Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Universitas Psychologica

versión impresa ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. v.8 n.3 Bogotá sep./dic. 2009

Conceptualizations of Forgiveness: a Latin America-Western Europe Comparison*

Concepciones de perdón: una comparación entre Latinoamérica y Europa Occidental

ADRIANA BAGNULO

Université de Toulouse-le Mirail, Toulouse, Francia

MARÍA TERESA MUÑOZ-SASTRE

Université de Toulouse-le Mirail, Toulouse, Francia

ETIENNE MULLET**

Institute of Advanced Studies (EPHE), Paris, France

* Research article. This work was supported by the "Université de Toulouse", the CERPP and the UMR 5263 (EPHE, CNRS and Mirail University).

** Etienne Mullet, PhD, is director of research at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Paris, France. Corresponding address: Quefes 17 bis, F-31830 Plaisance du Touch, France. Correo electrónico: etienne.mullet@wanadoo.fr

Recibido: diciembre 6 de 2008 | Revisado: marzo 14 de 2009 | Aceptado: marzo 20 de 2009

RESUMEN

Se examinaron las concepciones de perdón en dos muestras de participantes latinoamericanos y europeos. En ambas se encontró la misma estructura básica de cuatro factores de las concepciones: cambio de idea, proceso más que diádico, fomento del arrepentimiento y comportamiento inmoral. Los latinoamericanos estuvieron más de acuerdo con la idea de que se puede extender el perdón a personas desconocidas o fallecidas, y que el perdón se puede ofrecer de parte de familiares fallecidos. En ambas muestras se encontraron desacuerdos sustanciales sobre la naturaleza psicológica del perdón (un cambio de idea), y una gran proporción de participantes estuvieron en desacuerdo con la idea de que puede fomentar el arrepentimiento del agresor. Sin embargo, la mayoría de participantes compartieron la idea de que el perdón no es inmoral. Se recomienda definir con precisión el concepto de perdón antes de introducirlo en contextos terapéuticos y no terapéuticos, y no esperar que todo el mundo concuerde con la definición.

Palabras clave autores Concepto, perdón, Uruguay. Francia.

Palabras clave descriptores Conceptualización, perdón, solución de conflictos, solución de conflictos, Europa occidental, Uruguay.

ABSTRACT

Conceptualizations of forgiveness were examined in two samples of Latin American and Western European participants. In both samples the same basic four-factor structure of conceptualizations was found: Change of Heart, More than Dyadic Process, Encourages Repentance, and Immoral Behavior. Latin Americans agreed more than Western Europeans with the idea that forgiveness is extensible to unknown or deceased people, thus it can be offered on behalf of deceased relatives. In both samples, substantial disagreements were found about the psychological nature of forgiveness (a change of heart), and a large proportion of participants disagreed with the idea that it may encourage the offender's repentance. However, most participants, agreed with the basic idea that forgiveness is not immoral. It is thus recommended, to precisely define the concept of forgiveness before introducing it in therapeutic (and non-therapeutic) settings, and not to expect that everyone would agree with the proposed definition.

Key words authors Conceptualizations, Forgiveness, Uruguay, France.

Key words plus Conceptualization, Forgiveness, Conflict Management, Conflict Management, Europe, Western, Uruguay.

Forgiveness is a central topic in everyday life (Worthington, 2005). From the personal level, to the family level, to the community level, to the international level, the quality of our relationships with others is largely determined by the conceptualizations we hold regarding forgiveness. These conceptualizations have potentially important repercussions on the way we conceive family life (e.g., parenting), behavior at the workplace (e.g., in case of conflict with colleagues), the functioning of institutions (e.g., the nature of the justice system), international politics (e.g., truth commissions), and psychological counseling (e.g., use of forgiveness in therapy). The present study was aimed at examining the way in which people conceptualize forgiveness, and the differences in conceptualization that may be linked to culture.

Why study the conceptualizations of forgiveness among people?

Examining the way people conceptualize forgiveness is important for practical as well as theoretical reasons. "The beliefs that you hold about forgiveness open or close possibilities for you, determine your willingness to forgive, and, as a result, profoundly influence the emotional tone of your life" (Casarjian, 1992, p .12). In other words, the conceptualizations you hold about forgiveness may have important repercussions on your well-being (Worthington & Sherer, 2004). It is because forgiveness appeared to be conceptualized in so many different, and sometimes antagonist, ways that Enright and Fitzgibbons (2000) recommended that before applying their process model of forgiveness in therapeutic sessions, a clear definition of forgiveness be given to the potential clients (see also, Malcolm, Warwar & Greenberg, 2005; Gordon, Baucom & Snyder, 2005).

