Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Universitas Psychologica

versão impressa ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.13 no.2 Bogotá abr./jun. 2014

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-2.rwas

Right Wing Autoritharism, Social Dominance Orientation, Controllability of the Weight and their Relationship with Antifat Attitudes*

Autoritarismo, orientación a la dominancia social, controlabilidad del peso y su relación con las actitudes antiobesos

Alejandro Magallares**

Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, Madrid, España

*Artículo de investigación

**Departamento de Psicología Social y de las Organizaciones. Facultad de Psicología UNED. C/Juan del Rosal, 10. 28040, Madrid. E-mail: amagallares@psi.uned.es

Recibido: septiembre 13 de 2011 | Revisado: mayo 1 de 2012 | Aceptado: febrero 26 de 2013

Para citar este artículo

Magallares, A. (2014). Right wing autoritharism, social dominance orientation, controllability of the weight and their relationship with antifat attitudes. Universitas Psychologica, 13(2), 771-779. doi:10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-2. rwas

Abstract

Antifat attitudes (AFA) refer to stereotyping based on people's weight. Literature suggests that people who have an ideologically conservative outlook on life also report negative attitudes toward obese people. Also, it is well established that one of the roots of AFA is the perception that prejudiced individuals have about the controllability of the weight. Therefore, in the current study it is analyzed if Right Wing Autoritharism (RWA, predisposition that individuals have to follow the dictates of a strong leader and traditional and conventional values) and Social Dominance Orientation (SDO, the desire that one's ingroup dominates other outgroups) predicts prejudice toward obese people and if controllability of the weight mediates this relationship. 456 female students of the UNED (Spanish Open University) from 18 to 35 years were part of the final sample of the study. Results showed that RWA, SDO, controllability and AFA were positively correlated and that the relationship between RWA, SDO and AFA was mediated by the controllability of the weight.

Keywords: Right wing autoritharism, social dominance orientation, antifat attitudes, controllability.

Resumen

Las actitudes antiobesos hacen referencia a los estereotipos sobre las personas con problemas de peso. La literatura sugiere que la gente que tiene una visión ideológica conservadora también presenta actitudes negativas hacia las personas obesas. Es un hecho bien establecido que una de las raíces de las actitudes negativas hacia los obesos es la percepción que tienen las personas prejuiciosas sobre la controlabilidad del peso. En el presente estudio se ha analizado si el autoritarismo (predisposición que tienen los individuos a seguir los dictados de un líder así como a tener valores convencionales y tradicionales) y la orientación a la dominancia social (el deseo de que el endogrupo domine al resto de exogrupos) predice el prejuicio hacia las personas obesas y si la controlabilidad del peso media esta relación. Para ello, se seleccionaron 456 mujeres estudiantes de la Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED) de 18 a 35 años. Los resultados pusieron de manifiesto que el autoritarismo, la orientación a la dominancia social, la controlabilidad del peso y las actitudes antiobesos estaban positivamente correlacionadas, y que la controlabilidad mediaba la relación entre las variables ideológicas y la actitud antiobesos.

Palabras clave: Actitud antiobesos, autoritarismo, orientación a la dominancia social, controlabilidad del peso.

Introduction

Obesity is a medical condition in which excess body fat produces a negative effect on health, reduces life expectancy and increases the likelihood of several illnesses, among others, heart disease, breathing difficulties during sleep, type 2 diabetes, certain types of cancer and osteoarthritis (Haslam & James, 2005). Its steadily increasing prevalence rate in Western industrialized countries (World Health Organization [WHO], 2000) has been paralleled by an ever stronger social rejection and exclusion of obese people, who nowadays are exposed to a full array of discriminatory and stigmatizing experiences of many kinds in largely unfavourable societal contexts (Puhl & Heuer, 2009). Several studies prove that being fat generates rejection and discrimination problems in healthcare settings (see for example, Hebl & Xu, 2001), in the school (see, Hayde-Wade et al., 2005), in interpersonal relationships (Falkner et al., 2001) or in the workplace (Roehling, Roehling, & Pichler, 2007). Antifat attitudes (AFA) refer to stereotyping based on people's weight (Crandall, 1994). Common weight-based stereotypes are, for example, that obese people are lazy, that they do not have self-discipline, that they have poor willpower, that they are less intelligent and that they have flaws in their character. It has been found that people who have an ideologically conservative outlook on life also report negative attitudes toward obese people (Crandall & Biernat, 1990, Study 1) and that the perceptions about the causes of overweight (usually, blaming obese people of their weight) are partially responsible for the AFA (DeJong, 1980, 1993). For this reason, in the current research it will be studied why obese people are stigmatized, analyzing the ideological and attributional roots of the prejudice toward obese individuals.

Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, and Sanford (1950) described what they called the authoritarian personality. Adorno et al. (1950) argued that this construct measured, with the F scale, the predisposition that individuals have to follow the dictates of a strong leader and traditional and conventional values. According to Adorno et al. (1950) the authoritarian personality was a major determinant of generalized prejudice in people toward different groups. Altemeyer (1981, 1988) criticized the F scale for its psychometric properties and for this reason developed the Right Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) scale to remedy these deficiencies, but maintaining the main characteristics identified by Adorno et al. (1950). Research with the RWA have showed again that individuals with high scores in this scale reported more negative attitudes to different outgroups, minorities, and other stigmatized social groups (see for example, Van Hiel & Mervielde, 2005). In the case of the obese group, Crandall and Biernat (1990, Study 2) found that RWA was substantially correlated with AFA. More recently, Miller and Lundgren (2010) and Holub, Tan, and Patel (2011) have found similar results. It is important to remark that one study (Blass, 1995) has shown that RWA is related to the tendency to blame victims for the punishment they receive, which can be very important to explain why people high in RWA report AFA (because obese people are seen responsible of their weight). Therefore, this result suggests that the perception that people have personal control of their own problems is related to RWA. For this reason, one of the main aims of the current study is to analyze if RWA is related to AFA and specially the link that this ideological variable has with the perception of controllability of weight.

Sidanius and Pratto (1993) and Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, and Malle (1994) proposed an alternative to the RWA theory, with the Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) theory. Pratto et al. (1994) described SDO as a 'general attitudinal orientation toward intergroup relations, reflecting whether one generally prefers such relations to be equal, versus hierarchical' and the 'extent to which one desires that one's ingroup dominate and be superior to outgroups' (p. 742). Again, Pratto et al. (1994), with their SDO scale, found that this construct was also strongly associated with generally prejudiced and ethnocentric attitudes towards minorities and stigmatized outgroups like the RWA scale (see also, Van Hiel & Mervielde, 2005). In the case of obese people, just an investigation has found that participants with higher SDO scores reported also more implicit AFA (O'Brien, Hunter, & Banks, 2007). Again, it was found that individuals who reported high scores on the SDO scale were more inclined to blame victims (see, Pratto et al., 1994; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). This result suggests that SDO is related with the tendency to assume that negative outcomes are under personal control which may be related to AFA though there are not researches about this topic. For this reason, in the current research it will be studied if SDO is related to AFA (in this case with explicit measures) and if this ideological variable has a relationship with the controllability of weight.

Research suggests that beliefs about the causality and stability of overweight are important factors contributing to AFA (Crandall, 1994). One of the first studies conducted to demonstrate that the attributions of controllability were related to AFA was made by DeJong (1980). This author showed that when obese people could offer an excuse for their weight (such as a glandular disorder) they were given a more positive evaluation. In another experiment, DeJong (1993) found that their participants rated obese people as more self-indulgent and less self-disciplined than normal-weight people, except when the obesity was said to have resulted from a glandular disorder. Hansson and Rasmussen (2010) have shown more recently that one of the predictors of obesity stereotypes were parents' beliefs about controllability of weight. As a matter of fact, O'Brien, Puhl, Latner, and Hunter (2010)

have proved that AFA can be reduced or exacerbated depending on the causal information provided about obesity to their participants. As we have seen, some ideological variables (like RWA and SDO) are related to a strong faith in the personal responsibility that people have for their negative's outcomes (Skitka, Mullen, Griffin, Hutchinson, & Chamberlin, 2002). However, there are not studies that analyze the relationship between RWA, SDO and the perception of the controllability to explain the prejudice toward obese people. According to the reviewed literature, it seems that the perception of controllability can be mediating the effects between ideological variables (like RWA and SDO) and AFA. To summarize, the goals of the current study are to analyze if RWA, SDO, controllability of weight and AFA are related. According to the reviewed literature, the first hypothesis is that RWA, SDO and controllability of weight will have a positive and direct correlation with AFA. Additionally, it is expected, as the second hypothesis of the study, that RWA and SDO will have a positive and direct correlation with AFA but that controllability of weight will mediate this relationship.

