Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.11 no.4 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2012

Restorative Justice in Juvenile Courts in Brazil: A Brief Review of Porto Alegre and São Caetano Pilot Projects*

Justicia Restaurativa en Cortes Juveniles en Brasil: breve revisión de los proyectos piloto de Porto Alegre y São Caetano

Daniel Achutti **

Raffaella Pallamolla ***

Centro Universitario La Salle, Canoas, Brasil

* Report published, with few changes, in Conferencing: A Way Forward for Restorative Justice. Leuven, Belgium: European Forum for Restorative Justice, 2011. With many thanks to Estelle Zinsstag and Martin Wright for their support in reviewing the English version.

** PhD in Criminal Sciences (Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul — Brasil). Assistant Professor and Research Fellow at Centro Universitário La Salle (Canoas — Brasil). Criminal Lawyer. E-mail: dachutti@terra.com.br. ResearcherID: Achutti, D., G-9721-2012.

*** Centro Universitario La Salle, Canoas, Brasil. PhD student in Public Law at Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (España), and also PhD student in Sociology at Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (Brasil). Criminal Lawyer. E-mail: raffaellapp@terra.com.br. ResearcherID: Pallamolla, R. G-9721-2012.

Recibido: abril 20 de 2012 | Revisado: junio 10 de 2012 | Aceptado: agosto 10 de 2012

Para citar este artículo:

Achutti, D. & Pallamolla, R. (2012). Restorative Justice in Juvenile Courts in Brazil: A brief Review of Porto Alegre and São Caetano Pilot Projects. Universitas Psychologica, 11(4), 1093-1104.

Abstract

In this paper, it is presented the results of the first three years (2005-2007) of the application of Restorative Justice (RJ) in the Brazilian juvenile justice system. To this end, it was made a bibliographical and documental researches, so all data used in the paper has not been collected directly by the authors. Good results are verified, despite the almost complete absence of publicity given to the work developed in the country. It was also noticed a considerable lack of dialogue between those who are responsible for the programmes, the legal actors involved, and the local Universities. For even better results, it is suggested that all institutions involved improve the dialogue between them and encourage scientific researches of their own practices.

Key words authors: Restorative Justice, Restorative Practices, Juvenile Justice, Brazil.

Key words plus: Development Psychology, Social Behavior, Interdisciplinary Research.

Resumen

En este artículo se presentan los resultados de los tres primeros años (20052007) de la aplicación de la Justicia Restaurativa (RJ) en el sistema de justicia juvenil brasileño. Para ello, se realizaron investigaciones bibliográficas y documentales, por lo cual los datos utilizados en el estudio no fueron recogidos directamente por los autores. Los resultados verificados son positivos, a pesar de la ausencia casi total de publicidad que se dio a los trabajos desarrollados en el país. También se observó una considerable falta de diálogo entre los responsables de los programas, los actores jurídicos involucrados y las universidades locales. Para obtener mejores resultados, se sugiere la mejora del diálogo entre todas las instituciones involucradas y que se fomente la investigación científica de sus propias prácticas.

Palabras clave autores: Justicia restaurativa, prácticas restaurativas, justicia juvenil, Brasil.

Palabras clave descriptores: Psicología del desarrollo, comportamiento social, investigación interdisciplinar.

SICI: 2011-2277(201212)11:4<1093:RJJCIB>2.0.CO;2-M

Introduction

Restorative Justice in Brazil

Restorative Justice1 (RJ) has recently started emerging as an alternative approach to dealing with criminality2 in Brazil. This comes as a direct consequence of the lack of social legitimacy of the Brazilian criminal justice system and its incapacity and inefficiency to manage social conflicts. These reasons, added to the increasing social violence and a constant non-observance of civil rights by the State, require an intensive search for alternatives to the traditional criminal justice system3.

Currently, there is no legal support for RJ in Brazil, both in adult and juvenile courts. However, there is a draft law (No. 7006/2006) in the National Parliament, which plans to introduce RJ into the Penal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure, as well as in the Law of the Special Courts (law No. 9099/1995).

Despite the absence of a legal base, restorative justice is being applied since 2005 in some cities across Brazil. The first pilot projects began in Porto Alegre (Rio Grande do Sul State), São Caetano do Sul (São Paulo State), and Brasilia (Federal District), with funding from the Brazilian Ministry of Justice and its Secretariat for the Reform of the Judiciary, and also from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The project was originally called 'Promoting Restorative Practices in the Brazilian Justice System'4.

Currently, besides the aforementioned projects, there are many other programs dealing with restorative practices that have nevertheless not yet been researched and evaluated due first and foremost to their short existence. Most programs have been developed by Youth Courts, and a small part takes place in the Special Criminal Courts, which comprises the adult criminal justice system and are responsible for the judgment of minor offences only (crimes whose maximum prison penalty does not exceed two years).