Suppose that you have offended someone and that you are willing to be forgiven by this person. You offer apologies for the harm done and you request forgiveness. The way this person reacts to the apologies and to the request for forgiveness will (largely, although not only) depend on the way she/he conceptualizes forgiveness. If this person believes that forgiving is nothing more than agreeing with the offender for the harm done or that forgiving strongly encourages the offender to still more harmfully behave in the future, then, despite your efforts, this person will obstinately refuse to grant you forgiveness. If you are not aware that the person you have offended may conceptualize forgiveness in a way that is different from yours, you are at risk of not understanding this person's reaction, and the relationship with him/her will tend to get worse. If, on the contrary, your counselor told you that sometimes people confuse forgiving and pardoning, then you will be less surprised by this person's reaction, and you will be better prepared to reformulate your apologies, insisting more on your responsibility in what happened, and on your determination to never do it again.

If, in another example, this person believes that granting forgiveness is the best way to publicly humiliate an offender, it is highly likely that you will be "granted forgiveness" but this way of forgiving will only be the prelude to countless misunderstandings between him/her and you in the future. If you are not aware that some people conceptualize forgiveness in a way that is different from yours, you are at risk of considering his/her "forgiveness" as true forgiveness and you are at risk of not understanding why his/her subsequent behavior towards you is so rude or disdainful. The relationship with this person will get worse. If, on the contrary, your counselor told you that some people conceptualize forgiveness as a way to humiliate the offender, then you are more likely to correctly understand the reasons of this strange behavior, and you will be prepared to approach the problem in another way.

In these concrete examples, both for requesting and granting forgiveness, knowing (a) how people in general conceptualize forgiveness (e.g., perpetuation of harm doing or humiliation of the offender), and (b) more importantly, to what extent people's conceptualizations differ from another can be very helpful, both for clients and counselors. As an example, if a majority of people conceptualizes forgiveness as having nothing to do with humiliating the offender, and if the divergences on this point are minimal, then one is led to think that the problem evoked above (in the second example) is an unlikely occurrence. By contrast, if extreme divergences in conceptualization of forgiveness (in terms of offender's humiliation) are the rule, one is led to be prudent when being granted forgiveness. In such a case, it may be advisable to come to an agreement beforehand with the forgiver on the meaning of forgiveness.

The situations presented above do not exhaust all scenarios in which conceptualizations of forgiveness impact daily life. Multiple other examples illustrate this point. Suppose you have been the victim of a collective offense; that is, an offense perpetrated by a like-minded group of people. If you conceptualize forgiveness as a process that can only take place between two people; that is, if you have a strictly dyadic concept of forgiveness, you will experience difficulties with the idea of forgiving a whole group of people. Also, you possibly will not see much sense in the head of the group requesting forgiveness on behalf of the whole group. If, however, the way you conceptualize forgiveness includes other social configurations than the dyadic offender-offended one, you will be able to begin working hard at forgiving the group for the collective harm done. Therefore, before encouraging groups to offer collective apologies to individuals for a harm done, or encouraging individuals to try forgiving collective offenses, it is important for a counselor to know how most people tend to conceptualize forgiveness.

The present study

Conceptualizations of forgiveness have recently been studied by Mullet, Girard, and Bakhshi (2004). These authors examined the extent to which people agree with conceptualizations of forgiveness encountered in literature, notably that (a) forgiveness supposes the replacement of negative emotions towards the offender by positive emotions, (b) forgiveness is a process that can only take place between an offender and offended who know one another, and (c) forgiveness is not a process that devaluates the forgiven but instead encourages him/her to behave better in the future. More than one thousand Western European persons participated in the study. Four conceptualization factors were identified: Change of Heart, More-Than-Dyadic Process, Encourages Repentance, and Immoral Behavior. (The last two factors were reminiscent of factors found by Konstam, Marx, Schurer, Harrington, Emerson Lombardo & Deveney, 2000, among psychotherapists and called Positive Forgiveness and Negative Forgiveness).

Only a minority of participants agreed with the idea that forgiving supposes a change of heart (regaining affection or sympathy towards the offender), and with the idea that forgiveness can encourage the offender's repentance. More participants, however, agreed with the ideas that the forgiver can be someone other than the offended (but with a close relationship to the offended) and that the forgiven can be an unknown offender or an abstract institution. Very few participants agreed with the idea that forgiveness is immoral.

