Introduction

Youngsters are usually portrayed as people with little interest in reading and writing (Borsheim et al., 2008). Nevertheless, on closer inspection, we must acknowledge that young people undertake reading and writing, albeit mediated by technology, which offers them audiovisual platforms where they read and comment in non-traditional ways (Collier, 2007). Hence, as society gradually evolves and cultural products are consumed and produced in different ways and formats, education must adjust to these changes. Otherwise, teachers would be preparing students for the past rather than for the communicative demands of the future. The world-now and in the coming years-needs citizens “who think creatively, innovatively, critically, independently, with the ability to connect” (Ea, 2016, 2:07). Introducing multimodality in secondary education classrooms in general and English as a foreign language (EFL) in particular can well contribute to developing such skills in the students.

Scholars such as Unsworth (2001) see multimodality as essential for the EFL classroom, as students are presented with texts and discourses that combine different modes of expression. Exposing students to (digital) multimodal texts and asking them to produce them seems to be a great way of raising awareness of the different modes students currently have to construct and convey meaning (Norris, 2004). Likewise, students should be allowed to develop their multiliteracies through digitally mediated communication to guarantee their preparation as today’s world literate citizens. Cope and Kalantzis (2009) highlight the significance of equipping students with the skills that will help them become active citizens despite the swift shift in our means of communication. My aim with this paper is to offer a teaching proposal built around a corpus of authentic texts from different modes and media to foster multiliteracy in the EFL classroom. More specifically, this paper seeks to introduce and work on students’ multimodal communicative competence in EFL using the Society Papers written by Lady Whistledown, one of the main characters of Julia Quinn’s novel The Viscount Who Loved Me (2000), a historical romance set in 19th-century England. To do so, I first conducted a lexico-grammatical, discursive, pragmatic, and multimodal analysis of the novel and its subsequent ongoing remediations,1 namely the second season of the series Bridgerton (Dunye, 2022) and posts on Twitter. Then, based on such an analysis, I designed a gamified task-based teaching proposal to develop students’ multiliteracies, 21st-century skills (i.e., communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity), and multimodal awareness. Besides, the selected topic seems to suit Krajcik and Blumenfeld’s (2005) suggestion regarding creating a genuine real-world context where effective learning happens.

Lady Whistledown’s writings are clear instances of the phenomenon of gossip, which is “an important social behaviour that nearly everybody experiences, contributes to, and presumably intuitively understands” (Foster, 2004, p. 78). Students may feel motivated by this psychological strategy since, according to Foster (2004), it is something people often experience either as an active agent or an external one while communicating. Its functions involve informational exchanges, leisure activities, persuasion, and social gatherings. Moreover, the shifting technology triggered in society-namely through microblogging services such as Twitter-seems to place this reporting network as an appropriate way to bring new modes of communication into the EFL classroom. Technology may contribute to developing secondary education students’ multimodal competence and multiliteracies, especially critical thinking and creativity skills. Considering these things, I selected Julia Quinn’s novel and its ensuing remediations-the Netflix series and Twitter profile-as ideal and witty examples. Besides, I decided to use the microblogging service Twitter (which involves several modes such as audio, visual, verbal, and compositional) as the platform for students to share their tasks, develop their digital competence, and reflect on the implications and affordances of this medium.

Lastly, gamification was integrated to maintain student engagement throughout the learning unit. To do so, the teaching proposal starts with a challenge request: uncovering a scandal. Hence, the lessons will become an escape room where students receive clues as rewards for adequately fulfilling their tasks. This way, at the end of the unit, each group of four students will have personified an imaginary Lady Whistledown’s disciple. They will have analysed and produced multiple remediated texts based on the corpus. The learning unit’s ultimate goal-and task-concerns uncovering the season’s most damning scandal. Hence, students must generate an original digital text imitating Lady Whistledown’s speech yet adjust it to the 21st century. Such multimodal text is based on the rewards gained throughout the unit. According to Moura and Lourido-Santos (2019), gamification can be a successful strategy to enhance the learning and teaching process since the game progression is directly linked to the students’ need to make choices and formulate hypotheses, which help expand fundamental skills.

