Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Pensamiento & Gestión

Print version ISSN 1657-6276On-line version ISSN 2145-941X

Pensam. gest. no.30 Barranquilla June 2011

Corporate environmental orientation:

Conceptualization and the case of Andean exporters*

Orientación ambiental corporativa:

conceptualización y el caso de los exportadores andinos

Anne Marie Zwerg-Villegas

azwerg@eafit.edu.co

Economista de Virginia Tech University y Magister en Gerencia Internacional de Baylor University. Está vinculada al Departamento de Negocios Internacionales de la Universidad EAFIT desde 2007, donde coordina el Área de Internacionalización de la Empresa y postgrados en Negocios Internacionales.

Fecha de recepción: Junio de 2010

Fecha de aceptación: Abril de 2011

Resumen

Mientras más consumidores, empresas y gobiernos desarrollen conciencia de la degradación ambiental y tomen medidas para disminuir su contribución negativa, las prácticas verdes jugarán un papel más prominente en la gestión corporativa. Este artículo realiza una revisión de la literatura sobre modos de enverdecimiento, beneficios del mismo, métodos de implementación y mercadeo verde para proponer una conceptualización de enverdecimiento de la empresa dentro de los negocios internacionales, con una mirada especial al comportamiento dentro de países en vía de desarrollo. Una encuesta de trescientas diecisiete empresas pequeñas y medianas en Colombia, Ecuador y Venezuela determina las percepciones de las actividades verdes en las empresas andinas. Aunque los gerentes andinos tienen conciencia ambiental, no llevan a cabo niveles suficientes de medición, auditoría y reportaje. Igualmente, el concepto de gobernabilidad y empresas-pares puede limitar su responsabilidad.

Palabras clave: Mercadeo verde, responsabilidad ambiental corporativa, países andinos.

Abstract

As more consumers, firms, and governments become aware of environmental degradation and take measures to abate their negative contribution, green practices will play a more prominent role in corporate management. This paper conducts a literature review of firm greening modes, the proposed benefits of firm greening, implementation approaches, and green marketing in order to propose a framework for analyzing firm greening in the international arena, paying particular attention to behavior within developing countries. A survey administered to general managers of three hundred and seventeen small and medium sized Colombian, Ecuadorian, and Venezuelan firms determines the managerial perceptions of greening activities in Andean firms. Though Andean managers are environmentally aware, they do not conduct adequate levels of measurement, auditing, and reporting. Also, the concept of stakeholders and peer corporations may limit Andean firms responsiveness.

Keywords: Greening marketing, corporate environmental responsibility, Andean countries.

1. INTRODUCTION

As more consumers, firms, and governments become aware of environmental degradation and take measures to abate their negative contribution; green practices such as green marketing will play a more prominent role in corporate management. This paper begins with a literature review on the topics of firm greening motives, firm greening implementation, benefits of firm greening, and green marketing. Much has been written in the last decade on firm environmental motives and implementation. This literature review is presented in such a way as to conceptually categorize for firm analysis within international business studies, with particular attention toward firm behaviors within developing countries. This is particularly necessary given that Chamorro, Rubio, and Miranda (2009) have found that the vast majority of authors on these subjects were from Anglo-Saxon countries. In fact, 47.74% of their analyzed articles were authored exclusively by one or more researchers from the USA. Additionally, hypotheses about firm greening practices of Andean exporters are developed within this conceptualization.

The conceptual categorization is fully explained in the following sections. In the first section on why firms "go green", this review finds that there are two principal modes. The first mode is reactive and consists of compliance and normative motives. The second mode is proactive and consists of green performance and green cause motives. After discussing the motives for environmental firm responsibility, this paper takes a look at the potential benefits of firm greening and the approaches to implementation, ranging from control and prevention to product stewardship to environmental leadership. The final aspect of the literature review is that of green marketing.

Research on three hundred and seventeen exporters provides empirical evidence of green firm practices. This paper discusses particular issues regarding firm greening within the developing countries of Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

2.1. Why firms "go green"

Green business literature usually distinguishes between firms that are compliance-drivenn -those merely aiming to meet legal requirements- and firms that take a more proactive environmental stance-those basing environmental decisions on stakeholders other than just the government. The next two sub-sections will review the business literature regarding these two distinctions and offer a clear mental framework applicable in international business studies.

2.1.1. Reactive Mode

The reactive mode is one in which firms adopt environmental policies and practices in order to comply with environmental regulations and norms. The first component-coerced-reflects the changing environmental business practices over recent decades and across nations, beginning with the environmental crisis-coping mode predominant worldwide in the 1960s and 1970s and the compliance-reaction mode of developed countries in the 1980s (Berry and Rondinelli, 1998). In the second component-normative-firms green in order to comply with pressures other than domestic environmental regulation. As a generalization, firms that produce and commercialize commodities or other price-sensitive products tend to perform within the reactive mode since additional expenditures above and beyond compliance tend to be seen as detracting from the corporate bottom line.

