Introduction

When it’s corrected by the teacher, we don’t really analyse what was highlighted, if the teacher corrected, there has to be something wrong there; whereas, when a peer, at the same level we are, corrects it, we really ponder whether there is something wrong. (Participant from a previous study)

We were collecting data for a previous study on peer feedback (Zaccaron & Xhafaj, 2020) when a few students did not meet the deadline for handing in their texts; consequently, their essays could not be analysed by a peer and considered for that study. Nonetheless, the first author, their English teacher, decided to provide feedback to those students but forgot to mention that the feedback was not from a peer. Although their data were not included, they also completed a questionnaire to analyse their perception. As seen in our epigraph, their answers were puzzling, considering that when we analysed their uptake of that feedback-provided by the teacher, but they did not know that-the rate was quite similar to the ones who received peer feedback. This view raises pertinent issues concerning one’s engagement with the feedback and triggered the present study. Here, a group of students received feedback provided by the English teacher but thought a peer had provided it, while the second group received peer feedback.

Several studies have investigated different formats, timing, and the emotions involved in both teacher and peer feedback (Chang, 2016; Cui et al., 2021; Mahfoodh, 2017; Salih, 2013; Wu & Schunn, 2020; Zaccaron & Xhafaj, 2020; Zheng & Yu, 2018), while a few studies have looked at the influence of social representations of teachers (Castro, 2004) and classmates in the learning process. However, in the English as an additional language (EAL) field, there is a lack of research on the intersection between these two areas. This action can contribute to the field of feedback on writing as social representations show avenues to understand individual representations and attitudes to a social object (Wachelke & Camargo, 2007).

In our study, this social object is students’ feedback on their texts. Therefore, our objective is to analyse bias in peer feedback. To do so, we investigate the effect of teachers’ and peer social representations on EAL writing through learners’ behavioural engagement with teacher feedback disguised as peer feedback.

Brief Overview of Teacher Feedback and Peer Feedback

As feedback is a vital tool for learning (Carless & Boud, 2018; Hattie & Timperley, 2007), the last two decades saw considerable new research on feedback on L2 writing (Yu & Lee, 2016). In these studies, feedback was teacher-led (Ferris, 2006; Mahfoodh, 2017), came from a peer (Côté, 2014; Hu & Lam, 2010), or encompassed both modalities (Cui et al., 2021; Liu & Sadler, 2003; Lu & Bol, 2007; Maldonado-Fuentes & Tapia-Ladino, 2019; Ruegg, 2015; Yang et al., 2006). This study builds on previous research by investigating the effect of teacher and peer feedback with a specific focus on how the social representation of these actors might play a role in the behavioural engagement learners have with feedback, as well as their perception of the process.

Teachers are expected to provide feedback to students (be it orally or in writing). Moreover, students are usually frustrated if they do not receive it (Hyland & Hyland, 2006; Shrum & Glisan, 2015). In this respect, learners perceive teacher feedback as more trustworthy than peer feedback, and its usefulness is generally not questioned (Chang, 2016; Liu & Wu, 2019). One of the reasons for this belief might be what Ruegg (2015) found when she compared the differences in uptake of peer and teacher feedback with tertiary-level students in Japan-teacher feedback was more specific. Also, learners paid more attention to it and accepted it more often than peer feedback.

On the other hand, teacher feedback-the most frequent in EAL classes-can also have a few caveats. For students, finding their essays full of teacher feedback can be an emotionally frustrating and discouraging experience (Lee, 2014; Mahfoodh, 2017), which can affect their behavioural engagement with feedback. Moreover, it is not uncommon for learners to exert a more passive role in accepting surface-level feedback (Yang et al., 2006), as teachers at times focus more on a narrow range of linguistic aspects that do not always equate to the students’ needs or, contrary to Ruegg (2015), give vague feedback (Cui et al., 2021). Likewise, Lee (2014) warns that students can also have perfunctory engagement with teacher feedback that focuses on the product rather than the process.