Theoretical Framework

Multimodality in the Classroom

Nowadays, communication has become more multimodal due to the emergence of technology. Adami (2017) describes multimodality as a communicative phenomenon that merges semiotic modes. Conventionally, the written text was thought to be the chief manner of producing knowledge. Nonetheless, the current orchestration of embodied and disembodied modes unleashes new text varieties (Kress, 2010) that may be worth using in the EFL classroom. Jewitt (2008), van Leeuwen (2011), and Sewell and Denton (2011) also stress the importance of intertwining modes by giving equal relevance to writing language, typography, colours, sounds, images, and gestures.

Students must be exposed to multimodal input and pushed to produce multimodal output in the EFL classroom (Diamantopoulou & Ørevik, 2021). However, teachers must avoid taking students’ proficiency in multimodality for granted (Sewell & Denton, 2011). It cannot be denied that we are continually being bombarded by multimodal input in our daily lives. Nevertheless, students must be given the essential tools to understand and discern the implications hidden in the received multimodal messages (Doering et al., 2007). Additionally, as students can be active learners and producers of digital multimodal texts, teachers must prepare them to do it properly. This may be attained by enhancing their multimodal communicative competence in their L1 and English.

Doering et al. (2007) also claim that when it comes to (digital) multimodal communication, the composing plan entails what people crave to say and how it is said. Thus, students must become aware of “how to go beyond simply creating [digital] multimodal texts” to manage to produce them by “using visual rhetoric to effectively attract, engage, and influence their audiences” (p. 41). The proposal presented here has been precisely planned and designed to promote the use of multimodal authentic texts in the EFL classroom.

Communicative Language Teaching and Task-Based Learning

Many English teachers have conservatively prioritised the presentation-practice-production teaching method. Nonetheless, according to Richards and Rodgers (2000), communicative language teaching (CLT) should be considered a potential alternative. This functional approach seeks to reinforce the overriding significance of the communication process within the EFL classroom (Richards & Rodgers, 2000) and aims to demonstrate the usefulness of learning by doing. Thus, topics must be aligned with the students’ interests (Dörnyei, 1994). Likewise, the focus on form, which is task-dependent, should be taught inductively. Although students’ fluency is to be prioritised when using English, accuracy must also be targeted, as errors are essential to the learning process. When implementing this approach, the teacher becomes a facilitator instead of a lecturer, and meaningful communication is promoted in small group interactions (Richards & Rodgers, 2000; Van Avermaet et al., 2006).

As Ellis (2003) indicated, tasks are a crucial element in CLT since their accomplishment presses demands on students to succeed in getting their message through. Similarly, Richards (2013) defines tasks as the features that trigger language learning. Tasks entail meaningful interactions because they mainly focus on conveying meaning in simulated communicative situations that integrate the four linguistic skills and engage cognitive processes. Besides, there must be a clear non-linguistic outcome (Ellis, 2003).

To guide the design of a teaching proposal based on the CLT approach, Willis (1996) established a framework: pre-tasks to introduce the topic and activate previous schemata, tasks, and post-tasks to reflect on the learning process and the final product and develop students’ learning-by-doing competence and metacognition. The task-based learning (TBL) approach allows each student to move “from passive to active, from recipient to participant, from customer to citizen” (Livingstone, 2004, p. 20). Students can be involved in real-world contexts by completing tasks and going through task cycles. Hence, they will inductively learn how to express meaning, attend to form, and be offered the opportunity to develop fluency while communicating and collaborating (Willis & Willis, 2007).

Gamification

Sparking students’ motivation towards learning is important, yet maintaining this engagement through an extensive period can be far more challenging, especially in secondary education. Gamification may be chosen as an appropriate manner to attain an effective learning process in the teaching context. According to Kapp (2012), gamification is a way to “motivate action and promote learning” (p. 10), the effectiveness of which has been demonstrated in several papers.

Kapp (2012) highlights the significance of storytelling and choosing an avatar when applying gamification principles. This provides the students with context and fosters personal involvement in the situation. Introducing challenges for the students to solve can be an effective strategy to facilitate the process. Challenges imitate the “call to adventure” described by Campbell (1949) following the Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction model2 since “the simple introduction of a goal adds purpose, focus, and measurable outcomes” (Kapp, 2012, p. 28). By doing so, the three main components that make a game engaging-curiosity, challenge, and fantasy-are attained. Simultaneously, minimally penalising failure and providing students with awards instead of numeric marks enhance students’ excitement and willingness to participate and satisfy their curiosity (Dörnyei, 1994). Hence, extrinsic and intrinsic motivation are combined. Lastly, experts also highlight the significance of healthily involving conflict, cooperation, and competition through gamification to develop interpersonal competence (Kapp, 2012). This may be particularly profitable in secondary education, where competencies such as leadership, teamwork, active listening, responsibility, verbal and non-verbal communication, and negotiation-among many others-are key.

