Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.13 no.1 Bogotá Jan./Mar. 2014

Analyzing the Impacts of Commitment and Entrenchment on Behavioral Intentions*

Analizando los impactos del compromiso y el afianzamiento sobre comportamientos intencionales

Alba Couto Falcão Scheible**

António Virgílio Bittencourt Bastos***

Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil

*Artículo de investigación.

**Núcleo de Pós Graduação em Administração, Universidade Federal da Bahia (Brazil); Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Alba Scheible. Address: R. Clara Nunes, 310 ap102 — Caminho das Arvores — Salvador/ Bahia/ Brazil — 41810-425. Phones: +7 701 9790030 or +55 71 88268633. Núcleo de Pós Graduação em Administração. Universidade Federal da Bahia. E-mail: ac.scheible@uol.com.br

***Núcleo de Pós Graduação em Administração, Universidade Federal da Bahia (Brazil). Address: Rua Macapá, 461, apt. 601, Ondina, 40170-150, Salvador-BA, Brasil. Phone: +55 71 88347854. Email: antoniovirgiliobastos@gmail.com

Recibido: julio 25 de 2011 | Revisado: enero 12 de 2013 | Aceptado: marzo 28 de 2013

Para citar este artículo

Falcão, A. C., & Bittencourt, A. V. (2014). Analyzing the impacts of commitment and entrenchment on behavioral intentions. Universitas Psychologica, 13(1), 109-119. doi:10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-1.aice

Abstract

The lack of a universal definition for the organizational commitment brings difficulties for improving knowledge about the construct. Following the commitment construct revision proposed by Rodrigues (2009) through the separation of its continuance dimension - now referred to as organizational entrenchment, this paper analyzed the relationships between organizational affective commitment and entrenchment with behavioral intentions. The study was conducted in a Brazilian information technology company with the participation of 307 people. The results show that organizational entrenchment is indeed a different construct than the organizational affective commitment. It was found that affective commitment to the organization is a predecessor of the intentions to stay, defend, and exert extra effort, while entrenchment displayed no relevant relationships with them.

Keywords authors: commitment; entrenchment; intentions

Keywords plus: organizational psychology; work; psychology

Resumen

La falta de una definición universal para el compromiso organizacional trae dificultades para mejorar el conocimiento acerca del constructo. Tras la revisión sobre el constructo de compromiso propuesto por Rodrigues (2009) a través de la separación de su dimensión continuidad -que ahora se conoce como afianzamiento organizacional, el presente trabajo analiza las relaciones entre el compromiso afectivo comportamental y afiancia-miento con el comportamiento intencional. El estudio fue conducido en una compañía tecnológica de información brasilera con la participación de 307 personas. Los resultados muestan que el afianciamiento organizacional es un constructo diferente del compromiso afectivo organizacional. Se ha encontrado que el compromiso afectivo a la organización es un predecesor de las intenciones para permanecer, defender, y ejercer un esfuerzo extra, mientras el afianciamiento no mostró relaciones relevantes con estos.

Palabras clave autores compromiso; afianciamiento; intenciones

Palabras clave descriptores: psicología de las organizaciones; trabajo; psicología

Work commitment has been interpreted, defined and measured in many different ways (Meyer & Herscovitch, 2001; Morrow, 1993; Mowday, Porters, & Steers, 1982) and there is not a consensus definition shared by the global research community. Conceptual redundancy occurs when constructs are not precisely defined to be mutually exclusive or when the link between conceptual definition and measurement instrument (construct validity) is not perfect. The construct of work commitment has suffered from this evil (Morrow, 1993). Osig-weh (1989) states that a construct can be delimited through the definition of what it is not. This would allow a better placement of boundaries, favoring a more correct definition and avoid falling into what the author calls "stretching" of constructs. That is, a situation in which the construct overflows its borders and begins to lose its nuclear (or true) meaning. In specific regard to commitment, Osig-weh (1989) points out that it has been "defined in a much too broad way, both as an attitude and as behavior" (p. 582).

Taking into account these conceptual issues, Rodrigues (2009) proposed to separate the affective dimensions of commitment (affective and normative) from the continuance dimension because there is relevant empirical evidence that they display different relations with antecedents and consequents. Such differences indicate that, although both were meant to predict tenure in the organization, continuance commitment and affective commitment are distinct constructs. For example, how could a committed worker present a negative relationship with performance when analyzing the continuance base and a positive one when coming from the affective base (Meyer, Paunonen, Gellatly, Goffin, & Jackson, 1989). According to Osigweh (1989), dimensions of the same construct should present consistent result with regard to its antecedents and consequents.

