Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.11 no.4 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2012

Juvenile Justice System in Italy: Researches and interventions

Sistema de Justicia Juvenil en Italia: investigaciones e intervenciones

Patrizia Meringolo *

University of Florence, Italy

* University of Florence, Italy. Departament of Psychology Via di San Salvi, 12 - Pad. 26 - 50135 Firenze. E-mail: patrizia.meringolo@unifi.it. ResearcherID: Meringolo, P. G-9292-2012.

Recibido: octubre 1 de 2011 | Revisado: mayo 10 de 2012 | Aceptado: agosto 10 de 2012

Para citar este artículo:

Meringolo, P. (2012). Juvenile justice system in Italy: Researches and interventions. Universitas Psychologica, 11(4), 1081-1092.

Abstract

This paper talks about the juvenile justice system in Italy. The author describes the interventions done with minors, boys and girls aged from 14 until 18 years, who have committed offenses of the civil or penal code, by the New Code of Criminal Procedure for Minors (1988). The Procedures have had some positive psychological aspects, aimed to avoid detention, thanks to alternative measures and strategies for inclusion, including also the minors living in the South, that are often involved in mafia-crimes. Nonetheless there are more negative psychological issues, because alternative punishments are not often applied to minors that lack social networks, particularly to foreign ones. Three examples of participatory researches will be shown, promoted by the Municipality of Florence, Department of Psychology and Third Sector Associations, aimed to promote psychological and social inclusion of minors (particularly those coming from abroad), with the commitment of active citizenship organizations, with an evaluation of their strengths and weaknesses.

Key words author: Juvenile Justice, Social Inclusion, Participatory Research, Local Community, Foreign minors.

Key words plus: Social Psychology, Social Inclusion, Italy.

Resumen

Este artículo describe el sistema de Justicia Juvenil de Italia. El autor describe las intervenciones realizadas con menores, jóvenes con edades entre los 14 y 18 años que habían cometido delitos previstos en el Código Civil o en el Penal, bajo el Nuevo Código de Procedimiento Criminal para Menores de 1988. Los procedimientos han tenido algunos aspectos psicológicamente positivos, dirigidos a evitar la detención, gracias a las medidas alternativas y estrategias para inclusión, incluyendo también los menores que viven en el sur, que con frecuencia se ven involucrados en crímenes de la mafia. Sin embargo, existen más temas negativos desde el punto de vista psicológico, debido a que usualmente los castigos alternativos no se aplican a los menores por falta de red social, especialmente a los extranjeros. Se presentan tres ejemplos de investigaciones emprendidas por la Municipalidad de Florencia, el Departamento de Psicología y las Asociaciones del Tercer Sector, dirigidas a promover la inclusión psicológica y social de menores (especialmente los extranjeros), con el compromiso de organizaciones civiles activas, con una evaluación de sus fortalezas y debilidades

Palabras clave autores: Justicia juvenil, inclusión social, investigación participativa, comunidad local, menores extranjeros.

Palabras clave descriptores: Psicología social, inclusión social, Italia.

SICI: 2011-2277(201212)11:4<1081:JJSIRI>2.0.CO;2-F

Theoretical background

Juvenile justice system in Italy has its roots in the wide theoretical debate about social rules and social opportunities developed in the Seventies, who leaded to important reforms in psychiatric health (Law 180/1978), and in penitentiary law (Law 354/1975.) In Italy, social problems have been seen as complex phenomena that emerge from the interactions between real needs, perceptions of those needs in the particular sociopolitical and cultural situation, and the definitions and choices of the agencies of social control (Pitch, 1985). In the Italian case, thus, there are many influential factors, related to the conflict and negotiations between the national and local levels of the State and governance, and to the specific relationship established in the Italian context between the state and the civil society; situation that may cause community's participation in crime control strategies (Selmini, 2005).

Also, a large body of investigations, has theories focused on punishment and penology, relations between criminal sciences and criminal policies, relations between psychiatry and criminal justice system, preventive policies and actions (Curi & Palombarini, 2002), social representation of deviance, criminal justice system for juvenile offenders (Pavarini & Melossi, 1977), also deepening social meanings of crime (De Leo & Patrizi, 1992), and importance of educational treatments (Guetta, 2010; Meringolo, 2010).