2.1.1.1. Coerced

"Coerced" is the first component of the reactive mode, corresponding to what is referred to in the literature as "coerced", "compliance mode", or "compliance model" (Sharfman et al., 1997, 14; Forte & Lamont, 1998, 89; Miles & Covin, 2000, p. 306) and reflects the traditional business aim of stockholder wealth maximization. These firms, termed "crisis-oriented" in Petulla's (1987) model, "resistant" in Welford's (1995) scale, and "compliance-driven" in Buysse and Verbeke's (2003) study, will comply with regulated environmental practices in as much as the fines or penalties of incompliance are greater that the cost of implementation (cited in Pulver, 2007, p. 47). From the most traditional point of view, key corporate competencies may actually hinder leveraging environmental competencies (Rugman and Verbeke, 1998), and compliance costs may prove to be inhibitive and may become the incentive to avoid compliance (Lyon, 2003).

Of those models which identify various motives that cause firms to adopt environmentally friendly practices, most hold governmental regulation high (Henriques and Sadorsky, 1996, cited in Miles and Covin, 2000; Pulver, 2007; Fairchild, 2008). In particular, Rojsek (2001) found that managers of Slovenian manufacturing firms believe that the government holds primary responsibility for enforcing environmentally sound practices and argues that Slovenian-based firms have little incentive to act voluntarily in the interests of the environment. Similarly, Williamson et al. (2006) found no evidence that small and medium sized manufacturing firms in the UK would voluntarily go beyond minimum compliance.

As this paper intends to develop a framework for discussing the international aspects of firm greening, and particularly green marketing, the coerced component is here understood to be pressures to comply with national environmental regulation.

2.1.1.2. Normative

The second component of the reactive mode is termed "normative" and refers to corporate greening resulting from pressures by trade unions, professional associations, environmental nongovernmental organizations, local communities, shareholders, stakeholders such as suppliers, government agencies, and other strategic partners (Arora & Carson, 1996;

Sharfman et al., 1997, p. 14; Pulver, 2007, p. 46; Miles & Covin, 2000, p. 299). This work, again with a focus on an international business framework, includes foreign government regulation as a normative factor.

In principle, firms are not coerced to comply with foreign government environmental regulations; however, in an effort to reach and maintain international target markets, firms will react according to the governmental regulations of the target market in question, whether directly or indirectly by complying with client purchasing requirements which in turn comply with governmental requirements. Especially in the case of developing and emerging economies, the normative component will tend to be stronger than the coerced component given that national environmental regulations will tend to be nonexistent, unclear, lax, or inefficient. As these markets increasingly turn to international trading partners, foreign environmental standards will steadily become more important pressures toward firm greening. An ever-growing number of world governments have proposed the goal of sustainable development. "This may be little more than lip service, but as such platitudes become a reality, companies will be pressured to find more sustainable methods to produce goods and services" Sharfman (1997, p. 13).

Those firms functioning only within the reactive mode are more likely to have predilection for the "principle of public responsibility", arguing that firms are only responsible for those problems they directly cause or those problems which directly affect their interests. The question arises: how do firms identify their interests? Certainly firm interests correspond to firm stakeholders, but firms of all nations do not necessarily have the same concept of stakeholders.

2.1.2. Proactive Mode

Opposite to the reactive mode, the proactive mode is one in which firms adopt greening practices as a means of sustainable competitive advantage. Though contrary to other scholars, D'Souza et al. (2006) determine that consumers do not consider governmental regulation to be sufficient to protect the environment or that government is the principle entity responsible for environmental protection. Instead, consumers expect corporations to self-regulate. Based on the findings of this study, the "likely corporate strategy is that of organizational cultural reorientation toward the unconditional provision of environmentally safe products" (D'Souza et al., 2006, p. 154). The two components of the proactive modegreen performance and green cause-distinguish between the motivating factors driving firm greenness once environmental responsibility above and beyond regulation and norm is in effect. The generalization in this case would be the consumer goods corporation for which the proactive implementation of environmental practices could be source of marketplace differentiation.

2.1.2.1. Green Performance

The green performance component corresponds to what Berry and Rondinelli (1998) identify as the "proactive environmental management" that was occurring in developed countries in the 1990s as firms "anticipate the environmental impacts of their operations, take measures to reduce waste and pollution in advance of regulation, and find positive ways of taking advantage of business opportunities through total quality environmental management" (Berry & Rondinelli, 1998, p. 39). Miles and Covin (2000) agree that "the social, economic, and global environment of the 1990s has resulted in environmental performance becoming an increasingly important component of the company's value" (Miles & Covin, 2000, p. 299). Though the Berry and Rondinelli study and the Miles and Covin research are a decade old, much of their findings are still futuristic in the developing world.

The green performance component also reflects what international literature has termed the "voluntary approach", "preventive mode", "strategic model of environmental management", "the business case" and "the business performance motives" (Russo & Fouts, 1997; Miles & Covin, 2000; Williamson et al., 2006). Here, firms heed the calls for responsible corporate environmental behavior coming from investors, insurers, environmental interest groups, financial institutions, international trading partners, consumers, shareholders, suppliers, and communities and participate in what Weinberg (1998) identifies as "green marketing" or "caring capitalism" or what Petulla (1987) considers "cost-oriented" greening (cited in Pulver, 2007, p. 47). As the number of stakeholders concerned about the environment increases, firms find it operationally beneficial to take actions beyond regulations and norms.

