Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.13 no.4 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2014

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-4.prmi

Predicting Role of the Meaning in Life on Depression, Hopelessness, and Suicide Risk among Borderline Personality Disorder Patients*

Rol predictivo del sentido de la vida sobre la depresión, la desesperanza y el riesgo de suicidio en pacientes con trastorno límite de la personalidad

Joaquín García-Alandete**

José H. Marco Salvador***

Sandra Pérez Rodríguez****

Universidad Católica de Valencia San Vicente Mártir, España

***Departamento de Personalidad, Evaluación y Tratamientos. E-mail: joseheliodoro.marco@ucv.es

****Departamento de Personalidad, Evaluación y Tratamientos. E-mail: mariasandra.perez@ucv.es

Recibido: junio 19 de 2013 | Revisado: abril 21 de 2014 | Aceptado: abril 21 de 2014

Para citar este artículo

García-Alandete, J., Marco, J. H., & Pérez, S. (2014). Predicting role of the meaning in life on depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk among Borderline Personality Disorder patients. Universitas Psychologica, 13(4), 1545-1555. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-4.prmi

Abstract

The relation between the meaning in life and depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk in a sample of Spanish Borderline Personality Disorder patients is analyzed. The hypothesis suggested that meaning in life is a significant negative predictor of these variables. Participants were 80 Borderline Personality Disorder patients (75 women, 5 men) ranged 16-60 years old, M = 32.21, SD = 8.85, from a public mental health service. Spanish adaptations of the Purpose-In-Life Test, the Beck Depression Inventory-II, the Beck Hopelessness Scale, and the Plutchick's Suicide Risk Scale were used. Analysis included descriptive, correlations, and simple linear regression. Results showed that meaning in life was negatively related to depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk. It is necessary to introduce the evaluation of the meaning in life in the assessment of patients with Borderline Personality Disorder and to include in the psychotherapeutic intervention elements to enhance their perception and experience of meaning in life.

Keywords :Meaning in life; depression; hopelessness; suicide risk; borderline personality disorder

Resumen

Se analizan las relaciones entre sentido de la vida, depresión, desesperanza y riesgo de suicidio en un grupo de pacientes con Trastorno Límite de Personalidad. La hipótesis al respecto afirma que el sentido de la vida predice negativamente de estas variables. En el estudio participaron 80 pacientes españoles con Trastorno Límite de Personalidad (75 mujeres, 5 hombres) de un servicio público de salud mental, con edades entre los 16 y los 60 años. Se utilizaron versiones españolas del Purpose-In-Life Test, del Inventario de Depresión-II y la Escala de Desesperanza de Beck y de la Escala de Riesgo Suicida de Plutchick. Los análisis incluyeron estadísticos descriptivos, correlaciones y regresión lineal simple. Los resultados mostraron que el sentido de la vida se relacionó negativamente con la depresión, la desesperanza y el riesgo de suicidio. Se concluye que hay necesidad de introducir la valoración del sentido de la vida en la evaluación de pacientes con Trastorno Límite de Personalidad y de incluir en la intervención psicoterapéutica elementos para mejorar su percepción y vivencia de sentido de la vida.

Palabras clave :Sentido de la vida; depresión; desesperanza; riesgo de suicidio; trastorno límite de personalidad

Introduction

The logotherapy emphasizes the role of self-trascen-dence and productive, experiential, and attitudinal values in the development of the sense of existential fullness, and it is opposite to the 'existential vacuum' (Frankl, 2006; Lukas & Hirsch, 2002; Stark, 2003). Meaning in life is related to experience of freedom, responsibility, self-determination, positive view of life, future, oneself, purpose and accomplishment of existential goals, coping, satisfaction with life, and self-realization. People experiencing meaning in life are better prepared to successfully tackle the vital circumstances, have a strong sense of autonomy, self-determination, and purpose in life. Ryff and Keyes (1995) suggested that a critical component of mental health and personal development includes the conviction and the feeling that life is meaningful. On the contrary, existential vacuum is a negative cognitive-emotional-motivational state associated with hopelessness, perception of lack of control over one's life, and absence of vital goals. The existential vacuum causes a negative and pessimistic attitude towards life as a whole, which is contrary to the perception of independence and control over the circumstances and prevents the activation of resources for their satisfactory resolution.

