Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.10 no.2 Bogotá May/Aug. 2011

Type of sexual contact and precoital sexual experience in spanish adolescents*

Tipo de contacto sexual y experiencia sexual precoital en adolescentes españoles

MARÍA-PAZ BERMÚDEZ**

GUALDERMO BUELA-CASAL

INMACULADA TEVA***

*Acknowledgements. The study was supported by a grant of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (BSO2003-06208). This study was also supported by a research grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (AP-2004-1493) to Inmaculada Teva. Authors thank Dr. Francisco Gude Sampedro for his methodological and technical contributions and Dr. Margaret Stroebe and Dr. Wolfgang Stroebe for their helpful comments and corrections.

**Dirección postal: Facultad de Psicología, Universidad de Granada, 18011 Granada, España. Correos electrónicos: maripaz@ugr.es; gbuela@ugr.es

***Dirección postal: Dpto. Psicología Evolutiva y de la Educación, Facultad de Ciencias de la Educación (Aulario), Universidad de Granada. Campus de Cartuja s/n, 18011 Granada, España. Correo electrónico: inmate@ugr.es

Recibido: febrero 3 de 2010, Revisado: mayo 20 de 2010, Aceptado: junio 20 de 2010.

Para citar este artículo

Bermúdez, M. P., Buela-Casal, G. & Teva, I. (2011). Type of sexual contact and precoital sexual experience in spanish adolescents. Universitas Psychologica, 10 (2), 411-421.

Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine characteristics of precoital sexual behaviors and types of sexual contact in adolescent. A representative sample of 4,456 Spanish high school students participated. These participants were selected by means of a stratified random sampling procedure. They completed a questionnaire about their sexual behaviour. It is a cross-sectional survey study. Differences according to age and gender in characteristics of sexual behaviour before the onset of sexual intercourse were found. Compared to females, males started non penetrative sexual experiences earlier, had a higher number of sexual partners and a higher percentage of males reported having had casual sexual partner. This study not only adds to knowledge about sexual behaviour before the initiation of sexual intercourse among adolescents, it also highlights the importance of developing sexual prevention strategies for young adolescents.

Key words authors: Adolescents, Precoital Sexual Behaviour, Sexuality, Spain.

Key words plus: Adolescent Psychology, Behavioural Sciences, Sexual Behaviour, Psychological Effects, Sex Education.

Resumen

El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar algunas características de las conductas sexuales precoitales y el tipo de contacto sexual, en adolescentes españoles. Participó una muestra representativa de 4.456 estudiantes españoles de enseñanza secundaria obligatoria. Se administró un cuestionario sobre conducta sexual. Es un estudio transversal descriptivo de poblaciones, mediante encuestas con muestras probabilísticas. Los adolescentes fueron seleccionados mediante un muestreo aleatorio estratificado, en función del tipo de centro educativo y de la comunidad autónoma. En comparación con las mujeres, los varones comenzaron las experiencias sexuales sin penetración a una edad más temprana, tenían un mayor número de parejas y un mayor porcentaje de ellos manifestó tener parejas ocasionales. Este estudio no solo contribuye al conocimiento sobre la conducta sexual de los adolescentes antes del inicio de las relaciones sexuales con penetración, sino que en él se destaca la importancia de desarrollar estrategias de prevención sexual en los adolescentes.

Palabras clave autores: Adolescentes, conducta sexual precoital, sexualidad, España.

Palabras clave descriptores: Psicología del adolescente, ciencias del comportamiento, comportamiento sexual, efectos psicológicos, educación sexual.

Introduction

Adolescence is a period in life characterized by multiple physical and psychological changes. It is a time when adolescents start to have their first sexual contacts and experiment with possibilities such as alcohol and other drugs consumption (Bayley, 2003; Williams, Holmbeck & Greenley, 2002). In part because of such behaviors, this population has come to be considered a risk group for sexually transmitted diseases (STD), HIV infection and unintended pregnancies (Teal Pedlow & Carey, 2004).

