Introduction

The adolescent pregnancy (AP) rate in Brazil is higher than worldwide. Between 2010 and 2015, according to data from the Pan American Health Organization, for which adolescence comprises the age group of 15 to 29 years, the global rate of AP was 46 per 1,000 girls.

The AP can negatively impact the health of the mother and child, in addition to presenting obstetric complications. However, it cannot be classified as risky for the biomedical aspect alone, but also due to all biopsychosocial factors involved. It is a consensus that AP deserves special consideration to preserve maternal, fetal and neonatal health 2-10.

Lower socio-economic conditions associated with difficult access to services and adequate information contribute to the problem 2-10. To develop ways to face this phenomenon, we believe that nurses have an essential role, since they are at strategic places at all levels of health care. Also, they are not only present in specific health services, but also in other environments in which adolescents live, especially the school. The qualified nurse has the potential to be a reference professional in the defense of youth-friendly practices 11,12.

To create a corpus of knowledge that serves as a basis for the work of nurses and other professionals, it is crucial that Nursing is engaged in the production of scientific evidence on adolescent health and, particularly, on AP. This way, this review article aimed at verifying the state-of-the-art related to the theme, to identify, in the national and international scientific literature, the evidence produced by Nursing that provides subsidies to prevent teenage pregnancy, considering the worldwide relevance of the phenomenon and the need to implement varied approach measures.

Material and method

An integrative literature review based on the methodological recommendations of the Prisma Statement 13. It was accomplished following the steps of identification of the reports; removal of duplicates; selection of articles after reading the title and abstract; selection of reports after reading the full text; final selection of reports after critical analysis 13.

To answer the objective, according to the PICO strategy (the acronym for Patient, Intervention, Comparison and Outcomes 14) the following research question was addressed: What are the scientific national and international publications by Nursing that offers subsidies to prevent teenage pregnancy?

The searches were carried out in the following metabases: Public/PublisherMedline (PubMed), Virtual Health Library (BVS), Scopus, and Web of Science, the latter two through the Periodic Portal of the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brazil. Searches were also carried out in the Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (Lilacs) and Nursing data (BDEnf). The selection of studies involved the combination of the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: “Nursing” (AND) “Prevention and control” (AND) “adolescence pregnancy”; in addition to the Descritores em Ciências da Saúde (DeCS) “enfermagem” (AND) “prevenção e controle” (AND) “gravidez na adolescência”.

The research included original articles from experimental, descriptive or analytical, quantitative and qualitative studies, available in full, in Portuguese, English and Spanish languages, carried out fully or partially by nurses, published from January 2013 to March 2020, and that answered the research question, confirming the scientific national and international publications by Nursing that offers subsidies to prevent teenage pregnancy. Thus, review articles, editorials, dissertations, theses, experience reports and other textual types that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded.

Initially, the articles were evaluated based on the title and abstract, if there were any doubts about the type of the study or its adequacy to the inclusion criteria, full reading was performed. These procedures were carried out by two researchers independently, with a comparison of the results at the end, to assure greater quality to the review. After the selection, the data from the articles were entered into a form with the following items: Identification, objective, methodological procedures, main results, and conclusions.

After formulating the research question, searching and extracting data from the articles, the following steps of the process proceeded: Categorization of the studies found, based on their main results and contributions; critical evaluation of studies; interpretation of results, identifying the main conclusions and implications from the integrative review; elaboration of the review summary, with a description of all steps performed, and presentation of the analysis results 15. The data are shown with emphasis on the main results of the articles and the thematic categories were discussed with other authors.

Results

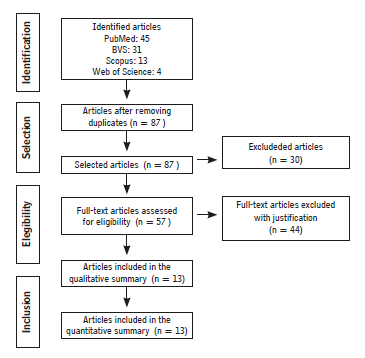

Initially, 122 articles were found and, of these, 35 were excluded due to duplication. Of the 87 remaining articles, 30 were excluded because the full text was not available. After reading the title, abstract and the authors’ profile, 41 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria in the research and, after reading them in full, another three were also excluded. The selection totaled 13 articles (Figure 1).