Italian juvenile justice system concerns boys and girls aged from 14 to 18 years, who have committed offenses of the civil or penal code (Sportello di Informazione Sociale Provincia di Torino, 2011). Note: It is impossible to charge criminally a person aged less than 14 year, it is possible though to charge the youth of ages from 14 to 18 years, noticing that the person isn't mentally ill, that have to be assessed case by case. For juvenile offenders life imprisonment cannot be sentenced, this by a rule from Italian Constitutional Court (Sentence n. 168/1994), that accomplished Art.31 of Italian Constitution foreseeing a special protection for childhood and youth. Sentences are served in juvenile justice institutions until 21 years, and cognizance of Juvenile Court remains until 25 year.

The New Code of Criminal Procedure for Minors (1988) has considerably reduced the number of minors in Criminal Institutions: from more than 7000 entries each year before 2000 until the present day. The main purpose if possible is to avoid detention and use alternatives measures (probation, community work, etc.), and strategies for inclusion in social life (Art. 1, and Art. 21 and 22.) As a protection of minors' psychological and educational development, institutions take care first of all the personality assessment (Art. 8 and 9), for a better planning of activities, try to prevent minors' labeling risks — both with a suitable treatment and avoiding spread of information about their deviant behavior (Art. 13, 14 and 15) — and pay attention to preserve minors' intimate networks, if existing and reliable, and to increase their formal and informal social networks.

Besides these important results, however, there are some negative issues that will be shown below, because recourse to juvenile imprisonment doesn't seem to decrease, especially for young people that lacks social support, or comes from abroad.

Juvenile Justice Procedures in Italy

Arrest: May be done both if in the act of the crime or under investigation, with some rules to protect minors during legal procedure, e.g. Information about taken measures, emotional and psychological support, presence of specialized professionals interacting with them, suitable pursuance of the law and privacy policy.

Preliminary Investigation: The Magistrate in charge for preliminary investigation decides if the minor may be released or leaded in a Community for juvenile offenders until judicial authority's decision. Minors on trivial charges may be leaded to a Community or even home.

Centers and communities for first reception: They shelter minors that aren't able to drive themselves or with their relatives back home. The centers haven't the feature of a prison (there aren't bars, even if there are guards), and their purpose is to detain minors up to four days. During their stay these children are observed by a specialized team (psychologist, educator, youth worker), that writes a first report for the Juvenile Judge. These centers may be also organized as small custodial communities with a "family" structure and a prevailing educational value. After the four days, the Judge decides the measure for the minor, founded on the following criteria: A non interruption of their educational process, reduction of harm caused by the proceeding, a quick judging process and detention as a residual choice.

Communities: There are public communities (depending on Juvenile Justice Administration, or private communities, associations or cooperatives working with adolescents), acknowledged by Regional Authority. This must follow requirements such as family organization, presence of other youngsters not in charge of justice, no more than ten people per group and employment of professional workers.

Detention: The minor is leaded in a Juvenile Prison (Istituto Penale Minorile, IPM). This measure is provided for offenses with punishments over 9 years and must be justified for risk of tampering with the evidences, or of running away, or repeating the offense.

In IPM there are minors submitted to a criminal measure, and also young adults who committed a crime when they were minors and — according to Italian law - may stay in juvenile prison until 21 years old. The IPMs through all Italy are sixteen in total, and are located in most of the Italians regions.

Alternative measures that can

be decided by the Judge

House arrest: The Court requires that the minor can stay at the family house, sometimes with moving limitations, and may allow the moving from home to school (or other educational related activities).

Probation: The Judge can adjourn the trial and start up procedures for probation, asking Social Services to plan an intervention, after which the minor will be assessed and —if the evaluations' result is positive— the offense can be discharged. The Social Services for Juvenile offenders cooperate in promoting, and protect youth rights with other services of Juvenile Justice and with Community Social Services.

Nonsuit judgment: During preliminary investigations the Judge, by request of Prosecuting Attorney, can decide nonsuit judgment if the offense is trivial and criminal behavior seems occasional.

Pardon for juvenile criminal offenders: It's a release decided by the Judge for a first-time juvenile criminal, related to an expected punishment less than 2 years.

Substitute measures: Instead of detention for punishment lower than 2 years, part-time detention, or conditional release may be applied.

Now the most common choice in alternative measures for criminal minor is probation in conditional release.

