Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.13 no.2 Bogotá Apr./June 2014

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-2.ssed

The Social Sharing of Emotions (SSE) in the Dominican Republic's Cultural Context: Autobiographical Descriptive Data*

El Compartir Social de las Emociones (SSE) en el contexto cultural de República Dominicana: datos autobiográficos descriptivos

Nicole Cantisano Jorge**

Université de Toulouse, France

Bernard Rimé

Université de Louvain, Institut de Recherche en Sciences Psychologiques, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium

María T. Muñoz-Sastre

Université de Toulouse II-Le Mirail, Laboratoire Octogone-Cerpp, Toulouse, France

*Artículo de investigación

**Université de Toulouse 2, Le Mirail, URI Octogone-Cerpp, France cantisanonicole@gmail.com

Recibido: octubre 5 de 2013 | Revisado: noviembre 1 de 2013 | Aceptado: diciembre 4 de 2013

Para citar este artículo

Cantisano, N. Cantisano, N., Rimé, B. & Muñoz-Sastre, M.T. (2014). The Social Sharing of Emotions (SSE) in the Dominican republic's cultural context: Autobiographical descriptive data. Universitas Psychologica, 13(2), 457-466. doi:10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-2.ssed

Abstract

The propensity to speak and share emotional experiences, denoted as the social sharing of emotions (SSE), has been thoroughly investigated, showing in different cultural settings that 80% to 95% of emotional experiences, negative or positive, are object of SSE. The present study's main objective was to obtain descriptive data concerning SSE in the Dominican culture. A total of306 Dominican laypersons responded to a questionnaire which recollected autobiographical data aiming: to establish main SSE descriptive indicators (rate, recurrence and delay) and to identify social sharing targets in this cultural context. Findings corroborate previous studies concerning SSE global indicators. First, this Dominican sample is at comparable levels regarding sharing rates 92.48% of emotional episodes were socially shared. Secondly, 68.62% of participants reported having shared the emotional episode the same day it took place. Third, findings revealed that 72.55% of participants talked about the emotion-eliciting event several times. To conclude, the study's findings show that Dominican laypersons are at comparable levels as other populations when it comes to SSE indicators and that Dominicans' choice in social sharing targets, intimates, is compatible with numerous SSE studies (Rimé, 2009).

Keywords: Cognition, Emotions, Social Sharing of Emotions, Dominican Republic

Resumen

La propensión a hablar y compartir experiencias emocionales, denominados como el reparto social de las emociones (SSE), se ha investigado a fondo mostrando en diferentes entornos culturales que el 80% y el 95% de las experiencias emocionales, negativas o positivas, son objeto de la ESS. El objetivo principal de este trabajo fue obtener datos descriptivos relativos SSE en la cultura dominicana. Un total de 306 laicos dominicanos respondieron a un cuestionario autobiográficos que pretendía establecer principales indicadores descriptivos de la ESS (tasa, recurrencia y retardo) y para identificar objetivos sociales para compartir en este contexto cultural. Los hallazgos corroboran los estudios anteriores sobre indicadores globales de SSE . En primer lugar, esta muestra Dominicana se encuentra en niveles comparables con respecto a las tasas de participación en el 92,48% de los episodios emocionales fueron socialmente compartidos. En segundo lugar, 68.62% de los participantes informaron haber compartido el episodio emocional el mismo día en que tuvo lugar. En tercer lugar, los resultados revelaron que 72,55% de los participantes hablaron de la emoción que desencadenaban un evento varias veces. En conclusión, los resultados del estudio muestran que los laicos dominicanos se encuentran en niveles comparables a otros grupos de población en lo que respecta a los indicadores de la ESS y que la elección de los dominicanos en objetivos de reparto sociales, íntimos, es compatible con numerosos estudios de la ESS (Rimé, 2009).

Palabras clave: Cognición, emociones, compartir social de las emociones, Republica Dominicana

Introduction

Many studies have shown that that, following mayor life negative events (e.g. Pennebaker & Harber, 1993; Sydor & Philippot, 1996) as well as daily life events (e.g., Rimé, Finkenauer, Luminet, Zech, & Philippot, 1998), individuals turn towards significant others to share and talk about the emotion-eliciting event (for review see Rimé, 2009). This propensity to speak about emotional experiences has been denoted as the Social Sharing of Emotions ([SSE]; Rimé, 2009; Rimé et al., 1998; Rimé, Mesquita, Philippot, & Boca, 1991; Rimé, Philippot, Boca, & Mesquita, 1992). Evidence shows that succeeding both positive and negative emotional episodes, the SSE is manifested during the hours, days, weeks or sometimes months.

