Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Universitas Psychologica

versão impressa ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.12 no.2 Bogotá may./agos. 2013

Public Perception of the Motives that Lead Political Leaders to Launch Interstate Armed Conflicts: A Structural and Cross-Cultural Study

Percepción pública de los motivos que conducen a los líderes políticos para desarrollar los conflictos armados interestatales: Un estudio estructural y transcultural

Hakim Djeriouat *

University of Toulouse, France

Etienne Mullet **

Institute of Advanced Studies, Paris, France

* University of Toulouse, France, Corresponding Authors: Université de Toulouse, Maison de la Recherche, 5 allées Antonio-Machado 31058 Toulouse Cedex 9 France. E-mail: djerioua@univ-tlse2.fr

** Institute of Advanced Studies, Paris, France, Etienne.mullet@wanadoo.fr

Recibido: junio 13 de 2012 | Revisado: diciembre 1 de 2012 | Aceptado: diciembre 15 de 2012

Para citar este artículo:

Djeriouat, H. & Mullet, E. (2013). Public perception of the motives that lead political leaders to launch interstate-armed conflicts: A structural and cross-cultural study. Universitas Psychologica, 12(2), 327-346.

Abstract

The way the people from two culturally very different countries perceive the psychological motives that lead political leaders to launch armed actions against other states was examined. Three types of possible psychological motives, taken from McClelland's (1985) theory of human motivation, were considered: motives associated with the state's power (e.g., increasing the country's economic power), motives associated with other states' political character (e.g., whether neighboring states are relatively peaceful democracies or threatening autocracies), and motives associated with domestic issues (e.g., appearing as a strong leader able to efficiently fight for the security of the country). A total of 442 participants living in Western Europe (France) and 180 participants living in the Maghreb (Algeria) were presented with a Motives of War questionnaire that was created for the present set of studies. Exploratory and confirmatory analyses showed that the hypothesized model of motives holds with the condition that the increasing power motive is divided into two separate motives: one associated with the economy and one associated with the territory. The motives of war tended to be seen as more personal and as more associated with domestic issues among people living in Algeria than among people living in France. Among traditional/ authoritarian people living in France, the motives of war tended to be seen in a more positive light than among liberal people. In contrast, among traditional/authoritarian people living in Algeria, the motives of war tend to be seen in a more negative light than among liberal people.

Key words authors: International Conflicts, Human Motivation, Aggression, Personality, Values, Conservatism.

Key words plus: Public Perceptions, Structural and Transcultural Study

Resumen

Se examina la forma en que las personas de dos países culturalmente muy diferentes perciben los motivos psicológicos que conducen a los líderes políticos a poner en marcha acciones armadas contra otro estados. Tres tipos de motivos psicológicos posibles, tomados de la teoría de McClelland (1985) sobre la motivación humana fueron consideradas: motivos asociados con el estado de poder (e.g., incrementar el poder económico del país), motivos asociados con políticas de otros estados (e.g., si los estados vecinos son relativamente democracias pacíficas o autocracias amenazantes), y motivos asociados con temas domésticos (e.g., aparicencia como un fuerte lidear capar para luchar eficientemente para mantener la seguridad del país). A un total de 442 habitantes de Europa Occidental (Francia) y 180 habitantes en Maghreb (Algeria) se les administró el cuestionario de Motivos de Guerra que fue diseñado para este estudio. Se presenta un análisis exploratorio y confirmatorio que hipotetiza el modelo de motivos mantenidos con la condición que el incremento en el motivo de poder se dividió en dos motivos separados: uno asociado con la economía y otro asociado con el territorio. Los motivos de guerra tienden a ser vistos como más personales y asociados con temas internos entre los habitantes en Algeria que los habitantes en Francia. Entre los tradicional y autoritarios habitantes en Francia, los motivos de guerra tienden a ser percibidos de forma más positiva que entre las personas liberales. En contraste, entre las personas autoritarias o tradiciones que habitan Algeria, los motivos de guerra tienen a ser vistos de forma más negativa que entre las personas liberales.

Palabras clave autores: Conflictos internacionales, motivaciones humanas, agresión, personalidad, valores, conservatismo.

Palabras clave adicionales: Percepciones públicas, estudio estructural y transcultural.

doi:10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY12-2.plac

Most of the time, most countries are at peace with their neighbors. They continuously interact in multiple ways with them through, notably, the circulation of goods (e.g., manufactured products), people (e.g., tourism) and information (e.g., scientific collaboration). Tensions inevitably exist between states but they are, most of the time, resolved using peaceful means. From time to time, however, conflicts of interest between states arise, which apparently cannot be handled in a peaceful way. In these cases, these states' political leaders decide to resort to armed actions as a way of solving them, and they justify their decisions with arguments demonstrating that, owing to circumstances, war was inevitable (Moerk & Pinkus, 2000). Some people believe in their leaders but other people think the other way: They attribute to their leaders hidden and personal motives.

As wars are costly in terms of human lives and material destruction, scholars have tried to understand the causes of interstate-armed conflicts, with the aim of preventing their occurrences as much as possible. Indeed, many peace researchers are concerned with delineating the conditions for sustainable peace in the world (López López & Sabucedo, 2007). Early historians (e.g., Thucydides), and philosophers of the Enlightenment (e.g., Hobbes), have, among others, suggested various reasons for explaining leaders' decisions to go to war. Present day scholars use empirical methods to shed light on the causes and conditions of war initiation.

Contrary to previous studies, the present set of studies does not investigate the objective causes/ reasons of wars. The present set of studies is about the way people perceive the psychological motives that lie behind the leaders' decisions. In other words, it was aimed at delineating the mental model(s) people have in mind for judging the motives that lay behind the many armed conflicts that are continuously reported in the media. Study 1 was conducted in Western Europe. Using Mc-Clelland's (1985) theory of human motivation as a framework, it (a) inventoried the motives that, in people's views, could lead leaders to resort to military actions against other states, (b) examined the structure of these perceived motives using exploratory techniques, and (c) assessed the associations between these perceived motives and measurements classically used in the peace psychology literature. Study 2 tested the robustness of the model that was evidenced in Study 1 using another sample of participants, and using confirmatory techniques. It also tested the robustness of the relationships that were assessed in Study 1. Finally, Study 3 tested, using confirmatory techniques, the robustness of the model of perceived motives on a sample of participants living in the Maghreb. It also re-examined, in this new sample, the relationships between the model and the various measurements that were used in the previous studies.

The general approach taken is that conflicts do not start by themselves: "The selection of war and peace is a choice that is initiated, conducted, and concluded by individual leaders" (Bueno de Mesquita, 1981, p. 5). At one point in time, a head of state, in agreement with the government of this state, declares war on another state. This does not mean that the objective factors highlighted in the objective theories have no effect. This means that these factors must find their psychological translation, in the form of personally experienced reasons by rulers to actually exert their effect. It also means that a class of reasons, purely psychological, probably lies outside the reasons analyzed by the objective theories: "For good or ill, statesmen can make a critical difference. Without Hitler, there may well have been no Holocaust. Without Milosevic, there might not have been the brutalities of Bosnia and Kosovo" (Prager, 2003, p. 211).

