Introduction

In the European and Spanish contexts, the teaching and learning of foreign languages have become a priority due to their contributions to intercultural communication and social cohesion. As a result, the development of plurilingualism, which aims at ensuring that pupils develop communicative competences in two foreign languages at the end of secondary school (European Commission, 1995), has been the determining factor of the reforms carried out by educational administrations. One of the most significant measures adopted has been the introduction of bilingual sections, in which—following the content and language integrated learning (CLIL) approach—a foreign language is used to learn and teach content and language (Coyle et al., 2010). The core feature of this approach is the concept of integration: It intertwines content and language (Custodio Espinar, 2018). Thus, this integration has a double focus: Language learning is incorporated into content classes, and the subject content is used in the language learning class. Therefore, CLIL goals are content, language, and learning skills (Mehisto et al., 2008).

The introduction of the CLIL approach in different educational contexts has been accompanied by an extensive scientific production which has been particularly interested in students’ learning outcomes, primarily the linguistic domain (Navarro-Pablo, 2021; Pérez Cañado, 2018), and in the methodological developments of the approach (Coyle et al., 2010; Marsh et al., 2015; Mehisto et al., 2008). As for teachers, the research focus has been on their training with an emphasis on the need for teachers to have not only good proficiency in L2 but also in-depth knowledge of the methodological and didactic foundations of bilingual teaching (Pavón Vázquez & Ellison, 2013; Pérez Cañado, 2016). Some authors highlight the difficulty of adapting university degrees to the training demands of this new educational reality because of the slow pace at which this type of change occurs (De la Maya & Luengo González, 2015). In addition, the rapid growth of bilingual programmes in Spain meant that many teachers were faced with bilingual teaching without adequate training on the methodological changes that adopting a new curriculum based on integrating language and content areas implies. This resulted in a “great degree of uncertainty, and many experienced teachers have suffered from frustration and started to question their professional identity” (Breeze & Azparren Legarre, 2021, p. 26).

This last observation raises a recent area of interest: the affective dimension of learning and teaching due to including the affective, cognitive, and motivational processes in learning theories (Hascher, 2010). Emotions are not only present in our daily lives, but they also become visible in every teaching-learning process so that, as Schutz and Lanehart (2002) point out, “an understanding of the nature of emotions within the school context is essential” (p. 67). This new consideration of emotions has been driven by the diversification of their theoretical foundations, facilitating the study of emotions from different perspectives and methodological proposals, increasing knowledge about the role of emotions in education, and opening new ways to investigate feelings. In language teaching and learning, the role of emotions, as Méndez López (2020) notes, has gained importance in the last decades. Emotions can either help or hinder the foreign language teaching and learning process, as they influence learners’ and teachers’ perceptions, behaviours, and learning outcomes (Simons & Smits, 2021, p. xiii).

The above highlights the importance of discussing and examining the affective dimension in educational contexts, specifically emotions. For this reason, this article presents the results of a qualitative study that combines both fields of study: emotions and teachers, explicitly investigating the affective dimension of CLIL preservice teachers.

Literature Review

The Affective Dimension of Teaching

The role of teaching involves a considerable deal of emotional workload, both due to the sensitivity required towards the emotions of others and because of what is involved in managing one’s own and others’ emotions to ensure the quality of the relationships in the school context.

Since the 1990s, attention to teaching and teachers, in general, has increased. The growing interest in this area is due to several reasons. Firstly, emotions are an essential part of the daily teaching activity of teachers (Badía, 2014). Secondly, emotions provide relevant information about teachers’ characteristics, which is necessary to improve teachers’ lives and instructional quality. Thirdly, many studies recognise the importance of the emotional aspect in teaching (Schutz, 2014). Finally, emotions favour cognitive processes.

Golombek and Doran (2014) mention that “emotion, cognition, and activity continuously interact and influence each other, on both conscious and unconscious levels, as teachers plan, enact, and reflect on their teaching” (p. 104). In addition, as Cowie (2011) states, “how teachers deal with emotions can have a great impact on their personal growth, and the kind of emotional support that they receive from their colleagues and institution can be a major factor in their personal development as a teacher” (p. 236). Likewise, as Frenzel et al. (2015) highlight, teacher’s emotions “have been shown to be critically important for the quality and effectiveness of classroom instruction and are highly relevant for teachers’ psychological well-being” (p. 1).