Several researchers have noted that sexual contacts are starting at earlier ages (Ballester Arnal & Gil Llario, 2006; Callejas Pérez et al., 2005; Chirinos, Salazar & Brindis, 2000; Mekkers, Klein & Foyet, 2003). According to several studies, sexual experience is frequent among young adolescents. For example, Serrano, El-Astal, and Faro (2004) reported that 70% of adolescent women had sexual activity. In another recent study conducted in Spain, Navarro-Pertusa, Reig Ferrer, Barberá Heredia, and Ferrer Cascales (2006) found that the majority of their adolescent participants had some sexual experience (coital or not). Moreover, Ballester Arnal and Gil Llario (2006) indicated that 14% of their participants whose ages were between 11 and 12 years old already had some kind of sexual contact.

There are good reasons to argue the importance to investigating sexual behavior before the onset of sexual intercourse, not least because any program aimed at educating adolescents in healthy sexual behavior needs to be based on better understanding of the nature of sexual activity among young as well as older adolescents. A large body of research has focused on the assessment of sexual risk behavior in adolescents who have already had sexual intercourse, such as non condom use, number and type of sexual partner, etc. (González Lama, Calvo Fernández & Prats León, 2002; Hartell, 2005). However, although great advances have been made in understanding adolescents' coital sexual behavior, there is still a lack of research relating to sexual behaviors that precede the onset of sexual intercourse (L'Engle, Jackson & Brown, 2006). In the few studies that have looked at precoital sexual experiences, the aim has typically been to identify factors that trigger the start of sexual intercourse (L'Engle et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2006; Navarro-Pertusa et al., 2006; Schwartz, 1999; Upadhyay, Hindin & Gultiano, 2006). Investigating precoital activities more broadly would provide valuable additional information about sexual risk behavior for STD/HIV infection and unwanted pregnancies (Upadhyay et al., 2006). Furthermore, this kind of investigation should contribute toward the prevention of health risk behaviors among young adolescents, who are at an age when behaviors may not yet be firmly established (and thus they may be easier to change). Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess characteristics of precoital sexual behaviors and types of sexual contact in adolescents.

Method

Participants

The sample was composed of 4,456 Spanish adolescents who attended public and private high schools. Age ranged from 13 to 18 years old (M = 15.61; SD = 1.23). Participants were 47.3% male and 52.7% female.

Measure and variables

A specially-designed questionnaire was used in which questions regarding sociodemographics, precoital sexual behavior and type of sexual contact were included.

Sociodemographic variables

Sociodemographic variables included gender (male/female); age in years (grouped for analysis into the categories 13-14, 15-16, 17-18); religion (Catholic, Muslim, Evangelist, Protestant, Jewish, Mormon, none, other); practicing religion (yes, no, a little) and sexual orientation identification (heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual).

Behavioral variables

Type of sexual contact. Participants were asked "Have you ever had any kind of sexual contact (kisses, petting or penetration) with another person?". There were three response options: No, never; Yes, I have had sexual contact but always without penetration; Yes, I have had sexual contact involving penetration. Those adolescents who reported having had no sexual contact stopped filling out the questionnaire at this point.

Sexual experiences of participants in the nonpenetration sexual contact subgroup. The following questions were included: "How old were you when you had your first sexual contact without penetration?"; "How many people have you had sexual contact without penetration with?"; "What type of sexual partner did you have at your last sexual contact without penetration?" To this question, participants had two response options, steady (boyfriend/girlfriend) or casual partner (one-night stand). Finally, they were asked "Did you use drugs (alcohol, marihuana, cocaine, etc.) at your last sexual contact without penetration?" The response options were yes or no.

Sexual experiences (without penetration) in the penetration sexual contact subgroup. It was indicated in the questionnaire that the questions in this section about pre-coital sexual contact referred to the past, during the time when they had not yet had sexual intercourse experience. Specifically, the questions were as follows: "How old were you when you had your first sexual contact without penetration?"; "How many people have you had sexual contact without penetration with?"; "In general, what type of sexual partner did you have in your sexual contact without penetration?" The response options were steady partner (boyfriend/ girlfriend), casual partner (one-night stand). The last question was "In general, when you had sexual contact without penetration, did you use any kind of drug (alcohol, marihuana, cocaine, etc.)?" Response options were yes, no, sometimes.