The public opinion /foreign military policy linkage literature suggests that social attitudes related to a potential use of force are based both on dis-positional and situational variables (e.g., Chittick & Freyberg-Inan, 2001; Herrmann, Tetlock & Visser, 1999). In their seminal work, Chittick and Feyberg-Inan (2001, p. 32) concluded that, although interacting effects of disposition and situation remain relevant, basic human motivations are at the cornerstone of foreign policy opinion. Actually, many scientists analyzed policy preferences within this framework (e.g., Cottam, 1977; Wolfers, 1962). For instance, McClelland's theory of motivation fruitfully accounted for various policy opinions and decisions among students that experimentally deal with international crisis situations (Peterson, Winter & Doty, 1994). This theory also successfully accounts the motives of belligerents and peaceful leaders throughout history (Winter, 1993, 2007). In particular, Winter (1993) showed that war prone-ness is synchronically related to high power motive imagery and low affiliation motive imagery of political leaders. In contrast, war ending and peaceful resolution of disputes occur when the inverse pattern takes place. Based on these studies, we put forward the idea that McClelland's theoretical framework will enable us to conveniently describe how people conceive leaders' motives to launch international conflicts.

McClelland's Theory of

Human Motivation

In his theory of human motivation, McClelland (1985) defined three general psychological basic needs: need for power, need for achievement, and need for affiliation.

Need for Power

People's need for power is expressed by concerns about "having impact, control or influence on another person, group or the world at large" (Winter, 1993, p. 537). People scoring high in need of power tend to take strong, forceful actions over others, they try to regulate and control others or at least to influence them, to give unsolicited advices or help, and want to impress others (Winter, 1993).

Previous studies conducted in the "objective reasons for wars" framework, have shown that state leaders' need for power was associated with the initiation of interstate conflicts (Winter, 1993). Each state, as any living organism, ultimately aims at preserving its existence. Preserving ones' existence supposes having the ability to develop oneself and to oppose any destructive action from the environment. In other words, it supposes power in order to ensure satisfactory domestic capability to meet the population needs (Choucri & North, 1975, 1989) and maximal security (Waltz, 1979). The power of a state can arise from demographic development, economic development, territorial expansion or recuperation. As power is relative, however, it also depends on the neighboring states' power. At times, leaders can feel that the only way for achieving security, that is, for attaining enough relative power, is to attack one of the neighbors, and seize part of its territory, resources, and population. Then, from the perspective of leaders, and particularly leaders showing high need for power, securing enough power for achieving security may constitute a reasonable motive for launching a war (Mearsheimer, 2001).

Need for Achievement

According to McClelland (1985), people's need for achievement is expressed by concerns about a standard of excellence. People scoring high in need for achievement tend to be (or to try to be) successful in competition, frequently expressed by words or actions that reflect their concern for excellence, they disproportionately react to failures, and wish to carry out some unique, unprecedented accomplishment (Winter, 1993).

Scholars working in the "objective reasons for wars" framework have shown that powerful states tend to more frequently enter in armed conflicts than less powerful states (e.g., Bremer, 1980). In addition, the majority of initiators have been found to be stronger than the assaulted countries, and have a positive expected utility rate prior to the outbreak of the conflict (Bueno de Mesquita, 1981). These findings may lead one to believe that one reason for launching an armed conflict is the certainty of winning on the battlefield. However, the certainty to be the winner cannot be seen as a root motive for launching a war, except in the case where the leaders are, owing to their concern for personal achievement as politicians, or for some ideological reason (e.g., aristocratic militarism, cult of personality) or economic reason (e.g., enduring bad economic results), in strong need of popularity/admiration among its people and abroad (Most & Starr, 1989). In these cases, the leaders' objective is really to be involved in a war that can be won, and the increase in power (see previous point) becomes a simple means. What the leaders really try to gain (or regain) in these cases is personal achievement and the associated possibility to maintain themselves in power for some more years.

Need for affiliation

According to McClelland (1985), the people's need for affiliation is expressed by concerns about "establishing, maintaining or restoring friendship or friendly relations among people or groups" (Winter, 1993, p. 537). People scoring high in need for affiliation tend to express positive feelings towards other ones, other groups or other nations, tend to express negative feeling about separation or disruption, and are willing to help or provide first-aid to people or groups that are perceived as being in danger, and to defend them against enmity (Winter, 1993). Studies conducted in the "objective reasons for wars" framework has repeatedly shown that between mature democracies, the armed conflicts tend to occur with considerably less frequency and severity than when at least one of the state in the pair of states is an autocracy (e.g., Hewitt & Young, 2001), although democracies are, overall, not less frequently involved in armed conflicts that autocracies (Chan, 1984; Morgan & Schwebach, 1992). Despite the robustness of this finding, it is difficult to conceive that the leaders of a democratic state would reasonably decide to attack an autocratic state just because it is not a democracy, or symmetrically that the leader of an autocratic state would decide to attack a democratic state just because it is not an autocracy.

There have been recent cases, however, that show that this is not impossible. In these cases, the basic motive for war seems to be associated with security concerns. As indicated above, the major concern of any state is to ensure its perpetuation. As a result, the leaders of a democratic state can reasonably think that security can be better achieved in an international environment populated by many democratic states that share its core values than in an environment populated by many autocratic states (Dixon, 1994). In other words, if relative power indisputably matters as regards to security, good (democratic) neighborhood, it also constitutes a non-negligible security factor (Sobek, Abouharb & Ingram, 2006). In other words, living among states with which positive, friendly relations are possible is better than living among a set of neighboring states with which affiliation is made impossible.

In Summary

Despite the multiplicity of factors that have been suggested since Thucidydes to the present day, three basic psychological motives for which leaders decide to go to war can be found in the literature. All of these motives are, unsurprisingly, associated with security (political leader's security or state's security). These psychological motives are: (a) gaining power (e.g., through the seizing of another state's resources and territory), (b) gaining popularity and prestige (through the victory itself, even if the costs of the war have largely exceeded its benefits), and (c) securing good (democratic) neighborhood (e.g., by exporting democratic structures abroad).

Possible Correlates of Public

Perception of the Motives of War

Several measurements have been found to accurately predict dispositional attitude towards war. Conservatism (measured by both Right Wing Authoritarianism and Social Dominance Orientation Scales) has been shown to be positively associated with support for military response (Cohrs, Maes, Moschner & Kielmann, 2005a; McFarland, 2005; Nelson & Milburn, 1999; Sidanius & Liu, 1992). Heskin and Power (1994) pointed out that whereas conservatism predicted support for war, liberalism predicted opposition to war. In the literature, there are findings that link a moral justification to conservatism and the attitude towards war. The positive attitude towards war is associated with the readiness to find moral justifications of war (McAlister, 2001). Also, Jackson and Gaertner (2010) have recently evidenced the mediating effect of moral justification in explaining the relationship between conservatism and the support for war. Values are also important in explaining the war-related attitudes. It has repeatedly been found that the conservative values were positively related to militaristic attitudes (e.g., Cohrs, Maes, Moschner & Kielmann, 2005a).