In the classroom, teachers show a variety of emotions, from enjoyment to anxiety or anger. According to Cubukcu (2013), the emergence of these emotions can be due to several causes: achievement of the objectives, teaching requirements, knowledge about the subject matter, relationships with colleagues, classroom discipline, curriculum constraints, lesson demands, or language management. The frequency and intensity of emotions vary among teachers depending on their personal characteristics, the group of students they teach, their academic subject (Frenzel et al., 2015), and how they understand the challenges encountered in teaching. Likewise, the appropriateness of emotional experiences is highly dependent on the context and is based on fundamental institutional and cultural values, norms, and practices (Hagenauer & Volet, 2014).

Researchers have been interested in the emotions of in-service and preservice teachers and their role in constructing their professional identity. During this initial training, the practicum is recognised not only as one of the core parts of education programmes (Zabalza Beraza, 2016) but also as the most influential in the personal and professional development of preservice teachers (Timoštšuk & Ugaste, 2012). During the practicum, preservice teachers face some concerns and challenges which provoke emotions and feelings about teaching focused on different areas (Badía, 2014): personal perception of oneself as a teacher, the working environment, the teachers’ perception of aspects related to teaching activity and strategies, appropriate forms of expression in the classroom, and adapting teaching to the student’s knowledge level, to name a few.

Emotions of English Language and CLIL Teachers

Although emotions influence the teaching process and determine—for both experienced and preservice teachers—the construction of their professional identities (Zembylas, 2004), there has been little interest in research in this field, especially in the CLIL domain. Even though the introduction of bilingual teaching has posed a considerable challenge for teachers who are not native English speakers and have to cater to students with low proficiency in the language of instruction, scarce research has been conducted on these topics. As Breeze and Azparren Legarre (2021) emphasise, this situation can, at best, “jolt teachers out of their comfort zone, and at worst, it may lead many highly experienced professionals to doubt their own competence and feel insecure about their role in the classroom” (p. 28), with negative repercussions for the teaching/learning process and the teachers’ own identity.

Emotions of English Language Teachers

Emotions in the specific context of English language teaching have been studied from two perspectives: those that students experience and those the teachers, through their professional performance, can stimulate if they are positive, or try to prevent, if they are negative (Dewaele & Dewaele, 2020). The second perspective refers to the emotions that the teacher experiences during professional practice. Recently, as De Costa et al. (2018) indicate, the increase in attention regarding language teacher emotions has turned this area into “the proverbial newest kid on the SLTE (second language teacher education) block” (p. 401).

Concerning the second perspective—the most relevant to the subject matter of this article—a common aspect in research examining emotions and English as a foreign language (EFL) teaching is “a somewhat negative tone to the findings” (Cowie, 2011, p. 236). In the theoretical review carried out in her research, Cowie (2011) cites teachers’ language deficiencies, lack of time, unwanted classroom observations, and negative relationships between colleagues as sources of negative emotions, especially anxiety and stress. Also, institutional problems can lead to anger and a state of persistent frustration and bitterness. Finally, Cowie notes how these emotions can negatively affect the teachers’ ability to reflect on their teaching. The effects can have “long-term consequences” on both the teacher and learners (De Costa et al., 2018). However, other studies highlight the positive emotions experienced by language teachers. The results of Heydarnejad et al.’s (2017) study show that enjoyment followed by pride—both positive emotions—are the most frequently mentioned by the teachers in their sample, for whom negative emotions are experienced in a much lower percentage. In any case, as metaphorically represented by Gkonou et al. (2020), foreign language teaching can be an emotional rollercoaster, a challenge for which not all teachers are equally well prepared.

As far as preservice or novice teachers are concerned, some studies have also explored the emotions they experience, either during the practicum or in their first year of teaching (Ocampo Martínez, 2017; Wolf & De Costa, 2017). Lucero and Roncancio-Castellanos (2019) state that emotions, on those first occasions when prospective teachers face a teaching situation, contribute to the teachers’ survival and enduring engagement in a practicum, and those emotions are mainly triggered by the preservice teachers’ reflection on their teaching performance. Most studies show a superiority of negative emotions over positive ones (Méndez López, 2020). However, they also show how positive emotions serve as a counterbalance to help prospective teachers deal with negative experiences of the practicum (Nguyen, 2014) as a basis for new pedagogical models that allow these teachers to develop their reflexivity or negotiate emerging challenges (Wolf & De Costa, 2017). The process of adaptation, in which there is a readjustment between what they expect and what they experience in the practicum regarding emotions and situations, helps them to “reshape their incipient identity as language teachers” (Méndez López, 2020, p. 25).

