Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.12 no.3 Bogotá July/Sep. 2013

Associations between Psychosocial Functioning and Academic Achievement: The Peruvian Case

Asociaciones entre funcionamiento psicosocial y rendimiento académico: el caso peruano

Denisse Lisette Manrique Millones*

Karla Van Leeuwen**

Pol Ghesquière***

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, België

*Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium. Post doc at the Research Unit of Parenting and Special Education. ResearcherID: H-7286-2013. E-mail: denissemanriquemillones@gmail.com

**Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium. PhD, is professor at the Research Unit of Parenting and Special Education. E-mail: karla.vanleeuwen@ppw.kuleuven.be

***Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium. PhD, is professor at the Research Unit of Parenting and Special Education. E-mail: pol.ghesquiere@ppw.kuleuven.be

Recibido: marzo 21 de 2012 | Revisado: agosto 23 de 2012 | Aceptado: diciembre 18 de 2012

Para citar este artículo

Manrique Millones, D. L., Van Leeuwen, K., & Ghesquière, P. (2013). Associations between psychosocial functioning and academic achievement: The Peruvian case. Universitas Psychologica, 12(3), 725-737. doi:10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY12-3.apfa

Abstract

This study investigated (a) how specific aspects of psychosocial functioning (behavioral problems and global self-worth) are associated with academic achievement in spelling, arithmetic and reading; and (b) what is the effect of type of school (private vs. public) on this association. The sample for this study consisted of 901 regular school children attending 6th grade of primary education, living in the urban zones of Metropolitan Lima, Peru. Our research hypotheses were partially corroborated. The results showed a strong relationship between academic achievement and psychosocial functioning, with an important role of gender and school failure at the student level. Nevertheless, we could not confirm our multilevel assumption. There is no evidence that this relationship differs among schools. Practical implications are discussed.

Key words authors: Self-worth, behavioral problems, academic achievement, childhood, Peru.

Key words plus: Quantitative Research, Educative Psychology, Development Psychology

Resumen

Este estudio investigó: (a) como los aspectos específicos del funcionamiento psicosocial (problemas de comportamiento y autoestima en general) son asociados con el logro académico en la ortografía, aritmética y lectura, y (b) cuál es el efecto del tipo de escuela (privada o pública) de esta asociación. La muestra de este estudio consistió en 901 niños de escuelas regulares que asisten a sexto grado de educación primaria, que viven en las zonas urbanas de Lima, Perú. Nuestra hipótesis de investigación fue corroborada parcialmente. Los resultados mostraron una fuerte relación entre el rendimiento académico y el funcionamiento psicosocial, con un papel importante de género y el fracaso escolar en el nivel de los estudiantes. Sin embargo, no se pudo confirmar nuestra hipótesis de multinivel. No hay evidencia de que esta relación difiera entre las escuelas. Se discuten las implicaciones prácticas.

Palabras clave autores: Autoestima, problemas de comportamiento, rendimiento académico, infancia, Perú.

Palabras clave descriptores: Investigación cuantitativa, psicología educativa, psicología del desarrollo.

doi:10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY12-3.apfa

Extensive research has been done in an attempt to understand the inter-relation of academic achievement and non-cognitive outcomes such as psychosocial functioning (Chen, Rubin, & Li, 1997; Elias & Haynes, 2008; Mashburn et al., 2008; Sektnan, McClelland, Acock, & Morrison, 2010; Stipek & Byler, 2001; Zins, Weissberg, Wang, & Walberg, 2004).

A substantial body of research has documented that the academic achievement also influences the psychosocial area (Gadeyne, Ghesquière, & Onghena, 2004; Gil, Palomera, & Brackett, 2006; Rhoades, Warren, Domitrovich, & Greenberg, 2011; Rhodes, 2009; Swanson, Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant, & O'Brien, 2011). Over the past 30 years, attention has been directed to this socio-emotional side of cognitive outcomes. Henceforth, it is undeniable that students with low academic achievement are characterized by some psychosocial deficits. Several comprehensive reviews have identified in detail the psychosocial functioning of low academic achievers (Möller & Pohlmann, 2009). Traditional techniques, such as narratives, as well as more sophisticated ones, like meta-analyses, have been used to enhance our understanding and determine the extent of psychosocial difficulties in learning disabled people.

Findings have shown that low achievers are more likely to manifest psychosocial problems. In general, although there have been a few studies that did not reveal any relationship, most studies showed an association between psychosocial problems and academic achievement deficit. Among the co-occurring problems social disorders and emotional problems are mentioned. The former is mainly characterized by a lack of social competence, involving situations of social rejection, lack of sensitivity to others and a poor perception of social circumstances (Barriga et al., 2002; Woodward & Fergusson, 2000). In the case of the latter, feelings of frustration and self-derision are commonly encountered. Emotional problems include internalizing issues (such as sadness, fear of success, withdrawal to a private world, depression, anxiety, low self-worth and motivation) and externalizing issues (in the manner of acting out behaviors, excessive anger and hostility).

