Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.11 no.4 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2012

Development of the Forgiveness Schema in Adolescence

Desarrollo del esquema de perdón en la adolescencia

Michelle Girard *

University of Sophia-Antipolis, France

Etienne Mullet **

Institute of Advanced Studies, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, France

* University of Sophia-Antipolis, France. Associate professor. E-mail: michelle.girard@unice.fr

** Institute of Advanced Studies, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, France. etienne.mullet@wanadoo.fr

Recibido: noviembre 11 de 2011 | Revisado: febrero 26 de 2012 | Aceptado: marzo 5 de 2012

Para citar este artículo:

Girard, M. & Mullet, E. (2012). Development of the Forgiveness Schema in Adolescence. Universitas Psychologica, 11 (4), 1235-1244.

Abstract

The study aims to chart the development of the willingness to forgive among adolescents, as a function of seven situational factors: Possibility of revenge, cancellation of harmful consequences, encouragement to forgive from parents and/or from close friends, social proximity with the offender, intent to harm, and presence of apologies. The participants were presented with 16 stories in which an adolescent committed a harmful act against another one. Each participant was asked to rate the degree of personal willingness to forgive in each case on a continuous scale. The effect of the cancellation of consequences factor was the strongest one, and it was stronger among younger adolescents than among older adolescents. The effect of the intent factor was the second strongest factor, and it was stronger among older adolescents than among younger adolescents. The effect of the encouragement factors was moderate (encouragement by friends), or small (encouragement by parents), and no age difference was observed. The effects of the revenge, apologies, and social proximity factors were always weak. An additive-type combination process was observed in each age group.

Key words authors: Adolescents, Forgiveness, Intent to Harm, Cancellation of Consequences.

Key words plus: Situational Factors, Encouragement to Forgive, Presence of Apologies, Social Psychology.

Resumen

El objetivo del estudio fue describir el desarrollo de la voluntad para perdonar en adolescentes, como función de siete factores situacionales: posibilidad de venganza, anulación de consecuencias perjudiciales, disposición a perdonar a los padres o amigos cercanos, proximidad social con el delincuente, intención de daño y ofrecimiento de excusas. A los participantes se les presentaron 16 historias donde un adolescente había cometido un acto perjudicial contra otro. Caso por caso, se pidió a cada participante valorar en una escala continua el grado de voluntad para olvidar. El efecto de la anulación del factor de consecuencias fue el más fuerte, y mayor entre adolescentes jóvenes en comparación con los de más edad. El efecto del factor intención se ubicó en segundo lugar, siendo más fuerte entre los adolescentes mayores que entre los más jóvenes. El efecto de los factores de disposición a perdonar fue moderado (amigos) o pequeño (padres), y no se encontró diferencia en cuanto a la edad. En todos los casos, los efectos de la venganza, las disculpas y los factores sociales de proximidad fueron débiles. En cada grupo de edad, se observó un proceso de combinación de tipo aditivo.

Palabras clave autores: Adolescentes, perdón, intención de daño, anulación de consecuencias.

Palabras clave descriptores: Factores situacionales, disposición al olvido, ofrecimiento de excusas, Psicología Social.

SICI: 2011-2277(201212)11:4<1235:DOFSIA>2.0.CO;2-V

Forgiveness is a central topic in the adolescents' everyday life (Worthington, 2005). On personality, family, community, and national level, the quality of the relationships adolescents have with their peers and adults is largely determined by the willingness to forgive that they manifest regarding the people or groups who have, intentionally or unintentionally, severely or slightly, durably or temporarily, hurt them. Their attitude towards forgiveness may have important repercussions on the way they behave in their family environment (e.g., family violence), at school (e.g., bullying), on the way they conceive the functioning of institutions (e.g., the educational system, the police, the justice system), on the way they consider certain national events (e.g., mass violence in the suburbs), and on the way they consider certain major international events (e.g., terrorism).

Increasingly social scientists have examined the potential relevance of interpersonal forgiving in human relationships (Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2000; Enright & North, 1998; Govier, 2002; Lamb & Murphy, 2002; McCullough, Pargament & Tho-rensen, 2000; Worthington, 1998, 2005). Denham, Neal, Wilson, Pickering and Boyatsis (2005), who have conducted a complete review of research on forgiveness among children and adolescents, concluded, however, that there have been very few studies on this topic in non-adult samples.

