Introduction

As peer relationships assume greater importance during adolescence, these relationships become more complex. Adolescents begin to face new social dilemmas and must learn to navigate varying relationship dynamics, including conflict with peers (Brown & Larson, 2009). In early childhood, these conflicts often take the form of arguments or struggles over objects (Chung & Asher, 1996). As children mature into adolescents, conflicts with peers are most often over relationship problems and over differences of ideas or opinions (Laursen, 1995). Additional sources of peer conflict during adolescence are exclusion from social groups, intrusive behavior such as stealing and intimidation, and jealously over another person’s possessions (Sidorowicz & Hair, 2009). The purpose of this study was to identify the goals and strategies that adolescents use to solve peer conflict and examine their association with aggressive behavior. Identifying modifiable factors associated with aggression can help researchers and educators develop meaningful programs to reduce aggressive behaviors and develop a positive school climate.

Peer conflict, defined as mutual disagreement or hostility between peers or peer groups, has long been associated with the period of adolescence and may play an important developmental role (Collins & Laursen, 1992; Noakes & Rinaldi, 2006). Many developmental researchers believe that conflict with peers can lead to positive contributions to adolescents’ social, psychological, and cognitive development (Deutsch, 1973; Shantz, 1987; Shantz & Hobart, 1989). Effective management of peer conflict may reduce egocentrism, promote social understanding, and enhance discourse skills among youth (Chung & Asher, 1996).

However, conflict with peers can sometimes be violent and destructive (Selman, 1981; Shantz & Hobart, 1989). For this reason, conflict is commonly viewed as a negative and undesirable event that can lead to significant emotional and physical harm (Hocker & Wilmot, 1991; Sidorowicz & Hair, 2009; Sun & Hui, 2007). Researchers interested in the role of peer conflict in children and adolescent development have primarily focused on aggression as a behavioral outcome of conflict. Several researchers have found that children with high levels of aggression and difficulty with conflict management are more likely to be rejected by their peers and tend to adjust poorly to friendships (Coie, Dodge, & Kupersmidt, 1990; Rose & Asher, 1999). As a result, this difficulty with friends may lead to detrimental outcomes later in life such as low self-esteem, poor school achievement, school dropout, and delinquency (Berndt & Keefe, 1992; Opotow, 1991). In contrast, children who are prosocial and can resolve peer conflict effectively are more likely to be well accepted by their peers and their friendships tend to become more meaningful (Coie et al., 1990; Johnson & Johnson, 1996).

Researches have used several theoretical frameworks to explain and predict aggressive behavior in young people (Thomas, Connor, & Scott, 2018). For a better understanding of why children tend to behave aggressively in the context of peer conflict, researchers have examined two important social-cognitive factors that might underlie children’s aggressive behavior: social goals and strategies to manage conflict, as the theory of social information processing explains (Crick & Dodge, 1994). This theory postulates that as children approach a particular social situation, they engage in several steps of processing social information (Chung & Asher, 1996). The first step involves children encoding and interpreting relevant social cues. Once social cues have been encoded and interpreted, children then select a desired outcome or goal. Following goal selection, children then decide on a specific behavioral response or strategy (Delveaux & Daniels, 2000). Therefore, this theory posits that children’s initial steps of social information processing may lead them toward responding with aggression (Erdley & Asher, 1998).

Three decades ago, Slaby and Guerra (1988) compared social information processing components of social problem solving (i.e., goal selection, solutions) and beliefs supporting aggression among three groups of adolescents: antisocial aggressive offenders, high-aggressive non-offenders in high school, and low-aggressive high school students. In this cross-sectional study of self-reported data of 144 adolescents, equally divided by sex and ranging in age from 15 to 18 years, the researchers found that high levels of aggression were associated with a low display of problem-solving skills and a high endorsement of beliefs supporting aggression. This study was one of the earliest to extend research on social information processing skills and aggression to adolescents. No studies, to our knowledge, have examined how goals and strategies differ by level of aggressive behavior in a longitudinal study.

