Introduction

In the era of English as a lingua franca, English as an international language, and world Englishes-when the ability to use this language for communication is considered a core skill that enables participation in educational and working milieus, and when the native-like pronunciation goal tends to be discouraged in favor of intelligibility-issues of pronunciation are worth addressing. Nevertheless, even though scholars have endorsed the need for empirical studies in the area of pronunciation teacher education (Burri, 2015), studies on second language teacher cognition regarding pronunciation are exiguous (Baker & Murphy, 2011; Murphy, 2014), and no studies, to our knowledge, have been conducted with preservice English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers in Ecuador. Against this backdrop, this study aims to analyze Ecuadorian EFL preservice teachers’ attitudes toward pronunciation models and targets, identity, and confidence after taking phonetics and phonology courses as part of a university teaching training program in Cuenca, Ecuador. Since pronunciation learning can trigger identity predicaments due to the close connection between accent, intelligibility, and speaker identity (Gatbonton et al., 2005), analyzing preservice teachers’ attitudes toward pronunciation issues can provide sound insights to understand and improve second language teaching training concerning pronunciation instruction.

Theoretical Framework

Research on attitudes, models of English, and identity in relation to pronunciation frame this study.

Teacher Attitudes and Identity

Teacher attitudes, along with beliefs, knowledge, feelings, perceptions, and thoughts, belong to the realm of teacher cognition, the “personal, unseen aspects of teachers’ work,” which exert a strong influence on teachers’ behavior and pedagogical practices (Borg, 2019, p. 1150). Likewise, teacher identity can also be considered part of teacher cognition since it is related to teachers’ beliefs, thoughts, perceptions, or feelings (Borg, 2019); however, according to Burri et al. (2017), cognition and identity should be considered as separate components of teacher learning that develop jointly. It is a paramount element of the teaching profession since it can lay the foundation for constructing teachers’ ideas on “how to be, how to act, and how to understand their work and their place in society” (Sachs, 2005, p. 15). Teacher identity is not a determinate, stable, unchanging feature but constantly constructed and negotiated based on the experiences teachers undergo (Macías Villegas et al., 2020). In fact, “the development of teacher identity is an ongoing process of interpretation and reinterpretation of who one considers oneself to be and who one would like to become” (van Lankveld et al., 2017, p. 326). Learning to teach directly influences teacher identity formation (Beauchamp & Thomas, 2009); therefore, the theoretical and practical knowledge learned in teaching training programs allows preservice teachers to shape and understand their role as teachers (Macías Villegas et al., 2020).

Models of English and Pronunciation Attitudes

According to Kirkpatrick (2006), three models of English can serve English language teaching in different contexts: the exonormative native-speaker model, the endonormative nativized model, and the multilingual or lingua franca model. Choosing the English variety to be used as a model for teaching and learning in the expanding circle, where English is a foreign language, and the outer circle, where English is one of the official languages of a country, has usually been not grounded on educational issues but on political and ideological considerations; therefore, teachers and learners, who are the direct users, do not often have a saying in the decision of the model to be used for teaching and learning (Kirkpatrick, 2006). Usually, the native-speaker model has been preferred for being a simple and cautious choice because of the tremendous amount of material available for teaching and assessment that uses native-speaker varieties, the consideration of these varieties as standard, the interests of influential media and publishing agencies, and the perceived superiority of such varieties over relatively new, nativized ones (Kirkpatrick, 2006). Although the native-speaker model has been recognized as the most appropriate model for learners who are interested in migrating to English-speaking countries and learning the culture of these countries (Brown, 2014), it has been emphasized that these learners are small in number since the majority of outer-circle and expanding-circle learners will use English to communicate with other nonnative speakers (NNS)(Kirkpatrick, 2006).

Instead of considering the standard English varieties-General American (GA) or General British (GB)-a “default” decision, many factors should be analyzed before selecting a variety of English for instruction: the particular teaching context, “student’s needs and goals, teacher’s expertise, and attitudes toward a particular variety of English” (Matsuda, 2019, p. 148). Indeed, learners’ attitudes toward the target language may directly affect the pronunciation type adopted by them (Bialystok & Hakuta, 1994) as well as their “learning choices and outcomes” (Setter & Jenkins, 2005, p. 5). Research on learners’ attitudes toward pronunciation and their relationship with pronunciation goals has yielded mixed results. For instance, Pullen (2012) observed that the more the EFL learners felt affiliated with their culture, the less they cared about achieving native-like English pronunciation. On the other hand, Georgountzou and Tsantila (2017) reported that although EFL learners highly valued their culture, they also had positive attitudes toward native English accents and wanted to achieve native-like pronunciation.

