Introduction

As of the enactment of the Political Constitution in 1991, Colombia became a democratic and social state where ethnolinguistic, racial, and religious differences were acknowledged, valued, and preserved within a multicultural frame. However, educational, socioeconomic, and political equality have been elusive, especially for racialized, minoritized populations, such as Indigenous, African-Colombian, and Gipsy Roma peoples (Viáfara López, 2017). The “structural subordination” (Grande, 2004) of racialized populations in the Americas and the Colombian context—our locus of enunciation—is the aftermath of the intricate dynamics of colonization, which “persistently impose particular conceptions of what it means to be human and defines what counts as cultural difference” (Gaztambide-Fernández, 2012, p. 42). In Latin America and the Caribbean, the White-Mestizo1 population has imposed its republican, Anglo-Eurocentric values over the rest of the population, enforcing technologies of sexual, racial, and social disciplining to manufacture “subject positions,” limiting human encounters to the aspirations of this hegemonic ethnoclass (Foucault et al., 1988).

Adopting critical intercultural and decolonial perspectives can facilitate more humane encounters with difference. These encounters help us overcome the “colonial horizon” (Rivera Cusicanqui, 2012) marked by racism, heteropatriarchalism (sociocultural and political systems where heterosexuality and patriarchy are deemed natural and the norm), heteronormativity (social construction that normalizes heterosexuality as the default, only legitimate sexual orientation), phallogocentricity (logic that configures reality around male perspectives and categories) (Cixous & Clément, 1975/1986), and the instrumental rationalities (the assumption that any means is valid to achieve one’s ends) of conventional schooling.

Higher education (HE) in developing countries suffers from the geocultural subalternization of knowledge and the imposition of policies and discourses that favor particular ways of producing knowledge and administering education. University stakeholders, especially teachers, are called to adopt critical views about how universities operate at the administrative and educational levels. This challenge raises the question of whether stakeholders, especially teachers, can use counter-hegemonic practices to reverse the colonial resonances inherent in HE. One first step is to recognize the populations historically suffering from a lack of access, recognition, and participation in HE, including African descendants, Indigenous communities, peasants, and LGBTQ community members. A second step is to work with these communities and establish an intercultural dialogue to identify needs and paths of action to improve their conditions. In this article, we draw on the experience of conducting research with Indigenous university students, a historically (Waller et al., 2002) and structurally (Usma et al., 2018) marginalized population in HE. We analyze their barriers to access and complete their studies and propose some actions to make HE more diverse and accessible to this population.

In this reflective paper, we adopt social semiotics, critical interculturality, and a decolonial stance to discuss how stakeholders and teachers could foster intercultural encounters and understandings to facilitate Indigenous student engagement in sustainable intercultural dialogues. Next, we provide a brief theoretical overview and discuss some barriers. Indigenous students face in HE. Finally, we propose strategies to ameliorate Indigenous students’ experiences from our perspective as English language educators.

Conceptual Framework

Social Semiotics

Social semiotics examines the structure, processes, and effects of the design, reception, and dissemination of meanings enacted by agents of communication (Kress, 2010). At the heart of social semiotics is meaning-making, emerging from intersecting individual, social, historical, material, ideological, and cultural dimensions. Culture is central to social semiotics. It constitutes an open and dynamic repertoire of semiotic resources (material and symbolic beliefs, discourses, ideologies), constructed through processes of regularization, ritualization, and conventionalization of social practices, which become sedimented through time and acquired during processes of socialization (Álvarez Valencia, 2021). Semiotic resources refer to any artifact (e.g., sculptures, books), activity, event, or behavior (e.g., buying, flirting) and way of thinking (ideas, beliefs) that we use, deploy, or enact in designing meanings. Language is another semiotic resource central to communities because it is used to construct, disseminate, and reshape semiotic resources needed for community adherence and preservation.

Individuals develop a repertoire of cultural semiotic resources deployed in any social situation throughout their lifespan. This repertoire of resources is built within the multiple communities and social and cultural groups wherein individuals participate, which are determined by geographic, linguistic, national, racial, ethnic, sexual, gender, religious, institutional, political, physical, and socioeconomic dimensions. By participating in diverse social and cultural groups, individuals develop affiliations and appropriate semiotic resources proper of these groups (e.g., male behaviors and visions of masculinity), ultimately shaping their identity. In turn, individuals’ semiotic resources are intersectional because practices, values, aspirations, and discourses of multiple cultural groups take a particular shape and are enacted by an individual. Therefore, every interaction between individuals involves a negotiation of their repertoires of cultural semiotic resources and is, by nature, an intercultural encounter (Álvarez Valencia, 2021).