The four factor structure suggested by Mullet et al. (2004) has proven to have cross-cultural value: The same factors have been evidenced in a sample of Congolese adults (Kadima Kadiangandu, Gauché, Vinsonneau & Mullet, 2007). In addition, the findings supported the view that in the Congolese (collectivistic) culture, forgiveness was mainly conceived as an "interpersonal" construct, although in the French (individualistic) culture, it was mainly conceived as an "intrapersonal" process. The Congolese more than the French conceived forgiveness as aimed at reconciling with the offender and extensible to people outside the offended-offender dyad.

The present study was aimed at testing further the cultural robustness of the structure suggested by Mullet et al. (2004). Data from a sample of participants from a Latin American country (Uruguay) were gathered and compared with new data gathered in Western Europe in terms of overall structure, means and standard deviations. Although, from a cultural viewpoint, both countries have in common a Western (largely Christian) cultural/spiritual heritage, they differ regarding individualism-collectivism. Uruguay, and Latin America in general, may be considered as more collectivistic societies than France and Western Europe (although not so collectivistic than Congo; Hofstede, 2001).

Our first hypothesis was that, owing to their common spiritual heritage, Latin American participants and Western European participants should show the same basic structure of conceptualizations. In other words, the four-factor model evidenced in the studies by Mullet et al. (2004) and Kadima Kadiangandu et al. (2007) should also be found in the Latin American sample.

Our other hypotheses were based on the consideration that forgiveness may be viewed differently in collectivistic societies and in individualistic societies (Kadima Kadiangandu et al., 2007; Sandage & Williamson, 2005; see also Neto, Pinto & Mullet, 2007). The second hypothesis was that differences between the Latin Americans and the Western Europeans regarding the Change of Heart factor should be evidenced. This factor expresses the idea of restoration of previous relationships. A typical item was: "To forgive someone necessarily means to start feeling affection towards the person again". The precise hypothesis was that Uruguayans' score on this factor should, as what was observed in the Congolese sample, be higher than French's scores. The third hypothesis was that the endorsement of the items linked with the More-Than-Dyadic Process factor should, as what was observed in the Congolese sample, be higher among the Uruguayans than among the French.

Method Participants

The participants came from the Montevideo region of Uruguay and from the Midi-Pyrénées region of France. There were 188 Uruguayan participants (116 females and 72 males) and 258 French participants (134 females and 124 males). Age ranged from 17 to 84. Mean ages were 41.51 (SD = 13.95) for Uruguayans and 40.05 (SD = 14.06) for French. Fourteen percent of the participants declared that they attend Church on a regular basis, 40% declared that they believe in God but do not attend Church, and 47% of the participants declared that they did not believe in God. The participation rates were 63% and 75% for the Uruguayans and the French respectively (in other words, originally 300 Uruguayans and 400 French were contacted for participation). The data was gathered in 2003 (for Uruguay) and in 2004 (for France). The samples can be considered as reasonably similar.