Multiliteracies and 21st-Century Skills

Formerly, being able to write and read printed texts meant being literate. However, O’Rourke (2005) underscored the current saliency of multiliteracies motivated by the demands of the 21st century. This occurred due to the rise and expansion of technology and the ensuing new modes and media of communication. In fact, according to the New London Group (1996), multiliteracies reinforce former pedagogies because they focus on “the multiplicity of communications channels and media, and the increasing saliency of cultural and linguistic diversity” (p. 64). Bruce (1997) highlighted teachers’ concerns about whether technology may dissent or replace conventional reading and writing skills. Nowadays, the debate has been overcome since there is general agreement on the importance of becoming a multiliterate person to participate fully in today’s society. A multiliterate person refers to someone who is:

flexible and strategic and can understand and use literacy and literate practices with a range of texts and technologies; in socially responsible ways; in a socially, culturally, and linguistically diverse world; and to fully participate in life as an active and informed citizen. (Borsheim et al., 2008, p. 87)

To attain multiliteracy, the KSVA3 model (Binkley et al., 2012) groups ten needed skills of the multiliterate 21st-century citizens into four categories: ways of thinking, ways of working, tools for working, and living in the world. The first comprises creativity and innovations, critical thinking, problem-solving and decision-making, and learning to learn and metacognition. The second category involves communication and collaboration. The third one includes information and literacy in information and communications technology, and the fourth encompasses citizenship, local and global knowledge, life and career, and personal and social responsibility. However, these categories seem to go further to give more prominence to creativity and critical thinking skills.

Even though the ten skills are highly significant nowadays, four are catalogued as outstanding; they are the 4 Cs: communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity. Their development may have a massive impact on students’ success when coping with the demands of the current professional world (Thornhill-Miller et al., 2023). It should also be developed in the EFL (secondary education) classroom.

Method

Context and Participants

The designed learning unit is entitled What a Scandal!, and it integrates 16 lessons of 55 minutes each (see Appendix for a lesson sample). This unit aims to introduce multimodal ensembles in the secondary education EFL classroom to develop students’ multiliteracies and 21st-century skills. To create this teaching proposal, I compiled a corpus of authentic texts around Lady Whistledown’s Society Papers published in Julia Quinn’s novel The Viscount Who Loved Me (2000). Brief opening sections illustrate Lady Whistledown’s gossip columns published for her contemporaries. They provide the readers with a brief context for each chapter. The corpus also included the novel’s subsequent remediations, namely Lady Whistledown’s appearances as narrator in the second season of the Netflix series Bridgerton (2022). Additionally, tweets posted between the 8th of February 2021 and the 28th of March 2022 on the Twitter account @Bridgerton (https://n9.cl/eifza) were gathered. Both remediated texts were manually compiled from the official Netflix platform and Twitter account.

The resulting teaching proposal is meant to be implemented in a Spanish school, and it was designed for students in the fourth year of secondary education (equivalent to the 10th grade in other contexts). This year of compulsory education consists of four weekly sessions of 55 minutes. This means that the learning unit could be implemented in one school month.

Corpus Compilation

I collected a corpus for analysis and to be able to base my proposal on authentic material following these criteria:

Are the texts ongoing and authentic?

Is the topic meaningful and potentially engaging?

Are the texts exploitable and feasible?

