Introduction

Violence is understood by the World Health Organization as the intentional use of physical force or power, real or threatened, against oneself, against another person, or against a group or community that either results in or has a possibility of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, developmental disability or deprivation 1.

Nowadays, violence against women is a target of concern for public health in Brazil and worldwide 2,3, since many are victims of violence within the family and, in most situations, that violence is perpetrated by someone they live with every day 2,4,5.

The number of cases involving women who are victims of aggression but fail to take any decision due to fear and/or lack of information is significant 5. This problem tends to affect the nuclear family and causes a disruption in its organization 6,7.

According to one study, 1.5 to 5.3 million women per year report having been physically or sexually victimized by their male partners at some time in their life 8.

The so-called “Maria da Penha” Law, enacted in 2006 in Brazil, defines physical violence as any action that jeopardizes a woman’s integrity or physical health, being characterized as any action, omission or suffering of a sexual, physical, psychological and bodily, property or moral nature that occurs within the family or home. The same law defines moral violence as an action that involves injury, defamation or libel. It defines psychological violence as any action that causes emotional damage or decreased self-esteem and well-being. Finally, it defines sexual violence as any action that causes embarrassment and the performance of sexual intercourse without consent or through coercion and/or physical strength 9.

Domestic violence has been the subject of many studies around the world, both for its various forms of expression and for the consequences for those involved. It is regarded as a trans-generational and interactional phenomenon 10.

Following a study conducted by the Pan American Health Organization in collaboration with the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), a report was produced that highlights sexual violence against women as being widespread throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, which is where the survey data was collected. It is noteworthy that between 17% and 53% of the women interviewed reported having suffered physical or sexual violence perpetrated by an intimate partner 11.

The intervention of health services plays a fundamental role for women in situations of violence and ensures their human rights, given that most of these victims have contact with some type of health service at some point, even for reasons other than those related to aggression. This contact is necessary to identify violence and requires maximum attention from health professionals 12.

One study found that a significant number of health professionals believe issues related to violence are closely linked to the field of justice and security, and they are fearful of getting involved with issues or even calls of this nature 13. It is also observed that some health professionals who provide assistance to victims of violence are not adequately prepared for this type of care and experience a psychic discomfort due to the feelings of powerlessness and frustration that are generated during such care 14.

Thus, in order to subsidize the reflection on violence suffered by women, we decided to conduct this study aimed at identifying the contribution of developed research to a biopsychosocial sphere of women victims of violence and the meaning attributed to these experiences in their lives.

Method

An exploratory study was done, featuring a systematic review conducted through a critical analysis of the articles. A rigorous review was planned to summarize original research, highlighting the relevant research questions. A clear method was used to identify, select, describe the quality, collect data and analyze the studies.

The research began by asking a guiding question: “What literature has brought about social representations of women victims of violence?”

National and international databases were used to search and select the articles: LILACS (Latin American Center and Information Caribbean Health Sciences) and Pubmed (Public Medline). These articles were published between the year 2009 and June 2015.

Instrument for a systematic review

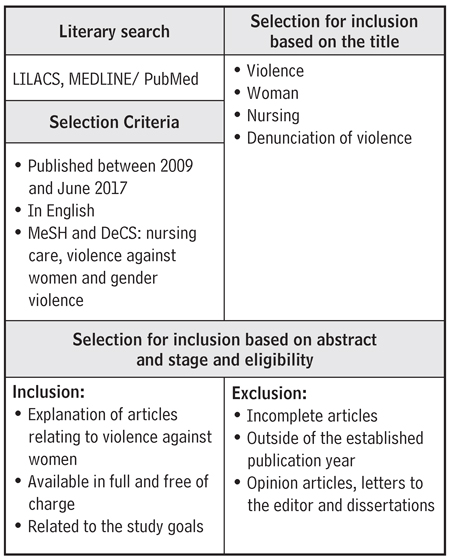

The methodological tool used in the evaluation of scientific papers was PRISMA 15. It was used for the systematic review, so as to ensure quality and make this type of study clear 16.