The study of psychosocial factors in academic achievement is relevant because of their detrimental impact to the child's abilities to socialize and achieve academically. In this study, attention was specifically given towards two main areas of the psychosocial domain: global self-worth and behavioral problems. These areas were chosen among other specific domains because of their high value for children with academic problems (Clever, Bear, & Juvoren, 1992), and their role in the enhancement of academic achievement (Kavale & Forness, 1987).

Global self-worth is conceptualized by Harter (1999, p. 5) as "the overall evaluation of one's worth or value as a person". More than a mere self-perception of capabilities, whether social, academic or physical, it assesses satisfaction, happiness and thorough affection towards oneself. There is a wide body of research reporting the important role that self-worth plays as a co-occurrence of academic underachievement. A repeated academic failure leads to inevitable dissatisfaction, frustration and hence a negative view of oneself. However, mixed findings have been reported. Whereas some studies have highlighted the strong relationship between low self-worth and academic underachievement (Crocker & Niiya, 2008; Lawrence & Crocker, 2009), others have reported no association between them (Trautwein, Lüdtke, Köller, & Baumert, 2006). Because of these mixed results, we further want to explore self-worth in association with academic achievement.

A great number of studies have found significant associations between academic underachievement and behavioral problems, such as aggression (Connor, 2002), anxiety (Owens, 2009), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Loe & Feldman, 2007) and depression (Grimm, 2007), to mention some of them. A group of negative behaviors has been attributed to underachievers, with two possible tendencies: to be withdrawn or to develop disruptive behaviors (Roberts, Pratt, & Leach, 1990).

Despite the relevance of studying the association between psychosocial functioning and academic achievement, this issue has not yet been addressed in a Peruvian reality, by means of a study that properly involves both variables. In a study with Chilean children and adolescents, De la Barra (2010) showed evidence for a group of risk (emotional immaturity and cognitive concentration problems) and protective factors (child's autonomy, good teacher-student relationship) that were associated with some disorders such as psychopathology in family relationships, low academic achievement, adolescent depression, and others (De la Barra, Toledo, & Rodríguez, 2005; Fischer, Gunnar, Dozier, Bruce, & Pears, 2006).

Children can also be influenced by the social climate at school and peer interactions that often take place. For the student the school is not only an environment for learning but is also a place for social activities (Hofman, Hofman, & Guldemond, 1999; Villalta & Saavedra, 2012).

In Peru, we can find two different kinds of educational management: private and public schools. These environmental factors (e.g. school components) could be associated with individual social functioning. In this regard, although there is scarce literature available, some studies have shown the impact of the type of school or classes on non-cognitive outcomes (e.g. Konu, Lintonen, Opdenakker, & Van Damme, 2000; Van Landeghem, Van Damme, Opdenakker, De Fraine, & Onghena, 2002).

In order to counter the lack of Latin studies in this domain, we aim to investigate some psychosocial factors (behavioral problems and global self-worth) and further elaborate on their relation with academic achievement in Peruvian children from different classrooms and schools in 6th grade. Furthermore, we intend to close some gaps between the environmental factors (e.g. school) and psychosocial outcomes (behavioral problems and self-worth). Based on previous theoretical considerations and research findings, the present article addresses the following research questions: Does the academic achievement measured by spelling, reading and arithmetic is related to psychosocial functioning of children in terms of behavioral problems and global self-worth, and does this relationship differs among schools?

Method

Participants

901 spanish speaking Peruvian children formed the sample. All the subjects were regular elementary school children attending sixth grade, they were spread over 45 classes in 17 different schools, and were located in urban zones of the Metropolitan Lima. Their age ranged from 10.5 to 13.3 years old (M = 11.54; SD = 0.43). From the total sample, 422 (46.8%) participants were boys and 479 (53.2%) were girls. Regarding the type of school, 496 (55%) came from public schools and 405 (45%) from private schools.

Instruments

For the purpose of the study, the English version of a global self-worth questionnaire, The Perceived Competence Scale for Children (Harter, 1982), was translated into Spanish, followed by a backtranslation from Spanish into English. Three Spanish- speaking researchers, fluently in English and aware of the Peruvian context, commented on this new version of the questionnaire. For the rest of the scales, we used available Spanish versions. A detailed description regarding the academic achievement tools used can be found in Manrique Millones, Van Leeuwen, and Ghesquière (2011).