Several studies show that a poor meaning in life is associated to mental health problems, addiction problems, suicide, depression, hopelessness, and suicide (Beck, Brown, Berchick, Stewart, & Steer, 1990; Clarke & Kissane, 2002; Esposito, Spirito, Boergers, & Donaldson, 2003; Gallego-Pérez, García-Alandete, & Pérez-Delgado, 2009; Noffsing-er & Knoll, 2003). On the contrary, a high meaning in life has been positively associated to mental health and psychological well-being (Chan, 2009; Halama & Dedova, 2007; Ho, Cheung, & Cheung, 2010; Kleftaras & Psarra, 2012; Mulders, 2011; Nygren et al., 2005; Psarra & Kleftaras, 2008; Rathi & Rastogi, 2007; Reker & Woo, 2011; Steger & Kashdan, 2007).

Meaning in life has been validated empirically with valid and reliable instruments, such as the Purpose-In-Life Test ([PIL]; Crumbaugh & Maholic, 1969), whose Part A is probably the most used scale for research purposes on meaning in life from logotherapeutic postulates —the other two parts are based on qualitative principles and used for clinical purposes—. The original PIL-Part A is a 20 item, 7-point Likert-type response format related to different aspects of the meaning in life: meaning, purpose or mission in life, satisfaction with one's life, freedom, fear of death, and valuation of life. Several recent studies have analyzed the psychometric properties of this scale, providing evidence of a good internal consistency (e.g., Jonsén et al., 2010; Schulenberg, Schnetzer, & Buchanan, 2011), although its validity has often been questioned since it measures different concepts (e.g., meaning in life, fear to death, or freedom) by way of social desirability bias, and it is also a scale heavily loaded with values. Another aspect of the PIL that has also been tested on a recurring basis is the structure factor. In this regard, although Crumbaugh and Maholic (1969) considered the PIL-Part A an uni-dimensional scale, the García-Alandete, Rosa, and Sellés (2013) 2-factor model obtained the best fit in a comparative study of the main models of the PIL (Rosa, García-Alandete, Sellés, Bernabé, & Soucase, 2012).

Borderline Personality Disorder, Depression, Hopelessness, and Suicide Risk

The Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) has an estimated prevalence of 1.4% (Lenzenwenger, Lane, Loranger, & Kessler, 2007), and patients are characterized by a general pattern of instability in their interpersonal relationships, self-image, affectivity, and impulsivity, which start at the beginning of adulthood. A main characteristic of BPD is the injurious behaviour (Mendieta, 1997) and the association with a high incidence of completed suicide —up to 10%—, a rate over 50 times higher than the suicide rate among the general population (Oldham, 2006; Torgersen, Kringlen, & Cramer, 2001). The lifetime risk of death by suicide among patients with BPD from 3%—10% (Paris & Zweig-Frank, 2001) and they represent the 9%-33% of all suicides (Runeson & Beskow, 1991). These data indicate the need to study possible factors that reduce the risk of suicide in BPD.

Studies on suicide have traditionally focused on determining the risk factors of the suicidal act or the psychological variables that may explain the suicide attempts, and hopelessness is the best and strongest predictor of either consummate or eventual suicides, over others, such as depression or suicidal ideation (Beck, Brown, & Steer, 1989; Beck, Steer, Kovacs, & Garrison, 1985; Brown, Beck, Steer, & Grisham, 2000; Hawton & van Heeringen, 2009). Individuals who score > 9 in the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS; Beck, Weissman, Lester, & Trexler, 1974) show that they are 11 times more likely to commit suicide than those who rate < 8 (Beck et al., 1989), so hopelessness can identify patients at high risk of suicide (Klonsky, Kotov, Bakst, Rabinowitz, & Bromet, 2012; Kuo, Gallo, & Eaton, 2004). Other factors strongly associated with the risk of suicide are a history of previous suicide attempts, a history of self-harm, MDD or depressive symptoms, impulsivity, unemployment, living alone, low social support, or schizophrenia (Beautrais, 2004; Hawton & van Heeringen, 2009; King et al., 2001; Links et al., 2007; Soderberg, 2001; Soloff, Fabio, Kelly, Malone, & Mann, 2005; Soloff & Chiapetta, 2012; Soloff & Fabio, 2008). Regarding comorbidity and suicide risk, longitudinal studies carried out on depressed people have demonstrated that the highest prediction factor of the risk of future suicide attempts is the presence of a Cluster B personality disorders, mainly BPD (May, Klonsky, & Klein, 2012). BPD is the first robustly replicated predictor of attempts over and above ideation (Bolton, Pagura, Enns, Grant, & Sareen, 2010; Conrad et al., 2009).

