Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Universitas Psychologica

versión impresa ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.12 no.2 Bogotá may./agos. 2013

Explaining Emotional Labor's Relationships with Emotional Exhaustion and Life Satisfaction: Moderating Role of Perceived Autonomy

Explicando las relaciones de labor emocional con exhaustividad emocional y satisfacción de vida: moderando el papel de la autonomía percibida

Neena Gopalan *

University of Central Missouri, United States

Satoris S. Culbertson **

Kansas State University, United States

Pedro Ignacio Leiva ***

Universidad de Chile, Chile

* University of Central Missouri, United States. Department of Psychological Sciences. E-mail: gopalan@ucmo.edu

** Kansas State University, United States. Department of Psychology. E-mail: satoris@ksu.edu

*** Universidad de Chile, Chile. Faculty of Economics and Business. E-mail: pleivan@unegocios.cl

Recibido: enero 6 de 2012 | Revisado: agosto 2 de 2012 | Aceptado: agosto 19 de 2012

Para citar este artículo:

Gopalan, N., Culbertson, S. & Leiva, P. I. (2013). Explaining emotional labor's relationships with emotional exhaustion and life satisfaction: Moderating role of perceived autonomy. Universitas Psychologica, 12(2), 347-356.

Abstract

This study assessed the extent to which two kinds of emotional labor (surface and deep acting) can lead to emotional exhaustion, reducing one's overall life satisfaction. Based on Self-Determination theory, the importance of perceived autonomy was also studied in relation to how it moderates the relationship between emotional labor and emotional exhaustion. Data collected online from 241 staff employed at a university in central United States revealed that the relationship between surface acting and emotional exhaustion was stronger among people with lower perception of autonomy, which had an impact on overall life satisfaction. No significant relationship between deep acting and emotional exhaustion was found. Future directions should include studying the model on other samples and using a longitudinal design.

Key words authors: Emotional Labor, Emotional Exhaustion, Life Satisfaction, United States.

Key words plus: Perceived Autonomy, Quantitative Research.

Resumen

Este estudio evaluó el grado en el cual dos clases de labores emocionales (acción profunda y superficial) pueden conducir a la exhaustividad emocional, reduciendo en general la satisfacción de vida. Basados en la teoría de la Auto-Determinación, la importancia de la autonomía percibida puede ser estudiada en relación a cómo es moderada la relación entre labor emocional y exhaustividad emocional. Los datos se recogieron via web desde 241 empleados en una universidad en la zona centro de Estados Unidos y revelaron que la relación entre acción superficial y exhaustividad emocional fue más fuente entre personas con bajos niveles de percepción de autonomía, la cual podría tener un impacto sobre la satisfacción de vida. No se encontraron relaciones significativas entre las acciones profundas y la exhaustividad emocional. Futuras investigaciones deberían incluir en el estudio del modelo utilizar otras muestras y utilizar un diseño longitudinal.

Palabras clave autores: Labor emocional, exhaustividad emocional, satisfacción de vida, Estados Unidos.

Palabras clave adicionales: Autonomía percibida, investigación cuantitativa.

doi:10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY12-2.eelr

In many occupations, the display of certain emotions is required. For example, it is expected that restaurant servers smile at customers, that nurses be kind and caring, and judges appear emotionless. In all these cases, certain emotional expression (or, in some cases, emotional suppression) is anticipated for effective workplace interaction. This regulation of one's emotional expressions is termed as emotional labor (Grandey, Fisk, Mattila, Jansen & Sideman, 2005; Martínez, 2001). Hochschild (1983) defined emotional labor as "the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display" (p. 7). Emotional display rules involve the management, or regulations, of one's emotions through surface acting or deep acting (Brotheridge, 2006; Morris & Feldman, 1996). In surface acting, one regulates his or her emotional expressions and fakes them. In deep acting, one tries to change his or her cognitive processes to actually feel the emotions required (Grandey, 2000).

