Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Ecos de Economía

Print version ISSN 1657-4206

ecos.econ. vol.18 no.39 Medellín July/Dec. 2014

ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN

ECAES, SaberPro, and the History of Economic Thought at EAFIT*

ECAES, SABER PRO y la historia del pensamiento economico en EAFIT

Stephen Meardon*

* Department of Economics, Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Me., USA. [smeardon@bowdoin.edu].

Recibido: 08/17/2014 Aprobado: 11/11/2014

Abstract:

The present article studies the implications of the exam's redesign for exam performances by students at the Universidad EAFIT. Its particular focus is the adequacy of the history-of-economic-thought (h.e.t.) part of the EAFIT economics curriculum as preparation for the Economic Analysis modules of the former ECAES and present SaberPro exams, and for other academic purposes. The sources of information for the article include conversations and correspondence with the academic and administrative leadership of the EAFIT Escuela de Economía y Finanzas and Departmento de Economía, also include h.e.t. course syllabi from the Universidad EAFIT and, by way of comparison, from the Universidad de los Andes, the Universidad de Antioquia, and elsewhere; documents regarding the objectives and format of the ECAES economics exam obtained from the ICFES and AFADECO websites; data for exam results over the period 2006 to 2009 obtained from ICFES.

Key Words: history-of-economic-thought; Economic Analysis; Universidad EAFIT

JEL Classification: B00; B40; A22;

Resumen:

El presente artículo estudia las implicaciones del rediseño del examen Ecaes (Saber Pro) para la presentación por parte de estudiantes de la Universidad EAFIT. Su enfoque particular es la manera como se adecua el plan de estudios en el área de historia del pensamiento económico como preparación para los módulos de Análisis Económico de los antiguos ECAES, hoy SaberPro, y para otros fines académicos. Las fuentes de información para el artículo incluyen conversaciones y correspondencias con los directores académicos y administrativos de la Escuela de Economía y Finanzas y del departamento de Economía de la Universidad EAFIT, tambien se revisaron los planes de estudios de Economía de la Universidad EAFIT, Universidad de los Andes, Universidad de Antioquia entre otras y los datos de los resultados del examen durante el periodo 2006-2009 obtenidos del ICFES.

Palabras clave: Historia del pensamiento económico; Análisis Económico; Universidad EAFIT

Introduction

In 2012, the Instituto Colombiano para la Evaluación de la Educación (ICFES) introduced a new structure for the compulsory exam administered to bachellor's-degree students in their final year. The exam was formerly called the Examen de Calidad de la Educación Superior, or ''ECAES.'' Under that name it included a module for ''Economic Analysis'' comprising 220 multiple-choice questions in a handful of core areas of economics: macroeconomics, microeconomics, statistics and econometrics, and economic thought and economic history (supplemented by reading comprehension and English).1 Now renamed ''SaberPro,'' the exam still includes an Economic Analysis module comprising multiple-choice questions, but their number is reduced to 40. What is more, the questions are redesigned with the aim of testing not so much students' ''knowledge'' in the core areas of economics as their ''competencies'' as economists.

The present report studies the implications of the exam's redesign for exam performances by students at the Universidad EAFIT. Its particular focus is the adequacy of the history-of-economic-thought (h.e.t.) part of the EAFIT economics curriculum as preparation for the Economic Analysis modules of the former ECAES and present SaberPro exams, and for other academic purposes.

The sources of information for the report include conversations and correspondence with the academic and administrative leadership of the EAFIT Escuela de Economía y Finanzas and Departmento de Economía, namely, Juan Felipe Mejía Mejía (Decano), Alejandro Torres García (Jefe del Departamento de Economía), and Catalina Gómez Toro (Jefe de Carrera, Pregrado en Economía); with the faculty members who teach h.e.t. at EAFIT, Mauricio Andrés Ramírez and Luís Guillermo Vélez, and with historians of economic thought outside of the EAFIT who have cooperated with ICFES in the revision of the exam, namely, Jimena Hurtado of the Universidad de los Andes and Alexander Tobón of the Universidad de Antioquia. The sources also include h.e.t. course syllabi from the Universidad EAFIT and, by way of comparison, from the Universidad de los Andes, the Universidad de Antioquia, and elsewhere; documents regarding the objectives and format of the ECAES economics exam obtained from the ICFES and AFADECO websites; data for exam results over the period 2006 to 2009 obtained from ICFES; and notes from a conference with EAFIT economics students about the exam, organized by Catalina Gómez, held on March 27, 2014, and attended by Gómez herself, Alejandro Torres, Mauricio Ramírez, and students Joaquín Andrés Urrego Garcia, Mateo Castro Uribe, and Juanita Gómez Loaiza, as well as myself.

The report has five parts. Part 1 describes the ECAES Economic Analysis module before the redesign, with attention to the relevance of h.e.t. to the exam questions. Part 2 analyzes the results of the exam across Colombian universities, especially the EAFIT and selected peer institutions, over the period 2006-2009. Part 3 describes the redesigned exam post-2012. Part 4 considers the suitability of the course offerings in h.e.t. at EAFIT and its peer institutions, both for students' preparation for the ECAES and for broader pedagogical purposes. Part 5 concludes.

1. The Old ECAES

Understanding the redesign of the Economic Analysis module of the ECAES requires some examination of the ''old,'' pre-2012 module. Such an examination confronts problems of data availability and comparability over the old module's run of years from 2004 to 2011. For instance, only in 2009 did the ECAES become obligatory; the imperfect comparability of results between the two sets of years appears to be one reason for the ICFES's making the Economic Analysis module data available for all universities only for 2004-2009.2 In any case, I will draw from various sources of information to describe the test before the 2012 redesign – with the caveat that while the information for any one year offers a pretty good impression of the test over the entire period 2004-2011, in any other year the test may have differed in small details.

Nevertheless the ICFES Guías de Orientación for the Economic Analysis module show much continuity, and little change, in the stated aim and contents of the exam over period preceding the redesign.3

In 2009, as in 2004, the competencies were interpretive (meaning, ''comprender objetivamente el contenido de un texto, o avanzar en un proceso de reconstrucción psicológica por parte del lector-estudiante de la intención original del autor) argumentative (''la capacidad de fundamentar ... de un problema o fenómeno dado; razonar una determinada hipótesis, proposición o tesis con suficiencia y consistencia'') and propositive (''superar el pensamiento o la actitud crítica y establecer alternativas u opciones de selección, señalar heurísticos para solucionar un problema dado y comprometer su ser en la definición de una dirección'') (Guía 2004, p. 21; 2009, p. 20)

In 2009, as in 2004, the exam purported to test those competencies with 220 multiple-choice questions in the core areas of macroeconomics, microeconomics, statistics and econometrics, and economic thought and economic history, plus reading or language comprehension. The students answered the questions in two exam sessions of four hours each separated by a two-hour break (2004, p. 22; 2009, p. 20). The distribution of questions over the core areas changed somewhat over the years: macroeconomics and microeconomics were devoted 48 questions each in 2009, down from 60 in 2004; statistics and econometrics, 32, down from 40; economic thought and economic history, 32, down likewise from 40; and reading comprehension, 15, down from 20. The reductions made way for a new area of examination within the module, namely, English, comprising 45 questions in 2009. But the nature of the questions in each area remained the same.

