Introduction

English language teachers, who specifically adopt English as a foreign language (EFL) policies, provide valuable information about the constraints or accomplishments involved in implementing successful or unsuccessful EFL policies. Hence, increasing interest has been in describing EFL teachers’ challenges as they interpret, enact, or resist policy discourses. In Asia and Europe, several authors have addressed teachers’ agency and its influence on teachers’ activities in the classroom (Hamid & Nguyen, 2016; Liu et al., 2020; Priestley et al., 2012; Verástegui Martínez & Úbeda Gómez, 2022).

Although foreign language education has undergone numerous reforms in Latin America over the last few years (Cronquist & Fiszbein, 2017), research that addresses the specific actions carried out by teachers at the micro level in response to language curriculum reforms still needs to be explored. In the case of Colombia, a significant body of literature addresses the relationship between EFL policy and stakeholders’ adaptations (Araque Cuellar, 2022; Le Gal, 2018; Miranda, 2021). However, there is still limited knowledge in varied contexts where the curriculum was implemented about how teachers specifically coped with the challenges of EFL policy reform.

In 2016, the Colombian Ministry of Education (MEN, for its acronym in Spanish) issued the Basic Learning Rights and English Suggested Curriculum (ESC) for middle and high school (Grades 6 to 11 in the Colombian school system), addressed to English teachers, education secretaries, and schools (MEN, 2016a, 2016b). Working as a complementary plan to support curriculum development and language teaching at state schools, the ESC proposes English learning goals influenced by elements of peace, health, environment, and democracy (MEN, 2016b). Likewise, the ESC states that teachers possess curricular autonomy to analyze and adapt each element within its suggested scope and objectives (MEN, 2016b).

Although some studies have described the experiences of public-school teachers when implementing the reforms derived from the adaptation of new English language policies (Araque Cuellar, 2022; Quintero Polo & Guerrero Nieto, 2013), none of them has inquired into the influence of the ESC when adopted in Colombian EFL classrooms.

We believe the exercise of teachers’ agency can only be described by analyzing teachers’ decisions and the reasons behind their action patterns, described in detail in their own oral and written narratives. This study explored these aspects as we interpreted how each teacher developed their own framework for action. This, in turn, provided varying results based on how teachers enacted the ESC for high school. Although the curriculum being implemented was the same, the uniqueness of each participant teacher provided a stance on how their agency influenced curriculum implementation. The analysis could also conclude convergence and divergence across the three participant teachers.

Literature Review

Agency is the ability to evidence responsiveness to situations conceived as problems within the present and influenced by past and future orientations (Biesta & Tedder, 2006; Emirbayer & Mische, 1998). This ecological notion of agency describes how an individual acts considering paths that influence development, decisions, and actions. This perspective of agency addresses the actions performed rather than the qualities or aspects waiting to be awakened in people (Priestley et al., 2015).

This study takes this ecological notion of teacher agency as the primary construct to address agency theory. We adopted a model of teachers’ agency put forward by Priestley et al. (2015). This model, also known as the Chordal Triad of Agency, describes the development of teacher agency within three dimensions: (a) iterational (past orientations); (b) practical-evaluative (present orientations), and (c) projective (future orientations).

The relationship between teacher agency and policy adaptation within EFL teaching reflects a significant connection between teachers’ adaptation of policy discourses and classroom practices. Recent years have witnessed an increase in new learning curricula in various contexts, so teachers are expected to take roles that reflect the policies in their teaching practices. This view considers the role of teachers as an indicator of successful or unsuccessful EFL policy implementation (Goodson, 2003; Hamid & Nguyen, 2016; Nieveen, 2011; Priestley et al., 2011). This shift in responsibility from the macro (policymakers) to the micro level (policy actors) results in a critical discard of the duty shared between the two levels.

A different perspective by Priestley et al. (2012) describes the responsibility of teachers when they engage in policy adaptation as an opportunity to exercise their professional agency. Teachers are usually given autonomy in teaching practices rather than deprofessionalized by imposed methods and institutionalized teaching procedures. Constraints, change, and activism within classroom life can foster agency development in teachers. Therefore, teachers’ adaptation to the EFL policies also results from the interplay among teachers’ perceptions of the policy discourse, motivations, and the contextual elements fostering or hindering their professional practice.