Fairchild's (2008) game-theoretic approach demonstrates that incentives to make voluntary investments in environmental practices are based on "market-forces" and are a reaction to the increasing environmental awareness of consumers and investors. Prakash (2002) suggests that another important reason for this type of firm greening is to pre-empt future regulations and norms; rather than reacting to them subsequently, firms can participate in shaping future regulations.

As with the normative motive in the reactive mode, the firm's definition of "stakeholder" is again important, as it will affect which external forces the company observes and deems to be worthy of attending. As Buysse and Verbeke (2003) note, "the inclusion of environmental issues into corporate strategy beyond what is required by governmental regulation could be viewed as a means to improve a company's alignment with the growing environmental concerns and expectations of its stakeholders." They continue, "identifying salient stakeholders becomes a critical step... not all stakeholders are equally important for corporations when crafting environmental strategies" (Buysse & Verbeke, 2003, p. 453). Mirvis (1994) states that the principle of public responsibility, predominant in the reactive mode, is expanded to the "rule of relevance," which says that social responsibilities are to be relevant to the firm's interests. How do firms decide what and who is relevant? "There is profit to be gained from assuming an environmental leadership role among peer corporations" (Forte & Lamonte, 1999, p. 90). In an international business framework, the question arises as to which firms are considered to be peers-local only or international?

2.1.2.2. Green Cause

Whereas the green performance motive influences firm greening inasmuch as it provides marketplace and financial benefits, the green cause motive takes into consideration that firms have societal and environmental responsibilities that may or may not contribute to profitability. The green cause motive, the only firm greening motive that originates within the firm itself, may then be envisioned as "corporate rectitude", "enlightened capitalism", "extreme green", "the transcendent firm", or "transformational leadership" (Mirvis, 1994; Ginsberg and Bloom, 2004; Welford, 1995, cited in Pulver, 2007) whereby the environment is paramount in business decision-making and "allows no firm activity to upset ecological relationships" (Pulver, 2007, p. 47).

Green-cause motivated firms adopt green practices out of pure ethical conviction concerning environmental responsibility. Menon and Me-non (1997) lead the discussion of the green cause, coining the term "enviropreneurship" to refer to companies founded on ecological practices and policies and with the goal of creating revenue through exchanges mutually satisfying to the firm's financial and social objectives. The Mir-vis (1994) study of green cause front-runners suggested that whereas "traditionally theories of organizational change depict firms as responding to new circumstances in the marketplace and socio-political environment.. .[the green firms included in the research are] attempting to change the marketplace and the entire socio-political landscape..." (Mirvis, 1994, p. 93). Mirvis interprets this as an indication that the value-laden, ethical stance becomes an important "product" of that firm. He specifically questions, "Can corporations create values?" (Mirvis, 1994, p. 84).

Mirvis' (1994) interpretation is reflected in Pulver's (2007) "environmental contestation approach" in which "firms compete not only over products and prices but also over the conceptions of control that structure their organizational fields" (Pulver, 2007, p. 50). Such competition over "conceptions of control" can lead to significant restructuring of the longterm prospects for the interface between environment and capitalism. Kilbourne et al. (1997) refer to this as a "macromarketing challenge to the dominant social paradigm" as it is "self-defeating to teach consumers about green consumption when the underlying premise is that consumption itself can be allowed to continue to increase, albeit at a different rate or through different types of products" (cited in Amine, 2003, 378). Beyond just environmental practices, the green-cause motivated firm will strive for economic justice since "it could hardly be said that a company is ethical if its practices systematically worsens the situation of a given group in the society, while claiming to be green" (Oyewole, 2001, p. 249).

H1: The Andean company takes a reactive stance toward firm greening, doing so in order to comply with foreign target market regulation.

2.2. Benefits of firm greening

Though there is some evidence that firm greening and the related green marketing are becoming less attractive propositions as "accusations of 'greenwashing', poor performance, and price premiums have, on the surface, all conspired" against them (Amine, 2003, p. 376); the vast majority of international literature continues to suggest tangible and intangible benefits for the environmentally responsible firm.

In the 1990s, period in which firms of developed nations were principally functioning within the reactive mode, compliance and some degree of over-compliance were found to have operational, cost-based benefits to the firm in the form of material savings, increased production yields, less production downtime, better utilization of products, conversion of waste into useable materials, energy savings during production, lower storage and handling costs, safer workplace conditions, reduction or elimination of waste handling costs, product quality improvements, safer products, lower product costs, lower packaging costs, more efficient input usage, higher resale or scrap values, lower insurance premiums, and lower cost of capital (Porter & van der Linde, 1995; Miles & Covin, 2000; Prakash, 2002; Hart & Ahuja, 1996). On a more strategic, differentiation-based level, firm greening above and beyond mere compliance has been found to encourage process innovations, increase customer loyalty, improve workplace morale and motivation, and create first-mover advantages (Forte & Lamont, 1998; Johri & Sahasakmontri, 1998; Miles & Covin, 2000; Chen et al., 2006).