Individuals' tendency to socially share their emotions has been thoroughly studied across ages, gender, socio-educational levels and cultures (Rimé, 2009). Findings suggest that this phenomenon seems to be stable throughout different populations. Studies (Rimé, 2005; Rimé et al., 1991; Rimé et al., 1992; Rimé et al., 1998) show that following an emotional episode, individuals tend to communicate their experience within a short period of time, to intimate others and in a recurrent manner. For instance, when it comes to sharing rates, studies have shown that 80% to 96% of emotional episodes are object of SSE. As to sharing delays, findings demonstrate that the SSE takes place right after the emotional episode (within the same day in 60% of cases). Furthermore, findings show that SSE is a recurrent phenomenon: among 62% to 84% of cases, individuals report having communicated several times about the emotion eliciting event.

Research has been quite interested on cultural effects upon emotion (e.g. Mesquita & Fridja, 1992). For instance, Pennebaker, Rimé and Blankership (1996) tested the hypothesis (initially brought forth by Charles Montesquieu) that habitants from southern and warmer countries are more emotionally expressive than those living in northern countries with colder climates. These authors surveyed individuals from 26 different countries which enabled them to confirm the presence of this stereotype: most participants reported to believe that people from southern countries are much more emotionally expressive than people living in northern countries. Furthermore, authors administered a self-reported questionnaire where participants rated their own emotional expressivity. Results demonstrated a positive correlations (small but significant) between habitants of geographical locations on the south and emotional expressivity. Moreover, results revealed that the average temperature in participants' country of residence was a significant predictor of participants' emotional expressivity.

Studies on cultural effects upon emotion (e.g., Basabe et al., 2000; Mesquita & Fridja, 1992; Pennebaker et al., 1996) could lead to the assumption that cultural differences would exist concerning individuals' propensity to SSE. Yet, research on this matter has failed to evidence a significant effect of culture upon SSE rates. Indeed, social sharing rates were found to be at comparable levels for the different cultures studied (e.g., Mesquita, 1993; Singh-Manoux, 1998; Singh-Manoux & Finkenauer, 2001). However, some cultural differences have been found concerning latency, recurrence and target preferences in the SSE between European cultures and other cultures.

Many studies showed that within different European cultures (e.g. Belgium, France, Holland, Italy, and Spain) social sharing rates were quite similar (Rimé, 2005). Other studies compared SSE rates between collectivist cultures and individualistic cultures. For example, in a study Mesquita (1993) compared the SSE between Dutch participants,

Turkish participants and Surinamese participants. Results showed that, with the exception of shame episodes, Surinamese participants reported lower sharing rates. Moreover, in another study (Rimé, Yogo, & Pennebaker, 1996), SSE characteristics were compared between occidental respondents (France and USA) and Asians respondents (South Korea, Singapour and Japan). Results revealed that sharing rates fluctuated between 80% and 95% among the different cultural groups with the exception of South Korean participants for whom sharing rates were slightly lower. In this study, the highest social sharing rates were found amongst occidental participants. Moreover, some differences were found between occidental and Asiatic participants concerning SSE latency (delay) and recurrence: for occidental groups SSE was plus recurrent and the sharing took place in a shorter delay following the emotional episode when compared to Asiatic participants. In order to explain these observations, Rimé (2005) proposed a plausible argument: such cultural differences could lie upon the individualist/ collectivist continuum brought forth by Hofstede (2003). Indeed, in individualist cultures individuals belong to relational networks highly diversified, and therefore come across a large variety of individuals from their social network. On the opposite side, in collectivist cultures, family is the fundamental basis of relational networks, therefore, social networks are not very diverse and are characterized by symbiotic relationships. Thus, within collectivist cultures, on the one hand, SSE recurrence could be lower due to the fact that social networks are smaller, and on the other hand, emotional episodes are often experienced collectively, for instance, in the company of family members. This would explain the differences in the latency of SSE in collectivist cultures: in order to socially share an emotional episode, one must wait to come upon a member outside of the social network (someone who did not experience the emotional episode as well).