Emotions of CLIL Teachers

Studies of emotions affecting in-service CLIL teachers are more recent and less extensive. They will be discussed with those focusing specifically on preservice teachers, whose life emotions have an important role.

Only a few studies, to our knowledge, have been interested in analysing teachers’ emotions in this new professional context. Pappa et al. (2017) studied how emotions influence the transformation and maintenance of teaching identities of both novice and experienced teachers by considering that “the experience of both positively and negatively tinged emotions are important for CLIL teachers’ self-understanding, well-being, and job satisfaction” (p. 81). Their results revealed that the teachers’ prevalent negative emotions were feelings of rushing and frustration, derived from the study plan, time issues, questioning themselves as competent professionals, or their students’ negativity towards the approach. Conversely, the most common positive experiences were satisfaction and empowerment, resulting from teachers’ and students’ involvement, learners’ progress, and the feeling of being qualified to teach CLIL or from exercising their profession. In a later study, Pappa (2021) asserts that positive and negative emotions have developmental potential, as both experiences can make the pedagogical identity more receptive to change, methodological innovation, or professional development.

Breeze and Azparren Legarre (2021), in a study with in-service training teachers, highlight how, in the case of CLIL teachers, their professional identity is threatened as they lose a clear idea of what kind of teachers they are—language or content teachers—which gives rise to negative emotions. This, together with confusion about their role in the classroom, undermines their daily satisfaction.

Gruber et al. (2020) examined the factors contributing to CLIL primary teachers’ well-being in Austria. These included the conviction about CLIL, the positive relationship with the pupils, and feelings of comfort in the teaching environment. Conversely, negative beliefs related to CLIL, linguistic confidence, negative experiences with the pupils’ parents, high workload, the extra time needed for bureaucratic tasks, or lack of support may negatively affect teachers’ well-being.

As mentioned above, the language requirements of CLIL teachers can be a significant emotional challenge that can impact teacher identity development, as language proficiency is one of their main concerns during their training (Mearns & Platteel, 2021). Some non-native English-speaking teachers may need more self-confidence in their language skills. Horwitz et al. (1986) mentioned the existence of foreign language anxiety and the negative consequences this could have on teaching. As Mercer et al. (2016) point out, it can be a challenge for teachers to be unable to predict the path a conversation class will take or to express themselves in a foreign language with the same resources they would have in their mother tongue. These limitations affect not only their self-confidence, identity, professional competence, and well-being but also represent “a particular risk for teachers who find themselves teaching their content subject(s) through a foreign language (such as CLIL teachers)” (p. 217). In addition, the complex nature of both responsibilities and tasks in a foreign language content teaching context may be susceptible to increase stress. The results of the study by Aiello et al. (2017), carried out with teachers in Italy preparing to become CLIL teachers, revealed the existence of linguistic anxiety and low self-perceived proficiency in English, which would be related to low willingness to communicate.

In the same vein, Torres-Rocha (2017) focuses on how the teachers in his sample feel about the language requirements associated with implementing the National Bilingual Programme in Colombia and how it affects their teachers’ professional identity. Positive feelings about the programme include challenge, achievement, hope, and expectancy, while negative feelings include limitations, frustrations, scepticism, and disappointment towards this policy. In his conclusions, Torres-Rocha notes that these feelings “demonstrated to be conflicting factors influencing teachers’ construction and reconstruction of their identities” (p. 52) and highlights other external and internal factors that influenced teachers’ professional identity.

Based on this theoretical framework, this paper aims to investigate the emotions of students from a master’s degree in bilingual education for primary and secondary school teachers during the internship period. The research aims were:

Method

According to Bisquerra Alzina (2014), qualitative research reflects, describes, and interprets the educational reality in depth to understand or transform this reality. Resorting to a qualitative and critical methodology helps inquire into the thinking of future teachers (Sandín Esteban, 2003). Therefore, to achieve this study’s aims, we chose a qualitative research method, which allowed us to understand the nature of the emotions experienced by preservice teachers and what teaching in CLIL classes implies for them (Arizmendi Tejeda et al., 2016).