These results suggest that the traditional view of polarity of shareholder interests versus environmental interests is unfounded since these interests can be met simultaneously as the cost-based benefits and the differentiation-based benefits of firm greening create synergistic effects leading to an ethical corporate image, employee involvement and motivation, meeting of customer expectations, increased market share, and positive financial performance (D'Souza et al., 2006). So environmental management can become a source of sustainable competitive advantage while concurrently raising rivals' cost of entry given that the environmental practices of leading firms can lead to more stringent future norms and regulations (Miles & Covin, 2000; Prakash, 2002; D'Souza et al., 2006; Pulver, 2007).

The evidence of benefits accruing to the most tenacious green-performance and the green-cause motivated firm is less substantial, however there are indications. "Reputational advantage; as a function of credibility, reliability, responsibility, and trustworthiness; is enhanced by superior environmental performance" (Miles & Covin, 2000, p. 300). Superior environmental reputation, in turn, leads to advantages in pricing concessions, reduced investor risk, and increased strategic flexibility (Suh and Amine, 2002). Russo and Fouts (1997) found that firms with a reputation of superior environmental responsibility were rewarded in the marketplace with bottom-line gains. Succinctly said, "companies that are ethical also tend to be more profitable" (Oyewole, 2001, p. 240).

H2: The Andean company undergoing firm greening benefits of greater access to foreign target markets.

H3: The Andean company undergoing firm greening experiences higher costs of production.

2.3. Approaches to implementation

Fully implemented corporate greening would mean that the production process creates no waste, but rather, input for another process. Such industrial ecology would be the epitome of corporate environmental ethics and justice (Oyewole, 2001). This section classifies the various explanations of how and to what extent firms implement environmentally responsible practices.

Before analyzing particular efforts undertaken depending upon the firm's mode and motives, two, not necessarily mutually-exclusive, management theories explain why and when firms invest in environmental performance improvements: 1) the slack resource explanation suggests that a firm's positive financial returns provide for discretionary income that may be allocated to social or environmental projects that would not usually be considered within the budgetary capacity and 2) the good management theory indicates that efficient and innovative management teams will seek emerging sources of competitive advantage and that these sources may include aspects of social and environmental projects (Russo & Fouts, 1997; Graves & Waddock, 1997, cited in Miles & Covin, 2000).

2.3.1. Waste Minimization and Prevention

The waste minimization and prevention approach is a reactive strategy in the face of regulative or normative pressures. At the lowest level, limited resources are invested to comply with environmental legal requirements. Firms will often resist the passage and enforcement of regulation; and when firm action is required, this would generally be end-of-pipe mitigation rather than process innovation (Hart, 1995; Berry & Rondinelli, 1998; Buysse & Verbeke, 2003). As firms adj ust budgeting and managerial motivation toward a more responsible environmental stance, firms will begin to adapt and continually review their products and processes and use materials, processes, and practices to reduce, minimize, or eliminate pollution or waste at the source (Berry & Rondinelli, 1998). This implies that firms will begin to update and change organizational processes and policies.

2.3.2. Product Stewardship

As waste minimization and prevention becomes less compliance motivated and more ethically motivated and as firms emphasize source reduction and process innovation rather than end-of-pipe measures, the firm enters the product stewardship approach. While the first stages of this approach are arguably still preventative in nature, they are a step beyond the prevention aspects of the waste minimization and prevention approach since the firms begin to affect systemic changes across the organization (Buysse & Verbeke, 2003). The firm analyzes the environmental impacts associated with future product demand and competitive industry developments; adjusts production and product offer to the more specific needs of an educated consumer; designs products for disassembly, modular upgrasdeability, and recyclability; and adapts manufacturing processes to minimize the product's negative impact during its entire life cycle (Hart, 1995; Berry & Rondinelli, 1998).

2.3.3. Environmental Leadership

Environmental costs have traditionally been thought of as those which the firm assumes, affecting its bottom-line, or those externalities which affect society in general but for which the firm is not responsible. Though this line of thinking has been changing in developed countries for over a decade, developing countries have not yet participated in this discussion. The shift, however, occurs with the implementation of full-cost accounting. According to Hart, this is the first step toward sustainable development, requiring "long-term vision shared among all relevant stakeholders and strong moral leadership, which is a rare resource" (Hart, 1995). Specifically, firms take steps toward making environmental responsibility a company-wide obligation, promoting employee participation and decision-making, having an environmental champion in top management, discussing environmental issues and performance at board meetings, assessing and communicating environmental performance and deficiencies, and balancing environmental and profit-oriented priorities (Berry & Rondinelli, 1998).

While frequently the process of implementation of environmentally responsible practices is linear, just as we now see that some firms are "born global", some firms are "born green," as would be the case of the enviropreneurs previously discussed in the section of green cause. These companies "seem to be less constrained by traditional barriers to change, such as ignorance, parochialism, capital costs, and competing priorities" (Mirvis, 1994, p. 83).