Emotional labor has been linked to positive outcomes for individuals (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002) because feelings of satisfaction, pride, and security may also increase when individuals engage more in their jobs (Rafael & Sutton, 1987). Unfortunately, the research has revealed that there are also negative effects of emotional labor. For example, Hochschild (1983) warned that managing one's feelings to create a publicly observable facial and physical display could be emotionally laborious. Emotional labor can result in burnout (Schaubroeck & Jones, 2000), especially leading to emotional exhaustion (Kalbers & Fogarty, 2005; Melamed, Shirom, Toker & Shapira, 2006), which closely resembles fatigue, job-related depression, psychosomatic complaints, and anxiety (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner & Schaufeli, 2001).

It is clear that the emotional labor can have both positive and negative outcomes. It remains unclear, however, when emotional labor will lead to beneficial consequences or when individuals will suffer from emotional labor's deleterious effects. In the current study, we focus on life satisfaction (Diener, Emmons, Larsen & Griffin, 1985; Moyano, Flores & Soromaa, 2011) as a potential positive outcome and emotional exhaustion (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002; Gil-Monte & Peiró, 1999; Gil-Monte & Zuñiga-Caballero, 2010; Quintana, 2005) as a potential negative outcome of emotional labor. Based on Ryan and Deci's (2002) Self-Determination Theory, we examine the interaction between emotional labor in one's job and the perceived autonomy that an individual perceives he or she has in the engagement of emotional labor on the proximal prediction of emotional exhaustion and on the distal prediction of life satisfaction.

Rationale of the Study

It remains unclear under what circumstances the emotional labor is likely to lead to a positive outcome, such as life satisfaction. We propose that the relationship between emotional labor and life satisfaction is likely a distal relationship, explained by the emotional exhaustion experienced by the individual engaging in the emotional labor. For example, researchers have suggested that one reason in which the emotional labor may positively impact the employee mental well-being, may possibly be because of the feelings of satisfaction, pride, and security that may also increase when they engage more in their jobs (Brotheridge & Grandey, 2002). Thus, the relationship between emotional labor and mental well being may be influenced by emotions (in this case, satisfaction, pride and security) that individuals feel. If individuals do not feel these emotions, or are emotionally exhausted, they may not experience the enhanced mental well being. Thus, although researchers (e.g., Grandey, 2000) have suggested that displaying emotions may actually create those emotions, it could be argued that happiness would not result if such emotions were not actually created. Finally, Zammuner, Lotto, and Galli (2003) noted that one's quality of life is related to absence of negative feelings. An individual who is emotionally exhausted would be less likely to report high levels of life satisfaction. This negative impact that emotional exhaustion has on life satisfaction has been reported in previous research (Demerouti et al., 2001). Based on all the above logic, we argue that the emotional exhaustion exerts an indirect effect on the relationship between the emotional labor and life satisfaction.

The question, then, becomes: When do individuals experience emotional exhaustion from engaging in emotional labor? We propose that the emotional exhaustion that individuals experience from emotional labor depends, in part, on whether the labor occurs as surface or deep acting, and in the level of autonomy that individuals perceive they have in the engagement of emotional labor. We propose two models in this study. In one model, we introduce the surface acting as the variable treatment hypothesized to result in lower life satisfaction through emotional exhaustion. Using the same logic, we introduce a second model where deep acting is the independent variable hypothesized to bring about reduced life satisfaction through emotional exhaustion.

Perceived Autonomy in Engagement of Emotional Labor

Another factor that may determine the level of emotional exhaustion that one experiences from emotional labor is the level of perceived autonomy that an individual has in his or her engagement of emotional labor. The importance of perceived autonomy can be explained by Ryan and Deci's (2002) Self-Determination Theory (SDT), according to which autonomy is a sense of willingness and volition to engage in a certain behavior. It refers to an individual's active participation in determining his or her own behavior or that one's behavior is self-determined. In the current study, autonomy is reflected in whether an individual feels the need to express organizationally mandated emotions (i.e., engage in emotional labor). To the extent that an employee perceives the expression (or suppression) of emotions as a requirement mandated by the organization, he or she lacks of autonomy, as the behavior is not engaged in upon one's own accord. The importance of autonomy, as conceptualized by SDT, has been linked to numerous positive outcomes, including bringing about long-term healthy behavior change (Jacobs & Claes, 2008), improving the student motivation in educational settings (Reeve, 2002), and predicting the employee performance and satisfaction (Gagné & Deci, 2005).