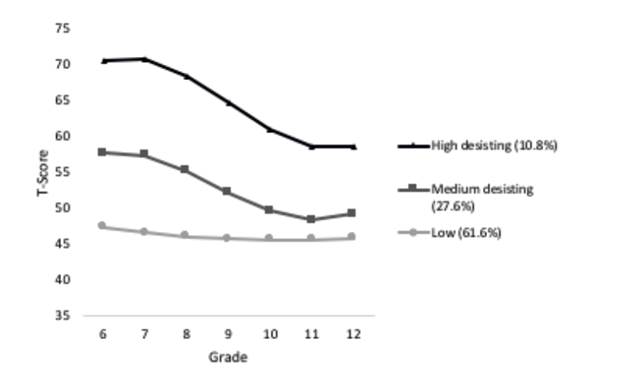

To expand the research on processing social information, the purpose of this study was to examine whether the goals and strategies students used to respond to peer conflict differed by three distinct trajectories of aggressive behavior identified in a previous longitudinal study. In 2018, based on the Healthy Teens Longitudinal Study, Orpinas and colleagues published a study describing trajectories of aggressive student behavior (Orpinas, Raczynski, Hsieh, Nahapetyan, & Horne, 2018). A cohort of students that had been randomly selected in sixth grade completed annual self-reports from sixth to twelfth grades. In addition, each year a teacher who knew the student well completed a nationally normed behavioral rating scale on student behaviors. Based on teachers’ ratings, researchers identified three distinct trajectories of aggressive student behavior: Low Aggression, Medium Desisting, and High Desisting (Figure 1). In the Low Aggression trajectory (62% of the sample), students were rated as showing low aggressive behavior in all grades with half a standard deviation (SD) below the mean of 50 from Grades 8 to 12. In the Medium Desisting trajectory (28% of sample), aggression scores started at almost 1 SD above the mean in Grade 6, but steadily declined to the average level by Grade 10. In the High Desisting trajectory (11% of sample), aggression scores started over 2 SD above the mean in Grade 6 and steadily decreased but were still almost 1 SD above the mean by Grade 12.

The present study examined whether student endorsement of goals and strategies to solve conflict would differ by trajectories of aggressive behavior. We examined three goals when faced with a conflict-maintain a good relationship, maintain personal control, and seek revenge-and six strategies to solve the conflict-verbal assertion, compromise, seek help from a teacher, mild physical aggression, verbal aggression, and yield/withdrawal. For every goal and every strategy, we graphed mean scores across time by trajectory of aggression and examined whether mean scores in Grades 6 and 12 differed significantly by aggression trajectory. We hypothesized that students in the Low Aggression trajectory would be significantly more likely to endorse the goal of maintaining a good relationship and use the strategies of verbal assertion and compromise more than youth in the other two trajectories, and that the scores of students in the Medium Desisting trajectory would be significantly higher than those in the High Desisting group. We also hypothesized that students in the High Desisting group would be significantly more likely to endorse seeking revenge and using mild physical aggression and verbal aggression to solve conflicts than youth in the Medium Desisting trajectory, and scores of this latter group would be significantly higher than youth in the Low Aggression trajectory.

Method

Participants

Data for this study were obtained from the Healthy Teens Longitudinal Study. In the previous study, researchers identified three trajectories of aggression based on teacher ratings collected annually from Grade 6 to 12 (Orpinas et al., 2018). A randomly-selected group of sixth graders from nine middle schools located in Northeast Georgia, USA, were invited to participate. In sixth grade, 745 students (79% response rate) enrolled in the study and 624 (84% response rate) re-consented to continue participation in ninth grade. Every year, students completed a self-reported survey and teachers completed a nationally normed teacher rating scale measuring student behavior. In the development of the aggression trajectories, four records were excluded due to missing teacher data. Because a few students did not complete the Goals and Strategies scale, the final sample for the sixth-grade analysis was 601 and for the twelfth-grade analysis was 582. The final sample was evenly divided by gender (52% boys). Approximately half of the students were self-described as White (48%), followed by Black (36%), and Latino (12%); the remaining 4% self-identified as Asian, multiracial or other. Mean scores of the goals and strategies in Grade 6 did not differ significantly between students who did not re-consent to continue in the Healthy Teens Longitudinal Study from those who did re-consent.

Teacher Ratings.