Forgiveness among Children and Adolescents

Leon (1980) examined the effect of intent on moral judgment among children and adolescents. He showed that, for judging the offender's blamewor-thiness, intent information was increasingly taken into account as a function of the participant's age. In a subsequent study, Leon (1982) also showed an effect of admission of responsibility (remorse) on moral judgment among young children (see also Leon, 1984). Darby and Schlenker (1982) examined the effect of apologies on forgiveness among children aged 6, 9, and 12. They showed that more elaborate apologies from the offender resulted in a more forgiving attitude among participants.

The apology effect was, however, much more pronounced in 12-year-olds than in younger children.

Denham et al. (2005) examined the relationship between forgiveness in children and forgiveness in their parents. They reported that: (a) In mothers but not in fathers, forgiveness was correlated with children's forgiveness; (b) Mothers' parenting practices were correlated with children's propensity to forgive, and (c) Both mothers' and children's perceptions of these parenting practices were correlated with children's forgiveness. Similar results were reported by Mullet, Rivière and Muñoz Sastre (2006).

Chiaramello, Mesnil, Muñoz Sastre and Mullet (2008) showed that the three constructs of forgiv-ingness found in adults (Mullet, Barros, Frongia, Usaï, Neto & Rivière-Shafighi, 2003), propensity to lasting resentment, sensitivity to circumstances, and willingness to forgive, were already in place among adolescents. They also showed that sensitivity to circumstances of the offense and willingness to forgive were weaker among older adolescents than among younger adolescents, and that the tendencies to lasting resentment (and also willingness to avenge), were stronger among older adolescents than among younger ones.

Enright and his developmental psychology group conducted experimental studies on the progress of reasoning on forgiveness (Enright, Santos & Al-Mabuk, 1989; see also Enright, 1991, 1994; Enright, Gassin & Wu, 1992). His theory was modeled after Kohlberg's (1976) development of moral reasoning theory (see also Spidell & Liberman, 1981). Each stage in Kohlberg's model corresponded with one and only one stage in Enright's model.

In the lowest stages — Revengeful Forgiveness (Level 1) and Restitutional Forgiveness (Level 2) — forgiveness is conceived as only occurring after the wrongdoer has been subjected to revenge or appropriate punishment. In the middle stages — Ex-pectational Forgiveness (Level 3), and Forgiveness as Social Harmony (Level 4) — forgiveness is conceived as being granted only if pressures from significant others are present. It is only in the highest stage of the model — Forgiveness as Love — that forgiveness is conceived as an unconditional attitude and that is seen as promoting a positive regard and good will.

The procedure used in Enright's studies to test his model was also borrowed directly from Kohlberg (1976). Two dilemmas used by this author were taken and slightly altered in order to study the reasoning on forgiveness. These were the well-known "Heinz dilemma", and the "Escaped Prisoner dilemma". A set of questions, devised to correspond with one and only one level of forgiveness development, was also presented to each participant in an interview format.

The mean score observed in 9-to-10-year-old participants was close to Level 2: Restitutional Forgiveness. On average it can be said that young participants were willing to consider that forgiveness can occur only until what had been taken away, has been properly replaced or compensated. This corresponded with what Enright called a pre-forgiveness stage. The mean score observed in 15-to-16-year-old participants was close to Level 3: Expectational Forgiveness, thus, on average, young adolescents were willing to think that forgiveness occurs as a consequence of favorable attitudes expressed by others close to him, even if what had been taken away, had not been restored (for 12-to-13-year-old participants, the mean score was located between the two). Finally, the mean score observed in college students and in adults was close to Level 4: Forgiveness as Social Harmony. This means that young and middle aged adults, were willing to think that forgiveness happened as a consequence of religious or philosophical attitudes, without any intervention of family and friends, even if restitution has not occurred. Few people were classified in the Forgiveness as Love stage level (seven adults, for at least one dilemma).

The Present Study

The aim of the present study was to complement Enright et al.'s (1989; see also Huang, 1990; Park & Enright, 1997) developmental study by exploring personal willingness to forgive in specific circumstances. In other words, in those which information about the offender's identity, level of intent, and subsequent behavior (e.g., apologizing), as well as information on the possible cancellation of consequences and others' attitudes, were available. The method was a variant of the vignette procedure used by Enright et al. (1989). Instead of asking the young participants to verbalize their answers, they were simply asked to make a mark somewhere along a response scale. This method had already proved useful for examining willingness to forgive among adults (Girard & Mullet, 1997; Mullet, Rivière & Muñoz Sastre, 2007).