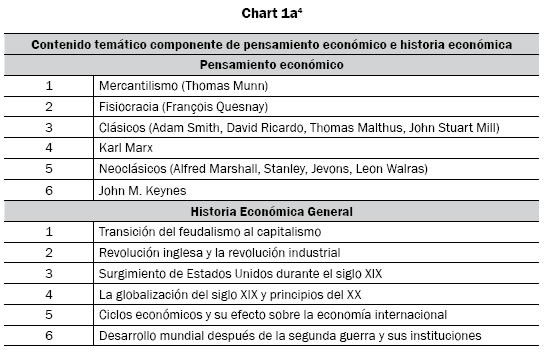

In 2009, as in 2004, each of the core areas of the Economic Analysis module was broken down into several finer ''thematic components.'' The components changed little – in most areas, not at all. The components of macroeconomics in 2009, for instance, just as in 2004, were economic measurement, aggregate supply, aggregate demand in the short and long runs, theory of consumption, theory of investment, closed-economy macro in the short and long runs, open-economy macro in the short and long runs, economic growth, inflation and unemployment, fiscal theory and policy, monetary theory and policy, and exchange-rate theory and policy. Likewise, and more relevant to this report, the core areas of economic thought and economic history were broken down in 2009 as follows in Charts 1a and 1b:

While the economic history thematic components changed modestly from 2004 to 2009, the economic thought components did not.

In respect to economic thought the Guía offered additional indications about the nature of the questions. The indications changed little between 2004 and 2009. First, the Guía suggested a ''bibliografía'' to help students prepare for the questions. In 2004 it included incomplete references to popular textbook treatments of the history of economic thought by Eric Roll (1939 and later eds.) and Harry Landreth and David Colander (1994 and later eds.), both widely read outside of Colombia and translated to Spanish, together with the home-grown text by Homero Cuevas (2001 and later eds.). In 2009, the Guía still cited Landreth and Colander but replaced Roll's and Cuevas's texts with Ernesto Screpanti and Stefano Zamagni's Panorama de la Historia del Pensamiento Económico (México: Compañía Editorial Continental, 2000) (Guía 2004, p. 28; 2009, p. 27).

Second, the Guía offered a number of sample questions, including questions of economic thought. The sample questions, mirroring those on the exam, were of two types: some had a unique correct answer, some two correct answers. Among the sample questions for both 2004 and 2009 was the following on Marx:

8. Marx coincide con los economistas clásicos en que la obtención de la ganancia es la razón de ser de los capitalistas. Sin embargo, su enfoque es diferente. El concepto de ganancia en Marx considera que A. es la fuente de reproducción de la fuerza de trabajo B. responde a la utilidad marginal del capital C. es la forma transfigurada de la plusvalía D. se regula enteramente por el valor del capital empleado

Clave: C Componente: pensamiento e historia Competencia: interpretativa5

The question is notable for a few characteristics:

- It is written expressly to cover the h.e.t. and history ''componente'' of economic analysis.

- As signaled by its carrying the tag of the ''interpretive'' competency, it tests the student's recollection of the definition and function of an important concept in Marx's system of thought.

- A reasonable strategy for answering a question like this one correctly, therefore, would be to study one of the Guía's recommended h.e.t. textbooks and commit to memory, in summary form, the main ideas of the six principal thinkers or schools enumerated for the ''thematic content'' of the h.e.t. component.

The Guía anticipates and argues against the latter point:

No obstante, la evaluación de este componente no puede ser de carácter memorístico. Ella debe recurrir a la evaluación de las competencias del estudiante examinando su capacidad para contextualizar fases críticas de la historia económica nacional e internacional, enmarcando los problemas y aspectos económicos que las caracterizaron. (Guía 2004, p. 19; 2009, p. 18)

But the ''no obstante'' remark is telling, and the argument is only partly convincing. While the question does test the student's ability to identify the ''problems and economic aspects'' of Marx's thought, such identification could indeed be done effectively by memorization of facts. For students whose knowledge of h.e.t. is drawn from the recommended textbooks, rote memorization is the most likely way to do it.

Also among the sample questions for both 2004 and 2009 was the following on Keynes:

11. El pensamiento de Keynes se caracterizó por estudiar las causas de las crisis económicas condicionado por el contexto socio–histórico en que vivió. Para contrarrestar la crisis de los años 1930 según Keynes, se debía fomentar

1. una política monetaria expansiva para solucionar el problema de liquidez. 2. el gasto público para estimular el crecimiento en la inversión. 3. unas políticas económicas para estimular el crecimiento de la demanda agregada capaz de crear nuevas inversiones. 4. un cambio en la propensión marginal a consumir mediante la reducción de los precios.

Clave: B (2 y 3) Componente: Pensamiento e historia Competencia: Argumentativa6

Here, again, the question is written expressly to cover the h.e.t. and history ''componente'' of economic analysis. But in this question, as signaled by the tag of the ''argumentative'' competency – and unlike the Marx question – each answer contains a theoretical proposition. In addition to recalling certain facts about Keynes, the student is prodded to work through the rationale of the theoretical proposition. Did Keynes propose an expansionary monetary policy under the circumstances cited, and did he expect such a policy to solve ''the problem of liquidity''? Did he propose public spending, and did he expect such spending stimulate investment spending? And so on. Here, too, rote memorization of the relevant part of an h.e.t. textbook would be helpful for answering the question correctly. But it would be a less reliable strategy than in the case of the Marx question.

Some summing up is due. What does all of the foregoing tell us about h.e.t. and the ECAES economics module before the redesign?

- First, h.e.t. held an important and well-defined place in the economic analysis module before the exam's redesign. Although it was given less weight than macroeconomics and micreconomics, it was understood as an essential testing ground for what were then posited as the core competencies of economics: interpretive, argumentative, and propositive.

- Second, the exam designers perceived a close connection between economic thought and economic history – closer, apparently, than between economic thought and the other core areas of economics. The connection is manifest in the way the two subject areas were juxtaposed for purposes of describing their place on the exam (see again Tables 1a and 1b). Even so, the questions in h.e.t. and economic history were given separately.H.e.t. questions were easily identifiable as h.e.t. questions and economic history questions as economic history questions. So too, and even more, were macroeconomics questions identifiable as such. No question was designed to be an h.e.t./economic history/macroeconomics question, at least not deliberately. One could imagine such a question: the Keynes question reproduced above comes close. But in both intention and effect that question is unmistakably about ''el pensamiento de Keynes,'' not about what macroeconomists today understand to be ''the Keynesian model,'' much less about the 1930s.

- Third, the h.e.t. questions were designed so as to make reading a textbook survey of the subject an effective way of preparing for the exam. The efficacy of studying a textbook survey was stated explicitly by ICFES/AFADECO in the Guía de Orientación. It was also suggested by the breakdown of the h.e.t. ''thematic content'' into individuals and schools of thought – a common organizational structure for h.e.t. textbooks. What was more, it was a natural if not inevitable consequence of the difficulty of getting students to do the creative or analytical work of history, as opposed to, say, macroeconomics, in answer to a multiple-choice question. One can posit a macroeconomic model and require a student to manipulate it in order to arrive reliably at a correct multiple-choice answer. But what would be an analogous question in h.e.t. or economic history? It is simpler to test a student's ability to distinguish true from false statements of historical fact. That is what the h.e.t. questions tended to do; and in preparation for that, the student did well to study the recommended textbooks.

2. Results

ICFES has made available the results for the Economics module of the old ECAES for 2006-2009.7 For the EAFIT, compared to other Colombian universities, the data show good if not outstanding results in Economics in general before the exam rewrite. From a certain perspective to be explained below, the EAFIT's results in the particular component of economic thought and economic history were better.