This study continues the commitment construct revision proposed by Rodrigues (2009) by separating the continuance dimension, which is now referred to as Organizational Entrenchment. It aims to compare the influence of organizational affective commitment and entrenchment on three behavioral intentions towards the organization that Mowday (1998) characterizes as typical of committed people: the intentions to stay in the organization, to exert extra effort in favor of it, and to defend it.

Organizational Commitment

The organizational commitment concept arose from studies that explored the relationship between employees and organizations. It has been defined as a psychological linkage to the organization that stabilizes the behavior (Meyer et al., 1989). The reason for these studies was the belief that committed employees would have greater potential for better performance, reduced absenteeism, and turnover (Mowday, 1998). The first studies conducted were based on single dimension conceptualizations of affective commitment and outcome variables related to the process of leaving the organization, as demonstrated in some meta-analytical works conducted (Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Riketta, 2002). However, Jaros (1997) found that commitment would affect this process indirectly through intention.

The need to use multi-dimensional approaches emerged in order to assess how different forms of commitment would impact organizational context variables in different ways. In 1991, Meyer and Allen presented a paper that became a reference for commitment research, in which the construct was conceptualized as three-dimensional: affective, continuance, and normative commitment. Efforts for measuring this construct resulted in instruments developed by the authors, which significantly contributed to a better clarification of it.

But, the model proposed by Meyer and Allen (1991), despite representing a move towards a better understanding, is far from being a consensus in the area. Conceptually, the normative commitment overlaps with affective commitment. Even Meyer and Allen (1991) stated that "the feelings of wanting to do and feel compelled to do may not be totally independent" (p. 79). However, they pointed out that the effects (consequents) of normative commitment are less strong (or more shortly lived) than those arising from affective commitment.

Mowday (1998) highlighted the issue of overlap between different conceptual models proposed for commitment. The author pointed out that the affective and continuance commitments proposed by Meyer and Allen (1991) respectively overlap with internalization and compliance proposed by O'Reilly and Chatman in 1986. In addition, empirical evidences have shown that continuance commitment has different effects than affective commitment in relation to performance (Meyer et al., 1989).

In this regard, Rodrigues (2009, p. 176) states that being committed is not "to stay out of necessity" or "to continue a course of action by reason of loss of investments, personal sacrifices, or limitation of alternatives". This author proposed that continuance commitment is a different construct, which is called entrenchment and should be separated from the commitment model. There is already empirical evidence that indicate that it is really something, other than commitment (Carson, Carson, & Be-deian, 1995; Rodrigues, 2009; Scheible, Bastos, & Rodrigues, 2007).

Organizational Entrenchment

The concept of entrenchment was initially proposed by Mowday et al. (1982) as the final stage of commitment. For these authors, workers' commitment is dynamic, and changes over time in a job, giving rise to entrenchment. These authors asserted that individuals become entrenched because they reach top positions (and rewards) as they spend more time in the organization. Moreover, the investments made by the employee also accumulate, making it harder for them to leave the organization. Other factors that might entrench individuals are: the loss of social network that they develop in the organization and the reduction of mobility due to the perception of few alternatives in the job market. This perception seems to come from specific knowledge acquired that can be less transferable, or an older age, making entry more difficult in other organizations (Mowday et al., 1982).

The proposition of Mowday et al. was made in 1982, at a different scenario than today. The idea of developing a career in a single organization in the late '70s and early 80's was still strong. But a lot has changed since then, and careers no longer are constrained to the borders of organizations. Given this context, in 1995, Carson et al. (1995) proposed entrenchment as a separate construct focusing on careers, rather than considering it as an evolution of commitment. According to Carson et al. (1995), entrenchment is a process of stagnation in which individuals do not adapt and are not motivated to find other alternatives to their profession. These authors identified three dimensions for this construct: 1) investments (time and / or money) accrued in their careers, 2) emotional costs that would be lost with a career change, 3) lack of alternatives for changing career. The concept of entrenchment is based on the side-bet theory proposed by Becker (1960). Rodrigues (2009) expanded this concept to the organization, saying it may be treated differently from commitment towards the organization as well.