Peer feedback has learners as sources of information and shifts the teacher-students’ typical roles (Liu & Edwards, 2018). Typically, this type of feedback is believed to encourage collaboration (Zaccaron & Xhafaj, 2020), present suggestions and techniques for improving one’s work, and allow for exposure to various writing styles (Ho & Savignon, 2007). In this respect, Hyland and Hyland (2006) argue that peer feedback helps novice writers understand how readers see their work. However, Ho and Savignon (2007) and Zaccaron and Xhafaj (2020) warn that sometimes hostility can arise during face-to-face feedback sessions. Additionally, if they are used to receiving this feedback, peers can focus their assessment mainly on the form (Maldonado-Fuentes & Tapia-Ladino, 2019). Furthermore, the perception of peer feedback usefulness might not equate to performance on writing revisions (Strijbos et al., 2010), and peer feedback might not meet the writer’s expectations (Salih, 2013).

More recently, a strand of studies explored affective variables that affect the effectiveness of corrective feedback. Chen and Liu (2021), who investigated teaching Chinese as a second language, highlight that empathy, cultural stereotypes, and learners’ emotions influence how teachers perceive the effectiveness of written feedback. Learners’ emotions are pivotal for learners’ (dis)engagement with peer feedback. Still, on contextual variables that may impact learners’ perception of feedback, the notion that culture and context play a relevant role in the feedback process has been indicated in teacher feedback (Cheng & Zhang, 2021) and peer feedback (Bolzan & Spinassé, 2016) studies.

Furthermore, Zaccaron and Xhafaj (2020) reported that although learners valued peer feedback, they preferred teacher feedback as peer feedback could not generally be trusted, which triggered them to reflect more when analysing this type of feedback. Finally, proficiency level in the additional language might influence the engagement with peer and teacher feedback (Hu & Lam, 2010; Liu & Wu, 2019; Zheng & Yu, 2018). Thus, there is a call for more studies to investigate learners’ perceptions of what they believe to be effective for them and teachers’ beliefs-which are part of social representations-about what works for learners.

Finally, Ruegg (2015) points out that when receiving both peer and teacher feedback, learners, not surprisingly, prefer teacher feedback, as the teacher will evaluate and mark the final version of their writing. This way, she is signalling that, for studies to investigate teacher and peer feedback, they should employ different strategies to avoid this possible bias.

Social Representations in the EAL Classroom

A challenge teachers face is understanding the kind of representations learners bring to the classroom (Chaib, 2015). In this respect, Vale et al. (2018) mention that the interaction between teachers and students is crucial in educational contexts and that such an interaction is based on the social representations these actors have. Therefore, understanding how these social representations impact learning cannot be underestimated (Castorina, 2017). As the feedback process involves the other, it is unsurprising that it is mediated by learners’ representations of the feedback giver. This impact was explicit in the excerpt by a previous participant in our epigraph.

According to Jodelet (2001), social representation is a form of socially created and shared knowledge. It has a practical application as it affects behaviour, allows communication, and helps construct a reality common to a social whole. These representations are not static but based on previous knowledge triggered by a given social situation. Almeida and Santos (2011) and Vale et al. (2018) highlight communication’s paramount importance for social representation.

According to Chaib (2015), to understand the learning process from a social representation perspective, one has to look at the social relationship between the teacher and learners. From the teachers’ perspective, Fernandes’ (2006) study on social representations and identities of English teachers in Brazil interviewed four teachers who felt their proficiency in the additional language was not good enough compared to native speakers. Consequently, they felt insecure as they believed teachers could not make mistakes. Fernandes (2006) argues that such a position indicates the notion of the role model teacher who knows everything and is solely responsible for students’ learning.

While there are a few studies on the social representation of English teachers in Brazil, most studies had learners as participants. They also focused on the representation of the English language (e.g., Michels, 2018). An exception is Castro (2004), who investigated the role English learners attributed to themselves in the learning process. Her results indicated that while learners credited their successes to the teacher, shortcomings were attributed to themselves. Moreover, learners tended to ignore the importance of their participation and of playing a more active role in their learning process, highlighting that topics, activities, and resources chosen by the teacher played a relevant role in their learning. The social representations found by Castro indicate a traditional view of learning in which teachers and students have clear roles. Not only is the teacher represented as the one who manages the activities, but also as the one who manages most of the students’ learning process.

Finally, as for how social representations of the source of feedback affect the extent to which this feedback is trustworthy, Mayo (2015) argues that the concepts of trust and distrust are not simple contraries. That is, not trusting a source does not necessarily mean one rejects it entirely. The grey area leads to a sense of distrust that considers both scenarios possible, making reactions more complex (Mayo, 2015).

