Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.11 no.4 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2012

Physical-Verbal Aggression and Depression in Adolescents: The Role of Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies

Agresión físico-verbal y depresión en adolescentes: el papel de las estrategias cognitivas de regulación emocional

Lourdes Rey Peña *

Natalio Extremera Pacheco **

Universidad de Málaga, España

* Universidad de Málaga, España. Profesora contratada doctora del Departamento de Personalidad, Evaluación y Tratamiento Psicológico. Facultad de Psicología. E-mail: lrey@uma.es

** Universidad de Málaga, España. Profesor titular del Departamento de Psicología Social, Antropología Social, Trabajo Social y Servicios Sociales. Facultad de Psicología. E-mail: nextremera@uma.es

Recibido: agosto 8 de 2011 | Revisado: octubre 11 de 2011 | Aceptado: mayo 4 de 2012

Para citar este artículo:

Rey, L. & Extremera, N. (2012). Physical-Verbal Aggression and Depression in Adolescents: The Role of Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies. Universitas Psychologica, 11(4), 1245-1254.

Abstract

The present study examined the relationships between the use of cognitive emotion regulation strategies, physical-verbal aggression and depression in a sample of 248 adolescents. Specific emotion regulation strategies such as acceptance, rumination and catastrophizing explained significant variance in depression in adolescents. With respect to physical-verbal aggression, our results showed that the use of self-blame and rumination only predicted levels of aggression in boys but not girls. Regarding gender differences, girls tend to ruminate and to report more catastrophic thoughts than boys. Our findings suggest a profile of cognitive emotion regulation strategies related to physical-verbal aggression and depressive symptoms which might be taken into account in future socio-emotional learning programs for adolescents.

Key words authors: Aggression, Depression, Adolescents, Regulation Strategies.

Key words plus: Development Psychology, Emotion, Cognition, Quantitative Research.

Resumen

El presente estudio examinó la relación entre el uso de estrategias de regulación cognitivo-emocional, la agresividad físico-verbal y la depresión en una muestra de 248 adolescentes. Ciertas estrategias de regulación como aceptación, rumiación y catastrofismo explicaron varianza significativa de los niveles de depresión. Con respecto a la agresividad físico-verbal, los resultados indicaron que el uso de la autoculpa y la rumiación solo predecía la agresividad en los jóvenes pero no en las jóvenes quienes, comparativamente, mostraron mayor tendencia a rumiar y a informar más pensamientos catastrofistas. Los hallazgos sugieren un perfil en el uso de estrategias de regulación cognitivo-emocional que se relaciona con la agresividad físico-verbal y con los síntomas depresivos, el cual podría ser tomado en cuenta en futuros programas de aprendizaje socioemocional en adolescentes.

Palabras clave autores: Agresividad, depresión, adolescentes, estrategias de regulación.

Palabras clave descriptores: Psicología del desarrollo, emoción, cognición, investigación cuantitativa.

