Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Perfil de Coyuntura Económica

versión On-line ISSN 1657-4214

Perf. de Coyunt. Econ. no.17 Medellín jun. 2011

COYUNTURA Y POLÍTICA ECONÓMICA REGIONAL

The logic of the violence in the civil war: The armed conflict in Colombia

La lógica de la violencia en la guerra civil: el conflicto armado en Colombia

Fernando Estrada G.*

* Profesor investigador CIPE, Universidad Externado de Colombia. Dirección electrónica: persuacion@gmail.com.

–Introduction. –I. The hypotesis. –II. What does strategic evolution mean? –III. Where are we now? –IV. Context and trajectory. –V. Strategic correlations. –VI. Evolution of the conflict. –VII. Heuristics. –VIII. Territorial expansion. –IX. Emerging bands. –X. Conclusions. –Bibliography.

Primera versión recibida el 7 de julio de 2011; versión final aceptada el 29 de julio de 2011.

RESUMEN

Este artículo propone una lectura del conflicto armado a partir de un diseño evolutivo que tenga en cuenta el concepto de agencias de protección privada en las obras de Schelling / Nozick / Gambetta. Su objetivo es evaluar la dinámica del conflicto y los cambios de la producción científica de los autores. El contexto de los conflictos, que incluye, nuevas expresiones de la violencia y el relativo fracaso de la reinserción paramilitar implica usar nuevos modelos de análisis (la argumentación, la teoría de juegos y la información inconsistente). La evolución reciente de las bandas emergentes y su expansión a zonas que eran campamentos paramilitares requiere el seguimiento no sólo del gobierno y las autoridades, sino la investigación del conflicto en la actualidad. El autor ofrece soporte a la investigación heurística de la teoría estratégica de Schelling, las agencias y la protección de Nozick y las recientes contribuciones de Gambetta a la relación entre el crimen organizado y los carteles de la droga.

Palabras clave: Guerra civil, Colombia, conflicto armado, teoría estratégica, Gambetta, Nozick, Schelling.

ABSTRACT

This article proposes a reading of the armed conflict from an evolutionary design that takes into account the concept of private protection agencies in the works of Schelling / Nozick / Gambetta. Their aim is to assess the dynamics of conflict and changes from its author's scientific output. A context of conflicts that includes new expressions of violence and the relative failure of the paramilitary reintegration involves using new analytical models (argumentation, game theory and inconsistent information). The recent evolution of emerging gangs and their expansion into areas that were paramilitary camps requires monitoring not only of the government and the authorities, but those investigating the conflict in the present tense. The author provides heuristic research support from Schelling's theory of strategy, Nozick's agencies and the protection, and Gambetta's recent contributions to the relationship between organized crime and drug cartels.

Key words: Civil War, Colombia, armed conflict, drug trafficking, organized crime, paramilitary counterinsurgency war, Game Theory and inconsistent information.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article propose une lecture du conflit armé en Colombie à partir d'une conception évolutive qui prend en compte le concept d'agences de protection privées dans les travaux de Schelling / Nozick / Gambetta, dont leur objectif est d'évaluer la dynamique des conflits et des changements. Dans unconflit qui inclut de nouvelles expressions de violence et l'échec relatif de la réinsertion des paramilitairesdans la société civile, il faut utiliser des nouveaux modèles analytiques (argumentation, théorie des jeux et des informations incohérentes). L'évolution récente de gangs émergents et leur expansion dans des zones qui étaient des camps paramilitaires, a besoin de la surveillance non seulement de la part du gouvernement et des autorités, mais également de la part de ceux qui enquêtent sur le conflit. L'auteur fournit un soutien à la recherche heuristique de la théorie de la stratégieproposée par Schelling, de la théorie des agences et la protection proposée par Nozicket des récentes contributions de Gambetta concernant la relation entre le crime organisé et les cartels de drogue.

Most clef : Guerre civile, la Colombie, conflit armé, trafic de stupéfiant, crime organicé, théorie des jeux et asymétrie d'information.

Clasificación JEL: D23, D82, D74.

Introduction

The Colombian armed conflict has evolved over the last decade. However, this evolution has not necessarily been reflected in the analyses of some researchers who have heavily influenced public opinion. The following hypotheses are the most relevant for the questions that will be raised in this article:

1. Neither an armed conflict nor a civil war exist in Colombia: the para-state groups have disarmed, and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (hereafter referred to as the FARC) and the National Liberation Army (hereafter referred to as the ELN) are being defeated (official version upheld by the Uribe government according to José Obdulio Gaviria, Posada Carbó and Alfredo Rangel1).

2. Due to their causal relationship, violence and the conflict in general have evolved in a uniform manner. As such, present examples of both can be explained using similar methods (Daniel Pecaut)2.

3. Colombian violence manifested in diverse modalities (such as homicides, crime and massacres) is derived from the armed conflict; and vice versa, the armed conflict has caused chains of civil violence and state anomie (Waldmann)3.

4. In the end, the strategies employed by the guerrillas and the paramilitaries have become analogous with regards to both their objectives and their procedures. An extended learning curb has demonstrated that their differences are minimal (Fernando Cubides, León Valencia)4. Premise: Hypotheses to be questioned concerning the armed conflict: no armed conflict, violence and armed conflict are uniform, violence is derived from armed conflict, guerrillas and paras the same,

5. The driving force behind the functionality of the para-state groups and their persistence over the last two decades has been the drugs industry. The drugs economy and other related businesses are fundamental factors in the Colombian armed conflict (Duncan, Camacho Guisado)5.

Each hypothesis expresses a predominant analytic focus on the strategic evolution of the armed conflict. It must be emphasised that this analytic classification is not meant to impose a complete taxonomy and, even less, does it intend to accredit the analysts with rigid positions. However, it is contended that to a great extent the classification does reflect both academic publications and media sources that generate public opinion. Those who believe that Colombia has consolidated a constitutional democracy with full guarantees to security and a reduction in violence during the Uribe government (1) will also share the hypothesis that the violent out lashes are nothing more than revenge and retaliations between the cartels (5). The analysts that have explained the conflict through social science categories (3) are found to have similar conclusions to those who observe regularities or small differences in the conflict over a large period of time (2). Lastly, those that identify and use economic variables to explain the conflict will uphold that there is little difference between the strategies and the military operatives of the violent actors (4) – (5). Whilst voicing their support for the Uribe government, the analysts can uphold hypotheses (1) – (4) – (5); or alternatively, they can deny the hypotheses (2) – (3).

It is obvious that with the evolution of the armed conflict the analysts could offer less superficial hypotheses than those articulated above. The armed conflict and displays of violence in Colombia are both variant and continuous in kind. Since the eighties, the drugs industry has influenced the illegal trade market including arms, smuggling and drugs; but how has this interfered with fundamental sectors of the legal market, such as real estate, tourism, transport, and less obviously with poultry sector? How does communication operate between organized crime, kidnapping, the guerrillas and the paramilitaries? To what extent has the conflict transformed living conditions in urban and rural Colombia? Unfortunately, these are questions that have failed to be addressed in the conventional interpretations of violence perpetuated after the 60s.

I. The hypotesis

In order to complement previous studies, the present article aims to balance on the one the one hand substantiated arguments, and on the other, the strategic evolution of the conflict. Taking into account limitations, the reach of the article is confined to addressing problems that have been confronted within the last decade (argumentation, strategies developed within a civil war and asymmetric information). As such, the objective is to present an analysis of the conflict and its recent evolution in the context of private security actors. It is contended that the evolutionary state of the conflict offers unprecedented aspects with respect to the violence perpetrated in the 60s and the war fought between the drugs cartels during the 80s6. Contrary to hypothesis (1), it is argued that the reinsertion of paramilitary forces as part of a Democratic Security policy has not given definitive results7. The guerrilla groups have as yet not been defeated and the reinserted paramilitaries have merely returned to their organisations (in contradiction to hypotheses (1) and (4)). The geographic makeup of the armed conflict shows dynamics of territorial competition between paramilitary groups and insurgents acting in coalition with drugs cartels [hypothesis (5)]. As a result, the evolution of the armed conflict has provided fertile ground for a private security and protection market, further demanded by a geographical and territorial transformation8.