Design

According to the classification system proposed by Montero and León (2007), this was a cross-sectional descriptive survey study. The norms developed by Ramos-Álvarez, Moreno-Fernández, Valdés-Conroy, and Catena (2008) were considered to prepare the manuscript.

Procedure

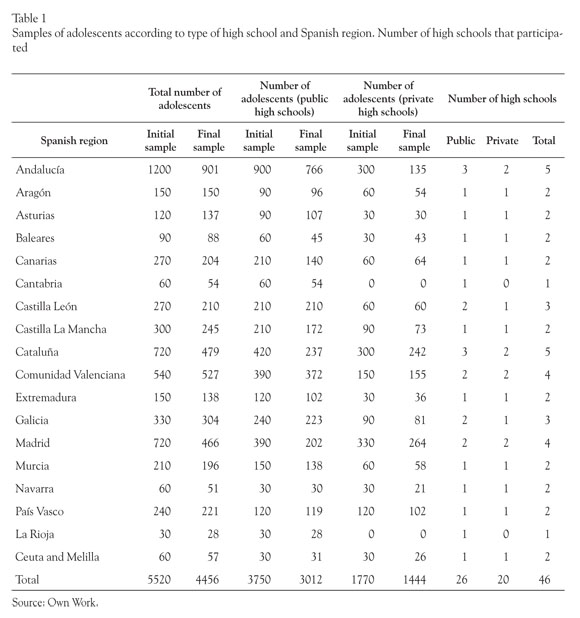

A stratified random sampling procedure was performed to select participants. The Spanish regions and the type of high school (public/private) were the variables that were considered in making the stratification. Sample size was set according to a maximum error of 1.5% and a 95.5% confidence interval. However, high school students were oversampled (1,000 more participants) taking into account possible excesses in dropout during data collection among this subgroup. For reasons of time and expenditure, the aim was to get the participation of one public and one private high school within each Spanish region. Only one public high school from Cantabria and one from La Rioja participated, due to 1) the low number of students to assess in these regions and 2) the fact that the majority of high school students of these regions attended public high schools. Likewise, the number of high schools was increased in those regions that had the highest number of high school students registered (Andalucía, Cataluña, Madrid, Comunidad Valenciana, Galicia and Castilla León). This increase was undertaken in consideration of the following aspects: 1) the proportion of public and private high school students registered in Spain and 2) the total number of selected public and private high schools as a proportion of the national total. High schools were chosen at random and a list with the Spanish high schools (Ministry of Education and Science, 2005) was used. Table 1 shows the initial and final sample of adolescents according to the Spanish region and the type of high school as well as the number of high schools that participated in the survey. The differences between the number of adolescents in the initial sample and in the final sample is due to dropouts, which -as noted above- were taken into account in the sample design.

Head teachers of high schools selected for inclusion in the study were contacted by mail and by phone. In cases where a head teacher refused to participate, another high school with the same characteristics was randomly chosen. Five researchers trained in questionnaire administration collected the data in the different geographical areas. Classes within high schools were randomly selected for participation. The same instructions and information about the study were given to all participants and anonymity and confidentiality were assured. Participation was voluntary; no student refused to participate. Consent forms were obtained and the Ethics Committee of the University of Granada (Spain) approved the study.

Statistical analysis

Two groups were considered: participants who reported having had only sexual contacts without penetration and participants who reported having had sexual intercourse. Chi-square and Student's t-tests were used. An analysis based on sampling design was performed. Analyses were conducted using STATA version 7.0 software. An alpha level of p < 0.05 was set for statistical significance.

Results

Demographic characteristics

More than one half of the participants were 1516 years old (54.4%). Of the remainder, 20.1% were 13-14 years and 25.5% were 17-18 years old. Concerning religion, nearly all of the adolescents (73.4%) reported being Catholic, 1.1% were Muslim, 0.6% were Evangelist, 0.3% were Protestant, 0.3% were Mormon, 21.8% indicated that they had no religion and 2.3% had some other religion. With respect to practicing their religion, 44.8% reported that they did not practice, 38.6% said they practiced their religion a little and 16.6% reported to practice their religion. With respect to sexual orientation, 95.4% reported being heterosexual, 2.5% were homosexual and 2.1% were bisexual.