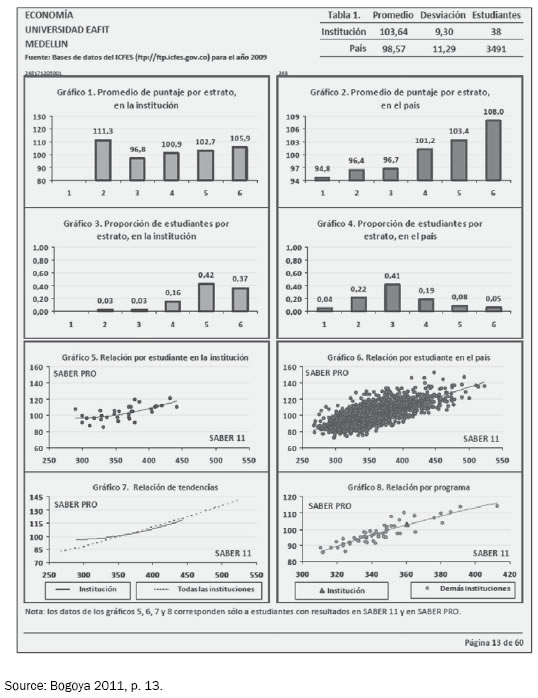

A 2011 report produced at the Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano uses ICFES data to study performances on the ECAES Economics module across Colombian universities in 2009 (Bogoya 2011). The mean score over all components of the Economics module for all 3,491 students throughout Colombia in 2009 was 98.57, with a standard deviation of 11.29; the mean for all 38 students taking the exam at EAFIT was 103.64, with a standard deviation of 9.30. Thus EAFIT students scored better than the mean – but less than one half of a standard deviation better, and below peer institutions like the Universidad de Antioquia (107.65), the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá (110.59), the Universidad de los Andes (115.35), and the Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá (106.07). A page of tables from the report showing the results at EAFIT relative to national averages is given in Appendix A.

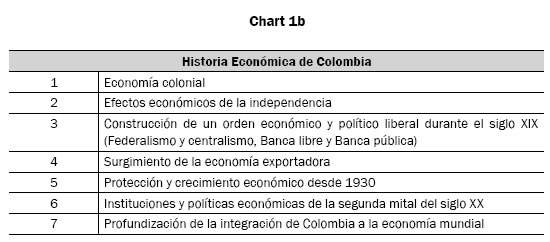

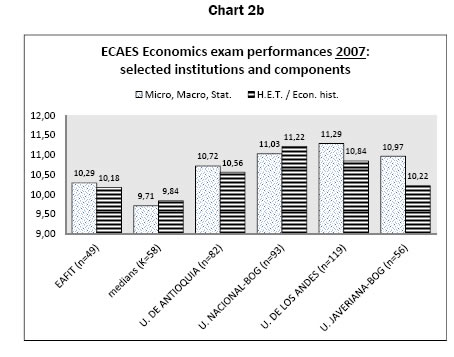

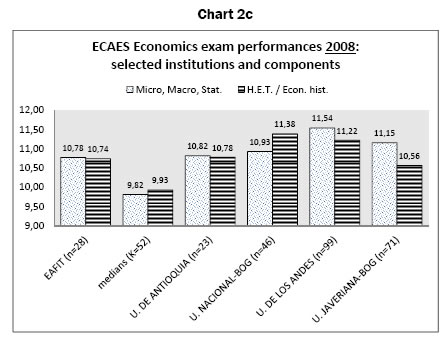

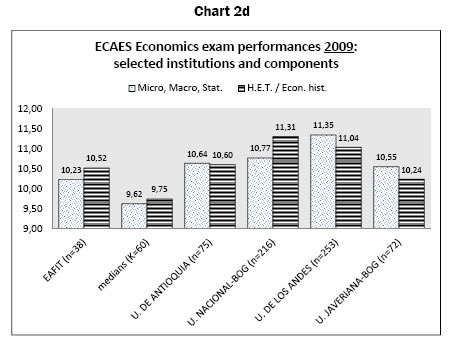

The Tadeo study, however, does not disaggregate the Economics scores by component. I have done so in Charts 2a-2d, below – not only for 2009, but for all four instances of the Economics module from 2006 to 2009. For the EAFIT and the foregoing peer instutitions (as well as the median of all institutions, numbering K in total), each table gives, on one hand, the simple mean of scores on all components of Economics except economic thought and economic history (i.e. macroeconomics, microeconomics, and statistics/econometrics); and, on the other hand, the mean score for economic thought and economic history.

The charts show that the results for 2009 were fairly characteristic of the results for the larger four-year span, even when breaking them down for non-historical versus historical exam components.The mean scores for EAFIT on the non-historical components were always below the scores of all four of the peer institutions. EAFIT scored relatively better in economic thought and economic history, where the mean score was only marginally below that of the Universidad de Antioquia in both 2008 (10.74 versus 10.78) and 2009 (10.52 versus 10.60), and well above that of the Universidad Javeriana in both years. Still, basic picture is this: on the Economics module's historical and non-historical components alike, the mean scores for EAFIT were above the median in all four years and below the scores of its select peers in most years.

The basic picture partakes of a bigger one. At a glance it plain enough to see that the variance of scores on the different components of the exam for each university is much smaller, by an order of magnitude or more, than the variance of scores on the particular component of economic thought and history among all universities. The observation has an important implication. If the purpose is to evaluate the effectiveness of EAFIT in teaching h.e.t. given the rest of the economics curriculum and the student body, then a comparison of mean scores between the EAFIT and other institutions is hardly relevant.Lower mean scores in economic thought and history at EAFIT compared to, say, the Universidad Nacional, are mainly the result of the overall superiority of the Nacional in the economics program and its student body. Unless a comprehensive overhaul of the economics curriculum and student body at EAFIT is contemplated, such scores tell us little that is useful. If economic thought and history scores are low, or if they are high, it is mainly for the same reasons that economics scores in general are low or high. Holding all else constant, there are no changes in the h.e.t. curriculum at EAFIT that could raise economic thought and economic history scores to the level of the Nacional – and few that could sink them to that of, say, the Universidad Autónoma Latinoamericana (typically a bit under the median).

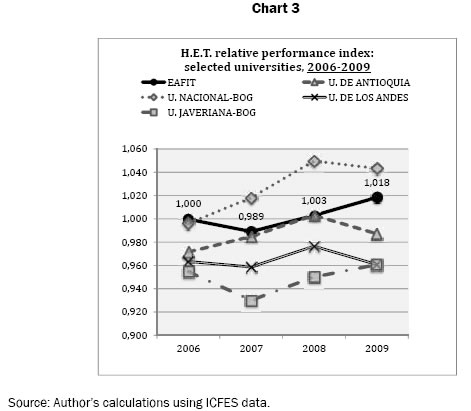

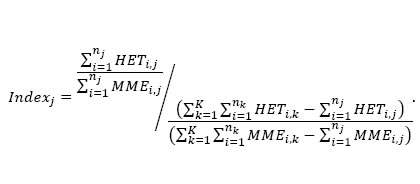

The purpose here is to determine whether EAFIT does well or poorly in h.e.t., and to think what it might do better in that area, given what EAFIT has to work with: the general structure of the larger economics curriculum and the students who enroll in it. To that end a better index of doing well or poorly is one that measures, for any given university, students' scores on the economic thought and history component relative to their scores on the non-historical components, taken as a proportion of the relative scores of all students in all other universities.

That is to say, a university does well in training students in economic thought and history– as opposed to doing well in attracting good students or providing well for them across the curriculum – not if they score better in economic thought and history than do students in other universities, but if they score better relative to their scores in micro, macro, and econometrics than do students in other universities.

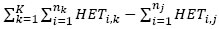

Let HETi,j be the score of student i at university j on the economic thought and history component of the Economic analysis module. Let MMEi,j be the simple mean score of the same student on the macroeconomics, microeconomics, and statistics and econometrics components. Let nj be the number of students taking the ECAES Economics module at university j, and let K be the number of universities with students taking the module. Then the aggregate exam score in economic thought and history at university j is  ; the aggregate score on the same component for all students in all universities except j is

; the aggregate score on the same component for all students in all universities except j is  ; and the aggregate scores for MME in each university, and for students in all other universities, take the analogous forms.

; and the aggregate scores for MME in each university, and for students in all other universities, take the analogous forms.

For university j, the relative performance index for economic thought and history is:

Chart 3 shows the index values for EAFIT and the foregoing four peer institutions over all four years for which ICFES makes the data readily available, from 2006-2009.

Here is a notably different picture of EAFIT's effectiveness in teaching h.e.t. The index value is always close to 1, implying that EAFIT generally does no better or worse than all other universities combined. The standard deviation of the index value across all universities ranges from a low of 0.025 (in 2006) to a high of 0.037 (in 2008); the value for EAFIT never departs from the institutional mean (which itself varies in a narrow range from 0.994 to 1.004) by more than half of one standard deviation. EAFIT is right in the middle of the pack of all Colombian universities.