Data

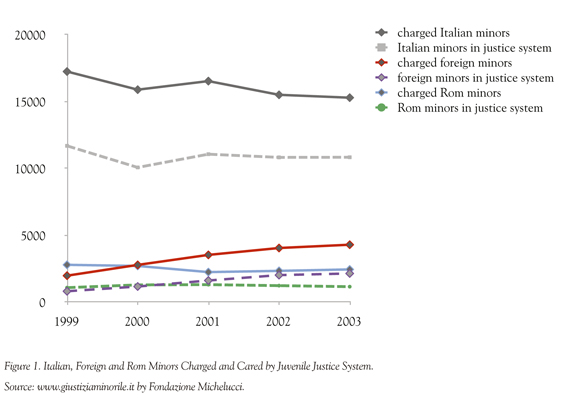

Significant investigations about juvenile justice intervention can be found in a research leaded by Fondazione Giovanni Michelucci di Firenze (Tosi Cambini, Albertini & Bianchi, 2005). Following graphics show minors in IPM and the trending in the last years.

Data source for all the following figures comes from Dipartimento della Giustizia Minorile (2011). Nevertheless the data has been revised by researchers of Fondazione Michelucci, to show best information of minors, and also to fill the gaps in collecting the data within juvenile institutions. We will present the situation concerning the years with an increasing number of juvenile offenses, and then the actual situation in juvenile prisons.

Figure 1 shows the different trending between the number of charged minors: We can see that often for Italian youngsters offence doesn't means an entry in the justice system, while for foreign minors, especially those belonging to Rom ethnic group, the percentage is higher.

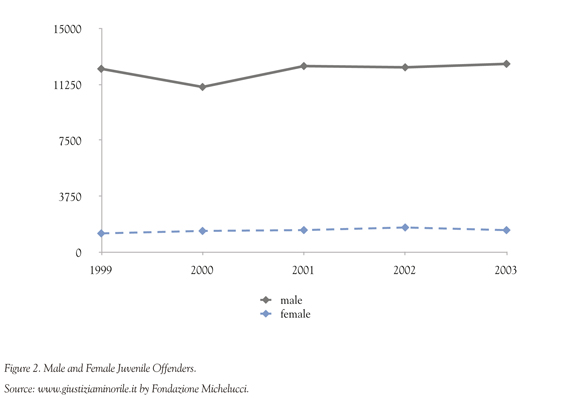

Figure 2 shows the great difference between males and females within juvenile offenders cared by the justice system.

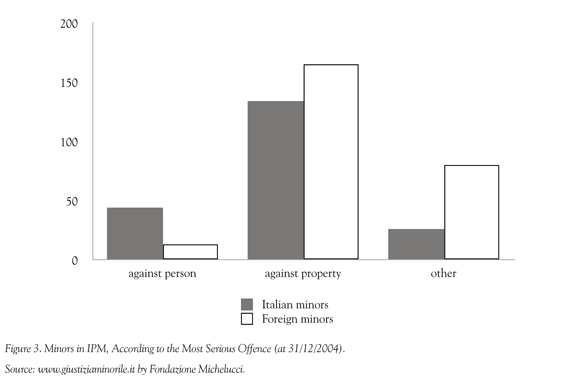

If we analyze the crimes where minors are involved (Figure 3), it can be observed that Italian minors are mostly charged with crimes against people (and this is because of their involvement in organized crime), while foreign minors are often charged with offence against property, crimes related to drug trafficking, or because violation of migration laws.

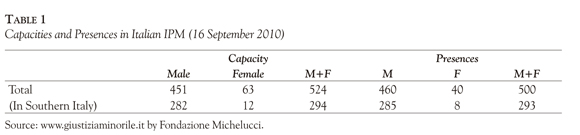

The following table (Table 1) is about the most recent data of capacity and presence in Italian institutions for minors. The total of presences is close to the capacities, even if the last aren't well distributed. The greatest presence of minors, particularly males, is in the southern IPM and in relation to mafia crimes, while the more crowded institutions are in the greater northern towns.

The number of crimes charged by minors in Italy is less than 40.000 per year. However the number of involved minors is surely lower, because some of them are charged several times. About 6.500 of them cannot be charged because they are not yet fourteen. The data is quite steady; perhaps it might be slightly decreasing. Among them, foreigners are 25% and less than 20% are female.

Half the crimes are against property, about 25% against individuals, and about 13% are crimes related to drug trafficking (Dipartimento della Giustizia Minorile, 2011).

The number of juvenile offenders in Italy is lower than European: 2.6% of committed crimes: 23.9 in the UK, 21% in France, 12.9 % in Germany and 5% in Spain (Maffei & Merzagora Betsos, 2007). Data is difficult to compare with other countries, because of the differences between law systems and the definitions of the children offenders' age.