Despite a large body of research that studied teacher and peer feedback on writing in EAL contexts, no study investigated the impact social representations of teachers and peers have on their engagement with feedback. Thus, drawing on previous studies and addressing this gap, the following research questions guide this mixed-methods study:

Method

We adopt a mixed-methods approach to research by combining quantitative and qualitative data (Dörnyei, 2007). By triangulating the data, we aim to explore different aspects of the dataset to answer our research question.

Participants and Context

Data were collected over a semester in an extension programme in a Brazilian university that offers additional language courses as an outreach activity, among them English. Most learners are either graduate or undergraduate students from the same institution. The English course lasts five years, and each semester encompasses 15 weeks of two 90-minute classes per week.

Thirty-two learners taking the EAL course in two groups participated in this study. The participants were at the intermediate level1-B1 level according to the Common European Framework-and taught by the first author, who had been teaching EAL at the university for four years. Only learners who completed their first essay (teacher feedback) before the second essay (teacher or peer feedback) had their data included in the study.

Instruments, Procedures, and Data Collection

Learners wrote two essays during the course. For Essay 1, in pairs, they were instructed to take notes while interviewing each other in class. Afterwards, they had to write a short narrative text at home to introduce their peer. Teacher feedback on this text also served as a model for indirect feedback.2 Before Essay 2, learners had a short training for peer feedback, as training is essential for its success (Chang, 2016; Min, 2005). Although longer and more elaborate training is ideal, we agree with Hu and Lam (2010) when they warn that the classroom requires adaptations, especially a course not solely focused on writing such as ours. Therefore, a 30-minute training activity occurred in class a week before learners engaged in giving feedback. During this training, in pairs, they had to give form-focused feedback on a paragraph provided by the teacher using the colour code scheme used by the teacher in their previous essay and add comments about content and structure. The teacher monitored and helped pairs during the activity, which ended with a discussion on some outstanding issues that a few learners had.

Essay 2 was a short expository text about a TED Talk of their choice. The teacher presented the TED website and its main features in class, as some students were new to it. For homework, they were instructed to watch as many TED Talks as possible, find one they liked, and write a short essay about it. This text (120-180 words)3 had to contain a title, a summary of the main points of the video, as well as their reasoning for their choice. With the instructions for the essay, the teacher also emailed his essay to serve as input/model. Finally, the students were asked to keep the reader (their peer) in mind when writing.

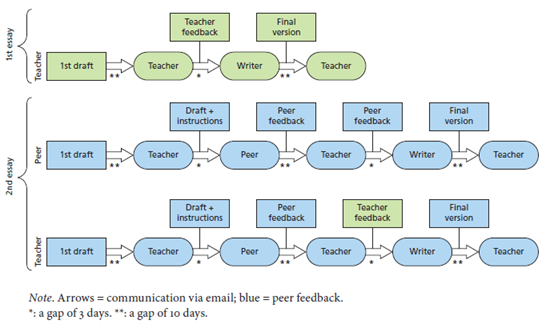

Most EAL learners in this course had not had the opportunity to rewrite their text before. Therefore, instructions in class and an email detailed the text requirements and the steps they followed. As for anonymity, all authorship information was removed from the files before randomly assigning them to another learner. The only information remaining in the essays was a number so the teacher could keep track of reviewers and reviewees. Figure 1 describes the steps for data collection.

During the ten-day interval, learners had to provide feedback; the teacher randomly chose half of the essays to give feedback himself. After learners emailed the teacher the feedback for their peers’ text, all authorship information was deleted from these files that were emailed back to the writers. All students received their revised text at the same time. Furthermore, they believed they were receiving feedback from a peer, even though half of them had feedback provided by the teacher, a design facilitated by electronic feedback (Ene & Upton, 2018). Finally, learners had three days to consider their feedback and submit their final versions for teacher evaluation.

After the students emailed the teacher their revised essay, they were asked to complete an attitudinal questionnaire on Google Forms (see Appendix) to unveil their perceptions of giving and receiving peer feedback. Questionnaires in Brazilian Portuguese were chosen over interviews due to time restrictions, as grades had to be assigned quickly. We considered that having the grades could affect learners’ perception of the process (Best et al., 2015). Although we acknowledge that questionnaires present some limitations to grasping complex issues (Dörnyei, 2010), mainly the time allocated for completion, they remain a popular instrument to collect data on the perception of peer feedback (Chang, 2016; Wu & Schunn, 2020). The questionnaire had Likert-type items (three questions with six options) and some open-ended questions and was previously tested and used by Zaccaron and Xhafaj (2020).