Type of sexual contact

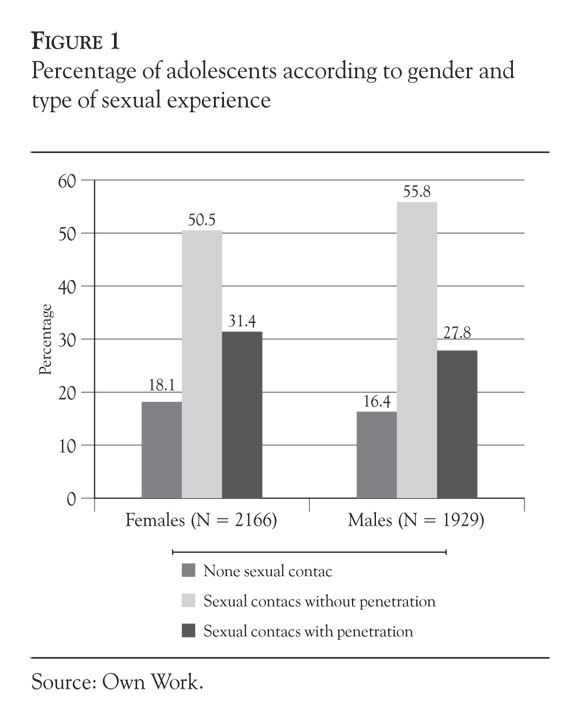

Regarding the type of sexual contact, there were significant differences between males and females (X2 (2) = 11.42; p = 0.003). Figure 1 shows males and females percentages according to the type of sexual contact. A higher percentage of females than males reported having had sexual intercourse (31.4% and 27.8%, respectively).

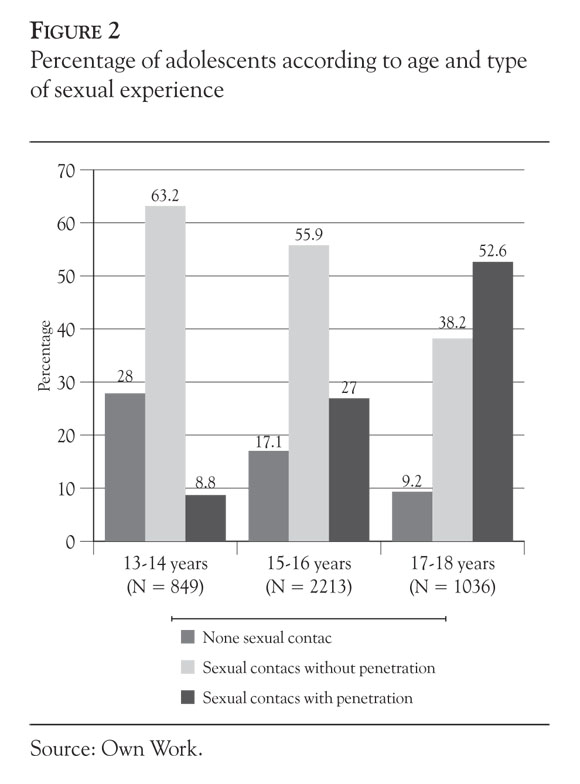

Significant differences in the type of sexual contact were found according to age (X2 (4) = 471.72; p = 0.000). Figure 2 shows the percentages of adolescents reporting different types of sexual contact according to the various age groups. Older adolescents (17-18 years) were the most sexually experienced (52.6% reported to have had sexual contacts with penetration).