The previous study used the aggression subscale of the adolescent version of the nationally normed Behavior Assessment System for Children-Teacher Rating Scales (BASC-TRS) to identify trajectories of student aggressive behavior (Orpinas et al., 2018). Aggression (14 items, alpha = 0.95) refers to the ‘‘tendency to act in a hostile manner (either verbal or physical) that is threatening to others’’(Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992, p. 48). Examples of aggressive behaviors are threatening to hurt, hitting, bullying, and teasing others. Teachers rated students using the following response categories: Never (0), Sometimes (1), Often (2), and Almost Always (3). Values were standardized to t scores using the national norm group with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 provided in the BASC manual based on national scores.

Student self-reported scales.

The Goals and Strategies scales were based on a measure originally developed by Hopmeyer and Asher (1997). For this present study, the Goals and Strategies measure consisted of four hypothetical vignettes that assess the student’s responses to conflict situations with peers of the same gender as the respondent, including both what the student desires to accomplish or attain (i.e., goal) and the student’s strategies for dealing with the situation. The vignettes were written using second person pronouns, as the following example:

You are going to a performance in the auditorium. You and another boy/girl both want to sit in the front row near several of your friends. There is only one chair left in the front row. You get to the chair first and sit down. The other boy/girl comes up to you and says, “That’s my seat.”

For each scenario, respondents were asked to rate their agreement with three statements about their goals in that situation, by responding to the question “What would be your goal?” These statements were: maintaining a good relationship (i.e., “My goal would be trying to get along with this student”), maintaining personal control (i.e., “My goal would be trying not to let him/her push me around”), and seeking revenge (i.e., “My goal would be trying to get back at him/her for what he/she just did”). Next, students responded to the question “What would you do?” by indicating the likelihood of using each of the six strategies. The strategies were verbal assertion (i.e., “I would tell him/her I’m sitting here and he/she can sit in the front row another time”), compromise (i.e., “I would suggest that we each use the chair for half of the performance”), seek help from a teacher (i.e., “I would ask a teacher for help”), mild physical aggression (i.e., “I would push him/her away from the chair”), verbal aggression (i.e., “I would call him/her a mean name”), and yield/withdrawal (i.e., “I would let him/her use the chair”).

Response categories for goals ranged from really disagree (1) to really agree (5). Response categories for strategies ranged from I definitely would not do this (1) to I definitely would do this (5). Cronbach’s alpha scores for goals ranged between 0.84 and 0.95 and for strategies ranged between 0.73 and 0.99, across subscales and grade levels. All scales were computed as the average across the four vignettes, with higher scores indicating a stronger endorsement of that goal or greater likelihood of engaging in that strategy.

Procedure

Every year, towards the end of the academic year (between March and April 2003 to 2009), trained research assistants collected data in middle schools using a computer-assisted survey interview (CASI) that enabled students to see and hear each survey question. High school students completed the survey online using a computer located in their school’s media center. Research assistants visited all students who dropped out of school at their home or another convenient location to complete a paper-based survey. All research assistants had received university certification in human subjects’ research and followed strict protocols to maintain confidentiality of the data.

In each grade level, a core academic teacher completed a standardized rating of students. Research staff inquired as to whether the teacher knew the student well enough to complete the rating. Parents provided parental permission, students assented, and teachers consented to participate in the study. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all research procedures.

Data Analysis

To visualize changes over time, we plotted the mean scores of the three goals (Figure 2a, 2b, and 2c) and the six strategies (Figures 3a, 3b, 3c and 4a, 4b, 4c) for each grade level by aggression trajectory. Next, to examine whether student self-reports of goals and strategies differed by trajectories of student aggressive behavior, we used analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s HSD (Honest Significant Difference) for pairwise comparisons. We selected two grade levels to conduct this analysis, Grades 6 and 12. These two grade levels are the first and last years that students completed the assessments and they represent very different stages of psychological development. In addition, at Grade 6, the three aggression trajectories had the biggest difference, and at Grade 12 the smallest. All analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 24.