Data Analysis

The quantitative data resulted from coding the feedback writers received for their essay draft and its uptake on the final version of the same text, which indicated learners’ behavioural engagement with feedback.

In line with Conrad and Goldstein’s (1999) proposal, all types of feedback were analysed to see whether they were (a) not revised, led to (b) successful, or (c) unsuccessful revisions. This step follows the same procedure employed by Mahfoodh (2017) and Yang et al. (2006).

A second analysis of our quantitative data compared the feedback provided and its uptake on the final versions of Essay 1, for which only the teacher gave feedback, and Essay 2, in which half of the group received teacher feedback but believed that a peer had given it, and half of the group received peer feedback.

Coding the quantitative data started with a preliminary practice involving both researchers, each coding eight essays with 101 tokens (feedback). The level of agreement reached using SPSS was a Cronbach alpha of 0.766, which is acceptable considering the three possible outcomes (taken up successfully, unsuccessfully, or not addressed) for the two variables (lexis and grammar). Then, the first author coded the remaining feedback, and the second author reviewed it. Instances of disagreement were discussed until agreement was found. Despite trying to keep consistency during the analysis (i.e., coding data in a short time), we acknowledge the subjectivity of such an approach as a limitation. Next, two excerpts exemplify the coding process for behavioural engagement with feedback.

The reviewer highlighted two grammar errors in this passage. We discussed that the second error could also have indicated a vocabulary issue. However, the colour used indicated the focus on the tense.

Although they have only 16 neurons, it’s eight per eye that say exactly where the target is.

Below, in the revised text sent to the teacher, we counted one successful (says) and one unsuccessful uptake (it is).

Although they have only 16 neurons, it is they are eight per eye that says exactly where the target is.

Finally, to understand EAL learners’ perception of the feedback process, qualitative data gathered through the questionnaire were analysed inductively using a reflexive thematic approach, identifying patterns across data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Data were approached deductively (based on previous descriptors in the literature) and inductively, as new categories were identified in the data (Miles et al., 2014). Then, the analysis process using ATLAS.TI software version 22.1.5 facilitated the identification of recurrent themes and interconnected patterns. For instance, this process allowed us to link several actions taken by learners (e.g., analyse feedback, compare with different sources, and consolidate knowledge) to the first theme, “Research Triggered by Insecurity May Lead to Autonomy.” Additionally, considering cross-cultural issues in multilingual research (Thompson & Dooley, 2019), the qualitative data in this paper were translated into English by two professional translators and the two authors. Differences in these translations were discussed until we agreed on a solution.

Ethics

Ethics was a sensitive issue for this study. The idea of providing teacher feedback presented as peer feedback was deemed justified considering that (a) teachers possess more advanced knowledge of the additional language than students; (b) therefore, teacher feedback would not negatively impact students’ revised essays; and (c) the adopted design was the only possibility to investigate possible bias in feedback uptake. Furthermore, this study was approved by the institutional research ethics committee. Participants were provided with enough information to decide whether to participate voluntarily in the study. Finally, the handling of identifying information guaranteed confidentiality. Six participants either missed deadlines or did not consent to the study, and their data were not included.

Results

Quantitative Data

To answer our first research question, we compared the percentage of uptake (Tables 1, 2, and 3) for Essay 1-teacher feedback identified as such-and Essay 2-experimental condition.

Table 1 Proportions of Suggestions and Take-up Rates (Essay 1)

| Measure | Lexis | Grammar | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| N. of suggestions | 32 | 340 | 372 |

| Suggestions taken up successfully: n (%) | 25 (78.12) | 282 (82.94) | 307 (82.53) |

| Suggestions taken up unsuccessfully: n (%) | 5 (15.62) | 42 (12.35) | 47 (12.63) |

| Suggestions not addressed: n (%) | 2 (6.25) | 16 (4.71) | 18 (4.84) |

Table 2 Proportions of Suggestions and Take-up Rates (Essay 2: Teacher Feedback Disguised)

| Measure | Lexis | Grammar | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| N. of suggestions | 29 | 268 | 297 |

| Suggestions taken up successfully: n (%) | 15 (51.72) | 167 (62.31) | 182 (61.28) |