Teachers engage in dialogues between their paradigms and the outer world to construct a consistent guideline for policy adaptation (Hamid & Nguyen, 2016; Sannino, 2010). Teachers’ individual practices display a certain level of variation based on a teacher’s capacity to interpret policies, and transformation of teachers’ practices at the micro-level occurs as they exercise their agency to enact the new policy discourses. Hence, the process of EFL policy adaptation begins with policy writers (macro level), moving towards the role of researchers and communities (meso level), and finally being reshaped by teachers and students at the micro level. The last few years have seen emerging local studies addressing policy actors’ adaptations and teachers’ agency development at the classroom level in Colombia (Fandiño-Parra, 2021; Gómez Duque, 2020; González, 2007; Guerrero & Camargo-Abello, 2023; Mosquera Pérez, 2022).

The unique view on each teacher’s policy interpretation explains why some teachers successfully adapt it while others fail. Teachers adjust the policy in their work setting to respond to the constraints or enablers in policy discourse. Hence, the actions and decisions of teachers might restrict the school’s methodology and ethos (Hamid & Nguyen, 2016; Liu et al., 2020; Robinson, 2012).

Similarly, teachers’ agency makes a difference in students’ learning outcomes. A mismatch between students’ cultural background and curriculum expectations meets at the micro-level, and the teacher’s activities play a fundamental role in responding to it. Teachers’ mediation is a tool to transform policy discourse into what can be defined as performative action or agency work in the classroom context.

In Colombia, policymakers have traditionally promoted a top-down approach to policy writing, dismissing that teachers’ work lies at the core of policy implementation (Ayala Zárate & Álvarez, 2005; Cárdenas, 2006; González, 2010). This is reflected in the way policies have been designed and implemented. Language policies in Colombia do not start at the core of reforms implemented by teachers (from the bottom-up) or informed by contextual information that nurtures how the policies should be designed, written, and published; instead, some authors argue that policy discourses in Colombia follow a bureaucratic model (top-down) that has institutionalized teacher’s practices with few considerations of their role in a variety of contexts (Correa & Usma Wilches, 2013; de Mejía, 2011). In addition, Hernández Varona and Gutiérrez Álvarez (2020) state that the nature of education in Colombia remains distorted as it regards teachers as policy consumers rather than policy creators, which deprofessionalizes teachers’ activities and leaves little space to navigate the impact of teacher’s work within policy implementation.

Therefore, considering that research on teacher agency development in EFL contexts is a novel trend in Colombia (Hernández Varona & Gutiérrez Álvarez, 2020), the current study analyzed three teachers’ agency development to contribute to the understanding of how state school teachers in the country enact or resist policy discourse implementation, specifically, the ESC.

Method

This study followed a qualitative case study research design (Creswell & Creswell, 2017; Denzin et al., 2006), which allowed us to study the issue of teacher agency by analyzing three cases in a bounded system (participant teachers in the state school system).

We were external to the research context. Author 1 was a master’s student when the data were collected and is currently a university teacher. Author 2 is a graduate professor. Both researchers participated in data collection and analysis.

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, lesson observations, and teachers’ narratives. The interviews allowed access to the teachers’ interpretation of the policy (ESC) as well as further descriptions of the nature of their actions in the past, present, and possible future influencing their teaching process. The interview questions were open-ended to get as many details from the teachers’ experiences as possible and to allow the participants to elaborate on their responses.

Lesson observations, on the other hand, aimed at exploring the enactment of the ESC as the participants acted upon policy adoption and adaptation dynamics within classroom life. Information gathered through lesson observation also served as an entry point to validate or contrast teachers’ expressed agency development from the interviews. This ultimately allowed us to analyze how the teachers’ trajectories of action were reflected in day-to-day decisions at the micro-level (the EFL classroom).

Finally, we used teachers’ narratives to assess a more in-depth depiction of their teaching decisions and agentic moves when enacting the ESC in their educational context. The narratives provided an account of the participants’ discourses and perceptions of their teaching practices as portrayed in their own words, retrospectively, and in detail. We sought to identify the interplay of the three dimensions of agency embedded in their experiences, as these reflect trajectories of action.

Context and Participants

Two state schools in Montería, Colombia, were selected based on their recognition for being part of bilingualism projects promoted by national and local educational authorities, including implementing the ESC. School 1 has been implementing EFL policies since 2008, which means the schoolteachers have had different professional development opportunities to enhance their knowledge in English language teaching. School 2 has been recognized due to its high scores in state exams that test students’ proficiency levels in various subjects.