Adolescents who had only had sexual contacts without penetration

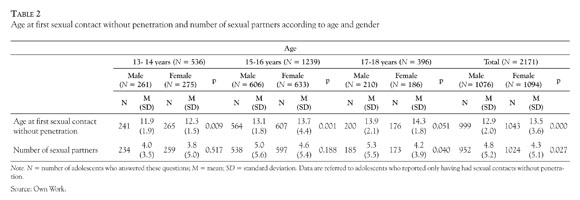

As Table 2 shows, males of all age groups started to have sexual contacts without penetration earlier than females. In total, average age of males at their first sexual contact without penetration was 12.9 years and in females it was 13.5 years (p = 0.000). Moreover, males of all age groups reported having had a higher number of sexual partners compared to females. However, there were only significant gender differences in the group of age of 17-18 years (p = 0.040). Males and females differed in the number of reported partners (M male= 4.8; M female= 4.3, p = 0.027)

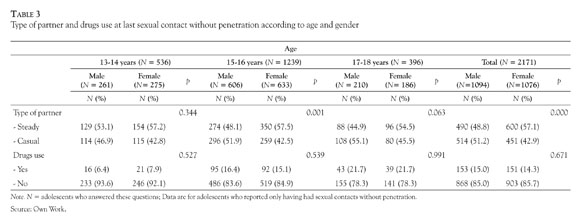

With respect to the type of partner and drugs use at last sexual contact without penetration, more males than females who were 15 to 16 years old reported having had a casual partner (51.9% of males compared to 42.5% of females; p = 0.001) (Table 3). In total, more females than males had a steady partner at the last sexual contact (57.1% of females and 48.8% of males). The majority of males had a casual partner (51.2%). The differences reached statistical significance (p = 0.000). Hardly any of the adolescents, neither males (85.0%) nor females (85.7%), used drugs.

Adolescents who had had sexual contacts involving penetration

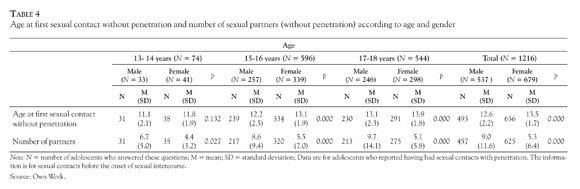

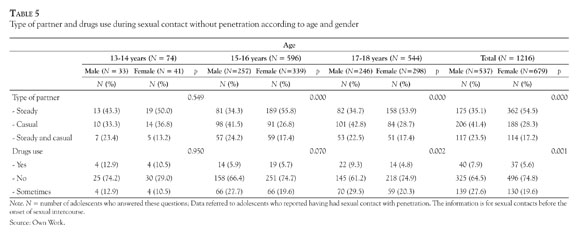

Results relating to age at first sexual contact without penetration and number of sexual partners are presented in Table 4. Males who were between 15 and 16 years old started sexual contact without penetration at an average age of 12.2 years compared to their females counterparts who began at an average age of13.1 years (p = 0.000). Likewise, males between 17 and 18 years old reported an average age at first sexual experience without penetration that was lower than females (M males = 13.1; M females = 13.9; p = 0.000). In total, males started sexual contacts without penetration at an average age of 12.6 years and females at 13.5 years (p = 0.000). Males reported a higher number of partners (M = 9.0) than females (M = 5.3) (p = 0.000). In general, older adolescents reported a higher number of sexual partners compared to younger (Table 4). The majority of females who were 15 to 16 years old indicated having had a steady partner when they had sex without penetration (55.8%) (Table 5). Nevertheless, the highest percentages of males of this age group reported having had sexual contacts without penetration with a casual partner (41.5%) or with concurrent steady and casual partners (24.2%). Similar percentages were obtained in the group of participants who were 17 to 18 years old and for the total sample. With regard to drugs use during sexual contacts without penetration, the majority of adolescents stated they did not use them (64.5% of males and 74.8% of females). It is noteworthy that 27.6% of males and 19.6% of females reported having used drugs sometimes when they had sex without penetration.

Discussion

In this study we have identified important differences according to age and gender of adolescents in patterns of precoital behavior and in the type of sexual contact they reported. Around 30% of students have sexual intercourse experience and this percentage is a little higher than other findings of recent surveys conducted in Spain. For example, Moreno, Muñoz, Pérez, and Sánchez (2004) found that 26% of adolescents between 11 and 18 years old had coital experience. Moreover, in the current study, the percentage of females with coital experience was higher (31.4%) than males (27.8%). These results contrast with Kotchick, Shaffer, Forehand, and Miller (2001) and Moreno et al. (2004) studies, which showed the proportion of adolescent males who reported that they had had sexual coital experience were higher than females. However, in line with other reports (Miller et al., 1997; Navarro-Pertusa et al., 2006; Palenzuela Sánchez, 2006; Ramos, Fuentes, Martínez & Hernández, 2003), we found that the majority of adolescents had sexual activity without involving penetration (50.5% of females and 55.8% of males). Therefore, sexual activity is obvious since early ages.