Regarding second language teachers’ attitudes, Monfared (2018) found out that English teachers in the expanding circle tend to highly value native-speaker pronunciation, considering it the best and only correct form, while English teachers in the outer circle tend not to strive for native-like pronunciation and value meaning conveyance instead. Chan (2018) reported that even though Hong Kong English teachers consider intelligibility a crucial factor in communication, their teaching practices aim at native-like pronunciation, especially regarding assessment criteria. In general, teachers, learners, and educational authorities, especially in expanding-circle contexts, still prefer a standard native-speaker variety, mainly GA or GB, as the model of pronunciation (Jenkins, 2007; Rogerson‐Revell, 2011) without careful consideration of the attitudes that learners hold toward these prominent world accents (Brown, 2014). In Ecuador, an expanding-circle country, English is part of the primary, secondary, and higher education curriculum. Although the English pronunciation model for instruction is not stated in official documents, it is usually a native-speaker model, either GA or GB. Likewise, in universities where EFL teaching majors are offered, those pronunciation models are preferred.

Linguistic Identity and Pronunciation

Linguistic identity is related to language attitudes, ideologies, and linguistic power, and in postmodern societies, the complexity of these interrelations is increasing (Jenkins, 2007). Since very few L2 learners manage to attain native-like pronunciation in the target language, it is not deemed an achievable goal, and thus, pronunciation research has focused on intelligibility rather than accent (Derwing & Munro, 2015). Indeed, the achievement of intelligibility is claimed to be more important than both accent reduction and the attainment of native-like pronunciation (Isaacs & Trofimovich, 2012). Likewise, the global spread of English (meaning that it is used either as a second language or as a lingua franca by speakers who outnumber people who use it as a first language) and, thus, its global heterogeneity have increased the interest in world Englishes research and impacted the English language teaching field (Matsuda, 2019), suggesting new teaching approaches that foreground and develop learners’ intelligibility while allowing them to preserve and show their identity when speaking (Jenkins, 2007).

Speaking is an identity act since speakers, through the choice of language or language variety, reflect their “social and ethnic solidarity or difference” (Le Page & Tabouret-Keller, 1985, p. 178) and reveal both speakers’ self-images and the images they want other people to perceive (Pennington, 2019). As a major component of speaking skills, pronunciation is related to identity since it depicts how speakers want to present themselves individually and collectively (Pennington, 1997). For instance, “L2 speakers actively adjust pronunciation in order to express different meanings, to style speech, and to convey different facets of their identity and affiliations with valued others” (Pennington, 2019, p. 374). Therefore, ethical issues can arise when L2 learners attempt to acquire native-like pronunciation since they can feel that the direct relationship between their culture and mother tongue is at risk (Dalton & Seidlhofer, 2001). Golombek and Jordan (2005) analyzed how two Taiwanese preservice teachers in a pronunciation teaching program developed their teacher identities. They noted that it was fundamental for them to acknowledge themselves as legitimate English speakers to develop as pronunciation teachers. Burri et al. (2017) studied the development of teacher identity and cognition in a pronunciation-teaching post-graduate course. The findings revealed that NNS teachers started to see themselves as legitimate English teachers thanks to the pronunciation knowledge they acquired in the course.

Another pronunciation issue related to NNS teachers’ identity formation is pronunciation confidence (Park, 2012) since it affects EFL teachers’ attitudes toward pronunciation teaching. Uchida and Sugimoto (2019) revealed that EFL teachers are more likely to hold positive attitudes toward pronunciation teaching and tend to think that it is crucial and effective when they are confident in their pronunciation. However, NNS teachers tend to be insecure about their pronunciation, making them avoid teaching pronunciation (Murphy, 2014). Couper’s (2016) study indicated that Uruguayan EFL teachers are anxious about their NNS pronunciation and thus avoid teaching certain aspects, such as suprasegmentals.

Most of the studies above have been conducted with in/preservice teachers learning pronunciation pedagogy; however, no studies were found with NNS preservice teachers after taking phonetics and phonology courses. This study aims to address the following research question: What factors underlie Ecuadorian EFL preservice teachers’ attitudes toward English pronunciation issues after taking phonetics and phonology courses?