Method

Participants were 456 female students of the UNED (Spanish Open University) from 18 to 35 years (age: M = 25.1, SD = 3.62; Body Mass Index or BMI: M = 21.86, SD = 2.78) who were enrolled in a psychology course and who received extra credit for their participation.

To measure anti-fat attitudes we used the Spanish versions of the Antifat Attitudes Questionnaire (AFA) (English version: Crandall, 1994; Spanish version: Magallares & Morales, 2008). The AFA evaluates attitudes toward overweight and obese individuals. AFA (α = .72) consists of 7 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Higher scores on the AFA scale reflect greater dislike toward obese people.

To measure the controllability of the weight the Beliefs about Obese Persons Scale (BAOP) (English and Spanish versions: Allison, Basile, & Yuker, 1991) was used. BAOP measures beliefs about the causes of obesity with an eight-item Likert rating scale (from 1, strongly disagree, to 7, strongly agreed). Coefficient alpha was 0.71. A score was computed by averaging the 8 items of the scale. Higher scores on this measure reflect greater beliefs that obesity is under personal control.

Right-wing authoritarianism was measured by the RWA scale (English version: Altemeyer, 1981, 1988. Spanish version: Seoane & Garzon, 1992). The RWA scale is a 30-item scale with 15 items worded in an authoritarian manner, and 15 items in a nonauthoritarian direction. Respondents answered on 7-point scale ranging from 1 strongly agree to 7 strongly disagree, with a 4 dont know central point. The reliability of the scale was good (α = 0.83). A score was computed by averaging the 30 items of the scale. Higher scores on this measure reflect a greater predisposition to follow the dictates of a strong leader and traditional and conventional values.

To measure Social Dominance Orientation we used the SDO scale (English version: Pratto et al., 1994; Spanish version: Silván-Ferrero & Bustillos, 2007). A 7-point Likert scale was used for each of the 14 items. Participants rated their agreement or disagreement with statements from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 ( strongly agree). Coefficient alpha was 0.82. A score was computed by averaging the 16 items of the scale. Higher scores on this measure reflect greater preference for hierarchical relations.

Results

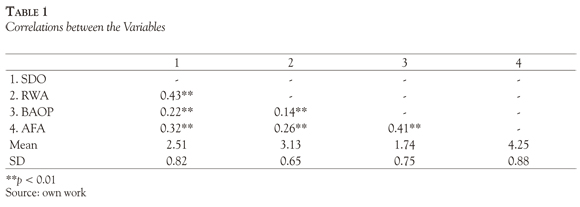

First of all, Pearsons correlations were made in order to see the relationships between the variables of the current study. Table 1 shows, like the first hypothesis said, a positive correlation between the ideological variables (RWA and SDO) and negative attitudes toward obese people (AFA) and controllability of the weight (measured with BAOP).

Prior to conducting the regression analyses, and in order to avoid potential problems with overlap between variables, multicollinearity tests were conducted. Since all the tolerance indices were greater than 1 - R2, none of the variables had to be removed or aggregated in the analyses.

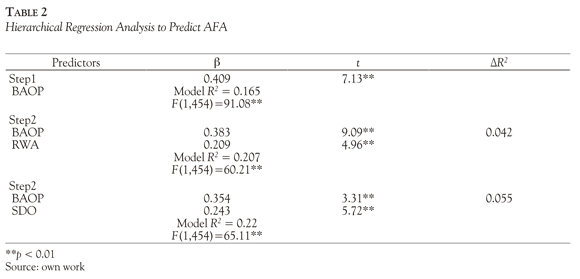

To test if controllability of weight was a mediating variable linking ideological variables (RWA and SDO) to negative attitudes toward obese people (AFA), procedures outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986) were followed. According to these authors, the first step in testing for mediation is to check for statistically significant association between the independent and dependent variables. In this investigation, the ideological variables (RWA and SDO) are the independent variables, and as we saw before (Table 1) they had a statistically significant association with AFA (dependent variable). Baron and Kenny (1986) say that the next step is to establish a statistically significant association between the independent variables and the mediator. In Table 1 it can be seen that RWA and SDO were also statistically significant associated with controllability of weight (BAOP). Finally, Baron and Kenny (1986) argue that the final step is to determine if the inclusion of controllability of weight as a mediator decreases the relation between the independent and dependent variables. To this end, two regression analyses were conducted (one for RWA and the other one for SDO), entering controllability of weight into the equation on Step 1, and ideological variables on Step 2. Therefore, the mediating role of controllability of weight would be tested if on Step 2 beta of controllability is statistically significant and the beta of the independent variable is less than those correlations which were found between each of independent variables and the dependent variable (AFA). In the case of true mediation, the association between different ideological variables (RWA and SDO) and AFA would be reduced to zero and in partial mediation just a decrease of the association accompanies the inclusion of controllability of weight in the model. The results of these two regression analyses can be seen in Table 2.