Context and Participants

The study context was a university in the southwest of Spain that offers a master’s degree program to address the training needs for implementing bilingual experiences in Spanish compulsory education. The master’s syllabus is structured around four modules: the theoretical and practical bases of bilingual education, the linguistic needs of bilingual teaching in English, the practicum placement, and the master’s thesis. The five-week teaching practicum placement aims to enable future teachers to apply and complement the knowledge acquired in their academic training. The External Internship (as the practicum is called) consists of six credits and represents a 120-hour stay in a school, 25 hours of individual work, and five hours of seminars to reflect on the experience and connect theory with practice.

The participants were 19 students from the master’s during the 2020-2021 academic year. The ages ranged from 22 to 36, averaging around 24. In addition, 15 participants were women, whereas four were men. Most of the participants (17) taught in primary school during the internship period without any teaching experience beyond the internships of the degree course. Of these seventeen students, three had experience in bilingual and non-bilingual schools, whereas only two had experience in one or the other kind of school, not in both types. In all cases, the experience was less than one school year. Although the required linguistic accreditation is a B2 level of English—according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001)—10% of the participants had a C1 level, higher than that required to participate in bilingual education programs.

Data Collection Instruments

This exploratory, descriptive study was carried out using a questionnaire. Since we did not find previous work addressing this particular issue, the questionnaire was elaborated, taking as a reference the interview guide of Arizmendi Tejeda et al. (2016), the questionnaire of Tachaiyaphum and Sukying (2017), and our own questions. In addition, it was subjected to expert judgment, after which some questions were included, and others were removed or redefined.

The research tool is mixed and includes some initial sociodemographic aspects as well as 20 questions. Thirteen are closed-ended and collect information on critical elements of emotions; the remaining questions are open-ended to gather additional data on the emotions experienced and to obtain a deeper understanding of the participant’s feelings. The questionnaire was completed in Spanish to facilitate participation, but the participants’ answers have been translated into English for publication purposes.

The questionnaire was sent to the participants through a Google Forms link to their emails. We obtained written consent, and the anonymity of the participants was always guaranteed.

Data Analysis

Once the data were obtained, we conducted a thematic content analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), organising the information into different tables. To analyse the data and to identify emotions, we consider “emotion talk” and “emotional talk” in participants’ responses, in terms of Bednarek (2009). Emotion talk is understood as an apparent reference and naming of emotions (e.g., love, joy). In contrast, emotional talk is understood as language indirectly related to an emotional experience, which does not need to be identifiable. Both are considered discursive strategies rather than a form of representation of the actual internal affective state of the speaker (Galasiński, 2004).

Results

Our first objective aims to know the emotions experienced in teaching non-language subjects and their causes. We can state that preservice teachers reported diverse feelings while interacting with and teaching their students during the practicum placement.

Positive Emotions

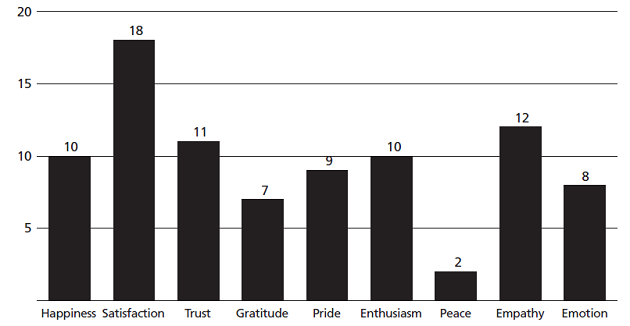

As shown in Figure 1, which shows the frequency of positive emotions experienced by the participants, the most prevalent positive emotions were satisfaction and empathy, which are mentioned 18 and 12 times, respectively. Other emotions were trust, happiness, enthusiasm, and pride, with similar values experienced by more than half of the participants. On the opposite side, peace is the least felt positive emotion (only reported by two participants).

Nearly all participants were satisfied to see how well the students assimilated the subject, even though it was in a foreign language, which evidenced feelings of adequacy as they responded to what was asked of them and competence as they managed to teach the content successfully. Moreover, satisfaction is also the emotion experienced when they were able to develop their classes as CLIL teachers:

When things went well, you used the content well, and the sequence was a success, you were overcome with a feeling of satisfaction, as on many occasions, you worked double and triple to achieve good results in this type of teaching. (Participant 15)

This participant is satisfied when the didactic intervention responds to the expected planning, especially when its preparation demands time and dedication.