Method

Context and Participants

This study was conducted in February 2022 at a university in Cuenca, Ecuador, with students who had just finished the fifth and seventh semesters of an eight-semester EFL teaching training program. The content of the teaching program curriculum covers three main areas: linguistic knowledge (e.g., reading and writing, conversation, phonetics, phonology, pragmatics), teaching skills (e.g., TEFL, applied techniques and resources for teaching EFL, among others), and practicum (e.g., community outreach practice and teaching practice). English Phonetics is part of the fourth-semester curriculum, while English Phonology is of the fifth. The preservice teachers who had just finished the first and third semesters were excluded from the study since they had not taken those subjects yet. This selection criterion was based on the consideration that these courses have impacted the preservice teachers’ attitudes toward pronunciation and their identity formation as teachers (Macías Villegas et al., 2020). The Phonetics course revolves around the following topics: phonemes, allophones, syllable stress, consonant and vowel sound description, recognition, and production, while the Phonology course focuses on weak forms, consonant clusters, connected speech, sentence stress, and intonation. Although the pronunciation model adopted for the courses is GA, the preservice teachers are also exposed to some GB.

Of 75 preservice teachers who had just finished the fifth (n = 43) and seventh (n = 32) semesters, 70 agreed to complete an anonymous online questionnaire.

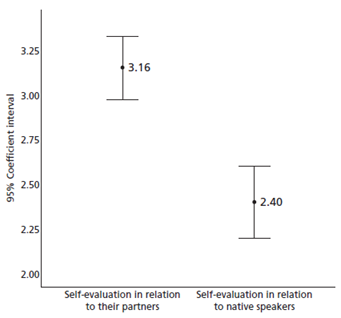

The participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 32 years (M = 22.13, SD = 2.32), and most were women (74.2%). Only 32.9% reported taking extra English classes and 8.6% living in an English-speaking country. Half of the participants mentioned that they never or hardly ever use English as a medium of communication outside the university classroom, while 38.5 % use it sometimes. For 77.4% of the participants, reaching a high English proficiency level is very important. Regarding their English overall proficiency self-evaluation, on a 1-5 scale, the mean value was 3.16 compared to their peers, but it was 2.40 compared to native speakers (see Figure 1).

Research Design

The study follows an explanatory sequential mixed-method design. The qualitative data contributed to gathering deeper insights and a deeper understanding of the quantitative data (Creswell, 2014).

Data Collection

Instrument

A self-report questionnaire was developed to study preservice teachers’ attitudes toward pronunciation issues after taking phonetics and phonology courses. Demographic and background information was elicited in the first section: age, gender, English training, living in an English-speaking country, use of English, English proficiency self-evaluation, the importance of a high English proficiency level, and the reasons for having decided to enroll in the EFL teaching training program.

The second section contains 29 five-point Likert-scale questions that elicit attitudes regarding native-speaker and NNS pronunciation models, English pronunciation ability and confidence, identity, and native-speaker and NNS pronunciation teachers, which were taken from Chan (2018), Georgountzou and Tsantila (2017), Monfared (2018), Uzun and Ay (2018), and Uchida and Sugimoto (2019). In addition, two open-ended questions are included: the first one asks the participants to write a paragraph about how their identities are affected when trying to pronounce English like a native speaker, while the second one prompts the participants to write a paragraph to explain how speaking like a native speaker will help them in their future.

The questions were written in Spanish and pilot-tested with two university students of different majors whose comments helped to adjust some questions. The anonymous online questionnaire was sent to the participants right after they had finished the academic semester to avoid any conflicts of interest that could have arisen because one of the researchers was the lecturer of the Phonetics and Phonology courses. At the beginning of the questionnaire, for ethical purposes, it was clearly stated that participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous, that it would not affect participants in any manner, and that agreeing to fill out the questionnaire also meant agreement for their data to be used for research purposes.

Data Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted with Jamovi software (the Jamovi Project, 2021). The adjustments to test the model validity (RMSEA, TLI, and χ²) followed Byrne’s (2016) guidelines. The dimensions are shown with their mean and standard deviation and are contrasted with average values and error bars.

The exploratory factor analysis yielded a five-factor solution. The suitability of the data for factor analysis was tested with the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (.664) as well as with the Barlett’s Test of Sphericity [X 2 (406 df) = 961; p ≤ .001]. The Principal Axis Factoring method was used for factor extraction along with the Varimax rotation technique. The five factors explain 48% of the variance. Factor loadings are .38 and higher, except for one item belonging to Factor 2 (loading of .285), which was retained because it contributes to explaining this factor. Internal consistency was determined by using Cronbach’s Alpha and McDonald’s Omega coefficients. The values were over .7 for four factors, indicating acceptable internal consistency, except for Factor 5, which can be because this factor comprises only two items.