The transgression situation that was chosen for the present study was the damaging of an adolescent's portable music player (e.g., iPod or Walkman) by one of his or her peers. The different circumstances of this situation orthogonally varied. These components were chosen in order to match, as closely as possible, the different stages proposed by Enright: (a) Revenge; (b) Cancellation of consequences; (c) Encouragement to forgive from parents and/or close friends; (d) Social proximity, (e) Intent to harm and (f) Presence of apologies.

Hypothesis

The first hypothesis' set were based on the findings by Enright et al. (1989), Leon (1980, 1982) and Darby and Schlenker (1982). According to Enright et al. (1989), most young adolescents are at a restitution stage of reasoning about forgiveness. As a result, our first hypothesis was that the effect of the revenge factor on willingness to forgive should be stronger among younger adolescents than among older adolescents. Our second hypothesis was that the effect of the cancellation of consequences factor on willingness to forgive should be stronger among younger adolescents than among older adolescents.

According to Enright et al. (1989), most middle-aged adolescents are at an expectation stage of reasoning about forgiveness. As a result, our third hypothesis was that the effect of the encouragement to forgive factors on willingness to forgive should be stronger among middle-aged adolescents than among younger and older adolescents. And our fourth hypothesis was that the effect of the social proximity factor on willingness to forgive should be stronger among middle-aged adolescents than among younger and older adolescents.

According to Leon (1980), the intention factor is increasingly taken into account during adolescence. Thus, our fifth hypothesis was that the effect of the intention factor on willingness to forgive should be stronger among older adolescents than among younger adolescents. According to Darby and Shenkler (1982, see also Leon, 1982), apologies have a stronger effect among older adolescents than among 12 year-olds. Therefore, our sixth hypothesis was that the effect of the apology factor on willingness to forgive should be stronger among older adolescents than among younger adolescents.

The second hypothesis' set were based on previous findings by Girard, Mullet and Callahan (2002) and Chiaramello et al. (2008). According to Girard et al. (2002), the structure of the forgiveness schema; that is, the combination rule implemented in forgiveness judgments is an additive-type one. In other words, there is no interaction between factors. As a result, our seventh hypothesis was that the effects of the factors that can be found significant should not interact in any of the age groups considered.

According to Chiaramello et al. (2008), the overall level of willingness to forgive is lower among middle-aged adolescents than among young adolescents. As a result, our eighth hypothesis was that, overall, the mean willingness to forgive judgments should be lower among 13-14 year-olds than among 11-12 year-olds.

Method

Participants

The sample was composed of 159 participants (83 females and 76 males). All participants were volunteers and lived in France. Their age ranged between 11 and 18 and they all came from the same type of secondary schools. The sample was divided into four age subgroups: (a) 43 very young adolescents (22 females and 21 males) aged 11-12 (b) 34 young adolescents (17 females and 17 males) aged 13-14; (c) 38 middle-aged adolescents (21 females and 17 males) aged 15-16, and (d) 44 older adolescents (23 females and 21 males) aged 17-18. The four groups were made equivalent regarding social class and geographic residence.

Material

The material consisted of 16 cards that displayed a short story and an answer scale. Each story contained seven critical items of information, in the following order: (a) The social proximity between the offender and the offended (sibling or friend); (b) The degree of intent in the act (clear intent vs. no intent) ; (c) Apologies/contrition for the act (begged for forgiveness vs. did not beg for forgiveness); (d) The encouragement to forgive from parents; (e) The encouragement to forgive from friends and (f) The degree of cancellation of consequences (no cancellation vs. complete cancellation). The 16 stories were obtained by orthogonal crossing of the seven factors in a Latin-square design. Using the findings by Girard et al. (2002), three of the three-way interactions that were known to be non-significant were confounded with three main effects. Two typical stories are given below.