As we have already said, entries in IPM are decreasing from about 1.900 at the beginning of 2000, to about 1.200 in 2009. Among them, female number was the one that decreased the most, and foreigner minors, who were prevalent in the past years, with a peak on 2004 with 60% of presences, are now 43%, thanks to local communities' policy about their social inclusion.

IPM in Italy are now 16 (on 2011), located in almost all regions. Four of them have girls' divisions. The majority of IPM are located in the South and in the Islands, because of the marginality and poverty of this places, and particularly of the minor's involvement in organized crime, as mafia (in Sicily), camorra (in Campania), and ndrangheta (in Calabria), who offers a sort of training in professional crimes. These organizations are widespread in many other regions, with the same — even though lower — effects for youth.

Foreigner minors in IPM are 65% in the North West of Italy, 71.2% in the North East, 70% in Central Italy, 15.5% in the South, and 11.9% in the Islands. Their number is higher in northern regions, because migration is headed towards more industrialized regions, as those in the north side of the country.

Minors' number in the present day is about 450-500. Is important to notice that this is their real number, because it's independent from the reentries. Within IPM young people aged from 18 to 21 years is about 40-45%, and even more. On 2009 they were 57%, and in the same year it increased until reaching 61% of presences. The longer stay of youngsters in institutions allows a better care of their educational, work or rehabilitation process, but it may cause some strained relationships among guests.

Employed staff in IPM on 2900 was composed by 1.390 units, both office-workers and youth workers, and 800 prison officers. Youth and social workers are nevertheless the minority, and often they work away from Institution: Their number also includes those involved in "criminal external area", like in local communities.

Some negative aspects

Juvenile detention, as we said before, doesn't seem decrease. Alternative punishments are not applied generally to minors lacking social networks to support them (family, school, job), particularly to those coming from abroad or Italian minors living in the South.

Boys and girls coming from abroad are often submitted to preventive detention. In such cases juvenile prison becomes a way to contain, and restrain their marginalization and poverty.

In the South of Italy there are many Italian youngsters with a final judgment who are shut down in prisons until they are 21 years when they are moved to adult imprisonment. For them juvenile justice doesn't foresee real recovery efforts, but rather stresses criminalization, preparing them for a future life marked by continuous entries to jail.

About foreign minors

Italy was the native country for many migrants in the last two centuries. In the Nineties, because of the Balkan's wars, the crisis in Eastern Europe, and poverty in the North of Africa, Italy became rapidly a host country for migrants, both adults and children. A large number of them had not a real plan for their migration, so if youngsters didn't found a study or work opportunity they most likely were about to become a deviant group in society.

In IPM foreign minors are a very heterogeneous group, including those who came for family reunification, or were born in the country of migrant parents, or arrived here alone, escaping from war and poverty. They are vulnerable in two ways (Abbiati, 2010): Being underage minors who aren't able to fulfill their need on their own, and because of the migration status that turns them to "stranger" and "other" to the eyes of the other citizens. What's more, those who are unaccompanied, without a legally responsible adult, are facing all alone the difficulties, mostly when their behavior is unsuitable and needs boundaries. Most of them can become deviant and undertake a criminal career. Sometimes they are unable to solve their migrant situation because they can't reach the proper information and know the legal procedures.

Forced to grow up quickly, they are often distrustful. It's quite difficult for them to have significant Italian adults, perceived sometimes as the reason of their detention. Cultural mediation appears as an indispensable means not only to translate procedures, but to really understand cultural needs. The most serious problems however appear outside, and at times foreigner minors may have more opportunities during their stay in IPM than after their release.

Psychosocial aspects

Presence of IPM in Italy

IPM, although sufficient, is not well distributed. Some of them are overcrowded, in unsuitable buildings, built originally like prisons and then readapted (Prina, 2010). Often there bigger rooms and the basic logic and the organization is oriented to guard and control, although this doesn't prevent violence. Other problem (important in financial crisis) is related to the great maintenance charges and relevant operating expenses. In conclusion: High costs and low functionality (Pazè, 2010).

Despite the low number of present minors, we can observe overcrowded situations o other emergencies and frequent transfers, with negative outcomes on the wants to achieve socialization with local community. The most serious problem concerns foreigner minors, who have fewer possibilities for planning their rehabilitation due to social and cultural barriers between them and institutions.