Moreover, content analysis of the paragraphs written to answer the open-ended questions was used to identify emerging themes and patterns (Dörnyei, 2007). Two members of the research team analyzed the paragraphs. They were read thrice while extracts were highlighted in different colors, grouped, and labeled. The labels were compared to agree on the final categories.

Questionnaire Results

The five factors (Table 1) were labeled considering the strongest loadings (Loewen & Gonulal, 2015); therefore, the first factor, which consisted of eight items, was named Importance of the native speaker GA accent. Factor 2 was labeled Satisfaction with NNS pronunciation and included eight items; Factor 3 (with five items) was called Pronunciation confidence; Factor 4 (with four items) was named Native- vs. nonnative-speaker pronunciation teachers, and Factor 5 (with two items) was labeled Interest in the British accent.

Table 1 Five-Factor Solution for Attitudes Toward Pronunciation Issues

| M (SD) | Factor | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 1. Would speaking like a native speaker help in your future? | 4.59 (.69) | .769 | ||||

| 2. Is your English learning goal to sound like a native speaker? | 4.29 (.98) | .726 | ||||

| 3. Would you like to sound like a native English speaker? | 4.57 (.73) | .685 | ||||

| 4. Is pronunciation instruction important? | 4.84 (.43) | .674 | ||||

| 5. How important is it to you to pronounce English like a native American speaker? | 4.56 (.75) | .660 | ||||

| 6. Is it advisable for nonnative-speaker teachers to acquire native‐like pronunciation? | 4.20 (.91) | .611 | ||||

| 7. Do you try to pronounce English like a native American speaker? | 4.33 (.73) | .486 | ||||

| 8. Is pronunciation instruction effective? | 4.24 (.92) | .463 | ||||

| 9. Would you like to keep your nonnative accent when you speak English? | 1.99 (1.07) | .830 | ||||

| 10. Are you happy with your nonnative accent? | 2.67 (1.13) | .729 | ||||

| 11. Do you feel comfortable speaking English with apparent features of your Spanish native language? | 2.80 (1.04) | .551 | ||||

| 12. Do you think that speaking English with an Ecuadorian accent is acceptable for English teachers? | 2.97 (1.14) | .532 | ||||

| 13. Does it matter to you how your peers or interlocutors perceive your English pronunciation (if your pronunciation shows that you are not a native speaker?) | 1.91 (1.08) | .550 | ||||

| 14. Do you speak English with a nonnative accent? | 3.24 (.99) | .475 | ||||

| 15. Is it enough for nonnative-speaker teachers to have an English pronunciation that does not interfere with communication? | 3.21 (1.11) | .464 | ||||

| 16. Do you feel that if you pronounce English like a native speaker, your Ecuadorian identity is affected? | 1.37 (.8) | .424 | ||||

| 17. Is it acceptable that the pronunciation of English teachers has traces of their native accent (Spanish)? | 2.99 (1.07) | .285 | ||||

| 18. Are you confident in your English pronunciation? | 3.13 (.77) | .779 | ||||

| 19. How satisfied are you with your English pronunciation? | 3.33 (.6) | .681 | ||||

| 20. Do you think you are competent in English pronunciation? | 3.64 (.83) | .641 | ||||

| 21. Do you make conscious efforts to improve your English pronunciation? | 4.04 (.80) | .515 | ||||

| 22. Can native speakers of English easily understand your accented English? | 3.54 (.94) | .450 | ||||

| 23. When pronouncing certain sounds, do you make an effort to approximate the accent of a native English speaker? | 4.21 (.75) | .378 | ||||

| 24. Do you prefer a nonnative-speaker teacher to teach you English pronunciation? | 3.03 (1.10) | .765 | ||||

| 25. Do you think that a nonnative-speaker English teacher can teach pronunciation? | 4.1 (1.03) | .764 | ||||

| 26. Do you think that only native speakers should teach pronunciation? | 3.73 (1.19) | .673 | ||||

| 27. Do you prefer a native-speaker teacher to teach you English pronunciation?* | 2.21 (1.10) | .420 | ||||

| 28. Do you try to pronounce English like a British native speaker? | 2.39 (1.12) | .900 | ||||

| 29. How important is it to you to pronounce English like a British native speaker? | 2.93 (1.19) | .737 | ||||

Note. The principal axis factoring extraction method was combined with a Varimax rotation.