Based on SDT, we propose that the relationships between emotional labor (surface acting and deep acting) and emotional exhaustion are moderated by the level of autonomy that the individuals perceive they have in the expression of emotional labor in their jobs. That is, the research has shown that emotional labor can result in employees experiencing emotional exhaustion (Ashforth, Tomiuk & Kulik, 2008). However, we argue that this relationship is influenced by whether employees perceive they have autonomy in deciding to engage in emotional labor. If employees feel that they are engaging in emotional labor due to their own volition, we propose they will experience a sense of autonomy and be less emotionally exhausted. Conversely, if employees perceive they have little or no autonomy for engaging in emotional labor, they will be more emotionally exhausted.

Summary and Analytic Strategy

In sum, we propose that the relationship between emotional labor and life satisfaction is mediated by emotional exhaustion. In addition, the relationship between emotional labor and emotional exhaustion is influenced by the level of the perceived autonomy that the individual has in the expression of emotional labor. As noted earlier, we examined this model using surface acting as the form of emotional labor in one set of analyses (Model 1) and deep acting as the form of emotional labor in another set of analyses (Model 2).

The models being tested are examples of a mediated relationship that is moderated by another variable along the paths. We used moderated mediation analysis in this research, which helps to explain both how and when a given effect can occur (Preacher, Rucker & Hayes, 2007). This technique tests whether an indirect effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable through a mediator variable depends on the value of a moderator variable. A moderated mediation occurs if the indirect process, responsible for producing the treatment effect on an outcome, tends to depend on the moderator value. For this study, a moderated mediation will be said to exist if the effect of emotional labor (the independent variable) on life satisfaction (the dependent variable) through emotional exhaustion (the mediator) depends on levels of autonomy (the moderator).

Method

Participants and Procedure

Data for this study were collected online by forwarding a link to an online survey to approximately 1000 full-time classified staff employed at a medium-sized university in the central United States. These include employees holding positions such as administrative assistants, accountants, librarians, office managers, food service staff, supervisors, and office support staff. Being of service to students and faculty and visitors, these staff members interact with a variety of individuals on a regular basis.

The final response rate was 241 (24%). Of these, 17% were males and remaining 83% were females. The participant's age varied between 21 and 68 years (M = 46, SD = 10.79). A total of 91% of the respondents were Caucasian, 2% were Hispanic, 1% was African-American, and the remaining 3% identified themselves as 'others.'

Measures

Emotional labor

Surface Acting and Deep Acting were measured using Brotheridge and Lee's (1998) scale. Three items measured surface acting (sample item: "On an average day at work, how often do you have to resist expressing your true feelings?"; α = 0.79) while three items measured deep acting (sample item: "On an average day at work, how often do you have to actually experience the emotions that you must show?"; α = 0.87). Responses were given on a scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = always.

Perceived Autonomy in Engagement

of Emotional Labor

A 7-item job-focused emotional labor scale (Best, Downey & Jones, 1997) was used in order to measure the extent to which employees perceived autonomy in their engagement of emotional labor. This scale measures one's perceptions regarding the autonomy that he or she has to display positive emotions and to hide negative emotions. Only three items were retained because of the results of a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) assessing the study's measurement model (reported in the Results section). Individuals were asked, "On an average day at work, how frequently do you perform the following?" with specific retained items being, "Hiding your anger or disapproval over something someone had done (i.e., an act that is distasteful to you)," "Hiding your disgust over something someone had done," and "Expressing feelings of sympathy (e.g., saying you "understand" or "sorry" to hear about something)." Response options ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (always required). Because higher values indicate emotional labor is seen as being required to a greater extent, the scores were reversed for higher scores to indicate greater perceived autonomy. Coefficient alpha for this scale was 0.8.

Emotional Exhaustion

It was measured using five items taken from the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach, 1982). However, due to the results of the CFA (see Results section), two items were deleted. The three items retained were, "I feel emotionally drained from work," "I feel tired when I get up in the morning and have to face another day of work," and "I feel burned out from my work." Response choices ranged from 1 (a few times a year) to 6 (everyday). Coefficient alpha for this 3-item scale was 0.87.