Firstly, I compiled a corpus considering Lady Whistledown’s columns from the novel, part of a saga published between 2000 and 2006. Nonetheless, the second book seemed to be the most fitting alternative since its Netflix remediation was aired on the 25th of March 2022. Hence, I manually transcribed and collected Lady Whistledown’s appearances as narrator in the second season of the Netflix hit Bridgerton. Equally, as I meant to have several authentic materials to be brought into the classroom, tweets posted between the 8th of February 2021 and the 28th of March 2022 were extracted. To do so, I took screenshots and copied the links to the tweets. I aimed to select an appealing and culturally relevant corpus. Hence, thanks to characters such as Kate and Eloise, this story allowed me to deal with sociocultural aspects and Sustainable Development Goal4 number 5 (gender equality) in an original and motivating manner. Finally, Lady Whistledown’s discourse exhibits a vast richness. The Netflix series may be deemed an accurate source because it implies distinct audiovisual materials, topics, and digital features to be brought into the EFL classroom. Similarly, not having read or watched the first book or season does not affect the comprehension of this sequel, which makes my proposal’s development rather feasible.

Tools for the Analysis

As the theoretical framework shows, my main aim was to design an original and engaging teaching proposal following CLT and TBL principles in which students innovatively face authentic multimodal remediated texts from a receptive and productive point of view. To do so, I considered multimodality and Sustainable Development Goal number 5: gender equality. While working on it, students will develop their 21st-century skills and multiliteracies.

Once the teaching proposal was planned and designed, I evaluated how it aligned with the intended theoretical and methodological principles presented in the Literature Review section. Thus, I created a checklist (see Table 1) to evaluate this and other proposals that could be designed following similar principles.

Table 1 Checklist for the Analysis of the Teaching Proposal

| Multimodality | 1. Is the selected topic original and potentially engaging for teenagers (e.g., relevant or in line with their interests)? |

| 2. Does the corpus contain authentic multimodal original and remediated texts/ensembles from various sources? | |

| Remediation | 3. Does this teaching proposal deal with original and remediated texts from different media? |

| Multiliteracies, Sustainable Development Goals, and 21st-century skills | 4. Does this teaching proposal develop students’ multiliteracies? |

| 5. Does this teaching proposal develop any Sustainable Development Goals? | |

| 6. Does this teaching proposal develop students’ 21st-century skills? | |

| Communicative language teaching and task-based learning | 7. Does this teaching proposal follow the principles of the communicative approach? |

| 8. Does this teaching proposal follow the task-based learning approach? | |

| 9. Are the aims of the pre-tasks, tasks, and post-tasks clearly defined? | |

| 10. Are the tasks meaningful and purposeful? | |

| 11. Are the tasks suggested adequate for the stage? | |

| Practical aspects | 12. Are the steps and instructions of the teaching proposal coherent and understandable? |

| 13. Is this teaching proposal in line with the assessment criteria? | |

| 14. Overall, is the teaching proposal innovative? | |

| 15. Is the teaching proposal feasible and exploitable for the EFL classroom? | |

| Gamification | 16. Is the aim of the gamified teaching proposal to engage action and encourage learning while solving problems? |

| 17. Does the teaching proposal provide a meaningful context for the presentation of tasks? |

The Teaching Proposal: What a Scandal!

This section will first show a description of the designed teaching proposal. Then, its evaluation will be presented.