Spelling

Spelling was assessed by means of the Orthography Achievement Test (Dioses, 2001), which assesses three aspects of general orthography: literal orthography, accentual orthography and punctual orthography. Each aspect was measured through a task. In the first task, the evaluator dictated 11 words for the pupils. In the second task, the evaluator dictated little sentences in addition to words, to a total of 12 items. The third and last part consisted of four tasks; the first two are related to accurately locating punctuation signs: in the first case, the correct use of comma (,) and in the second case the correct use of the colon (:). Two sentences were presented in each part. In the third task, the child is asked to write two sentences that were dictated by the evaluator, this task assesses the correct use of question marks (?), so the correct intonation of the instructor is very important. Finally, in the fourth part, the student is asked to locate exclamations marks (!) within two sentences. Internal consistency was measured by means of Cronbach alpha's, ranging from 0.65 to 0.81.

Arithmetic

In the area of Arithmetic, we used the "Number Facility" subtest of the Ekstrom, French, and Harman (1976) battery, intended to measure speed and accuracy in basic arithmetic operations. We obtained an internal consistency ranging from 0.71 to 0.82, representing its adequacy. In the first task, the pupil was asked to solve as many addition operations as possible in 2 minutes, for two sets of 60 items, with three addends of one or two digits. Similarly to the first task, the second one consisted of two sets of 60 operations. However, in this case, the student had to divide two or three digit numbers by single digit numbers. The third task alternated between ten subtractions between two digit numbers and ten multiplications of two digit numbers by single digit numbers, up to a total of 120 operations, split by two parts of identical length.

Reading

To assess reading, a subtest of PROLECSE test "Word and Pseudo-word Reading" was used. This instrument was developed and standardized by Ramos and Cuetos (1999) proving its validity in Spanish-speaking contexts. Reliability by means of Cronbach alpha's was tested, reaching a = 0.78. The test consisted of two tasks presented to the student. In the first task, the pupil had to read out loud, as accurately and as fast as possible, a list of 40 words that contains 2, 3, 4, and 5 syllables. The evaluator marked each word that the child read incorrectly. The second task was similar to the first (reading a list of 40 words between 2 and 5 syllables), but with a list comprised of pseudo-words. The completion time was measured for each task. The total scored used was the amount of word read correctly in 1 minute.

Behavioral Problem

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire ([SDQ]; Goodman, 1997) was applied in order to measure behavioral problems. The SDQ is a brief behavioral questionnaire for children between 3 -16 years. It is a 25 items scale in which the teacher or a parent has to mark for each psychological attribute (some of them positive and some negative) whether it is "Not True", "Somewhat True" or "Certainly True". These 25 items are attributed to five sub-scales with five items each and can have a score between 0 and 10. For means of this article we only used and analyzed three sub-scales but hyperactivity and prosocial. Cronbach alpha's for the three subscales ranged from 0.52 to 0.81. Previous studies have proven the adequate psychometric properties (Goodman, 2001) of SDQ as a reliable and useful tool of the adjustment of children and adolescents. Emotional symptoms, refers to the symptoms affecting the child emotions (e.g. "Often he /she is unhappy, downhearted or tearful"); conduct problems, measures aggressive activities that cause disruptions in the child's natural environments (e.g. "Often fights with other children or bullies them"); peer relationship problems, assesses the relationship with peers. Peers actively reject some children; others are ignored, or neglected (e.g. "Rather solitary, tends to play alone").

Self-Worth

The Perceived Competence Scale for Children (Harter, 1982) was used to evaluate self-worth through the assessment of a child's sense of competence across different domains, and explores the judgments and opinions that children have about their competence as well as an overall perception of his/her esteem as a person. It is a self-report instrument consisting of 36 items distributed in six scales: Scholastic competence, social acceptance, global self-worth, athletic competition, physical appearance and behavior. For means of this article we only used and analyzed the first three sub-scales. Cron-bach alpha's for the three subscales ranged from 0.46 to 0.64. Scholastic competence, measures the perception of children about their competence or ability in school performance; all items are related to school; social acceptance, evaluates the degree to which the child is accepted by their peers or feels popular; general self-worth, analyzes to what extent the child likes and feels pleased with themselves as a person, whether they are satisfied with the way they are as a whole.

Procedure

Schools were randomly selected in Metropolitan Lima. The first contact with the schools were made by telephone, a second contact was made personally in order to explain in detail the research aims. After having authorization of the schools, an information letter in a sealed envelope was sent to parents of private schools. The letter gave an explanation of the study and a written consent was requested. By contrast, in public schools a talk was given to parents and an oral consent was received.

Data collection consisted of three sessions of 45 minutes each. In the first session arithmetic and spelling were tested, in the second session reading was evaluated and finally in the third, the global self-worth questionnaire was presented. Between evaluations a ten-minute break was given, if applicable. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman, 1997) was filled out by the tutor of each classroom. All tests were carried out collectively in regular school hours, the only exception was reading, which took place individually leading the child to an adjoining classroom.