Life Satisfaction

Five items from Diener's (1985) General Life Satisfaction scale were used to measure life satisfaction. Based on a CFA (see Results section), one item was dropped from the scale. The remaining four items retained were, "In most ways, my life is close to my ideal," "The conditions of my life are excellent," "I am satisfied with life," and "If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing." Response choices ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Coefficient alpha for this scale was 0.92.

Results

Measurement Model Assessment

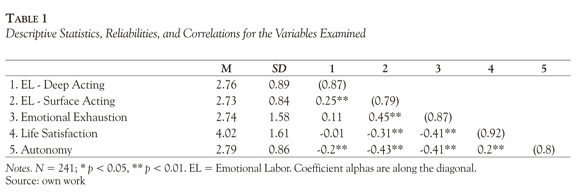

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) performed with all the items to assess the study's measurement model showed a lack of fit for the five-factor hypothesized model (X2 (220) = 583.58, p < 0.001, goodness-of-fit index [GFI] = 0.82, comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.94, non-normed fit index [NNFI] = 0.93, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.08), due to correlation among the errors of four the perceived autonomy scale items, and double loading of two emotional exhaustion scale items and one life satisfaction scale item. After deleting these six items, a five-factor CFA performed showed excellent goodness-of-fit (X2 (94) = 114.87, p > 0.05, GFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.99, NNFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.03). A one-factor CFA showed that the hypothesized five-factor solution was significantly better (X2 (104) = 1717.87, p > 0.01, GFI = 0.53, CFI = 0.49, NNFI = 0.42, RMSEA = 0.23; Δχ2 (10) = 1603.00, p < 0.001). The Cronbach alpha indexes suggest that the five scales were reliable. Finally, a five-factor CFA with an additional unmeasured latent method factor (Podsakoff, Mackenzie, Lee & Podsakoff, 2003) provided evidence that common method bias was not a threat because this model did not show a significantly better goodness of fit (χ;2 = 114.33, df = 93, p > 0.01, RMSEA = 0.03, GFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.99, NFI = 96, NNFI = 0.99; Δχ;2 = 0.54, df = 1, p > 0.05), Table 1 depicts descriptive statistics, correlations, and coefficient alphas for all the revised scales used in this study.

Moderated Mediation Results

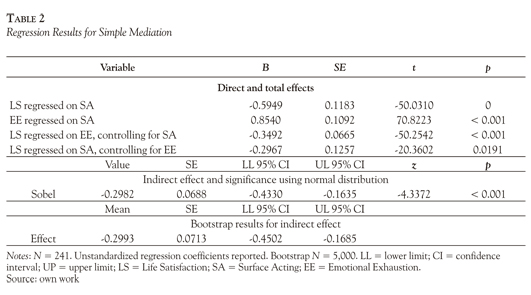

Table 2 shows that the indirect effect of surface acting on life satisfaction through emotional exhaustion with no moderator in the model was found to be significant by using Preacher et al.' (2007) procedure, in order to obtain the product of coefficients approach using second-order SE estimate (Sobel z = -4.3372, p < 0.001) as well as bootstrapped confidence interval (95% CI: {-0.4502 -0.1685} with 5,000 resamples). The signs of the path coefficients and indirect effect are consistent with the interpretation that surface acting increases emotional exhaustion, which in turn decreases the level of life satisfaction.

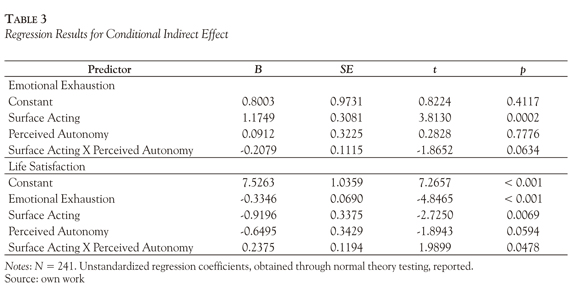

As Table 3 shows, Preacher et al.'s (2007) test showed that the interaction between surface acting and perceived autonomy was significant at a level of 0.1.