Another important study concerning SSE and intercultural comparisons is that of Singh-Manoux and Finkenauer (2000). SSE was compared among three adolescent groups: Indian adolescents living in New Delhi, adolescents of Indian origin living in London, and British adolescents living in Great Britain. Adolescents' SSE behavior was compared for three emotional episodes: fear, sadness and shame. No difference was found between the three groups was for fear and sadness episodes. As to shame episodes, SSE rates were lower for all groups, thus corroborating previous studies concerning the non-social sharing of shame episodes (for a review see Rimé, 2009). Even though sharing rates were similar for the three groups, differences were found between the three cultural groups concerning the SSE dynamic. For example, in the two oriental groups, SSE recurrence was lower than for participants in the British group. Furthermore, for Indian adolescents, sharing targets were more frequently the initiators of emotional sharing conversations when compared to British adolescents. Another important result from this study is the fact that Indian adolescents choose less frequently parents, grandparents, uncles and aunts as sharing targets when compared to British adolescents. These findings demonstrate that culture could be determinant in social sharing partner preferences within individuals' social network members. For example, collectivist cultures are characterized by psychological distance between individuals and authority figures (Hofstede, 2003). Thus, in collectivist cultures, relationships between adolescents and adults (parents, grandparents) are influenced by obedience and respect.

The series of studies presented above show that the SSE is not exclusive to a cultural group. The SSE is a social aspect of emotional regulation which seems to be quite similar between cultures when it comes to social sharing rates succeeding an emotional episode. Yet, previous research has also shown that the sharing delay, sharing recurrence and sharing targets preferences seem to be influenced by culture.

The present study's main objective was to survey the SSE in the Dominican culture, which is part of Latin-American culture, thus, a collectivist one. Are there cultural specificities concerning the SSE in Dominicans? Through the recollection of descriptive autobiographical data, four main objectives were aimed. First, main SSE indicators (rate, recurrence and delay) were

examined. Along with previous studies (Rimé, 2009), it was expected that: sharing rates would fluctuate between 80% and 96%, participants would share emotional episodes several times and within a brief delay. Secondly, sharing targets were studied. Due to the importance given to family relationships in collectivist cultures, it was hypothesized that family members would be privileged sharing targets by Dominican lay-persons. Furthermore, following previous studies (e.g. Zech & Rimé, 2005), no association between SSE and emotional recovery was expected. Finally, a positive association between the episode's emotional intensity self-reported by participants and SSE indicators was expected. Indeed, previous studies have shown a positive linear correlation between the intensity of emotion elicited by emotional episodes and the extent to which episodes are shared (Rimé, 2009).

Method

Participants

A total of 306 Dominican laypersons took part in this study. Participants were sampled in the Dominican Republic's two mayor cities: Santiago (63.73%, n = 195) and Santo Domingo (36.28%, n = 111). Participants' mean age was 26.26 years (SD = 11.05), ranging from 17 and 82 years; 43.14% (n = 132) were male and 56.86% (n = 174) were female. As to participants' educational level (last level reached), the sample was distributed as follows: 3.59% (n = 11) had reached elementary school, 58.82% (n = 180) finished high school, 15.69% (n = 48) had a technical degree and 21.90% (n = 67) had a university degree. 66.67% (n = 204) of participants were university students, 30.07% (n = 9) were employed full-time and 3.27% (n = 10) had no professional activity.

Procedure

As mentioned above, participants were sampled in the Dominican Republic's two main cities. One single researcher collected the data. Most participants were recruited in university settings (87.58%; N = 268). The study was presented to Professors in different universities, private and public (ex. Economy, Education, Psychology, Law and Engineering Faculties), and following their approval the researcher proposed voluntary participation in the study to students in their classrooms. The same procedure was carried out in an educational structure where adults attend night courses to obtain their high school diploma (3.27%; N = 10). Since a heterogeneous sample was aimed, 9.1% (N = 82) of participants were approached outside the university context. Thus, participation in the study was proposed to individuals in diverse settings (e.g., Beauty Parlors, Hobby Workshops and Private Enterprises).

The part of the sample recruited in the university and educational settings completed questionnaires collectively under the presence of the researcher. For the rest of the sample, questionnaires were administered individually. In both cases, the time length (25 minutes) to complete the questionnaire was announced to participants. All participants who agreed to participate in the study did it voluntarily and without receiving any compensation.