Brasilia's programme adopted the Victim-Offender Mediation model in all of its applications, while São Caetano's and Porto Alegre's programmes have instead adopted the restorative circles model. We chose to briefly examine the latter two, since they offer some evaluations of their work and also a broadly view on the way conflicts are being dealt with inside the juvenile justice system, from a new perspective on the field. Brasilia's programme, although its importance will not be evaluated at this moment, since it follows the traditional way of conflicts administration.

The Project of São Caetano

do Sul - The First Three Years

The Project of São Caetano do Sul is developed within the Youth Justice System and focuses on young people accused of having committed a crime. As mentioned above, the project uses restorative circles, and the selection of cases (for the use of RJ) is usually made by the Youth Justice officials and the Public Prosecutors (specifically those who work in the section responsible for the Children and Youth Rights). In addition judges, social workers and other social actors can recommend the use of RJ in some cases.

The referral to circles usually occurs at the first hearing of the case, when the judge commonly imposes a socio-educational sanction on the young offender but in addition also suggests the use of RJ for the case5.

In the second half of 2006, the project was officially recognized by the Ministry of Education, which then decided to support it through the National Fund for the Development of Education (NFDE). The funds were sent to the Secretariat of Education of São Paulo State, to implement the project in two other cities in the same State: its capital, São Paulo, particularly in the region of Heliopolis6; and in the city of Guarulhos. In 2008, the project was also implemented in Campinas, another city located in São Paulo State.

The project called "Project Justice and Education: A Partnership for Citizenship", began as a pilot project in 2005 and received funding from the Secretariat for the Reform of the Judiciary, which is subordinated to the Ministry of Justice, and from UNDP. Such financing occurred until 2007, when the implementation stage of the project finished. At the end of 2007 and during 2008, the funding for the project was done by the Secretariat of Education of São Paulo State, through the Foundation for the Development of Education (FDE).

The project is developed in the Youth Court, under the supervision of Judge Eduardo Rezende de Melo and has the institutional support of the Court ofJustice — São Paulo State, and is addressed to youth authors of penal infractions.

According to Melo, Ednir, and Yazbek (2008), the project articulates a partnership between justice, education and community, in order to promote citizenship: Being a pilot project, the implementation of a restorative justice project is an effort to build a social democratic model of conflict resolution, stressed by strong community engagement. Guided by a quest for the promotion of active and civic responsibility of the communities and schools in which it operates, the project was based on a fundamental partnership between justice and education for the construction of spaces for conflict resolution and synergy of action in the school, community and forensics spheres. (p. 12)

We will now focus on the description of the first three years of the Project, the pattern of circles used in schools, community, courts, and finally the results obtained by the project in the period covered by the publication.

The First Year of Implementation:

Restorative Justice in Schools and in the Court

The first year of the project focused on the introduction of restorative justice in schools7 and with young offenders in conflict with criminal law. The project's goals were basically: (1) Allow the youth who had conflicts in schools to resolve them in this environment through restorative justice practices, thus avoiding the justice system; and (2) Enable the conflicts considered as criminal involving adolescents outside school environments to be approached through restorative circles at the Youth Court.

In the first stage of the project, educators from the three participating schools, parents, students, social workers and guardianship counsellors were trained by Dominic Barter8 to work with restorative circles — a restorative practice developed by the trainer himself based on Non-Violent Communication. According to O Cantano, Melo, Barter, and Ednir (2005 cited in Melo, Ednir, and Yazbek, 2008), this model can be defined as follows:

[it is] a space where stakeholders, supported by someone who knows the dynamics of the process (a conciliator9), get together in order to express themselves and to hear to each other, recognizing their choices and responsibilities and to achieve a concrete and relevant agreement related to the wrongdoing, that can involve all the involved persons. The dynamics of the circle are developed by three steps: Understanding each other, they start to perceive each other as similar, mourning and transformation. The choices and responsibilities related to the wrongdoing are recognized; agreement - the participants develop actions that repair, restore and reintegrate. (p. 13)

The Second Year: Restorative

Justice in the Community

In 2006, after reviewing the first year of the project, the organizers realized that in order to increase the use of RJ for youth involved in crime within their communities (outside the school environment) it is necessary to use restorative circles not only in schools and in the court, but also within the communities.

It was also perceived that sometimes there was a need to use another restorative practice, since circles are not appropriate for all crimes. Because of that, in 2006 a second pilot project took place, linked to the first one, which would be developed in the region of São Caetano do Sul known as Nova Gerty, which has the highest level of violence in the city. The second project, called "Restoring Justice in Family and Neighbourhood: Restorative and Communitarian Justice in Nova Gerty", became possible with volunteers who were trained to work with the Zwelethemba model, developed in South Africa. This model, as explained by the organizers, uses communitarian restorative circles and focuses less on individual needs than on building action plans to achieve changes in the community.