Typical story 1. "David has a new portable music player. His brother, Romain, who would like to listen to music, takes it. Unfortunately, the music player falls on the ground. As a result, it is no longer functioning. Romain is truly sorry about what happened, he immediately apologies and begs for forgiveness from David. Later, David's parents, informed about what happened, encourage him to forgive his brother. David's friends have also encouraged him to forgive Romain. The portable music player is now repaired, and works again. If you were David, to what extent do you think you would be willing to forgive Romain?" This story illustrates the combination of the following levels: Sibling/No intent to harm/Presence of apologies/No revenge/ Encouragement from parents and friends/Complete cancellation of consequences.

Typical story 2. "Benjamin has a new portable music player. His friend, Nicolas, who is clearly jealous takes it, and intentionally drops it on the floor. The music player falls to the ground, and as a result it is no longer functioning. Following the incident, Nicolas behaves as if nothing had happened. Benjamin avenges himself by puncturing the tires of Nicolas' bike. The music player is not repaired yet, and it is still not functioning. If you were Benjamin, to what extent do you think you would be willing to forgive Nicolas?" This story illustrates the combination of the following levels: Friend/Intent to harm/Absence of apologies/Revenge/No encouragement from parents and friends/Consequences still present. Each story was followed by a large, 24 cm response scale with "I am sure I won't forgive" at the left and "I am sure I would forgive" at the right. The offenders and victims were always males.

Procedure

Each participant responded individually to the whole set of 16 cards, generally at school. First, as recommended by Anderson (1996), the person conducting the experiment explained to each participant what was expected from him/her in a so-called familiarization phase. The participant read out-loud the 16 stories (in which an adolescent committed a harmful act against another peer). After each story was read, the person conducting the experiment reminded the participant of the seven critical items of information it contained. The participant then rated the degree of personal willingness to forgive in each case. After the completion of the 16 ratings, the participant was allowed to compare his/ her responses and change them.

During the subsequent experimental phase (Anderson, 1996), the 16 stories were presented again (in different order for each participant). It was no longer possible to compare responses or to go back and make changes as in the familiarization phase. No time limit was imposed.

Results

Each rating by each participant in the second phase of the experiment was converted to a numerical value expressing the distance (measured with a ruler) between the point on the response scale and the left anchor, serving as the origin. These numerical values were then subjected to graphical and statistical analyses. Seven three-way ANOVAs were performed. Their basic design was Participant's age x Participant's Gender x Factor of interest (e.g., Revenge, Intent, or Apologies), 2 x 2 x 2 (the first two factors were between-subject factors).

The participants' answers covered the entire range of the response scale (from 0 to 24). The overall mean response was 16.10. No participant systematically used the "won't forgive" anchor in the response scale.