Study 1

As previously indicated, Study 1 was aimed at (a) systematically inventorying the psychological motives that could lead political leaders to resort to military actions against other states, (b) examining the structure of these motives, and (c) exploring the associations between the different sets of motives and the classical measurements used in personality psychology (personality factors, aggression), and in the peace psychology literature (pro-war attitudes, social dominance orientation, authoritarianism). This study was conducted in France.

Regarding the structure of the perceived psychological motives, and based on McClelland's (1985) theory, the hypothesis was that the participant would infer that the leaders initiate international conflicts (a) in order to gain power, which corresponds to the need for power motive, (b) to gain popularity and prestige, which correspond to the need for achievement motive, and (c) to export democratic values abroad, which correspond to the need for affiliation motive. In other words, a three-factor structure should be evidenced. In addition, it was expected that the associations that will be found between the factors in this structure and the other measurements, would help to better understand the psychological meaning of the motive factors.

Method

Participants

64 females and 183 males living in the south of France were the participants. Their age ranged from 18 to 30 and the mean age was 21.30 (SD = 3.67). They were students from the various universities in Toulouse, France. All participants were unpaid.

Measures

Motives for War

The first questionnaire was the provisional Motives of Wars Questionnaire that was made of 65 items. These items were devised in multiple ways. First, a list of items was created by the investigators on the basis of the current literature on the causes of wars (e.g., Blainey, 1973; Bremer, 1980; Choucri & North, 1975; Diehl & Goertz, 1988; Kugler & Organski, 1989; Midlarsky, 1975, 1989, 2000; Singer & Small, 1972; Wright, 1942), and on the basis of the literature on human motivation (Apter, 2001; Deci & Ryan, 1985; McClelland, 1985). This list was then shown to six people who formed a focus group. These people suggested additional items based on their personal views. They also reformulated the items that were judged as ambiguous. The augmented list was presented to another group of people, and the process was repeated until no additional items were suggested. A large 14-point scale was printed following each item. The two extremes of the scales were labeled Disagree completely and Completely agree. Examples of items are shown in Table 1. The questionnaire was written in French.

Personality Dimensions

The second questionnaire was composed of 25 items taken from the International Pool of Items of Personality ([IPIP], Goldberg, 1999), five items for each personality factor (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroti-cism). A 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree was used.

Aggression

The third questionnaire was the Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992). It was composed of four scales measuring physical aggression (9 items, e.g., Once in a while, I can't control the urge to strike another person), verbal aggression (5 items, e.g., I often find myself disagreeing with people), anger (7 items, e.g., When frustrated, I let my irritation show) and hostility (8 items, e.g., I am sometimes eaten up with jealousy). Participants were asked to indicate, using a 5-point Likert scale, how much each statement was characteristic or uncharacteristic of them.

Social Dominance Orientation

The fourth questionnaire was the Social Dominance Orientation Questionnaire (Pratto, Sida-nius, Stallworth & Malle, 1994). The SDO scale tapped people's endorsement of inequality and hierarchical worldviews of societal groups. It comprised 16 items (e.g., 'Some groups of people are simply inferior to other groups'). Participants filled out a validated French version of the SDO questionnaire ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree (Duarte, Dambrun & Guimond, 2004).

Pro-War Questionnaire

The fifth questionnaire was the Anderson's version (Anderson, Benjamin, Wood & Bonacci, 2006) of the Velicer Attitudes Toward Violence Scale ([VATVS], Velicer, Huckel & Hansen, 1989). Only items belonging to Pro-War Attitude dimension were selected. This factor comprised 11 items (e.g., War is often necessary).

Rokeach Value Survey

The sixth questionnaire was a revised version (Braithwaite & Law, 1985) of the Rokeach Value Survey (Rokeach, 1973). Following Heaven, Organ, Supavadeeprasit and Leeson (2006), two scales were chosen: International Harmony and Equality, and National Strength and Order. The first scale comprised 8 items (e.g., Having all nations working together to help each other), the second comprised 4 items, (e.g., Being a united, strong, independent, and powerful nation). Participants were instructed to rate their level of agreement with the items on a 7-point scale ranged from 1 = "I reject this as a guiding principle in my life" to 7 = "I accept this as of the greatest importance as a guiding principle in my life".

Right Wing Authoritarianism

The seventh questionnaire was the French version of the Right Wing Authoritarism Questionnaire (Altemeyer, 1996) proposed by Dru (2007). It was composed of three scales measuring Authoritarian Aggression (e.g., Our country desperately needs a mighty leader who will do what has to be done to destroy the radical new ways and sinfulness that are ruining us), Authoritarian Submission (e.g., It is always better to trust the judgment of the proper authorities in government and religion than to listen to the noisy rabble-rousers in our society who are trying to create doubt in people's minds), and Conventionalism (e.g., The old-fashioned ways and old-fashioned values still show the best way to live.). Participants were instructed to indicate their responses on a 7-point rating scale ranging from Strongly agree to Strongly disagree. For each separate scale, alpha values computed on the sample have been indicated in Table 1.

Procedure

Each participant responded individually to the paper-and-pencil questionnaire in a quiet room at the university. The experimenters asked the participants to read the questionnaire's items and rate his/her degree of agreement with each statement. It took them approximately 60 minutes to complete the battery of seven questionnaires.