Based on the participants’ comments, we can argue that teachers feel more satisfied when they transform theory into practice successfully. This is evidenced in their students’ positive learning results, which reinforces the feeling of satisfaction, both towards the teaching practice and the choice of profession.

Secondly, participants showed empathy when students had difficulty understanding what was being explained. When teachers frequently interact with children, they can detect whether they grasp the information through gestures. One participant pointed out that this leads to teachers putting themselves in the students’ shoes. Finally, they agree that if teachers empathise with the students, a positive bond is established because the students fully trust the teacher, which may even lead them to improve their academic performance.

Regarding the remaining positive emotions, happiness and trust stand out. The first stems from seeing the children absorb and learn what is explained and when they pay attention. The second one is experienced when the participants feel able to teach in another language using the knowledge gained during the master’s course, as well as with the acceptance and welcome of the teaching staff.

Negative Emotions

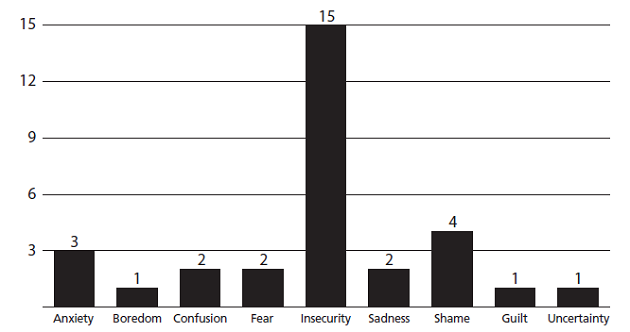

Among the negative emotions, insecurity ranks first, being mentioned in almost all the answers:

I felt insecure due to my lack of experience in bilingual sections and my lack of mastery of some subjects. (Participant 12)

I did not have CLIL training or know much about Social Sciences. (Participant 3)

I felt some insecurity and fear about having to deal with a bilingual lesson . . . This is because of foreign language use and all it entails when teaching students and promoting content learning. (Participant 16)

I felt insecure because I did not know if I were teaching correctly. (Participant 7)

As the comments reveal, insecurity derives from several factors, such as the verbal use of a language that is not one’s own or poor command of both the subject matter and the CLIL approach. Likewise, lack of students’ attention, unexpected results, and not knowing whether the language is appropriate to the student’s age, knowledge, and level of English are other causes of insecurity.

Teachers might also feel anxious when they want to transmit something but find it difficult due to their low proficiency in the foreign language, which may make teachers perceive that they are losing control of the class.

Secondly, the participants mentioned shame or fear of ridicule when they do not answer as expected since they are supposed to know the answers and when students correct the teachers’ pronunciation mistakes. It also seems to happen when explaining the topics, as preservice teachers feel that some children are looking out for the mistakes they might make. These emotions are followed by confusion, uncertainty, fear, and sadness. Finally, boredom and guilt are the least experienced by the sample (see Figure 2). In general, preservice teachers reported positive emotions more frequently than negative ones.

Among the variables that have influenced the emotions felt, we can mention the fact of having done the internship in lower or higher grades, which can facilitate or hinder the implementation of the approach, mainly due to the student’s age. Another variable is the non-linguistic subjects taught, as Natural and Social Sciences are the subjects that contribute more to the teachers experiencing emotions, particularly negative ones. Lastly, teaching experience is another of the variables mentioned since its absence causes fears due to a perceived lack of practical knowledge.

Finally, the last aspect deserving special mention is the mentor’s attitude. If the tutor facilitates preservice teachers’ integration within the daily teaching work, they will become accepted and develop their acquired skills and knowledge. A negative attitude on the part of the tutor can lead preservice teachers to reject teaching a particular subject or even their profession.