Most notable, however, are index value's differences between EAFIT and the four select peer institutions. As in charts 2a–2d, there is a fairly stable ranking of the EAFIT and its peers over the four-year period. But here the ranking is different: at the top, the Nacional; second, EAFIT, with Universidad de Antioquia close behind; then Los Andes; and last, Javeriana.

In short, the data show that before the exam rewrite, given each university's larger economics curriculum and student body, EAFIT was performing at about the norm for all Colombian universities in training its students in economic thought and history; and performing as well as or better than its select peers, except the Nacional. If the data present any puzzle, it is not why EAFIT did well or poorly in training students in h.e.t. It is why the Nacional did so well, given its (already excellent) raw materials, and the Javeriana poorly. There will be occasion to return to this puzzle later, in section 4.

3. From the ECAES to the SaberPro Economics Module

The foregoing results date from five years ago and more. How relevant are they now that the ECAES and its Economic Analysis module have been redesigned?

The telling remark quoted earlier from the Guía, concerning the Economic thought and history component, may well be recalled: ''no obstante, la evaluación de este componente no puede ser de carácter memorístico.'' Under the old ECAES, the intention of ICFES and the exam's designers was not, by and large, to test the student's ability to affirm, deny, or relate facts. The intention was to test the student's ability to exercise a quality of judgment or employ methods characterizing a field of study. Nevertheless, as we have seen, testing the student's command of facts was largely what the Economic thought and history component did.

Official dissatisfaction with the old ECAES grew over the years. As early as 2005, Álvaro Montenegro of the Universidad Javeriana worried that ''los ECAES que se vienen aplicando, particularmente el de economía, son exámenes que están midiendo conocimientos en lugar de competencias'' (2005, p. 3; cited in AFADECO 2010, p. 11; emphasis added). A decree of the Ministry of Education dated October 30, 2009, reiterated that the ECAES's purpose was ''comprobar el grado de desarrollo de las competencias de los estudiantes próximos a culminar los programas académicos de pregrado'' (Decreto 4216, cited in AFADECO 2010, p. 12; emphasis added). With this criticism and purpose in view, ICFES undertook to redesign the ECAES. For the redesign of the Economic Analysis module, in late 2010 ICFES began work with the Asociación Colombiana de Facultades, Programas y Departamentos de Economía (AFADECO). They aimed at:

el desarrollo de una prueba de competencias genéricas que efectivamente mida competencias a través de preguntas que simulen más adecuadamente lo que Montenegro llama ''poner a la persona directamente en actividad.'' (AFADECO 2010, p. 12)

A constraint in redesigning the test was that the questions should remain multiple choice. But multiple-choice questions are difficult to reconcile with the purpose of testing competencies instead of factual knowledge. It was probably with that difficulty in view that, in the foregoing quotation, the AFADECO authors referred to ''preguntas que simulen'' the competencies.

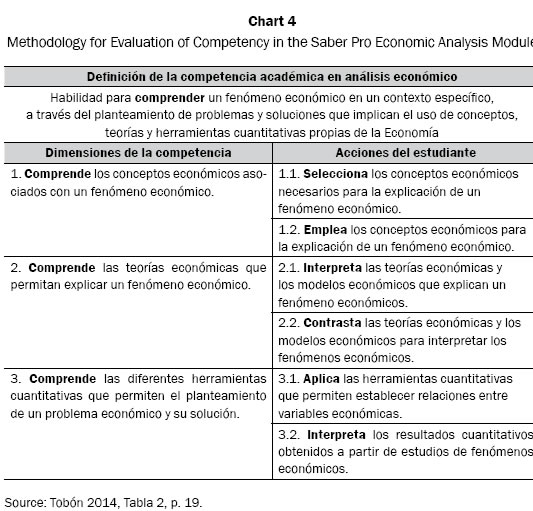

The competencies themselves were redefined. AFADECO has now defined competency in economics – more specifically, academic competency in economics – as ''habilidad para comprender un fenómeno económico en contexto y proponer soluciones a problemas específicos a partir de conceptos, teorías y herramientas propias del análisis económico.''8 Gone are the erstwhile interpretive, argumentative, and propositive competencies from the pre-2012 ECAES Economics module. The aforementioned concepts, theories, and tools – now referred to as academic ''sub-competencies'' or ''dimensions of competency'' in economics – have become the main organizing categories of exam questions.

In short, in the writing of exam questions for the new SaberPro Economics module, ''sub-competencies'' or ''dimensions'' have taken the place of ''components.'' In consequence, concepts, theories, and tools havesupplanted macroeconomics, microeconomics, statistics and econometrics, and economic thought and history. The upshot is that questions about economic thought and history per se no longer exist in the SaberPro Economics module.

Yet questions that invoke economic thought and history still exist. They are recategorized, so they do not exist as such. They exist instead as means of eliciting ''evidence'' (or ''actions'') to corroborate ''affirmations'' (or ''dimensions'') of a student's knowledge of concepts, theories, or tools.

The structure of the new exam (now reduced to 40 multiple-choice questions, each with a single correct answer9) is explained in detail in documents by Alexander Tobón of the Universidad de Antioquia, Coordinator of the AFADECO Comisión de Competencias (Tobón 2013, 2014). Each ''affirmation'' or ''dimension'' of competency in an economic concept, theory, or tool is tested by eliciting one of two different ''evidences'' or ''actions.'' See Chart 4, taken from Tobón's document.10

While any of the actions described in the chart's right-hand column could be elicited by questions with h.e.t. content, some are more likely grounds for h.e.t. than others. Action 1.2, for instance, which entails using economic concepts in order to explain a phenomenon in a specific context, could be elicited by a question with an intellectual-historical context: say, the concept of the division of labor in the context of Adam Smith's thought. Action 2.1, which entails interpreting economic theories and models in order to explain economic phenomena, could be elecited by a question about the potential of Ricardian rent theory to explain differential rents in rural versus urban areas. Action 2.2, which entails setting economic theories in contrast in order to interpret economic phenomena, could be elicited by a question contrasting Keynesian and Hayekian theories of business cycles in order to interpret the significance of economic depression.

This is guesswork about how h.e.t. could appear in the SaberPro Economics module. How it does appear is another question. The information that ICFES and AFADECO have released to date is suggestive of the answer, but it is far from conclusive. The ''Guía Informativa Para la Presentación del Módulo Específico de Análisis Económico del Exámen de Estado Saber Pro'' (Tobon 2014) includes several examples of exam questions in each of the three dimensions of competency. Among those examples, which number forty-five, just one of them pertains to the history of economic thought:

13) El concepto de reproducción simple hace parte de la contribución de Karl Marx a la teoría económica. Este concepto permite entender uno de los siguientes problemas económicos: A. El crecimiento positivo de un país con una composición orgánica de capital constante. B. La crisis en economías capitalistas con tasas de plusvalía iguales al 100% del costo salarial. C. La explotación laboral bajo el supuesto de una relación capital-trabajo constante. D. La ausencia de crecimiento económico en razón del consumo improductivo de la plusvalía.

[Clave: D] (Tobon 2014, p. 31, 43)

The question bears some resemblance to the questions on Marx that appeared in the Guía for the ECAES Economics exam in 2004-2009 and on the exam proper in 2004, and that were cited earlier in this document on p. 5 and in footnote 6. It appears to elicit action 1.2, the employment of an economic concept (reproducción simple) for explaining and economic phenomenon (la ausencia de crecimiento económico).