Results

Goals

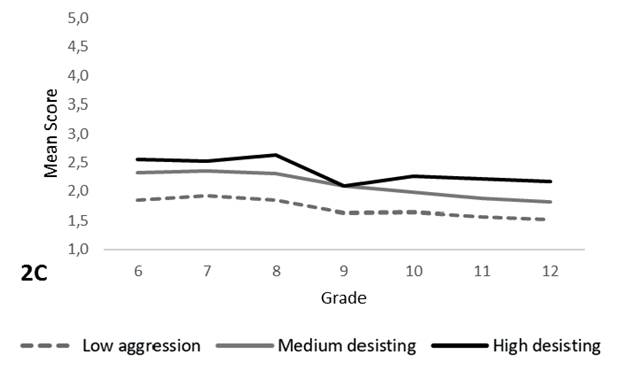

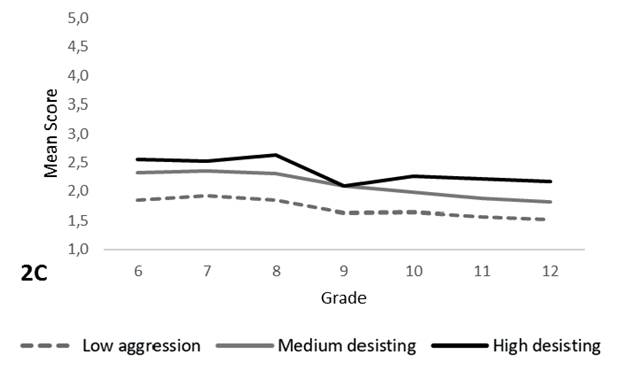

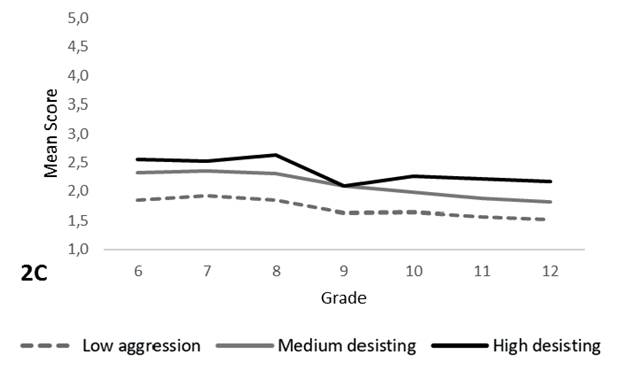

Mean scores of student self-reported goals were fairly stable from Grade 6 to 12 for all aggression trajectories, with the lowest endorsement of seeking revenge (Figure 2c, Table 1). For maintaining a good relationship, mean scores were slightly higher in Grade 6 than 12 for the Medium Desisting and High Desisting groups. For maintaining personal control and seeking revenge, overall mean scores, as well as scores for each trajectory, were slightly higher in Grade 6 than 12.

Figure 2 A. Mean scores of self-reported goal “maintain a good relationship in handling conflict” for aggression trajectories-Grades 6 to 12. B. Mean scores of self-reported goal “maintain personal control in handling conflict” for aggression trajectories-Grades 6 to 12. C. Mean scores of self-reported goal “seek revenge in handling conflict” for aggression trajectories-Grades 6 to 12.

Table 1 Comparison of mean scores of goals and strategies among teacher-rated aggression trajectories

Note. Tukey’s HSD was used for multiple comparisons, with p < 0.05.

Source: own elaboration.

At Grade 6 and at Grade 12, youth in the Low Aggression group reported significantly higher scores in the goal of maintaining a good relationship and significantly lower scores in seeking revenge than youth in the other aggression groups. Only for seeking revenge in Grade 12, the Low Aggression group reported significantly lower scores than the Medium Desisting, which was significantly lower than the High Desisting group. Maintaining personal control did not differ by trajectory groups at either grade level (Table 1).

Strategies

Mean scores of self-reported student strategies were fairly stable from Grades 6 to 12 for all aggression trajectories (Figures 3a, 3b, 3c and 4a, 4b, 4c, Table 1), with the highest endorsement of verbal assertion and compromise for all groups. As shown on Table 1, for all aggression trajectories, mean scores of all strategies slightly decreased from Grades 6 to 12. Mild physical aggression and verbal aggression increased during the middle school years, that is, from Grades 6 to 8.

Figure 3 A. Mean scores of self-reported strategy “verbal assertion in handling conflict” for aggression trajectories-Grades 6 to 12. B. Mean scores of self-reported strategy “compromise in handling conflict” for aggression trajectories-Grades 6 to 12. C. Mean scores of self-reported strategy “seek help from a teacher in handling conflict” for aggression trajectories-Grades 6 to 12. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 4 A. Mean scores of self-reported strategy “mild physical aggression in handling conflict” for aggression trajectories-Grades 6 to 12. B. Mean scores of self-reported strategy “verbal aggression in handling conflict” for aggression trajectories-Grades 6 to 12. C. Mean scores of self-reported strategy “yield-withdrawal in handling conflict” for aggression trajectories-Grades 6 to 12. Source: own elaboration.