Three high school female teachers were purposefully selected for this study: Dorcas, Yua, and Mirabel.1 Dorcas and Yua are teachers in School 1, while Mirabel teaches in School 2. Teachers’ selection was based on three primary criteria: (a) seniority (teachers with over eight years of experience); (b) role (in-service English teachers belonging to the language department at the selected schools); and (c) closeness to curriculum creation (teachers who did not participate in the writing, evaluation, or piloting of the ESC).

Data Analysis

To analyze the data, we followed a two-step analytical procedure. First, we adopted the teacher’s Chordal Triad of Agency Development model, as defined in Priestley et al. (2015). It served as a framework that guided part of the data collection process since the categories were considered for structuring the interview and subsequent data analysis. Accordingly, we situated the data within the three dimensions of teachers’ agency (iterational, practical-evaluative, and projective) in codes and themes derived from the semi-structured interviews, lesson observations, and narratives. Second, we used thematic analysis, as new categories from each teacher’s framework for action emerged from the data to analyze the report of the participants’ experiences and strengthen the use of the model for teacher agency. This involved following a deductive approach guided by the steps defined in Braun and Clarke (2006), namely: familiarization, coding, generating themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and finally, writing up.

Interviews were transcribed. One interview was conducted in English and two in Spanish, based on the participants’ preferences. The latter was translated from Spanish to English and analyzed using a color-coding technique, first using the chordal triad of agency and then following thematic analysis, as described above. The same procedure was applied to teachers’ narratives. Lesson observations were first recorded using a protocol for lesson observation we designed based on the lesson stages derived from the ESC. The protocol allowed the systematization of data by registering a synthetic description of lesson stages that included teachers’ and students’ doings. The instrument was validated using the member-checking technique (Birt et al., 2016) with the participants after data collection. Lesson observations were then coded following the same two-step analytic procedure described above.

Findings

Teachers recontextualized the ESC influenced by autonomous decisions derived from their teaching experience, students’ needs, and institutional context. This section presents three models that reflect the elements involved in teachers’ adaptations of the ESC. Each teacher’s framework for action is described and analyzed separately. First, we present a comprehensive visual representation that summarizes each teacher’s framework for action. Then, we describe each element in the framework, supported by instances found in the data. Additional general interpretations are made at the end of the section.

Mirabel’s Framework for Action

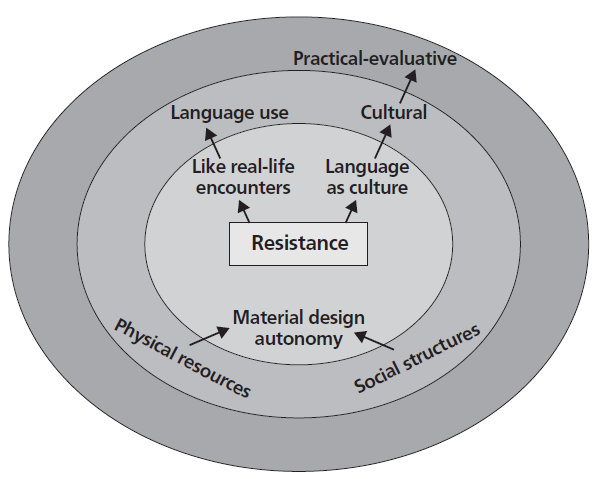

Mirabel’s adaptation of the ESC was permeated by critical views on policy documents, substantial autonomy over her work, and low alignment with the objectives of the ESC. We define it as the interplay of resistance, autonomy, and the evidence that teachers’ agency, in particular cases, can become a constraint for successful language policy adaptations.

Figure 1 represents the orientations Mirabel brought into her teaching. The outer circle represents how the teacher’s model is situated within the practical-evaluative dimension of teacher agency, as proposed by Priestley et al. (2015). The middle circle displays the categories already existing within the dimension and undertaken by the teacher. The inner circle represents the intersection of the elements pertinent to Mirabel’s framework for action, which permeate her recontextualization of the ESC.

Language as Culture. The ESC includes cultural knowledge by motivating teachers and learners to evaluate the main pitfalls or dilemmas around the country’s situation. Globalization, health issues, and environmental problems are some of the critical scenarios the curriculum presents. In this respect, Mirabel opposed the “Colombian-oriented” approach: “Every time I say, ‘OK, don’t talk about Colombia, do the research about Asia…Europe,’ so, I always try to force them to do something overseas.”

In this perspective, Mirabel pushed her students to be culturally aware of other ways of living beyond contextual information. These views motivated students to go overseas without ignoring the cultural elements involved in language learning and how these shape forms of life within varied countries and realities. The implications these adaptations have on policy enactment can be translated as high interest from the teacher to help their students based on their needs, lacks, and wants.

