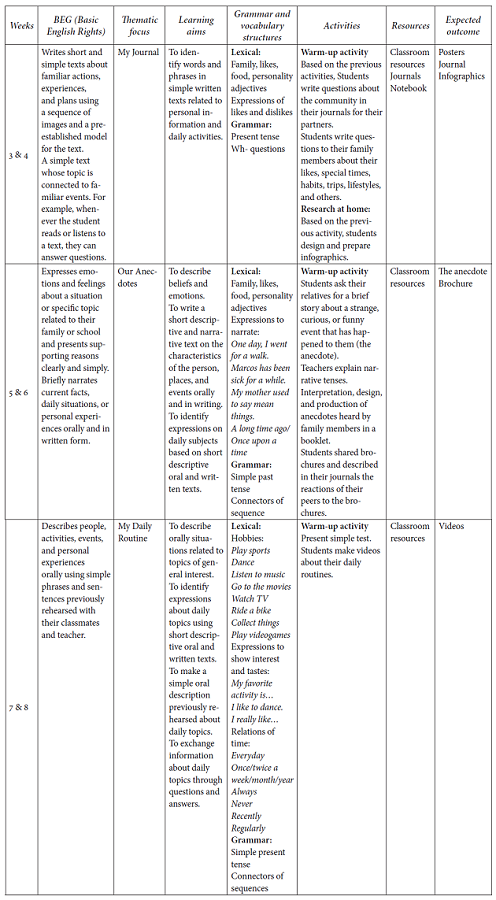

A curricular unit was designed (see Appendix A) to integrate the realities of the students, their communities, and their funds of knowledge into the curriculum. The objective was to make this knowledge visible and to open interaction spaces through dialogue journals, provoking the development of meaningful literacies for students.

Context and Participants

This study occurred at two Colombian public schools: one in an urban area (the city of Ibagué, the capital of the Department of Tolima) and the other in a rural town (in the same Department). The participants volunteered to participate, and their parents signed a consent letter after being informed about the study. The study was carried out in two phases. A group of 33 seventh graders (average age: 13-14 years) from the urban school participated in the first phase. Teacher L from the urban school explored dialogue journals to encourage students to talk about their neighborhoods. As the results obtained in this first moment exceeded expectations, Teacher L shared her experience in an academic setting in which Teacher K, motivated by the experience and in agreement with Teacher L, decided to expand the study by exchanging students’ dialogue journals and exploring knowledge of both participants’ communities (rural and urban); that is when the second phase of the study took place. Two groups participated in this second phase: 19 sixth graders from the urban school whose average age range was 10-11 years (of the 19 participants, one was 12 and another 15). The second group comprised 18 eighth graders from a rural school whose average age range was 12-13 years (only one student was 14). Teacher K taught this group. The students were selected considering their positive responses in English class and their interest in the study. For ethical reasons, participating students were numbered and given a code based on whether they were from a rural school (RS) or an urban school (US). For instance, Student 1 from the rural school was coded as RS-Student 1.

Data Collection Process

At the beginning of the implementation, a needs analysis (see Appendix B) was applied to the participants in the study’s first phase to explore their opinions about the English class and their preferences regarding methodology and class activities. This instrument revealed students’ feelings and expectations of the class and provided information that guided Teacher L to use journals to explore students’ neighborhoods and give them authentic motives to write and exchange information with her. This was the first approach to students’ voices. Afterward, the teacher designed and administered a survey and a questionnaire to collect their opinions about writing in English and using journals in class.

Students’ positive responses to the use of dialogue journals guided Teacher L in planning the first phase of this study. Students mapped their communities and participated in different activities in English class. They had to write about their communities and families in journals they designed following personal criteria, and the students exchanged the journals with the teacher every Friday. From the beginning, Teacher L agreed with students that the journals were to be read just by her. The improvement in students’ writing and responses was evident, with more accurate use of English, longer messages, and positive reactions to the teacher’s responses.

Based on the results obtained in the first phase, and after an academic dialogue with Teacher K, both teachers decided to work together to further explore the students’ funds of knowledge by using dialogue journals in the second phase. Both teachers planned their pedagogical intervention in a curricular unit (see Appendix A). It included the moments and all the activities students carried out throughout the pedagogical implementation; the curricular unit exhibits the community events students explored, the actions and the different assignments they completed, and the family and community knowledge they explored.