Reducing detention

By law reforming juvenile trial (1988) detention would be a "residual" treatment, and we can see that youth inmates are decreasing. "Less prison", doesn't produce more deviance. We know that is rather prison that may cause more criminality: Minors with higher stays "in" are authors of more serious and repeated crimes, are older than the other kids or are coming from abroad (and then with less inclusion possibilities). In IPM there aren't usually minors for whom it is possible to plan educational interventions. For the most of them their stay is short. For foreigners or Rom minors detention is often "justified" by social control. So it ends in a containment and stigmatization for marginalized individuals who frequently commit crimes as thefts (e.g. Rom youth), drug trafficking and so.

Age

IPM isn't always a "juvenile" prison, for relevant presence of young-adults (aged 18-21) carrying on their educational treatment. This may cause difficulties in relationships inside. There are different points of view in front of such phenomenon, with different evaluations on possible outcomes, and the question is still under discussion.

Employed professionals

Everyday management is mostly carried out by prison officers (whose number is the highest in EU), while educational staff is prevailingly employed outside. Even though they are more trained than in the past, the outcome is that IPM is focused more on custodial aims than in educational treatments. For facing relationship with minors from abroad and Rom, cultural mediators have been engaged. Such professionals are few and often are doing voluntary work.

Quality of treatment

Quality has been undoubtedly improved, paying attention to minors' needs and local communities support. Fewer numbers of minors and better professional training have leaded to more effective programs, at least for Italian minors. There are significant experiences in planning educational treatments that may continue after release, activities such sports or drama, cooperation with local communities, and also specific treatments for young sex offenders or for those in mafia related crimes.

Alternative punishments

Several authors (Pazè, 2010) underlined the importance of semi-detention, house arrest (everyday or in the weekend), conditional release, punishment based on restoring behavior, or on public services (as in other countries), to lessen even more the figure of detention.

The real difficult in creating an alternative punishment lies in the lack of social resources, particularly for minors with more needs: Migrants, minors coming from families with multiple problems, or gipsy minors. For all of them is almost impossible to grant custody to their families. The same goes for children involved in mafia or other organized crime, where their social network cannot be thought as a resource for rehabilitation.

Networking with Local Communities

and Local Authorities

Planning a community - based punishment networking between Justice and Social Services is important. Interventions may be moved in a "criminal external area", tied with existing or new resources in the local communities. Local authorities may play an important role, paying attention to juvenile offenders' needs, planning their future inclusion, reducing stigma against them and building (or rebuilding, if possible) social networks to increase opportunities for their effective rehabilitation.

The entry in judicial proceeding and release are the most critical moments, and becomes the most relevant to the psychologist's work: Entry time for planning treatment and before release for preparing an effective re-inclusion. Previous leaves, during detention can be important to help keep existing networks, build new relationships and learn social skills and a "legal" way of life.

Juvenile criminal mediation

The Law n. 448/1988 followed international experiences and anticipated international documents as United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989).

Mediation is part of a restoring model, and may activate victim and offender, and is aimed to settle conflicts and build up an agreement. It is a way for meeting people involved in crimes often coming from conflict relationships and lack of communication, where roles of victim and offender cannot be clearly defined. Mediation is encouraged in the treatment of minor offenders. In 1998, a pilot mediation project was launched in Milan. Following the relative success of this initiative, mediation offices were later established in other locations, as Turin, Trento, Rome, Catanzaro, and other towns.

Community's commitment is a discriminating factor in restorative models, because of the possibility of building a relationship beyond single interests or individual features (or even prejudices). Community has a critical role in all these procedures, in monitoring their outcomes and in mentoring involved individuals or groups. Community means, in this field, local community, community of interests and community of care (M.E.D.I.A.Re, 2004).

Researches and interventions

In Italy several important experiences have been carried out to support inclusion of juvenile offenders. Penal institution of Bologna has undertaken many projects aimed to a better socialization of youngsters coming from abroad, despite its overcrowding that produce frequent transfers of guests, particularly of those who doesn't have a relationship in the local communities, meaning in most cases unaccompanied foreign minors.

A qualitative research (Abbiati, 2010) shows the professionals opinions about difficulties and possibilities in their treatment. They refer to cultural mediation as the main instrument to support inclusion of young people lacking of emotional and social opportunities. They also point out the needs coming from services, even in an advanced region, where it would be necessary to improve networking, so to have a supportive community after going away from the penal structure.