SICI: 2011-2277(201212)11:4<1245:PVADIA>2.0.CO;2-8

Introduction

From middle childhood through adolescence, young people face a huge variety of physical transformations, emotional challenges and changes in social relationships (Coleman & Hendry, 2003). Adolescence is one of the most important stages in cognitive-emotional development making it a suitable period to analyze the correlates and concrete mood regulation strategies used. Some studies have found that adolescents experience more intense and frequent emotions than younger or older people (Larson & Lampman-Petraitis, 1989). Moreover, hormonal, neural, and cognitive systems related, in same degree, to mood regulation appear to mature during the adolescence (Spear, 2000). Likewise, there is a good deal of evidence showing a higher prevalence of various forms of psychopathology, including affective and behavioural problem, during the adolescent period. Therefore the use of specific coping strategies and mood regulation abilities implemented in this stage will have a significant impact on emotional well being and subsequent emotional development from adolescence to adulthood (Guarino, 2011; Seiffge-Krenke, 1995). Consequently, as Silk, Steinberg and Morris (2003) suggest, a better understanding of process and strategies involved in emotion regulation during adolescence may help us understand individual differences in psychological maladjustment and behavioural problems in this period of increased risk. In addition, due to the maturation process, young people change how they cope with their problems, from most primary and behavioural coping in childhood, to more internal, and cognitive coping strategies during adolescence and adulthood (Garnefski, Legerstee, Kraaij, Van den Kommer & Teerds, 2002; Ison-Zintilini & Morelato-Giménez, 2008). Garnefsky and colleagues have developed and systematized a conceptual categorization of coping strategies called cognitive emotion regulation strategies (Garnef-ski, Kraaij & Spinhoven, 2001). These strategies mainly involve a stable reasonably style to deal with negative events in our lives which are not as permanent as personality traits. In this regard, in certain situations people may use specific cognitive emotion regulation strategies, which may differ from other strategies that could be used in other different contextual situations. The authors argue that these coping strategies may be changed and learned through psychotherapy, school programs and intervention training or experience, which is a major advantage for learning and development in clinical and educational context. Nine conceptually different cognitive emotion regulation strategies have been distinguished: Self-blame, Other-blame, Rumination, Cata-strophizing, Putting into Perspective, Positive Refocusing, Positive Reappraisal, Acceptance and Refocus on Planning (Garnefski et al., 2001). Self-blame refers to the thoughts of blame to yourself for what you have experienced (Anderson, Miller, Riger, Dill & Sedikides, 1994); Other-blame refers to thoughts of putting the blame of what you have experienced on others (Tennen & Affleck, 1990); Rumination refers to thinking all the time about the feelings and thoughts associated with the negative event (Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker & Larson, 1994); Catastrophizing refers to explicitly emphasizing the terror of the experience (Sullivan, Bishop & Pivik, 1995); Putting into Perspective refers to thoughts of playing down the seriousness of the event when comparing to other (Allan & Gilbert, 1995); Positive Refocus-ing, refers to thinking of other, joyful and pleasant matters instead of the actual event (Endler & Parker, 1990); Positive Reappraisal refers to thinking of attaching a positive meaning to the event in terms of personal growth (Carver, Schei-er & Weintraub, 1989; Spirito, Stark & Williams, 1988); Acceptance refers to thoughts of resigning to what has happened (Carver et al., 1989); and Refocus on Planning, refers to thinking about what steps to take in order to deal with the event (Carver et al., 1989; Folkman & Lazarus, 1988). Several studies have found that all these cognitive emotion regulation strategies are associated with different psychopathologies, depression or psychological maladjustment (Garnefski, Kraaij & van Etten, 2005; Martin & Dahlen, 2005; Schroevers, Kraaij & Garnefski, 2007). Specifically, a number of recent findings have shown that some cognitive emotion regulation strategies considered inappropriate such as self-blame, rumination, catastrophizing, show more strong relations with indicators of emotional problems such as anxiety or depression (Garnefski et al., 2001, 2002; Garnefski, Boon & Kraaij, 2003; Kraaij et al., 2003). In the present study we analyzed, as a first objective, the relationship between these cognitive emotion regulation strategies and two indicators of psychological well being in adolescence, such as depression and physical and verbal aggressive behaviour.

On the other hand, it is widely recognized in the epidemiological literature that women are twice as likely as men to suffer mood disorders (Hyde, Mezulis & Abramson, 2008; Kessler, 2006; Russo & Tartaro, 2008). Although several explanations from biological, sociological and educational perspectives have been proposed to explain these gender differences (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003), some research suggests that the differential use of coping strategies by women and men might explain, in part, gender differences in the appearance and maintenance of emotional disorders both in adolescence and adulthood (Matud, 2004; Ptacek, Smith, Espe & Dodge, 1994). In relation to aggressive behaviour, for example, differences in coping strategies employed could explain the greater tendency toward verbal and physical aggression in boys than in girls (Bjõrkqvist, 1994; Burton, Hafetz & Henninger, 2007). Gender differences in cognitive emotion regulation strategies have been analyzed in adults, finding that women use more often than men strategies such as Rumination, Catastrophizing and Positive Refocusing (Garnefski, Teerds, Kraaij, Legerstee & Van den Kommer, 2004). However, as far as we know, no research has examined these gender differences in Spanish adolescent population. Our second objective is to examine gender differences in the use of these cognitive emotion regulation strategies and in which magnitude these strategies predict levels of depression and physical and verbal aggression in Spanish adolescents.

Method

Sample

The sample consisted of 248 adolescents aged between 11 and 18 years (M = 13.99; SD = 1.6), of whom 116 (43%) were boys and 132 (53.2%) were girls who attended different public schools in Málaga (Spain). The educational levels were as follows: 19.4% of the students attended 6° primary course; 17.7% attended 2° ESO course; 46.4% attended 3° ESO course; 14.9% attended 4° ESO course and 1.6% attended secondary education course. The assessment was carried out in classrooms during the normal school schedule under the supervision of a teacher and one graduate psychology student, with guarantees of the study being purely voluntary and anonymous and with the approval both of the school authorities and the pupils' parents.