In the second phase of the study, data were collected through students’ artifacts (e.g., posters, infographics, and brochures) and interviews with students’ relatives and community members. These instruments allowed us to identify and analyze students’ funds of knowledge and perceptions of their community. Another instrument was the students’ dialogue journal, in which they wrote about topics related to family and personal anecdotes, feelings, understandings, and experiences. Students from both schools shared their journals once a week within their groups and got responses and comments from their pals. Both teachers wrote narratives about the most spontaneous moments of the implementation and their reflections. Besides these instruments, a focus group, guided by Teachers L and K, was held via Zoom at the end of the process to explore students’ reactions and the most significant lessons drawn from the experience. Students from both schools participated and had the chance to meet for the first time.

Data Analysis

The analysis of results followed the principles of the grounded theory approach. First, the initial coding resulted from a careful reading of data from each instrument, which is a “process of analyzing qualitative text data by taking them apart to see what they yield before putting the data back together in a meaningful way” (Creswell, 2015, as cited in Elliott, 2018, p. 2850). This initial coding expressed in marginal notes provided preliminary themes. Afterward, we used memo-writing to study the data and codes in new ways, and we interpreted data analytically and identified emerging patterns to develop theories about them (Hull, 2013). Then we proposed tentative categories by exploring the theoretical sampling (Charmaz, 2012) to refine those preliminary categories into saturated categories (Coyne, 1997). All this process led to five preliminary categories:

Characterizing community funds of knowledge: Unveiling cultural richness,

Rediscovering family as firm upright support for students’ communities,

Understanding local knowledge derived from community experiences,

Bearing out emotions regarding students’ community, and

Re-signifying writing.

After exhaustive analysis and reviewing of data, we observed the possibility of merging Categories 1 and 2 since they shared elements that could be repetitive when presented individually. Likewise, in Categories 4 and 5, the results from one category were implicit in the other. Then, three categories were finally stated.

Data were validated using member checking, a technique that allows researchers to increase the authenticity, goodness, plausibility, and credibility of the inquiry they conduct (Carlson, 2010) and to understand in a better way the students’ experiences and the significance of those experiences (Candela, 2019). This makes it more than a validation tool but also a reflective experience. Member checking also “consists of taking data and interpretations back to the participants in the study so that they can confirm the credibility of the information and the narrative account” (Laryea, 2020, p. 93).

Findings

This section describes how participants constructed community knowledge as they explored their funds of knowledge. These ways have been grouped into three main categories: (a) Characterizing Community Funds of Knowledge and Building Significant Connections, (b) Building Confidence by Understanding Local Knowledge as a Result of Seeing and Sharing Community Experiences, and (c) Re-Signifying Community Knowledge and Bearing out Emotions.

Characterizing Community Funds of Knowledge and Building Significant Connections

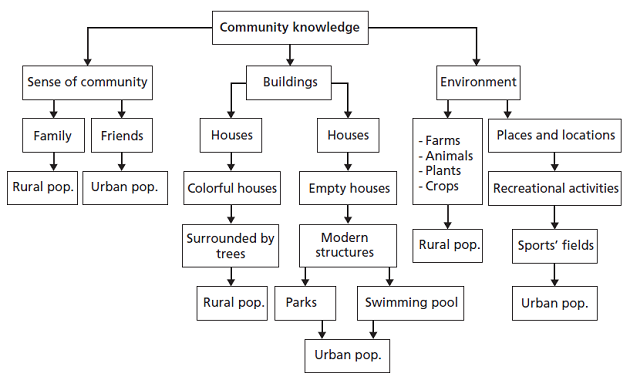

This category reports a deep analysis of participants’ views and insights regarding the concept of community. Significant connections were evident in students’ reports and class discussions. Firstly, students connected the community with the territory; the geographical space was linked to ways of living, houses, locations, families, animals, pets, individuals, and activities, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Students feel proud of the natural environment they have, as a student claims in the following excerpt: “There is my house, it is big and . . . family big, my house has many streams, this is my pig, there are many animals” (RS-Student 1, community poster). There is a strong association between the territory and the richness of the community; its plantations and representative crops define its territory. The students’ houses were places of encounter, places to share. The territory is also associated with the people the students relate with. “My house is the place where I spend most of the time, with my family…my friends are a great company and distraction when I am depressed” (US-Student 3, community poster).

Secondly, the concept of community was connected with others’ ways of living. Students focused the descriptions of their communities on their friends, sports fields, and zones of entertainment. People around them are an important part of their lives and are present in their idea about the community.