Statistical Analysis

To answer the main research questions in this study, multivariate multilevel analyses were conducted with Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). A model fit was evaluated through the inspection of several fit indexes: the chi squared statistic (%2), the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI). In order for a model to have a good fit, the RMSEA should be equal or lower than 0.06, and the CFI should be close to 0.95 or higher (Hu & Bentler, 1999). A RMSEA value lower than 0.08 and a CFI statistic equal to 0.9 or higher indicate an acceptable fit (Byrne, 1998; Kline, 1998).

Following our theoretical rationale, two models were tested separately. The first model tested the relationship between behavioral problems and academic achievement, whereas the second model tested the association of self-worth and academic achievement.

Results

Descriptive Information

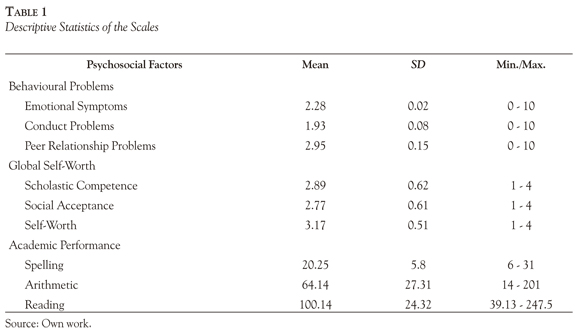

We identified an average of 48.93 students per school, with a range of 8 to 152 students. In Table 1 we report the descriptive information for our outcome variables (including mean M, standard deviation SD and minimum/maximum value).

Conceptual Model for Behavioral Problems and Academic Achievement

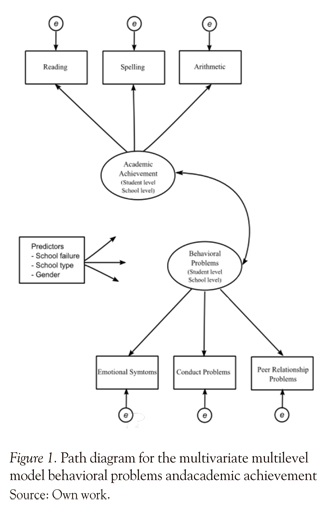

Figure 1 represents the path diagram for the multivariate model. In this model two latent variables were assumed, behavioral problems and academic achievement at the student and school level. Furthermore, six continuous variables, three in the case of behavioral problems (emotional symptoms, conduct problems and peer relationship problems), and three in the case of academic achievement (reading, spelling and arithmetic). Additionally, three predictors were added in the model: school failure, gender and school type.

Multivariate multilevel results

In the first part of the analyses the proportion of the variance explained by the grouping structure in the population, was calculated. Therefore, the intraclass coefficient (ICC) was estimated in the three academic areas obtaining: ICCSP = 0.31, ICCAR = 0.28 and ICCRE = 0.23, which means that 30 %, 28 % and 23 % of the variance is situated at the school level in spelling, arithmetic and reading respectively. Moreover, the ICC for behavioral problems subscales was calculated: ICCES = 0.17, ICCCP = 0.09, ICCPRP = 0.07, which means that 17 %, 9 % and 7 % of the variance is situated at the school level in emotional symptoms, conduct problems and peer relationship problems respectively.

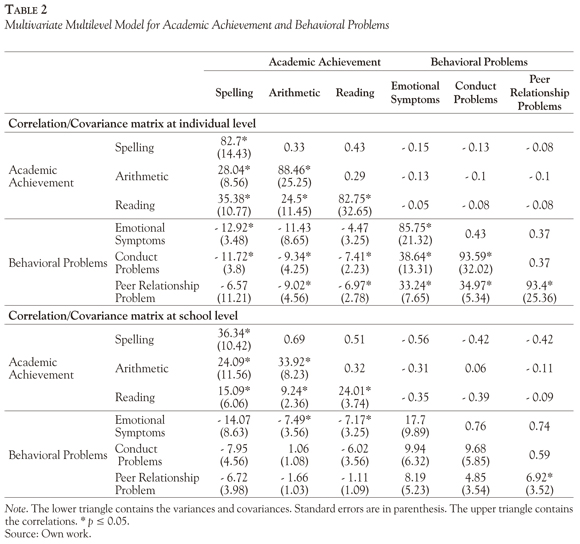

The testing of the conceptual model for behavioral problems and academic achievement yielded an adequate fit x2 (58) = 119.38, p = 0.09; RMSEA = 0.038; CFI = 0.91. At the student level, there was a significant and negative correlation between academic achievement and behavioral problems (r = -0.26).

The correlation/covariance matrix at the student level indicated a negative relationship between behavioral problems and academic achievement, which can be interpreted as students that perform high in academic achievement by means of spelling, reading or arithmetic tend to have less behavioral problems, specifically in the domains of emotional symptoms, conduct problems and peer relationship. Between the academic domains (Table 2), all correlations were positive with the highest correlation between spelling and reading (r = 0.43). Regarding the behavioral problems subscales positive intercorrelations were present, ranging from r = 0.37 to r = 0.43.