Other researches and experiences came from Tuscany, and are characterized by a partnership among different institutions, as Public Bodies, Third Sectors and Universities.

Social networks for migrant minors

The first described research, promoted by Municipality of Florence and Justice Social Services, was carried out by the Department of Psychology of the University of Florence (Team Community Psychology), and its goal was to analyze social networks for minors sheltered in Communities for first reception. Scientific literature shows that an indicator of a suitable integration may be the perception of formal and informal networks of migrant adolescents, and particularly involvement in them of individuals belonging both to the native country and the host community (Liebkind & Jasinskaja Lahti, 2000; Sam, 2000).

Participants: Minors (35) and professional (10) were interviewed. All interviews had been audio taped, transcribed and analyzed by means of Atlas.ti.

Results

Minors (as we will see below) talk about their social networks in native countries, relationships with their abroad family, have a heavy normative power. Generally they are unable to support with a real migration project.

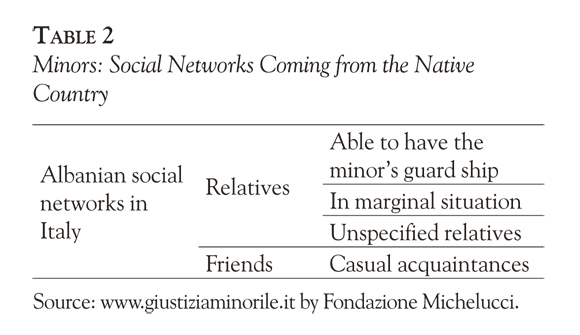

Social networks in Italy (Table 2) coming from native countries tend to be "dispersed", and often concern adults in marginalized situations. The core category appearing from the content analysis refers to relatives, some time able to care the minors: "my brother is here for seven years, regularly and with a job, with residence permit,... My other brother too is here for four years, with residence permit too...

They are working in the same place", other times in a real deviant situation: "my brother is living here. He is in prison, he was arrested because they found him with a thief, and they said that if you are with a thief you are a thief, too... Now he has been released [from jail]" or referred to unspecified relatives. Albanian friends, too, are often casual acquaintances, where the only common feature is their experience of migration.

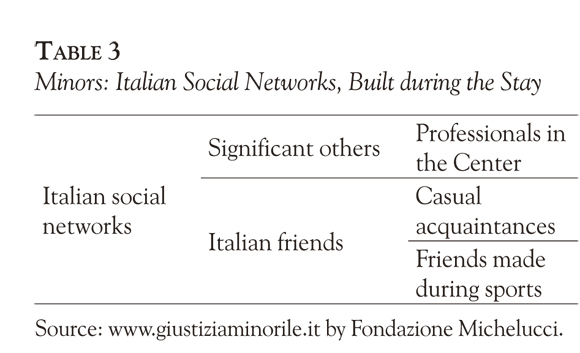

Building Italian social networks appears difficult for foreign minors (Table 3), Italian friends too are casual acquaintances: "I knew them at Michelangelo Square... I was with my brother, we went there for a walk...". Only someone who plays football talks about friends with who, perhaps friendship is perceived as mutual: "I have also Italian friends... Most of my friends are Italians, because I play football and so I have a lot of friends". The only significant adults seem to be professionals in the centers: "Social workers..., and then A. [the head of the center]...".

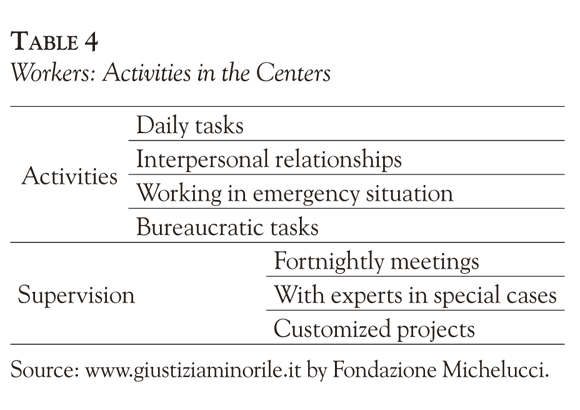

Social and Youth Workers (Table 4) describe their work as prevailingly focused on daily management and on emergencies: "Because of [they are] unaccompanied minors, or escaping, or set free by the police after abuse or exploitation...". However they have to face with heavy emotional and educational needs: "The outside world creates a lot of obstacles... we are trying to help them to face the problems...". Supervision appears as absolutely necessary: "... We discuss about our behavior... or when we meet with difficulties ... problems.".