* This item was reversed since it logically contradicts the rest of the items but shows good saturation with the group of items

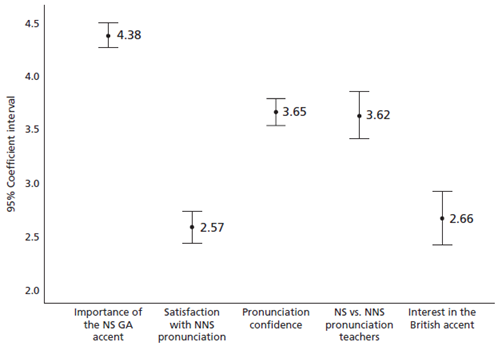

The mean of the five factors is shown in Table 2. As can be seen, the greater value was for Importance of the native-speaker GA accent while the lowest, for Satisfaction with NNS pronunciation.

Table 2 Descriptive Dimensions of Preservice Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Pronunciation Issues

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Importance of the native-speaker General American accent | 2.18 | 4.91 | 4.38 | .49 |

| Satisfaction with nonnative-speaker pronunciation | 1.11 | 4.78 | 2.57 | .65 |

| Pronunciation confidence | 2.33 | 4.83 | 3.65 | .53 |

| Native- vs. nonnative-speaker pronunciation teachers | 1 | 5 | 3.62 | .91 |

| Interest in the British accent | 1 | 5 | 2.66 | 1.07 |

An error bar chart was created to determine significant differences related to the variability of the dimensions. As shown in Figure 2, with a confidence interval of 95%, three groups of dimensions are differentiated significantly. The first group corresponds to Importance of the native-speaker GA accent with the highest mean (4.38). The second group comprises two factors: Pronunciation confidence (3.65) and Native- vs. nonnative-speaker pronunciation teachers (3.62). The last group encompasses Satisfaction with NNS pronunciation (2.57) and Interest in the British accent (2.66).

Spearman’s correlations were used to explore the relationship between the EFL preservice teachers’ pronunciation attitudes and some of their characteristics. As indicated in Table 3, the results reveal that Factor 1, Importance of the native-speaker GA accent, has a significant positive correlation with the variable Importance of reaching a high English proficiency level. In addition, Factor 3, Pronunciation confidence, shows a significant positive correlation with four variables: Frequency of English usage outside the classroom, Self-evaluation in relation to peers, Self-evaluation in relation to native speakers (Rho = .585), and Living in an English-speaking country. Lastly, Factor 5, Interest in the British accent, positively correlates with Extra English courses and Living in an English-speaking country.

Table 3 Spearman’s Correlation of the Five Dimensions

| Frequency of English usage outside the classroom | Self-evaluation in relation to their classmates | Self-evaluation in relation to native speakers | Importance of reaching a high English proficiency level | Extra English courses | Living in an English-speaking country | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Correlation coefficient | .121 | -.068 | .057 | .398** | .064 | .161 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | .324 | .576 | .64 | .001 | .597 | .183 | |

| N | 69 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | |

| Factor 2 | Correlation coefficient | .068 | .008 | .019 | -.161 | .227 | -.12 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | .58 | .947 | .878 | .183 | .059 | .322 | |

| N | 69 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | |

| Factor 3 | Correlation coefficient | .267* | .392** | .585** | -.007 | .041 | .263* |

| Sig. (bilateral) | .026 | .001 | 0 | .953 | .737 | .028 | |

| N | 69 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | |

| Factor 4 | Correlation coefficient | .073 | .078 | .124 | 0 | -.041 | .204 |

| Sig. (bilateral) | .553 | .521 | .308 | 1 | .736 | .09 | |

| N | 69 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | |

| Factor 5 | Correlation coefficient | .213 | .193 | .196 | .233 | .268* | .394** |

| Sig. (bilateral) | .079 | .109 | .104 | .053 | .025 | .001 | |

| N | 69 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

*Significant correlation at .05 (bilateral). **Significant correlation at .01 (bilateral).