Interculturality and the Decolonial Perspective

Interculturality refers to a perspective on the process, conditions, and effects of the encounter of members of various cultural groups. In social semiotics, this perspective on interculturality articulates with a decolonial orientation representing a political project for critical, liberatory, and emancipatory action (Walsh, 2009). Interculturality constitutes an ideological principle for a political process and project “in continuous insurgence, movement, and construction, a conscious action, radical activity, and praxis-based tool of affirmation, correlation, and transformation” (Walsh, 2018, p. 59). The decolonial perspective embraced here is inspired primarily by the Indigenous social movements of Abya-Yala (or the American continent); however, we adopt a dialogic approach where voices from the Global South and Global North engage and interact critically (Guilherme & Souza, 2019).

The decolonial perspective aims to transform, reconceptualize, and refound semiotic resources (e.g., ideologies, practices, products) and the meanings that shape hegemonic structures, institutions, and forms of interaction that perpetuate the colonial matrix of power, knowledge, being, and mother nature. A decolonial view prompts us to delegitimize the meanings that naturalize racial, political, gender, and social hierarchies implanted through the coloniality of power (Quijano, 1992) and to reject imaginaries that position the colonized as cognitively, emotionally, and spiritually inferior (coloniality of being; Maldonado-Torres, 2007). Likewise, decoloniality invites us to re-envision our broken relationship with nature, characterized by our exploitative, consumerist, and accumulative logic (coloniality of mother nature; Walsh, 2009).

At the educational and pedagogical level, a decolonial orientation articulates with critical (Freire, 1968/1970; Giroux, 2009), asset-based, and multimodal pedagogies (Álvarez Valencia, 2021; Stein, 2007), for they share a critical view of education and a commitment to pluriversal views. Such articulation facilitates the encounter of diverse cultural semiotic resources, including frameworks of interpretation, cultural practices, ways of learning and knowing, acting, thinking, being, and living, and “contribute to the creation of new comprehensions, coexistences, solidarities, and collaborations” (Walsh, 2018, p. 59). While critical pedagogies highlight the need to challenge broader social structures of power by examining “the role that schools play as agents of social and cultural reproduction” (Giroux, 2009, p. 47), asset pedagogies—such as culturally sustaining pedagogies (Alim & Paris, 2017)—conceive of schooling as a site for sustaining the cultural ways of being of minoritized cultural groups and provide options to respond “to the many ways that schools continue to function as part of the colonial project” (Alim & Paris, 2017, p. 2). Multimodal pedagogies focus on re-sourcing (rearticulating, recovering, and legitimizing) students’ cultural semiotic resources (e.g., linguistic varieties, gender identities, cultural practices) that have been disenfranchised or silenced by hegemonic forces and semiotic regimes operating in educational institutions (Álvarez Valencia, 2021; Stein, 2004). In short, these pedagogical perspectives, combined with principles of a decolonial perspective, strive for recognition, social justice, openness, and reflection through critical intercultural dialogue.

Critical Intercultural Dialogue

We understand critical intercultural dialogue as a reflexive, subjective positioning where interlocutors from diverse cultural groups engage in solidary interactions with attitudes of openness toward recognizing the self and the other’s cultural semiotic resources. This reflexive process is critical because it intends individuals to examine the gaps in cultural practices, experience, and history and “engage each other in a mutually educative and critical manner” (James, 1990, p. 589). By critical, we understand the capacity of interlocutors to assess their cultural semiotic resources, identify the social, political, historical, and economic forces that inform their assessment, and, finally, take a position that enables full or partial agreement regarding meanings or perspectives being negotiated. For critical intercultural dialogue to happen, interlocutors must recognize the equal or unequal conditions under which this dialogue is conducted and should strive to generate fair conditions that all parties involved can accept and revise as the participants and circumstances change (James, 1990).

We present some examples of how these pedagogical perspectives contribute to the decolonial intercultural project below, although a discussion of the situation of Indigenous students in HE is in order first.

Indigenous Students’ Barriers to Access and Complete Higher Education

Previous studies show that Indigenous students face similar challenges in accessing and completing their university degrees despite the geographic distance (Álvarez Valencia & Wagner, 2021). A case in point is Colombia, an ethnolinguistic and culturally diverse country with over 102 Indigenous groups that speak 65 Amerindian languages distributed across 788 Indigenous reservations (Agencia Nacional de Tierras, n.d.; see Figure 1). Besides Spanish, there are “two Creole languages, two varieties of Romani, and [the] Colombian sign language, which also has two varieties” (Usma et al., 2018, p. 233). Even though at the national level, the percentages of Black and Indigenous populations are considerably lower (Black, 9.34%; Indigenous, 4.4%) compared to White-Mestizo (86.25%), cultural métissage is high (DANE, 2019).

Source: Adapted from Portal de Datos Abiertos de la ANT, by Agencia Nacional de Tierras, n.d. (https://bit.ly/3Uvxy9A). CC BY 4.0

Figure 1 Indigenous Reservations in Colombia

The state has established education policies for Indigenous communities. Since the 1970s, it has encouraged creating and implementing “ethnic schools” with either an Indigenous or African-Colombian/Black-oriented curriculum (see Decree 1142, 1978). The policy intends to support education in the Amerindian or Creole (for Blacks) languages spoken in the territories to safeguard, maintain, and promote ethnolinguistic and cultural diversity. Regarding HE, even though state-funded universities assign admission quotas for marginalized, Indigenous, African-descendant populations, and for victims of violence, among others, these policies fall short when addressing the financial, cultural, academic, and psychological factors that these populations endure to succeed in HE (Álvarez Valencia & Miranda, 2022; Álvarez Valencia & Wagner, 2021; Usma et al., 2018).