Material

A questionnaire, translated from French (Rimé et al., 1998) to Spanish for the purpose of this study, was administered. This questionnaire aims studying the SSE using autobiographical data. Participants are instructed to recall and briefly describe an emotional experience from their recent past (in the case of this study: within the last three months) corresponding to a specified basic emotion (in the case of this study: a negative emotion). Then, participants are invited to answer questions about their sharing of this episode with other people. First, a French-Spanish back translation was tested in a previous pilot study ( N = 34) to assure item comprehension and adaptation within the Dominican cultural context. The questionnaire's content will be detailed in the following lines.

Emotional Episode: Type of Episode, Time since the Episode and Initial Emotional Impact At first, participants were asked to describe in a few lines a specific episode that they had personally experienced within the last three months and that had elicited a negative emotion. Then, a categorical item assessed the time elapsed since the episode. Respondents evaluated the episode's initial emotional intensity (felt at the time of the episode) using a 10 point likert-scale (0 = no emotion at all; 10 = the most intense emotion).

Emotional Appraisal

Six items assessed participants' emotional appraisal at the time of the episode. Had the episode been: pleasant, unpleasant, controllable, incontrollable, predictable, unpredictable? Respondents evaluated these items using a 6-point Likert scale (0 = not at all; 6 = extremely).

Episode's Current Impact: Consequences, Emotional Impact and Emotional Valence

Five items, to be evaluated upon a 6-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 6 = extremely), assessed the current consequences of the episode for participants: (1) physical, (2) material, (3) social, (4) professional and (5) psychological. Three items (α = 0.77) assessed the episode's current emotional impact (at the time of the study). These items were to be rated upon a 10-point likert scale (0 = not at all, 10 = extremely) and specifically evaluated: (1) the emotional intensity, (2) the mental images elicited by episode memories and (3) body sensations elicited by episode memories. A total score (current emotional impact) ranging from 0 to 30 was obtained through the sum of these three items. As to emotional valence, two items to be rated upon a 6-point Likert scale (0 = not at all; 6 = extremely), assessed respondents' evaluation of the episode at the time of the study: was the episode perceived as pleasant or unpleasant?

Initial SSE and Current SSE

Four items were proposed to respondents in order to examine initial SSE (at the time of the episode): (1) desire to share the episode (6-point likert scale; 0 = not at all, 6 = extremely), (2) delay in sharing (categorical responses), (3) sharing frequency (categorical responses) and (4) number of sharing partners. SSE desire, SSE frequency and number of sharing partners were summed in a total score (α = 0.74) ranging from 2 to 21 thus representing the initial extent of sharing.

As to current SSE (at the time of the study), three items assessed the desire to share (6-point likert scale; 0 = not at all, 6 = extremely), the frequency of sharing (categorical responses) and the number of sharing partners (categorical responses) during the week that the study took place. These three items (α = 0.7) were summed in a current extent of sharing score ranging from 2 to 21.

Current SSE valence was evaluated through a 6-point Likert scale item (0 = very unpleasant, 6 = very pleasant) assessing whether talking about the emotional episode at the time of the study was perceived unpleasantly or not by participants. Moreover, general completeness of SSE was evaluated through three items to be rated upon a 6-point likert scale (0 = not at all, 6 = extremely): (1) average length of conversations, (2) extensiveness of details during sharing conversations and (3) the degree of emotional content during conversations. These three items (α = 0.82) were summed in a general completeness of sharing score ranging from 0 to 18.

SSE Targets

The questionnaire evaluated three aspects of sharing targets: number of sharing targets (categorical response), the first sharing target (categorical response) and SSE initiators (dichotomous response).

Emotional Recovery

Emotional recovery was assessed through one item to be rated upon a 6-point likert scale (0 = much worst, 6 = much better): participants estimated the current emotional impact of the episode compared to the initial impact.

Results

Descriptive Results

Emotional Episode: Type of Episode, Time since the Episode and Initial Impact

Among the 306 episodes reported by respondents 48.69% (n = 149) corresponded to episodes of sadness, 18.95% (n = 58) corresponded to episodes of fear and 32.35% (n = 99) corresponded to anger episodes. As to time since the episode, for 21.90% (n = 67) of participants the episode occurred three months preceding the study, for 65.68% (n = 201) of participants the episode had occurred between three to eleven weeks preceding the study, and for 12.09% ( n = 37) of participants the episode had occurred less than one week preceding the study. Respondents' mean evaluation of the episode's initial emotional intensity was 6.9 (SD = 2.21; N = 306; Range 0-10).