2.3.3.1. Assessment Requirement

As firms transition toward an environmental leadership approach, they will analyze environmental performance; conduct benchmarking and research best practices; identify and quantify environmental liabilities; develop a plan to minimize past and future environmental liabilities; secure top management commitment and funding; set clear goals and measurable targets; and develop a formal monitoring, auditing, and reporting system (Berry & Rondinelli, 1998). Certainly, the quality of the outcomes of these steps will depend on the quality of the information gathered and analyzed. Some form of product life cycle analysis is necessary to accumulate significant data (Hart, 1995; Sharfman et al., 1997; Buysse & Verbeke, 2003). Only by having in place measurable performance indicators within a life-cycle oriented environmental management system can firms make verifiable claims about their level of environmental responsibility (Prakash, 2002).

H4: The Andean firm carries out waste minimization and prevention.

H5: The small and medium sized Andean firm does not carry out internationally recognized assessment and verification.

2.4. Green marketing

Though various terms exist-environmental marketing (Coddington, 1993), ecological marketing (Fisk, 1994; Henion & Kinnear, 1976), green marketing (Peattie, 1995), sustainable marketing (Fuller, 1999), and greener marketing (Charter & Polonsky, 1999); this paper will utilize the term green marketing, which will be understood as the treatment of the natural environment within the marketing mix as well as the communication of the respect for the natural environment within the firm itself.

Shi and Kane (1996) define as green marketing plan success factors: 1) product-including the six R's of repair, recondition, remanufacture, reuse, recycle, and reduce, 2) packaging-recycled, recyclable, reduced, or reusable, 3) practice-such as those discussed in the section on implementation, and 4) promotion-advertising, public relations, direct sales, or personal sales that lets be known one of the previous criteria. The criterion of green packaging tends to be the first and most often implemented, and green promotion tends to be the most delicate since improper use can result in negative consequences in the marketplace (Bonini et al., 2007).

As firms progress through the modes of firm greening and the approaches to implementation, they will often see fit and profitable to communicate this progress in the marketplace. As part of the genre of responsible marketing, green promotion is expected to be honest; the contrary is termed "greenwashing". Firms can "avoid accusations of greenwash by being genuinely green and not by using ethics as just another piece of kit in the marketing toolbox" (Thomas, 2008, p. 23).

Given that consumers are expecting greater corporate environmental responsibility and that green promotion is an effort to convince the consumer of this responsibility, it is important to understand the factors that contribute to the consumers' perception of green marketing. D'Souza et al. (2006) identify six factors: 1) perception of the company as a whole, 2) compliance with environmental regulation, 3) perception of the relationship between price and quality, 4) perception of the product characteristics, 5) product labeling, and 6) previous experience with the company or product. Despite firm efforts to adopt genuine green marketing strategies, many customers continue to consider non-green attributes more important in their purchasing decisions (Johri and Sahasakmontri, 1998).

H6: The Andean company that employs a green marketing strategy concentrates on green product and packaging.

H7: The Andean company that employs a green marketing strategy commands higher prices in the marketplace than the equivalent Andean company that does not employ a green marketing strategy.

3. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY

The current research has the objectives of analyzing the Andean firm modes of greening, benefits of firm greening, approaches to implementation, and green marketing practices as each was defined in the conceptual categorization of the preceding literature review.

Specifically, this research tests the following hypothesis:

H1: The Andean company takes a reactive stance toward firm greening, doing so in order to comply with foreign target market regulation.

H2: The Andean company undergoing firm greening benefits from greater access to foreign target markets.

H3: The Andean company undergoing firm greening experiences higher costs of production. H4: The Andean firm carries out waste minimization and prevention. H5: The small and medium sized Andean firm does not carry out internationally recognized assessment and verification. H6: The Andean company that employs a green marketing strategy concentrates on green product and packaging. H7: The Andean company that employs a green marketing strategy commands higher prices in the marketplace than the equivalent Andean company that does not employ a green marketing strategy.

Managers of one hundred and eighty-five Colombian companies, across sectors, responded to an on-line survey, administered between April and August of 2008, about greening practices and motives. Responding firms were headquartered in the cities of Barranquilla, Bogotá, Bucaramanga, Cartagena, Ibagué, Medellín, and Pereira-seven of the ten largest and most industrialized cities of Colombia. With some ninety-eight percent of Colombian companies being small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs), an equal percentage of SMEs participated in the survey. As defined by the National Association of Foreign Trade (ANALDEX), SMEs are considered to be those with assets between $231 000 000 and $2 308 000 000 Colombian Pesos and number of employees between 11 and 200. The firms had a minimum of three years exporting experience and a minimum of 15% of total sales revenue generated from exports. Qualitative details were obtained through telephone and face-to-face interviews with random respondents.