The correlation / covariance matrix at the school level indicated that schools have a stronger effect on academic achievement than on behavioral problems, meaning that schools make more difference in academic achievement than in behavioral problems.

Regarding the predictors, we did not find any effect of them on the conceptual association (academic achievement and psychosocial functioning) neither at school nor the student level. Nevertheless, at the student level, we found an effect of school failure on academic achievement (ß = -0.22), meaning that students that experience school failure will show low academic achievement. Likewise, the results showed an effect of gender on behavioral problems (ß = 0.28), with boys showing more behavioral problems than their female peers.

Conceptual model for global self-worth and academic achievement

Figure 2 depicts the path diagram for the second multivariate model. In this model two latent variables were assumed, global self-worth and academic achievement at the student and school level. Furthermore, six continuous variables, three in the case of global self-worth (scholastic competence, social acceptance and self-worth) and three in the case of academic achievement (reading, spelling and arithmetic). Additionally, three predictors were added in the model: school failure, gender and school type.

Multivariate multilevel results

In the first part of the analyses, the proportion of the variance explained by the grouping structure in the population, was calculated. Therefore, the intraclass coefficient (ICC) was estimated in the three academic areas obtaining: ICCSP = 0.23, ICCAR= 0.33 and ICCRE = 0.2, which means that 23%, 33% and 20% of the variance is situated at the school level in spelling, arithmetic and reading, respectively. Furthermore, the ICC for behavioral problems subscales was calculated: ICCSC = 0.01, ICCSA = 0.1, ICCSW = 0.04, which means that 1 %, 10 % and 4 % of the variance is situated at the school level in scholastic competence, social acceptance and self-worth, respectively.

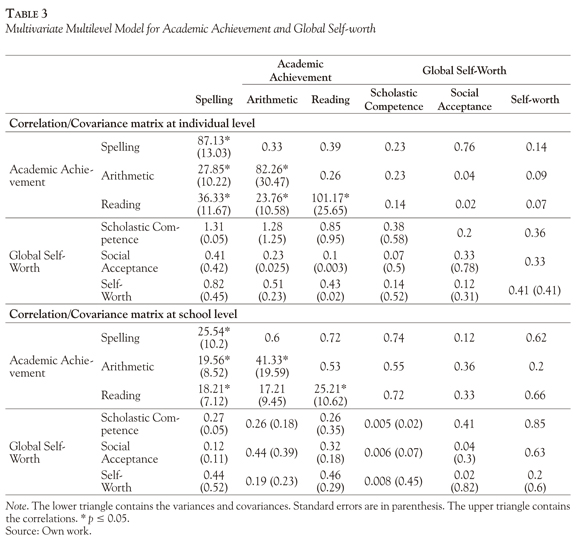

The testing of the second model for behavioral problems and academic achievement yielded a good fit x2 (52) = 145.55, p > 0.05; RMSEA = 0.05; CFI = 0.87. At the student level, there was a significant and positive correlation between academic achievement and global self-worth (r = 0.29).

The correlation / covariance matrix at the student level indicated a positive relationship between global self-worth and academic achievement, meaning that students with high performance in academic achievement on the domain of spelling, reading or arithmetic tend to report a high self-worth as well, specifically in the domains of scholastic competence, social acceptance and global self-worth. Between the academic domains (Table 3), all correlations were positive with the highest correlation between spelling and reading (r = 0.39). The self-worth subscales were positively inter-correlated, ranging from r = 0.20 to r = 0.36.

The correlation / covariance matrix at the school level indicated that school has a stronger effect on academic achievement than on self-worth. This was also the case with behavioral problems, meaning that schools make a stronger difference for academic performance than for behavioral problems. Concerning our predictors, we did not find significant effects of them over the conceptual association (academic achievement and psychosocial functioning) neither at school nor student level. Only at the student level, we found an effect of school failure on academic achievement (ß = -0.17), meaning that students experiencing school failure also show low academic performance.

Discussion

The goal of this study was twofold: (a) examining the associations between academic achievement, with spelling, reading and arithmetic as indicators, and psychosocial functioning, in terms of behavioral problems (emotional symptoms conduct problems and peer relationship problems) and global self-worth (scholastic competence, social acceptance and self-worth) and (b) investigating the effect of school on this association. The expected associations between academic achievement and psychosocial functioning in a multilevel structure were partially confirmed.

Regarding our first research question and in line with previous studies (Gadeyne et al., 2004; Greenham, 1999), we found a relationship between different academic achievement domains and psychosocial variables (behavioral problems and self-worth). Moreover, the results showed also the impact of other related variables such as school failure and gender. The results showed that children with low academic achievement tend to view themselves more negatively than the rest of the peer group, in accordance with the results of Saracoglu, Minden, and Wilchesky (1989) and Valas (1999). Self-worth problems may emerge when children contend their academic problems as a consequence of experiencing constant school failure. Their constant feelings of disappointment and frustration are somehow reflected in their own self-worth and probably with a latent risk of forthcoming more academic problems. Notwithstanding, Marsh (2007) highlights that this is not always the case. Other factors may prevent academic deficits from affecting their self-worth. Attention should be given to some studies that adduce some lower achievers to have self-worth scores comparable to their matched peers who are not lower achievers (Bear & Minke, 1996; Clever et al., 1992).