Spanish is the official language in Colombia, and Amerindian languages are co-official in Indigenous territories, but some of these languages have become extinct despite preservation efforts (e.g., Pasto, Guajiba, and Pijao; Pineda Camacho, 2000).

English is also part of the equation since it is included in the national entry test for HE admission. Since 2004, language policies have set proficiency standards for high school and university students following the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Miranda & Valencia Giraldo, 2019). English constitutes a barrier to accessing HE, especially for Indigenous students who have received indigenous education in their reservations and for whom Spanish is already their second/foreign language.

Below, we present some barriers that hinder Indigenous students’ access, permanence, and completion of HE and impinge on the possibilities of engaging in intercultural dialogue between them and the campus community.

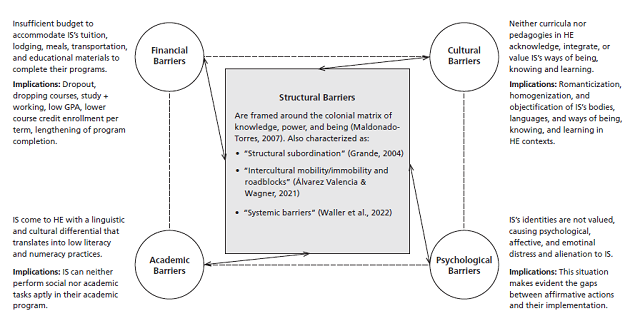

Structural Barriers

The worldview arriving from Europe in 1492 started the colonial matrix of knowledge, power, and being (Maldonado-Torres, 2007) that continues to mediate White-Mestizo and Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples’ socioeconomic, cultural, and political relationships in the Americas. The effects of the colonial matrix are particularly notorious in education. A review of the literature in the US (Waller et al., 2002), Canada (Ottman, 2017), Mexico (Chávez Arellano, 2008), Brazil (David et al., 2013), Colombia (Álvarez Valencia et al., 2021; Usma et al., 2018), and Chile (Merino, 2012) “indicates that even though enrolment of IS [Indigenous students] in postsecondary education has increased, they remain underrepresented at levels commensurate to the population and suffer from higher attrition rates and the lowest graduation statistics compared to other populations” (Álvarez Valencia & Wagner, 2021, p. 7).

Different authors have characterized Indigenous students’ journeys in HE in terms of “structural subordination” (Grande, 2004), “intercultural mobility/immobility and roadblocks” (Álvarez Valencia & Wagner, 2021), or “systemic barriers” (Waller et al., 2002). All coincide with the alienation, underrepresentation, and overall disenfranchisement of Indigenous students’ cosmogonies, identities, languages, and learning styles which have lower symbolic exchange value when circulated in the “property system of Western knowledge” (Ahmed, 2000, p. 148).

Financial Barriers

Even though in Latin American countries (Mato, 2018), Canada (Ottman, 2017), and some U.S. states (e.g., Arizona; see Waller et al., 2002), affirmative action legislation aims at providing financial support to Indigenous students, budgets do not suffice to cover their tuition, accommodation, transportation, meals, and educational materials to complete their programs. According to Restoule et al. (2013), Indigenous students receive “inadequate financial resources” for their transition/relocation from reservations to universities in urban centers. In some cases (such as Mexico), Indigenous students’ families invest all capital and land to fund their daughter’s/son’s HE (Merino, 2012) or engage in onerous student loans, turning a financial difficulty into a psycho-affective and emotional one. In Colombia, financial constraints among Indigenous students lead to off-campus employment, negatively impacting their academic performance by lowering their GPA, dropping classes, and prolonging program completion (Álvarez Valencia & Miranda, 2022; Álvarez Valencia et al., 2021).

Cultural Barriers

Indigenous students experience cultural discontinuities between their onto-epistemological constructions and the White-Mestizo culture as they “enter university and face the systemic and structural colonial resonances latent in the campus climate and stakeholders’ minds as well as the bureaucratic organization of universities that perpetuate covert discrimination, invisibilization, acculturation, and marginalization” (Álvarez Valencia & Wagner, 2021, pp. 11-12). Such discontinuities are marked by the “ethnocentric, conservative, and inflexible” (David et al., 2013, p. 118) curricula that neither include Indigenous languages, ways of knowing, being, and learning in teacher education programs or other disciplines nor question the inherent racism/colonialism in the academic/scientific disciplines.