Let us sustain that the questions relating to the continuation and evolution of the conflict over the last decade are to some extent different to those relating to its original causes and embryonic evolution addressed by the principal actors (contrary to hypothesis (2)). Taken from this perspective, the various organisations have behaved and continue to behave according to their own rationale. However, some analysts feel comfortable with characterising the paramilitaries, insurgents and criminal gangs as equivalent. This tautology does not have explanatory force. In Colombia the actors violate common expectations of normal conduct, to an implausible degree. An aspect that has received little attention in conventional literature is that the majority of those integrated in the parastate groups tend to violate a basic general principal: namely, preservation of one's own life. This applies to a lesser degree to insurgents, and even less to members of criminal organisations. This violation becomes more worrying in as much as the para-state organisations seem to break the dictates of instrumental rationality: the actors should preserve their integrity when there is a great risk posed against their life. A correlation between unemployment and illiteracy and an early intake into the criminal networks weave threads into the tapestry of the conflict and present complications for any analysis (contrary to hypothesis (5)).

In the explanatory framework of the violence perpetrated in Colombia, geography has assumed a secondary role. Research undertaken over the last decade has constructed conflict maps that only partially represent the changes that have taken place regarding para-state territorial presence. The map still does not differentiate between the unprecedented strategies advanced by the organisations, nor does it reveal the territorial confrontations between such groups. Further questions need to be addressed: How can the geography of the violence help to explain the struggle between insurgents and paramilitaries to control the dominant smuggling areas? Likewise, how can intragroup incentives explain the distribution and negotiation of territories, drugs and arms in border zone?

These questions expose the need to introduce a geographic dimension to conflict analysis. The conflict maps should address group structure and gauge possible changes. Indeed, paramilitary mobility seems to correspond to different factors to that of the anti-insurgent movement advanced by the public forces and with the support of Carlos Castaño and Salvatore Mancuso. Significantly, the war of territorial control does not seek to displace the ideological enemy, but to compete in the drugs market (hypothesis (5)). Additionally, a geographical map of the conflict ahould addresses the changing political dynamics within principal and secondary cities. A model outlining territorial competition strategies between para-state groups and conflicts within the organisations is attached in the annex.

II. What does strategic evolution mean?

According to Schelling9, conflict theories can be classified into those that see the conflict as a pathological state and study its' causes and treatment, and those that accept the conflict as a fact and analyse the behaviour which arises out of it. This last category is then divided into those theories that comprehensively analyse, in its full complexity, all those that participate in a conflict (rational and irrational conduct, caculi and motivations), and those theories that consider the actors that act rationally in a conflict (competition, generalised beneficial end and means of achieving this end).

The latter category is known as conflict strategy. This article will explore Schelling's notion of conflict strategy with relation to the Colombian conflict for three reasons: a) as analysts ourselves, we are taking a position in the conflict; therefore, we want to know for what reasons the actors rationally perpetrate violence; b) we have an interest in understanding what types of changes and phenomena the principal actors experience; c) it is possible that we have a certain degree of influence (direct and indirect) over the behaviour and the social representations that spring from the conflict, and for that reason, it is important to understand the variables which restrict possible action.

Rational conduct is the fundamental factor to be considered in this article. Indeed, Schelling's diagram suggests that conflict strategy can be understood by analysing various characteristics of rational behaviour: the micro behaviour of an individual, the miso behaviour of a soldier within an armed group or macro behaviour of the armed group in general. Individuals actions' are motivated by incentives that can be quantified, ranging from basic salary, bonuses and awards for successful operations, to goods collected for threat, extortion and blackmail. These explanatory elements can by used to construct a coherent account of the rationality for joining one of the armed forces (as observed the individual's motivation may not be violent). In any case, motivation to act is not considered in moral terms when analysing the complex structure of rationality.

Limiting conflict studies to strategy theory reduces the understanding of field of action solely to rational conduct (as opposed to irrational conduct motivated by passion); which is to say, not only to intelligent conduct, but also to conduct motivated by a utilitarian calculation of advantages and inconveniences. Within an armed group this is based on a coherent system of values, such as obedience, the benefits of lying, punishment, incentives etc. This limited perspective has its advantages: it allows for the development of a theory of conflict strategy based on rational choice.

Assuming the existence of the conflict and contending that each armed actor has to ''win'' does not necessarily imply that the actors' interests are in opposition. Only in a theoretic case of a pure conflict are the interests of the antagonists in complete opposition and the goal is total extermination of the adversary. However, coalitions of otherwise enemy armed forces may form to access economic resources, control drugs production and the main transportation routes, protect the population to gain local support, negotiate, etc. As such, competing actors have a common interest. This is especially the case in Colombia where there are a plethora of armed groups competing in a diverse geographic landscape. Therefore, a gain in the language of a conflict does not necessarily translate into gains with respect to the adversary, but gains with respect to one of the systems of values (micro, miso and macro). Within the context of a conflict, there must always the possibility of a solution. The possibility of a solution and the common interests between the various armed factions creates a mutual inter-dependence. This mutual inter-dependence allows for a diverse range of tactics, such as intimidation, threat, disarmament and negotiation, which continually change the dynamics of the conflict, specific to time and territory.

The mutual inter-dependence has a psychological element. In one region some armed factions may be friends, in another they may be foes, but in either case the various groups will never have comprehensive information concerning the others. For example, they will not know the quantity and quality of their arms, their territorial control, their resources or the size of their cultivations. Much of the information that they do receive is based on rumour. The asymmetric and incomplete information provides breeding ground for psychological warfare. Strategy does not have to refer to the use of force, but to what Schelling denominates: ''the exploitation of potential force''. Due to the lack of information concerning the other armed groups, a threatened group to some extent can only hazard a guess at whether a threat can actually be followed through. This strategy affects both the enemy and those who form part of the alliance because the aim of the strategy is to deliver a solution that is mutually beneficial for all the participants, whether that be negatively avoiding harm or positively gaining a benefit.

In terms of the game theory, the most interesting conflicts are not those which add up to zero, for example in the Cold War where the enemy forces knew that they had equal and opposite power in the form of nuclear weapons which resulted in a strategic tie, but those in which the competing factions have asymmetric and incomplete information concerning the other, and in which one side does not have to win, but both groups can simultaneously gain from a conflict through their common interests. In this study, the exploitation of potential force is understood to compare how strategies are developed within an organisation (rationality, inter-dependence, friend-enemy, means of achieving an end) and how competitive strategies (threat, intimidation, extortion, fines and taxes) between different groups are developed, in key territories.

Threatening the opposition is an important strategy. The use and style of threats has been developed in such a way that it now delivers profitable results. Time has taught that for a threat to be successful then it must be believable, and its credibility depends on the implied risks and actions to be complied with by the threatening party. As such, the efficiency of the threat depends on the rationale of the adversary. For example, the threat of mass destruction can only intimidate an enemy if first, that enemy believes that those threatening them have the capacity to mass destruct, and second, that there equally exists a possibility not to destruct. In the case of Colombia, the threatening party must be able to take preventative measures to stop the confrontations from escalating. Agreements between the government and the paramilitaries have intended to limit the capacity of the FARC and the ELN to threat and extort10.