However, the presence of risk factors does not fully explain suicidal behavior (Hawton & van Heeringen, 2009). Recently, the research on suicide has focused on skills or beliefs that, while having suicide risk factors, protect the person to commit suicide (Johnson, Gooding, Wood, & Tarrier, 2010; Kazdin, 2003), and meaning in life may be a protective factor.

The aim of this work is to analyse the relation between the meaning in life and depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk in a sample of BPD patients. The hypothesis suggests that meaning in life, as it is assessed with the PIL-10, is a significant negative predictor of depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk.

Method

Participants

The sample was recruited from a public mental health service located in Valencia, Spain. The inclusion criteria included patients between 16-60 years who satisfied the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for BPD (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). The exclusion criteria included psychosis and moderate or severe mental retardation. Participants were European whites and all of them understood Spanish perfectly. The initial sample was made up of 85 participants, but 5 were excluded because they did not meet all the BPD criteria. One participant committed suicide during the analysis phase of this research. Participation was voluntary, participants gave informed consent and no compensation was given to them.

The final sample comprised 80 participants: 75 women (93%), and 5 men (6.3%). The 97.5%, n = 78, of them suffered from another Axis I disorder: 63.8%, n = 51, matched Eating disorders criteria; 15%, n = 12, Substance Dependence; 13%, n = 11, Major Depressive Disorder; 3.8%, n = 3, Anxiety Disorders; and 1.3%, n = 1, Body Dismorfic Disorder. The participants' age ranged 16-60 years old, M = 32.21, SD = 8.85. The time span in which BPD had been taking place was 2-33 years, M = 13.18, SD = 6.97. Table 1 shows other socio-demographic characteristics of participants.

Measures

Purpose In Life-10 Ítems ([PIL-10]; García-Alandete et al., 2013)

Spanish version of the PIL-Part A from the original Crumbaugh and Maholic's (1969), a 10-item Lickert-type scale with seven response categories (both category 1 and 7 have specific labels, and category 4 indicates neutrality) that offers a measure of the meaning in life. The reliability was high in García-Alandete et al. (2013), α = 0.86, and in Rosa et al. (2012) α = 0.86.

Beck Depression Inventory-II ([BDI-II]; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996)

21-item scale with 4 alternatives of response (0-4) that assesses depressive symptomatology and offers several quantitative ranges of depression: absent or minimal (< 13), between slight and moderate (14-19), moderate (20-28), and serious (> 28). The Spanish version for clinical population offered good psychometric properties (Sanz, García-Vera, Espinosa, Fortun, & Vázquez, 2005).

Beck Hopelessness Scale ([BHS]; Beck et al., 1974)

A 20 dichotomic item (true/false) scale designed for the assessment of the negative expectations about the future and personal well-being, and the personal skills to solve the difficulties and achieve success. Level of hopelessness is predictive to eventual suicide in clinic population. The total score ranges from 0 to 20. There are 4 levels of hopelessness: 0-3 = null-minimum, 4-8 = medium, 9-14 = moderate, 15-20 = high. The reliability of this scale was 0.93 and showed internal and temporary stability (Beck & Steer, 1993). It was validated among Spanish population (Viñas et al., 2004).

Suicide Risk Scale ([SRS]; Plutchik, Van Praag, Conte, & Picard, 1989)

Self-applied questionnaire that assesses general risk factors of suicide. It is aimed at discriminating between patients with attempted suicide from those who do not. It consists of 15 dichotomic items (yes/ no) and scores of 6 and above are indicative of suicide risk. The Spanish version reliability was 0.90 (Rubio et al., 1988).

Procedure

Participants fulfilled voluntary the scales used in this study in a clinical session under the supervision of therapists, who were specialist in BPD. Neither therapists nor participants knew the purpose or the assumptions of the present study. Diagnosis for BPD was established in previous sessions, using the SCID-II (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997) and the diagnosis for mental disorders was confirmed with the SCID-I (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002).

Data were analyzed using SPSS 15.0 for the estimation of the internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) and the descriptive statistics of the scales, as well as to analyze the linear regression between meaning in life as a predictor, and depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk as criteria.