Description of the Teaching Proposal

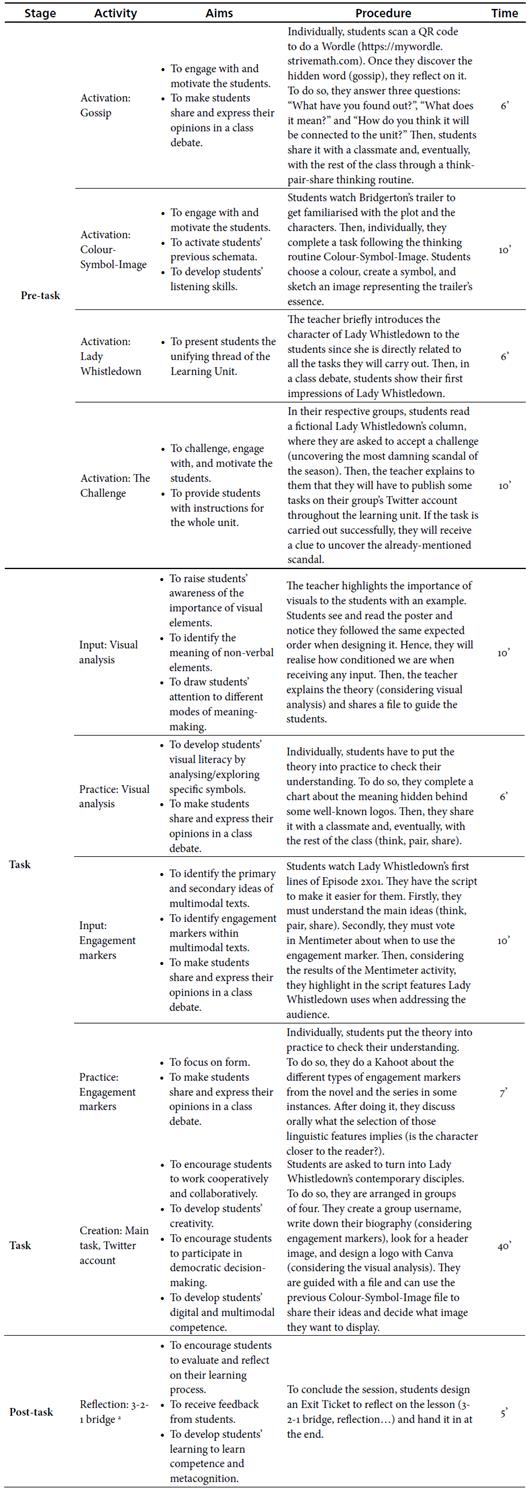

As explained above, the designed learning unit consists of four weekly sessions of 55 minutes and is oriented towards 15 to 16-year-old Spanish students from the fourth year of secondary education (10th grade). The unit revolves around a mystery set in the Regency era that must be solved. Lady Whistledown will send students a letter requiring their audacity to uncover the most damning scandal of the season. Students must complete diverse tasks leading them to seven clues they must interpret correctly. The 16 lessons of the unit follow the sequence of activation, input, practice, creation, and reflection (see Figure 1). Each “creation task” (eight) will be part of the summative assessment defining each student’s final mark.

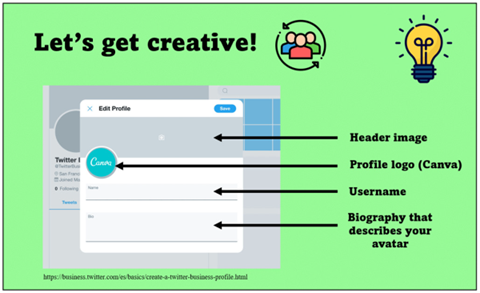

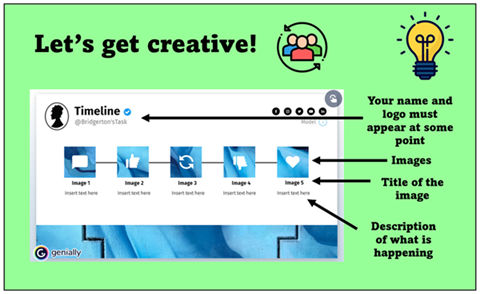

First, students will have to form groups of four. Each team will personify an imaginary Lady Whistledown’s disciple. Hence, creativity and inventiveness will already be fostered in the first two lessons, when students will be asked to invent an avatar representing them as a team and give it a name, a personality, and an image. Each team must also design a corporate Twitter profile according to their avatar. There, their tasks will be posted, and mutual feedback will be given to and received by the rest of the groups. To design each Twitter profile, scaffolding will be provided, such as the example in Figure 2, in which the structure of a Twitter profile is shown to support students’ production/completion of the task.