Entrenchment, therefore, is a metaphor that refers to the continuity of professionals in an organization (or career), as changing seems disadvantageous or not feasible. Commitment, on the other hand, is linked to the consistency of action by choice or rejection of other alternatives (Bastos, 1994). Carson and Carson (1997) stated that dissatisfied and entrenched individuals would seek mechanisms to manage stress, such as leaving the organization, verbal confrontation, passive loyalty, or neglect, including absenteeism, increased errors and inefficiency at work. On the other hand, satisfied entrenched professionals would tend to make new investments and to contribute constructively, reducing turnover and increasing the stability of the workforce. In an empirical study, based on their model of career entrenchment, Carson et al. (1995) found that entrenched groups of professionals equally displayed high levels of continuance commitment, low intention of leaving, and greater stability in their careers compared to non-entrenched. Rodrigues (2009) also found overlap between organizational entrenchment and continuance commitment to the organization.

Behavioral Intentions

According to Bratman (1987), the concept of intention has often been reduced to a mixture of desire and belief (or knowledge). However, desire and belief are formulated around a proposition, while an idea is formulated around one action (or a set of actions). The intention of doing something (or perform) is related to the coordination of plans that make possible the execution or accomplishment of the object of intention. Thus, unlike a desire, an intention has three characteristics: (1) it presents problems for individuals, who must determine a way to achieve it; (2) it produces scenarios that make it possible for other ideas to emerge; (3) individuals constantly compare their actions to their intentions. Also, when individuals have an intention, they believe that it is possible, and that they can achieve it.

Whether in social psychology or organizational behavior, behavioral intentions are subject of investigation for two reasons: (1) as an important feature to anticipate possible decisions of individuals and, therefore, be a decisive mediator between conditions and behavior; and (2) as a strategy to approach the behavior of individuals due to the methodological difficulties of having access to actual behaviors. Ajzen and Fishbein (1977) state that behavioral intentions correspond to a subjective probability that an individual will perform a certain behavior. As part of the subjectivity of individuals, attitudes associated with thoughts, feelings, and actions emerge ultimately driving how people behave. According to Menezes (2009), "behavior can be predicted more accurately when investigating behavioral intentions rather than attitudes of individuals" (p. 17).

Thus, when the behavior of individuals within organizations is analyzed, it is important to consider the existence of intentions as a predecessor of behaviors. Since behavior poses methodological challenges, requiring observation and recording of daily occurrences, observation of intentions is presented as a viable alternative to predict the actions of individuals. The use of intentions to predict behavior has been widely applied, especially in a research on turnover. According to Steel and Lounsbury (2009), intentions are nuclear components in the models that analyze turnover. In most models studied, the more the individual is committed to the organization; the individual will have less intention to leave the company, characterizing commitment as a core affective mechanism. To Menezes (2009), the correlations between commitment and turnover are strong when they refer to affective commitment, but there are also significant relationships between turnover and continuance commitment. For that author, the intention to stay within the organization "refers to the willingness to stay in the organization even though different alternatives are perceived as viable" (Menezes, 2009, p. 111). Rodrigues (2009), on the other hand, adds "it is not possible to speak of a voluntary permanence of an entrenched worker, but a continuity in a course of action due to the perception of loss or need" (p. 76).

Another intention of committed behavior is the intention to exert an extra effort on behalf of the organization. Mowday et al. (1982) conceptualize this predisposition (or intention) as one of the cornerstones of commitment, leading to highly committed behavior. Menezes (2009) states that this exercise corresponds to the "extra dedication and commitment of employees towards the organization, as responses to emergency needs of the company, as well as temporary or permanent waiver of the benefits and advantages" (p. 110). According to the study conducted by Mowday et al. (1982), it is expected that highly committed employees are willing to expend a high level of energy in defense of the organization. It means that they would defend the organization against the criticism of others, showing concern for its internal and external image.

Hypothesis

The impacts of organizational commitment and entrenchment on the three behavioral intentions studied were investigated in the following hypotheses:

(1) Hypothesis H1: Affective organizational commitment is a predictor of the intention to stay, to exert an extra effort, and defend the organization.

(2) Hypothesis H2: Organizational entrenchment has no influence over the intention to stay, to exert an extra effort, and defend the organization.

Hypothesis H1 was based on Mowday et al. (1982), since the intentions referred to behavior pointed out by these authors are typical of committed individuals. Hypothesis H2 relies on Menezes (2009), who states that remaining in the organization for lack of alternatives, or due to the belief that leaving it would lead to personal or professional losses, which characterizes entrenchment, is not consistent with committed behavioral intentions.