Source: Own elaboration.

Figure 1 Flowchart of selected articles that compose the integrative review for the period from January 2013 to March 2020

Among the selected articles, the studies were carried out in Ghana (n = 1), South Africa (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), Brazil (n = 2) and the United States of America (n = 8). Ten studies were developed by nurses alone and three studies counted on the participation of professionals from medical school or public health. Brazilian studies were available in Portuguese and English, the other studies, only in the English language.

In Table 1, the list of selected articles with the corresponding code, the authorship, the journal, the study design, the level of evidence and the main results are presented. The citations of the articles that make up the results of this review are followed by the study code, consisting of the letter “S”, for study, and the corresponding order number, established according to the year of publication, from the most recent to the oldest.

Table 1 List of studies with authorship, journal, study design, level of evidence and main results, in the PubMed, BVS, Scopus, Web of Science, BEDEnf and Lilacs metabases and databases, from January 2013 to March 2020

| Reference | Journal | Study design/level of evidence | Main results |

| S1 - Yakubu I, Garmaroudi G, Sadeghi R, Tol A, Yekaninejad MS, Yidana A (2019) 22 | Reproductive Health | Randomized clinical trial/level of evidence: 1 | Educational intervention, based on the Health Belief Model, with female adolescents reduced the sexual activity of adolescents in the short term and improved their knowledge about pregnancy prevention. |

| S2 - Madlala ST, Sibiya MN, Nqxongo TSP (2018) 21 | African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine | Qualitative study/level of evidence: 3 | Sex information exchanged with friends, digital media and magazines. Women’s responsibility for knowledge about reproduction. |

| S3 - Bersamim M, Pachall MJ, Fisher D (2018) 27 | The Journal of School Nursing | Cross-sectional quantitative/level of evidence: 4 | Adolescents in school health centers are more likely to have healthy sexual behaviors and use contraceptives. |

| S4 - Grigsby SR (2018) 19 | The Journal of School Nursing | Qualitative study/level of evidence: 3 | Participants reported relying on faith, values and personal experiences to dialogue with their daughters about sex. |

| S5 - Daley AM, Polifroni C (2018) 28 | The Journal of School Nursing | Qualitative study/level of evidence: 3 | School health centers are ideal places to address or minimize barriers to contraceptive care for adolescents once they are accessible and offer confidentiality. However, some services have restrictions. |

| S6 - Chernick LS, Stockwell MS, Wu M, Castaño PM, Schnall R, Westhoff CL et al. (2017) 23 | Journal of Adolescent Health | Randomized clinical trial/level of evidence: 1 | Younger adolescents responded better to the intervention. They believe that the greatest indifference among older adolescents was because of the previous contact with the shared information. |

| S7 - Harris AL (2016) 16 | Journal of Pediatric Nursing | Cross-sectional quantitative/level of evidence: 4 | Communication between parents and children about sex prevailed between mothers and children. The higher educational level of parents did not influence the results. |

| S8 - Hoare KJ, Decker E (2016) 26 | Collegian | Qualitative study/level of evidence: 3 | The intervention was well-received in the study due to its discretion and a positive approach to sexuality. |

| S9 - Child GD, Knight C, White R (2015) 20 | Journal of Pediatric Nursing | Qualitative study/level of evidence: 3 | Condom use and sexual abstention as measures to prevent pregnancy. To be successful in their academic and sports activities was a desire that surpassed that of having sex or becoming pregnant. |