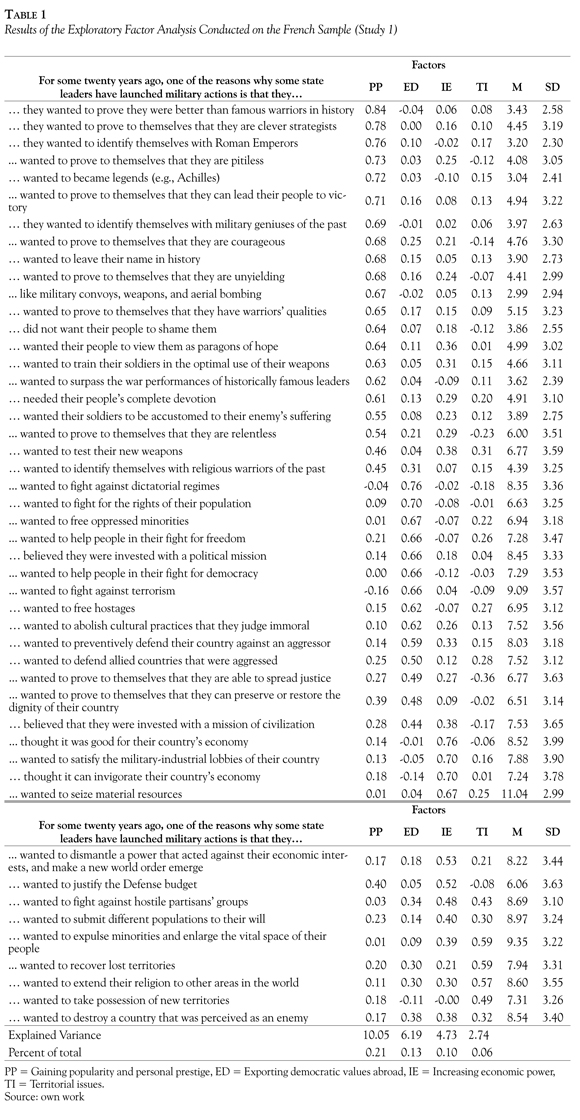

Results

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on the 65 items of the Motives of Wars Questionnaire. Based on the results of a first analysis, a second analysis was conducted on a subsample of 49 items, the ones for which the loadings were higher than 0.3 in the first analysis. Based on the scree test, a four-factor solution was retained. As we wanted to obtain factors independent from each other, a VARIMAX rotation was performed. Table 1 shows the main results of this second factor analysis. Eigenvalues ranged from 13.14 (first principal component) to 2.05 (fourth principal component). The eigenvalue of the fifth and sixth components were 1.48 and 1.33; that is, lower than 2. Correlations between factors ranged from -0.02 to 0.43 (median value = 0.21).

The first factor was labeled Gaining Popularity and Personal Prestige. It was loaded with items such as "From about twenty years ago, one of the reasons why some state leaders have launched military actions is that they wanted to prove that they were better warriors than famous warriors in history". The items that compose this dimension refer extensively to personal satisfaction and careerism concerns. The factor explained 21% of the variance. A score was computed by simply averaging the scores observed for four items with high loadings on this factor. The obtained score, 3.86 (SD = 2.37), was significantly lower (p < 0.001) than the midpoint of the agreement scale (see Table 3).

The second factor was labeled Exporting Democratic Values. It was loaded with items such as "From about twenty years ago, one of the reasons why some state leaders have launched military actions is that they wanted to help people in their fight for democracy". These items describe leaders who struggle against dictatorial regimes to promote the import of democratic and progressive way of governance. The factor explained 13% of the variance. The mean score, 7.92 (SD = 2.63), was close to the mid-point of the agreement scale.

The third factor was labeled Increasing Economic Power. It was loaded with items such as "From about twenty years ago, one of the reasons why some state leaders have launched military actions is that they thought it was good for their country's economy". It explained 10% of the variance. The mean score, 8.92 (SD = 2.67), was significantly higher than the midpoint of the agreement scale, (p < 0.001).

Finally, the fourth factor was labeled Territorial Issues. It was loaded with items such as "From about twenty years ago, one of the reasons why some state leaders have launched military actions is that they wanted to expulse minorities and enlarge the vital space of their people". It explained 6% of the variance. The mean score, 8.30 (SD = 2.33), was slightly higher than the mid-point of the agreement scale, (p < 0.02).

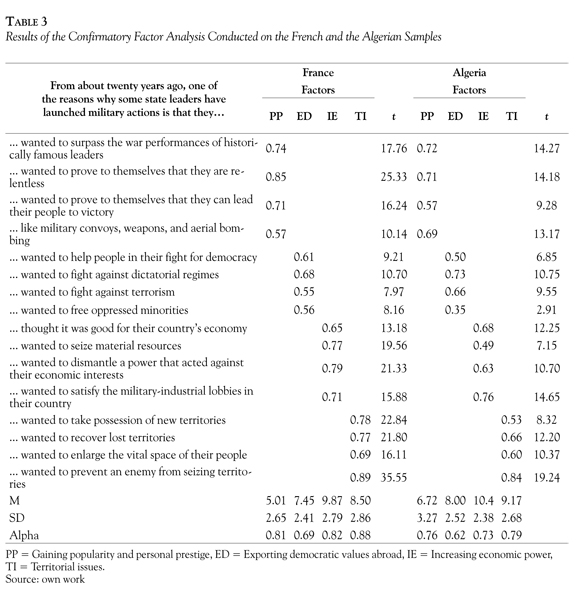

Table 2 shows the correlations between the four factor scores and the other measurements. Gaining personal prestige was significantly associated with hostility. The higher a participant's hostility score, the stronger this participant believes that one of the political leaders' motives was gaining personal prestige. Exporting democratic values was significantly correlated with pro-war attitudes, the valuation of national strength and order, authoritarian aggression and submission, and conventionalism. The higher a participant's scores on these factors, the stronger this participant believes that one of the political leaders' motives was the desire to export democratic values.

Increasing economic power is significantly correlated with agreeableness, with the valuation of international harmony and equality, with authoritarian aggression and submission, and with conventionalism. The higher a participant's agree-ableness score or international harmony score, the stronger this participant believes that one of the political leaders' motives was the desire to increase the economic power. The higher a participant's authoritarianism score, the weaker this participant believes that one of the political leader's motives was the desire to increase economic power. Finally, the territorial issues significantly correlate with the valuation of international harmony and equality, and with authoritarian submission. The higher participants scored on international harmony and equality questionnaire, the more they believe that one of the political leaders' motives was the desire to take over territories. In contrast, it also turned out that authoritarian submission approval seems to be slightly inversely related to the notion that the territorial expropriation is a core motive for war.

Discussion

Study 1 was aimed at analyzing people's views regarding the root motives that have led political leaders to launch military actions against other states. The hypothesis was that a three-factor structure of motives would be evidenced that comprises one factor related to the gaining of power, one factor related to the gaining of popularity and prestige, and one factor related to the exportation of democratic values abroad.

In fact, a slightly more complex structure was found, which comprised an additional factor that was related to territorial issues. The hypothesis can, nevertheless, be considered as well supported by the data: The additional factor appeared to be a factor that was related to the idea of an increase in power, and which complemented the increase of economic power factor. It has also been found that these two power motive factors are the ones that are most strongly endorsed by the participants, followed by the exportation of democratic values factor. The gaining popularity and personal prestige factor appeared to be much less endorsed than the other factors.

Study 1 was also aimed at examining the correlates of these factors, in terms of participants' personality, and participants' basic attitudes to war, aggression, and authoritarianism. The nice pattern of associations that has been found helped at uncovering the meaning of the motives factors. Participants who share authoritarian attitudes tended to consider the motives to go to war in a more positive light than the other participants. They tended to attribute nobler motives to political leaders than the other participants. In some way, they tend to "justify" the decisions of political leaders through the invocation of a noble objective: promoting democratic values. At the same time, they tend to dismiss the idea that political leaders go to war because they are moved by "egocentric" economic considerations. These finding are consistent with previous findings showing an association between right wing authoritarianism and positive attitudes to war (Cohrs & Moschner, 2002; Doty, Winter, Peterson & Kemmelmeier, 1997; McFarland, 2005; Pratto et al., 1994), and with previous findings that examined lay people's moral justification of the acceptance of war (Bandura, 1999; Jackson & Gaertner, 2010; Grussen-dorf, McAlister, Sandstrom, Udd & Morrison, 2002; McAlister, 2001).