Initially, supported by a partnership between the Municipal Guard, the Military Police and the Family Health Program, the restorative circles used within the community dealt with neighbourhood and domestic conflicts. Subsequently, the circles began to be used in other types of conflicts: In neighbourhood disputes; among youths and their families; among young people themselves; and in municipal and private schools of the district (only state schools were involved in the first pilot, however municipal and private ones took part in the second one)10.

The Third Year: Development of Flows

and Intersections Between the Three Areas

(Schools, Community and Judiciary)

In 2007, the project aimed to develop standard procedures in the three areas of application (schools, community and judiciary) and to link them to one another to have a more systematic use of RJ.

At this moment, to make these intentions possible, the project started using the term "referrer" to designate the persons responsible for referring cases to one of the existing alternative methods of conflict resolution,11 and started training them specifically to exercise this function. The referrers were trained to explain to the parties the possible alternative ways to face the conflict, the implications of participating in a restorative procedure and their right to have legal assistance before their final decision. These explanations seek to ensure the voluntariness of the participation of everyone involved.

Persons (or agencies) trained to refer cases to a restorative procedure were: Judges, public prosecutors, school principals, social workers (only those who work at the Youth Court), police agents, community health workers, guardianship counsellors, lawyers, and support groups for minorities and for drug addiction and alcoholism treatment.

As regards conflicts in schools and in the community, when the act has not yet been officially recorded in the criminal justice system (or is not reported), besides the possibilities aforementioned, it is also possible for parties themselves to seek a justice facilitator in the school or the community, depending on where the event took place. When one of the parties looks for the service, the other party is invited to participate in a pre-circle (the invitation is made by the party him- or herself, and the facilitator might help with the contact). Once both parties have taken their decision, the pre-circle is done separately, and at that moment it is checked whether there are people within their communities of care that might participate in the procedure.

Each restorative procedure contains three stages: First of all, the pre-circle stage, in which the restorative procedure is requested by one or all the involved parties, the offender and the victim are individually interviewed by the justice facilitator and both indicate people from their local communities whom they wish to include in the circle. All of them receive information regarding the procedure (principles, goals and role of each person).

Secondly, the restorative circle stage, in which all involved participate and try to reach an agreement; and the last one, the post-circle stage, in which the satisfaction of the victim and the offender is examined and whether the agreement was accomplished.

The restorative procedure observes the principles of voluntariness, horizontality and empathic communication, and a judicial review of the agreements is always possible when the parties ask for it.

The Process in Schools, in the

Community and in the Court

Each area of the project has a different procedure, so we will now examine separately the main features of each one of them:

Restorative circles in schools: The circles were performed only in State schools, which were trained to implement the project and deal with conflicts involving students, educators, families of the students and school staff. Theoretically, there is no limitation on the type of conflict that may be referred to a restorative circle.

If there is a conflict in the school environment, one of the involved persons or a third party may contact the school board, which then evaluates, together with the persons involved, if the case can be referred to a restorative circle. Another possibility is that one of the involved persons contacts the justice facilitator of the school directly. In both cases, all of them are informed about the possibilities to resolve the conflict, one of which is the restorative way. At this moment, those involved in the conflict have the right to legal assistance. Being aware of all alternatives to resolve the conflict, when it is possible to use the circle and if the parties agree to use it, then the circle is made with two justice facilitators, the persons directly involved in the conflict and their communities of care. If an agreement is achieved, after some time a post-circle is performed to check if it was adequate to the case, and whether the agreement was accomplished. If everyone is satisfied with the outcome and the agreement has been met, the case is closed and no disciplinary sanction is applied.

If the agreement is not accomplished, it is possible to make a new circle to try to reach a new one. If the involved parties refuse to make a new circle, the case can be resolved by the school principal or by the school board (which might apply an disciplinary sanction, in accordance with the school regulations), or referred to the police when the act is legally considered a crime.

Restorative circles in the community: The circles are held in communal spaces, especially in schools, because they are considered neutral spaces. The main goals are neighbourhood conflicts, violence in the family and among young people, and also other types of conflicts involving any community members.

If there is a conflict inside the community, one or all the persons directly involved can seek a justice facilitator of the district, who will explain the available alternatives to resolve the conflict, including the restorative way. Before any decision, the parties have the right to legal assistance. If the parties agree to participate in a restorative circle, then the justice facilitator invites their communities of care to inform them about the restorative procedure.

The circle then is performed with two justice facilitators, those directly involved in the conflict and their communities of care. An action plan is made and if all agree with it, after the circle a post-circle is performed, to check if the plan was appropriate and sufficient and whether it was accomplished. If the plan was accomplished and everyone is pleased with its outcomes, the conflict is considered resolved.

If the case has been referred by the Youth Court, the justice facilitator informs the judge about the results of the circle. At this moment, the public prosecutor and the attorneys must also express their opinions about the results. If the agreement respected the fundamental rights of dignity, respect and freedom, the judge approves it and the judicial proceeding is closed.