| S10 - Serowoky ML, George N, Yarandi H (2015) 25 | Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing | Cohort study/level of evidence: 3 | High satisfaction with the program, which achieved 95.8 % adhesion. Improvement of knowledge related to the prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and AP, besides attitudes and intentions directed to the use of condoms and a decrease in the plan to have sex. |

| S11 - Ferreira EB, Veras JLA, Brito AS, Gomes EA, Mendes JPA, Aquino JM (2014) 17 | Revista de pesquisa: cuidado é fundamental (on-line) | Cross-sectional quantitative/level of evidence: 4 | Participants were mostly brown, Catholic, and were in a domestic partnership and had low family income. They demonstrated knowledge of the main methods, with emphasis on the latex condom and the hormonal oral contraceptive. |

| S12 - Sieving Re, McRee AL, Secor-Turner M, Garwick AW, Bearinger LH, Beckman KJ et al. (2014) 24 | Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health | Randomized clinical trial/level of evidence: 1 | The decrease in risky sexual behaviors, relational aggression and victimization by violence. |

| S13 - Assis MR, Silva LR da, Pinho AM, Moraes LEO, Lemos A (2013) 18 | Revista de Enfermagem UFPE on-line | Qualitative study/level of evidence: 3 | Sexarche between 13 and 15 years. They did not use condoms nor other methods. Sexual intercourse was shown to be influenced by social, cultural, economic and gender variables. |

Source: Own elaboration.

As for the general aspects of the objectives, we found that 46.1 % (n = 6) of the studies concerned factors associated with AP. Two studies with a quantitative approach and cross-sectional design (S4, S7), and two qualitative studies (S11, S13) describe possible causes, knowledge about contraceptive methods and communication between parents and children about sex 16-19. Two other qualitative studies explored opinions and perceptions, one of them (S9) with female adolescents, never pregnant before, about pregnancy and its consequences for the adolescent’s life 20; another (S2), with young men on AP 21.

The other studies, 38.5 % (n = 5), focused on interventions; there were three (S1, S6, S12) randomized clinical trials 22-24, one (S10) cohort study 25 to evaluate the effectiveness of a previous randomized clinical trial and one (S8) qualitative “grounded theory” study 26. In general, all studies carried out based on interventions were aimed at expanding knowledge about contraceptive methods, pregnancy, Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs), changes in behavior and lowering AP rates 23-26.

Finally, the other studies, 15.4 % (n = 2), evaluated, from the perspective of adolescents and nurses, the effectiveness of school health centers, an American model of health care for this population. A study with a quantitative approach and a cross-sectional study (S3) evaluated the impact of the school health center on the sexual health of adolescents; another (S5) addressed, through a phenomenological study, the experience of nurses in such centers 27,28.

We found that the studies contribute with important scientific knowledge related to the theme, highlighting social, cultural, family, and interventional aspects in the face of related problems. Also, although the majority (77 %) was carried out exclusively by nurses, we realized that the knowledge produced is of interest to the entire academic community and society in general.

Discussion

The studies found contribute essentially to the understanding of the current panorama of nurses’ publications on the AP theme. This shows us the trend of the studies and the points of greatest international relevance since it is a global problem 1. The data found are categorized as shown below.

Lower socioeconomic conditions

In the Brazilian studies (S11, S13), among the adolescents participating in the research and who had high-risk factors for pregnancy, or who were mothers already, they often had brown skin, were Catholic, were in a domestic partnership or marriage, had low education and low income; and sometimes, reported the desire to become pregnant 18,24.

Other authors found similar data: Low education was associated with the desire to become pregnant; also, among some low-income adolescents, becoming a mother may represent an increase in the social status, However, the occurrence of pregnancy and the fact of being a mother in a context of low education and low income are factors that perpetuate poverty and other socioeconomic and educational problems 29-31.

Also, women with education opportunities are more likely to increase their self-esteem, empowerment, and motivation to avoid early pregnancy. In Addition, they could discuss aspects related to pregnancy, with conscious decisions and protective behaviors 29.