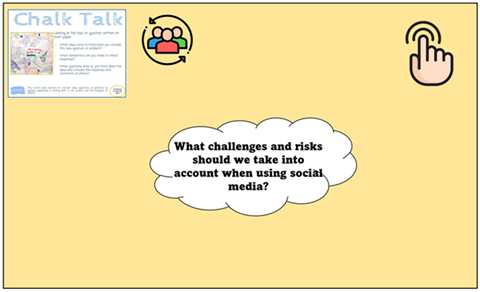

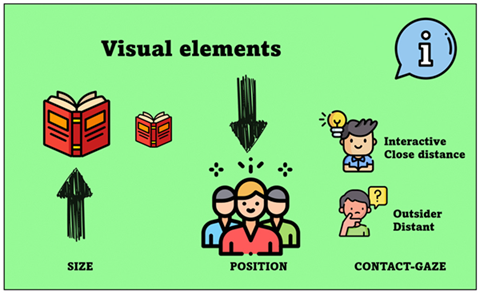

Next, the students will gradually work on Lady Whistledown’s idiosyncratic use of the verbal mode. The aim is that, at the end of the unit, the students will be able to produce their gossip column, just as the character does. However, since Lady Whistledown belongs to the Regency era, students must adjust their writings to their century and share them on Twitter without losing the original tone. To help them do it, they will be instructed to focus on visual analysis, engagement markers, evaluative language, specific jargon, syntax, figurative language, politeness, implicatures, and Twitter affordances, among many other features. Using materials that attempt to simulate the Regency era, the student’s cultural awareness and expression competence may be developed when working with the three media brought into the classroom. This topic also allows students to focus and reflect on social and civic issues related to gender (in)equality and the responsible use of social media. The idea of working on the risks and rules of social media is also intertwined with digital competence. Notably, being competent digitally means using these platforms adequately and ethically to become excellent digital citizens (see Figure 3).

Two of the major strengths of this teaching proposal are the originality and richness of the genres on which it is based. In this case, students will be approaching a social behaviour they may have experienced, which will provide them with a sense of familiarity. Simultaneously, they will be using authentic original and remediated materials from three diverse media that may strike them as motivating-a novel, a Netflix series, and Twitter posts-while opening a range of possibilities to successfully learn how to communicate in English. These materials allow the teacher to bring rich multimodal input into the classroom. Students will receive and produce the sort of input and output typically found in the current digital and multimodal world in which they live, such as posters, memes, or clips, among many others. Figure 4 shows an example of a task where students must analyse three promotional posters designed by Netflix and recreate memes about Bridgerton.

The final task will involve sharing the scandal uncovered by the students after discerning the clues in their gossip Twitter column. To prepare students for this, they will first collaboratively carry out Venn diagrams comparing Lady Whistledown’s use of the verbal mode in the novel, the series, and the Twitter profile, as well as the timelines, voice recordings, Twitter threats, memes, class debates, among others. By doing so, the students will be able to integrate not only the new contents of each lesson but also the ones already targeted in the previous ones. Hence, at the end of the unit, they will have become genuine Lady Whistledown’s disciples. As a final reward, they will be given a congratulatory letter and a certificate (see Figure 5).

To assess students, appropriate assessment criteria are proposed whose aim is to intertwine self and peer assessment while focusing on both the process and the final product thanks to the design of a formative and summative assessment tool. The reason is to avoid judging just one final product that may be affected by many non-educational factors like emotions or context. Table 2 includes the items to be assessed and the corresponding marking criteria. Each task will be evaluated following either a checklist or a rubric.

Table 2 Task and Marking Criteria (Own Elaboration)

| Item to be assessed | Marking percentage |

|---|---|

|

|

10% |

|

|

10% |

|

|

10% |

|

|

10% |

|

|

10% |

|

|

10% |

|

|

10% |

|

|

20% |

|

|

10% |

Note: TAG = Tell a thing you liked, Ask a question, and Give a suggestion

After the completion of each main task, students will be provided with the following marking criteria:

Exceeds expectations (EE): Students show an excellent deep understanding, reflection, and command of the lesson’s contents.

Meets expectations (ME): Students adequately understand, reflect, and command the lesson’s contents.

Needs improvement (NI): Students lack understanding, reflection, and command of the lesson’s contents. The main goals have not been achieved.

If students obtain an NI in any of the first seven tasks, they can submit a new version to compensate for the previous mark and get the corresponding clue. Regarding the two last items (Task 8 and Interest and participation), the students will not have room for improvement.