Managers of one hundred and thirty-two Ecuadorian and Venezuelan firms, across sectors, responded to the same on-line survey, between February and May of2009. Again, the overwhelming majority of responding firms were SMEs. No telephone or face-to-face interviews were conducted with the Ecuadorian and Venezuelan managers.

Conclusions particular to the Colombian firms can be found in Zwerg Villegas (2008); but for this work, given the homogeneity of responses from Colombian, Ecuadorian, and Venezuelan firms, the results will be stated as an Andean conglomerate.

4. RESULTS

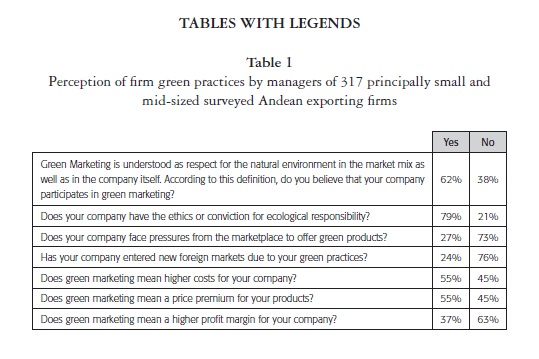

Results are detailed in tables 1 and 2 and are further discussed in the following section.

H1, which states that the Andean company takes a reactive stance toward firm greening, is partially supported depending on the firm sector.

Seventy-nine percent of respondents perceive that their companies hold environmental ethics or conviction, but a lesser percentage (sixty-two percent) view themselves as meeting the definition of green marketing.

H2, which states that the Andean company undergoing firm greening benefits from greater access to foreign target markets, is not supported by the perceptions of the responding managers.

Contrary to research expectations, only twenty-seven percent of respondents perceive marketplace pressures to offer green products, and only twenty-four percent have entered new foreign markets due to green marketing practices.

An equal number (fifty-five percent) perceive both higher costs to the company and price premiums due to green marketing practices.

So H3, which states that the Andean company undergoing firm greening experiences higher costs of production, is supported by the perceptions of responding managers.

Perception of higher costs is equally distributed amongst the alternatives of green product, green packaging, green corporate practice, and green promotion.

The largest number of respondents, forty percent, perceives that green products command a price premium.

The most frequently applied green marketing strategy, with thirtysix percent of respondents, was in green corporate practice. Forty-four percent (the largest response) of firms perceive that implementation of green corporate practices is the best green alternative to attract new consumers in an export market.

H4, which states that the Andean firm carries out waste minimization and prevention, is partially supported by perceptions of responding managers.

H5, which states that the small and medium sized Andean firm does not carry out internationally recognized assessment and verification, is not accurately tested and supported in this study but will be discussed in the following section.

Again, contrary to research expectations, only thirteen percent of respondents utilize green packaging, though twenty-nine percent perceive that this would be an alternative to increase international sales.

H6, which states that the Andean company that employs a green marketing strategy concentrates on green product and packaging, is not supported by perceptions of responding managers.

5. DISCUSSION

These survey results contradict international data, as previously discussed in the sections detailing the theoretical framework, in three important ways: 1) the Andean firm implements green packaging at a lower rate than the other green marketing alternatives whereas international data show that this is usually the first and most frequent green marketing strategy, 2) the Andean firm perceives a price premium for green products whereas international data show that consumers are largely unwilling to pay a price premium for green products, 3) the Andean firm only vaguely feels pressures to provide green products whereas international data indicate that consumers are eager to buy green products. Through interviews with the respondent firm executives, these latter two contradictions can be explained by the fact that these firms have only limited export activity to the countries where a grand portion of the market is demanding environmentally conscious products. In turn, these firms have greater activity with neighboring, developing countries where the concept of green marketing is not yet strong but within those countries have niche markets willing to pay a price premium for green products.

Interviews determine additional contradictions. One is that firms that produce and commercialize commodities and price sensitive products are more likely to enter into a proactive mode than act in the reactive mode. It would be expected that such firms would remain reactive and only minimally compliant in order to limit costs. In the Andean case, however, with limited internal demand, firms are required to participate in international markets. While the previously offered framework indicates that international environmental compliance is a normative motive within the reactive mode, these firms feel that they are being proactive because they still view international commerce is a proactive choice rather than a business requirement. Also, being truly proactive within the framework, they face such intense price competition from lower-cost producers that they have initiated proactive greening in order to differentiate themselves.

On the same note, and equally contradictory, is that firms that produce and commercialize consumer products are more likely to perform within the reactive mode. The supposition is that the differentiation required for consumer goods will move firms into a proactive mode. In the Andean case, the consumer goods industry has a significant internal market compared with its international market. This internal market is highly homogeneous in terms of demand and supply. Therefore, given the intense competition, firms resist proactive greening in order to maintain minimal environmental costs and, hence, minimally comply with local environmental regulation.