Pedagogically, the lack of cultural awareness of Indigenous students’ differences implies romanticizing, homogenizing, and objectifying them by approaching them as “human museums” (Tróchez Tunubalá, 2017). Tróchez Tunubalá (2017) contests the view that portrays Indigenous communities as frozen in the deep past, incapable of changing and adapting to the demands of modernity. In most cases, teachers either neglect or disregard Indigenous students’ cultural and sociohistorical contexts while promoting “academicist” (the only valid and legitimate knowledge is the academic one), “transmissionist” (limiting learning to Western unidirectional logics where meaning is imposed rather than negotiated); and “assimilationist multicultural education approaches that sustain the historical legacy of exclusion of IS in higher education” (Waller et al., 2002).

Psychological Barriers

Indigenous students’ identities and cultural semiotic resources have historically been excluded in the Americas, “portrayed as negative, and even ridiculed” (Usma et al., 2018, p. 240). The cultural and linguistic discord caused by the new dynamics of city and campus life distresses Indigenous students, affecting their confidence and motivation and increasing feelings of inferiority and academic inadequacy (Álvarez Valencia et al., 2021), uprootedness (Waller et al., 2002), alienation, and social isolation (Ottman, 2017). These situations evidence the gap between affirmative actions and their implementation. By promoting this discrepancy, governments treat Indigenous students “more humanely” though not “fully humanely,” reinstituting “the very coloniality that yielded present conditions” (Gaztambide-Fernández, 2012, p. 45).

Academic Barriers

Both curricular and pedagogical segregation in universities originate in their inability to understand Indigenous students’ diverse literacy and numeracy practices. From Canada to Chile, research reports Indigenous students’ low language proficiency in the dominant language, including English (Ottman, 2017; Restoule et al., 2013), Spanish (Álvarez Valencia et al., 2021; Chávez Arellano, 2008; Usma et al., 2018), and Brazilian Portuguese (David et al., 2013). Research shows that Indigenous students struggle to understand and write academic texts, manage time in Western terms (Ottman, 2017), and participate in academic discussions with peers or instructors (Álvarez Valencia et al., 2021).

Indigenous students encounter greater challenges in learning English compared to Spanish. For example, Álvarez Valencia et al. (2021) report that Indigenous students from the Misak community in Colombia consider Spanish a foreign language. Thus, the requirement of English as a second/foreign language in HE disregards their sociolinguistic and language acquisition paths. For them, English becomes a barrier to completing their degrees because the proficiency level demanded in the courses ignores that their access to English classes, materials, and exposure to the language was limited during high school.

Indigenous students’ low English proficiency offshoots feelings of frustration and demotivation that lead to the abandonment of their English classes, which, along with the other barriers discussed above, translates into high attrition rates. Their GPA is affected by courses like English, where they feel disadvantaged compared to their Mestizo peers. Álvarez Valencia et al. found that Indigenous students’ GPAs in their university in 2010-2020 were 3.4 out of 5.0.

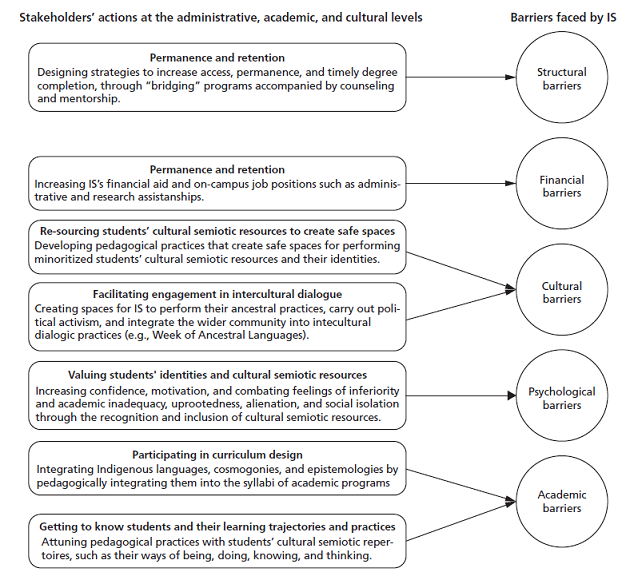

Figure 2 summarizes the barriers to genuine intercultural dialogue between members of Indigenous communities and university stakeholders. Below, we discuss how to promote, strengthen, and facilitate meaningful intercultural encounters between Indigenous students and the university community.

Initial Ideas on How to Construct and Develop Intercultural Dialogue

We focus on two main areas that will contribute to ameliorating Indigenous students’ access to HE: their permanence and the full enjoyment of the university experience. We propose that this can be achieved based on critical intercultural dialogue where the university community and Indigenous students exchange, negotiate, and contest cultural semiotic resources that perpetuate inequity. We describe two processes that will facilitate permanence and sustainable critical intercultural dialogue, highlighting our experience as English language teacher educators and providing examples from our classes; however, many of these ideas apply to other curriculum areas.