Qualitative Data Findings

A content analysis of the open-ended questions was carried out to gain deeper insights into the quantitative data. Regarding the first question, which asks the participants to write a paragraph to explain how their Ecuadorian identities are affected when pronouncing like a native speaker, 94% stated that their identity is not affected at all. In fact, one central theme emerging from the analysis is the belief that their Ecuadorian nationality, cultural roots, customs, and identity are not affected when they pronounce English like a native speaker. The second central theme refers to the desire for improvement and mastering the English language, which makes them try to sound like a native speaker. The following excerpts written by some participants (P), which were translated into English, exemplify the previous ideas:

I will always be proud of my Ecuadorian roots, independently of how I pronounce another language. (P14)

I do not think my Ecuadorian identity is affected by my English pronunciation or my desire to perfect my pronunciation to be similar to a native speaker’s. (P1)

My identity remains the same. The only thing that is expected when learning a new language is obviously to speak like a native speaker, and we do not do it in order to be like them but for the language itself. (P10)

My Ecuadorian identity would not be affected since the characteristics that make me Ecuadorian are still there. Learning a new language and speaking it like a native speaker is a new characteristic or skill that does not make my other characteristics disappear. (P11)

Nevertheless, six students stated that their Ecuadorian identity is affected when trying to pronounce it like a native speaker. They stated that if they lose their Latin accent, other people will not be able to identify where they are from or may think that they want to be like foreign people:

I think it does because the accent gives clues about our ethnicity. So, when we speak English with our Latin accent, we are expressing our cultural diversity. (P58)

Personally, I think people’s accents are part of their culture because they show the speakers’ native tongue. If I lose my Latin accent, people from different nationalities won’t be able to appreciate or identify my nationality, which is very important to me. (P3)

For me, our Latin accent is one of our biggest characteristics, and getting rid of it is getting rid of our identity and what defines us culturally. (P25)

People may think that I am trying to hide my identity and pretend to be a foreign person. (P24)

The analysis of the paragraphs about how speaking like a native speaker will help the preservice teachers in the future (second open-ended question) yielded the following major themes: to get better job opportunities in different professional areas and as EFL teachers, to increase self-confidence at the time of listening and speaking the language, to get a job or study in an English-speaking country, especially the USA, and to be better role models and teachers.

Most participants (n = 60) deem that speaking like a native speaker would give them an edge when looking for a job in general, and of course, as English teachers:

Being able to speak like an English native speaker would help me a lot to find a job in the future since most private schools look for teachers with good pronunciation and good performance when speaking English. It can also help me to increase my confidence in my knowledge and pronunciation of the language. (P12)

Mainly, it would help me improve my professional skills and thus help me work not only as a teacher but also in other areas, for example, as a translator in a company. So, my main objective is to speak like a native speaker. (P21)

More than half of the participants (n = 41) state that having a native-like accent would increase their English communication confidence:

Having a native-like accent allows people to understand better and helps communication to be felt more natural. (P57)

I could communicate with native speakers better and make myself understood easier. (P67)

Less than half of the participants (n = 24) state that having a native-like accent would help them work and study in an English-speaking country:

In a country where there is no future, it is extremely important to get out of here, and a viable option is to travel to a developed country like North America. English is the main language in first-world countries, so speaking this language and passing as a native speaker is a huge advantage in academic and work fields. (P2)

To fulfill my objective of traveling to an English-speaking country, it is important that I can communicate easily and simply with native speakers. (P69)

Lastly, some participants (n = 18) believe that speaking like a native speaker would make them better teachers:

Knowing how to speak like a native speaker means that, among other things, I have the knowledge of the process of producing each sound and of the differences between English and my native language; therefore, I could teach that process to my students and facilitate them the way to reach correct pronunciation, because only making them repeat my pronunciation without knowing about the process behind it is not optimal. (P70)

Speaking like a native speaker would greatly help my future as a teacher because my students would learn from my pronunciation, and if I have bad pronunciation, they won’t learn efficiently. (P28)

Discussion

This study examined EFL preservice teachers’ attitudes toward pronunciation issues (models and targets, identity, and confidence) after taking phonetics and phonology courses. Five attitude dimensions were revealed after factor analysis: Importance of the native-speaker GA accent, Satisfaction with NNS pronunciation, Pronunciation confidence, Native- vs. nonnative-speaker pronunciation teachers, and Interest in the British accent. The first factor, Importance of the native-speaker GA accent, which represents the highest level value on a five-point Likert scale (M = 4.38), entails the significant appraisal that preservice EFL teachers give to the native pronunciation model, especially the GA accent since they think it would help them in their future; therefore, they wish they sounded as native speakers, try to emulate this accent, and consider it as an English learning objective. They also think that teaching pronunciation is important and effective. By and large, research has shown the tendency of EFL teachers and learners to indicate a strong preference for standard native accents-GA or GB (Jenkins, 2007; Timmis, 2002)-and the preservice teachers of this study are not the exception. They stated that having a native accent will give them an advantage when looking for any job, acknowledging the importance of English as a core skill in the globalized world (Graddol, 2006) and when applying for an EFL teaching post, implying that employers prefer to hire English native speakers as teachers (García-Ponce et al., 2020). Many participants also think that a native-like accent would increase their communication confidence since people will be able to understand them better, and so will they.