Regarding age, older adolescents report having had sexual contact with and without penetration more often than younger adolescents. Similar results have been found in other research conducted in Spain (Hidalgo, Garrido & Hernández, 2000). Serrano et al. (2004) found that adolescents had already sexual activity when they were 14 or 15 years old but we found that sexual activity can start even earlier. In general, male adolescents report an onset of sexual contacts without penetration at earlier ages than females, both among groups of adolescents who have coital experience and among those who only had sexual contacts without penetration. These findings are congruent with those of Upadhyay et al. (2006) who reported that male adolescents were more precocious than females in sexual activity without involving penetration. Likewise, Palenzuela Sánchez (2006) indicated that male adolescents began both sexual contacts without penetration and coital activity earlier than their female counterparts.

In line with other studies (Eaton, Fisher & Aaro, 2003; Lescano et al., 2006) in this study male adolescents were found to have more sexual partners than females. The majority of them reported having had sexual contacts without penetration with a casual partner. It is important to highlight that 27.6% of males and 19.6% of females with coital experience in the current study stated that they sometimes used drugs when they had sexual contacts without penetration. Given that alcohol and other drugs consumption have been found to be related to unprotected sexual intercourses and other risk behaviors (Baskin-Sommers & Sommers, 2006), prevention programs should also take this aspect into account: adolescents need to be alerted to the increased risks that such behavior is likely to involve and informed about the potential consequences of such behavior.

There have not so far been many studies related to sexual experiences before the onset of sexual intercourse (Schwartz, 1999; Upadhyay et al., 2006). The present study contributes to the literature through its assessment of important characteristics of sexual contacts among younger as well as older adolescents. Moreover, it provides information about Spanish adolescents' sexuality and their sexual history. Since a representative sample of high school students participated, generalization of findings to this Spanish population as a whole is possible. Furthermore, there are good reasons to extend this research to other countries: it would be important to examine the extent to which the patterns found in this culture can be replicated in other countries.

Turning to broader implications of the study: The finding that interpersonal sexual intercourse is so prevalent during very early adolescence needs to be taken into account in planning prevention of sexual risk behavior. An intervention strategy aimed at encouraging delay of the onset of sexual intercourse could help protect against HIV infection (Orji & Esimai, 2005; UNICEF, UNAIDS & WHO, 2002). Preventive strategies focused on this aspect are needed, and mainly in countries such as Spain, which has the highest HIV/AIDS prevalence index of Western Europe (Bermúdez & Teva-Álvarez, 2003; Bermúdez, Teva & Buela-Casal, 2004). To investigate sexual activity before the onset of sexual intercourse in adolescents provides an important information about teen/ agers sexuality. With this knowledge it should be possible to implement sexual education in school settings before risk behaviors appear. Likewise, it should be possible to take advantage of the time between precoital sexual activity and the beginning of penetrative sexual contact to educate adolescents in protective behaviors (Upadhyay et al., 2006), taking into account the differences between male and female adolescents. To do this, it would be advisable to undertake longitudinal studies to observe changes over time in sexual behavior and to establish causality relationships. Furthermore, other social factors (parental monitoring and communication, family composition, peers influence, community and teachers) associated with sexual behavior in adolescents (Aspy et al., 2007; Michael & Ben-Zur, 2007; Vukovic & Bjegovic, 2007; Wight, Williamson & Henderson, 2006) need to be examined in future research. Similarly, attitudes towards condom use in young people who have not coital experience (Widdice, Cornell, Lian & Halpern-Felsher, 2006) as well as adolescents' risk perceptions (Rodham, Brewer, Mistral & Stallard, 2006) and sexual sensation seeking (Gutiérrez-Martínez, Bermúdez, Teva & Buela-Casal, 2007; Spitalnick et al., 2007) need further investigation. All of there factors are major potential influences on future sexual behavior. The findings derived from such studies could then be included in HIV/STD prevention programs focused on young people.