Identification and classification

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to select the articles. These criteria certify the accuracy and reliability of the study.

Eligibility

The selection was determined by reading the articles obtained by two reviewers, who performed a rigorous analysis based on pre-established inclusion criteria (Table 1).

Results

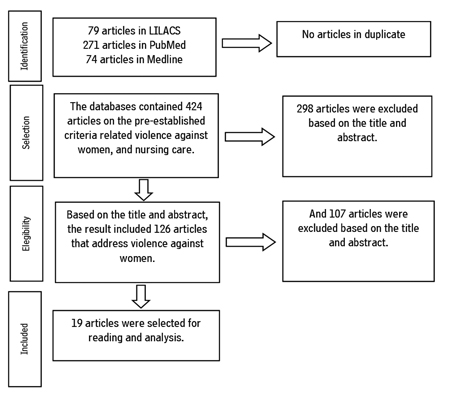

The selection of articles in the first filter turned up 66 in LILACS (Latin American Center and Information Caribbean Health Sciences), 42 in PubMed (Public Medline), and 74 in Medline (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online). Articles that do not fit the theme, are not available full, and are outside the established publication period were excluded. In all, there were 164. After reading and analyzing the articles, 18 remained (Figure 1).

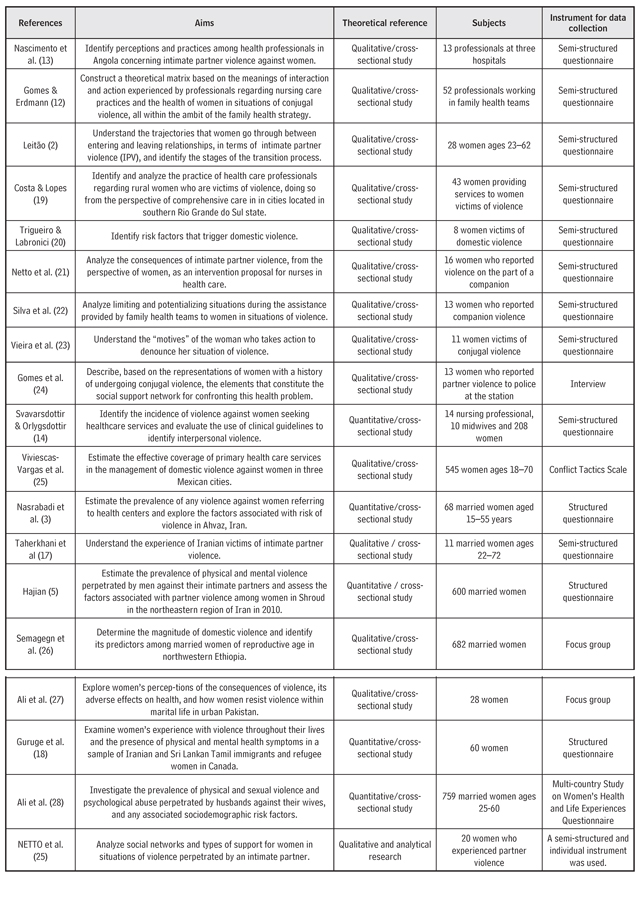

An analysis of the 19 selected studies showed that four of them used a quantitative approach, thirteen used a qualitative approach, and one study used a quantitative/qualitative approach. Among the studies with a qualitative approach, one used the phenomenological theoretical framework developed by Alfred Schütz.

The most frequent descriptors were: Domestic violence/Violence against Women/Intimate partner violence/Women’s health. As for data collection, semi-structured questionnaires were used in nine studies and structured interviews in three. There were two focus groups, while two studies used the Conflict Tactics Scale and the Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Life Experiences Questionnaire, both of which are validated instruments. One study based data collection on an interview.

In terms of age groups, the respondents were between 15 and 72 years old. Six of the studies addressed only domestic violence; five addressed domestic violence; four dealt with physical and psychological violence, and three focused on sexual violence. Table 2 shows some of the data analyzed.