In contrast, the participants who share anti-authoritarian attitudes tended to consider the motives to go to war in a more negative light than the other participants. In fact, they tended to "interpret" the decisions of the political leaders in the same way as scholars that work in the area of conflict studies; that is, promoting ones' state interests. At the same time, they tended to dismiss the idea that political leaders go to war because they are moved by "altruistic" democratic considerations.

In sum, Study 1 showed that, as expected, people have structured views about the motives for which political leaders decide to go to war. As also expected, these views appeared at least partly shaped by their personality, and in particular by the views they have regarding the role of authority in society or in the international arena.

Study 2

As previously stated, Study 2 was aimed at testing the robustness of the four-factor model that was evidenced in Study 1 — gaining popularity and personal prestige, exporting democratic values abroad, increasing the state's economic power, and territorial issues, using another sample of participants from France, and using confirmatory techniques. It was also aimed at testing the robustness of the relationships between each of the four factors and the various measurements that were used in Study 1. In particular, it was expected that participants holding authoritarian attitudes should view the motives of war as more altruistic in character (exporting democratic values abroad) and less egoistic in character (increasing the power of one's state) than participants holding opposite attitudes.

Method

Participants

79 females and 116 males living in the south of France were the participants. Their age ranged from 18 to 32 and the mean age was 25.38 (SD = 9.46). They were students from the various universities in Toulouse, France. As in Study 1, participants were unpaid.

Material and Procedure

The material consisted of six questionnaires. As in Study 1, these questionnaires were written in French. The first questionnaire was the Motives of Wars questionnaire that was made of 16 items, four items for each of the four factors that were identified in Study 1. These items are shown in Table 3. The second questionnaire was composed of the same 25 personality items that were taken from the International Pool of Items of Personality ([IPIP], Goldberg, 1999). The third questionnaire was the Social Dominance Orientation questionnaire that comprised 16 items. The fourth questionnaire was the Anderson's version of the Pro-War Attitude questionnaire (Anderson et al., 2006) that comprised 11 items. Because it has been cross-nationally validated we selected the Schwartz's instrument to measure human values in the following surveys. Then, the fifth instrument was the Portrait Values Questionnaire (Schwartz, 2006). It was composed of 40 short descriptions of people referring to value types. Each portrait measured one of the following values: Self-Direction (4 items, e.g., It is important to him to make his own decisions about what he does. He likes to be free to plan and to choose his activities for himself.), Power (3 items, e.g., It is important to her to be rich. She wants to have a lot of money and expensive things.), Universalism (6 items, e.g., He thinks it is important that every person in the world be treated equally. He wants justice for everybody, even for people he doesn't know.), Achievement (4 items, e.g., It is very important to her to show her abilities. She wants people to admire what she does.), Security (5 items, e.g., It is important to him to live in secure surroundings. He avoids anything that might endanger his safety.), Stimulation (3 items, e.g., She thinks it is important to do lots of different things in life. She always looks for new things to try), Conformity (4 items, e.g., He believes that people should do what they are told to do. He thinks people should follow rules at all times, even when no-one is watching.), Benevolence (4 items, e.g., It is very important to her to help the people around her. She wants to care for other people), Hedonism (3 items, e.g., He seeks every chance he can to have fun. It is important to him to do things that give him pleasure), and Tradition (4 items, e.g., Religious belief is important to her. She tries hard to do what her religion requires). Participants reported the degree of likeness between them and the fictitious person on 6-point response scales ranging from 1 = very dissimilar to 6 = very similar.

The sixth questionnaire was the Right Wing Authoritarianism questionnaire (Altemeyer, 1996). It was composed of three scales measuring authoritarian aggression, authoritarian submission, and conventionalism. For each separate scale, the alpha values computed on the sample that was indicated in Table 4. The procedure was the same as in Study 1.

Results and Discussion

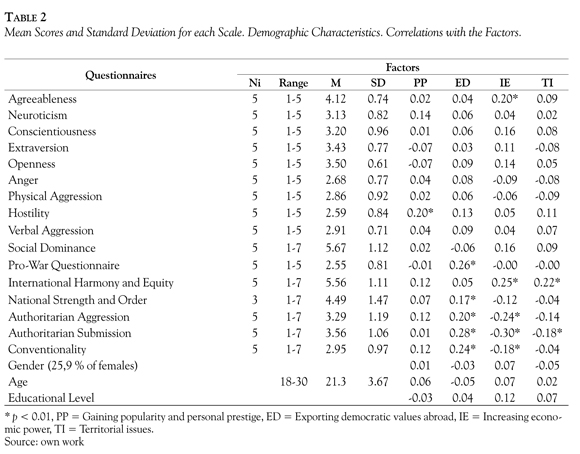

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the raw data. The model tested was the four-factor correlated model that is shown in Table 3. The values of the fit indices were 0.9 (GFI), 0.93 (CFI), 178.21 (χ2), 1.8 (x2/df), 0.06 [0.05-0.08] (RMSEA), and 0.08 (RMSR). All path coefficients were significant.

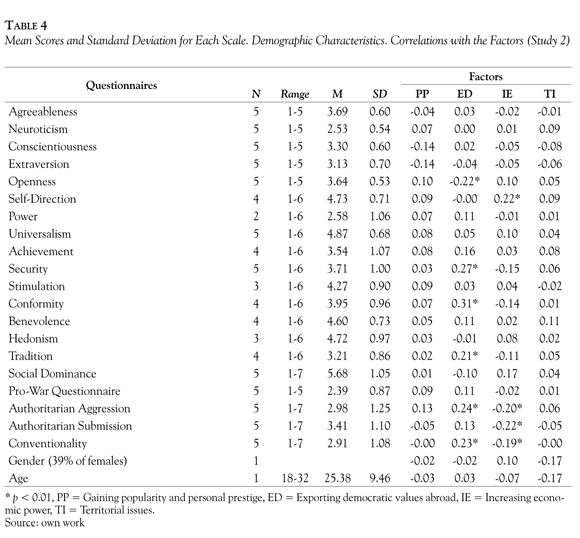

Table 4 shows the correlations between the four-factor structure and the other measurements. Exporting democratic values was significantly correlated with openness, security, conformity, tradition, authoritarian aggression, and conventionalism. The lower a participant's scores on openness, the stronger this participant believes that one of the political leaders' motives was the desire to export democratic values. The higher a participant's scores on the other factors, the stronger this participant believes that one of the political leaders' motives was the desire to export democratic values. Increasing economic power is significantly correlated with self-direction, authoritarian aggression and submission, and with conventionalism. The higher a participant's self-direction score, the stronger this participant believes that one of the political leaders' motives was the desire to increase economic power. (Self-direction was the only value of the openness to change superordinate dimension that exhibited a significant correlation). The higher the participant's authoritarianism score, the weaker this participant believes that one of the political leaders' motives was the desire to increase economic power.