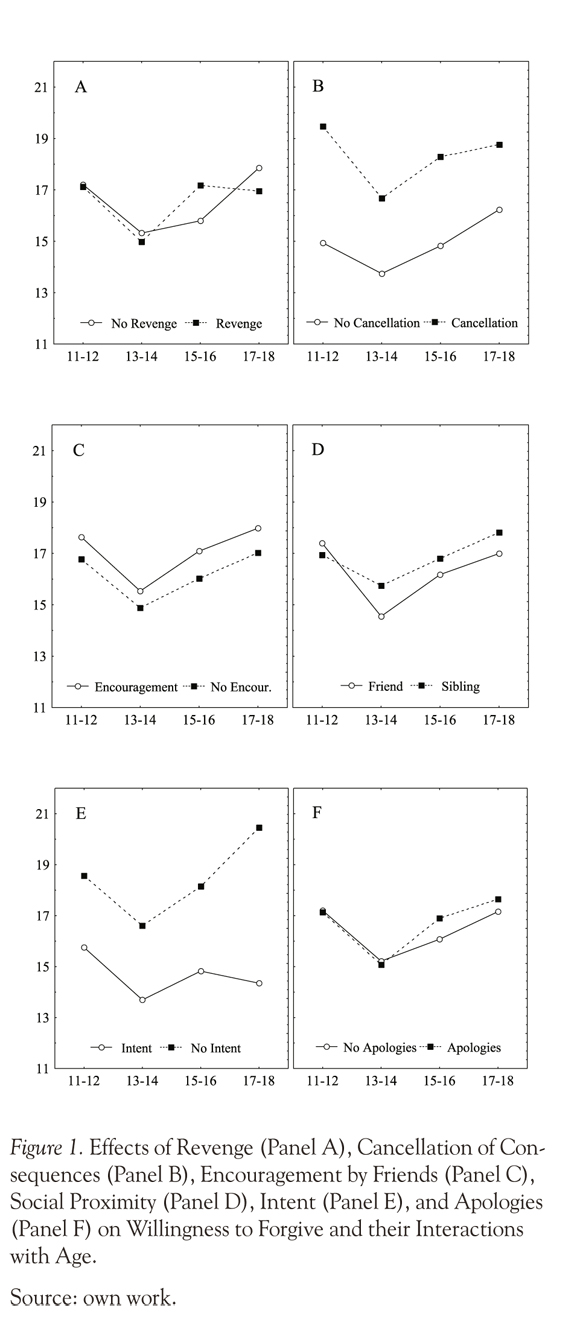

Figure 1 shows the effects of six of the within-subject factors as a function of age. As shown in Panel A, the revenge effect was weak, Cohen's d = 0.01. It was not significant. The Age x Revenge interaction was, however, significant, F(3, 151) = 2.64, p < 0.05. Subsequent analyses showed that the revenge effect was only significant among the 15-16 year-olds. As shown in Panel B, the cancellation effect was strong, d = 0.74. It was significant, F(1, 151) = 101.20, p < 0.001.

The Age x Cancellation interaction was also significant, F(3, 151) = 7.60, p < 0.01. The cancellation effect was stronger among the 11-12 year-olds than among the other age groups. The Gender x Cancellation interaction was also significant, F(3, 151) = 7.61, p < 0.01. The cancellation effect was stronger among males than among females.

As shown in Panel C, the friends' encouragement effect was rather moderate (d = 0.19) but significant, F(1, 151) = 31.25, p < 0.001. The Age x Encouragement interaction however was not significant. The results for the parents' encouragement (not shown, d = 0.10) were of the same form, F(1, 151) = 8.50, p < 0.01. As shown in Panel D, the social proximity effect was weak (d = 0.08) but significant, F(1, 151) = 5.11, p < 0.05. The Age x Social Proximity interaction was not significant.

As shown in Panel E, the intent effect was strong (d = 0.85) and significant, F(1, 151) = 105.16, p < 0.001. The Age x Intent interaction was also significant, F(3, 151) = 4.82, p < 0.01. The intent effect was stronger among the 17-18 year-olds and weaker among the 11-12 year-olds than among the other age groups. The Gender x Intent effect was also significant, F(1, 151) = 6.49, p < 0.02. Finally, as shown in panel F, the apology effect was weak, d = 0.06. It was not significant. Subsequent analyses showed that this effect was slightly stronger among the 15-18 year-olds than among the 11-12 year-olds, but the interaction was only marginally significant, F(1, 151) = 3.18, p < 0.08. The Gender x Apologies interaction was also significant, F(3, 151) = 7.94, p < 0.01. The apology effect was stronger among males than among females.

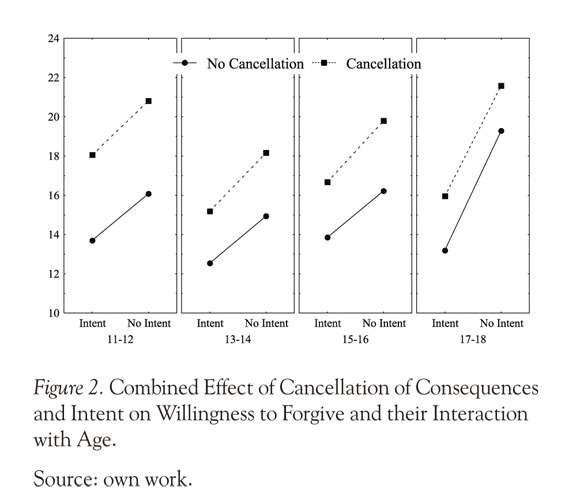

Figure 2 shows the combined effect of the two factors with the strongest effect: Intent and cancellation. The Latin-square design allowed independent assessment of all two-way interactions. All sets of curves were approximately parallel; that is, the two effects combined in an additive way. The Intent x Cancellation and the Age x Intent x Cancellation interactions were not significant. No other two-way interaction was found significant.