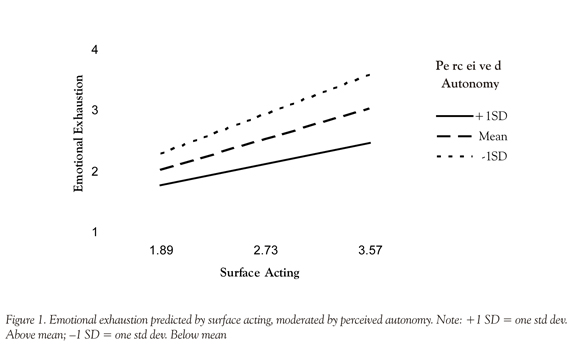

Figure 1 shows how the strength of the relationship between the surface acting and the emotional exhaustion becomes weaker as people report higher levels of autonomy. The Johnson-Neyman technique shows that the indirect effect of surface acting on life satisfaction through emotional exhaustion is significant at a level of 0.05 when individuals report perceived autonomy in the engagement of emotional labor at levels of 3.77 or lower. This result is consistent with the bootstrapping procedure, which shows that the indirect effect is significant when perceived autonomy is lower than 3.8. These results support the hypothesized model when surface acting is the form of emotional labor (Model 1).

Regarding Model 2, the indirect effect of deep acting on life satisfaction through emotional exhaustion with no moderator in the model was found to be not significant using the two Preacher et al.'s (2007) procedures described above (second-order SE estimate Sobel z = -1.6358, p < 0.1019; bootstrapped confidence interval (95% CI: {-0.2013 0.0140} with 5,000 resamples). Preacher et al.'s (2007) test shows the deep acting and perceived autonomy interaction was not significant ( p > 0.1). The Johnson-Neyman technique, consistent with the bootstrapping procedure, shows the indirect effect of surface acting on life satisfaction, through emotional exhaustion is not significant at any level of perceived autonomy ( p > 0.05). Thus, the hypothesized model is not supported when deep acting is the form of emotional labor (Model 2).

Discussion

We sought to examine the interactions between emotional labor in one's job and the level of autonomy that employees perceive they have over the job requirement to engage in emotional labor on the proximal prediction of emotional exhaustion and the distal prediction of general life satisfaction. As expected, our results revealed that surface acting was correlated positively with emotional exhaustion and negatively with life satisfaction. However, no significant correlation was found between deep acting and emotional exhaustion or between deep acting and life satisfaction. One reason for this is that, when employees engage in deep acting, they are trying to actually feel the emotions required of them and hence less laborious. Employees who share the motives or purpose with their organizations tend to experience more basic and deeper emotions (i.e., deep acting). This alignment of values may lead to deeper acting not necessarily laborious.

Ryan and Deci's Self-Determination Theory (2002) was, for the most part, supported in this study. We found that autonomy was a significant moderator between surface acting and emotional exhaustion such that the higher the perceived autonomy, the lower the indirect effect of surface acting (of emotional labor) on people's life satisfaction through emotional exhaustion. Although deep acting was found to be negatively and significantly correlated with autonomy, moderated mediation analyses revealed that, unlike surface acting, deep acting was not predictive of negative life satisfaction (as an indirect effect through emotional exhaustion). This suggests that the interaction between deep acting and autonomy to engage in emotional labor appears to be less emotionally exhausting and less damaging to one's life satisfaction than is surface acting.

Implications and Future Directions

This study makes several valuable contributions to the literature. First, this study has attempted to study the two types of emotional labor and note the differences between them instead of seeing the different types under one umbrella. This is a valuable contribution. The different results we obtained for each type of emotional labor tend to suggest that combining them under a single category may be overlooking the dynamics and intricacies involved in each of them and in how they affect employees who engage in them. Clearly, future researchers should keep this in mind when examining emotional labor and its antecedents and consequences.

Another important contribution of this study was including life satisfaction as our criterion. We attempted to study whether the different types of emotional labor tend to affect one's life satisfaction differently. Studies on emotional labor typically tend to focus on outcome factors that are of immediate organizational interest including variables such as job satisfaction, and workers' productivity (Wong, Wong & Law, 2007). Although life satisfaction can be influenced by factors beyond emotional labor, it cannot be denied that one's work and personal lives are not completely separable. The individuals tend to carry emotions and feelings from their workplace to home, and vice versa (Grzywacz & Marks, 2000). More research is warranted here.