Of the six strategies, the three most positive ones to solve a conflict are verbal assertion, compromise, and seek help from a teacher. For verbal assertion, both in Grades 6 and 12, youth in the Low Aggression group had significantly higher scores than youth in the High Desisting aggression group. For compromise in Grades 6, youth in the Low Aggression group had significantly higher scores than youth in the Medium Desisting and in the High Desisting aggression groups. In Grade 12, youth in the Low Aggression group had significantly higher scores than youth in the High Desisting aggression group. The three aggression groups did not differ in seeking help from a teacher (Table 1).

The two aggressive strategies were mild physical aggression and verbal aggression. For both of these strategies, in Grades 6 and 12, youth in the Low Aggression group had significantly lower scores than youth in the Medium Desisting and in the High Desisting aggression groups (Table 1).

The final strategy was to yield or withdraw from the conflict. Only in Grade 12, youth in the Low Aggression group had significantly higher scores than youth in the Medium Desisting aggression group (Table 1).

Discussion

Examining trajectories of adolescent behavior is important to understand the pathways that lead students to behave aggressively toward their peers and ultimately aid in developing programs to prevent violence. This study examined whether the goals and strategies students use to respond to peer conflict in sixth and twelfth grades differed among three distinct trajectories of student aggressive behavior: Low Aggression, Medium Desisting, and High Desisting. The present study advances research on adolescent peer conflict and aggressive behavior in two key ways. First, few studies have examined adolescents’ goals and strategies in peer conflict situations. Most of the research on peer conflict focuses primarily on early childhood. Given that adolescence is a unique period of development, more research is needed to understand how youth solve peer conflict. Second, this longitudinal study is the first to examine how goals and strategies differ by level of student aggressive behavior over a 7-year period. The study has valuable implications for developing school programs to prevent violence and enhance a positive school climate.

First, as hypothesized, youth in the Low Aggression trajectory endorsed the most positive goal-maintain a good relationship-and the most positive strategies to resolve conflict: verbal assertion and compromise. These findings are consistent with research and theory indicating that adolescents who are less aggressive than their peers are more likely to use prosocial strategies in their response to peer conflict situations (Coie et al., 1990; Crick & Dodge, 1994; Johnson & Johnson, 1996). For example, Slaby and Guerra (1988) found that low-aggressive students generated more alternative solutions than their highly aggressive counterparts. Also, the non-aggressive adolescents of their study simultaneously valued maintaining friendships and encouraging fairness, while at the same time behaving assertively. Researchers have suggested that adolescents who are prosocial are generally good problem solvers, considerate, and most importantly, tend to solve conflicts without aggression (Eisenberg, Carlo, Murphy, & Court, 1995; Marsh, Serafica, & Barenboim, 1981). Therefore, these students would generate more effective solutions to peer conflicts than youth in other trajectory groups. Slaby and Guerra (1988) found that all students tended to select effective solutions in response to the hypothetical social conflict situations. However, low-aggressive students were more likely than aggressive offenders to select effective solutions.

Second, as hypothesized, youth in the two higher aggression trajectories had stronger support for seeking revenge and using physical and verbal aggression to solve conflict. These findings are consistent with the theory of social information processing and previous research on children suggesting that aggressive children tend to access social strategies that are more aggressive and less prosocial than nonaggressive children (Asarnow & Callan, 1985; Crick & Dodge, 1994; Deluty, 1981; Pettit, Dodge, & Brown, 1988; Quiggle, Garber, Panak, & Dodge, 1992; Richard & Dodge, 1982; Winstok, 2009). Children’s use of aggressive social goals increases the likelihood that they will respond aggressively in their social interactions (Crick & Dodge, 1994).

Third, contrary to our hypothesis, the study did not support differences between the two trajectories of higher aggression. Thus, youth in the Medium Desisting and High Desisting trajectory groups shared common goals and strategies for dealing with conflict situations with peers. Although these two groups differed in their level of aggressive behavior, it may be that these students are more similar than different, especially with how they approach peer conflict. Another possible explanation is that cognitive strategies to solve conflict are just one dimension of adolescent behavior. Other risk factors related to peers, family and neighborhood could be influencing youth differently in these two trajectories of aggression.