Thirdly, for the participants, the community is connected with culture, beliefs, customs, and ways of living. Mapping their communities made them pay close attention to what surrounded them; walking around and taking photographic evidence opened the door to see their territory and all they moved and lived in. By seeing their community, participants could portray the richness of their territory represented by the individuals and the activities carried out in that place. Thus, the concept of community for these students was linked to individuals, animals, and the social, economic, and religious activities in that specific community. As two students state:

The celebrations in my town are very beautiful, people from all over the country go, and we celebrate the mountaineer’s day. (US-Student 1, infographic)

On family vacations, we go out every Sunday and eat something, we go to the church every 15 days, the vegetable cream is the special food of the house…family festivities are celebrated by going for a walk…with my brother we use the ball; Jerson, my brother, is the funniest person. (US-Student 2, infographic)

Exploring funds of knowledge allows teachers to see students and connect with their sociocultural, linguistic, and intellectual backgrounds (Marquez Kiyama & Rios-Aguilar, 2017). Using funds of knowledge also connects learning to students’ lives and the community they represent (González et al., 2009). Teachers are invited to rethink the course content, negotiate meaning and curriculum with the students, involve families in class activities, and generate community projects that bring social proposals. In this vein, dialogue journals became instruments to verbalize students’ perceptions, illustrate their contexts, and provide a clear vision of who they are, where they come from, and their understanding of family. The following excerpt illustrates the student’s point of view about the experience of sharing dialogue journals:

Dear friend, thank you for sharing everything in your life, your adventures, the place where you live, what you told me through is very nice, I would like to go one day to meet you and you will show me how beautiful Guasimal is. Where you see, me it would be easy to get to know and that you were the one to show me the landscapes that Guasimal has and I hope that we continue to communicate and that could be your friend and then thank you very much for all friends and that you and your family are very well. From your friend: RS-Student 2. (Journal entry)

It is evident how dialogue journals provide meaningful ways of communicating ideas when students write for real audiences and get authentic responses. Thus, writing turns into meaningful social practice.

Building Confidence by Understanding Local Knowledge as a Result of Seeing and Sharing Community Experiences

Students understood their funds of knowledge when they could depict their daily events, family activities, and relationships with different family members. Discovering each other’s world brought such significant meaning for the participants. As one of them describes: “It is interesting to see the way [students in rural areas] live, to see their daily routine, the difference between living there and in the city; it makes us value what we have, and that is something beautiful” (US-Student 1, focus group).

Interacting with members of their families, neighbors, and other actors in their communities helped students appreciate the lifestyle of others and make connections between their personal and family experiences. In this respect, one student states: “Uh...I learned about what my partner liked, I learned about the places she had visited, I learned about the things she liked to do, religion, her favorite subjects” (US-Student 2, focus group). We can observe that authentic communication flows without any linguistic restriction when students have significant topics to write or talk about. Students felt confident talking about their family and community, and language served as a vehicle to communicate what they felt identified with. Feeling confident to express, respond, react, and share results from having authentic topics to dialogue. The exploration of funds of knowledge lets students make their families and communities visible.

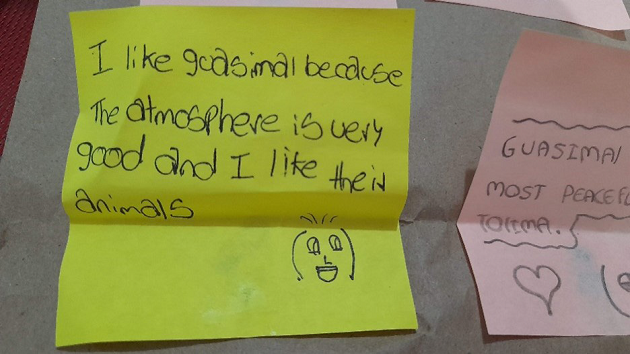

At the same, their context and the knowledge that individuals hold about a specific space become meaningful when such knowledge is associated with feelings of tranquility and peace. Even for those living in the city, nature becomes valuable because it constitutes a territory of serenity and color. Valuing nature is rooted in the ability to discover the relationship between the countryside, the animals, and the activities of the community members. Appreciation, acknowledgment, and empathy amid diversity were manifested in the dialogues, and the expressions participants in the city used when referring to their partners in rural areas, and vice versa. All this community knowledge observed and discussed by students throughout their class activities allowed them to explore ways of describing, narrating, and reacting, turning all these communicative intentions into authentic content for the English class:

I like the poster of your community because it is very quiet here, because there are many animals and a connection with nature. I call my attention to your community because in the place you live in it is very quiet and there are not as many cars as in the city, the animals, crops, and rivers that you have are very cool. (US-Student 4, dialogue journal)

Visiting local knowledge which is locally situated (Canagarajah, 2005) paves the way for contextualized teaching and learning, which makes explicit connections between the class activities and materials and the local knowledge students hold. These connections provoke authentic interactions and let students open themselves and gain confidence when expressing their perspectives, emotions, or reactions because this knowledge becomes their capital and the hallmark of their identity (FAO, n.d.).