A similar situation is found for the behavior problems variable, in which the strong connection between academic problems and deficits in self-control and self-regulating behaviors is evident. A great body of evidence has demonstrated that most individuals with achievement deficits undergo social difficulties along with their academic problems (Handwerk & Marshall, 1998; McGee, Prior, Williams, Smart, & Sanson, 2002). Experimental research (Milich, McAntinch, & Harris, 1992) has documented that when a child is categorized with behavior problems, peers tend to reject and behave negatively towards this child. Moreover, the children displaying such misbehaviors respond in a negative way aggravating this interaction.

Results also revealed gender and school failure as good predictors of behavioral problems and self-worth respectively. Research literature consistently confirms a tendency for boys to have more problems than girls (Calvete & Cardeñoso, 2005; Yanyun, Huijun, Ying, Jenn-Yun, & Xianchen, 2008). In a study conducted by van der Meer, Dixon, and Rose (2008) parents considered that boys were likely to have more externalizing problems (e.g. conduct disorder), whereas girls showed a higher rate in internalizing problems (e.g. mood disorder).

As our results showed, poor academic performance cooccurs with externalizing behavioral problems (Hawkins, Farrington, & Catalano, 1998; Huizinga & Jakob-Chien, 1998). Nevertheless it is important to clarify that academic failure may correlate with behavioral problems in general, but it does not predict specific forms of antisocial behavior. In this case other variables, particularly family and peer dynamics, intervene to shape the direction and severity of troublesome conduct (McEvoy & Welker, 2000).

Concerning our second research question we did not find evidence for variation among schools. Unlike previous studies (Manrique Millones et al., 2011; Rivkin, Hanushek, & Kain, 2005) where school plays a pivotal role in academic achievement, in the present study this role is diminished or disappears when combined with psychosocial functioning. We have to take into account that there might be other factors that could intervene in the relationship of academic achievement and psychosocial functioning. With this respect, the support (or negligence) that parents can give to their children, how committed and involved they are with their child's academic world is very important.

One of the limitations of our study is related to the cross-sectional nature of the data. Therefore we are not able to describe development or changes in the characteristics of the target population at neither the group nor the individual level. A longitudinal study is more likely to suggest cause-and-effect relationships than a cross-sectional study by virtue of its scope; this is the reason why we need to treat our results with precaution.

Overall, three concluding points should be highlighted. First, we corroborated strong links between academic achievement and psychosocial adjustment. Second, we found gender and school failure as good predictors of behavioral problems and academic achievement. And finally, although we did not find support for the multilevel assumption of our constructs' association, we should think about the presence of contextual or external factors that might intervene in the process. We previously mentioned the role of the family, but also the teacher might have an important role. In a study conducted by Henricsson and Rydell (2004) it was demonstrated that poor teacher-student relationships tend to have a negative effect on school adjustment. Likewise, students who do not meet teacher expectations are at risk for social and academic failure (Lane, Wehby, & Cooley, 2006), because of rejection by their teachers.

Students with academic deficits or adolescents that exhibit psychosocial problems might be at risk for posterior psychological maladjustment (Parker & Asher, 1987). It is advisable, if possible, to meet the learning needs or demands of these children in order to prevent them from developing insecurity, lack of self-confidence and even disruptive behavior.

References

Barriga, A., Doran, J., Newell, S., Morrison, E., Barbetti, V., & Robbins, B. (2002). Relationships between problem behaviors and academic achievement in adolescents. The unique role of attention problems. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 10(4), 233-240. [ Links ]

Bear, G. G., & Minke, K. (1996). Positive bias in maintenance of self-worth among children with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 19(1), 23-32. [ Links ]

Byrne, B. (1998). Structural equation modeling with PRELIS, LISREL and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [ Links ]

Calvete, E., & Cardeñoso, O. (2005). Gender differences in cognitive vulnerability to depression and behavior problems in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(2), 179-192. [ Links ]

Chen, X., Rubin, K. H., & Li, D. (1997). Relation between academic achievement and social adjustment: Evidence from Chinese children. Developmental Psychology, 33(3), 518-525. [ Links ]

Clever, A., Bear, G. G., & Juvonen, J. (1992). Discrepancies between competence and importance in self-perceptions of children in integrated classrooms. Journal of Special Education, 26(2), 125-138. [ Links ]