References

Aspy, C. B., Vesely, S. K., Oman, R. F., Rodine, S., Marshall, L. & McLeroy, K. (2007). Parental communication and youth sexual behavior. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 449-466. [ Links ]

Ballester Arnal, R. & Gil Llario, M. D. (2006). La sexualidad en niños de 9 a 14 años. Psicothema, 18, 25-30. [ Links ]

Baskin-Sommers, A. & Sommers, I. (2006). The cooccurrence of substance use and high-risk behaviours. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 609-611. [ Links ]

Bayley, O. (2003). Improvement of sexual and reproductive health requires focusing on adolescents. The Lancet, 362, 830-831. [ Links ]

Bermúdez, M. P & Teva-Álvarez, I. (2003). Situación actual del VIH/SIDA en Europa: análisis de las diferencias entre países. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 3 (1), 89-106. [ Links ]

Bermúdez, M. P, Teva, I. & Buela-Casal, G. (2004). Situación actual del SIDA en España: análisis de las diferencias entre comunidades autónomas. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 4, 553-570. [ Links ]

Callejas Pérez, S., Fernández Martínez, B., Méndez Muñoz, P, León Martín, M. T., Fábrega Alarcón, C., Villarín Castro, A. et al. (2005). Intervención educativa para la prevención de embarazos no deseados y enfermedades de transmisión sexual en adolescentes de la ciudad de Toledo. Revista Española de Salud Pública, 79, 581-589. [ Links ]

Chirinos, J. L., Salazar, V. C. & Brindis, C. D. (2000). A profile of sexually active male adolescent high school student in Lima, Peru. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 16, 733-746. [ Links ]

Eaton, L., Flisher, A. J. & Aaro, L. E. (2003). Unsafe sexual behaviour in South African youth. Social Science and Medicine, 56, 149-165. [ Links ]

González Lama, J., Calvo Fernández, J. R. & Prats León, P (2002). Estudio epidemiológico de comportamientos de riesgo en adolescentes escolarizados de dos poblaciones semirrural y urbana. Atención Primaria, 30, 214-219. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez-Martínez, O., Bermúdez, M. P., Teva, I. & Buela-Casal, G. (2007). Sexual sensation seeking and worry about sexually transmitted diseases (STD) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among Spanish adolescents. Psicothema, 19, 661-666. [ Links ]

Hartell, C. G. (2005). HIV/AIDS in South Africa: A review of sexual behavior among adolescents. Adolescence, 40, 171-181. [ Links ]

Hidalgo, I., Garrido, G. & Hernández, M. (2000). Health status and risk behavior of adolescents in the north of Madrid, Spain. Journal of Adolescent Health, 27, 351-360. [ Links ]

Kotchick, B. A., Shaffer, A., Forehand, R. & Miller, K. S. (2001). Adolescent sexual risk behaviour: A multi-system perspective. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 493-519. [ Links ]

L'Engle, K. L., Jackson, C. & Brown, J. D. (2006). Early adolescents' cognitive susceptibility to initiate sexual intercourse. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 38, 97-105. [ Links ]

Lescano, C. M., Vázquez, E. A., Brown, L., Litvin, E. B., Pugatch, D. & Project SHIELD Study Group (2006). Condom use with "casual" and "main" partners: What's in a name? Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 443.e1-443.e7. [ Links ]

Liu, A., Kilmarx, P., Jenkins, R. A., Manopaiboon, C., Mock, P A., Jeeyapunt, S. et al. (2006). Sexual initiation, substance use and sexual behaviour and knowledge among vocational students in northern Thailand. International Family Planning Perspectives, 32, 126-135. [ Links ]

Mekkers, D., Klein, M. & Foyet, L. (2003). Patterns of HIV risk behavior and condom use among youth in Yaoundé and Douala, Cameroon. AIDS and Behavior, 7, 413-420. [ Links ]

Michael, K. & Ben-Zur, H. (2007). Risk-taking among adolescents: Associations with social and affective factors. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 17-31. [ Links ]