Dialogue journals in class allowed students to tell their activities to others and react to the differences between one area and the other, to find meeting points and characteristics that make them unique. Furthermore, students became aware of their cultural richness, their traditions, and the joy of sharing them with other people, as Figure 3 shows.

Re-Signifying Community Knowledge and Bearing out Emotions

This category aims to reveal all the emotions that surfaced in the students while exploring their communities and exchanging journals. They narrated their stories and reported on the different elements they could re-signify when observing their community and exploring the knowledge of their families, friends, and neighbors. These feelings and perceptions are grouped into four big ideas.

Enjoying and Strengthening the Sense of Belonging

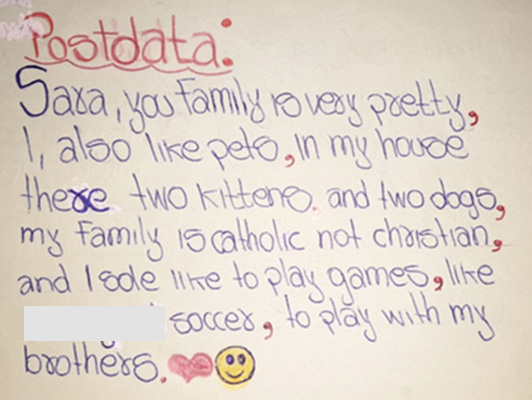

Exploring their communities and interacting with their members served as an eye-opener to discover the beauty of their territory and all the wisdom their families hold in their activities. Learning about rural and urban communities made them feel proud of their territories and broadened their perspective of the other’s community. Students embraced their surroundings, natural resources, backgrounds, traditions, values, typical food, and lifestyle. In this respect, one of the participants states (see also Figure 4):

Well...I really enjoyed sharing with you...here my partner is eh...it was nice to share everything we liked...what we liked to do during the holidays with our family, to know a little about ourselves...it was very interesting, it was very nice eh...to see how...to know how to value people, that was like the message that got to be the hardest, eh? to know how to value what we have and thank you very much for sharing with us, that was so nice. (US-Student 5, focus group)

Acknowledging Others

Comments written in the dialogue journals as reactions to the information participants exchanged made visible feelings of empathy, admiration, interest, and curiosity in students from rural and urban contexts. Their comments and reactions are the results of acknowledgment and appreciation of their environment; this is evident through positive comments that magnify the place they come from:

Dear student, I thank you for having shared your life with me, even if I don’t know you, I hope you are a person with a wonderful future and hopefully our teacher will agree so that one day we can visit your institution. (US-Student 6, dialogue journal)

Emotions Play a Relevant Role in Learning

Besides the feelings of excitement, there is once again the happiness of sharing the experiences of a community with other students from alternate contexts, the enchantment to know other realities, the expectation of a subsequent encounter, the enjoyment of meeting new people, the joy of having a voice and reflecting in the company of others on the differences of each community, and above all, the hope, at the end of the project, to meet the other participants face to face. A student describes her feelings in the following excerpt:

Ehhh...well...I felt very happy, the truth is that when the teacher told us that we were going to interact with other classmates eh...I felt very happy because it is a nice way to get to know people...also...as I said...a lot of reflection....because, before, I didn’t have the same classmate but I also had another classmate, because with the notebooks and the life experiences they told us were eh...sometimes very nice, sometimes very sad and like...that made you nostalgic and at the same time happy...you went like a carousel of emotions so...that was...that was something very nice. (US-Student 4, focus group)

This project operated as a bridge of interaction between both environments, where all the participants not only reported but also learned about the practices of other students by bringing class their funds of knowledge. Gratitude and best wishes to all were the rewards for the great work.

This classwork type helps English teachers realize that emotions play a relevant role in teaching and learning. It is necessary nowadays to humanize education and understand that we work with individuals who are not only brains but hearts. Emotions can either trigger learning or turn into an obstacle. It is valid to bring teaching practices in which students have the possibility of experiencing and expressing what they feel. Bearing out emotions opens options to connect students with the classroom, and language becomes more significant because exploring communities awakens all the feelings we represent and hold, and all this together allows students to make their voices heard, as Figure 5 illustrates.