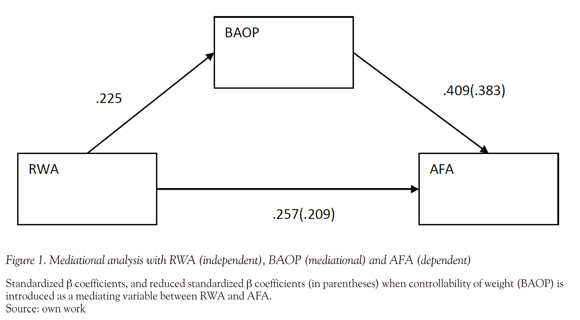

According to these regression analyses, it can be said that the relationships between RWA (see Figure 1) and SDO (see Figure 2), on the one hand, and AFA, on the other hand, were mediated by controllability of weight as it was hypothesized. Associations between these independent and dependent variables were reduced, but nonzero, indicating that controllability of weight is a partial mediator.

To test if the reduction in the relationship between the independent (RWA and SDO) and dependent variables (AFA) is significant, when the mediating variable (BAOP) is included in the regression model, the procedure outlined by Sobel (1988) was followed. Sobel tests were 2.59 (p < 0.01), for RWA, and 4.41 for SDO (p < 0.001), indicating that the relationships between RWA and SDO, on the one hand, and AFA, on the other hand, were significantly reduced with the inclusion of controllability of weight as a mediator.

Also, the procedure proposed by Holmbeck (2002) was followed to determine the percentage reduction in a bivariate association when the mediator is taken into account. It was found that the magnitudes of the relationships between RWA and SDO, on the one hand, and AFA, on the other hand, were reduced to 81.32 and 75.23% respectively when controllability of weight (BAOP) was included as a mediating variable.

Discussion

According to the results of the current study, ideological variables (RWA and SDO) and attributional (controllability of weight) are related to AFA. Some studies prove that the RWA and SDO scales together account for a significant proportion of the variance in prejudice toward different out-groups with no other variables adding anything to variance predicted (Ekehammer, Akrami, Gylje, & Zakrision, 2004; Roets, Van Hiel, & Cornelis, 2006). However, in the case of AFA, the controllability of weight helps to explain why people high in RWA and SDO report negative attitudes toward obese people. According to the results, the nature of the relationship between ideological variables and AFA is not direct, because controllability of weight mediates the relationship between RWA and SDO, on the one hand, and AFA, on the other hand. This result suggests that people with a conservative ideology report negative attitudes toward obese people, especially when they blame overweight individuals of the excessive weight they have. For example, Crandall and Martinez (1996) have found that Mexican students were significantly less concerned about their own weight and more accepting of obese people than were U.S. students, because the perception of controllability of the weight was much higher in U.S. sample. Therefore, besides the importance of the ideology to explain prejudice toward different outgroups, in the case of obesity it is necessary, in addition, to study the attributions of controllability.

The results of the current research prove the importance of the controllability of weight is crucial to explain why people have AFA. It is important to remark that even obese people are also likely to see their condition as controllable and for this reason to blame themselves of their excessive weight (Blaine & Williams, 2004). Although the strength of AFA decreases as people' BMI increase, AFA can even be found in obese samples (Schwartz, Vartanian, Nosek, & Brownell, 2006). For this reason, future research should be done in order to analyze how ideological and atributtional variables interact with overweight participants.

Although epidemiological studies have shown the increasing prevalence of obesity (Caballero, 2007), this social phenomenon, unfortunately, has not attenuated AFA in Western industrialized countries. For this reason, the knowledge that controllability of weight plays a major role in AFA should be applied to develop stigma-reduction strategies to reduce stereotypes about obese people (Daníelsdóttir, O'Brien, & Ciao, 2010).