Finally, a comparison was made between the overall mean score observed among 11-12 year-olds and the score observed among the 13-14 year-olds. The difference was significant at p = 0.06, F(1, 75) = 3.65. A subsequent planned comparison was conducted between overall mean score observed among the 13-14 year-olds on the one hand, and the three other age groups on the other hand. The age effect was significant, F(1, 155) = 5.09, p < 0.05. The score of the 13-14 year-olds (M = 15.21) was significantly lower than the scores obtained for the three other age groups ( M = 17.09).

Discussion

The present study aimed at developing a chart on the willingness to forgive among adolescents, as a function of seven factors shown to be important in previous developmental studies (Darby & Schlenker, 1982; Enright et al., 1989; Leon, 1980): Revenge, cancellation of harmful consequences, encouragement to forgive from parents and/or close friends, social proximity, intent to harm and presence of apologies.

The first hypothesis was that the effect of the revenge factor should be stronger among younger adolescents than among older ones. This was not observed. Overall, the effect of the revenge factor was weak: It was only moderately present among the 15-16 year-olds. The participants in general did not consider that taking revenge would be a determinant of willingness to forgive. This finding supports the view that forgiveness and revenge are antithetical (Enright, 1991). Adolescents as young as 11 years old seem to share this view. This finding is also in agreement with Chiaramello et al.'s (2008) results showing that willingness to avenge and willingness to forgive formed two separate factors, even among young adolescents.

The second hypothesis was that the effect of the cancellation of consequences factor should be stronger among younger adolescents than among older ones. This is what was observed. Overall, the effect of the cancellation factor was strong (and strongest as compared to other effects). This finding is coherent with previous findings observed among adults in Western cultures (Gauché & Mullet, 2005; Girard & Mullet, 1997; Mullet et al., 2007) as well as in non-Western cultures (Ahmed, Azar & Mullet, 2007; Azar, Mullet & Vinsonneau, 1999).

The third hypothesis was that the effect of the encouragement to forgive factors should be stronger among middle-aged adolescents than among younger and older ones. This was not observed. Overall, the effect of the encouragement factors was moderate (encouragement by friends), or small (encouragement by parents). This last finding is coherent with previous findings observed among adults in Western cultures (Girard & Mullet, 1997). These effects were clearly of the same size in each of the four age groups.

The fourth hypothesis was that the effect of the social proximity factor should be stronger among middle-aged adolescents than among younger and older. This was not observed. Overall, the effect of the social proximity factor was weak (and only detectable among the two older groups). Recent findings by Paleari, Regalia and Fincham (2003) showed that willingness to forgive in adolescents partly depends on the quality of the relationship with the offender. However, in this study the offender was the adolescent's parents (not another adolescent).

The fifth hypothesis was that the effect of the intent factor should be stronger among older adolescents than among younger adolescents. This is what was observed. Overall, the effect of the intent factor was strong. As compared with the other effects, it was the second strongest factor. This finding is consistent with previous findings observed among adults in Western cultures (Gauché & Mullet, 2005; Girard & Mullet, 1997; Mullet et al., 2007) as well as in non-Western cultures (Ahmed et al., 2007; Azar et al., 1999).

This finding is also consistent with findings by Coleman and Byrd (2003) showing a strong link among 7th and 8th graders between self-reported intentional harm from others and interpersonal forgiveness.

The sixth hypothesis was that the effect of the apology factor should be stronger among older adolescents than among younger adolescents. This is what was observed. However, overall, the effect of this factor was weak. This finding is at variance with previous findings observed among adults (Azar et al., 1999; Girard & Mullet, 1997). In these studies, the apology factor was not the dominant factor but nevertheless it was always an important one. The reason of this apparent inconsistency probably lies in the type of presented scenarios. Context effects have recently been studied in a systematic way: Gauché and Mullet (2005) have found that the apology factor plays a more important role in a physical aggression context, than in a pure psychological harm context. In the case of a damaged property context, as in the present study, the impact of apologies may still be less important. This hypothesis would need to be explored in future studies.

The seventh hypothesis was that the effects of the factors found significant would not interact; that is, an additive-type combination process was expected at each age group. This is what was observed. This finding is consistent with previous observed in studies specifically devoted to the determination of the algebraic structure of the forgiveness schema (Girard et al., 2002).