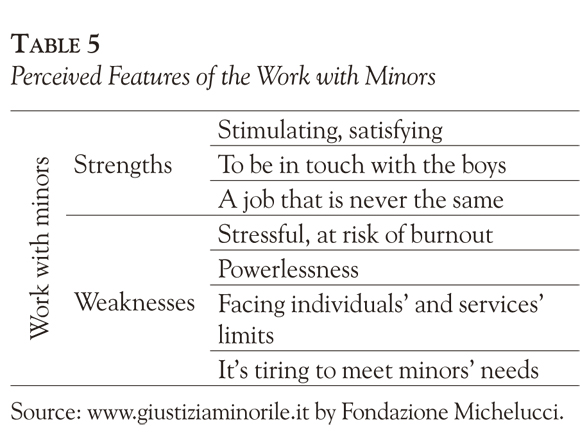

It is a arduous work, at risk of burnout (Table 5), often positively evaluated by them, as a stimulating experience: "When I am here ... It doesn't seem like work, the time flies", and "Is never the same". "and this is a strength, but also a weakness...", but often thought as stressful: "I would like to start a family... I think this isn't the work for me. in five years you can die." It is hard to do, and may lead to feelings of powerlessness: "Alone is not easy...", facing problems arising from persons or services: "We have a relevant turnover of minors . we are involved in first aid, and then projects are planned by others [educational communities for juvenile offenders]...", so many of them are thinking to this king of work as a temporary experience.

Youth workers' difficulties seem the other side of those expressed by minors: Both of them are living a stressful situation, where minors are asking, often unaware of emotional and not only material support, and the educators are aware and able to identify their needs, but emergency situations made them impossible to meet.

Progetto Ponte

The main characteristic of this project was the involvement of a Voluntary Association, working with elderly people and promoting social activities. Elderly supported minors in public utilities activities.

Theoretical background lays on awareness that punishment models, as well as inclusion strategies, rise from social constructions. For this reason it was important to work, with the involved social actors, on social meanings of minors' rehabilitation process, paying attention to inclusion strategies, aimed to prevent the minor's relapses into crime and to their rehabilitation.

Working on minors' powerlessness and internalized stigma, and at the same time on elderly people's stereotypes and prejudices, leaded to build empowering strategies for committed individuals and groups, and for the whole local communities.

The project was preceded by training the volunteers involved in this experience, and minors to reach better skills in planning their future, that literature points out as a protective element for reinclusion.

A particular attention was paid to mediation, underlining the role of local community, for avoiding that only single person or only Public Authorities, or Third Sector support inclusion process. But, above all, to the network and cooperation among all social actors.

Despite significant psychosocial results, particularly in attitudes towards juvenile offenders, the project had some weaknesses, first of all because the experience was greatly more effective for Italian than foreigner minors.

Progetto Fuori Twin Apple

and Progetto Icaro

The intention of these projects (each other created with a one year distance from the other) was to plan customized interventions1 in different times for a better inclusion of minors coming from IPM or Criminal Justice Services. Partnership consisted of IPM, Municipality of Florence, and Elderly Voluntary Association AUSER.

The core activity of this type of project was psychological activity, providing counseling in 3 different ways: a) Assessment of minor's motivation to work and meet individual features with opportunities for vocational training; b) Supporting motivation and work experience, providing help in difficulties and promoting better coping strategies; c) Evaluating with the youngsters the final experience.

There were 26 minors that came from multiple-problem situations and/or dysfunctional families. Most of them (70%) were foreigner, and already receiving help from social services. In several cases this kind of "revolving-door" among services seems to produce a negative effect in terms of low self-esteem and low self-efficacy, promoting negative identity.

Sometimes adults, parents or even teachers, may influenced the negative self-images increasing minors' powerlessness.

Some results: Strengths were the significant involvement of different kind of professionals, and a fine team work, with good communication and capability in facing problems and difficulties, in order to be able to cooperate no matter if they come from different professional experiences.

Weaknesses lied in a lack of relationships with those who had minors' custody, and also with the Social Services or Justice Services who were taking care them. This is an aspect that needs to be improved.

Besides a better external support and more enterprises willingness in offering job opportunities would be provided: Often it was impossible for minors to choose a suitable work for their features and competences.