| Suggestions taken up unsuccessfully: n (%) | 4 (13.79) | 32 (11.94) | 36 (12.12) |

| Suggestions not addressed: n (%) | 10 (34.49) | 69 (25.75) | 79 (26.60) |

Table 3 Proportions of Suggestions and Take-up Rates (Essay 2: Peer Feedback)

| Measure | Lexis | Grammar | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| N. of suggestions | 21 | 124 | 145 |

| Suggestions taken up successfully: n (%) | 11 (52.38) | 82 (66.13) | 93 (64.14) |

| Suggestions taken up unsuccessfully: n (%) | 3 (14.29) | 13 (10.48) | 16 (11.03) |

| Suggestions not addressed: n (%) | 7 (33.33) | 29 (23.39) | 36 (24.83) |

While the percentages for unsuccessful uptake were similar, 12.6% for Essay 1 and 12.1% and 11% for Essay 2, the percentage of not addressed feedback showed a substantial difference, as only 4.8% of suggestions for Essay 1 were disregarded. In contrast, for Essay 2, this number rose to 26.6% of suggestions when they were from the teacher disguised as peer feedback and 24.8% of peer suggestions. There were instances where teacher feedback (Essay 1) led to errors, possibly for being unclear (Cui et al., 2021); nonetheless, learners addressed these instances and made changes where indicated by the teacher. When it comes to the feedback they thought was from a peer, distrust, possibly fuelled by the social representation of students of English, seemed to lead learners to ignore a much higher number of suggestions.

In sum, the answer to our first research question (Is there a difference in the behavioural engagement with teacher feedback when presented as peer feedback?) is that the percentage of suggestions taken up for teacher feedback disguised as peer feedback and peer feedback is quantitatively close.

Qualitative Data

Following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis procedures, we identified three broad themes for our qualitative data.

Research Triggered by Insecurity May Lead to Autonomy

Learners indicated the feedback process to be demanding, mainly due to feeling insecure. While they reported insecurity about both the peer feedback they received and the feedback they gave to a peer, students also assessed this emotion to be a trigger for further research, as Lucia4 mentioned: “As we weren’t sure . . . we had to look things up, do some research and study.” As a result, learners employed more strategies (e.g., checking different sources) than they would typically do when dealing with teacher feedback: “It leads us to verify (in other sources) whether that point/observation is accurate” (Jorge). Overall, students reported high behavioural engagement with peer feedback, especially considering that “analyse,” “compare,” and “research,” as a group, were the codes with the highest presence in the data.

Furthermore, participants acknowledged that this activity demanded more time and effort than they were used to in the English class: “It was a trabalheira [much work] giving this feedback, I read my classmate’s text about a thousand times” (Catarina). The use of trabalheira, a hyperbole for the word “work,” echoed a feeling expressed by many students, that is, their high behavioural and cognitive engagement with the tasks was the result of the challenge posed by the activity, which a few learners reported to be beyond their language competence. This might be due to the sense of responsibility to their peer: “I don’t want to be unfair, and at the same time, I want to show that I noticed something that isn’t so clear in the text” (Gabriel). In other words, similar to Hu and Lam (2010), our participants were worried their feedback could mislead their peers; hence, they spent more time analysing it. Learners indicated this extra work could positively influence their future production in English, as Joice mentioned: “to analyse the common mistakes that are made and try to avoid them.” This statement shows that some learners benefited from feedback by playing a more active role.

Similarly, learners were asked whether they engage differently with teachers and peer feedback. As reported in the literature (Chang, 2016), they trusted teacher feedback more. Concerning our research question on behavioural engagement, peer feedback resulted in high engagement, as mentioned by Leandro: “A search/reflection, which would probably not happen if the teacher pointed out the mistakes directly. After all, if the teacher says something, that’s it, period!” This contrasting attitude towards the source of feedback (peer or teacher) gives a glimpse into how the social representation of these actors affects the process of an activity that shifts the role of authority in the classroom to students, such as peer feedback.

Additionally, it shows a more traditional social representation of teachers, similar to Vale et al. (2018). According to Wachelke and Camargo (2007), social representations serve as a guide to actions. In our study, this seems to have resulted in a more critical lens applied by students to peer feedback. Teacher feedback disguised as peer feedback received the same treatment.