If the agreement is not accomplished, it is possible to make a new circle to try to reach a new one. If the involved parties do not wish a new circle and the case has been referred by the youth court, the case returns to the court, where the judge should follow the legal steps and continue the proceedings.

Restorative circles in the court: The circles are performed inside the court building and are used in three types of cases: (1) In cases where the Special Criminal Court is responsible for the judgment; (2) In some cases judged by the Domestic Violence Court (only those where the prosecution is conditional upon the wish of the victims12 - basically threats); (3) And cases from the juvenile justice, which are more numerous (the crimes committed by minors over 12 and under 18 years old).

When the circle takes place in the court the principles of voluntariness (informed consent), confidentiality and horizontality are respected, and those involved can have the assistance of a lawyer, both during the hearing and the circle, if they so desire.

When a case is referred to a justice facilitator by some of the referrers mentioned above, the facilitator informs the persons involved about the alternative ways to resolve the conflict, including the restorative circle. At this moment, the person involved has the right to legal assistance. If he or she wishes to participate in a restorative circle, the other involved party is sought and the same information in relation to the possibilities of conflict resolution is given to him. The other party also has access to legal assistance. Then, if both parties agree to participate in the circle, the facilitator invites their communities of care, to inform them about the restorative procedure.

Following from that, the circle convenes with two facilitators, those directly involved in the conflict and their communities of care. An action plan is discussed and agreed to. After the circle, a post circle is organised in order to check if the plan was appropriate and sufficient and whether it was successfully fulfilled.

If the agreement was accomplished and everyone is pleased with the outcome, the facilitator communicates the result of the circle to the court. When the case was provided by the Special Criminal Court or by the Domestic Violence Court (both in adult justice), the agreement is analyzed by the public prosecutor and the attorney. After it, if the agreement respected the fundamental rights of dignity, respect and freedom, the judge approves it and if the agreement is accomplished, the criminal procedure is closed.

On the other hand, if the Youth Court had referred the case, when there is an agreement, after the statement by the public prosecutor and the attorneys, the judge closes the process.

If the agreement is not accomplished and if it was not a deliberate act, it is possible to make a new circle to try to reach a new one. When the breach of the agreement is deliberate, the offender may still be prosecuted in the criminal or civil sphere, depending on the case.

If those involved do not wish to make a new circle, the negative result (lack of agreement) is communicated to the judge who should follow the legal steps and continue the proceedings.

Available Results after Three Years

of the Project Implementation

The project began to use restorative circles in three state schools in May 2005, and in 2006 all state schools have joined the project. However, not all schools performed circles in this period. In July 2006, the project also started to operate in the community.

Since its beginning until December 2007 (when the report about the structure, the goals and the outcomes of the project was done), 260 restorative circles were performed in schools, in the community and in the Youth Court. Of this total, 231 (88.84%) of them reached an agreement, and on the total of agreements, 223 were accomplished (96.54%).

As regards, the participants, 1022 people took part in the 260 circles (facilitators not included). Of this total, 510 people were directly involved in the conflict and 512 were from the community.

Only 39 circles were performed in the youth court, regarding minors who had committed a criminal act. Of this total, 37 reached an agreement, and in 34 of these the agreement was accomplished. In those 39 circles, 130 persons had participated. Among the persons, 59 were directly involved in the conflict and 71 were from the community.

The most common types of conflict in restorative circles performed in the youth court were assault/bodily injury (15), threat (7), disorderly behaviour (6), robbery (4), theft (3), illegal constraint (2), breach of the of peace (1), and damage to property (1) (sometimes, more than one offence may be present in one circle).

In the schools, 160 circles were performed. Of this total of circles, in 153 there was an agreement and all of them were accomplished. In those 160 circles, 647 persons participated. Among them, 317 were directly involved in the conflict and 330 belonged to the community.

The most common crimes were: Physical aggression (53), disorderly behaviour (46), disagreement (38), illegal constraint (25), threat (24), bullying (13), theft (4), breach of the peace (3), brawl (1), and others (1).

Finally, in the community, 61 circles were performed. Among this total, there was agreement in 41 cases, of which 38 were accomplished. 245 persons participated in the circles, and of these, 134 were directly involved in the conflict and 111 were from the community.

The Porto Alegre Programme

The Porto Alegre Programme is also developed inside the youth justice system, and is considered, since last year (2010) not anymore as a project, but as an officially recognized programme of restorative practices. It takes place in a specific place inside the Central Court building in the city, with designed officials to work on it, and is now known as Restorative Practices Centre (RPC). As mentioned before, this program also uses restorative circles as a RJ practice.

RPC is part of the Projeto Justiça para o Século 21 ("Justice for the 21st Century Project"), and its goal is, according to its coordinator Leoberto Brancher (2008) "to introduce restorative justice practices into the resolution of violent conflicts involving children and youth in Porto Alegre" (p. 11).