It is important to remark that AFA can produce a big impact on the life of the person who suffers discrimination or exclusion because of their weight. For example, some investigations have showed that AFA do not help obese people to have a healthy life. For example, it has been proved that individuals who experience weight-based stigmatization engage in more frequent binge eating (Ashmore, Friedman, Reichmann, & Musante, 2008), are more likely to avoid exercise (Vartanian & Shaprow, 2008) and that discrimination experiences were associated with greater caloric intake and lower energy expenditure (Carels et al., 2009). In addition, AFA are related with less well-being and a poorer physical health. As a matter of fact, weight stigmatization is an important risk factor to develop depression (Jackson, Grilo, & Masheb, 2000), low self-esteem (Carr & Friedman, 2005) and body dissatisfaction (Wardle, Waller, & Fox, 2002). Therefore, AFA should be eradicated of society because they do not help obese people to lose weight and in addition affect their quality of life.

References

Adorno, T., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D., & Sanford, N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York: Harper. [ Links ]

Allison, D. B., Basile, V. C., & Yuker, Y. E. (1991). The measurement of attitudes toward and beliefs about obese persons. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 10(5), 599-607. [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1981). Right-wing authoritarianism. Winnipeg, Canada: University of Manitoba. [ Links ]

Altemeyer, B. (1988). Enemies of freedom: Understanding right-wing authoritarianism. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [ Links ]

Ashmore, J. A., Friedman, K. E., Reichmann, S. K., & Musante, G. J. (2008). Weight-based stigmatization, psychological distress, and binge eating behavior among obese treatment-seeking adults. Eating Behaviour, 9(2), 203-209. [ Links ]

Baron, R., & Kenny, D. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173-1182. [ Links ]

Blaine, B., & Williams, Z. (2004). Belief in the controllability of weight and attributions to prejudice among heavyweight women. Sex Roles, 51(1-2), 79-84. [ Links ]

Blass, T. (1995). Right-wing authoritarianism and role as predictors of attributions about obedience to authority. Personality and Individual Differences, 19(1), 99-100. [ Links ]

Caballero, B. (2007). The global epidemic of obesity: An overview. Epidemiological Review, 29(1), 1-5. [ Links ]

Carels, R. A., Young, K. M., Wott, C. B., Jarper, J., Gumble, A., Wagner, M., & Clayton, A. M. (2009). Weight bias and weight loss treatment outcomes in treatment-seeking adults. Annual Behavioral Medicine, 37(3), 350-355. [ Links ]

Carr, D., & Friedman, M. A. (2005). Is obesity stigmatizing? Body weight, perceived discrimination, and psychological well-being in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(3), 244-259. [ Links ]

Crandall, C. S. (1994). Prejudice against fat people: Ideology and self-interest. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(5), 882-894. [ Links ]

Crandall, C., & Biernat, M. (1990). The ideology of anti-fat attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 20(3), 227-243. [ Links ]

Crandall, C. S., & Martinez, R. (1996). Culture, ideology, and antifat attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(11), 1165-1176. [ Links ]

Daníelsdóttir, S., O'Brien, K., & Ciao, A. (2010). Anti-fat prejudice reduction: A review of published studies. Obesity Facts, 3(1), 47-58. [ Links ]

DeJong, W. (1980). The stigma of obesity: The consequences of naive assumptions concerning the causes of physical deviance. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21(1), 75-87. [ Links ]

DeJong, W. (1993). Obesity as a characterological stigma: The issue of responsibility and judgments of task performance. Psychological Reports, 73(3), 963-970. [ Links ]

Ekehammer, B., Akrami, N., Gylje, M., & Zakrisson, I. (2004). What matters most to prejudice: Big five personality, social dominance orientation or right wing authoritarianism? European Journal of Personality, 18(6), 463-482. [ Links ]

Falkner, N. H., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., Jeffery, R. W., Beuhring, T., & Resnick, M. D. (2001). Social, educational and psychological correlates of weight status in adolescents. Obesity Research, 9(1), 32-42. [ Links ]

Haslam, D. W., & James, W. P. (2005). Obesity. Lancet, 366(9492), 1197-1209. [ Links ]

Hansson, L. M., & Rasmussen, F. (2010). Predictors of 10-year-olds' obesity stereotypes: A population-based study. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 5(1), 25-33. [ Links ]