The process through which the idea of conflict strategy has been developed has been considerable slow. The existent theory is very vague and there is little literature that applies the theory to the case study of Colombia. Methodology has not been developed concerning the use of threat and the related literature does not provide possible solutions to the immediate problems. Why has there been a lack of theoretical development? The answer lies in the fact that the military services, in contrast to almost all other important professions, lack an identifiable academic counterpart. Both the military and the interest groups fail to recognise the relevance of the problem.

What would a theory concerning conflict strategy in Colombia address? Which questions would it try to answer? Which ideas would it try to group together, clarify or communicate in a more effective manner? To start with, it would have to identify the key elements of the conflict and create a typology of the various conducts employed by the armed parties (for example the government and the para-state groups). The objective of strategy is to influence the actions of an adversary and to induce a desired behaviour, but what system of values provides for the credibility of a threat? All of these questions demonstrate that there is sufficient material to create a theory that would help to give greater understanding of the Colombian conflict. This paper will try to answer these questions and will integrate various perspectives into the analysis, such as the game theory, inconsistent information, argument analysis and collective decision-making.

According to the Conventional Game Theory, violence perpetrated in an armed conflict is rationally or irrationally motivated. Some orthodox writers believe it is exclusively one or the other. However, it is dogmatic to sustain that violence is only rationally motivated because there is no optimal level of rationality used for applying violence. Likewise, violence cannot only be motivated by passion because enemies will rationalise the best means of achieving benefits, such as drugs production, and this may involve an alliance with otherwise enemy forces. Lets say for example that soldier A is threatening the family of an enemy soldier B. B may pay soldier A not to harm his family out of fear, which is a passion, or because he rationally deduces that A always follows through with his threats. A more nuanced understanding of strategy contends that violence is both rationally and irrationally motivated, that which Schelling names an inter-dependent decision theory. There is psychological dependence between the various groups, and their actions towards each other are both rational and irrational. For example, the para-state groups use dates and facts, information and estimations concerning the enemy to strategise and the government uses expected behavioural patterns attributed to insurgents, paramilitaries and organized criminals.

The assumption that, during a conflict, strategic decisions are made using a rational framework, implicitly affirms a rational utilitarian theory of action. Many of the critical elements than are integrated into the model of rational conduct can be typified as rational or irrational. This premise obliges us to consider what irrationality means. Irrationality is defined as an incoherent and disordered system of values that may lead to miscalculations. Information systems, collective decision-making or the parameters by which the possibility of error is represented or loss of control can be considered as an intent to formalize the study of irrationality.

The apparent limitations that are imposed by starting from this premise of rationality are revealed by two observations: (a) an otherwise unstable or irrational enemy can often be intuitively understood as strategic; and (b) an explicit theory that considers rational decision-making and its strategic consequences unequivocally demonstrates that acting rationally does not necessarily constitute a universal advantage in conflict situations. Many of the factors of rationality suppose adverse factors in certain strategic situations, that is to say, it can be rational not to be rational. Additionally, there are defences that in strategy theory could be seen as deteriorations of rationality. This also demonstrates that in the face of a threat, it is not always advantageous to have an efficient system of communication, to have complete information regarding the adversary or to find oneself in the position of power to provide all and freely from one's own goods.

To resume, the focus taken in this article that addresses conflict strategy is an analytic extension of Thomas C. Schelling's work (1960). The strategy theory is conceived in relation to mutual inter-dependence. In a conflict, the behaviour of soldiers that compete for control of zones and territories with economic benefits is regarded as sufficiently rational (Collier/Skaperdas). In this article, the strategy is related to incentives and motivations: money, salaries, drugs, arms, women etc. The geography of the country reduces local populations to military or political objectives by the principal agents of the conflict. Also the strategy follows patterns of logic in terms of communication and violent discourse. Information exchanged during a war, including the use of arms, the communication of motives given for an attack or a defence, is significantly strategic (Lakoff).

III. Where are we now?

Why do in some regions in Colombia seem to have such a persistent incapacity for economic and social growth? Collective action and growth have been severely stunted by the Colombian conflict in which violence is the primary instrument. Over time, broader factors have also come into play. Regions that lie in the centre of the country, for example cities such as Bogotá and Medellín, have been significantly developed, offer broad employment opportunities and are relatively superior to regions situated in the peripheries of Colombia, such as Bojayá and Leticia11. The geography of disproportionate economic development corresponds to historical and social deviations, the importance of which has been vastly overlooked (Lora/Gaviria, 2005)12. In part, these conditions can be explained by the evolution of institutionalisation and the Colombian state, and additionally by problems in the structure of collective action and beliefs (North, 2007). Some critics have also diagnosed the problem as a lack of confidence. These precarious factors negatively affect the possibility to achieve a better quality of life in these zones that have been beaten down by the armed conflict. As has been recently noted, the lack of a capital within which the citizens can have confidence, has brought perverse effects to the whole Colombian society (Gaviria 2005)13.

However, another focus area that has been of progressive interest for many analysts is related with the reverse of the previous questions: How is it possible that citizens achieve productive activity in spite of the social order? Which aspects condition or restrain the debilitation of social order? These questions change the way that conflict studies addresses information that circulates in the form of propaganda, the news and public opinion. For many analysts, Colombia represents a laboratory of investigation: contrasting markets, an entrepreneurial society, and indicators of optimum levels of happiness in all the regions14.

It was during the 80's, more so than previous decades that the para-state groups (insurgents, self-defence groups and criminal organisations) began to offer a lucrative service: private protection. Given the vacuum left by the State and the mistrust of key organisations in economic development, these groups undertook illegal activities in various regions of the country. To start with they offered subtle mechanisms of protection at a low cost and afterwards they used intimidation. The paramilitaries and insurgents managed to integrate into local political life and in some cases their intervention exceeded basic social relations, intervening in, with or without authority, the resolution of disputes and quarrels fought amongst members of the communities15.

The protection agencies caused decisive profound changes in the territorial geography of the country that affected regional governability. As they amplified the number of their fronts in zones such as Magdelena Medio and Puerto Boyacá, they also expanded their radius of political influence in the Pacific Coast, the Guajira and up to the reaches of the south of the country in depeartments such as Cauca and Nariño. In certain towns, the policies undertaken by the para-state groups served to reduce the incident of common delinquency (Deas, 1999). Also, they planned a redistribution of contracts designed to develop public work, but the plan was never followed through with. These are examples that show that the para-state groups undermined the state whenever they deemed necessary. The vigilence that they provided gave relative calm to the citizens, also forms of social and political contract in the shadow of the state16.

This extensive global mechanism of extortion greatly exemplifies parasite forms of social contract. The self-defence forces intervened in local power, saving the appearances of a reality that reduced governability for three consecutive governments: Gaviria, Samper and Pastrana. The long-term effects have been devastating. The para-state groups used random methodology to manage high cost business transactions across various sectors and exponentially raised general mistrust. The alliances and coalitions between self-defence forces and the drugs cartels or between insurgents and landowners spoilt legitimate constitutional order and legitimate power in various regions, capital cities and intermediate towns.

An accumulation of necessities caused by unemployment or a low income in certain municipals create an abundance of potential human resources to be recruited into the para-state groups. These groups manage to recruit indolence and youth, whose age oscillates between 13 and 20 years old, into their fronts. By providing the local population with incentives aiming at satisfying their basic necessities, the selfdefence forces and the insurgents were able to get a stronghold in strategic territories where they were then able to reek fear and control the illegal markets. Within the localities, illegal mechanisms were adopted to resolve domestic disputes. Those who were favoured by the commanders were assured power for illegal business deals and transactions within and outside of their zones. This new order managed to work perfectly thanks to indulgent government employees and entities who soiled their hands in para-state activities, or merely acted dumb.