Material Design Adaptation and Autonomy. When referring to using textbooks for English language learning at her school, Mirabel stated: “We don’t use the books that the government sends…We don’t use them because our students are a little bit higher level.”

As noted, in her use of the word “we,” teachers decided as a team the type of textbooks that would suit their context, as opposed to the books the government designed and sent for use. Teachers reacting to the constraints of the inaccuracy of materials for students’ use resulted in acting out together to create instruments that would help them opt for a different book: “We had a bunch of books, so we were using the checklist, and then we got together and, so it came out [sic] to two books.”

We evidenced high usage of the book selected, including other teaching materials such as a webpage and a worksheet. Mirabel expanded on the stages involved in her lessons’ development: “First, I need to pinpoint the goals of what I will be teaching, then, I’d try to get some knowledge into [the students’] current state (diagnostic); I’d try to define the stages and materials.”

None of the steps directly states that Mirabel considers the themes addressed by the ESC when planning, claiming autonomy over material use, and lesson development. Her perceptions towards enacting the ESC portrayed a critical view on the type of practices occurring at her school, talking about the role of teachers when adapting the policy or stating her thoughts towards the work done. Hence, when moving towards choosing another book for EFL learning at her workplace, Mirabel disagreed with the option selected and finally went against the collective agreement. There was a shift from one type of agency (collaborative) to another (individual). From including herself within the group of teachers, to finally stating that she separated from her coworkers and chose something else, as evidenced in the following extract:

I was the only one who wasn’t really happy with [the book]…so [my coworkers] chose the other [book], and I don’t like it, I hadn’t worked with it. I only worked with it one year. and then when I worked with it, I was like, “no, I don’t think it is appropriate.”

The extract reflects how much a teacher’s thinking patterns influence what ultimately goes into the classroom. Despite what the policy stated, Mirabel chose her path to enact the EFL policy even against what her fellow teachers decided as a team. Although Mirabel built up a strong awareness of collaborative work, her agentic moves were characterized by individuality and deep-rooted beliefs opposed to other teachers’ views.

This experience, where teachers take the initiative to adapt EFL policies to their classrooms, lies beyond policymakers’ control. Thus, with or without the school administrators’ knowledge, the teachers lead a process that moves beyond the policy text and opens spaces for change within schools. Ultimately, the students are directly exposed to the teachers’ policy adaptations.

Motivating Language Use in Real Life. In terms of students’ language learning development and usage, Mirabel sought to help students go beyond the basic grammatical structures that were usually taught, involving students in the reality of the language as it influenced their lives. In this respect, she stated: “I’m always like, ‘use it in your real life, say something related to your own personal experience.’”

Mirabel motivated students to think about the use of a second language since she thought about language learning as something that transcended the classroom context: “I always try to look for that kind of activities and exercises and tasks that are like, from real life or that will help them, you know.”

How Mirabel approached language development in her school context was motivated by her desire to inspire students to use the language in situations from the real world. When contrasting her strategies against what is stated on the ESC, Mirabel aligned with the curriculum regarding using real-life issues to promote language use.

On the other hand, the ESC serves four dimensions in which health, environment, education, and democracy are widely explored to guide the students’ critical thinking on their country’s development situations. However, Mirabel’s curriculum implementation diverted from the dimensions presented, including different topics in her chosen materials. She claimed:

I think they are just taking things that are fashionable worldwide and then bringing them to Colombia with no research whatsoever, and it’s just that they say, “Oh, everybody else is doing it, so we have to use it here,” yeah, but they don’t really see that we need more background.

This also resulted from the perceptions she had about the curriculum, and that permeated the adaptation process of the ESC.

Dorcas’ Framework for Action

Dorcas’ work became a guide for other teachers to rely on, as she designed strategies beforehand, brought forth new ideas, and became the first to design and implement teaching materials that other teachers later used as a reference for their teaching practice. Her framework for action was shaped by a view of teaching permeated by collaboration with others. This perception of teaching aligns with a new view of agency that goes beyond analyzing individual duties involved in policy implementation and considers the analysis of collective work when teachers rethink and adapt policies. The following themes derive from the construction of Dorcas’s framework and promote evidence on how networks of teachers are relevant in EFL policy enactment.