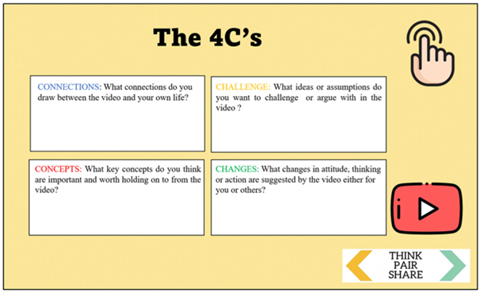

Evaluation of the Teaching Proposal

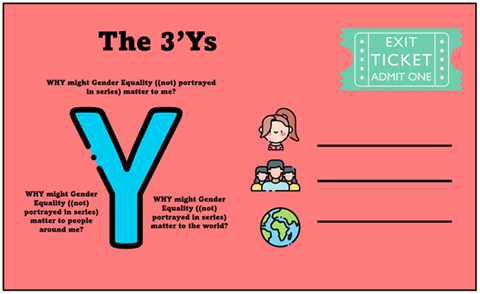

This teaching proposal aims to develop students’ multiliteracies by encouraging them to absorb and produce multimodal content related to diverse media. In addition, it attempts to integrate and work on 21st-century skills-particularly the so-called four Cs (critical thinking, creative thinking, communicating, and collaborating)-when working in groups to critically reflect on the features and matters presented in each lesson to display their thoughts on resourceful and imaginative digital multimodal products. The teaching proposal intends to improve students’ verbal communicative competence by working on the command of lexis and grammar during debates, group discussions, or reception and production tasks such as Twitter posts. Likewise, students are expected to develop their sense of initiative and entrepreneurship and learning-to-learn competencies. This may be achieved thanks to, for instance, tasks that involve students planning and executing a task autonomously to reflect on the importance of the matters developed (e.g., reflecting on sociocultural aspects like gender inequality) or to carry out self and peer evaluation. This is commonly done through thinking routines (such as the 3-2-1 bridge, traffic light reflection, or the 3Ys; see Figure 6),5 which can be included in a post-task phase.

The student’s critical thinking and learning-to-learn competencies can also be developed using feedback techniques. As a scaffolding, students will be asked to follow routines such as the two stars and a wish (see Figure 7), the glow and grow, and the TAG ones. The routines will be accomplished by reading the products the rest of the teams share to learn from them and contribute to other teams’ learning process by displaying the positive and negative features encountered. The students will also have to evaluate their learning process and self-evaluate themselves. These techniques are proposed for the post-task stage. By doing so, students may develop their communicative competence and critical thinking skills as they are asked to reflect not only on their process but also on their final product.

Furthermore, students can also develop their multiliteracies by working on digital tools and platforms to receive and produce content dutifully, creatively, and autonomously through platforms such as Twitter (or Padlet6), Genial.ly (see Figure 8), Canva, Vocaroo, Socrative, Google Forms, AnswerGraden, Mentimeter, or Kahoot. Whereas the first four platforms are managed by students and used to complete some tasks, the last five are designed by the teacher and used in a receptive manner.

Additionally, most tasks in the learning unit are meant to be completed in groups while the teacher guides and facilitates learning. Therefore, the autonomous and cooperative learning style encouraged will presumably allow students to exchange ideas and strategies, easing, in this way, the process of activating previous schemata and connecting it with new knowledge, as learning theories highlight the importance of making such connections and stress meaningfulness.

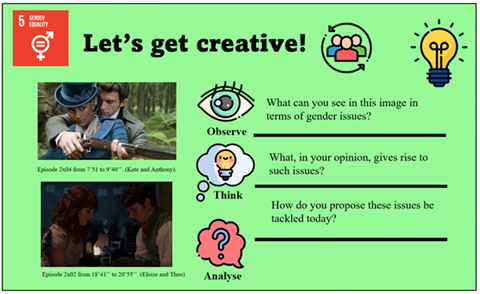

Regarding the Sustainable Development Goals, Lessons 9 and 10 can be devoted to goal 5: gender equality. The students can deal with gender stereotypes, inequality, and microaggressions (such as those in episodes 2x02 and 2x04 of the Netflix series). To do so, some scenes of the series can be shown for students to analyse, reflect on, and denounce situations of gender inequality (see Figure 9). Besides, students must compare such behaviours to their current society to find parallels and divergences among the epochs.

Simultaneously, emotional intelligence also figures prominently when analysing Lady Whistledown’s self-righteousness because students can develop their empathy by focusing on the effect her words may have on the feelings of others. It seems to have great relevance, considering that these are adolescent students.