Materials

Short Cognitive Emotion Regulation

Questionnaire [short-CERQ] (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006)

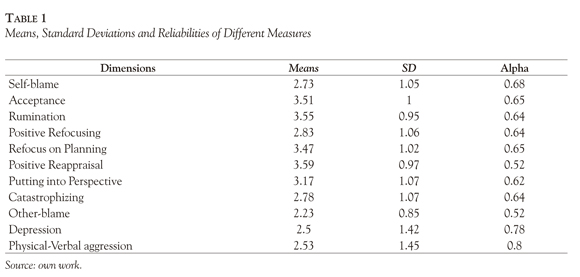

This scale can be used both to measure cognitive strategies that characterize the individual's style responding to stressful events (i.e. by asking how people in general cope with their stress) as well as cognitive strategies that are used in a particular stressful situations (i.e. by asking how people cope with the fact they have experienced a specific stressful life event), in this study we adapted the instructions for using the former way. The short-CERQ is a 18-item questionnaire, consisting of the following nine conceptually different dimensions, each consisting of two items measured on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = almost never to 5 = almost always), and each referring to what someone thinks after the experience of a stressful events. Individual subscale scores are obtained by summing up the scores belonging to the particular subscale (ranging from 2 to 10). The higher the subscale score, the more a specific cognitive strategy is used. The nine different strategies used are: Self-blame (i.e. I feel that I'm the one to blame for it); Other-blame (i.e. I feel that basically the cause lies with others); Acceptance (i.e. I think that I have to accept that has happened); Refocus on Planning (i.e. I think of what I can do best); Positive Refocusing (i.e. I think of nicer things than what I have experienced); Rumination (i.e. I often think about how I feel about what I have experienced); Positive Reappraisal (i.e. I think that the situation also has its positive sides); Putting into Perspective (i.e. I tell myself that there are worse things in life), and Catastrophizing (i.e. I continually think how horrible the situation has been). The short-CERQ has shown adequate psychometrics properties, with most of studies finding Cronbach alpha coefficients over 0.7 for their subscales. For this study, the short-CERQ was translated from English into Spanish using the method of back-translation. The Spanish translation of short-CERQ showed acceptable alpha reliabilities for research purposes ranging from 0.52 to 0.68. The alpha coefficients in this sample for each subscale can be seen in Table 1.

The Children's Depression Inventory: Short Version (CDI:S)

A 10-item self-rated symptom-oriented scale suitable for young adolescents. The CDI:S was developed to provide a psychometrically sound way to quickly screen children and young adolescents for depressive symptoms in which participants are instructed to describe how they have felt during the past 2 weeks. Items are arranged in triplet sentence indicating absence of depression, moderate depression, or severe depression. Following Kovacs (1992), each item was scored on a 3-point scale (ranging from 0 to 2), with all item scores added to yield a total depression score with a range of 0 to 20. We used a well-validated Spanish version (Del Barrio, Roa, Olmedo & Colodrón, 2002). The alpha coefficient in the present sample is in Table 1.

Physical and Verbal Aggression Scale [AFV] (Caprara & Pastorelli, 1993)

Is a 20-item scale that evaluate child's and young adolescents behaviour aimed at hurting others physically and verbally with items such as ''I kick or punch" or " I say bad things about other kids" on a 3-point scale, anchored by 1 (never), 2 (sometimes), and 3 (always). We summed all items to provide a composite score of aggressive behaviour. In this study we used the well-validated Spanish version which has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Del Barrio, Moreno & López, 2001). The alpha coefficient in the present sample is in Table 1.

Results

Descriptive analyses

Means, standard deviations, and Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the study variables are shown in Table 1. The cognitive emotion regulation strategy most used for adolescents was positive reappraisal and the less used was other-blame.