In sum, despite feeling unsure about their peer feedback, at times, learners displayed a certain level of autonomy as they not only carried out research to give and analyse their peer feedback but also compared to their current production and indicated this could have an effect in the future, enhancing their learning. To summarise the positive aspect of researching more due to uncertainty, Moira mentioned: “It gives me the autonomy to pursue learning.”

More Attention to Errors

Some students indicated that the higher attention required in the activity could benefit their future texts: “It makes us more attentive not to make the same mistake again” (Jorge). A high level of attention was required to analyse whether the feedback they received was appropriate to the context: “I had a little more work because I had to find out if that correction was right or not” (Luana). Additionally, the attention reverberated on their essays: “In a way, I am more attentive when writing mine (text)” (Maria). These remarks, by different learners, highlight that calling one’s attention to errors was perceived as one of the main benefits of the peer feedback process.

Moreover, attention was indicative of high behavioural and cognitive engagement with peer feedback, as seen in the following excerpt by Joana: “I had to filter those corrections/comments that seemed plausible; this way, I found the mistakes I had made and kept the structures which I considered correct.” Judging feedback, an essential aspect of feedback literacy (Carless & Boud, 2018), is a highly demanding cognitive action, as the peer’s views trigger an evaluation of the feedback and their own text. Another point from Joana’s answer is that learners, in general, were more prone to exercise their agency when dealing with peer feedback, as they evaluated feedback and decided to keep what they judged appropriate. Ana highlighted that the attention and effort required was a rupture from the general tasks in class: “It takes us, as students, out of our comfort zone.” Such a process contrasts with their take on teacher feedback, which is taken at face value, as seen previously in Leandro’s answer.

Having the chance to rewrite their text after feedback was something new to learners; they, therefore, highlighted the benefits of acting upon their errors and producing a new revised text: “Having the possibility to rewrite is very important so that we can correct our mistakes and not just observe what mistakes we make.” Here, Felipe points to the crucial element of acting upon feedback (Hattie & Timperley, 2007) instead of simply receiving feedback. This view aligns with Carless and Boud’s (2018) stance that feedback not acted upon is simply information and, as such, does not have the same impact on learning. Moreover, with that statement, Felipe hints that engagement with feedback is not as high when no resubmission is required. By paying close attention to errors when rewriting their first draft, learners indicated they judged peer feedback and mainly filtered what was appropriate to their text.

Higher Engagement With Peer Feedback

Giving and receiving feedback from a peer had benefits beyond reading different writing styles, as seen in Ho and Savignon (2007). Pre-intermediate students seemed to benefit from observing areas for improvement and successes in local textual issues, as seen in Luciana’s position: “When you write something, especially in another language, it’s important to have different points of view to notice mistakes and successes.” Here, she highlights two aspects of this activity. First, writing in an additional language is demanding, and having diverse viewpoints, other than the teacher’s, on linguistic aspects that can be improved is beneficial. The second aspect is that she could realise, through peer feedback, her accomplishments as a writer in the additional language.

Additionally, participants mentioned they could benefit from perceiving errors in their peer’s text. Rodrigo, for instance, said:

It was an exciting way of learning because, until then, I had been learning from my own mistakes. With this new action, I could learn from the mistakes of others and realise that they were mistakes that I would also make.

Rodrigo indicates that by looking at someone else’s text and errors, one can identify patterns and perceive constructions similar to one’s own (Shrum & Glisan, 2015).

Notably, although these learners were at the pre-intermediate level, they did not restrict their analysis to the word level. For instance, Julia mentioned that reading another form of organisation of arguments was enlightening: “It’s possible to perceive other ways of structuring arguments.” Still, beyond the word level, Moira adds: “It can bring new insights, ways of writing, and expressions that I can include in my future texts.” This positive view of learning linguistic aspects from a peer’s text aligns with Zhang and Hyland (2022), whose participants were happy to learn words and phrases in the peer feedback process.

Finally, to a few learners, giving feedback also served as a springboard to look for the video source for their peer’s text. Gus said he decided “to watch the TED Talk itself to understand what the text was about.” This went beyond the standard behavioural engagement with feedback and enhanced its exposition to include more input in English, which might benefit his learning.

