Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Universitas Psychologica

versión impresa ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.13 no.4 Bogotá oct./dic. 2014

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13'4.ifip

Imagining Future Internship in Professional Psychology: A Study on University Students' Representations

Imaginando el futuro en la práctica de la psicología profesional: un estudio de las representaciones de estudiantes universitarios

Viviana Langher*

Benedetta Brancadorü

Marianna D'angeli

Andrea Caputo

Sapienza University of Rome, Italia

Recibido: julio 30 de 2013 | Revisado: mayo 17 de 2014 | Aceptado: mayo 17 de 2014

Para citar este artículo

Langher, V., Brancadoro, B., D'angeli, M., & Caputo, A. (2014). Imagining fu' ture internship in professional psychology: A study on university students' representations. Universitas Psychologica, 13(4), 1589-1601. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13'4.ifip

Abstract

This paper presents a case study of 213 university students of Clinical Psychology that explores affective symbolizations, which structure their relationship with hosting bodies in internship experience. This is in order to detect students' main representations about their role as interns, professional activities and functions they have to comply with and the perceived integra' tion between university education and real work contexts. A questionnaire was administered for the analysis of students' motivational dynamics and expectations activated by imagining their future internship. Four clusters of students have been identified, through multivariate statistical techniques, multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) and cluster analysis (CA). Re' sults were as follows: a general powerlessness, distrust and disinvestment toward internship (17.7%); affiliation with hosting bodies in order to gain increasing acceptance and power (33.8%); high pragmatism, task-orientation and compliance with what the hosting bodies propose (30.8%) and a demand for recognition without any negotiation (17.7%). No relationship is detected between clusters and some illustrative variables related to sex and indicators of academic success, problems and participation. These clusters are conceived along three latent dimensions, which explain 57.9% of the total variance and refer to: disengagement/involvement toward internship experience; powerlessness/omnipotence about using competences and de' valuation/idealization of the hosting body in relation to university training. Overall, two critical issues emerge: the first refers to a gap between university training and internship, the second one deals with discontinuity between the internship and the labor market. Some reflections and implications for practice are discussed.

Keywords : Internship; professional psychology; university students; representations; reflective practice

Resumen

El estudio explora simbolizaciones afectivas que estructuran las relaciones de los estudiantes en la experiencia de prácticas. Con el fin de detectar las principales representaciones de 213 estudiantes universitarios de Psicología Clínica sobre su papel como pasantes, las actividades profesionales, las funciones que tienen que cumplir y la integración entre la educación universitaria y los contextos reales de trabajo, se aplicó un cuestionario para el análisis de la dinámica y las expectativas generadas por la imaginación de su futuro. A través de técnicas estadísticas multivariantes, análisis de correspondencia múltiple (ACM) y análisis de conglomerados (AC), se identificaron cuatro grupos. Los resultados fueron los siguientes: falta de poder en general, desconfianza y desmotivación hacia prácticas (17.7%); afiliación a organismos de alojamiento con el fin de obtener el aumento de la aceptación y poder (33.8%); alto pragmatismo, orientación a la tarea y el cumplimiento de lo que los cuerpos de alojamiento proponen (30.8%) y demanda de reconocimiento sin ninguna negociación (17.7%). No se detectó ninguna relación entre los clústeres y algunas variables ilustrativas relacionadas con el sexo y los indicadores de éxito académico, los problemas y la participación. Estas agrupaciones se conciben como dimensiones latentes que explican el 57.9% de la varianza total y se refieren a: la desconexión/implicación hacia la experiencia de prácticas; impotencia/omnipotencia sobre el uso de las competencias y la devaluación/idealización del cuerpo de alojamiento en relación con la formación universitaria. Surgen dos cuestiones fundamentales: la brecha entre la formación universitaria y las prácticas, la segunda se ocupa de la discontinuidad entre las prácticas y el mercado laboral. Se discuten algunas reflexiones e implicaciones para la práctica.