As to the objectives set out by the authors of the selected studies, one of the prime ones is the concern to seek scientific answers to everyday issues that permeate the difficulty and the current challenges in health to serving these women. Thus, some studies have sought to identify what motivates women to not report their abusers, with a focus on different angles; namely, through a reflection on the biopsychosocial aspects involved, the context in which cases of violence occur, the reasons that lead women to file a complaint, and even the perceptions of health professionals who serve these women.

The results of this review were classified into two categories: meanings of the experience of violence endured by women and reasons to break the cycle of violence.

Meanings of the experience of violence endured by women: Out of the 18 studies selected for this review, twelve contemplated the question of the meaning of the experience of violence endured by women, whether in the household or in the care of a health service 12,17. Feelings of uncertainty, fear and submission were noted, and some women reported increased anxiety, insecurity, a greater number of nightmares, and feelings of panic 18. Violence against women is felt by them as cultural privatization and symbolic; one laid the blame on those who fail to do anything. Other no less worrying feelings, though on a smaller scale, also involved socio-political and health actions, namely: anger, pain, shame, feelings of anguish and abandonment, low self-esteem, helplessness, grief, desire to break off the relationship with the partner, depression, sadness, loneliness, and suicidal thoughts, among others 5,7. To be treated at the hospital has added a sense of embarrassment to the problem these women face, a feeling of discomfort at needing to present their case 17.

The denial and lack of comprehensive care perceived by women are often the result of professionals who are unprepared to deal with their own values and beliefs on the subject. This can trigger many feelings that will reflect on or impact the meaning women who have been raped will give to this experience. The service providedinvolves technicalities that prevent a humanized approach, specifically one that seeks sensitive listening and a dialogue between user and professional in search of a close relationship to establish trust for adequate care 14-21.

Recognition of disorganization in customer service is evidenced as one of the impediments to developing the provision of assistance, as was the difficulty in identifying and treating the silence victims displayed during consultation, so as to confirm suspicions of violence 13.

Reasons related to perpetuation or a break in the cycle of violence. The most cited are socioeconomic factors (unemployment or fear of losing their jobs); domestic violence (sexual, physical and psychological coercion perpetrated by intimate partners and family); the difficulty in accessing services to file a complaint; fear of death; fear of the family or fear of disappointing the family; and the desire not to abandon the children and their home. In relation to breaking the cycle of violence, the women identified despair at changes in the offender’s behavior; a desire for freedom and control of one’s own life; and a yearning for a definitive separation from their companion, among other less cited reasons.

When asked about the forms of psychological aggression suffered, the most cited were: insults, verbal threats and intimidating looks, and external communication deprivation, either through verbal or electronic means 3,5,22.

Psychological abuse was identified as a factor triggering physical aggression, because it usually is the primary act of an individual who intends to offend a woman.

In terms of physical violence, types of aggression such as slaps, kicks and jerks, intentional burns, use of a weapon or fire and property damage are the most common means adopted by the aggressor 3,5. There are also sexual violence situations where the woman is forced to have sex with her partner against her will or to perform unconventional sex acts 5,22,23.

The submission that many women adopt for cultural reasons is also identified as a triggering factor in the perpetuation of violence 26.

Most women omit the violence suffered because there is the hope the abuser’s feelings will prevail, thereby overcoming the situation, and the apologies and promises he made will be genuine 2. This mutes the problem and results in a situation where the relationship is maintained, all of which complicates making a decision.

In an effort to break this situation, some women report their attacker, demonstrating an attitude of non-compliance with the isolated or successive acts of violence they have suffered. The complaint is characterized as a way to disclose their rejection of a situation that has become progressively unsustainable 26.

The review showed evidence that the school has no direct relationship to violence. However, it did show that women living in situations of violence while unmarried tend to continue being abused even after being married. What changes in this condition is the aggressor.

Discussion

There was a consensus among the authors of the study that the production of scientific knowledge on the subject of violence against women represents a guiding principle for health policy by applying science to the concerns of those who use health services and await humanized action in this universe of biopsychosocial needs.