The influence that these agencies have had on collective Colombian life has been negative. The local mafias, self-defence forces, insurgents and paramilitaries have affected regional territorial structure and conditioned new cultural standards. The incentives and belief that wellbeing consists in material goods, together with an inversion of community values, profoundly undermined the affirmative conventions of work, education and collective responsibility. Progressive weakening public confidence was caused by political agreements which assured the functioning of the private security agencies and para-political intervention in government. A panorama of this magnitude was obviously going to structurally affect the institutions.

The territorial configuration of the protection agencies has left concomitant consequences. Perhaps the most alarming is the distrust that Colombian society has of the state and the coalitions that formed between the elite, organised crime and parastate groups. A broad look at the structure of the private protection agencies reveals new organisational modalities and perverse mechanism of contract. This image below shows new illegal groups and patterns of shared learning (Cubides, 2005). Additionally, the continual sequence of intracommunity conflicts has puts breaks on development initiatives and economic and social change which would otherwise be of great benefit to the populations situated in the geographic periphery of the country where these illegal armed protection agencies are prominent.

This lifestyle spread which caused unprecedented transformations in intermediate sized cities such as Pereira, Tuluá, Valledupar and Bucaramanga (where commanders and gangsters were given temporary refuge). It also contributed to increased legalisation of paramilitary activities that oiled the machinery of their alternative form of governance. The informal economy and open-door boarder smuggling fused with legal production and economy to form a dominant symbiosis. Additionally, a mutually supporting system made up of the legal and the mafioso had come to constitute a resourceful platform for those offering security. Furthermore, abandoned populations provided a fruitful pool of clientele to which protection agencies could provide their services. The choice between anarchy or protection agencies has not been considered by those who make decisions in government. Above all if those affected count on additional resources coming from business with the same protection agencies.

IV. Context and trajectory

Analysing the Colombian conflict calls for a certain degree of commitment on the part of the researchers. This occasionally creating a danger for them: too much curiosity kills. One persistent research problem is that when explaining the way that the para-state organisations operate, normally only inchoate information can be found. However, with the consolidation of the nexus between national organisms and international institutions, more valuable information has been uncovered regarding the mechanisms they employed. The confessions of the head drugs traffickers and evidence divulged in the prosecutions against members of criminal organisations in the trials lead by the attorney general also provide us with leads17.

It is possible to work from information collected from official judicial reports of the paramilitary and drugs trafficking trials. The accused is rewarded with benefits for declaring their illegal activities, crimes and the massacres that they have participated in. These confessions are valuable for our analysis. Jorge 40, Mancuso, and Don Diego, all prosecuted in the United States under charges of drugs trafficking, gave details in their confessions that paint a more complete picture of their individual front's activities and paramilitary strategy employed over the last few decades.

Generally, the sources used in recent research what are predominantly descriptive in character. However, in our case we have opted for using research initiated a decade ago, consisting in a referential mark based on argumentation theory, non-cooperative games and asymmetrical information. When argumentation techniques and rational structures are used to explain violence, it is demonstrated that the parastate organisations operated by forming coalitions in strategic territories for drugs production and trafficking. The aim of this project is to advance research of these new strands of the conflict18.

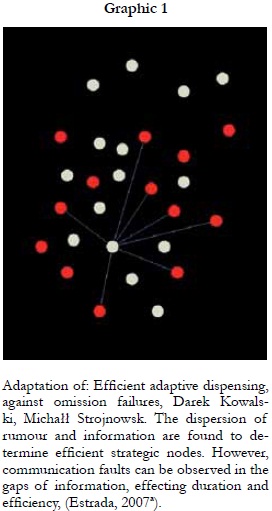

An aspect of the armed conflict which we focused our reserach on was the reconstruction of the phenomena of rumors. Kowalski's and Strojnowsk's graphic models show that the location of threatened populations can be used to explain spacial ties between the armed actors and the expansion of information (Estrada, 2007ª). Using their models, the network of information can be visualised as a natural, progressive and non-lineal expansion. The information spreads through a sequence of cuasal relationships and disperses in accordance with the force of individual and collective beliefs in a particular social network.

The relationship between information and snitching, prima facie, falls into the domain of rumours. Often people are quick to tell on their neighbours so as to obtain benefits or protection and security. The accusations take on various forms, one of these being rumour (''they say that'', ''some people are saying'', ''its been said that''). The character of a rumour allows for little alterations or discrepancies to be made as it passes from ear to ear. The consequences, even on a global scale, can be regrettable. The rumours are motivated by perverse collective and personal interests: first, the interests lie in the perks received by the informer; second, the interests relate to the strategy of terror which is used to intimidate victims and those who are close to them.

The pieces of information that correlate with rumour are not always collected within completely structured conditions. What does that mean? As such, certain pieces of potentially key information are chosen and related to strategic points of the network that are in charge of reproducing information in adjacent areas. Así, un nodo que contiene potencialmente información clave puede relacionarse con puntos estratégicos en la red que se encargaría de reproducir la información en áreas adyacentes. Explain more. Out of a collection of known information, keys pieces are chosen and related to one another so as to justify strategy. The direction that the information takes is not linear but follows capricious diversions. In other words, rumors are formed by interactive relationships and have evident faults: gaps in information, distortion and cases of individuals in a network behaving indifferently. This can be observed in the following diagram:

Even more than investigating the relationship between information and rumour affected by the armed conflict, the aim of our research was to discover the conceptual structures that underlie conflict discourse. Based on interviews and statements given by paramilitaries and insurgents (Carlos Castaño, Alfonso Cano, Comandante Gabino), reports and both printed and digital disclosed information, we were able to design cartography for the metaphors and analogies employed by the violent actors. The research made use of Lakoff 's (1999) and Facounnier's theories with application to the Colombian context19.

V. Strategic correlations

The research in this article has avoided being misguided down two common paths. First, there is a marked tendency to typify the actors as protagonists. The history of the self-defence forces and insurgents written by journalists is generally speculative in kind, characterising the criminals as Robin Hood heroes. Second, the analysis of parastate business is prejudiced because it is considered in isolation, every group being judged within different strategic systems. It is illogical to explain operational mechanisms outside of their macro contexts and not consider the holistic structure of the various organisations. These two aspects have received little attention, according [Hypothesis (4)].

During the initial stage of the Uribe government, the reinsertion programme in which various paramilitary fronts participated (which is still presently being run) was accompanied by triumphal rhetoric concerning the dawning of such criminal organisations. Many academics support Uribe's project to demobilize the irregular armies that have been the authors of numerous massacres over the last decade. Commissions of what have been organised for various purposes: to obtain financial support and respect from the international community, to create a memory for the victims, to offer reinserted soldiers employment in business and industry. Also, there was a considerable amount of media hype that covered the governmental paramilitary reinsertion project. A delirious degree of confident in the project has driven many to conclude that no armed conflict exists in Colombia [Hypothesis (1)]20.

However, reality has had a different face than the ideology. Evidence shows that the paramilitaries have been restructured and the coalitions between the drugs cartels and the emerging groups who aim to occupy territories, control illegal businesses and traffic drugs within the illicit international markets have been renewed21. Novel forms of competition have developed between the para-state groups, above all, amongst small combat units and the information systems that they use are designed to relocate rapidly when the enemy attacks. By concentrating their laboratories in smaller localities, the protection agencies and groups of drugs traffickers manage to keep the market reasonable stable22.

The expression of the emerging groups has inherited the operatives that the insurgents and paramilitaries traditionally employ: threats of the population, threatening the local governors, displacement of the nucleus of many local populations and assassination of indigenous leaders and farmers. On top of this, intelligence work and information are used to selection the target victims of the group [Hypothesis (4)]. In the relocate strategy stage, the groups escalate the war in the predominate territory. Even though the conduct of the various groups is relatively insular, they compete to offer security to those who can pay, and the rest of the population is available for extortion and threat.