Apart from the document containing the latter example of an h.e.t. question for the SaberPro Economics module, members of the Comisión de Competencias have kindly given the present author other examples of such questions, so far as their confidentiality agreements allow.11 The two examples are roughly similar to the imagined ones for actions 2.1 and 2.2 a few paragraphs above. Both posit a context of economic crisis, specifically 1929, and have the student assume the role of an economic adviser. Both ask the student which policy instrument or macroeconomic variable should be adjusted in order to alleviate the crisis. The first supposes that the student has offered advice to the effect of moving a macroeconomic variable in a certain way, for example, reducing the real interest rate. The question is, what may be inferred about the diagnosis and policy instrument? Over-production that might be corrected in the long-run without policy intervention? Insufficiency of effective demand that requires some specific response (which is presumably stated in alternative answers) by the fiscal or monetary authorities? The second question reverses the scenario: instead of supposing that a macro variable moves in a certain way and deciding which policy instrument must have been adjusted, the student is asked to suppose the adjustment of a certain policy instrument and decide how a certain variable would have moved.

The historical content of the questions described above lies partly in their invocation of the economic context of 1929 – although, without more detail, it is hard to see the relevance of that context beyond a generic crisis scenario. It lies partly in their invocation of historical ideas – although here too the lack of detail obscures history's relevance. One of the EAFIT students who took the exam in 2013 recalls a question matching the descriptions above, and recalls further that the question was ''about'' Keynes.12

From these few and rather different examples – the one concerning Marx and requiring the employment of an economic concept, the others loosely concerning Keynes and the interpretation or the contrast of economic theories – it is impossible to draw fixed and detailed conclusions about the presence of h.e.t. in the SaberPro Economics module. But a couple of preliminary and broad conclusions do see warranted.

First, questions with h.e.t. content will surely be fewer in absolute number, and will probably be a smaller proportion of all questions, than they were under the old ECAES. Second, even while some of the questions with h.e.t. content may hearken back to those under the old ECAES, overall the questions are indeed likelier to test students' ability to use judgment or employ methods characterizing a field of study than to test their command of facts.

What, then, do these preliminary and broad conclusions imply for the teaching of h.e.t.? Four things:

i. A textbook survey of h.e.t. may still be a helpful way of preparing for the exam, but less so than under the old ECAES. Inasmuch as the new SaberPro Economics module contains questions pertaining to h.e.t., students may benefit from familiarity with certain historical figures in economics and their concepts, theories, or tools: Adam Smith and the division of labor, Ricardo and his theory of rent, Marx and simple reproduction, Keynes and various monetary or fiscal policy instruments. But a textbook survey of those historical figures' ideas offers less preparation for the exam than before.

The textbook itself will probably not give much practice in the use of judgment or the employment of methods.It may give information that is helpful in ruling out one or more incorrect answers, or in forming a hunch about the correct answer. But inasmuch as the distinction between the correct answer and at least one of the three alternatives is not a matter of fact, the correct one is unlikely to be found conclusively in any particular chapter or page of a textbook.

ii. The benefits of h.e.t. courses of any kind, although great, have become less straightforward than they were before. If achieving high scores on the SaberPro Economics module is the goal – or if the goal is different, but high economics-module scores are a good proxy for it – then the main benefit of h.e.t. courses lies in the impetus they give students to practice some of the ''evidences'' or ''actions'' mentioned above and listed in Chart 4. To wit, employing economic concepts in context, understanding the potential (and limits) of economic theory for interpreting economic phenomena, and applying economic theories in the framework of an economic phenomenon.

As it happens, such a benefit aligns closely with the pedagogical virtues of h.e.t. that scholars in the field have been emphasizing for years. It may be noted that each of the evidences cited in the previous paragraph is, in some respect, a question of judiciuosness in the application of economic ideas. Judiciousness, like other skills, is honed by practice – but practicing this skill requires a large canvas. It requires thinking repeatedly about instances where the applicability of certain economic concepts, theories, or tools is debatable. They may apply well or poorly depending on the context. Practice entails inserting oneself into the debate and deciding. The narrative of past debates and their consequences, theoretical or methodological or political, does not offer the only canvas for such practice, but it offers the largest.

This is the meaning of one eminent American historian of economics where he says that ''once [students] are immersed in the narrative of the discipline, as opposed to the mere acquisition of technical skills, they are better able to reason and use what they have learned'' (Bateman 2002, p. 26). In Colombia, it was the meaning several decades ago of Lauchlin Currie, who said that economists needed not only technical training but also a certain ''cualidad de juicio'' that h.e.t. could help provide (Currie 1967, pp. 54, 58). And it is the meaning nowadays of two prominent Colombian historians of economics who promote h.e.t. as a ''reserve of meaning and good sense'' for economists and economic theory (Álvarez and Hurtado 2010a, p. 3; 2010b, p. 279).

Here is a strong case for h.e.t. But it must be argued strongly, because it is not nearly as straightforward as observing, as one could have done in the past, that the ECAES Economics exam has several questions devoted expressly to the history of economic thought, therefore, to score well on the economics exam, students must take courses in the history of economic thought.

iii. The prominent place of h.e.t. in Colombian university curricula – as in SaberPro Economics module questions – would appear to be tenouous in the long run.

The ubiquity of the h.e.t. in the economics curricula of Colombian universities is remarkable in light of the long-term decline of the subject in U.S. and Europe (Mirowski 2002). The decline has not been uniform or steady: it varies by place (h.e.t. has lost more ground in the United States than in Europe), type of institution (courses are scarcer in research universities than in liberal arts colleges) and over time (the recent economic crisis seems to slowed the losses). But the trend is unmistakable. The reason for Colombia's resistance to the trend would be a worthy subject for investigation. It appears to be rooted in the emphasis given by Colombian economics faculties, since at least to the 1960s, to teaching different schools of economic thought (Flórez 2009, p. 216). Such emphasis mirrored the system of political power sharing during that era, when ideological differences among the Colombian elite were diverted to peaceful channels by giving each side its calculated share of positions and patronage. To be sure, as an explanation of the origin of h.e.t.'s firmer foothold in Colombia's universities, this is speculation (although see Cataño [1995], p. 150 and passim, for corroboration). In any case, whatever may be its origin, in recent years it has been secured at least in part by the ECAES Economics exam and its legacy.

Maintaining the foothold will probably require either the continuing presence of questions invoking h.e.t on the SaberPro Economics module, even if such questions are not categorized as h.e.t.; or widespread acknowledgment of the pedagaogical benefits of h.e.t., even if questions invoking the subject were to disappear from the SaberPro Economics module.

Some presence of questions invoking h.e.t. in the SaberPro Economics module is assured so long as two of six members of the AFADECO Comisión de Competencias, including the commission's coordinator, are prominent historians of economic thought.13 Whether that is likely to remain the case during the entirety of the 12-year run of the current SaberPro exam,14 let alone afterwards, is a question that others will be more able to answer.

Widespread acknowledgment of the benefits of h.e.t. in the Colombian economics curriculum irrespective of SaberPro seems assured for the next several years. The many faculty members currently teaching h.e.t. in Colombia will make the case in their respective institutions. They are aided by compelling expressions of the case in the Colombian economics literature (e.g. Gómez and Tobón 2009, Álvarez and Hurtado 2010b). Whether other, especially newer, faculty members will be receptive to the case in the future is another matter.The growing number of Colombian economics faculty members with Ph.D.s from U.S. graduate programs, where h.e.t. has mostly vanished, makes one wonder.15

Could the redesign of the old ECAES Economics module, so that h.e.t. may be invoked but need not be covered, be the thin end of the wedge that drives h.e.t. first out of SaberPro, then out of the curriculum?

In order to avoid that outcome, the compelling case that Colombian historians of economics have already made for the subject must be repeated, and demonstrated, for new cohorts of economists.

iv. The new exam may offer some evidence of the pedagogical benefits of h.e.t.But the strength of the evidence will depend on ICFES's release of more data than they currently do.

One advantage of the new exam is that it is now likelier that the pedagogical benefits of h.e.t. will be evident in results for questions that do not invoke h.e.t.. But unless ICFES releases data disaggregated by question instead of by section, the evidence will be elusive.