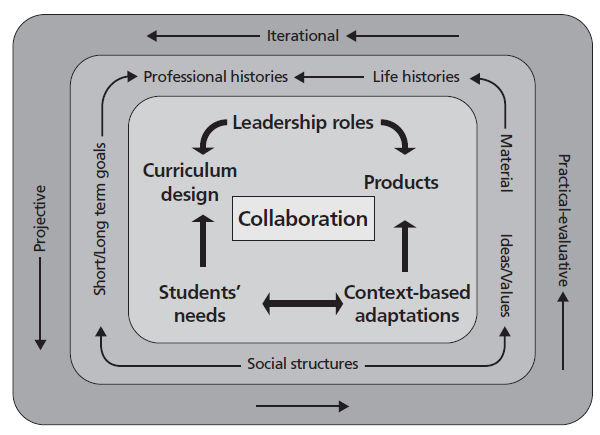

Dorcas’s framework for action (see Figure 2) describes the interrelation among her leadership roles; interest in participating in curriculum design, reform, and implementation; the conception of students’ needs as the core of her teaching; and promotion of the presentation of products in the school community.

Leadership Roles. Dorcas’s agency construction was mainly characterized by acting upon ideas and roles that made her a pioneer in several aspects of EFL policy enactment. When referring to her role among networks of teachers at her workplace, she stated: “I’m always going a little bit ahead because I’m more intense.”

This is supported by a second comment in which she stated that, during the pandemic, “I was the first that designed the English worksheets, and I gave all [the other teachers in the team] my guidelines; then, based on my format, everyone worked on their guidelines.”

Although Dorcas begins by describing her efforts, she includes them within the umbrella of teamwork. In the statement, she reflects upon the changes that the pandemic brought and the enactment of the policy that demanded public-school teachers create worksheets to help students advance their education remotely.

This leadership is linked to teaching experience derived from management roles in the past. She recognized that, while working at a private school, she gained the “basis for school organization”; therefore, the roles taken at her current workplace were influenced by that expertise. Connections between past decisions and present challenges reflect the role of professional histories and previous experiences in shaping teachers’ agency development. They reflect teaching flexibility as an exercise that is not always steady or limited to the present constraints.

Teachers move across past and future projections to define trajectories of action. Therefore, Dorcas’s views about school curriculum, teaching, and schoolwork influenced how she enacted the curriculum, not from an individual role but considering collaboration among other groups of teachers as well.

Curriculum Design. Dorcas’s framework for action brought forth an understanding of how teachers at her workplace designed, adapted, and used their teacher knowledge to create curricular guidelines before the ESC was introduced and adapted: “We had created before the education ministry released a suggested curriculum, we had come up with curricular English learning guidelines for the city.”

Derived from the necessity of having organized and clear guidelines when she arrived at the new public school, Dorcas and her colleagues worked together to help. This resulted in a series of documents that motivated English teaching from a different perspective. For example, she mentioned that she had designed a curriculum structure for the grades she taught, ensuring the scope of topics to instruct English at the school. She recognized: “I felt out of place . . . we need to have a route and know how we are going to teach what students must know in sixth, seventh, eighth…we have to sit down and create a syllabus.” Therefore, when the ESC was brought to their workplace, she commented: “We had already been working, super! Let’s integrate it to what we have.”

Teamwork among her colleagues also was enhanced by the necessity of going beyond teaching by the book. When referring to adaptations to the ESC, Dorcas stated: “I don’t like working with a book, so we left it beyond the book.” In her narrative, she continued: “At that time, we were thinking about functions of the language more than grammar, so when the ESC came, it was a perfect match for what we expected. We adapted it to our specific needs and context, and now we are working with the results.”

Whatever Dorcas’s vision for the school promoted changes in how the ESC was conceived and adapted, rethinking the role of teachers’ aspirations might provide valuable evidence on why they achieve more than is expected, even as the context is filled with constraints. Teachers often act upon interests and necessities unknown by policymakers and school administration, only tangible when their work’s high or low quality is visible.

Similarly, integrating the ESC into their local curriculum reflected how each teacher’s vision influenced how EFL policies were adopted. Dorcas commented how colleagues embraced their role as English teachers from the “bilingualism program,” reflecting the affection placed on how they worked since they were called to implement the EFL policy. In this respect, she commented: “Well, the truth is that in 2009 the school began with the bilingualism program; since then, we are always working on anything so that students learn.” Dorcas considered students’ needs the core of the EFL teaching and learning process.