Multiple regression analyses

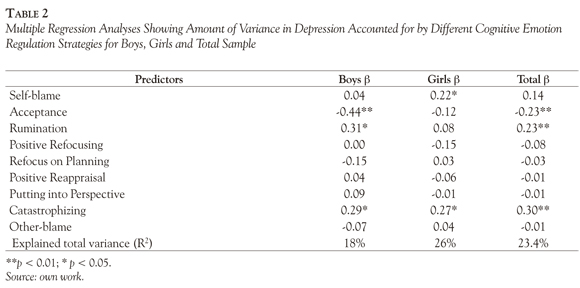

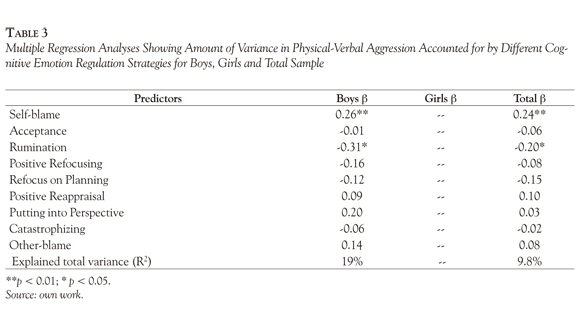

To examine the cognitive emotion regulation strategies which predict levels of depression and physical-verbal aggression and to examine differential pattern as a function of gender in our sample, we conducted a series of multiple regression analyses for the whole sample, boys and girls individually with depression and aggression dimensions as dependent variables and nine coping styles as independent variables.

As can be seen in Table 2, the results show that three regression models (total sample, boys and girls) were significant with an explained variance on depression ranging from 18% for boys and 26% for girls. For the whole sample, the most significant predictors of levels of depression in adolescents were Acceptance, Rumination and Catastrophizing which explained 23.4% of depressive symptoms. The same strategies were significant predictors for boys accounting for 18% of the explained variance. On the other hand, for girls the most significant predictors were Self-blame and Catastroph-izing, which accounted for 26% of depression variance.

Table 3 depicts the regression analyses for physical-verbal aggression; it is noteworthy that the regression model was not statistically significant for girls. None of nine coping styles were significant to predict physical-verbal aggression in girls. On the other hand, the models were significant for boys and the whole sample. In short, self-blame, and rumination were the significant predictors of physical-verbal aggression in boys.

Gender differences

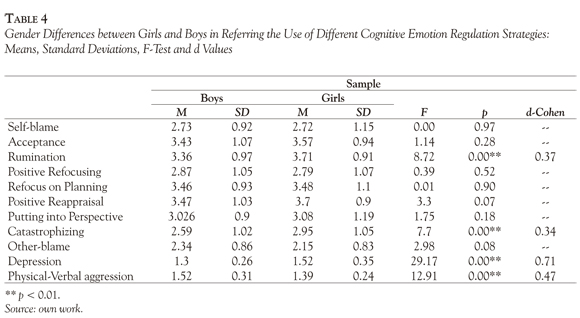

To further analyze the potential gender differences in cognitive emotion regulation strategies, several MANOVA analysis were utilized. We also calculated the effect sizes to describe the magnitude of gender differences (Cohen, 1988). By using Cohen's criteria, an effect size of > 0.20 and < 0.50 was considered small, > 0.50 and < 0.80 medium and > 0.80 large. Similar ranges based on effect sizes of 0.20, 0.50, and 0.80 were considered small, medium and large, respectively. As can be seen in Table 4, results showed that there was a significant overall difference between boys and girls (Wilks'lambda = 0.0807; F(9, 239) = 4.29; p = 0.000).

Univariate F-test showed that the significant differences were in Rumination (F(1,248) = 8.72, p < 0.001, d = 0.37) and Catastrophizing (F(1, 248) = 7.70, p < 0.001, d = 0.34). Specifically, women tended to express greater use of these strategies to the experience of stressful events in their lives. Also, several one-way ANOVAs were used to further analyze the gender differences in depression and physical-verbal aggression. As expected, statistically significant differences were found in depression (F(1,248) = 29.17, p < 0.001, d = 0.71) and aggression (F(1,248) = 12.91, p < 0.001, d = 0.47).

In short, girls informed more depressive symptoms than boys. Boys reported higher levels of physical-verbal aggression than girls. Finally, although not significant, statistical trends were found regarding the use of more positive reappraisal by girls ( p = 0.07) and more other-blame for boys (p = 0.08).

Discussion

The present study examined the contribution of different cognitive emotion regulation strategies on levels of depression and physical-verbal aggression in a sample of Spanish adolescents. It was found that the use of certain cognitive emotional regulation strategies by adolescents significantly predicted their levels of depression and physical-verbal aggression.