This project is used in two ways: (1) As an alternative in the prevention and solution of school and community conflicts. When the conflict is solved before its arrival in the justice system (with its multiple tentacles), and the parties are satisfied with the solution, it is con

sidered closed and people often do not take the issue to any part of the justice system (police, public prosecutor, judge, etc.); and (2) As a complementary function to the criminal justice system. In this case, restorative practices are possible at two points, according to research developed by the Centre for Research in Ethics and Human Rights (CREHR), from the Faculty of Social Work of Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS)13:

a) Firstly, as soon as the case enters the criminal justice system, a preliminary judicial hearing is held through a partner project called Projeto Justiça Instantânea (Instantaneous Justice Project — from now on, PJI). At this moment, the youth offender is sent to the RPC. In the majority of cases, it occurs before any indication of the penalty that eventually will be applied to the youth accused young person. If the use of restorative practice is considered enough to solve the conflict, the penalty is considered no longer necessary. But, if the judge and the public prosecutor consider that it is not enough, restorative practice will be used as a complement to the traditional system, during the procedure.

b) Secondly, during the execution of the penalty. At this moment, the official institutions that must execute the penalty get together and create a plan for the offender. The offender will have to stay for a period in a custodial institution and will also take part in restorative circles, if he agrees.

The main distinction between the aforementioned programs is that the Porto Alegre one also uses RJ during the execution of the sentence. According to the coordinators of the programme, the intention is to improve the content of the sentence by assigning new ethical meanings to it, following RJ principles. Although they know this is not the best moment to apply RJ in a specific case, this was the only moment they could use the restorative practices in the beginning of the programme, due to a considerable resistance from some legal personnel.

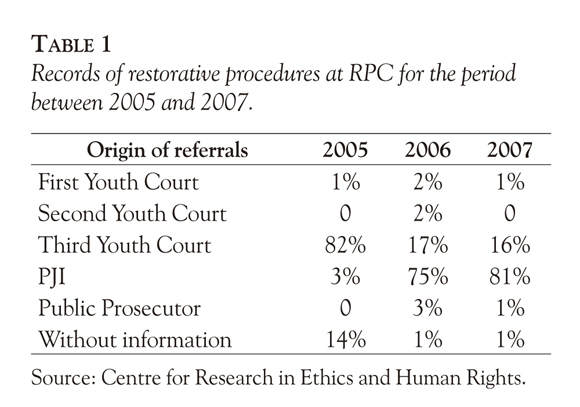

According to the aforementioned research, in relation to the origin of the processes that arrived to the RPC between 2005 and 2007, the percentage is as follows:

It can be observed, therefore, that there is a growing trend to refer cases to the CPR at the out-set, right after the entry of the case in the juvenile justice system. However, there are no published data on the number of cases in which a socio-edu-cational measure was not necessary due to a positive outcome of the restorative circle. This hampers the analysis on the use of restorative justice as an effective alternative to the traditional process or socio-educational measures derived from it.

The survey also reveals that the types of penal infractions approached by restorative circles in the same period (2005-2007) are quite varied, covering major and minor crimes, such as theft, robbery, body injury, threat, property damage and others, with even some cases of murder (11 during the three years). Cases from the city of Porto Alegre are given priority and those involving sexual or familiar violence are not attended. The total number of referred cases in three years is 380, including pre-circle (preparation of the meeting), circle (holding the meeting, which involves three steps: understanding, self-responsibility and compromise), and post-circle (monitoring compliance with the agreement) (To-deschini et al., 2008). From the total, 73 cases had a complete procedure (all stages observed).

According to the coordinator of the CPR, Tânia Benedetto Todeschini, and other restorative procedures coordinators, the CPR restorative procedures comply with the following principles: Voluntary participation; horizontality; admission by the offender about responsibility for the criminal act; focus on the offence not the offender (Todeschiniet al., 2008, p. 139).

After the case arrives at the CPR, its facilitators consider the possibility of use of a restorative circle, and it is used only with the free consent of the parties (adolescents and their care takers must agree, as well as the victim). In 2007, of the project started to use family circles in which the victim does not participate. As Aguinsky et al. (2008) explain, these are:

[...] Situations in which adolescents and those responsible for them express their willingness to participate even without the victims. They have the option using family circles, in which the adolescent offender, family members, significant others and community representatives and/or social workers get together for a dialogue to address possibilities for accountability and support related to social, familiar and communal relationships of the adolescents. (p. 33)

With regard to the contents of the agreements, it was found that they are most often related to symbolic than material issues. There was also commonly self-accountability from the young offender through an apology, accountability and involvement of parents and relatives, and community representatives in repairing the damage. The bonds within the family of the offender were strengthened, the needs of the offender, victims and their families were respected, and workers from the social assistance network participated. It was found that in 90% of all cases the agreements were fulfilled.