Context-Based Adaptations. Dorcas’s lesson development evidenced a high usage of context-based knowledge. Her teaching moves were framed using questions to promote students’ participation. This dynamic is aligned with institutionalized policies within the school context, in which the learning model encourages questioning. Considering policy guidelines (the ESC and the school pedagogical model) at the micro-level denoted the influence of policy text on the classroom’s reality. However, as Dorcas’s narrative further describes, most of the adaptation process remains hidden. She stated that lesson development involved a complex process: “I think and think about possible activities: fun, academic, modern, challenging, interesting, related to Saber test.2 Then I plan, adapt, implement…I feedback myself and start all over again.” Hence, she reshaped further moves informed by the role of her teaching in given situations within the past and present.

Along the same lines, Dorcas’s work in her lesson evolved around language and was framed by vocabulary-oriented activities and collective-task development. These orientations were characterized by including topics addressed in the ESC and following the pre-, while, and post-task sequence, as suggested in the ESC. Similarly, the grammatical structures she used during the lesson aligned with the ESC, and she motivated group work and critical analysis of topics such as poverty, education, and climate change.

Products in the School Community. In Dorcas’s perspective, English teaching needs to transcend into the community. Therefore, teachers designed activities transcending the classroom, making learning products accessible to the community. For instance, she referred to a song festival in which students participated each year. Teachers motivate students to choose songs with a specific topic based on the four ESC curriculum areas. This exercise requires students to select and practice songs that talk about health, peace, democracy, or social justice. In this respect, she commented: “The song festival always has a core topic, so the student can focus on those four pillars that we were working on throughout the year.” Therefore, the objectives of the ESC were reoriented to students’ interests, promoting activities that transcended the classroom and fostering the development of skills to use English for a specific purpose, like singing and performing.

Although it is unclear whether this dynamic was permeated by past teaching experiences or orientations toward the future, Dorcas displayed a high level of consciousness of the impact of language learning on her students. When analyzing the song festival’s role in fostering students’ language acquisition process, we noted that more than an activity, it became an experience for students, who ultimately brought more than the usually taught skills into their performances.

Student’s Needs. Dorcas recognized that students are most influential in determining what is taught and reshaped. In this respect, she commented: “I can take the idea from the ESC guidelines . . . for example, let’s work on health, but I adapt depending on the population I have.”

Dorcas reconsiders what, when, and how to teach based on the modifications needed for students to learn the language. Despite the curriculum presenting a selected number of topics and objectives, the teaching points were determined by students’ strengths, weaknesses, or learning styles. In addition, the constraints within the context permeated her practice. When addressing the issue of large classes, for instance, she commented:

The challenge is to know that all of your students won’t be able to participate because there is not the time and there are too many students in a single classroom. You would spend the whole school term trying to do one thing, trying to listen all of them, then you see that the ones who dare are the ones who will outstand, and the shy ones will remain lagging because there is not the possibility.

Dorcas tackled students’ needs by proposing alternatives that help them develop language skills. She added, “You mediate as you go; you mediate according to the population you have.”

Yua’s Framework for Action

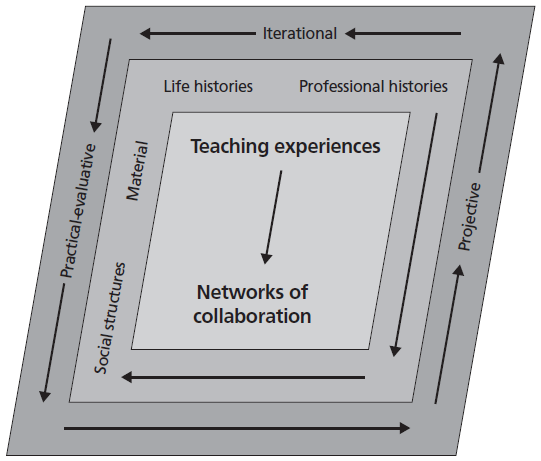

Strong relationships with other teachers and collaboration determined Yua’s approach to policy enactment. However, her speech was not as explicit as the other participants due mainly to time constraints during the interview; her past experiences influenced how she enacted the policy and coped with the changes from implementing the ESC. Hence, her model for policy adaptation was framed within three main aspects: teaching experience influence, acting out the policy, and collaboration (see Figure 3). The elements displayed in the model show the relationship among the iterational, practical-evaluative, and projective dimensions of agency. Her framework includes the role of Yua’s life and professional stories in constructing experiences that mostly permeated her practice.

Teaching Experience. Yua commented that her first teaching experience tested what she could handle as an educator: “It was a little traumatic at the beginning. I said, oh God, I’m not going to be able to. I felt frustrated when I started.” In this first teaching experience, most of her students had personal issues, and teaching demanded more than adapting objectives taken from the ESC. In this respect, she gained a perspective in which her actions depended on her knowledge of the English subject and were influenced by the degree of incidence the context had on learners. She said: “I had sixth graders that were over the standard age, they should be in 10th or 11th grade; students on drugs and all that kind of things…aggressive…then, it was a challenge.”