An interesting finding of our study was that surface acting and deep acting tended to show different results, both work-related and non-work related. Surface acting is certainly more damaging in that it can result in individuals being emotionally exhausted which, in turn, can contribute to lower life satisfaction. Glomb and Tews (2004), in their study on emotional labor and emotional exhaustion, also found that surface acting was more damaging to an individual. It is possible that when employees have to engage in behaviors that are not reflective of their true self, they may experience emotional dissonance (Morris & Feldman, 1996), which can eventually lead to emotional exhaustion. A similar indirect effect on life satisfaction was not found for deep acting. Perhaps what the organizations can do is to encourage their employees to approach emotional labor duties using the principles behind deep acting where the focus is on changing one's inner feelings. If the employees can learn to internalize their job expectations (involved in emotional labor), they may be more likely to not view such job expectations as chores they have to do. As such, training in emotional regulations where one voluntarily regulates the emotions that he or she is experiencing is advisable.

In addition to training, the organizations may want to take steps to increase the employee's sense of autonomy in engaging in emotional labor. Although some job-required duties have to be carried out without any alternatives available, it is advisable that the organizations come up with innovative ways to reduce the negative impact of surface acting at least to some extent. Organizations may consider providing employees with as much help as possible to minimize ill effects that can come from engaging in emotional labor at work. More innovative means should be developed to ensure that employees do not feel trapped in their job responsibilities (that involve emotional labor).

Finally, the current study examined life satisfaction as the distal outcome of emotional labor, with emotional exhaustion as the mediating variable. However, there are numerous outcomes that are worthy of exploring, such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and job performance, as well as other variables that may mediate the relationships, such as other dimensions of burnout. Therefore, we urge future researchers to examine other outcome variables in addition to life satisfaction, as well as other mediating variables in addition to emotional exhaustion.

Limitations

The study was carried out on classified employees working in a university with its own characteristics and available resources. Hence, the results may not be applicable to other professions requiring emotional labor. Further, the response rate of 29% consisted of predominantly females. As such, it is unclear whether the results of this study will generalize to samples that are predominantly male or where a greater response rate is obtained. The cross-sectional nature of the sample, which limits the causality of relationships identified in this study, may also be a limitation. We acknowledge that the concepts of interest can be shuffled around in a random fashion because of the absence of longitudinal data. However, we do not consider these issues to be serious limitations because this research project is original, trying to study a population that has not been studied in research pertaining to emotional labor. Second, the aim of our study was to not analyze or explain the changes in the population with regard to the tested model. A longitudinal study would have been more ideal then. Instead, we were interested in seeing how the variables and model we proposed would work among a larger section of the population. Finally, our study analyzed the proximal and distal effect of emotional labor with an appropriate statistical mediation analyses (i.e. Preacher's statistical model).

Conclusion

In sum, the current study revealed that the extent to which employees experience negative repercussions from engaging in emotional labor, whether heightened emotional exhaustion or decreased life satisfaction, is partly determined by the employees' perceptions of their autonomy over engaging in such emotional labor. Overall, our hypotheses that the extent to which employees feel they have autonomy to engage or not in emotional labor acts as a moderator for the relationships between emotional labor (surface acting) and emotional exhaustion, which in itself can lead to lower life satisfaction. More research is certainly needed to understand the dynamics of emotional labor and its effect on employees' physical and psychological health from both positive and negative perspectives.