As can be observed, a decreased intensity of war coincides with the increased asymmetry in relation to aggressive resources and to the defensives employed amongst the para-state groups. This makes sense, especially when the asymmetry is in the extreme, on the grounds that the groups represent only a small fraction of the population and their possibility of success in a military confrontation is abysmally low, with little probability that they take up arms. In our case, we cannot measure the form of total relationship i.e. when the combating front have equal force, it also may be the case that they are reluctant to initiate a high cost war when the probability of beneficial results is hazy. As the asymmetry grows, the strongest group may be tempted to act more oppressively and provoke a reaction. When evaluating the present stage of the conflict, we observe a difference in the increased asymmetry, which reaches a higher peak in relation to paramilitary activity.

During this time the conflict has unfolded between paramilitaries groups not fully differentiated [Hypothesis (2), (4)]. Its territorial location techniques and their means of control are integrated into a process of mutual learning. Its distance is not too pronounced. Between the lines intersect at the right end; angle reflection of their actions is small. In other words, while the odds are much against the weaker group, the feasibility of an outbreak of confrontation could be, ceteris paribus, higher among the security forces and the FARC or the ELN, which between government forces and groups emerging (paramilitary). Empirically this happened when a coalition of paramilitary's fronts found consistent with military objectives of the security forces.

In many cases the ideological allegiances or financial incentives consistently acted in favor of more resources towards combative. These could be kept temporarily. Each group provided normative conditions of recruitment, training areas, operational, wages and provisions, are fighting for exclusive loyalties especially when confrontation intensifies. In zones of territorial influence populations experiencing fears of assimilation and annihilation on the other side and excluded induced empathy shared sensibilities and beliefs. In summary, it was reasonable during the high frequency of armed conflict to find expressions of support group's para-statal's. In regions such as the Serranía de San Lucas, Magdalena Medio and the Pacific Coast, the paramilitaries reached a ''capital support'' who managed to spread among the residents, and in times of massacres led to the fronts and differentiate their businesses with more careful not to be confused with the identity of the FARC or the ELN.

VI. Evolution of the conflict

Relate para-statal groups, (AUC, paramilitaries, insurgents, criminal organizations) with a specific period of history in Colombia is common23. Conventional history, however, tend to cause violence originating in an uneven distribution of property, the feudal nature of the linkages between farmers and landowners in the late nineteenth century. A clear social and economic inequality,, which would be extended considerably with the lack of a solid political and institutional system. A distant ruling class was promoting extreme aggravation of political fanaticism that would have bipartisan violence of the 50s enduring one of its expressions.

But if the Colombian insurgents in its confrontation with the State are discursively heir to nineteenth-century wars, this trial did not have the same force in the case of irregular clusters, such as self-defense and paramilitary forces during the second half of the twentieth century. These relate to a world determined by new values: consumption, crime and demographic concentration of urban poverty. As a mixture of components that provides opportunities for those who can show more power to negotiate and offer protection in areas where land conflicts are being intensively [Hypothesis (2), (5)].

A fallacy promoted in the analysis suggests that the spiral of conflict grew so aggressive as the means employed. If during the original violence of mid-twentieth century, liberals and conservatives defended their beliefs by killing and topping, it is believed that after the 80s, vengeance and retaliation deepened thanks to the sophisticated weaponry that was bought with drug funds [Hypothesis (5)]. This interpretation is partially correct. Then as now faced by those territories and populations, also are motivated by revenge, scams, and duels of honor. Generations of violent actors who left us so-called violence to maintain their causes classical achieved within a context of more complex claims and disputes.

However, as we have emphasized, the evolution of abundant evidence against parastatal groups contrasts with few new developments in research models. The literature lacks empirical basis for effect and analytical relationships are weak. Several authors are more interested in spreading common places to relate their information sources [Hypothesis (1)].

VII. Heuristics

In the context of this nature is required to work on the subject with conceptual tools of greater density. Academic research on the phenomena described are supplemented in our perspective with the following components:

- The idea of explaining the war in Colombia taking as basis the evolution and development of private protection agencies has been linked to the progressive generation of a potential market that starts with farmers and entrepreneurs in the Middle Magdalena and Puerto Boyaca, pervades the political geography of the Pacific Coast, between smugglers and local politicians in border areas, the corridors of Urabá from investments in oil palm cultivation, the departments of the South: Caquetá and Putumayo, with vast fields of coca, and extending into the areas north of Valle, Cauca and Nariño, triggering retaliation violent organization with a tradition since the '60s24.

- Our research on private security agencies in emerging conflicts between their original sources is the work of Robert Nozick: Anarchy, State and Utopia (1974). The analytical merits of the concept are related Nozick be fully explained in the main components of private protection agencies in a market model25. Besides putting the strategic, conditions of the agencies within the evolutionary process of a political contract incomplete. The structure of competition for private protection in a society with irregular conflicts triggered an increasing spiral of further violence by their actors. The work we do has made progress in a complementary direction26.

- Another reference in the field of strategic games and logical behavior in irregular conflicts have been the work of Thomas Schelling: The Strategic of Conflict (1960) and Choise and Consecuence (1984). In both works we find ideas to understand the correlations between organized forms of crime with informal forms of the economy. A theory of indirect communication which plays a key role in cases such as threats and bribery. Successful coalitions between paramilitaries and drug cartels after 90, or links between smugglers and dealers insurgency (FARC, ELN) reflect aspects of organized crime on an original conflict between causal reasons.

- Research by Diego Gambetta on the Sicilian Mafia (2003) analytical framework partially meets Schelling / Nozick within targets relevant to the investigation of the Colombian case. We want to explore the direction taken by the work of Gambetta basically the following: (a) the idea of the protection industry as a potential markets, (b) provides comparative relationships between markets and market protection ordered disordered. The work we have elaborated on the information and rumor in conflict areas (Estrada, 2006), are complemented with the idea developed in the trademarks Gambetta and mechanisms of communication and information used by criminal organizations.

A wide variety of prejudice has gained ground among proponent's comments on links between clusters paramilitary and drug cartels [hypothesis (3), (5)]. A widely accepted belief is that the protection and security are marginal to the objectives of the armed conflict. This idea suggests a fragmented version of illegal markets in which each business unit operates independently of the others. The boss in the chain of the conflict only indirectly, since its objectives are focused on the delivery routes, money laundering or the business of smuggling at the borders. However, relations between the posters with the paramilitaries or between the cartels and the guerrillas, as well as the relationships they have minor criminal organizations with links in the chain, they agree on many goals27.

In Gambetta (2003) the case of the Sicilian Mafia that private protection is a ''central activity of a well-ordered mob. Those who receive protection may be fussy, but not usually considered useless, and many more times than you think in general, are actively seeking''. This observation in the Colombian case is given the apparent objections lawlessness among emerging groups, but some disorder in the form of business does not mean that the ways in which security operates a business does not represent high profitability. In fact it is possible to verify how the conflict with struggles over the monopoly of illegal businesses in municipalities and regions.

The reason's for this confusion is related to studies that focus on aspects of the problem prone to spectacular. The categories and core concepts to define the conflict still within a sphere comprised of platitudes. We need to go far enough with less journalistic study structures. Another bias underlines the absence of armed conflict; some analysts invoke magic solution to this formula. ''Organized Crime'', ''emerging bands'', ''guerrillas'' or ''paramilitaries'' are used as denominators to describe in many cases the same thing. The basic problem is complicated by the difficult nature found in the sources. A variety of reason's in the Colombian case requires a restructuring and work on materials that have been ''kicked by the angels'' (John L. Austin, Philosopher).