Results

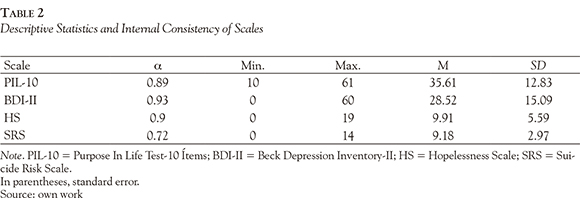

The means of the scales indicated a medium level of meaning in life, serious level of depression, moderate level of hopelessness, and moderate risk of suicide. The internal consistency of the scales was high (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000) (Table 2). The mean in meaning in life was significantly lower, U = 3089.5, p < 0.01, than the obtained by García-Al-andete et al. (2014) among undergraduates, M = 56.91, SD = 7.75.

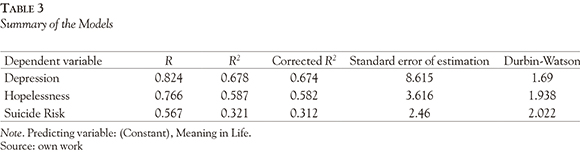

Meaning in life had a negative, significant correlation, p < 0.01, with depression, r = -0.824, hopelessness, r = -0.766, and suicide risk, r = -0.567. A serial of simple linear regression analysis showed that meaning in life predicted 67.8% of the variance of depression, 58.7% of the variance of hopelessness, and 32.1% of the variance of suicide risk (Table 3).

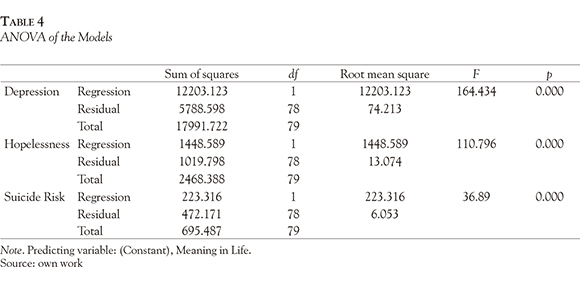

Relationships between meaning in life, as predictor variable, and the measures of depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk, as predicted, were significant (Table 4). The linear dependence in all cases was significant, with what the models were adequate.

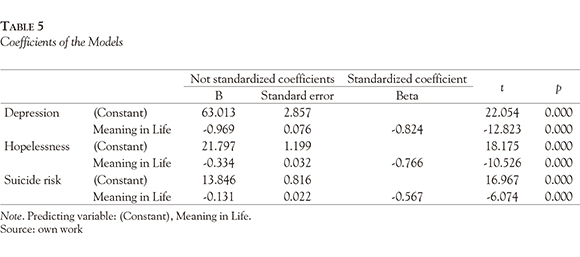

Likewise, non-standardized β coefficients, which indicate the average change corresponding to measures of depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk for unit of change in meaning in life, were significant (Table 5).

Values of non-standardized β coefficients were negative, so the relationship between meaning in life and depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk was inverse: the increase of meaning in life predicted a decrease of depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk. The highest non-standardized β value was associated to depression (closer to 1), followed by hopelessness and suicide risk: depression decreased 0.969 units, hopelessness decreased 0.334 units, and suicide risk decreased 0.131 units, when meaning in life increased by one.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to analyse whether meaning in life is a significant predictive variable of depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk among BPD. The BPD patients' mean in meaning in life was notably lower than that of undergraduates in García-Alandete et al. (2013), and showed a serious level of depression and suicide risk, and moderate level of hopelessness. On the other hand, meaning in life correlated negative, significantly with these clinical variables, and a regression analysis showed that meaning in life is a significant predictor of them, with high percentage of the variance explained for depression, 67.8%, hopelessness, 58.7%, and suicide risk, 32.1%.

Meaning in life, as it is understood from logo-therapy, implies the belief that one's life is useful and oriented towards goals and purposes. It also implies that one is autonomous (not controlled by the circumstances) and has control of one's own life, has a sense of responsibility and existential self-realization (Frankl, 2006). In other words, meaning in life may be a protective factor of welfare and mental health, which would moderate the relationship between stress and depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk; especially in adverse circumstances (Breitbart et al., 2000; Mascaro & Rosen, 2005, 2008; Nelson, Rosenfeld, Breitbart, & Galietta, 2002).