Some weak evidence may be extracted from the results disaggregated by section, as soon as ICFES makes them available. Assuming the unlikelihood of Colombian unversities' curricula having changed much between, say, 2010 and 2013 (the four-year span including the last two years of the old ECAES Economics module and the first two of the new), and assuming also that (a) the questions that invoke h.e.t. are most likely to be found in section 2 of the exam, concerning theory; and (b) the indirect benefits of h.e.t. are also more likely to be felt in section 2 than in sections 1 and 3; then it is reasonable to hypothesize that the same universities that score high on the h.e.t. relative performance index for 2010 and 2011 will also score high on an analgous index for relative performance on section 2 for 2012 and 2013.

That is to say, if the Universidad Nacional remained on top of the h.e.t. relative performance index ranking in 2010-11, then it would probably be on top of a ''section 2 relative performance index'' ranking for 2012-13. The reason would have to do partly with the direct benefits of relatively good preparation in h.e.t. for the questions that invoke h.e.t. in section 2. But it would also have to do with the indirect benefits of relatively good preparation in h.e.t. for non-h.e.t. questions, especially those in section 2, which aims to test students' understanding of the scope and contextual application of economic theory.

4. H.E.T. in the Economics Curriculum at EAFIT

The economics curriculum in Colombian universities is highly structured, with students taking required courses for most credits throughout most semesters of their undergraduate career. At EAFIT, a full slate of required courses in mathematics and economics are required in the first through the fifth semesters. Students begin taking elective courses together with required ones in the sixth semester. They continue taking electives through the eighth semester, and finish the degree with a graduation project in the ninth semester.

Among the required courses at EAFIT are two in h.e.t. in the student's fourth and fifth semesters and a course in Colombian economic history in the sixth. Students typically take the SaberPro exam in their fourth year, in the seventh or eighth semester. By that time they have finished all required courses in microeconomics and macroeconomics (''general,'' ''interemedia I,'' and ''intermedia II'' for each), statistics (I and II), econometrics (I and II), the aforementioned courses in economic thought and history, and some field courses that are required not elective: international economics, economic growth and development, and game theory. All these, in addition to other required courses in mathematics, accounting, the contemporary Colombian economy, and more.16

The two h.e.t. courses are divided more or less chronologically. The fourth-semester course, ''Pensamiento Económico I'' (EC0221) taught usually by Mauricio Andrés Ramírez, treats economic thought from Ancient Greece and Rome through the classical works of Smith, Ricardo, Mill, and Marx. It also includes a section on ''Economía clásica contemporánea'' concerning the Sraffian reformulation of classical economics. The readings include secondary works, especially chapters from Landreth and Colander's text, supplemented by original ''classic texts'' (e.g. selections from Aristotle's Politics, Smith's Wealth of Nations, and so on) and other secondary ones, most notably Mark Blaug's Economic Theory in Retrospect.17

The fifth-semester course, ''Pensamiento Económico II'' (EC0222) taught usually by Luís Guillermo Vélez, treats economic thought from the advent of marginal utility, marginal productivity, and general equilibrium theories (Menger, Jevons, Marshall, Walras) through the Keynesian revolution, the birth of macroeconomics, and the opposing theories of the Austrian school. The course ends with ''other developments'' in modern economics including the new institutionalism, Sraffian economics (once again), public choice, and economic justice in light of John Rawls and Amartya Sen. The readings, as in Pensamiento Económico I, include both textbook surveys (here too, Landreth and Colander, as well as others) and original works from Böhm-Bawerk to Jevons, Keynes, Hayek, and more.18

In short, both courses make use of textbook surveys of economists and economic theories, but that is not all. Both also make use of numerous original texts. During some parts of the courses, both appear to attempt a ''rational reconstruction'' of past ideas, putting them in close dialog with ideas of the present. In EC0221, Blaug's text is the marker of this approach; in EC0222, the juxtaposition of, for example, Keynes and rational expectations. But in other parts of the both courses they undertake ''historical reconstruction'' of the same ideas, treating the material conditions and broader intellectual or political contexts that gave rise to them. In EC0221, this approach is evident in the discussion of the transition from feudalism to capitalism, the formation of nation-states, and the manifestations of both phenomena in mercantilist thought.In EC0222, the approach is less evident in the syllabus but was apparent in Vélez's description of his lectures during personal conversation.

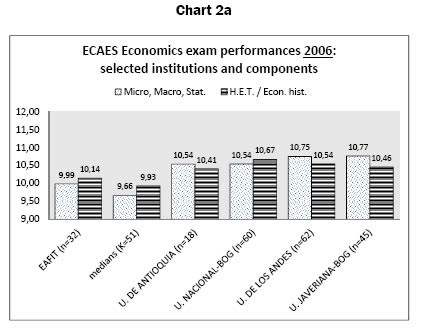

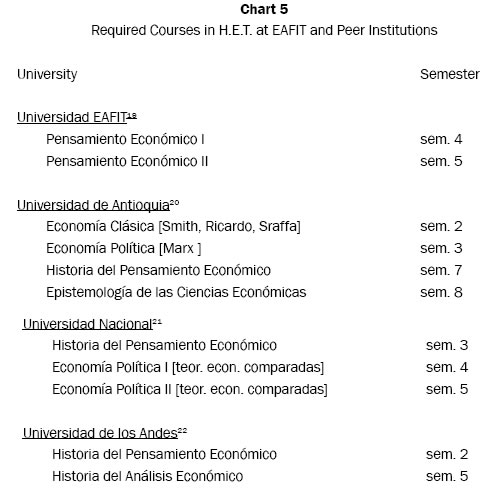

It is worthwhile to compare EAFIT's offerings of h.e.t. with those of the UdeA, Nacional, Los Andes, and Javeriana. The differences are presented briefly below in Chart 5.

The number, timing, and nature of h.e.t. courses across the universities vary widely. The public universities offer more h.e.t. courses, including more courses devoted explicitly to comparative-schools or alternative-paradigms approaches. The private universities offer fewer h.e.t. courses: two at EAFIT and Los Andes and one at Javeriana. They also organize their courses differently from public universities, and even more from each other, in respect to the courses' content and timing within the Plan de Estudios. The most striking example is the Javieriana's single h.e.t. course offered in the first semester.Such is course is presumably meant to be an ''appetizer'' for the whole economics curriculum.

It is worth pausing to note the result of the Javeriana model – not, that is to say, of the early appetizer, but of eschewing any other h.e.t. course. The lack of an opportunity to use history for deeper reflection about economic theories that students have already encountered, combined with the long time lag between the student's exposure to h.e.t. and the ECAES, is the likely explanation of Javeriana's poor relative performance in h.e.t., as illustrated in part 2 of this report.

EAFIT and Los Andes both offer two h.e.t. courses, but with different divisions of course material. Whereas the material in EAFIT's two courses is divided chronologically, with a break point in the late 19th century, Los Andes offers an appetizer course like Javeriana. Unlike Javeriana, though, Los Andes follows up with a second course featuring the same principal authors – Smith, Ricardo, Marx, and Keynes, and others depending on the instructor – in more theoretical depth after students have already encountered contemporary microeconomic and macroeconomic theory.

These alternative ways of positioning h.e.t. in the economics curriculum, together with the data presented in part 2, may shed some light on the state of h.e.t. at EAFIT, the options for offering it differently, and the likely consequences of the options. Some conclusions:

i. The EAFIT does pretty well in the teaching of h.e.t. The number of h.e.t. courses is reasonable given the EAFIT's mission and niche. So is the courses' content. And past ECAES scores suggest they yield good results.

The case for h.e.t. as part of the training of economists has already been stated well by others and recpitulated in section 3. Besides that case, this report alluded to another that may have helped establish the subject's remarkable foothold in the Colombian economics curriculum: the invocation of economic thought of the past in order to promote ideological pluralism in the present. The EAFIT, it may be observed, has that purpose inscribed in its mission statement, and even in plaques on classroom walls.24 In light of a number of good purposes for offering courses in h.e.t., one might think that the EAFIT should offer a number of them – and that the number should be greater than two. Why not go the route of the Nacional and bump it up to three, let alone the UdeA and four?