Facilitating Permanence

Permanence and Retention

To facilitate the permanence and retention of Indigenous students, the university community needs to draw unequivocally on an intercultural orientation. It must recognize the historical debt owed to Indigenous peoples in terms of providing equal opportunities and access to education, but more importantly, improving conditions for their success. This recognition cannot be reduced to admission quotas or financial aid; it requires recognizing the diversity of Indigenous students’ practices and linguistic, symbolic, and material-semiotic resources. This process involves disrupting the dynamics of a monocultural and monolingual campus and accepting and including Indigenous cosmogonies, spiritualities, and ways of teaching and learning.

One point of departure is addressing the economic, academic, psycho-affective, and cultural barriers that hinder Indigenous students’ academic performance and timely degree completion. Although they pay lower tuition fees, their primary challenge concerns affording life in the city. One way to guarantee a source of income is by increasing financial aid and on-campus job positions such as administrative and research assistantships.

Upon beginning their university studies, most Indigenous students report being academically behind their peers who had K-12 education in urban centers. They reported little instruction regarding English, while access to learning resources was limited (Álvarez Valencia et al., 2021). One way academic programs can facilitate student adaptation and academic leveling is by offering “bridging” programs (Usma et al., 2018) in different literacy practices. In several universities, tutoring centers have successfully supported students from multiple disciplines, including special tutoring for minoritized/racialized communities. Such initiatives must be accompanied by counseling and mentorship to identify students’ needs and follow up on their performance and progress throughout their university experience.

Counseling should focus not only on students’ academic needs but also on students’ psycho-affective dimensions. Indigenous students’ disorientation after leaving their territories and families and the feelings of marginalization in a foreign cultural context are also other causes of low performance and low-degree completion (Waller et al., 2002).

Participating in Curriculum Design

Another area that will enhance retention and intercultural dialogue is more involvement in curriculum planning and, at the pedagogical level, consideration of Indigenous students’ ways of learning. At Universidad del Valle, for instance, the Indigenous Council (Cabildo Indígena Universitario, CIU) has negotiated with the administration offering one Indigenous language (Nasa Yuwe) and two content-based courses about Indigenous cosmogonies and epistemologies. Including Indigenous courses is a step toward recognizing Indigenous communities, but more is needed for meaningful intercultural dialogue. Indigenous languages, cosmogonies, and epistemologies should be incorporated into academic programs, not limited to specific courses. In doing so, the possibilities of engaging in intercultural dialogue would expand since the semiotic resources proper of Western disciplines could be discussed in terms of Indigenous perspectives and vice versa.

One example is how we conceive of languages in contrast to Indigenous students’ views. In the Western tradition, second language acquisition has been dominated by a verbocentric, monolithic, and cognitive-oriented view where language is at the center of meaning-making and is situated in the mind of its “users” (Firth & Wagner, 2007). By contrast, the Misak community, an Indigenous pueblo in southwestern Colombia, conceptualizes language in three ways: Namtrik, which refers to the way people usually understand language as a formal system; Namuy wam, which denotes the voices of the territory manifested, for instance, through the chirps of the birds and the “voice of the wind”; and Kampa wam, which refers to the voices of their elder spirits found, for example, in figures of stones (Manuel Ussa, an Indigenous university student. Personal communication, September 25, 2019). Given the complexity of this perspective, language teachers must consider how their language assumptions can dialogue with those of their students in class.

Including Indigenous knowledge in the curriculum is a decolonial practice that allows non-Indigenous students to recognize alternative ways of thinking, doing, and staying in the world. Including other perspectives in a class and the syllabus can take different shapes. Depending on the course, some topics can contribute to expanding the course themes by looking at them from an Indigenous perspective. Guest speakers from Indigenous communities and Indigenous students enrolled in the classes can facilitate and strengthen this intercultural dialogue. One illustration of this approach is a pedagogy course that we have taught in the context of a foreign language teacher education program. In our course, several Western perspectives on education and pedagogy are studied; however, the course includes a unit on Indigenous and African descendants’ pedagogies. The unit closes with a colloquium where teachers of ethnic-racial communities discuss their philosophies and pedagogical practices with our students.

Getting to Know Students and Their Learning Paths and Practices

Consideration of Indigenous students’ learning practices is necessary for intercultural dialogue. One Indigenous student commented that he was reprimanded for not taking notes in one of his classes because he sat and knitted instead. Indigenous communities value oral tradition more than writing to harness concepts and preserve knowledge (Rocha-Buelvas & Ruíz-Lurduy, 2018; Tumiñá, 2019). For Indigenous students, there is a connection between listening and knitting because learning is an act of knitting the “word.” This anecdote emphasizes the need to rethink our pedagogies in diverse classrooms. Exploring our students’ cultural semiotic repertoires, such as their learning habits, classroom behaviors, and backgrounds, could offer insight into how to shape our pedagogical practice.