Strongly confirming the issue of low education and other socioeconomic problems, a study showed that the children of adolescent mothers may have a deficient cognitive development, including a significant decline in the intelligence quotient, which leads to a greater need for adequate stimuli for the neurological and educational development 32. Besides, the recurrence of AP in the population is also associated with school dropout, low education and low income 33,34.

Although, domestic partnership or marriage is relevant in Brazilian studies, in other countries, the variable “marital status” can be observed differently. In Japan, a prospective study found that “single” marital status was the most frequent among women who underwent AP 35.

The North American descriptive studies (S7 and S9) of this review focused on the Black and Latin population, since the AP rates in these populations are high when compared to the white population (16, 20). Such data, added to other similar data when talking about STIs, were also observed by other authors 34,36.

The African study (S2) showed that lower socioeconomic conditions can lead to unsafe sexual intercourse, to relieve the stress of everyday life. Besides, receiving social assistance due to pregnancy was an advantage, which leads some to wish to have children to have the right to earn such benefit 21. Young people in precarious social conditions, often victims of intimidation, violence, alcohol and other drugs, among other problems, tend to neglect risks and significantly expose themselves to AP and STIs 37.

Knowledge, attitudes and cultural aspects

Among the participants in the studies that make up this review, knowledge about the main contraceptive methods was observed, with a greater emphasis on latex condoms and oral hormone pills, however, adolescents themselves reported not using them regularly due to neglect or for the desire to become pregnant; sexual abstinence until marriage was cited as a possible way to avoid unwanted pregnancies (S2, S9, S11) (21, 20, 17). However, the cultural practice of the withdrawal method was also mentioned, which contributes to the risk of AP and STIs (S2) 21.

Sexarche, the first sexual intercourse, addressed in one of the qualitative studies (S13) with girls, occurred more frequently between 13 and 15 years of age; despite this, most of the partners of these adolescent women were adults and, in general, did not use condoms or other methods. Sexual intercourse was shown to be influenced by social, cultural, economic and gender variables, in addition to the emotional immaturity of adolescents 18.

A study based on data from the 2016 National School Health Survey, conducted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, confirms the early sexual initiation of school adolescents in Brazil, with an average age of 13.2 years; moreover, among the adolescents who had already started their sexual life, 63% were male 38.

In another qualitative study (S9), concerning the opinions of the adolescents, no benefits associated with being a pregnant adolescent were observed, on the contrary, they noticed many negative consequences. They believed that being pregnant as a teenager would negatively affect their education, sporting opportunities and relationships with their parents and friends. To be successful in academic and sports activities was a desire that surpassed that of having sex or becoming pregnant 20.

Another study has already shown that adolescents may be aware of the need for contraceptive methods, however they do not have the necessary knowledge and clarification for their use, although they use them. The need to articulate actions within the scope of public health, school and family policies is evident, to provide access to health services and information 39.

The African qualitative study (S2) showed that pressure from friends was also a major factor for sexual intercourse; it is a need to confirm the status of being a man, considering the transition to adult life. African elders in the studied context, with a very important cultural role, encourage young people to be abstemious until marriage, however, the focus of this strategy is on girls. Besides, these young people recognized their responsibility in relationships, but they believe that knowledge about reproductive health is a female domain 21.

This result shows us the importance of discussing gender in the context of adolescent relationships, risk behaviors are highly influenced by gender relations, based on the heteronormative pattern, that is, with male dominance. Culturally, boys are highly motivated towards dating and sexual intercourse, almost a necessity, while girls must protect themselves: it is up to the woman to be responsible and bear the consequences of her actions 40-43.

Another element regarding cultural aspects that deserves attention is child marriage, present in some countries. Avoiding such an event implies the prevention of early pregnancies, because, besides suffering from the marriage determined by the family, these girls are under pressure to have children 29,44,45. Child/adolescent marriage is a problem recognized by international institutions, which recommends reproving it due to the influence on AP indicators and the negative repercussions for the woman’s life 1.

In turn, it has already been demonstrated that motherhood can also be a protective factor for adolescents who experience the drug phenomenon, because becoming a mother filled an emotional void that they tried to fill with drug use. For these young women, motherhood represented salvation, since they were motivated to resist the craving of drugs to become better people and to think about a different future for their children 46-48.

Sex education and specialized services

Discussing sex education was taboo, regardless of family configuration (concerning paternal presence). As sources of information, participants pointed to the important role of elders in the initiation of men into adult life and as a way to fill the gap left by families in the context of sexual education; however, the subject remains a taboo in this context 21.

It has been shown that dialogue between parents and children (male) about sex predominated between mother and children, regardless of demographic context. Despite the lower rates of communication between the father and the children, when considered together, parents (father and mother) from the suburban area showed greater communication about sex with the children than the parents from the urban area. Although the higher educational level of the parents did not interfere in the results (S7) 16, their influence on the adolescents’ perception of AP was prominent (S9) 20.

One of our studies (S4) was concerned with describing factors that influence the dialogue between mothers and daughters about sexual and reproductive health and found that the participating mothers were based on faith, personal values and personal experiences in this communication process. Thus, from these conceptions, they pass on to their daughters, values related to life and femininity. They even mention great difficulty and embarrassment in talking about some issues, with emphasis on sexual intercourse between people of the same sex and oral sex. However, they recognize that communication must happen early, in an appropriate way for each age 19.

The studies in this review address the importance of intervention in the sexual education actions of adolescents, to intervene in the condition of vulnerability concerning early pregnancy, preventing its incidence 17.

Five studies aimed at reporting interventions or evaluating their results; two, to know aspects related to services aimed at school adolescents.

The first study (S1) carried out an educational intervention guided by the Health Belief Model, which works on aspects related to the perceived susceptibility and severity regarding AP, as well as the possible consequences and benefits of postponing pregnancy. The participants showed greater knowledge related to preventing pregnancy and reducing sexual intercourse due to intentional abstinence 22.

The second study (S6) was developed from text messages sent to the phones of a group of female adolescents. The action proved to be suitable and with high acceptance; nevertheless, it was not unanimous, and contraceptive initiation was limited. They found that the younger the participants, the better the results of the intervention 23.

The third study (S10) focused on a development program for adolescents, in which the participants demonstrated high satisfaction, with 95.8% adherence. Thus, they identified an improvement in knowledge related to STIs and AP, besides to attitudes and intentions directed to condom use, as well as a decrease in the intention to have sex 25.

The fourth study (S12) found reductions in risky sexual behaviors, aggressive relationships and victimization by violence. It is believed that such findings are also due to a youth development intervention. Besides, the increase in enrollments in post-secondary education and the intrapersonal skills identified at a given follow-up stage suggest that the intervention has been able to promote healthy behaviors 24.

The fifth study (S8) evaluated the effectiveness of an intervention based on the delivery of an information flyer in a discreet way, through a strategy called “teabag”, in which an information flyer on sexuality was placed in a teabag and handed out when teenagers went on school vacation. Such a measure was taken after observing an increase in AP numbers when the adolescents returned to classes. From the perspective of adolescents, the brochure promoted empowerment, since the approach used was positive, recognizing the active sexual life of those adolescents, promoting safe sex and approving communication between partners 26.

One of the studies (S3) that addressed the initiative of school health centers found an association between their existence and healthy sexual behaviors of adolescents, as well as the use of contraceptives, especially among adolescents with lower socioeconomic conditions and in services where there is prescribing and dispensing contraceptives 27.

At the same time, another study (S5) on the same theme found that nurses consider the school health center as an ideal place for coping and minimizing barriers to contraceptive care for adolescents, as long as they are accessible and offer confidentiality. However, they find difficulties related to the availability of contraceptives and restrictions regarding confidentiality of care and the adolescent’s freedom to use the service, since parents can restrict access 28.

Interventions for the prevention of teenage pregnancy should include actions based on evidence from the community, with the involvement of leaders and social setups, the training of the people involved, technical assistance whenever necessary, access to services, the association between health and school services, the quality of care offered and the emphasis on communities in greatest need. Such interventions take time and joint effort 49,33.

Ideally, holistic programs integrated with adult life preparation should be developed, especially in more conservative societies 37. Programs to change habits and behaviors have shown potential for adherence by adolescents, not only for safe behaviors, but also for abstinence; such programs are essential if the rates of AP and STIs are high 50.

Interventions, initiatives or programs cannot be carried out in the same way for different audiences; instead, local norms, gender relations, family structures, cultural context, religious values, speeches shared by young people and other aspects of reality need to be recognized, so that the educational model undertaken is shown pertinent to those teenagers. Through such care, there is a greater chance of success 41,51.

Special attention should be given to adolescents who use alcohol or other substances, since programs or projects aimed at sex education can achieve positive effects, despite natural resistance. However, they must be persistent and constant in the challenge of having safe sexual behaviors. Once again, integrated actions should be emphasized with a view to the holistic development of this adolescent. In this sense, it is necessary to implement a continuous, planned and monitored educational process that addresses both AP and STIs and the use of psychoactive substances 52.

Despite the realities of the suburbs, frequent and quality communication about sexuality, gender and safe behaviors, between parents and children, and at school with the participation of teachers, is a crucial factor in promoting safe behaviors in the sexual practice of adolescents. However, parents are not always prepared to guide their children properly; therefore, it is necessary that parents also receive guidelines that expand their knowledge and help them to break possible barriers 53.

Men since adolescence must be also involved in actions to know the health needs of adolescents or to promote sexual and reproductive health in this population. The approach of boys is essential not only for health promotion, but also for the development of responsible parenthood in the future 54.

Adolescent pregnant women or those at higher risk of becoming pregnant, as well as their partners, must be assisted both from the perspective of vulnerability and that of resilience, with work aimed at developing skills that allow them to seek and find the necessary social, economic and cultural contribution to their conditions. Adolescents are active social agents who not only suffer from the environmental conditions in which they live, but who can also change their realities at home and in the community 55.

Conclusions

Nurses in different countries have cooperated to build knowledge about adolescent health and AP. Studies have shown that the AP problem is strongly associated with poverty and other socio-economic issues, in addition to being influenced by structural aspects such as the offer and access to health services, as well as adequate information for adolescents. Gender relations, dialogue about sex education in the family and other cultural aspects were present in the discussions, which shows its influence on this phenomenon.

We observed that most of the studies were concerned with addressing AP from a female perspective, with the recruitment of only female adolescents, which happened in 77% of the studies. One of the issues to fight in society is the accountability for subjects related to sexuality only over women; in this sense, we consider it extremely important to involve male adolescents in future studies and actions that aim to promote safe behaviors regarding sex.

Likewise, we realized that the studies did not address adolescents in schools or private health institutions, which shows a knowledge gap about these people, a fact that deserves attention, since AP can also be observed in the population of these contexts.

Education on sexual and reproductive health proved to be a path to be followed to face the problem of AP, as well as other events associated with sexuality. It was also evident that this measure should be implemented as soon as possible in the lives of adolescents, so that they have access to adequate information and assume healthy behaviors. Besides to the sexual practice itself, other aspects of life are related to unwanted outcomes for adolescence, such as sexual and gender violence, low self-esteem and substance abuse.

For these reasons, the presence of a nurse who performs holistic work in the environments attended by adolescents, jointly with other professionals, can be a great aspect to promote adolescent health and reduce teenage pregnancy rates. Nursing needs to take charge and show the importance of their role in the adolescent’s health and well-being.

Finally, considering the proposal of this work to identify subsidies to prevent AP among national and international publications by Nursing, we recognize as a limitation the small number of studies with male adolescents and the failure to approach populations with different socio-economic conditions.