Miller, K. S., Clark, L. F., Wendell, D. A., Levin, M. L., Gray-Ray, P, Vélez, C.N. et al. (1997). Adolescent heterosexual experience: A new typology. Journal of Adolescent Health, 20, 179-186. [ Links ]

Ministry of Education and Science. (2005). Registro Estatal de Centros Docentes no Universitarios. Retrieved February 23, 2006, from http://centros.mec.es/centros/jsp/Entradajsp.jsp [ Links ]

Montero, I. & León, O. G. (2007). A guide for naming research studies in Psychology. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 7, 847-862. [ Links ]

Moreno, M. C., Muñoz, M. V., Pérez, P. J. & Sánchez, I. (2004). Los adolescentes españoles y su salud. Un análisis en chicos y chicas de 11 a 17 años. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. [ Links ]

Navarro-Pertusa, E., Reig-Ferrer, A., Barberá Heredia, E. & Ferrer Cascales, R. I. (2006). Grupo de iguales e iniciación sexual adolescente: diferencias de género. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 6, 79-96. [ Links ]

Orji, E. O. & Esimai, O. A. (2005). Sexual behaviour and contraceptive use among secondary school students in Ilesha South West Nigeria. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 25, 269-272. [ Links ]

Palenzuela Sánchez, A. (2006). Intereses, conducta sexual y comportamientos de riesgo para la salud sexual de escolares adolescentes participantes en un programa de educación sexual. Análisis y Modificación de Conducta, 32, 451-496. [ Links ]

Ramos, M., Fuentes, A., Martínez, J. L. & Hernández, A. (2003). Comportamientos y actitudes sexuales de los adolescentes de Castilla y León. Análisis y Modificación de Conducta, 29, 213-238. [ Links ]

Ramos-Álvarez, M. M., Moreno-Fernández, M., Valdés-Conroy, B. & Catena, A. (2008). Criteria of the peer review process for publication of experimental and quasi-experimental research in Psychology: A guide for creating research papers. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 8, 751-764. [ Links ]

Rodham, K., Brewer, H., Mistral, W. & Stallard, P (2006). Adolescents' perception of risk and challenge: A qualitative study. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 261-272. [ Links ]

Schwartz, I. M. (1999). Sexual activity prior to coital initiation: A comparison between males and females. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 28, 63-69. [ Links ]

Serrano, G., El-Astal, S. & Faro, F. (2004). La adolescencia en España, Palestina y Portugal: Análisis comparativo. Psicothema, 16, 468-475. [ Links ]

Spitalnick, J. S., DiClemente, R. J., Wingood, G. M., Crosby, R. A., Milhausen, R. R., Sales, J. M. et al. (2007). Brief report: Sexual sensation seeking and its relationship to risky sexual behaviour among African-American adolescent females. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 165-173. [ Links ]

Teal Pedlow, C. & Carey, M. P (2004). Developmentally appropriate sexual risk reduction interventions for adolescents: Rationale, review of interventions and recommendations for research and practice. Annals of Behavioural Medicine, 27, 172-184. [ Links ]

UNICEF, UNAIDS & WHO (2002). Los jóvenes y el VIH/SIDA. Una oportunidad en un momento crucial. Retrieved June 20, 2006, from http://www.unicef.org [ Links ]

Upadhyay, U. D., Hindin, M. J. & Gultiano, S. (2006). Before first sex: Gender differences in emotional relationships and physical behaviors among adolescents in the Philippines. International Family Planning Perspectives, 32, 110-119. [ Links ]

Vukovic, D. S. & Bjegovic, V. M. (2007). Brief report: Risky sexual behaviour of adolescents in Belgrade: Association with socioeconomic status and family structure. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 869-877. [ Links ]

Widdice, L. E., Cornell, J. L., Liang, W. & Halpern-Felsher, B. L. (2006). Having sex and condom use: Potential risks and benefits reported by young, sexually inexperienced adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 588-595. [ Links ]

Wight, D., Williamson, L. & Henderson, M. (2006). Parental influences on young people's sexual behaviour: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 473-494. [ Links ]

Williams, P. G., Holmbeck, G. N. & Greenley, R. N. (2002). Adolescent health psychology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 828-842. [ Links ]