Clinical Implications, Limitations and Future Research

BPD is associated with a high incidence of completed suicide (Oldham, 2006; Torgersen et al., 2001) and a high risk of death by suicide (Paris & Zweig-Frank, 2001). It is necessary to identify the factors that decrease the risk to attempt suicide in order to develop intervention programs aimed at increasing the protection factor in patients with BPD or other psychological disorders. Psychotherapeutic interventions to be developed in patients with BPD will act as protective of suicide risk factors and, to this regard, therapy for BPD (NICE, 2009), the Dialectical Behavioral Therapy ([DBT]; Linehan, 1993), insists that patients identify values deemed necessary to make later changes in their live. In this way, BPD patients can learn to set long-term and short-term goals, like weekly goals and actions based on their vital values to develop meaningful life projects. DBT is effective in the treatment of BPD patients with suicide risk, and it helps to reduce suicide risk (Linehan et al., 2006; Marco, García-Palacios, Navarro, & Botella, 2012). However, we do not know the effect of DBT on meaning in life, and it would be interesting to analyze the effect of current treatments on meaning in life for BPD diagnosed persons.

The relationship between meaning in life, as it is assessed by means of the PIL-10 (García-Alandete et al., 2013), and depression, hopelessness, and suicide risk were confirmed. It would be interesting for future studies in the field of BPD to consider the way that logotherapy explains human behavior, as it seems a promising theoretical approach, mainly with regard to coping the depressive and hopelessnes symptomatology and decrease the suicide risk (Linehan et al., 2006; Marco et al., 2012). Moreover, it is interesting to study the construct of meaning in life in psychopathology and psychotherapy (Rogina, 2004; Schulenberg, Melton, & Foote, 2006), including BPD (Rodrigues, 2004), and its comparison with data in general population.

Our results emphasize the need to introduce the evaluation of meaning in life in the protocols of evaluation of patients with BPD, to assess suicide risk. It is also important to include in the psychotherapeutic intervention elements to enhance meaning in life in these patients. As we noted, logotherapy can provide resources to intervene on depression and hopelessness, minimizing or even eliminating the risk of suicide (Heisel & Flett, 2004). As it is known, it is one of the main therapeutic goals in patients with BPD (Linehan et al., 2006; Marco et al., 2012, Pérez, Marco, & García-Alandete, 2014). Early intervention on meaning in life could act as a protective factor in suicidal behavior, and future studies are necessary to carry out intervention programs that enhance meaning in life in people with some suicide risk factor (Lee, Steen, & Seligman, 2005).

One of the strengths of the present study is that the sample comes from a public mental health institution, and that participants showed several of the main suicide risk factors recognized in the literature: BPD diagnosis, high level of depression, and previous suicide attempts (Black, Blum, Pfohl, & Hale, 2004; Soloff et al., 2000). Likewise, inclusion criteria were very broad, so the sample was representative of patients seen in daily clinical practice, and results obtained in our study may be generalizable to the population of BPD. Furthermore, we can point out that in case of having had a comparable subgroup of men, we could have analyzed the differences associated to gender in the studied variables, as well as their relationships. This is a question to consider in future studies.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed. rev.). Washington, DC: Author. [ Links ]

Beautrais, A. L. (2004). Further suicidal behavior among medically serious suicide attempters. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34(1), 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/suli.34.1.1.27772 [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., Brown, G., Berchick, R. J., Stewart, B. L., & Steer, R. A. (1990). Relationships between hopelessness and ultimate suicide: A replication with psychiatry outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147(2), 190-195. [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1989). Prediction of eventual suicide in psychiatric inpatients by clinical ratings of hopelessness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(2), 309-310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0022-006X.57.2.309 [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1993). Hopelessnes Scale Manual. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace. [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II (2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., Kovacs, M., & Garrison, B. (1985). Hopelessness and eventual suicide: A ten-year prospective study of patients hospitalized with suicidal ideation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 142, 559-563. [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., Weissman, A., Lester, D., & Trexler, L. (1974). The measurement of pessimism: The hopelessness scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(6), 861-865. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0037562 [ Links ]

Black, D. W., Blum, N., Pfohl, B., & Hale, N. (2004). Suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder: Prevalence, risk factors, prediction, and prevention. Journal of Personality Disorders, 18(3), 226-239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.18.3.226.35445 [ Links ]

