1. INTRODUCTION

The armed conflict in Colombia is the result of the absence of dispute resolution without the use of violence in all its denominations as an instrument of coercion of all sides of the conflict. For Garcia (2015) the peace process does not mean the end of the military confrontation between the army, the guerrilla and criminal groups. Maldonado et al (2018) and Morales (2018) mention that the peace agreement requires creating welfare programs that suppose a fiscal pressure for future governments. However, Colombia has imposed an upper-limit of its fiscal deficit based on the implementation of Law 1473 of 2011 in which the government must maintain a downward path for the structural fiscal deficit so for 2014 it could be equal or less than 2.3 % of GDP; in 2018, maximum 1.9% of GDP, and in 2022, 1% of GDP. This dynamic would lead to public debt spend 38% of GDP in 2010 to 34 % in 2014 and 30 % in 2020 (Ojeda-Joya et al, 2016; Thorton et al, 2017; SANABRIA-LANDAZÁBAL et al., 2017; de la Puente Pacheco, 2017a; de la Puente et al., 2018; Portafolio, 2014).

This research analyzes the budget pressure involved in the implementation of the peace agreement between the government of Colombia and the FARC-EP based on the institutional approach from Parada (2016) who mentions that institutional strength and tax equity facilitate the achievement of medium and long-term social and economic projects. It is found that a high tax burden on companies, the tax evasion from individual taxpayers and legislative constrains makes difficult the acquisition of monetary resources for an effective implementation of the peace agreement (De la Puente Pacheco, 2017b).

The general objective is to study the budgetary pressure that implies the implementation of the peace agreement. The specific objectives are to describe the projections of saving and spending derived from the peace agreement, establishing a qualitative correlation between the current high public debt, fiscal law restrictions and the need to acquire financial resources for a full implementation of the post-agreement. The working hypothesis is based on the idea that the peace agreement financing goes through a greater individual tax contribution compared to public and private companies based on acquiring more financial assets from tax evasion.

This research contributes to a current debate regarding the source of future monetary resources for the full implementation of the peace agreement.

2. FLEXIBLE INSTITUTIONS: A NON-TRADITIONAL PERSPECTIVE

Parada (2016) mentions that the budgetary dynamics pursue major objectives that include the guarantee of social welfare, the operations of public entities over time and in contexts of organizational changes, the implementation of orthodox economic perspectives remains short in understanding dynamic realities. Therefore, the author argues that decision making derived from simplistic approaches to changing realities can generate imbalances in the burden of social, economic and political agents. For the author, Colombia needs a new fiscal approach to ensure a public budget for post- agreement following a heterodox perspective where the budget balance is not the only purpose of the Colombian fiscal policy.

Funding for post- agreement process allows the implementation of strategies to facilitate peaceful change in multiple ways based on public spending increasing. The main axes of post-agreement are building citizenship, strengthening of national and local institutions, and implement public programs for equity and the inclusion of armed actors to civilian life.

However, Cardenas (2015), Byrne et al (2011) and Rincon et al (2017) underline that with a macroeconomic structure in deep imbalances resulting from the concentration of exports in non-traditional goods and fluctuations in the external sector, the funding of the post- agreement process is a major challenge where university-industry cooperation will be vital for the study and implementation of competitive strategies to achieve social equity. Post- agreement funding can accelerate or delay the implementation process of the peace agreement where there are humanitarian activities such as the support for displaced populations, the demobilization and reintegration of insurgents into civilian life, the private sector participation, the reactivation of inclusive agribusiness sector and the formalization of economic activity through reducing unemployment and underemployment are the basis to prevent future armed conflicts coming from socio-political causes (Roca, Giraldo, Bautista, 2011) (Sanchez-Zamora et al, 2017) (Maldonado et al, 2018).

With these budgetary pressures, Dupuy (2009) proposes that costs be distributed equally among all actors of the armed conflict (direct and indirect). The author highlights the experiences of the increase in the fiscal burdens of peace accompanied by national educational policy on the benefits of order, has facilitated multiparty support of spending in various social sectors. This coincides with the educational results found by De la Puente et al. (2019) which show the correlation between meaningful learning in conflict contexts through unconventional methods of teaching and the willingness to assume more significant commitments to the problem.