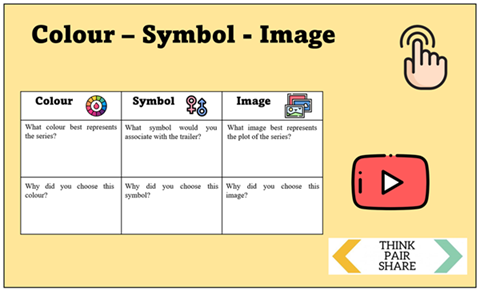

The students’ active learning is fostered through completing tasks where they are active agents instead of passive ones (as has traditionally been the case). Instances of this are tasks that involve think-pair-share strategies, peer or group evaluations, or group discussions, among others. Figure 10, for instance, shows how students must work collaboratively to provide reasons for the selection, prominence, and implicitness of visual features regarding logos.

Figure 10 Example of a Pre-Task Where Students Follow the Think-Pair-Share Strategy (Own Elaboration)

Likewise, in this learning unit, students will have to analyse real-life situations, solve problems, and discover inductively how language is used (see, for instance, Figure 11, where students are required to deal with the jargon employed by Lady Whistledown). The students are further asked to create tweets of diverse purposes and include different media, like timelines, recorders, multimodal narrations, and memes (see Figure 12), rather than just applying the teachers’ theoretical explications.

As regards the exploitability and feasibility of the teaching proposal, there may be some foreseeable difficulty for students when implementing it (e.g., being asked to focus on pragmatic features or to learn about specific affordances). Some texts might also be challenging due to their inner characteristics, such as the ones related to figurative language or the culture of the meme and visual analysis. Nevertheless, these issues may be solved with scaffolding techniques aligned with the learning goals that will guide students through the process (see Figure 13). Those techniques are visual aids like charts, models, adapted thinking routines to activate previous schemata and check understanding, or think-pair-share techniques to promote participation and repeat information if needed. Besides, students can use context to infer meaning.

Following Kapp (2012), failure is minimally penalised, allowing students to satisfy their curiosity fearlessly. To conclude the unit, students will have to interpret all the clues collected (see Figure 14 for a sample clue) through the 16 lessons to solve the mystery of what was stolen and who did it. Students will have to complete one last task where they will completely imitate Lady Whistledown’s verbal mode. They will have to publish the resolution of the mystery as the most damning scandal of the season.

Through the completion of many diverse tasks, the teaching proposal aims to develop students’ competence, multiliteracies, and 21st-century skills and prepare them in a dynamic and positive environment to communicate multimodally in English in the digital world they are and will be immersed in.

Conclusions

Nowadays, students are constantly consuming different sorts of audiovisual communication due to the pervasiveness of social media. Hence, teaching them how these interactions operate seems to be an excellent manner of preparing them to be more proficient and effective in multimodal (digital) communication. Additionally, introducing a contemporary and different topic, such as the Bridgerton saga, in a gamified manner in the EFL classroom may break the monotony. Furthermore, making students discuss the parallels and divergences between the original novel and its current remediations may enhance their cultural knowledge and communicative skills. Diamantopoulou and Ørevik (2021) precisely claim that bringing resources related to pop culture, like TV series or social media interactions, “can be used as compelling sources of cultural and subversive topics” (p. 10) to ponder social values.

Therefore, the teaching proposal presented here may activate students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation while contributing to developing their communicative multimodal competence, their multiliteracies, and their 21st-century skills, namely, critical thinking and creativity. Karatza (2022) stresses the significance of multimodal analysis when developing students’ critical thinking in the classroom. Moreover, the students’ digital competence will also be developed, making them aware of the significance of being effective digital citizens and preparing them for the demands of their society.

Furthermore, during the learning process, the students can reflect on Sustainable Development Goal number 5, which can be easily integrated into the EFL classroom, an excellent challenge for schools, especially for secondary education students. The aim is to make them aware of microaggressions, or what is known as benevolent sexism, and gender inequalities in order to be able to halt them when detected. It is also worth mentioning that EFL teachers need to be trained in multimodal and digitally mediated communication to integrate these concepts in the classroom. In other words, this teaching proposal may be equally beneficial to students and teachers.

To conclude, I do not want to make the error of presenting this teaching proposal as a utopic one that may indeed be successful. I know the differences that educational contexts and even groups in the same school may offer, especially regarding their level and specific needs. However, I also consider that providing students with diverse kinds of scaffolding techniques may bring a response to all the extra difficulties they might face. Hence, this proposal may engage students to work in a gamified, cooperative, alternative, and original manner in the EFL classroom.