Bolton, J. M., Pagura, J., Enns, M. W., Grant, B., & Sareen, J. (2010).A population-based longitudinal study of risk factors for suicide attempts in major depressive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 44(13), 817-826. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.01.003 [ Links ]

Breitbart, W., Rosenfeld, B., Pessin, H., Kaim, M., Fu-nesti-Esch, J., Galietta, M., Nelson, C. J., & Brescia R. (2000). Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284(22), 2907-2911. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(2 0000615)88:12<2868::AID-CNCR30>3.0.CO;2-K [ Links ]

Brown, G. K., Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Grisham, J. R. (2000). Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: A 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 371-377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0022-006X.68.3.371 [ Links ]

Chan, D. W. (2009). Orientations to happiness and subjective well-being among Chinese prospetive and in-service teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 29(2), 139-151. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01443410802570907 [ Links ]

Clarke, D. M., & Kissane, D. W. (2002). Demoralization: Its phenomenology and importance. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36(6), 733-742. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01086.x [ Links ]

Conrad, R., Walz, F., Geiser, F., Imbierowicz, K., Lied-tke, R., & Wegener, I. (2009). Temperament and character personality profile in relation to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in major depressed patients. Psychiatry Research, 170(2-3), 212-217. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.09.008 [ Links ]

Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholick, L. T. (1969). Manual of instructions for the Purpose in Life Test. Saratoga, CA: Viktor Frankl Institute of Logotherapy. [ Links ]

Esposito, C., Spirito, A., Boergers, J., & Donaldson, D. (2003). Affective, behavioral, and cognitive functioning in adolescents with multiple suicide atempts. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 33(4), 389-399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/suli.33.4.389.25231 [ Links ]

First, M. B., Gibbon, M., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., & Benjamin, L. S. (1997). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [ Links ]

Frankl, V. E. (2006). The unheard cry for meaning. Psychotherapy and humanism. Boston, MA: Beacon Press. [ Links ]

Gallego-Pérez, J. F., García-Alandete, J., & Pérez-Delgado, E. (2009). Sentido de la vida y desesperanza: un estudio empírico. Universitas Psychologica, 8(2), 447-454. [ Links ]

García-Alandete, J., Rosa, E., & Sellés, P. (in press). Estructura factorial y consistencia interna de una versión española del Purpose-In-Life Test. Universitas Psychologica, 12(2), 517-530. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY12-2.efci [ Links ]

Halama, P., & Dedova, M. (2007). Meaning in life and hope as predictors of positive mental health: Do they explain residual variance not predicted by personality traits? StudiaPsychologica, 49(3), 191-200. [ Links ]

Hawton, K., & van Heeringen, K. (2009). Suicide. The Lancet, 373(9672), 1372-1381. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X [ Links ]

Heisel, M. J., & Flett, G. L. (2004). Purpose in Life, Satisfaction with Life, and Suicide Ideation in a Clinical Sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(2), 127-135. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000013660.22413.e0 [ Links ]

Ho, M. Y., Cheung, F. M., & Cheung, S. F. (2010). The role of meaning in life and optimism in promoting well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(5), 658-663. http://dx.doi.org/10.10Wj.paid.2010.01.008 [ Links ]

Johnson, J., Gooding, P., Wood, A. M., & Tarrier, N. (2010). Resilience as positive coping appraisals: Testing the schematic appraisals model of suicide (SAMS). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(3), 179-186. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.10.007 [ Links ]

Jonsén, E., Fagerström, L, Lundman, B., Nygren, B., Vähäkangas, M., & Strandberg, G. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the Purpose in Life Scale. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 24(1), 41-48. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00682.x [ Links ]

Kazdin, A. E. (2003). Research design in clinical psychology (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Links ]

Kerlinger, F. N., & Lee, H. B. (2000). Foundations of behavioural research (4th ed.). London: Thompson Learning. [ Links ]

King E. A., Baldwin D. S, Sinclair J. M. A., Baker N. G., Campbell M. J., & Thompson C. (2001). The Wes-sex recent in-patient suicide study I: Case-control study of 234 recently discharged psychiatric patient suicides. British Journal of Psychiatry, 178(6), 531-536. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.178.6.531 [ Links ]

Kleftaras, G., & Psarra, E. (2012). Meaning in life, psychological well-being, and depressive symptomatology: A comparative study. Psychology, 3(4), 337-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.34048 [ Links ]