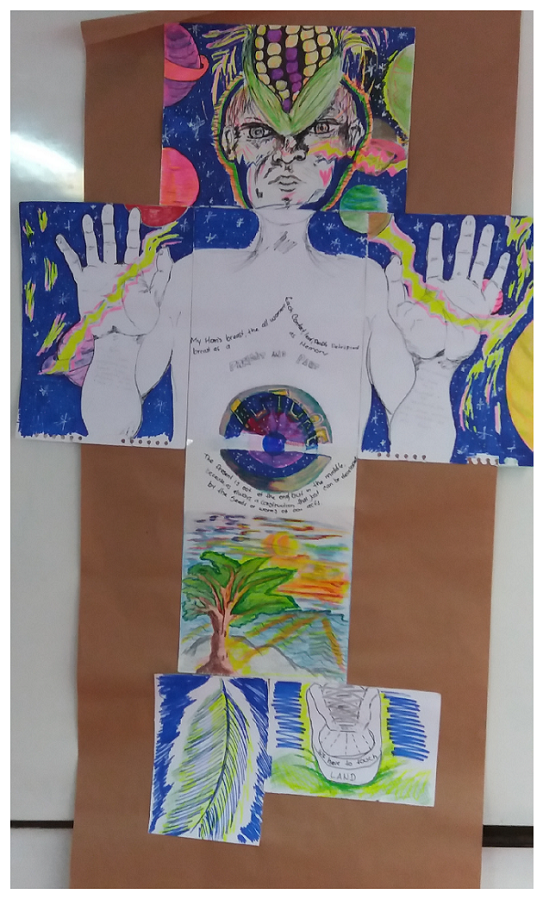

Several instruments could be used to engage in dialogue with our students and learn more about them. Teachers can use informal chats, surveys, and class activities and draw on classroom observations to inquire about students’ learning styles, practices, and cultural identifications. One strategy we have used in our Pedagogy course is asking students to introduce themselves through an identity text (Cummins & Early, 2011). Students have produced multimodal texts such as PowerPoints, video games, crosswords, posters, and even poetry that have become a window to their personal meanings and repertoire of cultural semiotic resources, including ethnic affiliation, affinity groups, gender identifications, and worldviews. The identity text in Figure 3 was produced by an Indigenous student of the Nasa community in 2016. Had we asked him to write who he was, we would not have gotten this rich, culturally embedded, semiotic, and symbolic resource.

In this identity text, the student explains who he is in relationship to his ancestral culture and the land. He questions the linearity of time and its split into past, present, and future, proposing a non-linear, mutually shaping conceptualization that conflates time and identity. He also acknowledges how land coproduces his identity and his sexed body. Pablo (a pseudonym) explains:

I don’t think I have an answer to the question, “who am I.” I think I’m under construction. I prefer to say who I am being. . . . Why the corn [as part of the head]? Because as you know, the corn is ancestral...is the ancestral fruit of our aboriginal people. That is my past, so I wanted to start by that . . . my head is an universe . . . As my universe could be the future, could be the past because when I go to the future, when I think in the future, I discover more about my past, my ancestral culture, my language. That’s why I say my future is in the past also. . . . The left hand is the symbol of resistance and is the force that prepares the right hand. The right hand for me is very important because it’s the hand . . . that creates many ideas. . . . This part [his sex] is like a seed, like a tree that shelters life. . . . Those are my feet. The left foot is a trapiche (mill). Because for me this is like, like we have to be in touch with the land to know what is our society, what our reality is. . . . But the right foot is different because even if you are a realistic person, you have to dream. For that reason, it’s like a leaf, and it represents the opposite of heavy (the left foot). [sic]

Re-Sourcing Students’ Cultural Semiotic Resources to Create Safe Spaces

Our pedagogical approach to language teaching is informed by multimodal pedagogies, critical pedagogy, and culturally sustaining pedagogies. We highlight the centrality of cultural semiotic resources as frameworks of interpretation that engage in dialogue and negotiation of meaning in the encounter between people and their repertoires of semiotic resources. As such, we look at the theories and contents of our class as cultural semiotic resources that are incomplete and contestable and which, therefore, need to be chronotopically, socially, and culturally situated and examined with critical lenses. We make the argument that one step in decolonizing English language classrooms is by questioning the status of language as the central meaning carrier and, instead, we give relevance to other modes of communication (e.g., image, sound, non-verbal elements; Álvarez Valencia, 2021; Stein, 2007). Expanding students’ representational resources, including their native languages, registers, styles, and social dialects, and welcoming their multimodal, multisensory, and embodied meaning-making practices in the form of arts, music, and visuals make the classroom a more just and equitable space (Stein, 2004, 2007). Thus, the language classroom not only welcomes students’ linguistic, cultural, and symbolic resources but also enables transemiotizing and translingual practices, implying a movement across semiotic resources that encompass not only the linguistic modality but also multimodal (e.g., gesture, space, gaze, image, color, typography, sound, music) resources (Álvarez Valencia, 2022).