Emotional Appraisal

Mean scores (ranging from 0 to 6) for the six emotional appraisal items were : (1) 0.25 (SD = 0.95) for the pleasant item, (2) 2.31 (SD = 1.88) for the controllable item, (3) 2.16 (SD = 1.98) for the predictable item, (4) 5.01 (SD = 1.32) for the unpleasant item, (5) 3.04 (SD = 2.11) for the incontrollable item and (6) 2.96 (SD = 2.29) for the unpredictable item.

Episode's Current Impact: Consequences, Emotional Impact and Emotional Valence

Mean scores (range 0 to 6) for the episode's consequences assessed were: (1) 0.65 (SD = 1.45) for physical consequences, (2) 1.02 (SD = 1.02) for material consequences, (3) 1.05 (SD = 1.79) for social consequences, (4) 1.81 (SD = 1.95) for professional consequences and (5) 3.12 (SD = 1.94) for psychological consequences.

The current emotional impact mean score (ranging from 0 to 30) was 14.99 (SD = 7.04).

As to emotional valence the mean scores (ranging from 0 to 6) were 0.37 (SD = 1.06) for the pleasant item and 4.41 (SD = 1.59) for the unpleasant item.

Initial SSE and Current SSE

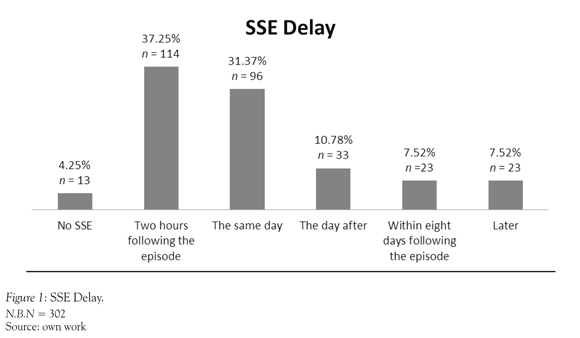

Within the 306 emotional episodes reported by participants, 92.48% (n = 283) were socially shared. In 68.62% (n = 210) of cases, SSE took place the same day the episode happened. Percentages for participants' sharing delay are displayed on Figure 1.

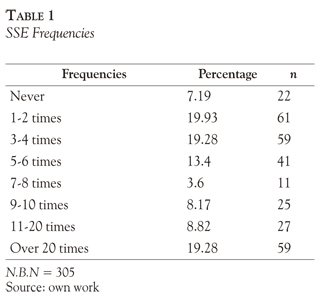

As to participants' desire to share the emotional episode, the sample's mean score on this item was 3.79 (SD = 2.11). SSE frequencies are displayed on Table 1. The sample's mean score (ranging from 2 to 24) concerning Initial extent of Sharing (desire, frequency and number of sharing partners) was 12.94 (SD = 5.31).

Moreover, the sample's mean score (ranging from 2 to 21) concerning Current extent of Sharing (desire, frequency and number of sharing partners) was 6.57 (SD = 4.3). Participants' mean score (ranging from 0 to 6) on the current SSE valence item was 2.66 (SD = 1.52). Finally, participants' mean score (ranging from 0 to 18) concerning general completeness of sharing was 10.99 (SD = 5.36).

SSE Targets

Concerning number of sharing partners, 55.88% (n = 171) of participants declared having spoken about the emotional episode with at least five different persons, 35.29% (n = 108) of participants reported that they had spoken about the episode with more than 6 different persons, and 8.5% (n = 26) of participants reported that they did not speak about the episode at all. As to the first sharing target (the first person to whom they had spoken about the emotional episode), 28.97% (n = 84) of respondents reported having spoken to a first degree family member (mother, father, sister, brother, daughter or son), 25.17% (n = 73) reported having spoken to a friend, 24.14% (n = 70) reported having spoken to their spouse (husband/wife, girlfriend/ boyfriend), 2.76% (n = 8) reported having spoken to another family member (e.g., cousins, aunts), 11.03% reported having spoken to other members of their social networks (e.g., colleagues, episode witnesses, health professional) and the remaining 7.93% (n = 23) of participants had not spoken about the emotional episode.

As to SSE initiators, 60.07% (n = 193) of participants reported having usually initiated conversations themselves. Whereas 34.31% (n = 105) of participants reported that conversations were usually initiated by their targets.