The excessive use of specific cognitive emotion regulation strategies such as acceptance, rumination and catastrophizing were associated with higher depressive symptoms. Also, these strategies explained 23% of the variance in depression among adolescents. These results are in line with previous studies in adult samples (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006), demonstrating that adolescents tendency to accept unconditionally problems as if nothing could be done, reflect intrusively on the problem or think that the problems are worse than they really are, considered harmful and maladaptive strategies. With respect to verbal-physical aggression, the results showed that the use of certain strategies of cognitive emotion regulation only predicted levels of aggression in boys but not girls. Specifically, adolescents who informed they use strategies such as self-blame and low rumination reported more levels of verbal and physical aggression in everyday life. It is possible that self-blame leads to frustration due to adolescents beliefs that negative events are, in some degree, caused by themselves, which causes an increase in the emotional arousal that lead them to use aggressive behaviours. Adolescents would behave more aggressively if they have internalized some codes that indicate that such behaviour is appropriate in certain circumstances, as proposed by frustration-aggression theory (Berkowitz, 1989). On the other hand, adolescents who tend not to think reflectively about their emotions and feelings would tend to act more aggressively. These data are consistent with those found in alexithymic individuals or with deficits in emotional processing, which tend to experience higher levels of impulsive aggression (Fossati et al., 2009).

From emotional intelligence theory is considered that a minimum level of attention to emotions are required to process emotional information, and then to understand their meaning, and repair our moods efficiently (Fernández-Berrocal & Ex-tremera, 2008). It is possible that adolescents with low levels of attention to moods show deficits in interpreting the causes of their emotions and led them to act aggressively instead of behaving in a more emotionally intelligent way (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2003).

Our second objective was to analyze the gender differences in depression and physical aggression and to examine the specific regulation strategies used differently by boys and girls. In agreement with previous epidemiological studies, our findings have showed higher levels of depressive symptoms in girls (Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994) and higher significant aggression scores in boys (Ramírez, Andreu & Fujihara, 2001).

With regard to the differential patterns in the cognitive emotion regulation strategies used by girls and boys, the results showed that girls tend to ruminate and to inform more catastrophic thoughts than boys. These findings are in line with previous research in adults showing how women are more likely to focus more on their emotional experience, and to ruminate more about them than men do (Fi-vush & Buckner, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994). In addition, a similar pattern was found in previous studies analyzing the link between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms in adult samples (Garnefski et al., 2004).

On the other hand, catastrophizing, along with self-blame, were strongly linked to depressive symptoms in girls, accounting for more than 25% of the variance in their levels of depression, while in boys acceptance and catastrophizing strategies were the most strongly linked to levels of depression. However, the percentage of variance explained by the cognitive emotion regulation strategies on depression was significantly higher for girls, supporting the hypothesis that the higher rate of depression in girls may be related, to a certain extent to the use of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation which in turn influences their levels of depressed mood.

Several limitations in our study should be mentioned. First, we used self-reported questionnaires for data collection of levels of depression, aggression and coping styles which has obvious biases such as shared method variance. Future studies should collect this information using other sources of information less prone to this type of bias such as the interview process, peer review or reports from parents and/or teachers. Similarly, a correlation design was used which prevents reliable draw inferences about causality between variables, and how potential changes in using different coping strategies might affect to depressive and aggressive symptoms in adolescents over time. Although it is impossible to obtain data of causality, several longitudinal and experimental findings suggest that certain maladaptive regulation strategies are the basis for the emergence and development of mood disorders and psychosocial problems during the period of adolescence (Hughes, Gullone & Watson, in press; Zeman, Cassano, Perry-Parrish & Stegall, 2006).

Despite these limitations, our study suggests a future line of research in order to apply emotional learning in the classroom. There are currently educational programs in both the U.S. and Spain aimed at developing social and emotional skills whose main objective is to reduce aggressive behaviour and disruptive problems in adolescents (Greenberg et al., 2003; Ruíz-Aranda, Fernández-Berrocal, Cabello & Salguero, 2008). Our results suggest several profiles of adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies related with aggressive behaviour and depressive symptoms that might be taken into account in future socio-emotional learning programs. At this respect, we have found the use of specific patterns of cognitive emotion regulation strategies for boys and girls. Further emotional literacy programs might be more effective not being implemented in a generic way but taking into account the specific emotional needs as a function of gender. In this sense, future socio-emotional prevention and intervention youth programs might also consider these results to teach effective cognitive emotion regulation strategies to reduce depressive symptoms and aggressive behaviour or eliminate certain emotional habits that increase these affective and behaviours problems. Undoubtedly, the successful future of our adolescents in different personal, social or familiar fields is linked to the intelligent use of emotions. Increasingly, evidence suggests that this emotional subject is equally or more important than others in school, and requires, for the comprehensive development of our adolescents, a strong collaboration between parents and educators.