There is first the need for a separate conceptual framework for agents, organizations, cartels, suppliers and buyers of protection. And recognize that in half a century of shared activities, paramilitary groups have managed to bring an illegal market has its own dynamics among large investors. How have they affected the regional circuits of the illegal market of the customs protection of each region in Colombia: mayors, city councils, legal trade? A proper understanding of these differences also reflects a fundamental issue of political economy: how they have incorporated the private protection and illegal markets to the general structure of formal economy in Colombia [Problems controvert the assumptions (1), (2), (3), (5)].

VIII. Territorial expansion

This unit is close to problems of work within Garfinkel / Skaperdas (2007) in the sense of exploring how disputes arising from civil wars are related to defective forms of competition for economic resources. More specifically, the analysis made in the context of civil wars show a marked tendency to the formation of scale underlying business operating on property rights and an expanded private protection. The authors call this phenomenon: technologies of conflict. Our objective is similar to the extent that we also investigate the effects of the illegal market of private protection on income: the decisive aspects in the distribution of the local mafia powers or modes how a group relates paramilitary defects with marginal productivity in areas that remain in dispute. In other words it means asking how the protection operates in the informal markets depending on the intensity of competition and demand to the citizens for greater security.

The analytical framework Garfinkel / Skaperdas, has served us well to observe the mechanisms of adaptability and change with the clusters within a given territorial area. What elements of economic behavior prevalent among combat units: the commanders and regular soldiers. What incentives for capital accumulation and how specific influences may have illegal markets between those who determine market decisions. The role of governors and the sharing of political powers are dangerous. The distribution of resources in areas under pressure from paramilitaries and insurgents is akin to a hobbesian war28.

Recent research on dynamic changes of the armed conflict in Colombia has an extensive list of problems: How much has changed from political geography and territorial reintegration and delivery of paramilitary fronts?: ''In the hands of those who have been protected areas and regions and exploited by the FARC and the ELN during the Uribe government? How has recovered the State territorial presence in region to compete until recently by paramilitary and guerrilla? What is this presence of the State itself and what government policies in regions like the Pacific and the Urabá Chocó?

These questions require a look at different economic and social geography as well as an analysis of strategies that correlate between paramilitary movements (black eagles, countries, and stubble), drug cartels and guerrilla fronts. Proceed with an auxiliary hypothesis in our approach: the FARC military crossroads during the Uribe administration and the rehabilitation program of the paramilitaries has not meant the final stage of the conflict, but rather we sustain that such conditions have forced officials to change violent their operational plans and find coalitions to maintain its dominance and local political power, [contrary to Hypothesis (1), (2)].

In several recent research findings protection agencies are presented as unitary actors, strategies and objectives homogeneous territorial control unit and organizational unit. Nothing could be farther from reality. Because parastatal groups, especially during the Uribe administration have been forced to make internal adjustments in their foreheads, movements between middle and top (paramilitaries, FARC, ELN) and military coalitions in large regions of the country [Contrary to Hypothesis (5) ]. The strategic dynamics tend to differentiate their identities. New denominators semantic (black eagles) are combined with lessons learned in the field of conflict. At the same time, those affected in areas under parastatal control mechanisms seek to protect their interests and properties.

Within this scheme of territorial projections, ranchers, businessmen, landowners and merchants seek again to reduce their transaction costs. The safety and security goods returned as attractive between paramilitaries and insurgents. Throughout the past century has informally evolved a system of interconnection between paramilitaries and insurgents seeking to replace the strength and legitimacy of the state. So the interests (assets, properties, businesses, families) and the funds paid are not charged individually. Those working the supply side know what they do: associate with each other, guerrillas and paramilitaries, organized criminals and kidnappers, have entered into close relations key strategic areas of regional geography. On rare occasions the division of labor depends on specialties ranging from street robbery to the slaughter, through kidnapping and extortion.

It is likely that such a situation the individual incentives as a result of complete fragmentation affecting collective action. And the rewards of government campaign to gradually weaken the FARC. The individual reattachment act positively on the operating balance of forces although official figures for experts are exaggerated (Isaza 2009). The central questions revolve around budgets less encouraging: rearrangement insurgency, territorial division and negotiations between political actors and commanders; escalation of conflict in ascending sequence: intimidation, extortion, threats, and selective killings. One of the key issues in this scenario: how intra organizational balances established and local resource competitions between parastatal groups now replace paramilitaries and insurgents?

Research in the context of international civil wars may be promising to better observe our case. The relationship between clusters and semi-internal relations among members of an organization, as well as its geographic expansion and strategic, is central to understanding the trends of territorial conflict in Colombia. So part of our next goal is to make a partial assessment of these specific problems in the Colombian context. We'll see if the dynamics that determine changes locally specific aspects shared with other regions in the world.

IX. Emerging bands

The political disintegration of clusters paramilitaries is one of the most difficult to address. Should we say des-ideological? Take up arms against the state ''? Or use the State to ''fight those who oppose the State? This double movement triggers a misleading way of posing the problem. If politics is lost in the conflict, what are the reasons? It was argued by many analysts is that the drug trade and drug trafficking explain everything [Hypothesis (5)]. Again, this means putting everything in one basket.

And is it not so? The social have worked with differences? Mono-causal question is as flawed as its response, ceteris paribus, explanations that place within the same level: strategies, objectives, policy, armament. The need to differentiate and develop a reclassification (by regions, territories, incentives, resources and power), is essential. The changes provided in locations such as Puerto Boyacá Puerto Triunfo and after the paramilitary reintegration program are sufficient to understand that we were wrong to simplify the conflict and its resolution.

Is it the rearmament of paramilitary? Pure drugs business? Who are their leaders less ''spectacular''? Who pays? What area of political / military project? Questions whose require question's of critical geography and logical extension in the localities. The explanations are divided between those positions in emerging bands fragmented expression of common crime and organized crime, or who were concerned to rearm and consolidate in former territories of the paramilitaries. The picture is cloudy. The truth, however, is that the actions of urban crime in border towns and illegal businesses, they reveal a strategic expansion whose geography has not been studied yet.

Part of conventional geography has been used in order to divert attention from critical areas of conflict. Exploit the fears and hostility feeds. Depending on the source providing the information is abused mapping to develop interpretations. A map is presented as reality; however, the maps are not reality. It is possible that further studies of critical geography teach us, by example, not only in what regions or areas of the country there is expansion of emerging bands, but to contribute to better define the dynamics of transition and learning the paramilitaries groups. If paramilitary gangs are emerging should be able to expose what updates or changes its projections territorial behavior and strategic29.

The disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR) of the paramilitaries, have you failed? Being negative response, what explains the return of member's combatants to areas that were predominantly paramilitary? There are many concerns expressed serious institutional difficulties to handle a problem of dimensions that transcend the boundaries of government. However, in the Colombian case, the gaps in the program seem to respond to original conceptions of the process with severe limitations. Veterans do not surrender all their weapons. Businessmen, traders and, in general, economic sectors gave no support to the expectations of employment and occupation. And gradually the incentives of the program have been giving their way to new demands and proposals on the protection market. The negative influence of these factors, coupled with retaliation and crimes of ex-playing elements that deserve consideration [argument to be against the hypothesis (1)].

If government policy is to confuse emerging drug gangs, there are reasons to test their hypotheses. The emerging bands, it is claimed, do not have a counter-ideology that separates the paramilitaries. The paramilitary groups that were formed and evolved from Puerto Boyacá during the '80s, until the fronts of the Calima Bloc, dominant in the Pacific region, ''were organized around a program counter? It is not clear. First, because their structures are not preserved uniformity of command (each front emerged and responded to specific demands of those who financed their creation). Second, its members did not share resources from a single supplier. Third, their statements and not ideologically conceived. The ''paramilitary ideology'' was really more an artifact30.