Regarding the satisfaction of the stakeholders, 95% of the victims were satisfied with the procedure and said they felt a greater accountability from the offender, once they could talk about the way they were affected by the damage and could better understand the facts surrounding the offence. It also made possible for them to not to look at the offender as a stranger anymore, but as a person. Likewise, 90% of the young offenders approved of the experience, mentioning that they felt treated with more respect and fairness. Moreover, both victims and offenders understood the opportunity as a positive way to narrate and explain the damage caused by the act and the reasons for committing it.

Finally, the study examined the recidivism rate of young offenders who participated in the programme. It considered young offenders who re-entered the criminal justice system after they had participated in any restorative procedure, more than 12 months after their participation. The control group was made randomly of teenagers who had their cases sent to CPR, but did not took part in any restorative procedure and remained only in the pre-circle.

Of the total number of recidivists during the study period (2005 and 2006 cases, analyzed in 2007), 80% had not attended any restorative process or only attended a pre-circle. Among those who completed the restorative process, only 23% re-entered the system. Compared to the control group, adolescents who participated on the whole restorative procedure had a 44% percentage of re-offending, while the control group percentage was 56%. Thus, the research concluded that the results are positive and are consistent with the results of international experiences involving children in conflict with the law.

Regarding the use of a restorative procedure during the period of the socio-educational sanction, the survey was done separately, because of the special nature of the programme. As mentioned before, the programme is carried out together by FASE and FASC, and since 2005 both institutions train its employers to facilitate or mediate restorative meetings (circles).

In 2005 and 2006, cases referred to restorative circles at FASE were those which had a positive report regarding the possibility of progression14 in the execution of the sentence (from more severe to less severe conditions), and also those specially selected by the specialist staff of the institution, 139 cases were referred to restorative circles.

The participants in the circles were the adolescents, their families and significant others (girlfriend/partner, employer, friends), professionals, social workers, directors and workers of FASE. The victim does not participate15. The adolescents who attended the circles have been convicted, in most cases, for robbery (95 cases), theft (11), homicide (10), drug trafficking (7), and robbery with murder (6), among others.

Of the total, 92.7% of the cases ended with agreements, 75.6% of which were successfully observed by the parties. Agreements contained "the parties' acceptance of responsibility for support actions regarding health treatments, psychotherapy, inclusion in the labour market (mainly in the informal market), alternative housing for the post-institutional accommodation, and sporting activities" (Aguinsky et al., 2008, p. 43).

Regarding recidivism, the research is now under development, but already provides data on young people who attended circles at FASE between 2005 and 2006: Among a total of 128 youths who attended a restorative procedure, 21% relapsed (27 adolescents). In other words, 79% did not relapsed.

It is important to mention that, from 2007 on, the design of FASE and FASC projects has changed, and the restorative circles began to occur when the teenager at FASE has the possibility of sanction progress, which can be: Probation, community service or discharge from the sanction. Since the changes on the project, only 18 circles took place. However, FASE still perform restorative procedures with adolescents serving custodial sentences (Aguinsky et al., 2008).

Related to the stakeholder satisfaction (adolescents and their families) in these procedures (during the period of the socio-educational sanction), the percentage found is 80%. As a way to demonstrate the factors that could have lead to this result, researchers from the College of Social Work at PU-CRS related the following:

The possibility of adolescents to be heard, understood and valued in their needs was appreciated by them and also by their family members. The expressions of dissatisfaction are associated with unease due to exposure in a large group of issues that previously remained in the private sphere only; in addition there was frustration of some expectations of adolescents and their families regarding the reduction of sentence of imprisonment and social welfare support to help with specific material needs. (Aguinsky et al., 2008, p. 47)

Based on the available data, there are two main problems for this programme: First, the timing when restorative practices are being used (which is along with the socio-educational sanction), and, secondly, its probable inability to replace the traditional process or prevent the implementation of socio-educational sanctions, since at least for now, there is no data available about cases that were resolved only with restorative justice and therefore no clear example of its potential.

Conclusion

Despite the lack of legal base, RJ is being well developed in Brazil, and its results are encouraging. Considering the place where the programmes are being developed (inside the Judiciary Power), and the good results of the first three years, it is reasonable to conclude that it tends to collaborate with future plans in the country involving the use of restorative practices.

However, there are only few publications on the topic in Portuguese, and many lawyers, judges, public prosecutors and other legal or non-legal actors are still reluctant to discuss its possibilities further. This can be attributed more to ignorance than to disagreement related to RJ methods and practices, and for this reason maybe this scenario might change.

Both programmes (Porto Alegre and São Caetano do Sul) are promising, but rather than discuss it, now it is time to improve their mechanisms, increase their use and develop deeper researches about it. To encourage scientific researches and evaluations of both programmes is a good way of improving results and comprehending internal and external problems that might be avoided in the future.

As mentioned before, there is a draft law in the national parliament to modify the Penal Code and the Criminal Procedure Code and officially insert RJ into the criminal justice system. However, changing the law might not be a good idea at this moment, since the use of RJ is still recent and more discussions about it are needed before its institutionalization.