3. SAVINGS PROSPECTS AND POST-AGREEMENT SPENDING

According to Parada (2016) post-agreement represents a substantial increase in domestic production and reduction in environmental costs. It is expected an additional production of 110,000 hectares of additional land which would result in 700,000 additional tons of food (Arias, Ibanez, 2012), a US$ 7.1 billion in savings as a result of forest-area recoveries (DNP, 2015). The expenditures are estimated in around $25-$40 billion Colombian pesos for the implementation of Law 1448 of 2011 concerning welfare measures, assistance and comprehensive reparation to the victims of armed conflict, which according to the National Center of Historical Memory (2016) in the period 1996-2012 reached 4'744,046.

The injection of resources for the implementation of transitional justice for ex-combatants is a very significant budgetary pressure. At the end of 2015, US$670 million for the demobilization and reintegration of out-law armed groups had been spent (Olave, 2016; de la Puente Pacheco, 2015a). The Colombian Agency for Reintegration (ACR, 2015) estimates that the demobilization of all members of the FARC-EP who wish to return into civilian life costs approximately US$164 billion within 5 years representing a total cost of rehabilitation around $2,7 billion Colombian pesos (Department of Fiscal Control of the Republic, 2013) (Brazeal, 2016).

This represents a substantial decrease in resources allocated to the armed conflict from the military perspective in a context where warlike actions, attacks on civilian properties have consistently pressed the whole country. The peace talks have resulted in a decrease of the warlike actions of the FARC-EP, ELN and other guerrillas increasing the general budget of other areas such as education.

4. RESOURCES FOR POST-AGREEMENT FROM THE PUBLIC DEBT

Article 5 of the law of fiscal rule underlines that the government spending should not overstep the total income of the country exceeding the annual target of the structural fiscal balance. Article 6 of the same law mentions that the national government can implement countercyclical spending in a year with no more than two percentage points below the rate of real economic growth in the fiscal year in which the measure is applied. According to Bank of America, $187 billion Colombian pesos are required to fund the post- agreement for the next ten years. The transitory Commission of Peace of Congress sets COP$23,2 - COP$23,7 billion in a four-year period, the Senate of the Republic determines about COP$10 billion to 10 years, and Merryl Lynch Global Research estimates COP$30 billion to ten years as well. Sarmiento (2015) and Plazas Vega (2015) mention that the suspension of the fiscal rule by the Superior Council of Fiscal Policy (CONFIS) can be made by Article 14 of Law 1473 of 2011 based on: 1) the definition of basic parameters required for the operation of the fiscal rule; 2) analysis of the proposals made by the Government about methodology changes for defining the fiscal rule; 3) a Compliance report of the fiscal rule that the Government must submit to the Economic Commission of the Congress of the Republic, 4) Suspension of the fiscal rule.

In the global scenario, Dupuy (2009) mentions that the flexibility of public and private debt ceilings can be revised under conditions tied to the resolution of conflicts. Among these, allowing private companies greater indebtedness under the condition that they hire former actors of the conflict.

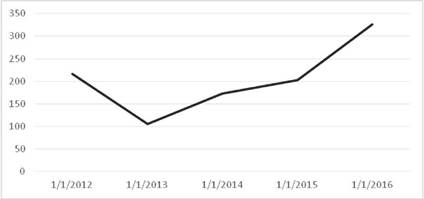

It should be noted that between 2014 and 2015 the public sector debt grew in more than US$10.000 million (Bank of the Republic, 2016) which could affect the country risk and future conditions of indebtedness. If it is considered that the interest rate of the national debt and the confidence of international markets tin Colombia is based (among other components) on the indicator of Country Risk (exposes how much should a fixed security pay from the difference between the yield of a domestic bond minus the yield of a United States bond for the same period of time called in basic points, the higher the score the lower the interests) would expect the interest rate to be paid for obtaining foreign loans (Ministry of Finance, 2016; De la Puente Pacheco, 2018).

Source: Personal compilation based on data found in Ambito.com. (2016). Country Risk: Colombia. Retrieved from http://www.ambito.com/economia/mercados/riesgopais/info/?id=4&desde=02/01/2012&hasta=29/06/2016&pag=5.

Chart 1 Evolution of Country Risk of Colombia: 2012-2016.

The possibility of financing part of post- agreement with more national debt is not hare-brained (Sarmiento, 2015; Grobéty, 2018; Tran, 2018). It is expected that the only area that would be affected would be the armed forces, releasing about COP$16 billion annually in a progressive way, which would not be sufficient to finance the post- agreement while Health and Education areas cannot be reduced according to sentence C -931 of 2004 of the Colombian Court of Justice (Butowski, 2018).