In addition, since some participants (34%) want to work or study in an English-speaking country (mainly the USA), they think that a native accent will allow them to communicate with native speakers easily, which is in line with the idea that a native-speaker standard model is very appropriate indeed for English learners who aim to communicate with native speakers (Jenkins, 2007; Kirkpatrick, 2006). The participants also stated that having a native-like accent will make them better role models and teachers. Like in Timmis’s (2002) and Uchida and Sugimoto’s (2019) studies, the preservice teachers of this study reckon that NNS teachers should acquire native-like pronunciation; in fact, one of their English learning goals is the achievement of such type of pronunciation. As can be seen, for the preservice teachers, the context for target language use, which should determine pronunciation goals (Jenkins, 2007; Rogerson‐Revell, 2011), is not a decisive factor since most of them would not use the language to communicate with native speakers and still aim at native-like pronunciation.

In the same vein, the second factor, Satisfaction with NNS pronunciation, which represents the lowest level value on the five-point Likert scale (M = 2.57), reflects the preservice teachers’ discontent with their English nonnative pronunciation. This factor encompasses the participants’ desire of not keeping their native accent when speaking English because they are neither happy nor comfortable with it. They believe it is unacceptable for an English teacher to speak with an Ecuadorian accent. Furthermore, part of this factor is the belief that their Ecuadorian identity is not affected when pronouncing English like a native speaker. There is a tendency for teachers in the expanding circle to hold negative views toward their own accented English. For instance, Monfared (2018) reported that English teachers in the outer circle were more confident and happier with their accented English than those in the expanding circle. The outer-circle teachers were more motivated to preserve their nonnative accents, while the expanding-circle teachers wanted to sound like native speakers. However, as stated by Monfared, both groups of teachers seemed to be influenced by the native-speakerism ideology and were more likely to project a native-speaker image to be accepted by students and employers.

According to Brown (2014, p. 160), three considerations can influence pronunciation targets: intelligibility (how easy someone can be understood), image (“trying to convey an impression of being a prestigious speaker of English”), and identity (showing who someone is individually and concerning country and native language). As the results show, intelligibility is not enough for these preservice teachers, and image overrides identity when choosing the pronunciation target; in other words, they are more interested in being “perceived as good confident English speakers” (Brown, 2014, p. 159) than in showing and preserving their Ecuadorian identities, which is confirmed with the significant correlation found between Factor 1 and the variable Importance of reaching a high English proficiency level. The results agree with Georgountzou and Tsantila (2017), who found out that even though Turkish EFL learners highly valued their culture, they also set a high value on native-like English pronunciation, and with Brabcová and Skarnitzl (2018), who noted that most Czech EFL learners did not “feel the need to express their identity through accent” (p. 48). Most participants stated that their desire to perfect and master the English language does not undermine their pride in their Ecuadorian identity.

Nonetheless, L2 learners may face ethical issues when adopting a native-like accent since they may feel that their cultural link with their mother tongue can be weakened (Dalton & Seidlhofer, 2001). Learners who are proud of their nationalities and languages are more likely to speak English with an accent that identifies their mother tongue and country of origin and might be reluctant to imitate a native-speaker accent since they might feel that “this would be tantamount to changing their personality and identity” (Brown, 2014, p. 159). For instance, Pullen (2012) reported that the achievement of native-like English pronunciation was unimportant for EFL learners who were more affiliated with their culture. This can be the case of the six participants who reported that their identity is indeed affected when trying to sound like a native speaker and may feel that changing their pronunciation is synonymous with interfering with their identity (Jenkins, 2007). Nevertheless, most participants do not feel that way, and some even think pronunciation is unrelated to identity. This latter belief can be problematic when teaching pronunciation since not being aware of the relationship between pronunciation and identity can interfere with the understanding that some learners may feel that their identity is threatened and that native-like pronunciation may not be a target for all students. Therefore, preservice teachers must reflect on the varieties of English accents and pronunciation targets that teachers and students aim for so that instruction can be tailored and evaluated accordingly.