As was to be expected, the normative motive plays a greater role overall than does the compliance motive. National environmental regulation is non-existent, inadequate, corrupt, and lax. If there were to be any fines or penalties for noncompliance, the values would be less than the cost of implementing environmentally responsible practices. There are many very obvious examples of major firms that do not comply and evidently do not face any major deterrents. Just a drive down the principal highway, one will easily see the waste water of even government-owned firms being channeled into major waterways. A simple explanation is that the politicians are usually business owners as well and that executives are often on the board of directors of one another's firms. As primitively rational actors, they resist passage and enforcement of environmental standards, keeping their own firms' costs down while increasing the costs to society. The society, largely uneducated in environmental matters, does little or nothing to call for more.

Andean society, much like in other developing and emerging economies, enjoys conspicuous consumption. Large, gas-guzzling SUVs are the automobile of choice as are lavish homes and flashy lifestyles. Any environmental call for reducing consumption rings too similar to the poverty the people are pleased to be escaping.

At the same time, this move away from poverty in recent years is a main reason that any firm greening occurs. As the slack resource explanation suggests, firms' recent positive financial performance provides funds for implementation of environmentally responsible practices. Many firms combine the slack resources explanation and the good management explanation in order to simultaneously invest in environmentally sound processes and procedures and thereby reap advantage of emerging sources of competitive advantage. In particular, apparently "born-green" firms have emerged in recent years. However, discussion with management reveals that these enviropreneurs are "environmental leaders" only as long as this strategy reins profit. Should economic conditions turn for the worse, these entrepreneurs will switch the course of business in any way necessary to maintain financial status quo.

Another phenomenon discovered amongst many self-perceived green firms is that while the product and practices of the firm itself may very well be environmentally responsible, the complete value chain surrounding that firm is far from it. A specific example is that of manufacturers of raffia bags and accessories. These firms perceive themselves to be green given that their products are substitutes for plastics and are manually intensive. However, a simple study of the raffia value chain proves that the crops are most often grown with heavy pesticide use and that some ninety percent of the plant is wasted. That waste is dumped directly into waterways.

Another specific example demonstrates that many self-perceived green firms are misinformed about what it takes to be genuinely green: a beef manufacturer exporting "organic beef was caught off-guard when trade relations were abruptly halted with major international buyers when those buyers found that the manufacturer's definition of "organic" was not the accepted definition.

These two examples point to two important topics in the discussion of firm greening: 1) measurement systems and 2) salient stakeholders. As was discussed in the section on assessment requirement, an essential step in firm greening is that of analyzing environmental performance, identifying liabilities, setting clear and measurable goals, and monitoring performance toward those goals. This step is largely unheard of in Andean firms. Most Andean firms are ignorant of or uninterested in conducting such monitoring and auditing. Costs required to implement this step are also prohibitive. If the firm cannot measure its environmental performance, does it have any factual basis on which to pronounce its greenness? On a positive note, nonetheless, firms do realize this limitation and refrain from making unverifiable claims in promotion. Therefore, greenwashing is not concluded to be common from Andean firms.

The other topic, salient stakeholders, has been a recurrent topic throughout this paper. In the Andean case, little consideration for stakeholders other than shareholders is given. This is a cliché "us" versus "them" situation. Management, politicians, and shareholders are the "us" while the communities polluted with firm emissions are "them". The wealthy "us" group lives in luxury communities withdrawn from industrial contamination and even has the facilities to move further-United States or Europe for example-if conditions get bad enough. International firms are also considered to be "them". As relatively recent participants in international trade, Andean firms do not perceive the need to benchmark internationally. Executives, shareholders, board members, and politician sintermingled amongst themselves-benchmark one against the other and, as would be expected, find that they are quite comparable. Each individual firm, therefore, feels vindicated that what that firm is doing must be the norm or even the state-of-the-art.

In conclusion, Andean exporters are aware of trends in firm greening. Many express interest and conviction in the topic. However, with little perceived demand for greener products, firms feel limited incentive to offer green products, green packaging, or green promotion. There are efforts toward implementing environmentally responsible practices at the corporate level. Nevertheless, firms do not extend their perception of environmental responsibility toward environmental justice. Relevant stakeholders and peers tend to be executives and firms similar to themselves. By only conducting benchmarking with others who are essentially like them, there is little capacity to acquire additional knowledge about environmental issues and environmentally responsible practices.

* Research financed by the Direction of Research and Teaching, Universidad eafit.

References

Chamorro, A., Rubio, S. & Miranda, F. (2009). Characteristics of Research on Green Marketing. Business Strategy and the Environment, 18, 223-239. [ Links ]

Berry, M.A & Rondinelli, D.A. (1998). Proactive corporate environmental management: A new industrial revolution. The Academy of Management Executive, 12 (2), 38-50. [ Links ]

Sharfman, M., Ellington, R. & Meo, M. (1997). The Next Step in Becoming 'Green': Life-Cycle Oriented Environmental Management. Business Horizons, 40 (3), 13-22. [ Links ]

Forte, M. & Lamont, B. (1998). The bottom-line effect of greening (implications of ecological awareness). The Academy of Management Executive, 12 (1), 89-91. [ Links ]

Miles, M. & Covin, J. (2000). Environmental Marketing: A Source of Reputational, Competitive, and Financial Advantage. Journal of Business Ethics, 23 (3), 299-311. [ Links ]