Fourth, endorsement of seeking help from a teacher did not vary by aggression group or by grade level. Perhaps seeking help from a teacher in peer conflict is perceived by some adolescents as a sign of weakness or a violation of the norm that adolescents should solve conflict among peers by themselves. However, Aceves, Hinshaw, Mendoza-Denton, and Page-Gould (2010) concluded that high school students do ask for help from a teacher when they perceive teachers as good problem solvers. The overall low endorsement of asking teachers for help may reflect a perceived school environment in which students do not trust how teachers handle problems when they arise.

Fifth, endorsement of yield/withdrawal was higher among twelfth graders in the Low Aggression group. It is possible that these good students, at the end of their high school career, are not willing to fight over minor conflicts. Additionally, researchers have found that conflict solving strategies tend to become more sophisticated with age (Laursen, Finkelstein, & Betts, 2001; Noakes & Rinaldi, 2006). The cognitive advances made by adolescents may also cause them to consider passive strategies as a mature way to mitigate the intensity of conflict or avoid further escalation of conflict. For example, Noakes and Rinaldi (2006) found that eighth graders were able to come up with more cooperative and effective strategies than younger students. These results have important implication for schools, particularly middle schools.

Finally, this study combined teacher evaluations of aggressive behavior over time with students’ self-reports. Although every informant has a possible bias, teacher evaluations of aggressive behavior are probably the most reliable, as these behaviors are observable and teachers are less likely than students to over or under report them. Researchers have found modest associations between teacher ratings and student self-reports (Lohre, Lydersen, Paulsen, Maehle, & Vatten, 2011; van der Ende, Verhulst, & Tiemeier, 2012). However, the results from our study were in the expected direction, giving some validity to both teacher ratings and students reports.

This study has some limitations. Because the results were based on data collected longitudinally; a few participants were lost to follow-up. However, the sample was large and the methodology to calculate the trajectories over time is very robust to missing values. This study used teacher ratings to measure student aggressive behavior, which is both a strength (as discussed previously) and a limitation. Even though the selected teachers knew the students well, middle and high school students rotate through several classrooms; thus, teachers spend less time with students than in elementary school. Teachers may not observe critical moments in the interaction of students, such as recess periods or breaks between classes, where peer aggression and victimization may increase due to limited adult supervision leading to fewer consequences (Astor & Meyer, 2001; Leff, Costigan, & Power, 2004). The BASC only measures a combination of physical and verbal aggression. More research is needed on relational, indirect, or electronic aggression; however, it is harder for teachers to observe these less overt forms of aggression. Similarly, more research is needed on conflicts that are particularly challenging among adolescents, such as those within romantic relationships, electronic media, and intergroup conflicts. Given that the assessment of goals and strategies were based on students’ self-reports, the findings are subject to the usual validity concerns and possible social desirability. Finally, the study sample was obtained from one region of Georgia, and the results may not be generalizable to adolescents in other areas of the United States or in other countries. Yet, the sample was diverse (demographic characteristics of students, urban and rural location of school), which strengthens the findings.

To conclude, this study contributes to the understanding of the goals and strategies adolescents use to respond to peer conflict and how they differ by level of student aggressive behavior. In our study, goals and strategies were fairly stable over time for all trajectories; thus, prevention programs must start early, perhaps in elementary school and continue in middle and high school. As hypothesized, youth in the Low Aggression trajectory endorsed the most prosocial goals and strategies to solve conflict, while youth in the two higher aggression trajectories endorsed the most aggressive. These findings highlight the importance of developing school prevention programs that target social-cognitive factors affecting students’ behavior in peer conflict situations to prevent violence among students and to enhance a positive school climate.

School-based prevention programs explicitly aimed at social-cognitive factors may be vital in helping students resolve everyday conflicts in constructive and prosocial ways that do not impair friendships or disrupt classmates’ interactions. To create a school climate in which peer conflicts occur infrequently and students treat one another with respect, school personnel should take a proactive approach to improving social-cognitive skills. Students should learn problem-solving steps that stimulate respectful conversations and that satisfy the goals of their peers as well as their own. A positive school climate is inviting and energizing, one where all forms of peer aggression are taken seriously and addressed effectively to ensure that each student feels safe and protected.