When observing the list of feelings triggered in women who are victims of violence, one sees a gap in the image created by common thinking in the sense that women who are caught in this cycle are devoid of feelings and are happy to live this way.

Anger and anguish, which appeared in five studies 3,5,7,29, imply that living in these conditions requires attention to a woman’s emotional state, which is commonly overlooked. It is known that most of them neglect to get the health care they require, which means the act and the aggressor end up being subdued and the woman’s real needs are neglected.

This silence on the part of the victim must be respected as a need to understand what has occurred and the need for emotional reorganization. However, it should not blind the health professional into believing the woman wanted to be raped.

The definition given by women with respect to violence as being “an experience permeated by great humiliation” reinforces this as a public health problem that requires important action, starting with the way women are treated when seeking services 13. The denial and lack of comprehensive care that often occur at the hands of unprepared professionals who do not know how to deal with their own values and beliefs on the subject can trigger many feelings that will have an impact on the meaning the raped woman will give this experience, especially when the situation at the local hospital is uncomfortable and embarrassing 25. This leads to anger, pain, shame and feelings of anguish and abandonment, among others.

Services provided in a highly technical way prevent a humanized approach, which seeks sensitive listening and a dialogue between the user and the professional in search of a closer relationship that results in trust for adequate care 6,19. Empowering women victims of violence by their silence shows a lack of understanding of the conditions concerning their right to free will.

The reception they receive in dimensional spheres has proven to be quite effective, since it is extremely important that a woman who is a victim of violence feels welcomed and understood in the face of her traumatic experience. It is necessary to create a relationship between the professional and the patient in order to discover other possible forms of violence experienced. It is noticeably easier to approach these women when trust is established 24.

Recognition of disorganization in customer service is evidenced as one of the impediments to providing assistance, as is the difficulty in identifying and treating the silence displayed by victims during the consultation, which requires further evaluation to confirm any suspicion 13.

The use of counseling, and the implementation of strategies and prevention for these abused women guarantees better care, thus allowing their quality of life to benefit. It is possible to emphasize that women who suffer physical or verbal violence feel the need to expose their feelings and it is in this context that health professionals should seek improvements in the way these victims are received 1. It is essential that these professionals use caution, not only when observing the complaints presented by the patient, but also in terms of detecting the signs and symptoms displayed during the service that is provided 6,19.

As the initial treatment afforded to these victims commonly occurs in primary care services, these are clearly potential, local instances for identifying cases of violence, especially of the domestic variety, because women suffering from this type of violence seek health services more often 29.

The nurse needs to provide holistic care in order to support a woman who is a victim of aggression. This implies knowing how to deal with the patient and, after reception, trying to understand what has happened to her. The woman should be advised to denounce her aggressor or to seek help from institutions that also deal with women who have experienced or gone through situations like the one she has endured 13.

Activities such as group meetings where women have an opportunity to report their experiences and to share their stories can be used as a time to rethink solutions to their problems. They also offer an opportunity to start a new life in society 24.

Conclusion

The violence women routinely face disrupts their biopsychosocial appearance and has consequences that last for a long time. The results obtained in this study reveal the indispensability of hosting, support, empathy, professional training for multidisciplinary teams or individual professionals, and a willingness to help women who are affected by violence, regardless of how that assistance is rendered or of the form it takes.

Understanding the biopsychosocial aspects of abused women has yet to receive much attention from researchers, but was explored to some degree during the search for articles for this review.

This study shows the fragility of the assistance being provided to women who are victims of violence. The analysis of the studies selected here demonstrates that not all health professionals who are confronted with these situations are prepared to approach them correctly or know how to direct these victims towards the most appropriate form of behavior in response to violence.

The need to expand the knowledge of health professionals who work directly with these situations is a point to be considered.

There is also the need to understand the magnitude of the difficulty of breaking this cycle of violence and the socio-demographic situations in which women are inserted that have a direct effect on their choices.