References

Allan, S. & Gilbert, P. (1995). A social comparison scale: Psychometric properties and relationship to psychopathology. Personality and Individual Differences, 19(3), 293-299. [ Links ]

Anderson, C. A., Miller, R. S., Riger, A. L., Dill, J. C. & Sedikides, C. (1994). Behavioral and characte-rological attributional styles as predictors of depression and loneliness: Review, refinement, and test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(3), 549-558. [ Links ]

Berkowitz, L. (1989). The frustration-aggression hypothesis: An examination and reformulation. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 59-73. [ Links ]

Bjõrkqvist, K. (1994). Sex differences in physical, verbal, and indirect aggression: A review of recent research. Sex Roles, 30(3-4), 177-188. [ Links ]

Burton, L., Hafetz, J. & Henninger, D. (2007). Gender differences in relational and physical aggression. Social Behavior & Personality, 35(1), 41-50. [ Links ]

Caprara, G. V. & Pastorelli, C. (1993). Early emotional instability, prosocial behavior, and aggression: Some methodological aspects. European Journal of Personality, 7(1), 19-36. [ Links ]

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F. & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267-283. [ Links ]

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Coleman, J. & Hendry, L. (2003). Psicología de la adolescencia (4.a ed.). Madrid: Ediciones Morata, SL. [ Links ]

Del Barrio, M. V., Roa, M. L., Olmedo, M. & Colodrón, F. (2002). Primera adaptación del CDI-S a población española. Acción Psicológica, 1(3), 263-272. [ Links ]

Del Barrio, V., Moreno, C. & López, R. (2001). Evaluación de la agresión e inestabilidad emocional en niños españoles y su relación con la depresión. Clínica y Salud, 12(1), 33-50. [ Links ]

Endler, N. S. & Parker, J. D. A. (1990). Multidimensional assessment of coping: A critical evaluation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), 844-854. [ Links ]

Extremera, N. & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2003). La inteligencia emocional en el contexto educativo: hallazgos científicos de sus efectos en el aula. Revista de Educación, 332, 97-116. [ Links ]

Fernández-Berrocal, P. & Extremera, N. (2008). A review of trait meta-mood research. En A. Columbus (Ed.), Advances in psychology research (Vol. 55, pp. 17-45). San Francisco: Nova Science Publishers. [ Links ]

Fivush, R. & Buckner, J. P. (2000). Gender, sadness and depression: Developmental and socio-cultural perspectives. In A. H. Fischer (Ed.), Gender and emotion: social psychological perspectives (pp. 232-253). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Folkman, S. & Lazarus, R. S. (1988). Manual for the Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press. [ Links ]

Fossati, A., Acquarini, E., Feeney, J. A., Borroni, S., Grazioli, F., Giarolli, L. E., et al. (2009). Alexithy-mia and attachment insecurities in impulsive aggression. Attachment & Human Development, 11(2), 165-182. [ Links ]

Garnefski, N. & Kraaij, V. (2006). Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Personality and Individual Differences, 41(6), 1045-1053. [ Links ]

Garnefski, N. & Kraaij, V. (2006). Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(8), 1659-1669. [ Links ]

Garnefski, N., Boon, S. & Kraaij, V. (2003). Relationships between cognitive strategies of adolescents and depressive symptomatology across different types of life event. Journal ofYouth and Adolescence, 32(6), 401-408. [ Links ]

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V. & van Etten, M. (2005). Specificity of relations between adolescents' cognitive emotion regulation strategies and internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Adolescence, 28(5), 619-631. [ Links ]

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V. & Spinhoven, Ph. (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(8), 1311-1327. [ Links ]

Garnefski, N., Legerstee, J., Kraaij, V., Van den Kommer, T. & Teerds, J. (2002). Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A comparison between adolescents and adults. Journal of Adolescence, 25(6), 603-611. [ Links ]