The third factor, Pronunciation confidence, shows a medium-high level value on the five-point Likert scale (M = 3.65) and entails the preservice teachers’ feelings of English pronunciation confidence, satisfaction, and competence. It can be said that after taking the Phonetics and Phonology courses, the preservice teachers are not confident in their pronunciation, which could derive from their desire to achieve native-like pronunciation. If this goal encourages them to continue practicing and learning, it can be a positive influence that resonates with the requirement of high-quality teachers, who are lifelong learners, to improve the quality of education (Murray, 2021). However, if it refrains them from their willingness to teach pronunciation and the development of a legitimate English speaker identity, then the target should be reconsidered. As Murphy (2014) argues, many NNS teachers are reluctant to teach pronunciation because they “feel insecure about the quality of their own pronunciation even when such feelings are unwarranted” (p. 205).

On the other hand, NNS teachers tend to hold more positive attitudes toward pronunciation teaching when they have a higher confidence in their pronunciation (Uchida & Sugimoto, 2019). The fact that the Pronunciation confidence factor correlated significantly with the variables Frequency of English usage outside the classroom, Self-evaluation, and Living in an English-speaking country suggests the necessity for EFL teaching programs to include student exchange opportunities in English-speaking countries since, as Uchida and Sugimoto (2019) noted, living in an English-speaking country positively affects pronunciation confidence. In addition, it should be highlighted that two items related to the effort made for improving pronunciation and attaining native-like pronunciation factored with Pronunciation confidence, suggesting that the preservice teachers, by using their knowledge of phonetics and phonology, make an effort to try to sound as native speakers, which might give them confidence.

The fourth factor, Native- vs. nonnative-speaker pronunciation teachers, indicates a medium-high level value on the 5-point Likert scale (M = 3.62) and involves the preservice teachers’ preference for being taught pronunciation by a native-speaker teacher rather than by an NNS counterpart. However, they do believe that NNS teachers can teach pronunciation. This factor also involves the belief that only native-speaker teachers should teach pronunciation. These beliefs concur with the preference for native-like pronunciation models representing accuracy and perfection. In general, teachers and learners consider native-speaker teachers to be better at teaching pronunciation than NNS teachers (Henderson et al., 2015); for instance, even though the students in Li and Zhang’s (2016) study showed significant pronunciation gains after being taught by a NNS teacher and no significant gains when taught by a native-speaker teacher, the students preferred the latter.

Lastly, the fifth factor, Interest in the British accent, reflects a low mean score on the Likert scale (M = 2.66), showing that the participants place little importance on acquiring the British accent. Only the participants who had taken extra English courses (32.9%) and had lived in an English-speaking country (8.6%) showed interest in learning this accent. Nonetheless, this fact also underscores the importance of exchange programs to help preservice teachers adopt a more open position toward other native-speaker models and different NNS models (Murphy, 2014).

It can be said that the knowledge gained in the Phonetics and Phonology courses may have influenced the participants to aim for the attainment of native-like pronunciation and to feel dissatisfied with their nonnative accents; however, more research is needed to determine how their attitudes and future teacher identity develop in those courses. It would be helpful to determine the influence their dissatisfaction with their nonnative pronunciation has on the development of legitimate English-speaker identities. Longitudinal studies can be conducted using interviews to gain a deeper understanding. We hope that the findings of this study contribute valuable insights into pronunciation issues in the realm of EFL teacher education even though, due to the small sample size, the results cannot be generalized.

Conclusions

This study depicted Ecuadorian EFL preservice teachers’ attitudes toward pronunciation issues after taking Phonetics and Phonology courses. The participants’ positive attitudes toward achieving native-like pronunciation suggest that a native-like accent as a pronunciation model for teaching phonetics and phonology suits future EFL teachers’ preferences, needs, and goals. The goal of attaining such pronunciation is directly related to the image they want to project, which is being highly proficient English speakers. Nevertheless, embedding pronunciation issues (such as native and nonnative accents as models and targets, identity, pronunciation confidence, and the like) that prompt reflection and analysis in the curriculum of those courses seems pivotal for preservice EFL teachers. Such insights can help them forge their identities as pronunciation teachers and be more open to different English accents, which in turn will allow them to make conscious decisions when teaching and setting pronunciation learning outcomes.