Emotion Regulation Strategies

Regarding the second objective, which aimed to identify the emotion regulation strategies employed by preservice teachers to manage emotions appropriately, we used Gross and Thompson’s (2007) emotion regulation model as an analytical framework. The most notable strategy used is cognitive reappraisal, mentioned by 11 respondents (out of 19), consisting of thinking about what is uncomfortable to find the best possible solution. Thus, it can be inferred from the participants’ answers that once the fundamental importance of the events has been analysed, they try to look for alternatives to improve situations of anger with the children, situations of frustration at checking that students do not fulfil the desired objectives, or even the loss of control due to lack of attention: “I tend to use cognitive reappraisal, especially in situations where you get angry about something that you rethink and it’s not such a big deal. So, before I say something, I put it in perspective” (Participant 2).

The second most frequently employed strategy is modifying the situation (seven out of the 19 participants), which consists of seeking ways to prevent conflict so that everything is more cordial and bearable. The remaining strategies involve, on the one hand, attentional deployment, that is, avoiding the problem because of an unwillingness to face it or even thinking about more pleasant situations or events; and, on the other hand, situation selection, that is, choosing what is more favourable to regulate emotions. Finally, the suppression strategy involves holding back negative emotions, such as anger, because they harm the students and avoiding similar unwanted behaviours that children can imitate.

As it can be seen, most strategies are antecedent-focused and not response-focused since teachers modify emotions before they occur, except in one case in which a participant indicated that she alters emotional behaviours after the feelings have emerged. In addition, all participants believe that how emotions are managed influences the classroom climate, and, at the same time, most of them (16 out of 19) recognised the difficulty of regulating them adequately. Thus, the consequences can be both positive and negative.

From the participants’ remarks, it can be deduced that the attitude of teachers when managing their emotions can be decisive in creating a pleasant and optimal atmosphere in the classroom. Thus, the inability of some people to find an adequate response to control negative emotions can lead to increased discussions between teachers and students and, therefore, chaos. Participant 15 explains the consequences of inadequate regulation of emotions: “Well, loss of control of the situation, loss of credibility, uncomfortable situations, and, in general if you don’t have an emotional balance, you lose control. We are slaves of our emotions until we get to know them.”

Likewise, Participant 8 adds how the teachers’ emotions can, in turn, impact emotions in students: “The classroom environment can be affected, influencing the children’s own emotions and interest as well as the control of the class.”

This negativity can affect the student’s academic performance and even their behaviour towards the teacher, leading to demotivation, insecurity, loss of control, and children’s possible rejection of the subject. On the other hand, when there is an adequate response to a problem, the teacher and the students create a climate of harmony, transmitting security and confidence, which is turned into learning success.

Discussion

The main findings of the research indicate that being a teacher is emotionally demanding. Preservice teachers reported 18 emotions, including nine positive and nine negative ones. The most frequently experienced positive emotion among them was satisfaction—similar to the study by Pappa et al. (2017)—but empathy, happiness, and confidence were also mentioned. In turn, the most frequently described negative emotion was insecurity, followed by confusion and shame, emotions related, among other issues, to the linguistic demands of these programmes, as revealed in studies by Horwitz et al. (1986) and Mercer et al. (2016).

Although prior studies on preservice teachers’ academic emotions have shown that positive emotions are as frequent as negative ones (Pekrun et al., 2002), our outcomes indicated that positive emotions were reported more frequently than negative ones. The fact that one type of emotion—positive or negative—is experienced to a greater extent than others is not a question that has offered unanimous results in the studies carried out, especially those on EFL teachers, since although our data agree with those obtained by Heydarnejad et al. (2017), they are opposed to those reviewed by Méndez López (2020), which show the prevalence of negative emotions over the positive ones. Concerning the causes giving rise to emotions, our results concurred with other studies (Poulou, 2007; Swennen et al., 2004) in the sense that students are the primary source of positive emotions. The findings also support the stance of Malderez et al. (2007) in considering these positive and negative episodes linked to high expectations of the teaching practice.

Therefore, this study highlights the “social nature” of teaching (Zembylas, 2005) since teachers’ emotions seem to depend on pupils’ behaviour and the quality of the teacher-student relationships. These factors can sometimes enhance the teacher’s positive experience or transform initial positive emotions into negative ones (Boiger & Mesquita, 2012). Besides, the data also indicate evidence of emotional transfer (Hagenauer & Volet, 2014). For instance, participants reported that if students failed because they did not understand what was being explained or because of other reasons, they felt empathy and sadness. On the contrary, learners’ achievement made both learners and teachers happy. This is what Clark et al. (2003) refer to as “empathic emotions,” which originated from the “contagious” nature of emotions (Fischer, 2007).