In sum, the four-factor model that was evidenced in Study 1 — gaining popularity and personal prestige, exporting democratic values abroad, increasing the state's economic power, and territorial issues — was found to satisfactorily fit new data from another sample of participants. In addition, the most important relationships evidenced in Study 1 between each of the four factors and the various measurements were also found: Authoritarian/conformist attitudes strongly predict the way people "interpret" political leaders' motives. People that hold authoritarian/conformist attitudes tend to ennoble these motives, whereas people with opposite attitudes tend to see them more or less in the same light as political scientists, who tend to emphasize power motives over educational motives. The introduction of the portrait values questionnaire allowed a better understanding of the four factor model. The readiness to view the war as a way of promoting progressive type of governance was positively associated with conservative values. This finding is consistent with previous ones showing a connection between militaristic attitudes and conservative values (Bégue & Apostolidis, 2000; Mayton, Peters & Owens, 1999). The fact that self-direction was positively correlated with a power motive (war as negative), was consistent with findings that related self-direction to antinuclear activism (Mayton & Furnham, 1994).

Study 3

As Study 2, Study 3 was aimed at testing, using confirmatory techniques, the robustness of the four-factor model — gaining popularity and personal prestige, exporting democratic values abroad, increasing the state's economic power, and territorial issues, on a new sample of participants, but, this time, on a sample of participants who were older and culturally different from the participants within Studies 1 and 2: A sample of adult participants living in the Maghreb. In other words, Study 3 was aimed at testing the cross-age and cross-cultural robustness of the four-factor model.

Study 3 was also aimed at re-examining the relationships between each of the four factors and the various measurements that were used in Study 2. It was expected that, among Maghrebi participants, traditional/authoritarian attitudes should lead participants to view the motives of war in a completely different light as the one that was found among the Western European participants.

Maghrebi people (Algeria) in particular, and possibly the Arabs in general, tend to view themselves as the victims of most of the wars that have been launched during the recent decades. Nowadays, the Algerian self-representation is mainly defined in reference to the long war of independence (Stora, 2003, p. 15). The collective remembering symbolized by both cult of heroes and national trauma is promoted by the FLN The Algerian political culture is marked by the dominance of these elites claiming their ruling legitimacy on the grounds of "revolutionary credentials" (McQueen, 2009, p. 94). Algeria is a country in which power is highly centralized. In addition, owing to the threat of Islamic terrorist movements, the level of militarization of Algeria is high. After the colonial war, Algeria strove to live up more thoroughly to their traditional values as a way of rejecting the European hegemony (Bourdieu, 1998). As a result, it is unlikely that the more traditional people among them, the ones that are most opposed to Western influence, view the political leaders' motives in a positive light. Rather, they should view these motives in a more negative light than people with less traditional views; that is, they should see these motives as more "egoistic" in character (increasing economic power) and as less "altruistic" in character (exporting democratic values) than the participants holding less traditional/authoritarian views.

Method

Participants

Algerian participants agreed to participate without financial compensation. All participants were recruited within the town of Annaba; they completed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire. The participants were all Arab speakers and were therefore familiar with modern written Arabic into which the material has been translated. Most of the participants were students (N = 130), including undergraduates and postgraduates. There was also various professionals, individuals from associations. The sample comprised 180 participants ranged from 18 to 60 years (M = 32.50, SD = 11.52, 104 women, 69 men and 7 people who did not report any demographic information).

Material and Procedure

The material consisted of the same first six questionnaires used in Study 2. The sixth questionnaire was the Zakrisson's (2005) version of the Right Wing Authoritarism questionnaire. As the original version, it was composed of three scales measuring Authoritarian Aggression (e.g., If the society so wants, it is the duty of every true citizen to help to eliminate the evil that poisons our country from within.), Authoritarian Submission (e.g., Our country needs a powerful leader, in order to destroy the radical and immoral currents prevailing in society today.), and Conventionalism (e.g., It would be best if newspapers were censored so that people would not be able to get hold of destructive and disgusting material). This questionnaire was chosen because it was shorter and also because it seemed easier to administer to the Maghrebi sample than the original version. Indeed, the Zakrisson's version of the questionnaire comprised shortened and simplified items. Moreover, it excludes items referring explicitly to sexuality; by doing that, we avoided the risk of offending the Algerian's religious susceptibility.

These questionnaires were written in Arabic. In designing the Arabic version of the items, guidelines proposed in the literature on cross-cultural methodology were followed as closely as possible (e.g., independent, blind back-translations, educated translation, small-scale pretests). Also, one of the authors was fluent both in English, in Arabic and in French, and was able to detect any inconsistencies in the material. As wars and conflicts have the same basic meaning in both contexts, it was relatively easy to find equivalent terms.

Results

A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the raw data. The model tested was the four-factor correlated model that is shown in Table 3. The values of the fit indices were 0.89 (GFI), 0.87 (CFI), 194.21 (χ2), 1.85 ^/df), 0.07 [0.06-0.09] (RMSEA), and 0.08 (RMSR). All path coefficients were significant.

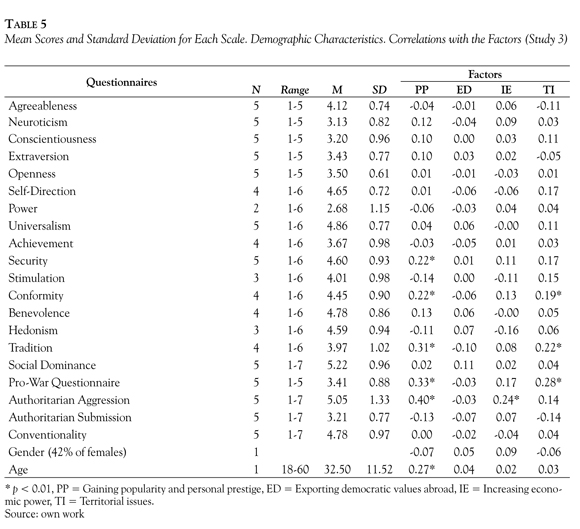

Table 5 shows the correlations between the four-factor structure and the other measurements. Gaining popularity and personal prestige was significantly correlated with security, conformity, tradition, pro-war attitudes, and authoritarian aggression. The higher a participant's scores on these factors, the stronger this participant believed that one of the political leaders' motives was the desire to gain popularity and personal prestige. Increasing the economic power is significantly correlated with authoritarian aggression. The higher a participant's authoritarianism score, the higher this participant believed that one of the leaders' motives was the desire to increase economic power. Territorial issues are significantly correlated with conformity, tradition, and pro-war attitudes. The higher a participant's scores on these factors, the stronger this participant believed that one of the political leaders' motives was the desire to gain or to "clean" territory.

Comparing the Algerian and French Data

A series of covariance analysis were also conducted with the various motives to go to war scores as the criteria, country as the predictor, and gender and age as the covariates. The Maghrebi's gaining popularity and personal prestige score (M = 6.72) was significantly higher than the corresponding French score (M = 5.01), F(1, 371) = 19.21, p < 0.001.