The main reason is that although it may be useful to compare the EAFIT to its peers, it is may not be desirable to emulate them in all respects even where they are excellent. Economics at the EAFIT has a calculated niche in the national marketplace:

La intención de diferenciar al economista de EAFIT de sus pares en el ámbito regional y nacional se centró fundamentalmente, en la posibilidad de aprovechar las ventajas competitivas que, en el campo de las finanzas, el mercadeo y la administración, han caracterizado a la institución a lo largo de su historia.25

The EAFIT's present course offerings h.e.t. are helpful to the end of training economists to employ their theories and methods judiciously. The number of h.e.t. courses is great enough and their timing adequate to help students reflect on the scope and application of contemporary economic theory; yet the number is low enough to make room for the other courses in finance, marketing, and administration that distinguish EAFIT from its peers.

In addition, the content of the EAFIT's h.e.t. courses, including both original texts and textbook surveys, historiographies of both historical and rational reconstruction, and a chronological organization covering numerous historical figures and centuries of economic thought, appears to give good preparation for the new ECAES Economics module as it did for the old. Of course this conclusion will need to be updated when ICFES makes new data available.

ii. If an alternative organization for the EAFIT's h.e.t. courses were entertained, it could reasonably be that of Los Andes. It could not be Javeriana's. But the EAFIT would do better to stick with the status quo unless and until evidence shows that it yields inferior results.

The ''appetizer'' h.e.t. course at Los Andes is offered in the second semester, after students have had at least Introduction to Micreconomics. Not so at Javeriana. And Los Andes' practice of following the appetizer with a second course, after students have finished with most of their intermediate and advanced theory, has the pedagogical benefit of revisiting both history and contemporary theory in a new and sophisticated light.

On the other hand, the Los Andes model covers a shorter span of historical time and allows coverage of fewer historical figures. No Aristotle, no Nicholas Oresme, no Luís de Molina, and apparently no Friedrich von Hayek.26

It is hard to say which model, that of Los Andes or the EAFIT, is better for the broader purposes of h.e.t. in the economics curriculum or even the narrower one of preparation for the ECAES Economics exam. Unless there is a clear desire among either the professors or the students for a different approach, the EAFIT would do well to maintain the status quo.

iii. There may, however, be marginal changes to the EAFIT's h.e.t. courses that could serve the broader purposes of h.e.t., the narrower purpose of ECAES exam preparation, and the wishes of students all at once.

To return to an idea introduced in section 3: the touchstone of any changes should be the judiciuosness they foster in the application of economic ideas. Any changes should help students to think about instances where the applicability of certain economic concepts, theories, or tools is debatable, and then insert themselves in the debate.

Some tinkering with the readings and their ordering can help. The general structure of courses need not be changed: they could still proceed more or less chronologically over two semesters and engage the ideas of many authors, as they have been doing successfully. But in particular instances the authors might be grouped differently, or different readings might be selected, in order to promote debate.

For instance: Ricardo, Malthus, and J.-B. Say might be pulled even closer together by focusing on selections of their work in which they refer to one another. This could be done by including among the selections from Ricardo's Principles of Political Economy and Taxation ch. XXI, where he casts doubt on the possibility of a general glut of commodities. The next week, in treating Malthus, one could focus on ch. 7 of Malthus's own Principles, in which he picks on Ricardo's argument in ch. XXI; to that one could juxtapose selections from Say's Letters to Mr. Malthus, where Say disputes the reasoning of Malthus's ch. 7 and develops what came to be known as ''Say's Law.'' Through such selections students could acquire a vivid understanding of the meaning of Say's Law and why it is worth debating.Is there any such thing as a general glut? Should we think of depressions as macreconomic maladies or as sectoral maladjustments? How does one know whether one way of thinking or another is most apt, and why does it matter?

For another instance, instead of treating Keynes and Hayek separately one might juxtapose them, perhaps by reading a bit of the General Theory followed by one of Hayek's works that is critical Keynes.27

By emphasizing debate and judgment, such reshuffling of readings could stimulate students to think more critically about the economists and their theories. Inasmuch as it enlivens the material, it may also help to stimulate their memories when they sit down for the SaberPro exam a year or two later.

A corresponding change in the method of evaluation could be entertained. Students enter into debate meaningfully only when they give voice to arguments or put them in writing. The weight of evaluation might be shifted accordingly to emphasize more oral and written work.

Evaluating written work is costly, but there are ways of reducing the cost. Let some of the written work be preparatory briefs for an oral debate, and let the professor check the debate briefs only for completeness. The numerical score could be reserved for debate performance. Another possiblity: let much of the written work be short papers of 1 or 2 pages, which are submitted weekly via EAFIT Interactiva and checked only for completeness. But give students an incentive to be diligent in writing them by making a final paper, of perhaps 10-15 pages, an extension or revision of some of the shorter ones.

It bears mentioning that two of the three students in our March interview, namely Mateo Castro and Joaquín Andrés Urriego, suggested more emphasis on writing as a way of deepening students' understanding of the theories that are surveyed (Castro) and of improving memory of them for the ECAES (Urriego).

5. Conclusion

A review of part of the curriculum gives the reviewer a certain inclination to recommend big changes, to shake things up. Otherwise, was the effort worthwhile?

Fair reflection does not allow such a recommendation for the history of economic thought at EAFIT. This report corroborates the wisdom of the current place of h.e.t. in the economic curriculum.The number and content of the h.e.t. courses at EAFIT are suitable for the university's mission and its niche in Colombian higher education. The courses are suitable for the purpose of training better economists who can apply their theories and methods judiciously. The available evidence shows they are suitable, too, for for the narrower purpose of preparing students for the SaberPro Economics module – although this conclusion awaits further corroboration from results of the exam since its redesign.

Until the latest results become available, any changes to EAFIT's h.e.t. courses should be marginal and agreeable to the professors who already teach the courses successfully. Among the changes that might be considered are minor rearrangements of readings and more writing assignments to heighten the students' feeling of direct engagement in theoretical debates in the history of economic thought.

* This report was invited by Juan Felipe Mejía Mejía in February 2014, shortly after I arrived at EAFIT as a visiting faculty member for the spring semester of 2014. I am grateful to him, Gustavo Canavire, and Alejandro Torres for the opportunity to visit the Departmento de Economía and participate in the faculty. The conclusions drawn here are mine alone.

1 Document ''ECAES_2011'', attached to email correspondence of Catalina Gómez Toro to Stephen Meardon, 19 March 2014; also in Guía 2009, p. 20.

2 ICFES 2013, p. 24.

3 The Guías de Orientación for the exam from 2006 to 2009 are available at ftp://ftp.icfes.gov.co/SABERPRO/, by consent of ICFES. Henceforth ''Guía'' 2006-2009.

4 Guía 2009, pp. 18-19.

5 Guía 2004, p. 26; 2009, p. 25. It is worth observing that the question is qualitatively similar to a question on Marx that did appear on the 2004 exam, according to one of the few actual exam documents released by ICFES/AFADECO:

88. Según la teoría económica de Marx, el desarrollo del sistema capitalista de producción,

dada una tasa de plusvalía constante, genera que la tasa media de ganancia tienda a

A. aumentar, porque la composición orgánica del capital aumenta

B. disminuir, porque la composición orgánica del capital aumenta

C. aumentar, porque la composición orgánica del capital disminuye

D. disminuir, porque la composición orgánica del capital disminuye

Clave: B. (See ''Pruebas Aplicadas en Noviembre de 2004,'' p. 29, and ''Respuestas,'' http://www.afadeco.org.co/Saber-PRO/ECAES/Pruebas-ECAES, accessed 10 July 2014.)