Discussion and Implications

This mixed-method study proposed two research questions to investigate the impact social representations of teachers and peers have on EAL learners’ behavioural engagement with written feedback. Taken together, the quantitative and qualitative results suggest that the source of feedback is more relevant than the feedback itself for its processing by the EAL learners investigated in this study. Additionally, the triangulation of our data strengthens the idea that peer feedback fosters strong behavioural engagement as it seems to trigger more reviewing strategies. We argue that the social representation of peers elicited from the answers to the questionnaire-that is, of what a peer at the same level can do-seems to trump their positive individual experience in producing feedback for their peer and, in turn, influences their suspicious behaviour towards processing the feedback received. Even taking into account the fact that the teacher would grade the texts (Ruegg, 2015), there was a considerable difference in uptake for Essay 1 (teacher feedback) and Essay 2 (teacher feedback disguised as peer feedback). The trust, or rather the lack of it, in the source of feedback seemed to lead to a more critical analysis of feedback when participants thought it came from an anonymous peer.

As Mayo (2015) argues, not trusting does not necessarily equate to invalidating the other. In our study, distrust of peers seemed to bring about some positive actions (i.e., research and double checks) despite extra work and the negative emotions it generated namely uncertainty and anxiety. When comparing their approach to the first feedback they received (teacher feedback) and their answers from the questionnaire, our participants seemed to display a more passive role when processing teacher as opposed to peer feedback, corroborating Lee (2014) and Yang et al. (2006). Such a traditional approach to teacher feedback aligns with the social representations of English language teachers in Brazil found by Castro (2004). One may argue that this is obvious, considering the different roles teachers and students play in the classroom and the social representations of these groups. However, if we were to advance in offering a more student-centred approach to learning in the EAL context, should we not encourage students to apply a more thorough approach to teacher feedback, too? For teachers, the results also highlight that when the assessment focuses on the result rather than the process, learners seem to accept teacher feedback in a perfunctory manner.

It is important to emphasise that our objective is not to encourage learners to distrust teacher feedback, which is their default approach towards peer feedback. We argue that encouraging learners to apply similar analyses when they conduct peer feedback to teacher feedback might enhance their learning process, as they devote more attention to the feedback received and search other sources, enhancing their engagement. In fact, by revisiting our data from two years ago to write this article, there were a few instances when the teacher of the groups, the first author, found that some of his feedback was incorrect or too vague. This fact can happen for several reasons, be it time constraints of a fixed curriculum or high teaching workload (Cui et al., 2021). After all, the idea of teachers who are always right is a deeply ingrained myth, even by teachers (Fernandes, 2006). We are humans, so teachers sometimes give erroneous feedback despite avoiding it as much as we try. In sum, our argument is that teacher feedback should not be incorporated without reasoning, which, based on our results, often happens in the EAL context.

Another pedagogical implication is adopting peer feedback at all proficiency levels in general language courses. Despite a few adverse reactions it first generated, low-proficiency learners seemed to enjoy reading a peer’s text and giving and receiving feedback. In this sense, we disagree with Liu and Wu (2019) when they suggest peer feedback only for higher proficiency groups. We side with Miao et al. (2006), who argue that exposure to peer feedback is the key to its acceptance. Thus, more rounds of peer feedback and its adoption sooner rather than later in language courses could be an effective strategy to mitigate possible negative emotions involved in the peer feedback process.

Conclusion

Overall, this study shows that pre-intermediate English learners display similar behavioural engagement with teacher feedback when disguised as peer feedback as they do with actual peer feedback; in other words, the social representations of teachers and peers seem to bias their feedback processing. Regarding the concern of perfunctory engagement with feedback, peer feedback, though perceived as an activity that requires more work, was the type of feedback that triggered a series of cognitive strategies and was also perceived by some learners as a means that placed them in control of their learning. Researchers and teachers should consider the benefits of peer feedback for pre-intermediate learners and the best way to fit specific contexts and reap its benefits.

We agree that studies on written corrective feedback should consider the powerful influence of specific contexts (Cheng & Zhang, 2021). Thus, our findings should be carefully considered. First, this was an exploratory study with data from only one teacher. Second, it was impossible to bring any firm conclusions about the comparison between the way learners received feedback from the teacher in their first essay and the way they received feedback from the teacher (but which they thought was from a peer) in the second essay because we did not have an independent rater to analyse the feedback for its validity. Finally, our data came from the feedback process and a questionnaire. Future studies may employ different instruments, such as semi-structured interviews and stimulated recalls. This action would enrich the analysis of how learners perceive and approach teacher and peer feedback, considering the impact of authority and trust.