Another series of covariance analysis were conducted with the scores shown in Table 4 and 5 as the criteria, country as the predictor, and gender and age as the covariates. The Maghrebi's mean security score (M = 4.59) was significantly higher than the French one (M = 3.72), F(1, 340) = 48.16, p < 0.001. The Maghrebi's conformity score (M = 4.43) was significantly higher than the French one (M = 3.94), F(1, 338) =15.53, p < 0.001. The Maghrebi's tradition score ( M = 3.96) was significantly higher than the French one ( M = 3.21), F(1, 339) = 34.30, p < 0.001. Finally, the French's social dominance score (M = 5.68) was significantly higher than the Maghrebi's score ( M = 5.22), F(1, 335) = 11.37, p < 0.001.

Discussion

The model that was evidenced in Study 1 was found to satisfactorily fit the data from the sample of Maghrebi participants. In addition, the mean scores were similar, except for the gaining of popularity and personal prestige factor that was higher among the Maghrebi participants. This difference may be explained by the fact that the Algerians tend, for historical reasons, to perceive political power as a more personal issue than French people.

As expected, the relationship between traditional/ authoritarian attitudes and the various motives of wars were reversed as compared with what was observed in Studies 1 and 2. The stronger relationships were found in the gaining popularity and personal prestige factor, and among the territorial issues factor. Among Maghrebi participants, traditional/authoritarian attitudes were more strongly endorsed than among French participants. These attitudes led the Maghrebi participants to view the motives of war as clearly associated with egoistic preoccupations and with imperialistic concerns from the part of the leaders. In other words, traditional/authoritarian attitudes were, as expected, associated with the perception of the motives of war in a very negative light.

General Discussion

The present set of studies examined the way people from two very different countries perceive the motives that lead political leaders to launch armed actions against other states. Based on McClelland's (1985) theory of human motivation, three types of possible perceived motives were considered: motives associated with the state's power (e.g., increasing the country's economic power), motives associated with the other states' political character (e.g., whether neighboring states are relatively peaceful democracies or dangerous autocracies), and motives associated with domestic issues (e.g., appearing as a strong leader able to efficiently fight for the security of the country). Certain factors that have been found for the questionnaire of motives are strikingly similar to those observed in a study conducted by Stagner (1942) during World War II, which found that people believe that wars are caused by economic rivalries, national imperialism, munitions makers, and political leaders desiring power.

Analyses of the data gathered from these two countries showed that this model holds, with the condition that the increasing power perceived motive is divided into two separate motives: one associated with the economy and one associated with the territory. Indisputably, people have structured conceptions of the motives that lead leaders to launch armed action against other states (otherwise no factor could have been evidenced), and the motives people invoke are different and form a richer set than the "objective" set of motives that is suggested by political scholars.

Understandably, people's views are partly shaped by their political environment and by their attitudes towards conflicts. First, the motives of war tend to be seen as more personal and as more associated with domestic issues among people living in a country that is not wholly democratic yet (Algeria) than among people living in an old (although far from perfect) democracy (France). Secondly, among traditional/authoritarian people living in a rich, developed country (that would be able to successfully face others' aggressions), the motives of war tend to be seen in a more positive light than among liberal people living in this country. However, among traditional/authoritarian people living in a relatively poor, developing country (that could be the victim of others' aggressions), and the motives of war tend to be seen in a more negative light than among liberal people living in this country.

This complex set of findings supports the usefulness of the four-factor model of motives. Considering only the French data, it could have been argued that the only two factors that matter are increasing the economic power and exporting democracy. The territorial issue factor could have been considered as a twin for the economic power factor, and the gaining popularity factor could have been considered as not important, owing to its low endorsement by people. The Algerian data, however, show that these two factors are important and can play a strong role. This is probably because, in not-fully democratic states, personal power is, as already stated, a salient reality. This is also because, in geographic areas where borders are not already well established, the territorial issues keep being salient ones.

Future studies should test whether the model of psychological motives that has been suggested in the present set of studies also hold in other African and Asiatic countries. Future studies should also explore the way this model can be extended; that is, whether additional factors are needed. Finally, the four-factor structure could be used as a convenient tool to capture, in a very synthetic way, the way people from different countries and cultures interpret the leaders' motives behind such armed actions as the Iran-Iraq war, the India-Pakistan conflicts, the invasion of Kuwait, or the recent intervention in Afghanistan by allied forces, to only quote a few, and the evolution of this perception as time elapses.

References

Altemeyer, R. A. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Links ]

Anderson, C. A., Benjamin, A. J., Wood, P. K. & Bonacci, A. M. (2006). Development and testing of the Attitudes Toward Violence Scale: Evidence for a four-factor model. Aggressive Behavior, 32(2), 122-136. [ Links ]

Apter, M. J. (2001). Motivational styles in everyday life: A guide to Reversal Theory. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193-209. [ Links ]

Bégue, L. & Apostolidis, T. (2000). The 1999 Balkans war: Changes in ratings of values and prowar attitudes among French students. Psychological Reports, 86(3), 1127-1133. [ Links ]

Blainey, G. (1973). The causes of war. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Bourdieu, P. (1998). La domination masculine. Paris: Seuil. [ Links ]

Braithwaite, V. A. & Law, H. G. (1985). Structure of human values: Testing the adequacy of the Rokeach Value Survey. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(1), 250-263. [ Links ]

Bremer, S. A. (1980). National capabilities and war proneness. In J. D. Singer (Ed.), The correlate of war project II: Testing some realpolitiks models (pp. 57-82). New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Bueno de Mesquita, B. (1981). The war trap. New Haven/ London: Yale University Press. [ Links ]

Buss, A. H. & Perry, M. P. (1992). The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 452-459. [ Links ]

Chan, S. (1984). Mirror, mirror on the wall... Are the freer countries more pacific? Journal of Conflict Resolution, 28(4), 617-648. [ Links ]

Choucri, N. & North, R. C. (1975). Nations in conflict: National growth and industrial violence. San Francisco: Freeman. [ Links ]

Choucri, N. & North, R. C. (1989). Lateral pressure in international relations: Concept and theory. In M. I. Midlarsky (Ed.), Handbook of war studies (pp. 289-326). Boston, MS: Unwin-Hyman. [ Links ]

Chittick, W. O. & Freyberg-Inan, A. (2001). Foreign policy opinions on the use of force. In P. P. Everts & P. Isernia (Eds.), Public opinion and the international use of force (pp. 31-56). London: Routledge. [ Links ]

Cohrs, J. C. & Moschner, B. (2002). Antiwar knowledge and generalized political attitudes as determinants of attitude toward the Kosovo War. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 8(2), 139-155. [ Links ]

Cohrs, J. C., Moschner, B., Maes, J. & Kielmann, S. (2005a). Personal values and attitudes toward war. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 11(3), 293-312. [ Links ]

Cohrs, J. C., Moschner, B., Maes, J. & Kielmann, S. (2005b). The motivational bases of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation: Relations to values and attitudes in the aftermath of September 11, 2001. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(10), 1425-1434. [ Links ]

Cottam, R. W. (1977). Foreign policy motivation: A general theory and a case study. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. [ Links ]

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. New York: Plenum. [ Links ]

Diehl, P. F. & Goertz, G. (1988). Territorial changes and militarized conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 32(1), 103-122. [ Links ]