6 Guía 2009, p. 27.

7 ICFES (2013, pp. 26-30) says in one instance, alluded to earlier, that data are available for all SaberPro exams [meaning, presumably, ECAES exams] from 2004 to 2010 (p. 26); in another instance, that data for the exams' components are available from 2007 to 2009 (p. 27). The contens of the ftp data site do not conform precisely to either statement. I found, and will use here, data for performance on the Economics module of the ECAES by individual students across Colombian universities over the period 2006 to 2009. ICFES disaggregates individual performances only so far as the ''component'' level of the exam (i.e. macreconomics, microeconomics, statistics & econometrics, economic thought and history), not the question level. I aggregated up individual performances on the various components by university. Data were taken from ftp://ftp.icfes.gov.co/ during June to August 2014 following instructions from ICFES (2013).

8 AFADECO, ''Módolo en Análisis Económico,'' http://www.afadeco.org.co/Saber-PRO/Modulo-en-Analisis-Economico, accessed 11 Aug. 2014. Emphasis added.

9 AFADECO, ''Módolo en Análisis Económico,'' http://www.afadeco.org.co/Saber-PRO/Modulo-en-Analisis-Economico, accessed 11 Aug. 2014.

10 See also Tobón 2013, ''Las especificaciones de la prueba del Módulo Análisis Económico,'' p. 10. The specifications of the exam questions as described in the 2014 document differ semantically from those of 2013, so that (for example) ''dimensions'' replace ''affirmations'' and ''actions'' replace ''evidences.'' But the gist remains the same.

11 Jimena Hurtado, conversation of 10 March 2014 and correspondence of 13 Aug. 2014; Alexander Tobón, conversation of 23 May 2014.

12 Mateo Castro Uribe, conference of 27 March 2014.

13 Alexander Tobón (coordinator) and Jimena Hurtado. See Tobón 2013, p. 2.

14 Tobón 2013, p. 4.

15On the trend of Colombian economists undertaking doctoral studies at U.S. universities, see Flórez 2010, pp. 217-218.

16 ''Plan de estudios - Carrera de Economía - Universidad EAFIT,'' http://www.eafit.edu.co/programas-academicos/pregrados/economia/informacion-general/Paginas/plan-de-estudios-economia.aspx#.U-5ylmv2-L4, accessed 15 Aug. 2014.

17 Syllabus for EC0221 by Mauricio Andrés García, 2014-01, email MAG-SJM of 18 March 2014.

18 Syllabus for EC0222 by Luís Guillermo Vélez A., 2014-01, email LGV-SJM of 18 March 2014.

19 http://www.eafit.edu.co/programas-academicos/pregrados/economia/informacion-general/Paginas/plan-de-estudios-economia.aspx#.U-7CC7xdXSh, accessed 15 Aug. 2014.

20 http://www.udea.edu.co/portal/page/portal/SedesDependencias/CienciasEconomicas/B.Institucional/C.DependenciasAcademicas/Economia/C.planEstudio, accessed 15 Aug. 2014.

21 http://www.fce.unal.edu.co/media/files/documentos/cecono/plan_de_estudios_economia.pdf, accessed 15 Aug. 2014.

22 http://economia.uniandes.edu.co/programas/Pregrado_en_Economia/Estructura_y_plan_de_estudios, accessed 15 Aug. 2014.

23 http://puj-portal.javeriana.edu.co/portal/page/portal/Facultad%20de%20Ciencias%20Economicas%20y%20Administrativas/pre_econo_plan1, accessed 15 Aug. 2014.

24 ''La Universidad EAFIT tiene la Misión de contribuir al progreso social, económico, científico y cultural del país, mediante el desarrollo de programas de pregrado y de posgrado -en un ambiente de pluralismo ideológico y de excelencia académica ... ,'' http://www.eafit.edu.co/institucional/info-general/Paginas/mision-vision.aspx#.U8BEG1wQ0ms, accessed 11 July 2014.

25 ''Presentación – Carrera de Economía, Pregrados,'' http://www.eafit.edu.co/programas-academicos/pregrados/economia/informacion-general/Paginas/presentacion.aspx#.U-5z12v2-L4, accessed 15 Aug. 2014.

26 See Uniandes syllabi for Andrés Álvarez and Jimena Hurtado, Historia del Pensamiento Económico, 2014-10; José Felix Cataño, Historia del Análisis Económico, 2014-1; and Hernando Matallana, Historia del Análisis Económico, 2014-1, all available at http://economia.uniandes.edu.co/programas/Pregrado_en_Economia/Programas_academicos_de_los_cursos, accessed 15 Aug. 2014.

27 E.g. ''The Keynes Centenary: The Austrian Critique,'' ch. 13 in Bruce Caldwell, ed., The Collected Works of F. A. Hayek, vol. 9 (University of Chicago Press, 1995): 247-255.

References

Álvarez, Andrés and Jimena Hurtado. (2010a) ''Why Teach the History of Economic Thought Today?'' Universidad de los Andes, Serie Documentos CEDE, 2010-28; SSRN Working Paper no. 1705530. [ Links ]

Álvarez, Andrés and Jimena Hurtado. (2010b). ''Amenazas y Ventajas de la Enseñaza de la Historia del Pensamiento Económico Hoy.'' Lecturas de Economía No. 73 (Julio-Diciembre): 275-301. [ Links ]

Asociación Colombiana de Facultades, Programas y Departamentos de Economía (AFADECO). (2010). Documento de Identificación de Competencias Fundamentales en Economía. Bogotá, Diciembre. [ Links ]

Bateman, Bradley W. (2002). ''Sitting on a Log with Adam Smith: The Future of the History of Economic Thought at Liberal Arts Colleges.'' History of Political Economy 34 (Suppl.): 17-34. [ Links ]

Bogoya M., Daniel. (2011). ''Elementos de Calidad de la Educación Superior en Colombia, con Base en Resultados SABER PRO 2009: Caso de Estudio, Economía.'' Documento de Universidad de Bogota Jorge Tadeo Lozano, 28 de Marzo. [ Links ]

Cataño M., José Félix. (1995). ''Los Cursos de 'Economía Política' en el Pensum de las Facultades de Economía: Algo de su Historia y de su Justificación Actual.'' Lecturas de Economía de la Universidad de Antioquia no. 43 (Julio-Diciembre): 145-165. [ Links ]

Currie, Lauchlin. (1967). La Enseñanza de la Economía en Colombia. Bogotá: Ediciones Tercer Mundo. [ Links ]

Flórez Enciso, Luís Bernardo. (2010). ''Colombia: Economics, Economic Policy and Economists.'' Ch. 5 in Verónica Montecinos and John Markoff, eds., Economists in the Americas (Northampton, Mass.: Edward Elgar): 195-226. [ Links ]

Gómez, Rebeca and Alexander Tobón. (2009). ''In Search of a Definition For the History of Economic Thought.'' Lecturas de Economía 71 (julio-diciembre): 235-250. [ Links ]

Instituto Colombiano para la Evaluación de la Educación (ICFES). (2013). Guía de Acceso a Bases de Datos ICFES. Bogotá, Febrero. http://www2.icfes.gov.co/investigacion/component/docman/doc_view/3-guia-de-acceso-a-baskeyneses-de-datos-icfes?Itemid= [ Links ]

Mirowski, Philip. (2002). ''A Pall along the Watchtower: On Leaving the HOPE Conference.'' History of Political Economy 34 (Suppl.): 378-390. [ Links ]

Montenegro, Álvaro. (2005). ''Los ECAES de Economía.'' Bogotá: Documentos de Economía no. 003164. [ Links ]

Tobón, Alexander. (2013). ''Módulo de Análisis Económico del Examen Saber-Pro Informe Final.'' Bogotá: AFADECO. Available at http://www.afadeco.org.co/Saber-PRO (accessed 11 July 2014). [ Links ]

Tobón, Alexander. (2014). ''Guía Informativa Para la Presentación del Módulo Específico de Análisis Económico del Exámen de Estado Saber Pro.'' Medellín: AFADECO, June 7. [ Links ]

Appendix A: