Introduction

Chronic noncommunicable diseases (CNCDs) are the leading cause of hospitalization and mortality events worldwide, causing 41 million deaths each year, accounting for 74% of all deaths globally. Each year, 17 million people die from CNCDs before they reach the age of 70, and 86% of “premature” deaths occur in low- and middle- income countries. These diseases are driven by factors such as fast unplanned urbanization, the spread of unhealthy lifestyles, and population aging 1.

CNCDs encompass a range of conditions, such as heart diseases, lung diseases, cancer, and neurological disorders, with each having unique symptomatology and treatment options. Flaws in the healthcare system, limited information available about the diseases, low socioeconomic status, and advanced age are determining factors that alter the process of effective coping 2. CNCDs represent a unique process for individuals, their families, and family caregivers, which causes physical, psychological, social, and spiritual alterations and affects the quality of life of individuals who have to live with these conditions 3.

The care of a chronically ill person is provided by the person him/herself, the caregiver, and the family group 4, even though caregiving generates stress, due to the health condition 5 and the behavioral problems of the ill person 6-8. The informal caregiver provides care and tends to the needs of the affected person 9, who is unable to take care of him/herself 10, adapting to these conditions to improve the health and well-being of his/her loved one. The permanent concern for the state of health of the recipient, the need to provide physical and emotional care, and the incessant uncertainty about the progress of the disease 11, generate burdens and affect the family and social roles 12.

Over time, informal caregivers have been referred to as “hidden victims or patients” 10, because the efforts of the therapeutic plan are emphasized toward the person who is ill, ignoring the welfare and care tasks that they perform the entire time. These caregivers are not recognized as an integral axis by the healthcare system but instead are excluded and minimized, and their presence goes unnoticed by the healthcare team, ignoring their needs and concerns 13.

The caregiving role has been historically attributed to women, irrespective of their choice 14; likewise, the decisions made internally in the family to assign the role of caregiver are usually made by women, who assume the role motivated more by a feeling of obligation than by their own volition 15. Caregiving is considered an inherent part of the female role, based on a sexist social conception that perpetuates the male figure as superior and dominant over women 3,16.

On the other hand, it has been found that men also assume the caregiving role, although not at the same rate as women 17, although this number is rising and will continue to increase in the coming years, due to social and demographic trends 18. Bhan, in a study with a sample of 28,611 informal adult caregivers aged 18 and older from five countries, found that in 41.01 % of the cases, it was men who assumed this role 19.

The care provided by men is influenced by the social stigma that is exerted on their masculine identity 20,21 and affected by gender norms and stereotypes regarding the fulfillment of their role. Traditionally, society has constructed a male role with traits of independence, competence, and the ability to protect and provide for the household 22. This has led to the establishment of ingrained gender stereotypes, which generate judgment when men assume the role of caregiver 23.

Social pressure on male caregivers may lead them to question their male role fulfillment, questioning whether caring for someone else is an appropriate activity for a man and whether their social value will be affected by this role 24. Understanding how men approach caregiving, the coping mechanisms they employ, and how caregiving influences their identity and sense of self are still unclear 25, compared to the knowledge available regarding women as caregivers 26-32.

The literature has shown that assuming the role of informal caregiver, for both men and women, leads to long-term complications in quality of life, depressive symptoms, and dissatisfaction with life 33-35. Caregiving is largely determined by gender, which confers meaning to the experience of being an informal caregiver, to the point that how they approach, share tasks and structure coping strategies are influenced by this condition 36. To reduce the challenges, healthcare services must improve formal care for caregivers, to increase their perception of control, well-being, and long-term satisfaction 37.

Finally, the approach adopted by the present study is justified to contribute to the scientific evidence available on informal caregivers 38, synthesizing and analyzing the characteristics of the care provided by the men and women who assume this role. Likewise, the main objective of this work is to identify, through scientific evidence, the meaning of the experience of informal caregivers, for both men and women, of chronically ill people.

Materials and Methods

An integrative review was carried out through the following stages: identification of the problem and guiding question; literature search and definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria; data evaluation, and data analysis and presentation 39.

Initially, the theme was identified to define the guiding question: What is the meaning of the experience of informal caregivers, from a male-female perspective, when becoming responsible for the care of a chronically ill person?

Subsequently, the literature search was performed and the parameters for study selection were established. The inclusion criteria were scientific articles published in databases, with a publication date restriction of no more than eleven years, available in Spanish, English, and Portuguese; articles screened for the subareas of psychology, medicine, nursing, and health; studies with a qualitative approach and full-text type, where the caregiver’s gender can be found in the reports described.

The exclusion criteria were duplicate articles, articles with a quantitative approach (meta-analysis, mixed, RE-AIM); articles that presented the phenomenon of interest for the research but did not explicitly indicate the caregivers’ gender, and any study from the gray literature without publication in scientific Journals.

The search for articles was conducted in November and December 2021 and August 2023 in the following databases: Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science, Ovid, and PubMed Central. The following health science descriptors were used: Caregivers; Non-communicable Disease Life Change Events; Caregiver Burden; Qualitative Research; and the AND and OR boolean operators were used, respectively. The selection process of the primary studies and inclusion in the final sample followed the steps suggested by the PRISMA 2020 statement for integrative literature reviews 40.

In the next stage, all the partial results of the databases were categorized, discarding the articles whose titles, abstracts, and keywords failed to comply with the proposed research theme 41. This stage was carried out independently by the three authors, with each one filling out a database in the Excel software. After individual identification, the data were submitted together for analysis. The articles whose theme corresponded to the research were selected to be read thoroughly, critically, and independently by all the authors.

The next stage consisted of a critical reading of the selected articles with the contributions proposed by Pizarro 42, establishing the specific variables for the full reading. In addition, the methodological evaluation of qualitative rigor was carried out through the Spanish Critical Reading Skills Program (CASPe) form 43.

The variables used for critical reading of the articles, and extraction and synthesis of results were the following: authors, article title, objective, method, results, country, year, and CASPe evaluation. For the evaluation of qualitative rigor using the CASPe form, no articles were included with a score lower than or equal to 7 points.

For the results interpretation stage, the articles included in the final sample of the study were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s methodological proposal 44, which includes five consecutive stages: data familiarization, initial code generation, theme search, theme definition and naming, and report preparation. This process was carried out jointly by all the authors of the study.

The aforementioned methodology offers thematic analysis as an analytical and qualitative procedure that allows results to emerge in four themes: losses and limitations due to the caregiver’s role, feelings experienced by the caregiver, caring as an act of love, and transcendence of care (between spirituality and religiosity). The research results were presented in a manuscript with the knowledge synthesis.

Results

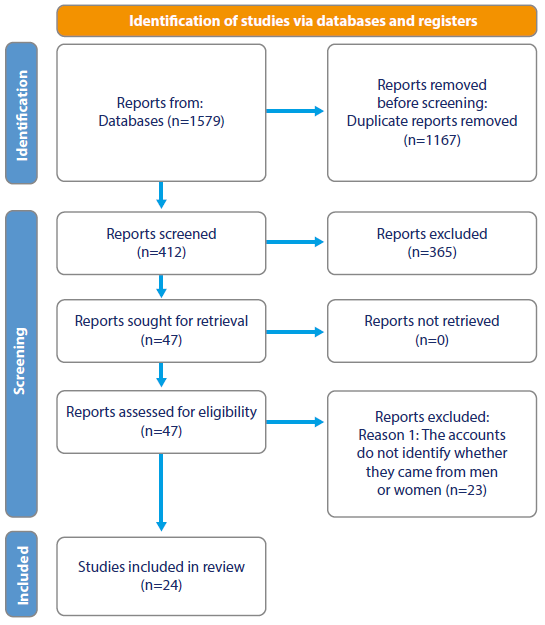

A total of 360 primary articles were identified, of which 24 remained after the selection process. The selection stages are described in Figure 1.

The articles in the final sample came from different countries, with 5 from Sweden (20.8 %); 4 from Iran (16.7 %); 3 from the United States of America, Brazil, and Australia (12.5 % respectively); and 1 each from Chile, South Korea, Norway, China, Italy, and India (4.1 % respectively). All of them were published in English; regarding the original databases, 13 were indexed in CINAHL (54.2 %) and 11 in Scopus (45.8 %).

Table 1 lists the 24 articles included that met the criteria for the development of the integrative review.

Table 1 Studies Included

| No. | Database | Authors | English study title | Vancouver Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Scopus | Steber AW Skubik-Peplaski C. Causey-Upton R. Custer M. | The Impact of Stroke Care on the Leisure Time Activities of Women Caregivers | 45 |

| 2 | Scopus | Débora Ester Grandón Valenzuela | What is Personal is Political: A Feminist Analysis of Informal Caregivers’ Daily Experience with Adult Dependents in Santiago, Chile | 46 |

| 3 | Scopus | Masoumeh Hashemi Ghasemabadi Fariba Taleghani Shahnaz Kohan Alireza Yousefy | Living Under a Cloud of Threat: The Experience of Iranian Female Caregivers with a First-Degree Relative with Breast Cancer | 47 |

| 4 | Scopus | Oliveira S.G Quintana A.M Denardin-Budó M.L Luce-Kruse M.H Garcia R.P Wünsch S Sartor S.F | Social Representations of Caregivers of Terminally Ill Patients at Home: The Family Caregiver’s Perspective | 48 |

| 5 | Scopus | Kyle L. Bower Candace L. Kemp Elisabeth O. Burgess Jaye L. Atkinson | Complexity of Care: Stressors and Strengths Among Low-Income, Mother-Daughter Dyads | 49 |

| 6 | Scopus | Nildete Pereira Gomes Larissa Chaves Pedreira Nadirlene Pereira Gomes Elaine de Oliveira Souza Fonseca Luciana Araújo dos Reis Alice de Andrade Santos | Support for Elderly Caregivers of Dependent Family Members | 50 |

| 7 | Scopus | Eriksson H Sandberg J. Hellström I. | Experiences of Long-Term Home Care as an Informal Caregiver of a Spouse: The Meanings of Gender in the Daily Lives of Caregivers | 51 |

| 8 | Scopus | Lopez V. Copp G. Molassiotis A. | Male Caregivers of Breast and Gynecologic Cancer Patients | 52 |

| 9 | Scopus | Linda Rykkje Oscar Tranvåg | Home Care for a Wife with Dementia: Elderly Husbands’ Experiences in Managing the Challenges of Daily Life | 53 |

| 10 | CINAHL | Janze Anna Henriksson Anette | The Preparation for Palliative Care as a Transition in Death Awareness: The Experiences of Family Caregivers | 54 |

| 11 | CINAHL | Zhang Jingjun Lee Diana Tze Fan | The Meaning in Family Care for Stroke in China: A Phenomenological Study | 55 |

| 12 | CINAHL | Alcimar Marcelo do Couto Edna Aparecida Barbosa de Castro Célia Pereira Caldas | The Experience of Being a Family Caregiver of Elderly Dependents in the Home Setting | 56 |

| 13 | CINAHL | Rabiei Leili Islami Ahmad Ali Abedi HeidarAli Masoudi Reza Sharifirad Gholam Reza | Caregiving in an Environment of Uncertainty: Caregivers’ Perspectives and Experiences with People Undergoing Hemodialysis in Iran | 57 |

| 14 | CINAHL | Wennerberg Mia MT Eriksson Mónica Danielson Ella Lundgren Solveig M. | Unraveling the Generalized Resilience Resources of Swedish Informal Caregivers | 58 |

| 15 | CINAHL | Paillard-Borg Stéphanie Strömberg Lars | The Importance of Reciprocity for Women Caregivers in a Super-Aged Society: A Qualitative Journalistic Approach | 59 |

| 16 | CINAHL | Petruzzo Antonio Paturzo Marco Naletto Mónica Cohen Marlene Z Álvaro Rosaria Vellone Hércules | The Lived Experience of Caregivers of People with Heart Failure: A Phenomenological Study | 60 |

| 17 | CINAHL | Bruce Isabel Lilja Catrina Sundin Karin | Mothers’ Lived Experiences of Caring for Young Children with Congenital Heart Disease | 61 |

| 18 | CINAHL | Ali Meshkinyazd Abbas Heydari Mohammadreza Fayyazi | Caregivers’ Lived Experiences with Borderline Personality Disorder Patients: A Phenomenological Study | 62 |

| 19 | CINAHL | Shukla, Shrivridhi McCoyd, Judith L. M. | A Phenomenology of Informal HIV/AIDS Care in India: Exploring Women’s Search for Authoritative Knowledge, self-Efficacy, and Resilience | 63 |

| 20 | CINAHL | Sarris, Aspa Augoustinos, Martha Williams, Nicole Ferguson, Brooke | Care Work: Caregivers’ Experiences and Needs in Australia | 64 |

| 21 | CINAHL | McDougall, Emma O’Connor, Moira Howell, Joel | “Something that happens at home and stays at home”: An Investigation of Young Caregivers’ Lived Experience in Western Australia | 65 |

| 22 | CINAHL | Meyer, Jennie Cullough, Joanne Mc Berggren, Ingela | A Phenomenological Study on Living with a Dementia-Afflicted Partner | 66 |

| 23 | Scopus | Hong S.-C Coogle CL | Marital Care for a Spouse with Dementia: A Review of the Deductive Literature Proving the Gender Perspective of Calasantis’s Work Regarding Care | 67 |

| 24 | Scopus | Sahar Malmir Hassan Navipour Reza Negarandeh | Exploring the Challenges Faced by Iranian Family Caregivers of Elderly People with Multiple Chronic Diseases: A Qualitative Research Study | 68 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the research results.

Analysis

The results were analyzed according to the following thematic categorization.

Losses and Limitations Due to the Caregiver Role

It was found that informal caregivers, both men and women, frequently highlighted the loss of direction in their own lives, the loss of leisure time, and the loss and disruption of their life projects. Both men and women highlighted physical fatigue and emotional stress as the main causes of caregiving overload 45-66,68,69.

Female caregivers reported both the feeling of loss of control of their lives and the absence of time for themselves, noting that they were unable to choose activities they would like to do due to their caregiving tasks, and thus felt the absence of independence as a loss of freedom that negatively impacted the plans they had for their own lives. They described that they had only a small circle of friends and their social relationships had been limited to a minimum, given that special meetings or events took place in most cases in their own homes, without going too far away from the person in their care 45-51,55-59,61-64,66,68.

The caregivers stated that caregiving was assumed as a daily work routine, as an unpaid job, “something” they had to do and did not expect, understanding caregiving as a challenging task, based on the concepts of strength and endurance, and conferring it a semblance of normality to feel less guilty. In most reports, they emphasize that they miss their old jobs, the way they supported their households, their conversations with friends, solving problems outside of their homes, their financial capacity, and that future projects had been lost 48,52-55,57,58,60,62,64-66,68,69.

Feelings Experienced by the Caregiver

It was found that the feeling of “permanent alertness” was more marked and present in female caregivers 46,48,50. Both men and women expressed feelings of loneliness and sadness, and mentioned fear as a permanent state, in addition to the fear of suffering from the disease in a projection of their life in the future 46,47,50,53,54,57,61,68.

Male caregivers expressed negative feelings related to caregiving more frequently, such as anger, resentment, suicidal and homicidal ideation; however, it was more difficult for them to talk about their feelings, since their anxieties or fears were topics that they did not express to anyone, adopting the stance of men who can deal with anything 48,52-55,57,58,69.

Caregiving as an Act of Love

There is a close relationship between the informal caregiver and the sick person regarding care, which is provided with love, patience, and a sense of gratitude. Women expressed inclinations of indebtedness and gratitude towards the person cared for, generally because they were daughters and wives. In most cases, they were assigned the task of caregiving without the possibility of mediating the decision, but the role was accepted without a second thought due to ethical and family duty 46,48,55,56,68. However, women offer their care work based on love, willing to “always be on the lookout” and to try to respond to the demands of their loved ones, regardless of the state of health, the complexity of the diseases, or the physical and psychological compromises of the person receiving their care. The women expressed that it was the love between them and the person receiving care that gave them the strength to continue providing their care 45-51,55-59,61-64,66,68.

For the men, the process of accepting the caregiving role was progressive, as they gradually made commitments and adapted to the needs involved in caregiving. Initially, they reported that they did not want to take on this responsibility, but caregiving emerged as a mutual coping response, since while performing caregiving tasks, they strengthened the bond of family love. Still, they mentioned that they were recurrently focusing on the present and preparing for the future, an uncertain future for both themselves and their cared-for loved ones, where love would be the way to cope with any event 48,52-55,57,58,69.

Transcendence of Care: Between Spirituality and Religiosity

In terms of the relationship with God, men recognized that they had a relationship with a deity and that this presence was important as a form of spiritual support for the care they provided 48,52-55,57,58,69. Meanwhile, women also had a relationship with God, but this relationship was deeper spiritually, one of love, of spiritual reciprocity, which transcended the body and strengthened the spirit daily, having God as their source of strength and spiritual support 49,56,57,68.

Discussion

Care work is defined as helping people in a situation of dependency, concerning basic activities (such as eating or going to the bathroom) that ensure subsistence, and even activities that allow for maintaining social and participatory bonds 46.

History has shown that the caregiving role has generally been assumed by women as caregivers at different stages of their lives 51. In this sense, women’s choice to be caregivers is drastically influenced by their physical location (living with or very close to the person they are providing care for) and by the unwillingness of other family members to assume the role 64, being overwhelmed by the expectation of other family members who expect them to be the ones to provide such care 65.

Over time, there has been an increasing shift in responsibility towards male caregivers, who initially assumed secondary care to support female caregivers (daughters and wives) 49. This is due to the trend toward shorter hospital stays and the transfer of care to the home setting 52, which has meant that the burden of responsibility for male caregivers has impacted their daily lives over time, leading them to adopt the role of family caregivers as well 53.

Regarding the development of the caregiving experience, it is known that during this new stage, a considerable amount of time must be devoted to providing care to the dependent person, which is learned to generate proficiency as time passes. During this period, caregivers are afraid of making mistakes and harming their patients 61,65,66 and, in fact, it is evident that it is the fear of these situations that generates this sense of uneasiness, with feelings that negatively impact on their lives and on how they provide care 60.

For men, adopting this new role of informal caregiver commonly involves performing activities such as preparing and providing food, maintaining the hygiene of both the patient and the environment, and administering medications 48; on the other hand, for women caregivers the new role includes not only performing these same activities, but also others that strengthen their personal and social dimensions, such as encouraging the person receiving care to not lose hope, joining efforts to motivate them in their illness, and striving to show them that they (the caregivers) “will always be there” 48,49,51.

Being responsible for this role, appears suddenly and without warning 55, in addition to the large amount of time required for caregiving, which leads to life changes, limitations, and a perceived loss of control over the lives of caregivers of both genders. Caregivers describe feeling physically exhausted, losing control over the use of time to engage in leisure activities, as well as having little to no free time for themselves, and wishing to escape or run away to have some time for themselves alone 45-47,50,55,57,60,62,69.

As for men, full-time caregiving hinders them from carrying out other activities, leading to a decrease in their vitality and their interaction with the family and the community, as well as neglecting other roles and duties 57,62. Women caregivers, unlike men, do not exclusively exercise the caregiving role, but must also maintain the other roles they perform in their daily lives, and assume new ones, such as driving, buying clothes, and managing finances 45.

This role demands that caregivers reinvent themselves, adapt, and evolve through caregiving 65, which they do with love and reciprocity. It has been found that for both genders this caregiving role is a natural development of years of bonding and an instinctive act of love by personal choice to be “willing to be there for each other” 55. In the case of male caregivers, the act of caregiving is spontaneous, being mutual love what makes it possible for the caregiving spouses to adapt to the new responsibilities, even refusing to receive help from family and friends 53, while in other cases they report having difficulties in finding more social support after the diagnosis of their family member 52.

This strenuous unpaid work, which is performed daily on a fulltime basis, can end up leading to the onset of musculoskeletal problems, attributed to the assisted mobilization of the patient 50, and become a heavy burden that produces physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion because, despite all the effort, there is no recovery for their family member 55, which is disappointing to the extent that they neglect and sacrifice their lives. They also recognize that their life is far from the expected ideal, with feelings of sadness, a desire to die, hatred towards their relatives, internal confusion, and helplessness due to the stigma from friends, acquaintances, and neighbors regarding their family member’s illness and their care 62.

On the other hand, caregivers stated that love, concern, care, and the good things in life provide them hope, and a desire to keep the role and move forward 55; also, caregivers stated that affection for their families, solidarity, gratification, appreciation for their actions, commitment, and well-being were facilitating feelings 56.

Despite all the chaos stemming from caregiving, there is a bond that provides clarity, strength, and hope whenever caregivers and family members express that the connection with their faith and God positively impacts their lives and helps them cope with their family member’s illness, existence, and isolation 49. When the patient’s health condition worsens as a result of the disease and the stress from the threat of death escalates 54, caregivers who experience the progression of their family member’s health conditions, suffering, and lack of recovery are motivated to reach out to God to express their desire for their family member’s peaceful death and freedom from suffering 57.

Conclusions

The present study has provided insight into the meaning of the experience for men and women who dedicate their time to the care of people with CNCDs. Through the literature synthesis and findings, differences were found that define a complex and particular experience. Men focus their care on the comfort of the affected person, providing support in basic tasks of personal cleanliness, feeding, and household hygiene; however, they experience negative feelings regarding their role as caregivers, such as anger, resentment, and suicidal and homicidal ideas.

However, women’s role as caregivers remains prevalent, to the extent that they focus their efforts on constant care, providing spiritual, emotional, and physical support, and constructing a concept of care associated with “always being on the lookout”. Moreover, such care is not detached from the responsibilities they must assume simultaneously at home, in relation to food, children and, in some cases, household finances, for which they rely on God for support and strength to keep going and not give up.

Additional studies on caregivers focused on gender differences, are needed to contribute to the development of the caregiver role and to support the therapeutic plan by the nursing field for people with CNCDs. It is necessary to positively impact male and female caregivers to decrease the risk of overload, improve quality of life, and strengthen their role as key actors in the care of people with CNCDs.