Klonsky, E. D., Kotov, R., Bakst, S., Rabinowitz, J., & Bromet, E. J. (2012). Hopelessness as a predictor of attempted suicide among first admission patients with psychosis: A 10-year cohort study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42(1), 1-10. [ Links ]

Kuo, W. H., Gallo, J. J., & Eaton, W. (2004). Hopelessness, depression, substance disorder, and sui-cidality: A 13-year community based study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(6), 497-501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0775-z

Lee, A., Steen, T. A., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Positive psychology in clinical practice. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 629-651. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144154

Lenzenwenger, M. F., Lane, M. C., Loranger, A. W., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). DSM-IV personality disorders in the national Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry, 62(6), 553-554.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Linehan, M. M., Comtois, K., Murray, A., Brown, M., Gallop, R., Heard, H., & Lindenboim, N. (2006). Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(7), 757-766. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757

Links, P. S., Eynan, R., Heisel, M. J., Barr, A., Korzekwa, M., McMain, S., & Ball, J. S. (2007). Affective instability and suicidal ideation and behavior in patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 21(1), 72-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2007.21.1.72 [ Links ]

Lukas, E., & Hirsch, B. Z. (2002). Logotherapy. In R. F. Massey & S. D. Massey (Eds.), Comprehensive handbook of psychotherapy: Interpersonal/Humanistic/Existential (Vol. 3, pp. 333-356). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

Marco, J. H., García-Palacios, A., Navarro M., & Botella, C. (2012). Aplicación de la Terapia Dialéctica Comportamental a un caso de Anorexia Nerviosa y Trastorno Límite de la Personalidad resistente al tratamiento: seguimiento a los 24 meses. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 21(2), 121-128. [ Links ]

Mascaro, N., & Rosen, D. H. (2005). Existential meaning's role in the enhancement of hope and prevention of depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality, 73(4), 985-1014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00336.x [ Links ]

Mascaro, N., & Rosen, D. H. (2008). Assessment of existential meaning and its longitudinal relations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(6), 576-599. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2008.27.6.576 [ Links ]

May, A. M., Klonsky, E. D., & Klein, D. N. (2012). Predicting future suicide attemps among depressed suicide ideators: A 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(7), 946-952. [ Links ]

Mendieta, D. C. (1997). La conducta autolesiva en el Trastorno Límite de la Personalidad. Información Clínica, 8, 28-29. [ Links ]

Mulders, L. T. E. (2011). Meaning in life and its relationship to psychological well-being in adolescents. Non-published manuscript. Retrieved from http://igitur-archive.library.uu.nl/student-theses/2011-0322-200527/0484504Mulder.pdf [ Links ]

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. (2009). Borderline Personality Disorder: Treatment and management. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health Commissioned by National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. London: Author. Retrieved from http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance [ Links ]

Nelson, C., Rosenfeld, B., Breitbart, W., & Galietta, M. (2002). Spirituality, depression and religion in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics, 43(3), 213-220. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.43.3.213 [ Links ]

Noffsinger, S. G., & Knoll, J. L. (2003). Assessing the risk of suicide and attempted suicide. Drug Benefit Trends, 15(6), 25-31. [ Links ]

Nygren, B., Alex, L., Jonsén, E., Gustavsson, Y., Norberg A., & Lundman, B. (2005). Resilience, sense of coherence, purpose in life and self-transcendence in relation to perceived physical and mental health among the oldest old. Aging and Mental Health, 9(4), 354-362. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1360500114415 [ Links ]

Oldham, J. M. (2006). Borderline personality disorder and suicidality. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(1), 20-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.20 [ Links ]

Paris, J., & Zweig-Frank, H. (2001). A 27- year follow-up study of patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. Comprensive Psychiatry, 42(6), 482-487.http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/comp.2001.26271 [ Links ]

Pérez, S., Marco, J. H., & García-Alandete, J. (2014). Comparison of clinical and demographic characteristics among Borderline Personality Disorder patients with and without suicidal attempts and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors. Psychiatry Research, 220(3), 935-940. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.09.001 [ Links ]

Plutchik, R., Van Praag, H., Conte, H. R., & Picard, S. (1989). Correlates of suicide and violence risk, I: The suicide risk measure. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 30(4), 296-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0010-440X(89)90053-9 [ Links ]