Method

Sample and Procedures

The survey was conducted in a Brazilian information technology company with nationwide presence. The company allowed access to a group of about 1200 people. People from several Brazilian states participated, totaling 307 respondents, representing more than 25% of the focused group. The questionnaire was applied through a system made available via the Internet from July to September 2009. Questions regarding the central variables were answered on Likert scales with one to six values. The neutral item (neither for, nor against) was not used. The internal consistency of the scales used was tested by calculating the Cronbach's alpha coefficient. Sample normality of all variables was checked through the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The main variables were normally distributed. So, Pearson's correlation analysis was used to evaluate relationships between variables.

The variables that make up the scales of affective commitment and entrenchment were assessed using Factor Analysis with the Common Factors method and Oblimin oblique rotation, as recommended by Fabrigar, Wegener, Maccalum, and Strahan (1999). To verify the sample data fit to the factor model, the Bartlett Sphericity and the Measure of Sampling Adequacy Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) tests were performed, attesting that the factor analysis could be used with success for the sample collected. For the verification of Hypotheses 1 and 2, linear regression analysis was used with the Stepwise method.

Measures

Organizational Affective Commitment. The scale proposed by Bastos, Medeiros et al. (2008) was used to measure affective commitment to the organization. It was chosen because it represents an attempt to find a scale with greater adjustment to the Brazilian context. Another reason for this choice was the fact that it is aligned with the recommendations of Solinger, van Ollfen, and Roe (2008) and defines commitment from an affective and single dimensional approach, reducing the enlarged definition of multidimensional models.

This scale incorporates items from the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) created in 1970 by Porter and Smith, and enhanced in 1979 by Mowday, Steers, and Porter (Mowday et al., 1982). It contains only the affective items removed from the OCQ presented in Mowday et al. (1982), which are exempt from evocations to remain in the organization, as well as items from the Affective Commitment Scale (ACS) of Meyer and Allen (1991) and also the scale proposed by Rego in 2003. So far, this scale has obtained reliability rates higher in Brazilian studies than the original scales previously mentioned (Bastos, Medeiros et al., 2008).

Organizational Entrenchment. The scale proposed by Rodrigues (2009) and Bastos, Rodrigues et al. (2008) was applied to measure organizational entrenchment. This scale represents a proposal for redesigning the organizational commitment construct by treating the continuance base as a separate construct - Entrenchment. As originally defined by its authors, this scale had 22 items distributed in three dimensions: (1) Social Position Adjustments — refers to the investments for adaptation and good performance in the organization; (2) Impersonal Bureaucratic Arrangements — relates to stability and financial gains that would be lost in leaving the organization; (3) Limitation of Alternatives — degree of difficulty to find other viable employment opportunities.

Behavioral Intentions. Behavioral intentions were measured by the Organizational Commitment Behavioral Intentions Scale. According to Menezes (2009), it considers the behavioral intentions as an element of connection between attitudes, beliefs and committed behaviors, representing an attempt to integrate the approach of attitudinal commitment, represented mainly by the work of Meyer and Allen (1991) and Meyer and Herscovitch (2001) with the behavioral approach represented by the studies of Salancik and Kiesler in the 70's. The author reports Cronbach's alphas for the scale ranging from 0.64 to 0.77.

Verification. Bastos, Rodrigues et al. (2008) suggested that future applications of their scale should reevaluate its properties. Thus, factor analysis of the scales chosen was performed to ensure their adequacy, as well as independence of the constructs. The Affective Organizational Commitment Scale demonstrated excellent fit as previous works have shown. The KMO obtained was 0.916, classifying the sample as marvelous. The Bartlett's test confirmed the adequacy of the sample (X2 = 1564.231, df = 45, sig = 0) for the factor analysis. After four iterations, only one factor was obtained. In the Test Set, a chi-square equal to 182.431 with 35 degrees of freedom (df) and significance level = 0 was obtained. These numbers proved that the scale is well suited. The average of all factors was used as the final variable.