Material

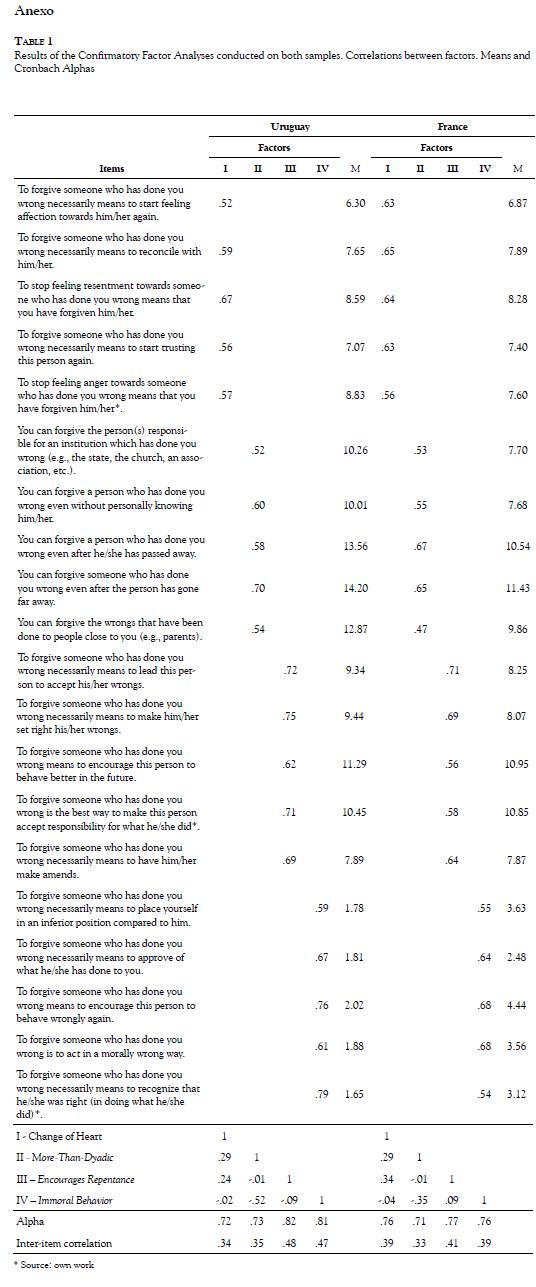

We used a slightly modified version of the Conceptualization of Forgiveness Questionnaire by Mullet et al. (2004), which contained 20 items (see Table 1). A pilot study was conducted on ten Uruguayan participants. As for three items from the original questionnaire there was no variance in the responses, these items were rephrased for better clarity with the participants' help. A 17-cm scale was placed after each sentence. This was chosen in order to provide enough latitude in the responses (especially in case the answers are at one or the other extreme of the scale). The two extremes of the scales were labeled "completely disagree" and "completely agree".

Procedure

The participants responded individually at home or at the university (depending on what was most convenient for each participant). They were asked to read each item in the questionnaires -expressing feelings or beliefs about forgiveness- and rate the extent to which they agreed with each item on the 17-cm scale. In rare cases, when the participants said that they did not understand an item, the item was individually explained to them (in such a way that the responses were not influenced).

Results

Each participant's rating was converted to a numerical value expressing the distance (1 to 17) between the point on the response scale and the left anchor, which served as the origin. These numerical values were then subjected to graphical and statistical analyses. A confirmatory factor analysis was first conducted on the French sample. The model tested was the correlated four-factor model proposed by Mullet et al. (2004). No correlation between error terms was allowed. All path coefficients were significant, and the values of the fit indices were satisfactory (GFI = 0.89, CFI = 0.88, ChiVdf = 1.90, RMR = 0.07, RMSEA = 0.06 [0.04-0.07]). A second confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the Uruguayan sample using the same model. In this case also, all path coefficients were significant (GFI = 0.88, CFI = 0.91, Chi2/df = 1.52, RMR = 0.07, RMSEA = 0.05 [.04-.06]). Table 1 shows the results of the CFAs and the Cronbach alpha values for each sample. Computed over the two samples alpha values ranged from 0.69 to 0.80.

For each factor, a mean score was computed by averaging the five corresponding item scores. A series of three ANOVAs with a Gender x Country, 2 x 2 design was conducted on these mean scores. A series of ANCOVAs with a Religious Involvement, 3 design was conducted on the mean score, with Country and Gender as the covariant variables.

Regarding the Change of heart factor, the Uruguayan score was not significantly different from the French score. The gender effect was, however, significant, F(1, 442) = 7.49, p < .001, rfp = 0.02. Women's score (M = 8.07, SD = 3.97) was higher than men's score (M = 7.07, SD = 3.50).

Regarding the More-Than-Dyadic Process factor, the Uruguayan score (M = 12.17, SD = 3.83) was significantly higher than the French score (M = 9.43, SD = 3.61), F(1, 442) = 56.38, p < 0.001, r|2p = 0.11. Also, the Religious involvement factor had a significant effect, F(2, 430) = 11.16, p < 0.001. Participants who attended Church on a regular basis had higher scores (12.59) than participants who believed in God but did not attend Church (10.95) and participants who did not believe in God (9.68). A subsequent ANOVA with a Country x Religious involvement design showed that the interaction was not significant.

Regarding the Encourages Repentance factor, the difference between the Uruguayans and the French was not significant (Overall M = 9.60, SD = 3.99). However, regarding Immoral Behavior, the difference between the Uruguayans (M = 1.85, SD = 1.88) and the French (M = 3.46, SD = 2.79) was significant, F (1, 442) = 46.05, p < 0.001, []2p = 0.09. Namely, the Uruguayan score was lower than the French score. Finally, correlations between factor scores and age were not significant.

Discussion

The present study was aimed at examining the conceptualizations of forgiveness in two samples of Latin American and Western European participants. The first hypothesis was that the same basic conceptualizations structure should be found in both samples. This is what was observed. The same four factors as the one that were evidenced by Mullet et al. (2004) and by Kadima et al. (2007) were found: Change of Heart, More than Dyadic Process, Encourages Repentance, and Immoral Behavior.