Palabras clave :Prácticas; psicología profesional; estudiantes universitarios; representaciones; la práctica reflexiva

Professional psychology internship is traditionally regarded as a period of intensive clinical training that gives trainees the opportunity to improve their skills and enables them to obtain a license to practice psychology (Gayer, Brown, Gridley, & Treloar, 2003; Lamb, Baker, Jennings, & Yarns, 1982; Leffler, Jackson, West, McCarty, & Atkins, 2012; Mangione et al., 2006). During this period, trainees consolidate their professional identity through the integration of past experience and the use of psychological knowledge in clinical work (Lipovsky, 1988). Indeed, for students, internship represents an opportunity to meet real situations where psychological competence is implemented (Carli, 2009) and to increase their professional skills (Kenkel & Peterson, 2009; Mangione et al., 2006) consistently with their previous academic training. The contrast between the idea of internship as a direct practical approach to the profession or, on the other side, seen as an experience characterized by reflection on practice, highlights the difficult relationship between trainees and hosting bodies (Nappi, 2001; Nelson, 1995; Shakow, 1978). This relationship is important both in practical and psychological terms (Carli, 2009; Madson, Hasan, Williams-Nickelson, Kettmann, & Sands Van Sickle, 2007; Williams-Nickelson & Prinstein, 2004, 2007).

It is important to make a premise. The Italian Law requires internship in order to access the entrance examination, which allows the registration at the Psychology Certification Board. Because of its mandatory nature, students may show a scarce reflection about the contextualization of their university learning within real work contexts (Carli & Paniccia, 2003). As one's professional identity is developed, there are aspects of learning that require understanding of one's personal beliefs, attitudes and values, within context of those of professional culture; reflection offers an explicit approach to their integration (Epstein, 1999).

As stated by Moon (1999, p. 57):

A generalization that seems to apply to teaching, nursing and social work is the fact that there is relatively little concern for the effect of reflective practice on the subject of professional's action [...] Since the improvement in learning [etc.] is deemed central the purposes of these professions; this seems to be a surprising omission.

In recent years, hosting bodies seem to adopt a competence-based approach for the assessment of trainees' cross competences (Kaslow, Pate, & Thorn, 2005; Kaslow et al., 2004; Roberts, Borden, & Christiansen, 2005; Rodolfa et al., 2005), since it is important that they develop skills that can be used in different work contexts (Daniel, Roysircar, Abeles, & Boyd, 2004; de las Fuentes, Willmuth, & Yarrow, 2005; Elman, Illfelder-Kaye, & Robiner, 2005), such as reflective thinking.

According to many authors (Kaslow & Rice, 1985; Lamb et al., 1982; Solway, 1985), there are stressors regarding the transition to and completion of professional psychology internship that may affect the individual's sense of professional identity. In this regard, internship seems to evoke adolescence: both are transitional phases, one from childhood to adulthood, the other one from student hood to professional autonomy, and deal with identity process. Students may experience issues related to the development of their professional identity and sense of self as competent professionals (Lipovsky, 1988). Such issues are salient for many interns, although some differences exist in how they are manifested, depending on the individual. One of the hallmarks of the developmental process is a sense of identity confusion that arises from the individual exposure to a combination of experiences that demand simultaneous commitment (Erikson, 1968). In such way, trainees are confronted with several tasks and could feel the pressure to do all these things the right way (Lipowsky, 1988). In conclusion, it is important that students take a conscious decision on the hosting body where they have to carry out their internship (Mangione et al., 2006), based on well-defined criteria such as interests, aspirations, desires, insights or even practical elements, such as proximity to home or flexible work schedule of internship.

Professional Psychology Internship in the Italian Context

In order to clarify the context in which we present this work, a short review of the regulations regarding internship in the Italian context will be presented.

According to Law n. 56 of 18 February 1989, psychologists could practice only after having passed the State Board Examination and being registered by the appropriate certification board. The State Board Examination is controlled by a decree from the President of the Republic. To be admitted to the examination, which allows the registration at the National Psychology Certification Board, graduates in Psychology must be in possession of adequate documentation proving the completion of a practical internship, in accordance with modalities established by a decree of the Ministry of Education.

D.M. n. 239/92 establishes that, after the university training in Psychology, an internship has to be completed for a whole year as professional experience in social, clinical, development or general psychology field. It is carried out under the supervision of a tutor within public and private hosting bodies according to a partnership agreement with the university.

D.M. n. 509/99 establishes both a three-year (Bachelor's degree) and a five-year (Specialist degree) university training. It introduces the idea of an early professionalization of students, already at the end of three-year academic education in Psychology, which enables the access to a specific section of the National Psychology Certification Board and places internship along the university training period.

To date, according to D.M. 270/2004, internship required for the license to practice professional psychology has to be completed after the degree attainment again, respectively 500 hours for the three-year course, or a total of 1000 hours for the five-year degree, according to the EuroPsy (or European Certificate in Psychology) framework for education and training for Psychologists in Europe (Lunt et al., 2001).

Nowadays, there are no specific criteria designed to evaluate the quality of internship or its consistence with previous academic training, neither during this experience nor after its completion. In this perspective, it is useful that students relate their university learning and skills to real work contexts, based on aware selection criteria of hosting bodies and on a realistic negotiation with them in their next internship (Langher, 2009; Rubino & Gleijes, 2008).