Analysis of the Organizational Entrenchment Scale began by examining the main components. The KMO obtained for the scale was 0.847, ranking the sample as meritorious. The Bartlett's test confirmed the adequacy of the sample (X2 = 2115.708, df = 231, sig = 0) for factor analysis. Factor analysis applied to Impersonal Bureaucratic Arrangements dimension of the scale reported the presence of another component and two items were removed, which improved factor loadings for the remaining items. With regard to the Limitation of Alternatives, the factor analysis indicated no refinements for this dimension. In the case of the Social Position Adjustments dimension scale, three items were removed for a better fit. Organizational entrenchment was then calculated from the average of the three dimensions.

Factor analysis was also conducted to ensure independence between affective commitment and organizational entrenchment. The factor loadings obtained confirmed that they are independent constructs. All scales used showed good levels of reliability (above 0.6), as shown in Table 1. The highest reliability index found belonged to the Organizational Affective Commitment scale proposed by Bastos, Medeiros et al. (2008).

Participants

The analysis of personal characteristics of participants reveals a majority of males (68%) and people with operational-level jobs (85%). The sample consists primarily of young people: 29.2% under 25 years, 35.2% are in the range of more than 25 years and less than 30 years, 15.7% have more than 30 and less than 35 years, and the rest is above 35 years (19.7%). Regarding marital status, most people are single (61.8%) and 73% have no dependents. The education level is very high with 25.3% of graduate students, 38.6% with complete college degree, and 19.4% are currently undergrads. The distribution by tenure is balanced: 17.3% have been in the company up to six months; 28.4% more than six to 18 months; 27.1% from 18 to 36 months; and 27.1% over 36 months.

Results

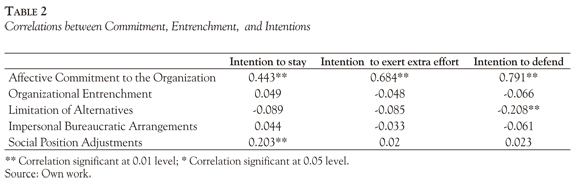

Initially, we sought to establish correlations between the variables studied: affective commitment, entrenchment, and behavioral intentions. Table 2 shows the results obtained. Affective organizational commitment was strongly correlated with all three intentions. The strongest relationship was with the intention to defend the organization. There was no significant correlation between entrenchment and intention.

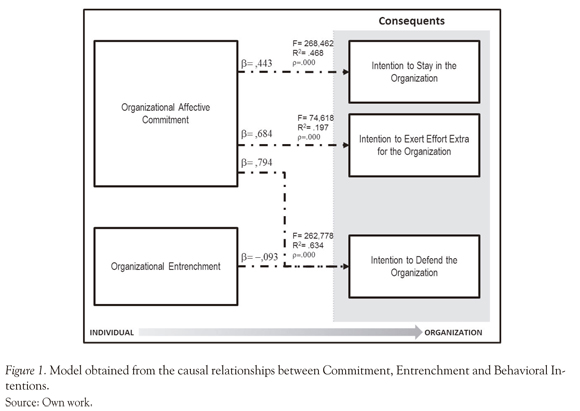

Proceeding with the investigation, hypotheses were tested in relation to the impacts of entrenchment and commitment on the behavioral intentions. Results are shown in Figure 1.

It was found that affective commitment to the organization is a predictor of all the intentions studied, confirming Hyphotesis H1. Entrenchment did not predict the intention to stay or to exert an extra effort. A very weak causal relation was found regarding the intention to defend. So, H2 could not be completely validated. Further investigation is needed to assess this.

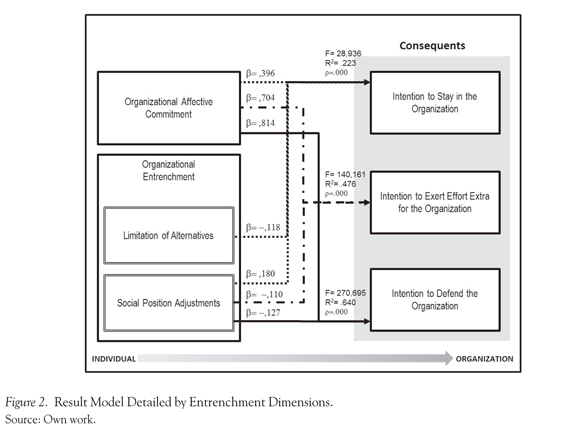

The initial model was then investigated taking into account the three dimensions of entrenchment. The same technique applied earlier was used (linear regression analysis with Stepwise method) and the results obtained are shown in Figure 2.