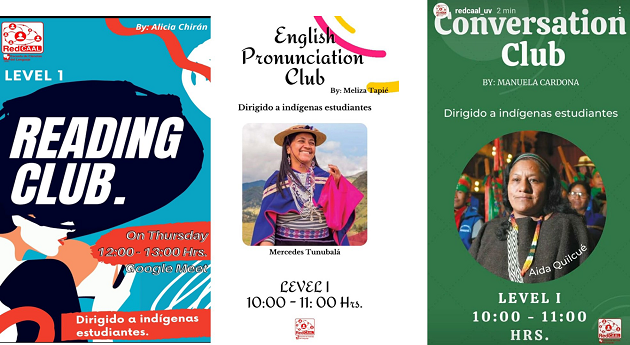

Teachers need to develop pedagogical practices that create safe spaces for the performance of minoritized students’ cultural semiotic resources and their identities. For example, in our teacher education program, as part of the teaching practice, three of our students (one mestizo and two Indigenous) designed language skills clubs targeted to Indigenous students of the university (see Figure 4). This initiative intends to strengthen students’ confidence, given the frustration they experience in their classes. These clubs also bring Indigenous students’ meaning-making practices and identities into the English language classroom through situated topics more attuned to their lives.

We have also implemented other strategies to make language classrooms safe spaces for the performance of students’ diverse identities. One strategy common to our pedagogical perspectives is re-sourcing resources because semiotic resources have uneven exchange values (Stein, 2004). The colonial matrix operating in Western education systems assigns a lower exchange value to Indigenous communities’ cultural practices and languages. The same applies to other categories, such as gender, where heterosexuality receives a higher exchange value than homosexuality. Re-sourcing semiotic resources intends to balance the exchange value of students’ cultural resources by making them visible, integrating them in the curriculum, and drawing on appropriate pedagogical strategies that invite students to participate and strengthen their identity.

One example of this initiative was evidenced in one of our classes of Pedagogy mentioned above. At the beginning of the semester, two students who phenotypically appeared to be of Indigenous origin did not identify themselves as such when showcasing their identity texts. However, at the end of the semester, they designed multimodal projects highlighting their Indigenous identities (one documentary about Indigenous women on campus and a sketch of the 21st-century classroom for Indigenous students). When asked why they had not initially made any reference to their Indigenous identity, Juana (pseudonym) explained:

Yes, I recognize myself as an Indigenous woman…However, I am not that active and that is embarrassing because I don’t know much about my culture. . . . The topics seen in class made me think and that is why I say that I recognize myself as an Indigenous person and if I did not name it much in class it was because, as I mentioned before, I am not so active with the activities, the cosmovision, etc. of the Indigenous council. So, I felt ashamed of my ignorance...When we touched on the topic of multimodal pedagogies, and also the topic of colonization, it was like it inspired me to know a little more about myself. (Personal communication, January 19, 2021).

The examples presented in this section demonstrate that English language and content courses can be venues for recognizing and resourcing students’ cultural semiotic resources. Classrooms can become collective territories that sustain and enrich students’ cultural practices and identity affiliations so that the “outcome of learning is experienced as additive rather than subtractive” (Alim & Paris, 2017, p. 1). In the case of the pedagogy courses, the intercultural and dialogic approach adopted by the teachers inspired the students to embrace their Indigenous identity and embody it with pride. The class supported students’ self-recognition and identity affirmation, which evokes Freire’s (2005) understanding of what critical pedagogy should afford in educational spaces: “Only as learners recognize themselves democratically and see that their right to say ‘I be’ is respected will they become able to learn the dominant grammatical reasons why they should say ‘I am’” (p. 89).

Facilitating Engagement in Intercultural Dialogue

At Universidad del Valle, Indigenous students have claimed spaces to express their identities. Álvarez Valencia and Wagner (2021) describe several of these achievements, including a temporary student residence for new Indigenous students, a chagra or space for Indigenous students to grow medicinal plants and other crops, a place called “Tulpa del Lago” where the community carries out cultural or political events and an office for the Indigenous council. All Indigenous pueblos of the university integrate the council. Members of the council are elected every year, and just as they would do it in their territories, the ceremony of inauguration is replicated on campus. Besides this event, the Indigenous council organizes other cultural and political events to share their cosmogonies, political struggles, rituals, and languages with the academic community. By bringing the cultural practices of their territories, languages, and overall cultural semiotic resources, Indigenous students reterritorialize the campus in what could be considered not only an invitation to engage in intercultural dialogue but also a counterhegemonic reconfiguration of the university, which they see as a colonial space (Álvarez Valencia & Wagner, 2021).

Despite the inclusion of the three courses in the university academic offer and of spaces for Indigenous students to carry out their events, for them, these benefits do not necessarily mean gestures for intercultural dialogue. On many occasions, they referred to these as achievements that were the product of their political struggle rather than initiatives of the university administration (Álvarez Valencia & Miranda, 2022). The university needs to create spaces for Indigenous students to perform their rituals and for other academic community members to participate and engage dialogically with the richness of Indigenous communities’ cultural semiotic resources. Facilitating intercultural dialogue does not only depend on the university community, but it is also a challenge that both parties have to negotiate regarding what it will be about and how it can take place under conditions that are fair to both (James, 1990). Intercultural dialogue requires, as suggested by Usma et al. (2018). This critical intercultural purview considers all dimensions (social, cultural, political, economic, historical) that intertwine in intercultural exchange and that underlie beliefs, stereotypes, and prejudice against others.