Hayden-Wade, H. A., Stein, R. I., Ghaderi, A., Saelens, B. E., Zabinski, M., & Wilfley, D. E. (2005). Prevalence, characteristics, and correlates of teasing experiences among overweight children vs. non-overweight peers. Obesity Research, 13(8), 1381-1392. [ Links ]

Hebl, M. R., & Xu, J. (2001). Weighing the care: Physicians' reactions to the size of a patient. International Journal of Obesity, 25(8), 1246-1252. [ Links ]

Holmbeck, G. (2002). Pos-hoc probing of significant moderation and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(1), 87-96. [ Links ]

Holub, S., Tan, C., & Patel, S. (2011). Factors associated with mothers' obesity stigma and young children's weight stereotypes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(3), 118-126. [ Links ]

Jackson, T. D., Grilo, C. M., & Masheb, R.,M. (2000). Teasing history, onset of obesity, current eating disorder psychopathology, body dissatisfaction, and psychological functioning in binge eating disorder. Obesity Research, 8(6), 451-458. [ Links ]

Magallares, A., & Morales, J. F. (2008, July). Spanish adaptation of the Anti-Fat Attitudes Scale. Paper presented at the III European Congress of Methodology, Oviedo, Spain. [ Links ]

Miller, B., & Lundgren, J. (2010). An experimental study of the role of weight bias in candidate evaluation. Obesity, 18(4), 712-718. [ Links ]

O'Brien, K., Hunter, J., & Banks, M. (2007). Implicit anti-fat bias in physical educators: Physical attributes ideology and socialization. International Journal of Obesity, 31(2), 308-314. [ Links ]

O'Brien, K., Puhl, R., Latner, J., Mir, A., & Hunter, J. (2010). Reducing anti-fat prejudice in preservice health students: A randomized trial. Obesity, 19(1), 7-11. [ Links ]

Pratto, P., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. P. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741-763. [ Links ]

Puhl, R., & Heuer, C. (2009). The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity, 17(5), 941-964. [ Links ]

Roehling, M. V., Roehling, P. V., & Pichler, S. (2007). The relationship between body weight and perceived weight-related employment discrimination: The role of sex and race. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71(2), 300-318. [ Links ]

Roets, A., Van Hiel, A., & Cornelis, I. (2006). Does materialism predict racism? Materialism as a distinctive social attitude and a predictor of prejudice. European Journal of Personality, 20(2), 155-168. [ Links ]

Schwartz, M., Vartanian, L., Nosek, B., & Brownell, K. (2006). The influence of one's own body weight on implicit and explicit anti-fat bias. Obesity, 14(3), 440-447. [ Links ]

Seoane, J., & Garzon, A. (1992). Creencias sociales contemporáneas, autoritarismo y humanismo. Psicología Política, 5, 27-52. [ Links ]

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1993). Racism and support of free-market capitalism: A crosscultural analysis. Political Psychology, 14, 383-403. [ Links ]

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [ Links ]

Silván- Ferrero, M. P., & Bustillos, A. (2007). Adaptación de la escala de Orientación a la Dominancia Social al castellano: validación de la dominancia grupal y la oposición a la igualdad como factores subyacentes. Revista de Psicología Social, 22(1), 3-15. [ Links ]

Skitka, L. J., Mullen, E., Griffin, T., Hutchinson, S., & Chamberlin, B. (2002). Dispositions, scripts, or motivated correction? Exploring competing explanations for ideological differences in attributions for social problems. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(2), 470-487. [ Links ]

Sobel, M. (1988). Direct and indirect effects in linear structural equation models. In J. Long (Ed.), Common problem/proper solutions: Avoiding error in quantitative research (pp. 46-64). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

Van Hiel, A., & Mervielde, I. (2005). Authoritarianism and social dominance orientation: Relationships with various forms of racism. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(11), 2323-2344. [ Links ]

Vartanian, L. R., & Shaprow, J. G. (2008). Effects of weight stigma on exercise motivation and behavior: A preliminary investigation among college-aged females. Journal of Health Psychology, 13(1), 131-138. [ Links ]

Wardle, J., Waller, J., & Fox, E. (2002). Age of onset and body dissatisfaction in obesity. Addict Behaviors, 27(4), 561-573. [ Links ]

World Health Organization. (2000). Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic (Technical report series 894). Geneva: Author. [ Links ]