The intention to stay in the organization has as antecedent factors, in addition to affective commitment (β = 0.396), two dimensions of entrenchment: Limitation of Alternatives (β = -0.118) and Social Position Adjustments (β =0.18). So, there is an ambivalence in the relation of entrenchment with this intention. The Social Position Adjustments dimension positively influences this intention. The Limitation of Alternatives, by contrast, has a negative influence on the intention to stay. When comparing this finding with the result in Figure 1, one can observe that the dimensions of these forces cancel each other out. So, when entrenchment is treated as the sum of its dimensions, no influence appears. The predictive power of commitment in relation to intention to stay is reduced from 46.8% to 22.3%, when coupled with the entrenchment dimensions.

Regarding the intention to exercise extra effort, the dimension Social Position Adjustments also contributes negatively (β = -0.11) as opposed to affective commitment (β = 0.704). However, although opposites, together, they explain more about this intention, raising the coefficient of determination (r2) of 19.7% to 46.7%. The same pattern applies in relation to intention to defend (β = - 127 for Social Position Adjustment and β = 0.814 for the commitment). The coefficient of determination, however, is not materially affected, demonstrating the strength of commitment to this intention. With this detailed analysis, it was possible to better delineate how commitment and entrenchment influence the intentions of behaviors committed in a different way. This contributes to a better characterization of these constructs.

Discussion

The present study explored the relationships between organization affective commitment, entrenchment and behavioral intentions, continuing the work of Bastos, Rodrigues et al. (2008) and Rodrigues (2009), and contributing to a better understanding of how commitment and entrenchment can be used to predict behavior in organizations. As pointed out in a relevant body of literature and evidenced by reviews such as Steel and Lounsbury (2009) and meta-analysis of Cohen (1993), commitment is an important predictor of the intention to stay. Solinger et al. (2008), however, stated that several studies indicate that the continuance commitment should play a stronger role for the permanence of an employee in the organization. These authors also confirm that the affective basis is considered more appropriate to predict permanence.

In this study, positive and significant relationships were found between affective commitment to the organization and the behavioral intentions studied: to remain in the organization, to defend it, and exert extra effort in favor of it. However, no conclusive and relevant relationship was identified between entrenchment and intentions. According to Rodrigues (2009), entrenchment overlaps with continuance commitment. Its own definition is strongly anchored around the need to stay. So, the explanation behind the results found should lie in the distance between intentions and actual behavior. It is possible to infer that the need to stay does not guarantee the intention to stay. It can guarantee the permanence due to the lack of alternatives or a perception of loosing by leaving. Thus, the intention to stay is is much stronger when it is done by volition. This was true as well regarding the other two intentions studied. Contrary to what was hypothesized, entrenchment has proved to be a predictor of intention to defend, albeit with a very low coefficient. This relationship should be investigated further in future works.

In relation to the dimensions of entrenchment, the dimension Social Position Adjustments revealed the best predictive potential, helping to explain the three studied intentions. The Limitation of Alternatives is also a predictor of the intention to stay, while the Impersonal Bureaucratic Arrangements did not appear as a predictor of any intention. The investigation of the dimensions of entrenchment showed a significant negative nature of the relationship between the dimension Limitation of Alternatives and the intention to remain in the organization, while the dimension Social Position Adjustments obtained a positive and significant one. These findings suggest that individuals who perceive gains in social status in the organization want to stay, while people with limited alternatives in the job market stay, but they do not really want to. On the other hand, regarding the intention to exercise extra effort, this dimension contributes negatively, in an opposite direction from commitment.

This study provides further empirical evidence that entrenchment and commitment are distinct constructs by showing that they have different relations with consequents. The results obtained reinforce studies that propose the revision of the construct of commitment, with the separation of the continuance base as operationalized today (Bastos, Rodrigues et al., 2008; Rodrigues, 2009) as different construct called Entrenchment. They also strengthen proposals that recommend returning the commitment construct back to a single dimension design, with only emotional aspects, as advocated by Solinger et al. (2008), Bastos, Medeiros et al. (2008), Bastos, Rodrigues et al. (2008), and Rodrigues (2009). The objective of those proposals is to separate the "want" (like) dimension from the "need" (have to) dimension, outlining commitment with a consistent and positive only aspect through the withdrawal of the dimension that is bringing some negative aspects to it. The present study also supports the importance and quality of affective commitment as a reliable predictor of work outcomes.