Psarra, E., & Kleftaras, G. (2008). Purpose-in-life-test: Reliability, factorial structure and relation to mental health in a Greek sample. International Journal of Psychology, 43(3-4), 294-294. [ Links ]

Rathi, N., & Rastogi, R. (2007). Meaning in life and psychological well-being in pre-adolescents and adolescents. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 33(1), 31-38. [ Links ]

Reker, G. T., & Woo, L. C. (2011). Personal meaning orientations and psychosocial adaptation in older adults. SAGE Open, 1(1). Retrieved from http://sgo.sagepub.com/content/1/1/2158244011405217.full.pdf+html [ Links ]

Rodrigues, R. (2004). Borderline personality disturbances and logotherapeutic treatment approach. The International Forum for Logotherapy, 27(1), 21-27. [ Links ]

Rogina, J. M. (2004). Treatment and interventions for narcissistic personality disorder. The International Forum for Logotherapy, 27(1), 28-33. [ Links ]

Rosa, E., García-Alandete, J., Sellés, P., Bernabé, G., & Soucase, B. (2012). Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio de los principales modelos propuestos para el Purpose-In-Life Test en una muestra de universitarios españoles. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 15(1), 67-76. [ Links ]

Rubio, G., Montero, I., Jáuregui, J., Villanueva, R., Casado, M. A., Marín, J. J., & Santo-Domingo, J. (1988). Validación de la Escala de Riesgo Suicida de Plutchik en población española. Archivos de Neurobiología, 61 (2), 143-52. [ Links ]

Runeson, B., & Beskow, J. (1991). Borderline personality disorder in young Swedish suicides. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 179(3), 153-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199103000-00007 [ Links ]

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719-727. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719 [ Links ]

Sanz, J., García-Vera, M. P., Espinosa, R., Fortun, M., & Vázquez, C. (2005). Adaptación española del Inventario para la Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II): Propiedades psicométricas en pacientes con trastornos psicológicos. Clínica y Salud, 16(2), 121-142. [ Links ]

Schulenberg, S. E., Melton, A. M. A., & Foote, H. L. (2006). College students with ADHD: A role for logotherapy in treatment. The International Forum for Logotherapy, 29(1), 37-45. [ Links ]

Schulenberg, S. E., Schnetzer, L. W., & Buchanan, E. M. (2011). The Purpose in Life Test-Short Form: Development and psychometric support. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(5), 861-876.http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9231-9 [ Links ]

Soderberg, S. (2001). Personality disorders in parasuicide. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 55(3), 163-167. [ Links ]

Soloff, P. H., & Chiapetta, L. L. (2012). Subtyping borderline personality disorder by suicidal behavior. Journal of Personality Disorders, 26(3), 468-480. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2012.26.3.468 [ Links ]

Soloff, P. H., & Fabio, A. (2008). Prospective predictors of suicide attempts in Borderline Personality Disorder at one, two, and two-to-five year follow-up. Journal of Personality Disorders, 22(2), 123-134. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2008.22.2.123 [ Links ]

Soloff, P. H., Fabio, A., Kelly, T. M., Malone, K. M., & Mann, J. (2005). High lethality status in patients with Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 19(4), 386-399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2005.19.4.386 [ Links ]

Soloff, P. H., Kevin, M. D., Lynch, G., Kelly, T. M., Malone, K. M., & Mann, J. J. (2000). Characteristics of suicide attempts of patients with major depressive episode and Borderline Personality Disorder: A comparative study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(4), 601-608. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.601 [ Links ]

Stark, P. L. (2003). The theory of meaning. In M. J. Smith & P. R. Liehr (Eds.), Range theory for nursing (pp. 125-144). New York, NY: Springer. [ Links ]

Steger, M. F., & Kashdan, T. B. (2007). Stability and specificity of meaning in life and life satisfaction over one year. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(2), 161-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9011-8 [ Links ]

Torgersen, S., Kringlen, E., & Cramer, V. (2001). The prevalence of personality disorder in a community sample. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58(6), 590-596. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590 [ Links ]

Viñas, F., Villar, E., Caparrós, B., Juan, J., Cornellá, M., & Pérez, I. (2004). Feelings of hopelessness in a Spanish university population: Descriptive analysis and its relationship to adapting university, depressive symptomatology and suicidal ideation. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatrical Epidemiology, 39(4), 326-334. [ Links ]