Dixon, W. J. (1994). Democracy and the management of international conflict. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 37(1), 42-68. [ Links ]

Doty, R. M., Winter, D. G., Peterson, B. E. & Kemmelmeier, M. (1997). Authoritarianism and American students' attitudes about the Gulf War, 1990-1996. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(11), 1133-1143. [ Links ]

Dru, V. (2007). Authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and prejudice: Effects of various self-categorization conditions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(6), 877-883. [ Links ]

Duarte, S., Dambrun, M. & Guimond, S. (2004). La dominance sociale et les «mythes légitimateurs»: Validation frangaise de l'échelle d'Orientation á la Dominance Sociale. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale/International Review of Social Psychology, 17(4), 97-126. [ Links ]

Goldberg, L. R. (1999). A broad-bandwidth, public domain, personality inventory measuring the lower-level facets of several five-factor models. In I. Mervielde, I. Deary, F. DeFruyt & F. Ostendorf (Eds.), Personality psychology in Europe (pp. 7-28). Tilburg Netherland: Tilburg University Press. [ Links ]

Grussendorf, J., McAlister, A. L., Sandstrom, P., Udd, L. & Morrison, T. C. (2002). Resisting moral disengagement in support for war: Use of the "Peace Test" scale among student groups in 21 nations. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 8(1), 73-83. [ Links ]

Heaven, P. C. L., Organ, L. A, Supavadeeprasit, S. & Leeson, P. (2006). War and prejudice: A study of social values, right-wing authoritarianism, and social dominance orientation. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(3), 599-608. [ Links ]

Herrmann, R. K., Tetlock, P. E. & Visser, P. S. (1999). Mass public decisions to go to war: A cognitive-interactionist framework. American Political Science Review, 93(3), 553-573. [ Links ]

Heskin, K. & Power, V. (1994). The determinants of Australians' attitudes toward the Gulf war. Journal of Social Psychology, 134(3), 317-330. [ Links ]

Hewitt, J. J. & Young, G. (2001). Assessing the statistical rarity of wars between democracies. International Interactions, 27(3), 327-351. [ Links ]

Jackson, L. E. & Gaertner, L. (2010). Mechanisms of moral disengagement and their differential use by right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation in support of war. Aggressive Behavior, 36(4), 238-250. [ Links ]

Kugler, J. & Organsky, A. F. K. (1989). The power transition: A retrospective and prospective evaluation. In M. I. Midlarsky (Ed.), Handbook of war studies (Vol. 1, pp. 172-194). Winchester: Unwin Hyman. [ Links ]

López-López, W. & Sabucedo, J. M. (2007). Culture of peace and mass media. European Psychologist, 12(2), 147-155. [ Links ]

Mayton, D. M. & Furnham, A. (1994). Value underpinnings of antinuclear political activism: A cross-national study. Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 117-128. [ Links ]

Mayton, D. M., Peters, D. J. & Owens, R. W. (1999). Values, militarism, and nonviolent predispositions. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 5(1), 69-77. [ Links ]

McAlister, A. (2001). Moral disengagement: Measurement and modification. Journal of Peace Research, 38(1), 87-99. [ Links ]

McClelland, D. C. (1985). Human motivation. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman and Company. [ Links ]

McFarland, S. G. (2005). On the eve of war: Authoritarianism, social dominance, and American students' attitudes toward attacking Iraq. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31 (3), 360-367. [ Links ]

McQueen, B. (2009). Political culture and conflict resolution in the Arab World Lebanon and Algeria. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing Limited. [ Links ]

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2001). The tragedy of great power politics. New York: Norton. [ Links ]

Midlarsky, M. I. (1975). On war. New York: Free Press. [ Links ]

Midlarsky, M. I. (1989). Handbook of war studies (Vol. 1). Winchester: Unwin Hyman. [ Links ]

Midlarsky, M. I. (2000). Handbook of war studies (Vol. 2). Chicago: The University of Michigan Press. [ Links ]

Moerk, E. L. & Pincus, F. (2000). How to make wars acceptable. Peace & Change, 25(1), 1-22. [ Links ]

Morgan, T. C. & Schwebach, V. L. (1992). Take two democracies and call me in the morning: A prescription for peace? International Interactions, 17(4), 305-320. [ Links ]

Most, B. A. & Starr, H. (1989). Inquiry, logic and international politics. Columbia, SC: University ofSouth California Press. [ Links ]

Nelson, L. L. & Milburn, T. W. (1999). Relationships between problem-solving competencies and militaristic attitudes: Implications for peace education. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 5(2), 149-168. [ Links ]

Peterson, B. E., Winter, D. G. & Doty, R. M. (1994). Laboratory tests of a motivational-perceptual model of conflict escalation. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 38(4), 719-748. [ Links ]

Prager, C. A. L. (2003). Aspects of judging and understanding massive human right abuses. In C. A. L. Prager & T. Govier (Eds.), Dilemmas of reconciliation (pp. 197-219). Waterloo, ON: Wilfried Laurier University Press. [ Links ]

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M. & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741-763. [ Links ]

Rokeach, M. (1973). The Nature of Human Values. New York: Free Press [ Links ]

Schwartz, S. H. (2006). Value orientations: Measurement, antecedents and consequences across nations. In R. Jowell, C. Roberts, R. Fitzgerald & G. Eva (Eds.), Measuring attitudes cross-nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey (pp. 169203). London: Sage. [ Links ]

Sidanius, J. & Liu, J. H. (1992). The Gulf War and the Rodney King beating: Implications of the general conservatism and social dominance perspectives. Journal of Social Psychology, 132(6), 685-700. [ Links ]

Singer, J. D. & Small, M. (1972). The wages of war, 18161965: A statistical handbook. New York: John Wiley. [ Links ]

Sobek, D., Abouharb, R. A. & Ingram, C. G. (2006). The Human Rights peace: How the respect for Human Rights at home leads to peace abroad. Journal of Politics, 68(3), 519-529. [ Links ]

Stagner, R. (1942). Some factors related to attitude toward war, 1938. The Journal of Social Psychology, 16, 131-142. [ Links ]

Stora, B. (2003). Algeria/Morocco: The passion of the past. Representation of the nation that unite and divide. Journal of North African Studies, 8(1), 14-34. [ Links ]

Velicer, W. F., Huckel, L. H. & Hansen, C. E. (1989). A measurement model for measuring attitudes toward violence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15(3), 349-364. [ Links ]

Waltz, K. N. (1979). Theory of international politics. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

Winter, D. G. (1993). Power, affiliation and war: Three tests of a motivational model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(3), 532-545. [ Links ]

Winter, D. G. (2007). The role of motivation, responsibility, and integrative complexity in crisis escalation: Comparative studies of war and peace crises. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 920-937. [ Links ]

Wolfers, A. (1962). The goals offoreign policy. In Discord and collaboration: Essays on international politics (pp. 67-80). Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins Press. [ Links ]

Wright, Q. (1942). A study of war. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Zakrisson, I. (2005). Construction of a short version of the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(5), 863-872. [ Links ]