There are some limitations in this work that need to be pointed out. One concerns to the profile of respondents, which is very homogeneous with only workers with higher education level. Another is the fact that all are linked to the same organization, setting an illustrative case study. Despite these limitations, this work opens the possibility for further research on organizational commitment and entrenchment. A strength is that it applied and validated measures proposed in the Brazilian context in previous works, allowing the confrontation of results. Future works can evolve from the results obtained and research the relationship of commitment and entrenchment with other antecedents and consequents. Other samples with different professions and education levels could be collected as well, in order to confront the results.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. [ Links ]

Bastos, A. (1994). Múltiplos comprometimentos no trabalho: a estrutura dos vínculos do trabalhador coma organização, a carreira e o sindicato. Doctoral Thesis, University of Brasília, Brazil. [ Links ]

Bastos, A., Medeiros, C., Brito, A., Rodrigues, A., Aguiar, C., & Lisboa, C. (2008, October) Organizational commitment: Enhancing the measure of the affective, continuance, and normative bases for the brazilian work context. Paper presented at the XIII Conferência Internacional de Avaliação Psicológica: Formas e Contextos, Braga, Portugal. [ Links ]

Bastos, A., Rodrigues, A., Aguiar, C., Silva, E., Barreiros, B., & Lisboa, C. (2008, October). Organizational entrenchment: A scale proposal and its factorial validation on brazilian workers. Paper presented at the XIII Conferência Internacional de Avaliação Psicológica: Formas e Contextos, Braga, Portugal. [ Links ]

Becker, H. (1960). Notes on the concept of commitment. American Journal of Sociology, 66(1), 32-40. [ Links ]

Bratman, M. (1987). Intentions, plans and practical reasons. Cambridge: Havard University Press. [ Links ]

Carson, K., & Carson, P. (1997). Career entrenchment: A quiet march towards occupational death? The Academy of Management Executive, 11(1), 62-75. [ Links ]

Carson, K., Carson, P., & Bedeian, A. (1995). Development and construct validation of a career entrenchment measure. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 68(4), 301-320. [ Links ]

Cohen, A. (1993). Organizational commitment and turnover: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 36(5), 1140-1157. [ Links ]

Fabrigar, L., Wegener, D., Maccallum, R., & Strahan, E. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272-299. [ Links ]

Jaros, S. (1997). An assessment of Meyer and Allen's (1991) three-component model of organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 51(3), 319-337. [ Links ]

Mathieu, J., & Zajac, D. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 171-194. [ Links ]

Menezes, I. (2009). Comprometimento organizacional: em busca de um conceito integrador entre as perspectivas atitudinal e comportamental. Doctoral Thesis, Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), Brazil. [ Links ]

Meyer, J., Paunonen, S., Gellatly, I., Goffin, R., & Jackson, D. (1989). Organizational commitment and job performance: It's the nature of the commitment that counts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(1), 152-156. [ Links ]

Meyer, J., & Allen, N. (1991). A three component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61-89. [ Links ]

Meyer, J., & Herscovitch, L. (2001). Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Human Resource Management Review, 11 (3), 299-326. [ Links ]

Morrow, P. (1993). The theory and measurement of work commitment. Greenwich: JAI Press. [ Links ]

Mowday, R. (1998). Reflection on the study and relevance of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 8(4), 387-401. [ Links ]

Mowday, R., Porter, L., & Steers, R. (1982). Employee-organization linkages: The psychology of commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Osigweh, C. (1989). Concept fallibility in organizational science. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 579-594. [ Links ]

Riketta, M. (2002). Attitudinal and organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(3), 257-266. [ Links ]

Rodrigues, A. (2009). From continuance commitment to entrenchment: The proposal and validation of a scale and analysis of the overlap between these constructs. Master Dissertation, Federal University of Bahia, Brazil. [ Links ]

Scheible, A., Bastos, A., & Rodrigues, A. (2007, September). Comprometimento e entrincheiramento: integrar ou reconstruir? Uma exploração das relações entre estes construtos à luz do desempenho. Paper presented at the XXXI Encontro da ANPAD - ENANPAD, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [ Links ]

Solinger, O., van Ollfen, W., & Roe, R. (2008). Beyond the three-component model of organizational commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 70-83. [ Links ]

Steel, R., & Lounsbury, J. (2009). Turnover process models: Review and synthesis of a conceptual literature. Human Resource Management Review, 19(4), 271-282. [ Links ]