Connor, D. F. (2002). Aggression and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: Research and treatment. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Crocker, J., & Niiya, Y. (2008). Contingencies of self-worth: Implications for motivations and achievement. In M. Maehr, S. A. Karabenick, & T. C. Urdan (Eds), Advances in motivation and Social. Psychological perspectives achievement (Vol. 15, pp. 81-118). UK: Emerald Group Publishing. [ Links ]

De la Barra, F. (2010). Developmental epidemiology in children and adolescents. Revista Chilena de Neuro-Psiquiatría, 48(2), 152-159. [ Links ]

De la Barra, F., Toledo, V., & Rodriguez, J. (2005). Prediction of behavioral problems in Chilean school children. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 35(3), 227-243. [ Links ]

Dioses, A. (2001). Test de Rendimiento Ortográfico [Test of Orthography]. Lima: CPAL. [ Links ]

Ekstrom, R. B., French, J. W., & Harman, H. H. (1976). Manual for kit of factor-referenced cognitive tests. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service. [ Links ]

Elias, M. J., & Haynes, N. M. (2008). Social competence, social support, and academic achievement in minority, lowincome, urban elementary school children. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(4), 474-495. [ Links ]

Fischer, P. A., Gunnar, M. R., Dozier, M., Bruce, J., & Pears, K. (2006). Effects of therapeutic interventions for foster children on behavioural problems, caregiver attachment, and stress regulatory neural systems. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094, 215-225. [ Links ]

Gadeyne, E., Ghesquiere, P., & Onghena, P. (2004). Psychosocial functioning of young children with learning disabilities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(3), 510-521. [ Links ]

Gil, P., Palomera, R., & Brackett, M. (2006). Relating emotional intelligence to social competence and academic achievement in high school students. Psicothema, 18(Suppl. 1), 188-123. [ Links ]

Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581-586. [ Links ]

Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337-1345. [ Links ]

Greenham, S. (1999). Learning disabilities and psychosocial adjustment: A critical review. Child Neuropsychology, 5(3), 171-196. [ Links ]

Grimm, K. (2007). Multivariate longitudinal methods for studying developmental relationships between depression and academic achievement. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31 (4), 328-339. [ Links ]

Handwerk, M. L, & Marshall, R. M. (1998). Behavioral and emotional problems of students with learning disabilities, serious emotional disturbance, or both conditions. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 31(4), 327-338. [ Links ]

Harter, S. (1982). The Perceived Competency Scale for Children. Child Development, 53(1), 87-97. Retrieved December, 2011, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1129640 [ Links ]

Harter, S. (1999). The construction of the self. New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Hawkins, J. D., Farrington, D. P., & Catalano, R. F. (1998). Reducing violence through the schools. In D. S. Eliot, B. A. Hamburg, & K. R. Williams (Eds.), Violence in American schools: A new perspective (pp. 188-216). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Henricsson, L., & Rydell, A. (2004). Elementary school children with behavior problems: Teacher-child relations and self-perception. A prospective study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50(2), 111-138. [ Links ]

Hofman, R. H., Hofman, A. W. H., & Guldemond, H. (1999) . Social and cognitive outcomes: A comparison of contexts of learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 10(3), 352-366. [ Links ]

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling, 6(1), 1-55. [ Links ]

Huizinga, D., & Jakob-Chien, C. (1998). The contemporaneous cooccurrence of serious and violent juvenile offenders and other problem behaviors. In R. Loeber & D. Farrington (Eds.), Serious & violent juvenile offenders: Risk factors and successful interventions (pp. 47-67). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Kavale, K. A., & Forness, S. R. (1987). The far side of heterogeneity: A critical analysis of empirical subtyping research in learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 20(6), 374-382. [ Links ]

Kline, R. (1998). Principles and practices of structural equation modelling. New York: Guildford Press. [ Links ]

Konu, A. I., Lintonen, T. P., Opdenakker, M. C., & Van Damme, J. (2000). Effect of school teaching staff and classes on achievement and well-being in secondary education. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 11 (2), 165-196. [ Links ]

Lane, K. L., Wehby, J. H., & Cooley, C. (2006). Teacher expectations of students' classroom behavior across the grade span: Which social skills are necessary for success? Exceptional Children, 72(2), 153-167. [ Links ]

Lawrence, J., & Crocker, J. (2009). Academic contingencies of self-worth impair positively- and negatively-stereotyped students' performance in performance-goal settings. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(5), 868-874. [ Links ]

Loe, I. M., & Feldman, H. M. (2007). Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 7 (Suppl. 1), 82-90. [ Links ]

Manrique Millones, D., Van Leeuwen, K., & Ghesquière, P. (2011). Academic performance of Peruvian elementary school children: The case of schools in Lima at the 6th grade. Interdisciplinaria: Journal of Psychology and Related Sciences, 28(2), 323-343. [ Links ]

Marsh, H. W. (2007). Self-concept theory, measurement and research into practice: The role of self-concept in educational psychology. Leicester, England: British Psychological Society. [ Links ]