The second hypothesis was that a difference between the Latin Americans and the Western Europeans should be found regarding the Change of Heart factor. This was not observed. Both scores were close to the middle of the agreement scale; in other words, in both countries, considerable disagreement exists on whether forgiveness implies a change of heart towards the offender or that a change of heart towards the offender implies forgiveness: 90% of the responses were between 2 and 12 (on a 1-17 scale). Women, more than men, endorsed this conceptualization; however, the gender difference was weak compared to the vast variety of individual differences on this point.

This result contrasts with the findings by Kadima Kadiangandu et al. (2007). It also contrasts with the findings by Denton and Martin (1998) which showed that a strong majority of clinical psychologists agreed with the idea that forgiveness implies a change of heart. This result is, however, consistent with findings by Kearns and Fincham (2004) which showed, in a prototype analysis, that "having sympathy for the offender" was quoted as a feature of forgiveness by only 9% of their participants and that the centrality rating of this feature was only about 5 on an 1-8 centrality scale (see also, Kanz, 2000). This result is also consistent with Andrews' (2000) findings showing that for many people, a true change of heart may depend on further communication between the wronged and the wrongdoer.

It may thus be helpful for counselors to keep in mind that substantial disagreements regarding the psychological nature of forgiveness are to be expected among Latin American people as well as among Western European people in daily life. Namely, only a minority of persons seems to believe that forgiveness would involve regaining affection or sympathy towards the offender. As a result, when forgiven by someone, it may be preferable not to expect too much from the forgiver, at least initially.

The third hypothesis was that a difference between Latin Americans and Western Europeans should be found regarding the More than Dyadic Process factor. This is what was observed. The country effect was strong and in the hypothesized direction. It was also found that the more religious participants had a more favorable position on this conceptualization that the less religious participants. In other words, more than the others, they endorsed the idea that forgiveness could be extensible to the persons responsible for the state, Church, or an association, and extensible to personally unknown or deceased individuals, and can be offered on behalf of deceased close relatives. The country and religious involvement were independent factors: in other words, culture (collectivism-individualism) and religious orientation added their effect.

In the Latin American culture examined here, as in the Congolese culture examined by Kadima Kadiangandu et al. (2007), the identities of the possible forgivers and forgiven persons are broader than the ones usually considered in the literature.

The forgiver can be the offended person or someone in close relationship with him/her (e.g., a family member). The forgiven party can be a known offender but also an unknown offender or an abstract institution (e.g., Church). In the Western European sample, by contrast, one person out of four strongly believed that forgiveness could only occur between two people knowing each other. Consequently, for these individuals, it may be not easy to consider forgiving an institution or third-party forgiveness (see also, Denton & Martin, 1998). Our result is also consistent with Gassin's (2001) view that in more collectivistic societies, community actions are frequently undertaken in order to facilitate forgiveness.

Some other findings deserve comments. Regarding the Encourages Repentance factor, both scores were close to the middle of the agreement scale; that is, considerable disagreement exists in both cultures on whether forgiveness may improve the offender's behavior (90% of the responses were distributed between 4 and 14). Namely, about 40% of the participants in both samples clearly disagreed with the idea that forgiveness can have positive consequences on the forgiven. Thus, counselors must be aware that among their clients, and independently of their culture, considerable differences exist regarding the idea that forgiveness would set a good example for others, and that as a result of forgiveness, they become better people, acknowledge their wrongs, regret their acts, and repair their faults.

Regarding the Immoral Behavior factor, a difference between Latin Americans and Western Europeans was found but the country effect was weaker than for the More than Dyadic Process factor. In fact, the effect was moderate: the Uruguayans, more than the French, disagreed with the idea that forgiveness is bad; that is, that forgiveness humiliates the offender or the offended, and that forgiveness encourages the offender to continue with his/her bad behavior. However, few disagreements regarding this issue are to be expected between people in daily life; mainly because the idea that "forgiveness is moral" seems to be accepted as part of everyday general beliefs and commonsense.

This result is consistent with findings by Kearns and Fincham (2004) which showed that "a sign of weakness" was quoted as a feature of forgiveness by only 8% of their participants and that the centrality rating of this feature was only about 3 on an 1-8 centrality scale (see also, Kanz, 2000).