Emotional Recovery

The sample's mean score (ranging from 0 to 6) concerning the item assessing emotional recovery was 4.25 (SD = 1.54). Furthermore, an emotional recovery index was calculated by subtracting participants' self-reported emotional intensity at the time of the study (M = 5.13, SD = 2.6) from participants' self-reported emotional intensity following the episode (M = 6.92, SD = 2.21). The sample's mean score in this emotional recovery index was 1.79 (SD = 2.48).

Correlational Analyses

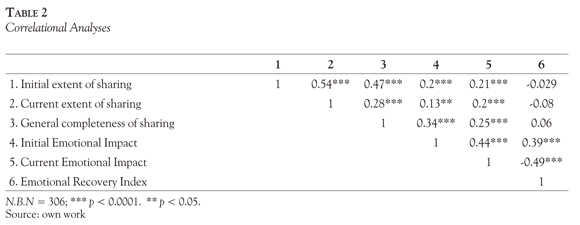

Correlational analyses were conducted in order to examine the relationships between different SSE indicators (e.g. initial and current extent of sharing), the episode's emotional impact and emotional recovery. These results are displayed on the correlation matrix presented on Table 2.

All three SSE indicators (initial and current extent of sharing, exhaustiveness) were significantly positively inter-correlated. Initial extent of sharing was significantly positively correlated to the initial emotional impact (r = 0.2; p < 0.0001) as well as the current emotional impact (r = 0.21; p < 0.0001). Current extent of sharing showed significant positive correlations with the initial emotional impact (r = 0.13; p < 0.05) as well as the current emotional impact (r = 0.2; p < 0.0001). As to general completeness of sharing, positive significant correlations were found between this variable and the initial emotional impact (r = 0.34; p < 0.0001) as well as the current emotional impact (r = 0.25; p < 0.0001). Finally, the emotional recovery index did not show any significant correlations with any of the SSE indicators (initial and current extent of sharing, general completeness of sharing).

Discussion

The present study's main objective was to obtain descriptive data concerning SSE in the Dominican culture. First, we aimed to establish main SSE indicators (rate, recurrence and delay) and to identify social sharing targets in this cultural context. Moreover, emotional recovery and its link to SSE were examined. Finally, the relationship between SSE indicators and the episode's emotional impact were studied.

Findings corroborate our hypothesis concerning SSE global indicators. First, this Dominican sample is at comparable levels regarding sharing rates: 92.48% of emotional episodes were socially shared. Secondly, 68.62% of participants reported having shared the emotional episode the same day it took place. Third, findings revealed that 72.55% of participants talked about the emotion-eliciting event several times. Previous studies using auto-biographical data reported by Rimé (2009) show that sharing rates fluctuate between 80% and 96%, that in 60% of cases individuals report having spoken about the emotion-eliciting event the same day it occurred and that 62% to 84% of individuals report having spoken about the emotional episode several times. Thus, our findings regarding this sample show that Dominican laypersons are at comparable levels as other cultural samples when it comes to SSE rates, delay and recurrence (Rimé, 2005, 2009).

As to sharing targets, results show that most of the time, participants were imitators during sharing conversations. Furthermore, findings revealed that among this sample the first sharing partner choice was predominantly amongst first degree family members (parents, siblings, son, and daughter), a friend or spouse. Findings partially support our hypothesis concerning sharing targets: we expected that family members would be privileged sharing targets in this cultural context. Yet, our descriptive results reveal that friends are important sharing targets within this Dominican sample. Participants' age can be a plausible explanation concerning sharing targets preferences in this sample. Indeed, the sample was mainly composed by young adults (48.37% aged between 17 and 22 years old). Our findings corroborate a previous study (Rimé, Charlet, & Nils, 2004) which demonstrated that among adolescents and young adults, aged between 16 and 20 years old, friends constitute important sharing targets.

Moreover, one of the present study's main interests was to examine the relationship between SSE indicators and emotional recovery. Along with previous research (e.g., Finkenauer & Rimé, 1998; Zech & Rimé, 2005; Nils & Rimé, 2012) no association between SSE and emotional recovery was expected. Our findings corroborate previous ones: no significant correlations were found between extent of sharing (initial and current) and emotional recovery.