Mashburn, A. J., Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., Downer, J. T., Barbarin, O. A., Bryant, D., Burchinal, M., et al. (2008). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children's development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development, 79(3), 732-749. [ Links ]

McEvoy, A., & Welker, R. (2000). Antisocial behavior, academic failure, and school climate: A critical review. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 8(3), 130-140. [ Links ]

McGee, R., Prior, M., Williams, S., Smart, D. & Sanson, A. (2002). The longterm significance of teacher rated hyperactivity in childhood: Findings from two longitudinal studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(8), 1004-1017. [ Links ]

Milich, R., McAninch, C., & Harris, M. (1992). Effects of stigmatizing information on children peer relations: Believing is seeing. School Psychology Review, 21(3), 400-409. Retrieved December 2011, from http://www.minedu.gob.pe [ Links ]

Möller, J., & Pohlmann, B. (2009). A meta-analytic path analysis of the internal/external frame of reference model of academic achievement and academic self-concept. Review of Educational Research, 79(3), 1129-1167. [ Links ]

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2010). Mplus User's Guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [ Links ]

Owens, M. (2009). Exploring the role of working memory and understanding educational underachievement in anxiety and depression. Doctoral Thesis, School of Psychology, University of Southampton, UK. [ Links ]

Parker, J. C., & Asher, S. R. (1987). Peer relations and later personal adjustment: Are low accepted children at risk? Psychological Bulletin, 102(3), 357-389. [ Links ]

Ramos, F., & Cuetos, F. (1999). PROLECSE. Batería de evaluación de los procesos lectores de los niños de Educación Secundaria [PROLEC: Reading Processes Assessment Battery in Secondary School]. Madrid: TEA. [ Links ]

Rivkin, S. T., Hanushek, E. A., & Kain, J. F. (2005). Teachers, schools, and academic achievement. Econometrica, 73(2), 417-458. [ Links ]

Rhoades, B., Warren, H. K., Domitrovich, C. E., & Greenberg, M. (2011). Examining the link between preschool social-emotional competence and first grade academic achievement: The role of attention skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 26(2), 182-191. [ Links ]

Rhodes, D. (2009). An exploratory study of the relationship among perceived personal and social competence, health risk behaviors, and academic achievement of selected undergraduate students. Dissertations, Paper 75. [ Links ]

Roberts, C., Pratt, C., & Leach, D. (1990). Classroom and playground interaction of students with and without disabilities. Exceptional Children, 57(3), 212-224. [ Links ]

Saracoglu, B., Minden, H., & Wilchesky, M. (1989). The adjustment of students with learning disability to university and its relationship to self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 22(9), 590-592. [ Links ]

Sektnan, M., McClelland, M., Acock, A., & Morrison, F. (2010). Relations between early family risk, children's behavioral regulation, and academic achievement. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25(4), 464-479. [ Links ]

Stipek, D., & Byler, P. (2001). Academic achievement and social behaviors associated with age of entry into kindergarten. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 22(2), 175-189. [ Links ]

Swanson, J., Valiente, C., Lemery-Chalfant, K., & O'Brien, C. (2011). Predicting early adolescents' academic achievement, social competence, and physical health from parenting, ego resilience, and engagement coping. Journal of Early Adolescence, 31(4), 548-576. [ Links ]

Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Köller, O., & Baumert, J. (2006). Self-esteem, academic self-concept, and achievement: How the learning environment moderates the dynamics of self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(2), 334-349. [ Links ]

Valas, H. (1999). Students with learning disability and lowachieving students: Peer acceptance, loneliness, self-esteem and depression. Social Psychology of Education, 3(3), 173-192. [ Links ]

van der Meer, M., Dixon, A., & Rose, D. (2008). Parent and child agreement on reports of problem behaviour obtained from a screening questionnaire, the SDQ. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 17(8), 491-497. [ Links ]

Van Landeghem, G., Van Damme, J., Opdenakker, M. K., de Freine, B, & Onghena, P. (2002). The effect of schools and classes on non-cognitive outcomes. School of Effectiveness and School Improvement, 13(4), 429-451. [ Links ]

Villalta, M. A., & Saavedra, E. (2012). Cultura escolar, prácticas de enseñanza y resiliencia en alumnos y profesores de contextos sociales vulnerables. Universitas Psychologica, 11 (1), 55-65. [ Links ]

Woodward, L. J., & Fergusson, D. M. (2000). Childhood peer relationship problems and later risks of educational under-achievement and unemployment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(2), 191-201. [ Links ]

Yanyun, Y., Huijun, L., Ying, Z., Jenn-Yun, T., & Xianchen, L. (2008). Age and gender differences in behavioral problems in Chinese children: Parent and teacher reports. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 1(2), 42-46. [ Links ]

Zins, J., Weissberg, R., Wang, M., & Walberg, H. (2004). Building academic success on social and emotional learning. New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]