In terms of overcoming the experience, she stated what it meant for her: “One learns different types of strategies, let’s say, the methodology is not the same, you learn how to know the kids, you learn that you will not always find the same type of students.”

Yua drew upon her experiences to make well-informed decisions, as these experiences also enriched her capacity to act. As an experienced teacher who has enacted the ESC for various years, her perspectives on teaching are deeply influenced by her previous teaching background. This shapes how her lessons develop and how she acts toward students. This element aligned with her present decisions, correlating her previous background and possible trajectories of action growing when facing current constraints and dilemmas.

Influence of Contextual Factors. Yua’s approach illustrated how variations at her workplace triggered changes in the ESC: “Whenever I start to work with a class, I realize that the topic is maybe too advanced for students’ level, then, I have to readjust it.” Similarly, she stated that the curriculum documents were adopted, adapted, and adjusted depending on the population. She explained: “It suggests, it guides, but it is not totally compatible.” This resulted in high autonomy over her work, influenced by the thought that “education is evolving, times are changing, the students are changing.” Thus, Yua adapted the policy based on contextual factors such as the students’ level and the evolution of education.

Additionally, she highlighted that “in face-to-face learning, one of the aspects that [has an influence is] the mood of the students.” She commented that she made learning entertaining, avoiding students’ boredom during the lessons. Similarly, she pointed out how she acts as a teacher and the main elements she considers when teaching: “I am also a very sensitive teacher that cares a lot about my students’ problems. I try to take into account their weaknesses and strengths as well as their interests and learning styles when planning my classes.”

Collaboration. The analysis revealed that Yua built up a strong awareness of collaborative work. In this perspective, her agentic moves were characterized using pronouns referring to groups when talking about her work:

It’s what we have done this year; actually, this year we were already working and making some adjustments because sometimes we saw that the topics repeated too much, the topics we will teach, so we had to make various adaptations of this kind.

Autonomy over her work included consulting other colleagues on activities and instructional tasks to be carried out in the classroom. Framed by networks of collaboration among other teachers in her context, her framework developed across the three dimensions of agency with a high retrospection towards her teaching experience and life/professional histories. Similarly, social structures and material resources were prominent since her students’ moods influenced her adaptations to the ESC.

Likewise, Yua collaborated with other teachers to make informed decisions to foster students’ learning process. Based on what previous teachers accomplished with the students, she could gain a perspective on the future elements that could be worked on. In this regard, she commented:

The coworker that had [the students] the previous year always gives me feedback: they are like this, these students have these specific traits…then, well, that helps a lot in fostering the language learning process, right, the level, because we take into account what the teacher did, where he got to in order to continue the process. Until now, that has given us good results.

This sense of collaboration among coworkers fostered students’ scaffolding across different levels of learning. Based on Yua’s comments, teachers consider the results of other colleagues’ practices to address the specific needs of learners.

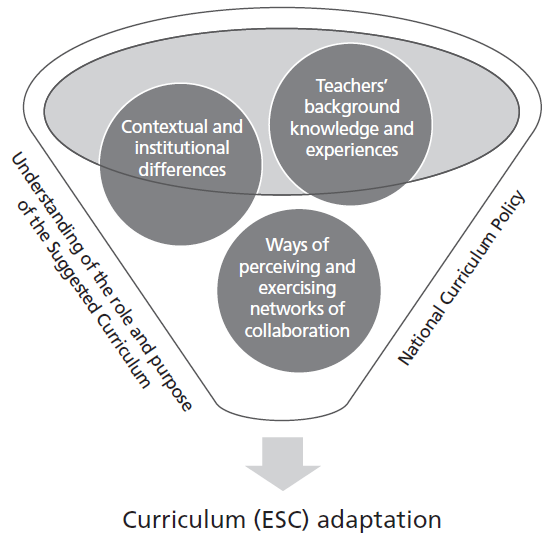

The Agency Vessel

Figure 4 visually summarizes the agency development aspects shared among the three participants. Likewise, it addresses the divergences in their trajectories of action, influenced by their iterational, practical-evaluative, and projective agency. Teachers’ unique ways of managing the implementation of the ESC varied across their practices since they introduced elements from their background knowledge and life experiences into the adaptations they made. In other words, teachers did not come to the adaptations empty-handed but were filled with the vital elements they gained from their worldviews and past experiences.