Notas al pie de página

1Despite the considerable difficulties on the definition of restorative justice, there is a relative consensus on the concept proposed by Tony Marshall (see, for example, Braithwaite, 2002; Strang, 2002; Shapland et al., 2006; Walgrave, 2008; Pallamolla, 2009; Hoyle, 2010; Ruggiero, 2011; etc.), for whom restorative justice can be defined as "a process whereby all the parties with a stake in a particular offence come together to resolve collectively how to deal with the aftermath of the offence and its implications for the future" (Marshall, 1996, p. 37.) For critical considerations on this definition, see Braithwaite (2002) and Walgrave (2008).

2For the words 'criminality' and 'crime' in Portuguese, we also use 'conflict', therefore all three words will be used interchangeably in this section.

3For critical visions on the Brazilian criminal justice system and the necessity on the search for alternatives for conflicts administration, see Bitencourt (1993), Azevedo (2000), Wunderlich e Carvalho (2002, 2005), Andrade (2003), Azevedo and Carvalho (2006), Carvalho (2008), Achutti (2009), Pallamolla (2009).

4 The names of the schemes are translated from the Portuguese by the authors of the section.

5It is necessary to mention at this point that the following description of the Project of São Caetano do Sul is based on its only existing official publication (from 2008), three years after its implementation. Therefore, because of the lack of available updated information, the data provided here, besides of an inevitable lag, may contain some inaccuracies about the current operation of the project. The publication is available at: http://www.tj.sp.gov.br/Download/CoordenadoriaInfanciaJuventude/JusticaRestaurativa/SaoCaetanoSul/Publicacoes/jr_sao-caetano_090209_bx.pdf (Melo et al., 2008).

6This area belongs to the Big Heliopolis Region: Heliopolis, Vila Nova Heliopolis, New City Heliopolis and Heliopolis Island. This region is located in the South Eastern region of São Paulo and is considered the largest slum in the State (with approximately 1 million square meters and 120.000 inhabitants).

7Initially, only three schools participated in the project. In 2007 however all State schools in the city joined the project, so now there are 12 schools taking part.

8Dominic Barter is an international specialist on Nonviolent Communication and Restorative Practices. He works as a consultant to governments, communities, schools, justice systems, private companies and social movements in several countries, as well as to the United Nations (UN). Since 2004 he trains people to work as facilitators on Restorative Justice Projects in Rio Grande do Sul and São Paulo. He is also the coordinator for projects on Restorative Justice in the International Center for Nonviolent Communication.

9Melo et al. (2008) mention that the term "conciliator" was replaced in 2007 by "facilitator of restorative practices" or "facilitator of justice", who is a person trained to act as a facilitator in a restorative circle (p. 13).

10Brazil has: municipal schools (managed by the Mayor); private schools (managed by the private initiative); and State schools (managed by the State/Regional government). Only the last kind participated on the first pilot project.

11In most cases, these are the restorative and the retributive methods. However, when dealing with cases occurring in the school environment, there is also the disciplinary way, which is related to school regulations.

12In the Brazilian criminal justice system, there are three types of criminal prosecution: (a) The public unconditional, when the prosecution is conducted exclusively by the public prosecutor and does not depend on the wish of the victim; (b) The public conditional on the wish of the victim, which requires prior authorization from the victim, so that the prosecution can be conducted by the public prosecutor; and (c) The private prosecution, in which the charge is laid by the victim and his or her lawyer. In most offences, the criminal action is public unconditional, as a general rule, including crimes of high and medium severity. In some crimes of lower seriousness, the action is subjected to the victim's wish, and the private criminal action is used primarily in crimes against honour. The type of criminal procedure always depends on the criminal classification of the wrongdoing.

13All of the following data comes from an article by Aguinsky, Beatriz Gershenson et al. (2008) which presents the data collected in the research developed in the Faculty of Social Work at Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS).

14Exactly as in the adults penal system, young people can "sanction progress" during the execution of the sentence, from the most severe conditions (less liberty), to a less severe (more liberty) situation.

15Lucia Captain and Lucila C. Rose, who are respectively social worker and psychologist at Foundation for Socio-Educational Service (FASE), states that «the absence of the victim in family circles inside FASE was defined according to established criteria, related to the progression of social-educational sanction, therefore, with a range of time at least six months between the commission of the offense and the restorative procedure, and, as a rule, the progressions occur, depending on the seriousness of the offense, taking an average stay of eighteen to twenty-four months of imprisonments. (Capitão & Rosa, 2008, p. 106).