Some works have explored the relationship between paramilitary groups and regional powers31. Documentation found in computer files and papers (bills, notes or receipts book) makes a clear influence on contracting mechanisms, and resource transfers and municipal departments.

Injected capital flows to regional economies by drug traffickers were protected by the warlords32.

X. Conclusions

Far from being ordered in accordance with strategic plans of a single organization, emerging bands have become increasingly common, despite the hostility caused by the Uribe administration and the propaganda against [Hypothesis (1), (5)] has proved devastatingly effective. The ideology that mobilizes its actions in regions such as Córdoba, Cauca, Valle, Nariño and La Guajira, not politics, not even be described as a counterinsurgency strategy, but rather a specific narrative of unmet basic needs. It is possible to believe that in conditions of desperate unemployment, for example, will become an effective policy33.

This interpretation of suffering violence will shake if focuses on a guilty (the State) which in turn can isolate the causes of violence casually addressing the problem. These narrative units are offered as a means of justifying causes quite far from their origins. The emerging bands, paramilitary, guerrilla and criminal organizations have enough speech in favor of its strategic objectives. If suffering is seen as natural or without cause shall be considered a misfortune instead of injustice and produce resignation rather than rebellion. Therefore, mafia, guerrillas or paramilitaries claimed its causes in speeches that seek to prosecute, rather than assuming the status of perpetrators.

It happened with the FARC from its origins in Marquetalia, with the AUC of Magdalena Medio, with the MAS (Death to Kidnappers), with the paramilitaries in Cordoba and Antioquia Urabá, with paramilitaries under Ramon Isaza and the Black Eagles under the command of Don Mario, every one of the main actors of the conflict is delivered to a discourse of guilt. Interpret the actions of their enemies as crimes, inserting an all-encompassing discourse on monstrosity of his actions. Outreach campaigns and territorial dominance, population displacement and destruction in the regions should be observed also by creating a myth that will help sustain the conspiracy.

Demonizing its enemies and responsible for the atrocities of the war not only helped to neutralize the scruples to kill peasants and Indians ( ''guerrillas dressed in civilian clothes,'' said Jorge 40 and Carlos Castaño). He allegedly also helped intensify recruitment for their cause. If the regions where groups did not operate in a limited way-orwith a legitimate presence of state agencies, the opportunity was unique to invoke the need for his presence, and the discipline imposed on populations. The enemy was seen as a destroyer of peaceful coexistence, the state as indifferent and insulated to the center. This was the condensation of their ideology. But the causes alleged hidden interest in the discourse of higher crime and criminal scope.

The ideology had abdicated her political identity. Shares of emerging bands seem to be defined instrumentally by the drug economy and the dominance of strategic geography. The recruitment of youth and adolescents preferably made in depressed areas of Bogota, Medellin, Cali, Bucaramanga and Barranquilla, basically show that the conviction is not doctrinaire. For some emerging rescue their unemployment and poverty, incorporating the main workforce at little risk. We have passed since the violence of the 60s classic, low imperatives disguised by the discourse of the Cold War, into a product of the first decade of the century, where conflicts of interest between groups paramilitaries, is reduced to the drug markets and drug trafficking [hypothesis (5)].

What we sought in this review of research on the conflict in Colombia is to hire our work with some of the assumptions most influential among the public. In no way were completed articles or books released in the last decade, nor in his fullness we have examined the authors dealing with conflict. The hypothesis we have proposed as predominant versions, have been outlined leaving out details that do not affect the whole. In the introduction we said that these are not caricatures, but strongly held belief among those who put their theories about the Colombian conflict.

We show, contrary to the hypothesis (1), which indeed we have reason to be wary of rumors about the end of armed conflict and the final dismantling of paramilitary groups. The facts of war are striking and show us that the FARC, though diminished in their action, remain structurally intact. And the paramilitaries were able to sell at a relatively low price the idea of reintegration, in fact, maintained camps Vicente Castaño and rear with new heads of emerging bands (Don Mario, stubble). The armed conflict in Colombia has taken on new faces, like Clausewitz's metaphor.

An explanation of the armed conflict [Hypothesis (2), (3)] has been complemented in our approach from a theory of the Schelling strategy / Nozick. We believe that addressing the conflict from the strategies and territorial geography promises less simple observations. New wars do not necessarily mean radical breaks with the strategy of violent actors of the 60s, but no doubt that incorporate aspects such as drug trafficking and smuggling, are variables whose explanation is more complex. Game theory and asymmetric information and discourse analysis contribute substantially to improved research methods.

There are sufficient aspects of analogy. Analyst in the strategy and operations of guerrillas and paramilitaries, have suggested that the Colombian conflict analysis should show the differences between clusters paramilitary. Not only because after the 80s, drug trafficking has played a decisive role, but because the geography of territories and control combinations have not been studied sufficiently. Geography of armed conflict should also provide tools to understand the impact of war on natural resources, for example. Our approach is complementary to the hypothesis (4) of the introduction.

Finally, we sustain that while the drug economy has filtered the structure of semi-groups, promoting market competition and private security protection, drug trafficking does not explain absolutely all sources of violence in Colombia. The strategy of armed conflict has its main actors incentives are deeply rooted in unequal economic relations. There differences between regions in the center and the periphery of the Colombia and asymmetrical forms of development, poverty, unemployment and corruption. These are variables in which the drug is not directly involved but are part of historical attitudes that require our analysis.

Bibliography

1. Angrist, J. and Kugler, A. (2008). ''Rural Windfall or a New Resource Curse Coca, Income, and Civil Conflict in Colombia'', The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. XC may, number 2. [ Links ]

2. Banks, C. and Sokolowski, J. (2008). From War on Drugs to War against Terrorism: Modeling the Evolution of Colombia's Counter-Insurgency, Social Science Research. [ Links ]

3. Caja s, J. (2008). ''Globalización del crimen, cultura y mercados ilegales'', Ide@s, Concyteg, Año 3, Núm. 36. [ Links ]

4. Castillo, M. (2009). ''La decisión de desplazarse: un modelo teórico a partir de un estudio de caso'', Bogotá, Revista Análisis Político 65, Enero/Abril, Instituto de Estudios Políticos y Relaciones Internacionales, IEPRI, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, pp. 33-52. [ Links ]

5. Comisión Nacional de Reparación y Reconciliación (2007). Disidentes, rearmados y emergentes: ¿bandas criminales o tercera generación paramilitar?, Bogotá; Grupos armados emergentes en Colombia, Fundación Seguridad & Democracia, pp. 21. [ Links ]

6. Cubides, F. (1999). ''Los paramilitares y su estrategia'' en Malcom Deas / María Victoria Llorente, Reconocer la guerra para construir la paz, Bogotá, Norma, Cerec, Uniandes, pp. 151-199. [ Links ]

7. Cubides, F. (2005). Burocracias armadas, Bogotá, Editorial Norma, pp. 200. [ Links ]

8. Deas, M. (1999), Intercambios violentos, reflexiones sobre la violencia en Colombia, Bogotá, Taurus, pp. 113. [ Links ]

9. Echandía, C. Dos décadas de escalamiento del conflict armado en Colombia, 1986-2006. Universidad Externado de Colombia, pp. 309. [ Links ]

10. Estrada, F. [coautor], (2002). Terrorismo y seguridad, Editorial Planeta / Revista Semana, Bogotá. [ Links ]

11. Estrada, F. [coautor], (2003). Laberintos de Paz, Bucaramanga, Funprocep. [ Links ]

12. Estrada, F. (2004). Las metáforas de una guerra perpetua. Pragmática de la argumentación en el conflicto armado en Colombia, Fondo Editorial Universidad Eafit, pág. 178. [ Links ]

13. Estrada, F. (2006). ''Estado Mínimo, Agencia de Protección y Control Territorial'', Revista Análisis Político, Vol. 56, pp. 115-131, IEPRI, Bogotá, Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Colombia. [ Links ]