Figure 4 represents the teacher’s agency in the form of a vessel. The elements surrounding the vessel are those aspects that converge based on the data analysis: the national policy (the curricular guidelines), teachers’ understanding of the policy’s role, and the national ESC’s position in their practice. In this sense, the three teachers agreed on the role of the ESC, not as an imposition but as a guide permeated by the adaptations the schools and teachers made of it. In general, they considered the objectives, activities, and proposed aims of the ESC, but made changes informed by the context, ultimately influencing students and the school community. From this perspective, the elements surrounding teachers’ adaptations must be considered as the interrelation between introspective and retrospective elements that affect teachers’ lives and, ultimately, teaching.

In terms of divergence, three elements were crucial: the different ways teachers may conceive and exercise collaboration networks, contextual particularities, and teachers’ background knowledge and past experiences. Although teachers worked along networks that fostered collaboration, the reality of what they brought to the classroom was shaped by the transitions among iterational elements derived from their experiences, lives, and present situations. The study on teacher agency by Priestley et al. (2015) concluded that the type of school influences how teachers react to the constraints or demands when facing policy implementation. Teachers are shaped by the kind of teaching experiences they have, whether these are supported, encouraged, or ignored. Dorcas’s school, although not directly promoting how teachers could cope with the ESC policy, held a culture of recognition of the English language, supported by the high level of freedom teachers had to exercise their agency. The school emphasized the role of collaboration by grouping teachers based on the subject they taught—known as “nucleus”—which widely influenced their teamwork approaches. This was evident when Dorcas spoke from the team perspective instead of individual characterization. On the contrary, Mirabel repeatedly opposed the notion of teamwork, denoting discontent towards what her team did. Aligned with what was stated in Priestley et al. (2015), Mirabel held a “repertoire for maneuver,” as her experiences (even beyond teaching) influenced what went into the classroom as well.

In addition, subgroups of teachers inside schools provide evidence that collaboration promotes or hinders change. In the current study, both perspectives are reflected by the participants. Two teachers recognized collaboration as positively influential in fostering the ESC’s adaptations, while the other resisted change, opposing cooperation with other teachers and exerting autonomy over her work. These discrepancies in the role of collaboration reflect how different the positions taken by teachers within different schools are, increasing the necessity of analyzing the realities of schools from the perspectives of teachers and their experiences when adapting any new foreign language curriculum.

Conclusions

This paper has described three high school teachers’ approaches to curriculum policy adaptation. Since each teacher possessed unique ways of interpreting, adapting, and adopting the ESC, we gained a perspective of the different roles, actions, and thinking patterns that permeated what they ultimately brought into the classroom. We also explained how these adaptations converged and differed, summarizing the most prominent elements in what we called the agency vessel. In this study, we drew essential elements from teachers’ discourses, which can help to explain how several aspects of their context serve as enablers or constraints of their agency, resulting in the construction of their frameworks for action and working upon trajectories of adaptation permeated by their past, present, and future decisions. Additionally, we described the transitions between individual and collective teacher agency, evident during the ESC adaptation process.

Limitations in the data collection process included the length of the teachers’ discourse to further nurture the analysis of patterns across the data. For example, although the prompts encouraged detailed descriptions in the written narratives, recounting elements of their experience was relatively short. However, the data collected allowed us to obtain insights into each participant’s agency development. Analyzing how teachers cope with the changes derived from policy discourse enactment provides significant information that can inform how future EFL policies are created and promoted. Rarely are teachers consulted on adapting the policies, leaving aside the valuable knowledge they can provide to shed light on future EFL reforms and aspects that might nurture their teaching practice.

Hence, it becomes fundamental to investigate the influence, design, and assembly of the teachers’ practices at the micro-level. Further research could analyze the nature of these adaptations in rural contexts or schools that lack networks that foster collaboration or where teachers struggle to reshape policy discourse. This suggestion stems from the necessity of exploring the impact of reforms in peripheral contexts in a country where policymaking is often centralized in the big cities.

In terms of teachers’ agency theory, this paper contributes to its ongoing development by undertaking an existing model and using it to analyze agency development in three teachers. The conclusions gathered from each participant can provide a robust understanding of teacher agency development and its role in EFL practices or adopting new curricula in Colombia. Looking further into how teachers enact, adapt, or resist policy can also inform future curriculum developments in Latin America and across global contexts at a time of increasing interest in teachers’ agency development.