A deeper evaluation of projects would need to be planned, not only for gathering information, but also to make an aware decision and progress, in order to optimize individual and social resources.

Promoting empowering strategies for deviant minors is certainly an arduous task for researchers, policy makers and local communities. However it should be try if society is willing to reduce juvenile crimes and punishments.

Notas al pie de página

1Done by V. Albertini and L. Rontini, supervised by Department of Psychology, Community Psychology Team.

References

Abbiati, F. (2010). Minori stranieri in istituto penale: la realtà bolognese. MinoriGiustizia, 67-72. [ Links ]

Curi, U. & G. Palombarini, G. (Eds.). (2002). Diritto penale mínimo. Roma: Donzelli Editore. [ Links ]

Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 22 settembre 1988 n. 448. Approvazione delle disposizioni sul processo penale a carico di imputati minorenni. Available at http://www.giustizia.it/cassazione/leggi/dpr448_88.html [ Links ]

Decreto Legislativo 28 luglio 1989 n. 272: Norme di attuazione, di coordinamento e transitorie del decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 22 settembre 1988, n. 448, recante disposizioni sul processo penale a carico di imputati minorenni. Available at http://www.giustizia.it/cassazione/leggi/dlgs272_89.html#TESTO [ Links ]

De Leo, G. & Patrizi, P. (1992). Laspiegazione del crimine. Bologna: Il Mulino. [ Links ]

Dipartimento della Giustizia Minorile. (2011). Retrieved on line on February 2011, from Dipartimento della Giustizia Minorile del Ministero della Giustizia http://www.giustiziaminorile.it/statistica/index.html. [ Links ]

Guetta, S. (Ed.). (2010). Saper educare in contesti di marginalità. Roma: Koiné [ Links ].

Liebkind, K. & Jasinskaja Lathi, I. (2000). Acculturation and psychological well-being among immigrant adolescents from different cultural backgrounds. Journal of Adolescent Research, 15(4), 446-469. [ Links ]

Maffei, S. & Merzagora Betsos, I. (2007). Crime and criminal policy in Italy. European Journal of Criminology, 4(4), 461-482. [ Links ]

M.E.D.I.A.Re. (2004). Atti del seminario conclusivo del progetto. Retrieved on line on February 2011, from http://www.provincia.torino.it/sportellosociale/minori/sm15 and http://www.giustizia.it [ Links ]

Meringolo, P. (2010). Interventi psicosociali sul carcere e sul reinserimento. In S. Guetta (a cura di), Saper educare in contesti di marginalità (pp. 57-65). Roma: Koiné [ Links ].

New Code of Criminal Procedure for Minors. (1988). Decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 22 settembre 1988 n. 448: Approvazione delle disposizioni sul processo penale a carico di imputati minorenni. Retrieved on line on February 2011, from http://www.giustizia.it/cassazione/leggi/dpr448_88.html [ Links ]

Pavarini, M. & Melossi, D. (1977). Carcere e fabbrica: alle origini del sistema penitenziario (XVI-XIX secolo) [The prison and the factory: Origins of the penitentiary system]. Bologna: il Mulino. [ Links ]

Pazè, P. (2010). Le pene per i minorenni. Un disegno di cambiamento nell'ordinamento penitenziario minorile [Editoriale]. MinoriGiustizia, 7-13. [ Links ]

Pitch, T. (1985). Critical criminology. The construction of social problems, and the question of rape. International Journal of the Socio logy of Law, 13(1), 35-46. [ Links ]

Prina, F. (2010). Che cosa è il carcere minorile oggi? MinoriGiustizia, 39-45. [ Links ]

Sam, D. L. (2000). Psychological adaptations with immigrant backgrounds. Journal of Social Psychology, 140(1), 5-25. [ Links ]

Selmini, R. (2005). Towards cittá sicure? Political action and institutional conflict in contemporary preventive and safety policies in Italy. Theoretical Criminology, 9(3), 307-323. [ Links ]

Sportello di Informazione Sociale Provincia di Torino. (2011). Retrieved on line on February 2011, from http://www.provincia.torino.it/sportellosociale/minori/sm15 [ Links ]

Tosi Cambini, S., Albertini, V. & Bianchi, M. (2005). Gli istituti penali per minorenni in Italia. Firenze: Fondazione Giovanni Michelucci. Retrieved on line on February 2011, from http://www.michelucci.it/pagine/allegati/IPM/Index.html [ Links ]