Both initial and current extents of sharing were positively significantly correlated to the episode's emotional impact self-reported by respondents. Thus, findings confirm the hypothesis concerning the associations between emotional intensity and SSE. Indeed, previous studies, including experimental studies (Rimé, 2009), suggest that in order for SSE to be triggered a minimal emotional intensity threshold must be reached.

One of the present's study limitations is the sample's mean age (mainly young adults) which does not allow undertaking comparisons between different age groups. Furthermore, gender comparisons were not possible because significant differences were found between male and female participants regarding self-reported emotional intensity: women reported greater emotional intensity following the episode. Thus, future studies should aim comparing different SSE aspects (for instance target preferences) between different ages and gender in the Dominican culture.

To conclude, this study's findings show that Dominican laypersons are at comparable levels as other populations when it comes to SSE indicators: rates, delay and recurrence. Dominicans' choice in social sharing targets, intimates, is compatible with numerous SSE studies (Rimé, 2009). Moreover, within this cultural context, as well as in other ones, no associations were found between SSE and emotional recovery. Finally, these findings evidence the positive association between emotional intensity elicited by the event and SSE.

References

Basabe, N., Rimé, B., Paez, D., Pennebaker, J. W., Valencia, J. F., Diener, E., & González, J. L. (2000). Sociocultural factors predicting subjective experience of emotion: A collective level analysis. Psicothema, 12(Suppl. 1), 55-69. [ Links ]

Finkenauer, C., & Rimé, B. (1998). Socially shared emotional experiences vs. emotional experiences kept secret: Differential characteristics and consequences. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 17(3), 295-318. [ Links ]

Hofstede, G. (2003). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. London: Profile Books LTD. [ Links ]

Mesquita, B. (1993). Cultural variations in emotion: A comparative study of Dutch, Surinamese and Turkish people in the Netherlands. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [ Links ]

Mesquita, B., & Frijda, N. H. (1992). Cultural variations in emotions: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 112(2), 179-204. [ Links ]

Nils, F., & Rimé, B. (2012). Beyond the myth of venting: Social sharing modes determine emotional and social benefits from distress disclosure. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(6), 672-681. [ Links ]

Pennebaker, J. W., & Harber, K. (1993). A social stage model of collective coping: The Loma Prieta earthquake and Persian Gulf war. Journal of Social Issues, 49(4), 125-145. [ Links ]

Pennebaker, J. W., Rimé, B., & Blankenship, V. E. (1996). Stereotypes of emotional expressiveness of northerners and southerners: A cross-cultural test of Montesquieu's hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 372-380. [ Links ]

Rimé, B. (2005). Le partage social des émotions. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [ Links ]

Rimé, B. (2009). Emotion elicits the social sharing of emotion: Theory and empirical review. Emotion Review, 1(1), 60-85. [ Links ]

Rimé, B., Charlet, V., & Nils, F. (2004). Partners for the social sharing of emotion. University of Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium. Unpublished Manuscript. [ Links ]

Rimé, B., Finkenauer, C., Luminet, O., Zech, E., & Philippot, P. (1998). Social sharing of emotion: New evidence and new questions. European Review of Social Psychology, 9(1), 145-189. [ Links ]

Rimé, B., Mesquita, B., Philippot, P., & Boca, S. (1991). Beyond the emotional event: Six studies on the social sharing of emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 5(5-6), 435-465. [ Links ]

Rimé, B., Philippot, P., Boca, S., & Mesquita, B. (1992). Long lasting cognitive and social consequences of emotion: Social sharing and rumination. European Review of Social Psychology, 3(1), 225-258. [ Links ]

Rimé, B., Yogo, M., & Pennebaker, J. W. (1996). [Social sharing of emotion across cultures]. Unpublished raw data. [ Links ]

Singh-Manoux, A. (1998). Partage social des émotions et comportements adaptatifs des adolescents: une perspective interculturelle. Unpublished Doctoral Disertation, Universtité de Paris X, Nanterre, France. [ Links ]

Singh-Manoux, A., & Finkenauer, C. (2001). Cultural variations in social sharing of emotions: An intercultural perspective on a universal phenomenon. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(6), 647-661. [ Links ]

Sydor, G., & Philippot, P. (1996). Conséquences psychologiques des massacres de 1994 au Rwanda. Santé Mentale au Québec, 21(1), 229-248. [ Links ]

Zech, E., & Rimé, B. (2005). Is talking about an emotional experience helpful? Effects on emotional recovery and perceived benefits. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 12(4), 270-287. [ Links ]