Discussion

Undeniably, exploring funds of knowledge and using dialogue journals to exchange experiences and knowledge provided relevant information about how teachers can benefit from students’ backgrounds to construct knowledge in class. Murrell (2001) highlights the importance of supporting teaching-learning activities with a community-based practice that makes language significant for students while visiting and seeing their surroundings. He also argues that a community teacher “possesses and works to build on the knowledge of culture, community, and identity of children and families as the core of his/her teaching practice” (p. 2). The different practices that the students had throughout the implementation enabled them to map their communities, listen to the stories of their families and neighbors, and explore the knowledge they had regarding specific activities. This gave participants real possibilities for communication and authentic scenarios of interaction. By visiting their communities and inquiring about their cultural and economic activities, the students discovered themselves, and we, as teacher-researchers, got to know and understand the world of our students with whom we shared a tremendous amount of time. In addition, most of the teaching decisions were enlightened by all the knowledge students shared in class.

Exploring students’ communities helped not only the participants but the teachers as well to find significant resources in the community. Family activities and knowledge became sources for curricular construction in which students established authentic connections between the target language and their realities and context. Gruenewald (2003) claims that individuals are the product of a lifetime of environmental and cultural education embodied in our experiences of places. It is a must for schools to see those experiences and connect them to class to be explored, analyzed, and valued in such a manner that education would not be a core of content isolated from the students’ world but a place where students can learn from their realities and make significant connections at school.

Dialogue journals to share information and experiences that resulted from the students’ community exploration provoked “good conversations” (Bahadur Rana, 2018) in which students from both schools could express themselves and see their own and others’ experiences in a two-way interaction. This allowed the students to bring their experiences into the classroom to establish connections with what they were learning at school, creating new knowledge (Bahadur Rana, 2018).

Participants discussed various family-related topics and issues with their peers as openly as they did with their teachers at the beginning of the research. At first, we thought students would be unwilling to share personal information with their peers. However, this was not the case, and the participants enthusiastically wrote about their families and personal lives in their artifacts. The participants felt equally respected, appreciated, and supported in both pairings, which would support Atwell’s (1987) ideas that the writer’s need for response can come from various sources. Most of the students’ entries developed their appreciation for their communities and others, the value of their chores at home and on farms, as well as school duties, and the love of their family as a central part of their life.

Conclusions

The concept of community makes sense for students when they can observe the places they are part of. Students belong to places, live with people, and inhabit communities that hold the knowledge that can be explored and analyzed in class to make connections between the school curriculum and the realities of students. This study provides insights for teachers in rural and urban areas to see the richness around them, which can be used as a pedagogical and curricular resource.

Students expressed their motivation, confidence, and engagement to participate in meaning-making writing opportunities with peers in their dialogue journals. Exploring funds of knowledge and communities of students provided reasons to write about topics that come from their daily life and actual events. Dialogue journals facilitated communication and provided authentic scenarios of interaction.

The process of constructing community knowledge by exploring funds of knowledge provided connections that were significant for students. These connections went in three directions: First, connections with content tied to the student’s culture. Seeing the community paves the way for authentic interactions, uncovering the richness of the place and the people that live in that specific space, which permeates teaching decisions and opens the door for authentic language practices. Second, connections between teachers and students: The former becomes a sort of researcher of the student’s context and community by exploring their lifestyle, customs, and economic and social activities with students. Third, connections with pals to willingly share information and respond to each other’s entries. Using dialogue journals, students pictured their understanding of their community with words and developed authentic conversation cycles that included spontaneous responses. Student-student dialogue journaling engaged them to write in English and made them feel respected, appreciated, and supported. Indeed, the reactions that emerged were always optimistic; the experienced emotions were happiness and excitement of doing research at home with their families, joy and hope to interact with other people different from their context, and inspiration to do future projects where their families are the base of the research.

In general, local knowledge is a valuable resource for teaching and learning, as people can explore their daily happenings and share their community knowledge, which is full of funds of knowledge that could be used in classrooms to engage families and turn that knowledge into significant input, worthy of being incorporated into the curriculum. The issue of rethinking and re-signifying the role of communities in Colombian education is of central importance since little attention has been paid to the student’s previous experiences and backgrounds, the affective dimension in class, and the creation of safer classroom environments that boost students’ learning (García Gutiérrez & Durán Narváez, 2017). This might be done by becoming educators who empower “students with a profound trust in people and their creative power” (Freire, 1968/2018, p. 24).