It can be recommended, before introducing the concept of forgiveness in therapeutic (and non-therapeutic) settings, to precisely define it, and not to expect that everyone will accept the proposed definition (Enright, Eastin, Golden, Sarinopoulos & Freedman, 1992). If most people agree with the common sense idea that forgiveness is not immoral, a substantial proportion, however, would possibly resist the idea that it entails a change of heart towards the offender and encourages the offender's repentance (see also Wuthnow, 2000). This resistance may be linked to many personal factors, not only culture, as in the present study, but also psychosocial development (Romig & Veenstra, 1998), personality style (Mullet, Neto & Rivière, 2005), psychopathology (Muñoz Sastre, Vinsonneau, Chabrol & Mullet, 2005), or professional specialization (Denton & Martin, 1998). The items used in the present study, and the structure they form, may be offered as an intellectual tool for clinicians from diverse countries in need of better understanding the conceptualizations of forgiveness in their national clients as well as in their foreign clients.

References

Andrew, M. (2000). Forgiveness in context. Journal of Moral Education, 29, 75-86. [ Links ]

Casarjian, R. (1992). Forgiveness: A bold choice for a peaceful heart. New York: Bantam Books. [ Links ]

Denton, R. T & Martin, M. W. (1998). Defining forgiveness: An empirical exploration of process and role. American Journal of Family Therapy, 26, 281-292. [ Links ]

Enright, R. D., Eastin, D. L., Golden, S., Sarinopoulos, I. & Freedman, S. (1992). Interpersonal forgiveness within the helping professions: An attempt to resolve differences of opinion. Counseling and Values, 36, 84-101. [ Links ]

Enright, R. D. & Fitzgibbons, R. P. (2000). Helping clientsn forgive: An empirical guide for resolving anger and restoring hope. Washington: A.PA. [ Links ]

Gassin, E. A. (2001). Interpersonal forgiveness from an Eastern Orthodox perspective. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 29, 187-200. [ Links ]

Gordon, K. C., Baucom, D. H. & Snyder, D. K. (2005). Forgiveness in couples: Divorce, infidelity, and couples therapy. In E.Worthington (Ed.), Handbook of Forgiveness (pp. 407-422). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage. [ Links ]

Kadima Kadiangandu, J., Gauché, M., Vinsonneau, G. & Mullet, E. (2007). Conceptualizations of forgiveness: Collectivist-Congolese versus Individualist-French viewpoints. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38, 432-437. [ Links ]

Kanz, J. E. (2000). How do people conceptualize and use forgiveness? The Forgiveness Attitude Questionnaire. Counseling and Values, 44, 174-189. [ Links ]

Kearns, J. N. & Fincham, F. D. (2004). A prototype analysis of forgiveness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 838-855. [ Links ]

Konstam, V., Marx, F., Schurer, J., Harrington, A., Emerson Lombardo, N. & Deveney, S. (2000). Forgiving: What mental health counselors are telling us. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 22, 253-267. [ Links ]

Malcolm, W. M., Warwar, S. H. & Greenberg, L. S. (2005). Facilitating forgiveness in individual therapy as an approach to resolving interpersonal injuries. In E. L. Worthington, Jr. (Ed.), Handbook of Forgiveness (pp. 379-391). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Mullet, E., Girard, M. & Bakhshi, P. (2004). Conceptualizations of forgiveness. European Psychologist, 9, 78-86. [ Links ]

Mullet, E., Neto, F. & Rivière, S. (2005). Personality and its effects on resentment, revenge, and forgiveness and on self-forgiveness. In E. L. Worthington (Ed.), Handbook of Forgiveness (pp. 159-182). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Neto, F., Pinto, M. da C. & Mullet, E. (2007). Intergroup forgiveness: East Timorese and Angolan perspectives. Journal of Peace Research, 44, 711-729. [ Links ]

Romig, C. A. & Veenstra, G. (1998). Forgiveness and psychosocial development: Implications for clinical practice. Counseling and Values, 42, 185-199. [ Links ]

Sandage, S. J. & Williamson, I. (2005). Forgiveness in cultural context. In E. L. Worthington (Ed.), Handbook of Forgiveness (pp. 41-56). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Worthington, E. L. (2005, Ed.). Handbook of Forgiveness. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Worthington, E. L. & Sherer, M. (2004). Forgiveness is an emotion-focused coping strategy that can reduce health risks and promote health resilience. Psychology and Health, 19, 385-405. [ Links ]

Wuthnow, R. (2000). How religious groups promote forgiving: A national study. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 39, 125-139. [ Links ]