14. Estrada, F. (2006). Los Nombres del Leviatán, Análisis de discursos de la Guerra en Colombia, Revista Semana. [ Links ]

15. Estrada, F. (2007a). ''La información y el rumor en zonas de conflicto, estrategias por el poder local en la confrontación armada en Colombia'', Revista Análisis Político, IEPRI, Vol. 60, pp. 44-59. [ Links ]

16. Fauconnier, G. (2000). Mappings in Thought and Language, Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

17. Fals, O.; Guzmán, G. y Umaña, E. La violencia en Colombia, Bogotá, Taurus, pp, 488. [ Links ]

18. Franco, V. y Restrepo, J. (2007). ''Dinámica reciente de la reorganización paramilitar'', Bogotá, Cinep, pp. 33. [ Links ]

19. Gambetta, D. (1993). The Sicilian Mafia, the Business of Private Protection, Harvard College. [ Links ]

20. Garfinkel, M. (2004a). ''Stable alliance formation in distributional conflict'', European Journal of Political Economy 20, pp. 829-852. [ Links ]

21. Garfinkel, M. (2004b). ''On the stable formation of groups: Managing the conflict within''. Conflict Management and Peace Science 21, pp. 43-68. [ Links ]

22. Garfinkel, M. & Skaperdas, S. (2007). ''Economics of Conflict: An Overview'', Handbook of Defense Economics, Volume 2, Edited by Todd Sandler and Keith Hartley. [ Links ]

23. Gaviria, A. & Lora, E. (2003). Depende el porvenir de la geografía? Enseñanzas de América Latina, Alfaomega / Banco Interamenricano de Desarrollo, pp.192. [ Links ]

24. Gaviria, A. (2005). Del romanticismo al realismo social, Bogotá, Editorial Norma, pp. 214. [ Links ]

25. Hoffman, M. (2000). ''Emerging combatants, war crimes and the future of international humanitarian law'', Crime, Law & Social Change 34, pp. 99-110. [ Links ]

26. Hoyos, D. (2009). ''Dinámicas político-electorales en zonas de influencia paramilitar. Análisis de la competencia y la participación electoral'', Bogotá, Revista Análisis Político 65, Instituto de Estudios Políticos y Relaciones Internacionales, IEPRI, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, pp. 13-32. [ Links ]

27. Isaza, J. & Campos, D. (2009). ''Consideraciones cuantitativas sobre la evolución reciente del conflicto'', Bogotá, Revista Análisis Político 65, Instituto de Estudios Políticos y Relaciones Internacionales, IEPRI, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, pp. 3-12. [ Links ]

28. Kalmanovitz, S. (2001), Las instituciones y el desarrollo económico en Colombia, Bogotá, Editorial Norma, pp. 304. [ Links ]

29. Lakoff , G. (1999). Philosophy in the Flesh, the embodied mind and its challenge to Western Thought, con Mark Johnson. Basic Books, New York. [ Links ]

30. León G. Eduardo Pizarro, (1991). Las Farc (1949-1965).De la autodefensa a la combinación de todas las formas de lucha, con la colaboración de Ricardo Peñaranda Instituto de Estudios Políticos y Relaciones Internacionales de la Universidad Nacional. Tercer Mundo Editores, Bogotá. [ Links ]

31. León G, Eduardo Pizarro, (2004). Una democracia asediada. Balance y perspectivas del conflicto armado en Colombia, Bogotá, Grupo Editorial Norma, pp. 370. [ Links ]

32. López, A. (2008). El cartel de los sapos, la historia secreta de las mafias del narcotráfico más poderosas del mundo: el cartel del norte del valle, Bogotá, Planeta. [ Links ]

33. Mejía, D. (2005). ''The War Against Drug Producers'', with H. Grossman, NBER Working Paper, No. 11141. [ Links ]

34. Mejía D. ''Capital Destruction, Optimal Defense and Economic Growth'', with C.E. Posada, Borradores de Economía, No. 257 (working paper), Banco de la República. [ Links ]

35. North, D. (2007). Para entender el proceso de cambio económico, Bogotá, Editorial Norma, pp. 261. [ Links ]

36. Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, State and Utopia, Basic Books, (edición del FCE, Anarquía, Estado y Utopía, 1978). [ Links ]

37. Ocampo, J. (2007). Historia económica de Colombia, Bogotá, Planeta. [ Links ]

38. Pecaut, D. (2008). Las Farc, ¿Una guerrilla sin fin o sin fines?, Bogotá, Editorial Norma. [ Links ]

39. Rangel, A. (1998). Colombia, guerra en el fin de siglo, Bogotá, TM Editores, Universidad de los Andes, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales. [ Links ]

40. Reyes, A. (2009). Guerreros y campesinos. El despojo de la tierra en Colombia, Bogotá, Editorial Norma. [ Links ]

41. Roldán, M. (2003). A sangre y fuego. La violencia en Antioquia, 1946-1953, Bogotá, Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia, Banco de la República, pp. 435. [ Links ]

42. Schelling, T. (1960). The Strategic of Conflict, Harvard University Press, (Edición castellana, La Estrategia del Conflicto, Madrid, Editorial Tecnos, 1964). [ Links ]

43. Schelling, T. (1984). Choice and Consequence, Harvard University Press, pp. 379. [ Links ]

44. Uribe, M. (1990). Matar, rematar y contramatar, Las masacres de la violencia en el Tolima, 1948-1964, Bogotá, Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular, pp. 209. [ Links ]

45. Valencia, L. (2009). Mis años en la Guerra, Bogotá, Editorial Norma, pp. 288. [ Links ]

46. Wärneryd, K. (2003). ''Informationin conflicts'': Journal of Economic Theory, 110, pp. 121-136. [ Links ]

NOTAS

1 José Obdulio Gaviria, Sofismas del terrorismo en Colombia, Bogotá, Editorial Planeta, 2005; Posada Carbó, Eduardo, La nación soñada, Bogotá, Editorial Norma, 2006, pp. 388; even though less dogmatic than the former in his public position though less dogmatic, the reports and columns of the jouranlist, Alfredo Rangel, have echoed in the Uribe government: ''Long Live Plan Colombia'' (Semana, 21/03/2009); ''Alan Jara's absentmindedness'' (Semana, 21/02/2009); ''What did the FARC last agree on?'' (Semana, 16/03/2008. Rangel has had a reactionary tendency over the last decade and has defended economic sectors that have recieved benefits under the Uribe government.

2 Daniel Pecaut argues for this hypothesis in his famous article, The past, present and future of the violence: ''The violence has become a functional mode of society, given the birth of diverse networks that exert influence over the population and of official regulations. It is better not to analyse the violence as a provional reality. This all suggests that a durable situation has been created, Revista Análisis Político, 30, 1997, IEPRI, Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

3 Peter Waldmann, Guerra civil, terrorismo y anomia, Bogotá, Editorial Norma, 2007, pp. 304. Waldmann's position reflects a varient interpretation supported by analists whose sources are limited to opinion. This does not constitute an extensive critic of Waldmann's work in general, but the observations concerning Colombia are seen as forced so as to support his hypothesis. The magazine, Revista Análisis Político, has also published the article The habilitualization of violence in Colombia 32, sep/dec. 1997.

4 Fernando Cubides has reviewed the fundamental differences in strategy employed by the paramilitaries and the insurgents, and in particular he has focused on the use of intimidation and mutual learning, please see: Burocracias armadas, Bogotá, Editorial Norma, p. 200; also please see León Valencia's report: Parapolítica, la ruta de la expansión paramilitar y los acuerdos políticos, Bogotá, Corporación Nuevo Arco Iris, 2007, p. 396.