Language teachers can promote intercultural dialogue with other communities on campus. One good example of this is an initiative of our university’s Center of Languages and Cultures that, in partnership with the CIU, the Cultural Unit of the university’s library, and our research group, organized the Week of Ancestral Languages. During this week, teachers of English for academic and specific purposes courses offered to all the undergraduate programs in the university took their students to various events. Some of these events included “Círculos de Palabra” (an ancestral activity where people gathered around a circle to listen to each other and discuss specific topics), knitting workshops, music, dance demonstrations, and the design of comics about Indigenous narratives (see Figure 5).

Note. From left to right, students at a weaving workshop; music and dance demonstration; and fanzine produced at the workshop on comic strip design about ancestral narratives (Trans. Origin of the Misak Community).

Figure 5 Week of Ancestral Languages Snapshots at Universidad del Valle (2019)

The Week of Ancestral Languages was meaningful for students since they expanded their views of language and could engage in dialogue with members of Indigenous communities. They understood that although English is an important semiotic resource, in our country, there is a wealth of languages and cultural practices that are unknown to them. This first encounter with Indigenous communities’ cultural semiotic resources and their meanings was the first step toward potential engagement in intercultural dialogue characterized by openness, respect, and commitment to maintaining the university’s linguistic and cultural diversity. These activities crystalize decolonial actions in that they intended to re-source Indigenous communities’ semiotic resources. This event also made the general student population aware of the cultural, cosmogonic, and epistemic richness of our Indigenous pueblos and the underlying politics of invisibilization to which these populations have been subjected.

Facilitating intercultural dialogue can also be enhanced at the investigative level. As an illustration, the reflections in this article are the result of a research study in which the CIU and teachers of the foreign language department at our university collaborated (Álvarez Valencia & Miranda, 2022). The study makes part of a macro-project that aims to increase Indigenous students’ retention and graduation rates. In designing the study, we thought that one way to engage in critical intercultural dialogue and to construct a decolonial way of conducting research was by working together with Indigenous students throughout the research process (research design, data collection, and analysis) and by shifting the traditional objectifying interactional dynamics between researchers and participants. Although space limitations preclude delving into the findings of the project’s first stage (see Álvarez Valencia et al., 2021), the emphasis here is the possibility of promoting and facilitating intercultural dialogue through research.

Although there may be more actions to enhance intercultural dialogue in educational institutions, we point to the most meaningful based on our experience at Universidad del Valle. Figure 6 synthesizes the barriers and actions that can be implemented to promote intercultural dialogue.

Conclusion

Integrating a decolonial and an intercultural perspective in education is still a challenge since education is still grappling with understanding what these two perspectives mean and how they can be articulated, not only at the curriculum level but also at the practical level in the classroom. In this reflective paper, we discuss some of the main barriers Indigenous students face in HE and propose actions that stakeholders and teachers could undertake to facilitate their permanence and engagement in sustainable intercultural dialogue. Our observations and proposals emerge from our experience as teacher educators in a public university in Cali, one of the most diverse cities in Colombia. We also draw on the research conducted with Indigenous students, and, most importantly, we are inspired by their narratives and the moments shared with them in our classes and as part of the activities of the CIU.

Reaching equitable access to HE for Indigenous students requires a concerted effort that includes multiple stakeholders. From the administrative perspective, conditions should be provided for Indigenous students to complete their degrees, including proper counseling and academic accompaniment. Additionally, universities must design strategies that facilitate students’ access to information about their programs and guidance on how to submit applications. At the curricular level, teachers are called to increase the presence of Indigenous students’ cultural practices, cosmogonies, and epistemologies that would contribute to the recognition of their semiotic resources. Overall, the university campus should be an open space for the manifestation of Indigenous students’ political and cultural activism, inviting the academic community to intercultural encounters and dialogue. Spaces for intercultural encounters are essential since institutional rulings can change the status of minoritized groups on paper, but they cannot permanently remove the colonial mindset of individuals. Actual intercultural exchanges and negotiation of cultural semiotic resources are central to engagement in intercultural dialogue.

We propose to adopt principles of multimodal pedagogies, critical pedagogies, and asset-based pedagogies to re-source Indigenous students’ languages and ways of being and learning. These pedagogies allow classrooms to become equitable spaces where recognition, inclusion, and social justice are discussed and embodied. More work must be done in incorporating principles from these pedagogical proposals into various courses across the curriculum. This opens avenues for research that explore: How can a decolonial perspective and asset-based pedagogies be integrated with different curriculum areas? What decolonial activities, materials, and strategies can be designed in foreign language classes? What kinds of semiotic resources of minoritized communities should be included in the curriculum? What tensions do teachers and students face in integrating a decolonial perspective in their classes? These and many other questions emerge as we consider decolonial intercultural education’s possibilities.