References

Ashforth, B. E., Kulik, C. T. & Tomiuk, M. A. (2008). How service agents manage the person-role interface. Group and Organization Management, 33(1), 5-45. [ Links ]

Best, R. G., Downey, R. G. & Jones, R. G. (1997, April). Incumbent perceptions of emotional work requirements. Paper presented at the 12th Annual Conference of the Society for Industrial Organizational Psychology, St Louis, Missouri, USA. [ Links ]

Brotheridge, C. M. (2006). The role of emotional intelligence and other individual difference variables in predicting emotional labor relative to situational demands. Psicothema, 18(Suppl. 1), 139-144. [ Links ]

Brotheridge, C. M. & Grandey, A. A. (2002). Emotional labor and burnout: Comparing two perspectives of 'people-work.' Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(1), 17-39. [ Links ]

Brotheridge, C. M. & Lee, R. T. (1998, August). On the dimensionality of emotional labor: Development and validation of the Emotional Labor Scale. Paper presented at the First Conference on Emotions in Organization Life, San Diego, California, USA. [ Links ]

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F. & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499-512. [ Links ]

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J. & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75. [ Links ]

Gagné, M. & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331-362. [ Links ]

Gil-Monte, P. R. & Peiró, J. M. (1999). Validez factorial del Maslach Burnout Inventory en una muestra multiocupacional. Psichotema, 11(3), 679-689. [ Links ]

Gil-Monte, P. R. & Zuñiga-Caballero, L. C. (2010). Validez factorial del "Cuestionario para la Evaluación del Síndrome de Quemarse por el trabajo" (CESQT) en una muestra de médicos mexicanos. Universitas Psychologica, 9(1), 169-178. [ Links ]

Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotion regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95-110. [ Links ]

Grandey, A. A., Fisk, G., Mattila, A., Jansen, K. J. & Sideman, L. (2005). Is service with a smile enough? Authenticity of positive displays during service encounters. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 96(1), 38-55. [ Links ]

Glomb, T. M. & Tews, M. J. (2004). Emotional labor: A conceptualization and scale development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 1-23. [ Links ]

Grzywacz, J. G. & Marks, N. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 111-126. [ Links ]

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: The commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Links ]

Jacobs, N. & Claes, N. (2008). An autonomy-supporting cardiovascular prevention programme. Practical recommendations from Self-Determination Theory. The European Health Psychologist, 10(4), 74-76. [ Links ]

Kalbers, L. P. & Fogarty, T. J. (2005). Antecedents to internal auditor burnout. Journal of Managerial Issues, 17(1), 101-118. [ Links ]

Martínez Iñigo, D. (2001). Evolución del concepto de trabajo emocional: dimensiones, antecedentes y consecuencias. Una revisión teórica. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y las Organizaciones, 17(2), 131-153. [ Links ]

Maslach, C. (1982). Burnout: The Cost of Caring. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

Melamed, S., Shirom, A., Toker, S. & Shapira, I. (2006). Burnout and risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective study of apparently healthy employed persons. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68(6), 863-869. [ Links ]

Morris, J. A. & Feldman, D. C. (1996). The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Academy of Management Journal, 21 (4), 989-1010. [ Links ]

Moyano Díaz, E. E., Flores Moraga, E. & Soromaa, H. (2011). Fiabilidad y validez de constructo del test MUNSH para medir felicidad, en población de adultos mayores chilenos. Universitas Psychologica, 10(2), 567-580. [ Links ]

Quintana, C. G. (2005). El síndrome de burnout en operadores y equipos de trabajo en maltrato infantil grave. Psykhe, 14(1), 55-68. [ Links ]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879-903 [ Links ]

Preacher, K. J., Ruckers, D. D. & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addre ssing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185-227. [ Links ]

Rafael, A. & Sutton, R. I. (1987). The expression of emotion in organizational life. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 1-42). Greenwich: JAI Press. [ Links ]

Reeve, J. (2002). Self-determination theory applied to educational settings. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 183-203). Rochester, NY: University Of Rochester Press. [ Links ]

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of self-determination theory. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3-33). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. [ Links ]

Schaubroeck, J. & Jones, J. R. (2000). Antecedents of workplace emotional labor dimensions and moderators of their effects on physical symptoms. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2¡ (2), 163-183. [ Links ]

Wong, C. S, Wong, P. M. & Law, K. S. (2007). Evidence on the practical utility of Wong's emotional intelligence scale in Hong Kong and Mainland China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(1), 43-60. [ Links ]

Zammuner, V. L., Lotto, L. & Galli, C. (2003). Regulation of emotions in the helping professions: Nature, antecedents and consequences. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 2(1), 1-13. [ Links ]