References

Achutti, D. (2009). Modelos contemporâneos de justiça criminal. Justiça terapêutica, instantânea e restaurativa. Porto Alegre: Livraria do Advogado. [ Links ]

Aguinsky, B. G., Hechler, A. D., Comiran, G., Giuliano, D. N., Davis, E. M., Silva, S. E., et al. (2008). A introdução das práticas de justiça restaurativa no sistema de justiça e nas políticas da infância e juventude em Porto Alegre: Notas de um estudo longitudinal no monitoramento e avaliação do programa justiça para o século 21. In L. Brancher & S. Silva (Orgs.), Justiça para o século 21: semeando justiça e pacificando violências. Três anos de experiência da justiça restaurativa na capital gaúcha (pp. 23-57). Porto Alegre, Brasil: Nova Prova. [ Links ]

Andrade, V. R. de. (2003). A ilusão de segurança jurídica: do controle da violência à violência do controle penal (2nd. ed.). Porto Alegre: Livraria do Advogado Editora. [ Links ]

Azevedo, R. (2000). Informatização da justiça e controle social: estudo sociológico da implantação dos juizados especiais criminais em Porto Alegre. São Paulo: IBCCRIM. [ Links ]

Azevedo, R. & Carvalho de, S. (Orgs.). (2006). A crise do processo penal e as novas formas de administração da justiça criminal. Sapucaia do Sul: Notadez. [ Links ]

Bitencourt, C. R. (1993). Falência da pena de prisão. São Paulo: Saraiva. [ Links ]

Braithwaite, J. (2002). Restorative justice and responsive regulation. Oxford: Oxford Press. [ Links ]

Brancher, L. (2008). Apresentação: coordenação do projeto justiça para o século 21. In L. Brancher & S. Silva (Orgs.), Justiça para o século 21: semeando justiça e pacificando violências. Três anos de experiência da justiça restaurativa na capital gaúcha (pp. 1114). Porto Alegre, Brasil: Nova Prova. [ Links ]

Brasil, Lei N. 9.099, de 26 de setembro de 1995. [ Links ]

Brasil, Projeto de Lei n. 7006, de 10 de maio de 2006. [ Links ]

Capitão, L., & Da Rosa, L. A. (2008). Trajetória da FASE em sua conexão com a justiça restaurativa. In L. Brancher & S. Silva (Orgs.), Justiça para o século 21: semeando justiça e pacificando violências. Três anos de experiência da justiça restaurativa na capital gaúcha (pp. 105-112). Porto Alegre, Brasil: Nova Prova. [ Links ]

Carvalho de, S. (2008). Antimanual de criminologia. Rio de Janeiro: Lumen Juris. [ Links ]

Hoyle, C. (2010). The case for restorative justice. In C. Hoyle & Ch. Cunneen (Eds.), Debating restorative justice (pp. 75-81). Oxford and Portland: Hart Publishing. [ Links ]

Marshall, T. (1996). The evolution of restorative justice in Britain. European Journal on Criminal Policy Research, 4(4), 21-43. [ Links ]

Melo, E., Ednir, M. & Yazbek, V. (2008). Justiça restaurativa e comunidade em São Caetano do Sul: aprendendo com os conflitos a respeitar direitos e promover cidadania. São Paulo: Centro de Criação de Imagem Popular. Retrieved on March 20, 2011, from http://www.tj.sp.gov.br/Download/CoordenadoriaInfanciaJuventude/JusticaRestaurativa/SaoCaetanoSul/Publicacoes/jr_sao-caetano_090209_bx.pdf [ Links ]

Pallamolla, R. (2009). Justiça restaurativa: da teoria à prática. São Paulo: IBCCRIM. [ Links ]

Ruggiero, V. (2011). An abolitionist view of restorative justice. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 39(2), 100-110. [ Links ]

Shapland, J. Atk inson, A., Atkinson, H., Colledge, E., Dignan, J. Howes, M., et al. (2006). Situating restorative justice within criminal justice. Theoretical Criminology, 10(4), 505-532. doi: 10.1177/1362480606068876 [ Links ]

Strang, H. (2002). Repair or revenge: Victims and restorative justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Todeschini, T. Nascimento de Oliveira, F., Pons, L., de Moraes, S. & de Oliveira, V. (2008). Central de Práticas Restaurativas do Juizado Regional da Infância e da Juventude de Porto Alegre - CPR-JIJ: aplicação da justiça restaurativa em processos judiciais. In L. Brancher & S. Silva (Orgs.), Justiça para o século 21: semeando justiça e pacificando violências. Três anos de experiência da justiça restaurativa na capital gaúcha. Porto Alegre, Brasil: Nova Prova. [ Links ]

Walgrave, L. (2008). Restorative justice, self-interest and responsible citizenship. Cullompton/Portland: Willan Publishing. [ Links ]

Wunderlich, A. & Carvalho de, S. (Orgs.). (2002). Diálogos sobre a justiça dialogal: teses e antíteses sobre os processos de informalização e privatização da justiça penal. Rio de Janeiro: Lumen Juris. [ Links ]

Wunderlich, A. & Carvalho de, S. (Orgs.). (2005). Novos diálogos sobre os juizados especiais criminais. Rio de Janeiro: Lumen Juris. [ Links ]