Finally, the eighth hypothesis was that mean willingness to forgive judgments should be lower among 13-14 year-olds than among 11-12 year-olds. This is what was observed, but the difference was only marginally significant. An interesting, nonmonotonic developmental trend was, however, observed. Willingness to forgive was weaker at 1314 years than at any other age. This observation helps resolve the apparent contradiction between Girard and Mullet's (1997) findings showing that, among adults, willingness to forgive increases with age, and Chiaramello et al.'s (2008) findings showing that, among young adolescents, willingness to forgive decreases with age. In fact, willingness to forgive reaches its lowest level in early adolescence (from about 11-12 to 13-14 years) and then increases in later adolescence.

In summary, among adolescents aged 11 to 18, the cancellation of consequences factor and the intent factor appeared as the main situational determinants of willingness to forgive, and their effects were additively combined. A clear developmental change was observed regarding the balance of these factors: (a) The cancellation of consequences factor was stronger among younger adolescents than among older adolescents, and (b) The effect of the intention factor was stronger among older adolescents than among young ones. This development trend was consistent with what was observed in Leon's (1980) studies on the development of the blame schema. In addition, the effect of the encouragement factors was moderate (encouragement by friends) or small (encouragement by parents), and no age difference was observed. The effects of the revenge, apologies, and social proximity factors were always weak. Some interactions with gender were observed, notably regarding cancellation of consequences, intent, and apologies, but they did not alter the overall developmental pattern.

Limitations

This study has at least four limitations. The main limitation of the current study resides in that, as already emphasized, what we gathered was evidence of differences in reported willingness to forgive. It is possible, therefore, that there are no actual differences in willingness to forgive. In the same way, it must also be stressed that what we have measured in the present study is willingness to forgive, not forgiveness behaviors. In other words, attitudes, that is, how adolescents talk about forgiveness and willingness to forgive, may vary over the course of an adolescent's life in a way that can be different from how forgiveness behaviors themselves, reported or acted, may vary. A second, important limitation of the study resides in the cross-sectional nature of the sample. As a result, the age effect may theoretically be confounded with many other effects, notably cohort experience, and social and historical events. This seems, however, unlikely owing to the short time frame considered in the study.

A third limitation resides in that the absence of the revenge factor observed in the present study may be due to some type of social desirability bias. This limitation, however, does not seem a strong one; as shown by Stuckless and Goranson (1992), social desirability does not affect the responses to revenge questionnaires. A final limitation of the study resides in the sample used. Our sample was composed of European participants (from only one country: France). The present results may nonetheless be generalized to other Western countries. More data, however, is needed, especially from Africa, Asia, and Latin America to show the extent to which the developmental model of forgiveness found in this study may apply to other populations (e.g., Kadima Kadiangandu, Mullet & Vinsonneau, 2001; Suwartono, Prawasti & Mullet, 2007).

References

Ahmed, R., Azar, F. & Mullet, E. (2007). Interpersonal forgiveness among Kuwaiti adolescents and adults. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 24(1), 1-12. [ Links ]

Anderson, N. H. (1996). Unified social cognition. New York: Psychology Press. [ Links ]

Azar, F., Mullet, E. & Vinsonneau, G. (1999). The propensity to forgive: Findings from Lebanon. Journal of Peace Research, 36(2), 169-181. [ Links ]

Chiaramello, S., Mesnil, M., Muñoz Sastre, M. & Mullet, E. (2008). Dispositional forgiveness among adolescents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 5(3), 326-337. [ Links ]

Coleman, P. K. & Byrd, C. P. (2003). Interpersonal correlates of peer victimization among young adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(4), 301-314. [ Links ]

Darby, B. W. & Schlenker, B. R. (1982). Children's reaction to apologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(4), 742-753. [ Links ]

Denham, S. A., Neal, K., Wilson, B. J., Pickering, S. & Boyatsis, C. J. (2005). Emotional development and forgiveness in children. In E. L. Worthington, Jr. (Ed.), Handbook of forgiveness (pp. 127-142). New York: Routledge. [ Links ]

Enright, R. D. (1991). The moral development of forgiveness. In W. Kurtines & J. Gewirtz (Eds.), Handbook of moral behavior and development (Vol. 1, pp. 123-152). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Enright, R. D. (1994). Piaget on the moral development of forgiveness: Identity or reciprocity? Human Development, 37(2), 63-80. [ Links ]

Enright, R. D. & Fitzgibbons, R. P. (2000). Helping clients forgive: An empirical guide for resolving anger and restoring hope. Washington: APA. [ Links ]