Likewise, there are differences in the non-language subject; the course taught, the teaching experience, and the internship tutor’s attitude, which is consistent with the findings of the study by Brígido et al. (2010).

Regarding the strategies employed to regulate emotions, when cognitive revaluation prevails, teachers are committed to not being influenced by indifference but, on the contrary, facing problems and looking for solutions that lead to conciliation and creating a relaxed atmosphere. This research shows that while positive emotions can be a means for the entire educational community, negative emotions can hinder collaboration and learning. CLIL, due to its flexibility and versatility, allows one to acknowledge and experience a range of emotions (Pappa et al., 2017). Specifically, the time and support invested in responding to CLIL curriculum goals and teaching practice are two issues that must be reconsidered. Our findings highlight that these preservice teachers noted that implementing CLIL in the school requires large amounts of lesson planning and teaching time, as it involves a particular language focus. Teachers spend a long time choosing the appropriate content, designing activities, and adapting and preparing materials (Tachaiyaphum & Sukying, 2017). Therefore, all participants agreed that CLIL is not easy to implement as it is time-consuming (Mehisto et al., 2008) and requires much effort from the teachers. Hence, teacher collaboration becomes essential (Guillamón-Suesta & Renau Renau, 2015).

Finally, as far as teacher training is concerned, participants believed that they need proper training with the help of specialists to become qualified CLIL teachers, that is, to be trained in terms of emotions, language, cooperation among content and language teachers, and knowledge about the CLIL approach to cope with any circumstances that they might experience in the classroom. Results also revealed that preservice teachers need oral English skills training as they have problems communicating in class efficiently because they are not proficient in the language. They also claim that despite having received training on the approach in the master’s, they still find CLIL difficult to implement. As mentioned by Çekrezi (2011), it is convenient to start training preservice teachers at the university level through workshops, guided discussions, or reading circles (Pappa et al., 2017).

Conclusions

The findings of this study highlight the affective dimension of teaching in CLIL. Research of emotions in teaching non-linguistic subjects through CLIL can provide data to make teachers aware of the importance of their emotions and emotional vulnerability and improve teacher training so that they can know their emotions in depth and know how to control and self-regulate them. Negative emotions are often an obstacle to the teaching process of different disciplines. Therefore, the challenge is transforming these emotions into positive ones through strategies that contribute decisively to students’ progress and learning.

Emotions are an integral part of CLIL teaching; therefore, they are present within the teaching activity (Zembylas, 2004). Preservice teachers need to acknowledge the power of their emotions as they shape the student’s learning and the classroom environment and directly influence emotions. These teachers devote significant amounts of time to preparing lessons, and sometimes they forget their happiness and well-being, as evidenced by the high burnout rates often seen in the teaching profession (Evers et al., 2004). Therefore, preservice teachers must acknowledge their emotions for their student’s well-being and themselves. Hence, teacher training programmes should provide prospective teachers “with the self-regulatory and socio-emotional skills needed to manage their own levels of stress, emotions, motivation, and general professional well-being” (Mercer et al., 2016, p. 225), being this one of the main implications of our research. Future teacher training should instruct teachers in strategies of affective regulation that will allow them to manage their emotions adequately. Seminars during internships can be the perfect moment to connect theory with practice and to make the teachers’ emotions visible, share and reflect on them. Developing micro-skills (appropriate emotional expression, regulation of emotions and feelings, coping skills, and self-generation of positive emotions; Bisquerra Alzina, 2009) will provide preservice teachers valuable tools to manage and regulate their emotions in CLIL contexts.

However, this study has some limitations. The sample and context are limited: All respondents belonged to the same master’s, and their placements were mainly in primary education. Therefore, extending the study sample to include more participants and preservice teachers from other contexts and different levels of education would be valuable. Also, it would be interesting to diversify the instruments used, including interviews, for further studies to focus on some of the aspects highlighted in this study. Another research line could be to deal with the strategies for regulating emotions in classroom management and to delve deeper into how the teacher’s emotions influence students.

In conclusion, being a CLIL teacher requires solid disciplinary, linguistic, and methodological training and psychological preparation that allows these teachers to face the emotional challenges and changes in their professional identity demanded by the CLIL teaching context.