Buysse, K. & Verbeke, A. (2003). Proactive environmental strategies: A stakeholder management perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 24 (5), 45370. [ Links ]

Pulver, S. (2007). Making sense of corporate environmentalism. Organization & Environment, 20 (1), 44-83. [ Links ]

Rugman, A. S Verbeke, A. (1998). Corporate strategies and environmental regulations: an organizing framework . Strategic Management Journal, 19 (4), 363-75. [ Links ]

Lyon, T. (2003). Green firms bearing gifts. Regulation Washington, 26 (3), 36. [ Links ]

Fairchild, R. (2008). The Manufacturing Sector's Environmental Motives: A Game-theoretic Analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 29, 333-44. [ Links ]

Rojsek, I. (2001). From red to green: Towards the environmental management in the country in transition. Journal of Business Ethics, 33 (1), 37-50. [ Links ]

Williamson, D., Lynch-Wood, G. S Ramsay, J. (2006). Drivers of Environmental Behaviour in Manufacturing SMEs and the Implications for CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 67, 317-30. [ Links ]

Arora, S. & Cason, T. (1996). Why do firms volunteer to exceed environmental regulations? Understanding participation in EPA's 33/50 program. Land Economics, 72 (4), and 413-32. [ Links ]

D'Souza, C., Taghia, M. Lamb, P. S Peretiatkos, R. (2006). Green products and corporate strategy: an empirical investigation. Emerald Society and Business Review, 1 (2), 144-57. [ Links ]

Russo, M. S Fouts, P. (1997). "A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental performance and profitability". Academy of Management Journal, 40 (3), 534-59. [ Links ]

Prakash, A. (2002). Green Marketing, Public Policy and Managerial Strategies. Business Strategy and the Environment, 11 (5), 285-97. [ Links ]

Mirvis, P. (1994). Environmentalism in Progressive Business. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 7 (4), 82-100. [ Links ]

Ginsberg, J. M. & Bloom, P. (2004). Choosing the Right Green Marketing Strategy. MIT Sloan Management Review, 46 (1), 77-84. [ Links ]

Menon, A. & Menon, A. (1997). Enviropreneurial marketing strategy: the emergence of corporate environmentalism as a market strategy. Journal of Marketing, 61(2), 51-67. [ Links ]

Amine, L. (2003). An integrated micro- and macrolevel discussion of global green issues: It isn't easy being green. Journal of International Management, 9, 373-93. [ Links ]

Oyewole, P. (2001). Social Costs of Environmental Justice Associated with the Practice of Green Marketing. Journal of Business Ethics, 29 (3), 239-51. [ Links ]

Porter, M. & van der Linde, C. (1995). Toward a new conception of the environment/competitiveness relationship. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9 (4), 97118. [ Links ]

Hart, S. & Ahuja, G. (1996). Does it pay to be green? Business Strategy and the Environment, 5, 31. [ Links ]

Johri, L. & Sahasakmontri, K. (1998). Green marketing of cosmetics and toiletries in Thailand. The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 15 (3), 265-66. [ Links ]

Chen, Y., Lai, S. & Wen, C. (2006). The Influence of Green Innovation Performance on Corporate Advantage in Taiwan. Journal of Business Ethics, 67, 33139. [ Links ]

Suh, T. & Amine, L. (2002). Defining and managing corporate reputational capital in global markets: Conceptual issues, analytical frameworks, and managerial implications. American Marketing Association Conference Proceedings, AMA Winter Educators' Conference 13, 5-6. Chicago. [ Links ]

Hart, S. (1995). Natural-resource-based view of the firm. Academy of Management Review, 20 (4), 986-1014. [ Links ]

Coddington, W. (1993). Environmental Marketing: Positive Strategies for Reaching the Green Consumer. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Fisk, G. (1974). Marketing and the Ecological Crisis. London: Harper and Row. [ Links ]

Henion, K. & Kinnear, T. (1976). Ecological Marketing, American Marketing. Chicago: Association. [ Links ]

Peattie, K. (1995). Environmental Marketing Management. London: Pitman. [ Links ]

Fuller, D. (1999). Marketing mix design-for-environment: A systems approach. Journal of Business Administration and Policy Analysis, 27, 309. [ Links ]

Charter, M. & Polonsky, M.J. (1999). Greener Marketing: A Global Perspective On Greening Marketing Practice, Greenleaf Publishing Sheffield. [ Links ]

Shi, J. S. & Kane, J. (1996). Green Issues. Business Horizons, 39 (1), 65-70. [ Links ]

Bonini, S., McKillop, K. & Mendonca, L. (2007). The trust gap between consumers and corporations. The McKinsey Quarterly, 2, 7-10. [ Links ]

Thomas, J. (2008). Go green, be ethical, and stay genuine. Marketing, 23. [ Links ]

Zwerg-Villegas, A. (2008). Incidences and Analysis of Green Marketing Strategy in Colombian Exports. Ad-Minister, 13 (2), 9-19. www.analdex.org [ Links ]

Tables with legends