Garnefski, N., Teerds, J., Kraaij, V., Legerstee, J. & Van den Kommer, T. (2004). Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: Differences between males and females. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(2), 267-276. [ Links ]

Guarino, L. (2011). Adaptación y validación de la versión hispana del Cuestionario de Estilo Emocional. Universitas Psychologica, 10(1), 197-210. [ Links ]

Greenberg, M. T., Weissberg, R. P., O'Brien, M. U., Zins, J. E., Fredericks, L., Resnik, H., et al. (2003). Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. American Psychologist, 58(6-7), 466-474. [ Links ]

Hyde, J. S., Mezulis, A. H. & Abramson, L. Y. (2008). The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychology Review, 115(2), 291-313. [ Links ]

Hughes, E. K., Gullone, E. & Watson, S. D. (in press). Emotional functioning of children and adolescents at risk for depression. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioural Assessment. [ Links ]

Ison-Zintilini, M. S. & Morelato-Giménez, G. S. (2008). Habilidades socio-cognitivas en niños con conductas disruptivas y víctimas de maltrato. Universitas Psychologica, 7(2), 357-367. [ Links ]

Kessler, R. C. (2006). The epidemiology of depression among women. In C. Keyes & S. Goodman (Eds.), A handbook for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences: Women and depression (pp. 22-37). New York: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Kovacs, M. (1992). Children Depression Inventory CDI [Manual]. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems. [ Links ]

Kraaij, V., Garnefski, N., De Wilde, E. J., Dijkstra, A., Gebhardt, W., Maes, S., et al. (2003). Negative life events and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: Bonding and cognitive coping as vulnerability factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 32(3), 185-193. [ Links ]

Larson, R. & Lampman-Petraitis, C. (1989). Daily emotional states as reported by children and adolescents. Child Development, 60(5), 1250-1260. [ Links ]

Martin, R. C. & Dahlen, E. R. (2005). Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression, anxiety, stress, and anger. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(7), 1249-1260. [ Links ]

Matud, M. P. (2004). Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(7), 1401-1415. [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2003). Women who think too much: How to break free of overthinking and reclaim your life. New York: Holt. [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. & Girgus, J. S. (1994). The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin, 115(3), 424-443. [ Links ]

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Parker, L. E. & Larson, J. (1994). Rumiative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(1), 92-104. [ Links ]

Ptacek, J. T., Smith, R. E., Espe, K. & Dodge, K. L. (1994). Gender differences in coping with stress: When stressor and appraisals do not differ. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(4), 421- 430. [ Links ]

Ramírez, J. A., Andreu, J. M. & Fujihara, T. (2001). Cultural and sex differences in aggression: Comparison between Japanese and Spanish students using two different inventories. Aggressive Behavior, 27(4), 313-322. [ Links ]

Ruíz-Aranda, D., Fernández-Berrocal, P., Cabello, R. & Salguero, J. M. (2008). Educando la inteligencia emocional en el aula: el proyecto INTEMO. Revista de Investigación Psicoeducativa, 6(2), 240-251. [ Links ]

Russo, N. F. & Tartaro, J. (2008). Women and mental health. In F. L. Denmark & M. A. Paludi (Eds.), Psychology of women: A handbook of issues and theories (pp. 440-481). Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. [ Links ]

Schroevers, M., Kraaij, V. & Garnefski, N. (2007). Goal disturbance, cognitive coping strategies, and psychological adjustment to different types of stressful life event. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(2), 413-423. [ Links ]

Seiffge-Krenke, I. (1995). Stress, coping, and relationships in adolescence. Mahwah: LEA. [ Links ]

Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L. & Morris, A. S. (2003). Adolescents' emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behaviour. Child Development, 74(6), 1869-1880. [ Links ]

Spear, L. P. (2000). The adolescent brain and age-related behavioural manifestations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 24(4), 417-463. [ Links ]

Spirito, A., Stark, L. J. & Williams, C. (1988). Development of Brief Coping Checklist for use with pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 13(4), 555-574. [ Links ]

Sullivan, M. J. L., Bishop, S. R. & Pivik, J. (1995). The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 7(4), 524-532. [ Links ]

Tennen, H. & Affleck, G. (1990). Blaming others for threatening events. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 209-232. [ Links ]

Zeman, J., Cassano, M., Perry-Parrish, C. & Stegall, S. (2006). Emotion regulation in children and adolescents. Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 27(2), 155-168. [ Links ]