Enright, R. D. & North, J. (1998). Exploring forgiveness. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. [ Links ]

Enright, R. D., Gassin, E. A. & Wu, C. -R. (1992). Forgiveness: A developmental view. Journal of Moral Education, 21(2), 99-114. [ Links ]

Enright, R. D., Santos, M. J. D. & Al-Mabuk, R. (1989). The adolescent as a forgiver. Journal of Adolescence, 12(1), 95-110. [ Links ]

Gauché, M. & Mullet, E. (2005). Do we forgive physical aggression in the same way that we forgive psychological harm? Aggressive Behavior, 31(6), 559-570. [ Links ]

Girard, M., Mullet, E. & Callahan, S. (2002). Mathematics of forgiveness. American Journal of Psychology, 115(3), 351-75. [ Links ]

Girard, M. & Mullet, E. (1997). Propensity to forgive in adolescents, young adults, older adults, and elderly people. Journal of Adult Development, 4(4), 209-220. [ Links ]

Govier, T. (2002). Forgiveness and revenge. London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Huang, S. T. (1990). Cross-cultural and real-life validations of the theory of forgiveness in Taiwan, the Republic of China. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, United States. [ Links ]

Kadima Kadiangandu, J., Mullet, E. & Vinsonneau, G. (2001). Forgivingness: A Congo-France comparison. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(4), 504-511. [ Links ]

Kohlberg, L. (1976). Moral stages and moralization: The cognitive-developmental approach. In T. Lickona (Ed.), Moral development and behavior: Theory, research and social issues (pp. 31-53). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [ Links ]

Lamb, S. & Murphy, J. G. (2002). Before forgiving: Cautionary views of forgiveness in psychotherapy. New York: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Leon, M. (1980). Integration of intent and consequences information in children's moral judgments. In F. Wilkening, J. Becker & T. Trabasso (Eds.), The integration of information by children (pp. 112-135). Hillsdale: Erlbaum. [ Links ]

Leon, M. (1982). Rules in children's moral judgments: Integration of intention, damage, and rational information. Developmental Psychology, 18(6), 835842. [ Links ]

Leon, M. (1984). Rules mothers and sons use to integrate intention and damage information in their moral judgments. Child Development, 55(6), 2106-2113. [ Links ]

McCullough, M., Pargament, K. I. & Thorensen, C. (Eds.). (2000). Forgiveness: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Guilford. [ Links ]

Mullet, E., Barros, J., Frongia, L., Usaï, V., Neto, F. & Rivière-Shafighi, S. (2003). Religious involvement and the forgiving personality. Journal of Personality, 71(1), 1-19. [ Links ]

Mullet, E., Rivière, S. & Muñoz Satre, M. T. (2006). Relationships between young adults' forgiveness culture and their parents' forgiveness culture. Journal of Cultural and Evolutionary Psychology, 4(2), 159-172. [ Links ]

Mullet, E., Rivière, S & Muñoz Sartre, M. T. (2007). Cognitive processes involved in blame and blamelike judgments and in forgiveness and forgiveness-like judgments. The American Journal of Psychology, 120(1), 25-46. [ Links ]

Paleari, F. G., Regalia, C. & Fincham, F. D. (2003). Adolescents' willingness to forgive their parents: An empirical model. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3(3), 155-174. [ Links ]

Park, Y. O. & Enright, R. D. (1997). The development of forgiveness in the context of adolescent friendship conflict in Korea. Journal of Adolescence, 20(4), 393-402. [ Links ]

Spidell, S. & Liberman, D. (1981). Moral development and the forgiveness of sin. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 9(2), 159-163. [ Links ]

Stuckless, N. & Goranson, R. (1992). The Vengeance Scale: Development of a measure of attitudes toward revenge. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 7(1), 25-42. [ Links ]

Suwartono, C., Prawasti, C. Y. & Mullet, E. (2007). Effect of culture on forgivingness: A Southern-Asia-Western Europe comparison. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(3), 513-523. [ Links ]

Worthington, E. L., Jr. (1998). Dimension of forgiveness: Psychological research and theological perspectives. London: The John Templeton Foundation Press. [ Links ]

Worthington, E. L., Jr. (Ed.). (2005). Handbook of forgiveness. New York: Routledge. [ Links ]