5. RESOURCES FOR POST- AGREEMENT FROM TAXATION

According to Piza et al (2015) and De la Puente Pacheco, (2015b) the national government has introduced various tax reforms seeking sufficiency in the collection, horizontal equity, vertical escalation, economic and administrative efficiency as a result of external shocks resulting from fluctuations in oil prices, strengthening dollar, negative perspectives about foreign trade with strategic partners, and internal shocks such as high inflation, high underemployment, among others. However, the tax collection in Colombia is below the average for countries belonging to the OECD and Latin America (De la Puente, 2012) (Presbitero et al, 2014) (Radu, et al, 2018) which calls for a review of the current tax burden and a rethinking to improve the efficiency of the system. Authors such as Scott (2007), Mitra (2017) and Epstein et al (2016) call for the reduction of tax evasion (mainly of individual taxpayers) which can help important public spending projects such as the implementation of the Colombian peace agreement (Pacheco, 2018; Pacheco, 2019).

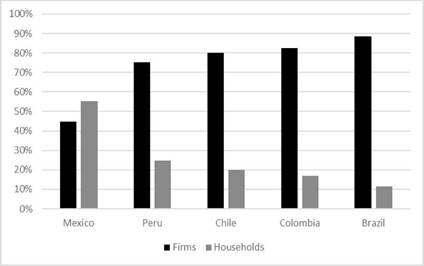

Source: Personal compilation based on data found in Insignares, RA., Piza, J., Sarmiento, J. (Ed.). (2015). Comisión para el estudio Del sistema tributario en Reforma Tributaria. Ley 1739 de 2014. Reflexiones Académicas y Empresariales. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia.

Chart 2 The income tax rate on companies (including CREE) for Latin America, OECD and Colombia: 2007-2017 (estimated).

Source: Personal compilation based on data found in Ambito.com. "Risk Country: Colombia." (May, 2016) // http://www.ambito.com/economia/mercados/riesgopais/info/?id=4&desde=02/01/2012&hasta=29/06/2016&pag=5

Chart 3 Total tax revenue in Latin America, OECD and Colombia as a percentage of GDP: 2004-2014.

The collection levels in the country are low due to problems such as evasion, logistics difficulty in monitoring, and the establishment of deductions with transitory nature which become permanent. However, and faced with a funding scenario of post- agreement, the country has higher levels of taxation for enterprises, as well as a high average of indirect taxes which reduces the room for future tax increases after 2016.

For De la Puente (2012) the higher taxation to national or foreign firms in Colombia supposes a greater pressure than what they have now; according to Plazas Vega (2015), national and local taxes can reach 68% of total revenue of medium size companies. It is expected that through the reduction of tax evasion, resources for post- agreement could increase by the end of 2018. The tax evasion in Colombia is around COP$28 Billion only referred to income tax and VAT. It is expected that tax evasion can be reduced in two ways. The first one is to strengthen the internal revenue service department by acquiring more human capital and technological instruments to reduce tax evasion in a more efficient way (Richardson, 2006) (Kafkalas et al, 2014) (Semana Magazine, 2015).

The second is the formalization of economic activities which are allowed to control evaders from cross-checking information from various State organizations.

Source: Personal compilation based on data found in Insignares, RA., Piza, J., Sarmiento, J. (Ed.). (2015). Comisión para el estudio Del sistema tributario en Reforma Tributaria. Ley 1739 de 2014. Reflexiones Académicas y Empresariales. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia.

Chart 4 Contribution of companies and individuals to the collection of direct taxes for 2014.

6. CLOSING REMARKS

In the current post- agreement process, the acquisition of monetary resources for the full implementation of the peace agreement is mainly based on political will and increase in the current revenues sources from direct and indirect taxes.

This would need a partial suspension of the fiscal rule adopted in 2012 in Article 14 which would generate financial risks both internally and externally and future lowering in the national credit rating of the major international rating agencies.

This in turn could cause an increase in the cost paid by the country for future long-term sovereign debt and increase in investor's risk perception. It is necessary to establish an appropriate tax policy to face the full implementation of the peace agreement.

In the absence of specific numbers that the full implementation would cost and giving the current tax evasion in the country, several authors' mentioned above promote an increase in direct and indirect taxes for individual taxpayers. Even though unpopular, it is necessary to do what was agreed upon in the peace process and ensure an equitable distribution of income in areas that benefit from the agreement in the short term.

At times when the full compliance of the peace agreement and the international commitments assumed by Colombia are debated, it should not be forgotten that the agreement is not only a document that links fiscal resources to mitigate the country's backwardness in many aspects, but also to lay the bases to promote sustainable economic development.