Aims of the Study

This paper focuses on students' motivational dynamics and expectations activated by imagining their future internship, because they can affect their next internship experience. In more detail, a case study regarding university students in Clinical Psychology is proposed. It allows the exploration of the affective symbolizations organizing their relationship with hosting bodies. This is in order to detect students' main representations about their role as interns, both professional activities and functions they have to comply with and the perceived integration between university education and real work contexts.

Theoretical Framework

The paradigm adopted in this research is based on the relationship between individual and context. By context, we mean the set of collusive affective symbolizations (Carli & Paniccia, 2003). The construct of affective symbolization stems from the bi-logic theory of the mind by Matte Blanco (1975), who considered the logic functioning and the unconscious one as two modes in close interaction that people use to categorize reality: Perception allows the organization of the context in its cognitive meaning, affective symbolization allows its organization emotionally. From this perspective, collusion is defined as a set of shared affective sym-bolizations and involves a socialization process of emotions among individuals participating in the same context, characterized by specific motivational dynamics.

In more detail, four main relational dimensions can be detected, based on McClelland's motivational theory (1985) and its subsequent developments in psychosocial research (Carli & Paniccia, 1999; Langher, 2009), which could organize students' symbolizations about the internship and their future relationship with hosting bodies.

The competence model refers to the ability to take into account the real context and analyze the symbolic and cultural components affecting relationships within the organization, in order to contribute to the achievement of shared production objectives. In this perspective, the function of the trainee aims at integrating his/her learned skills with the specific goals of the institutional work, the product of the organization and clients' demands, through listening, observing, exploring, reporting and sharing of the emotional experience (Carli et al., 2007).

The duty model refers to the tendency to comply with well-defined rules and carry out prescribed tasks, based on a role that is taken for granted (Carli & Paniccia, 2003). In this sense, the trainee is not able to contextualize and develop his/her previous learning, as he/she adopts a passive position without acquiring new skills. The internship is mainly perceived as a mandatory step of professional training in psychology, and as a period of time to be spent as quickly as possible.

The familism model deals with the need to establish friendly relationships and to be part of a group, within a self-referential dynamics, without promoting any product or useful change in the context (Carli & Paniccia, 2003). According to this vision, the trainee shows a dependent attitude because he/she is oriented to affiliate with other professionals and experience a sense of belonging to the hosting body, without considering both his/ her training needs and the specific institutional aims of the organizational context.

The grandiosity model refers to the tendency to have control over others and to be influential on the environment, characterized by greatness of scope or intent. In other words, the trainee could be oriented to impose his/her needs and requirements, without being able to adapt his/herself to the real organizational context. He/she, thus, tends to experience a sense of omnipotence, as a defense from powerlessness, and to devaluate the hosting body's practice in order to perceive him/herself as competent (Carli, Grasso, & Paniccia, 2007).

Method

A questionnaire based on these four relational models (competence, duty, familism and grandiosity) and adapted in this study for the internship investigation was developed, according to a specific methodology used for the exploration of collusive processes (Carli & Paniccia, 1999). Some examples of items are reported for each model as follows:

- Competence: "My priority is to understand how I will be able to use the psychological models I have learned at University in my future hosting body"; "The aim of my internship will be to understand how psychological profession can be useful in a real context in order to deal with users' demands"; "My internship activities will be useful if I will understand how I can be effective for the body's users".

- Duty: "I expect that my future hosting body will have a well-defined and established internship project"; "The aim of my internship will be to fulfill all activities proposed by the body, well and timely"; "My internship activities will be useful if I will be able to diminish the workload of the body".

- Familism: "I hope that my future hosting body will be very welcoming and will make me feel at home"; "The aim of my internship will be to work in a peaceful context and to have positive relationships with colleagues"; "My internship activities will be useful if they will enhance the relationships, trust and collaboration within the working group".

- Grandiosity: "I aim to understand whether my future hosting body will be adequate to my university knowledge"; "The aim of my internship will be to use my previous university knowledge to redefine the body's work practice"; "My internship activities will be useful to the body if my proposal will be used to improve the body's work practice".

This methodology does not propose questions whose meanings are clear and well defined (e.g. satisfaction ratings, surveys on opinion/reputation, or assessments related to past experience and so on). In contrast, the questionnaire examines a complex set of emotional and relational dimensions regarding a multitude of thematic areas, able to identify the specific cultural and symbolic components of participants in the research. This methodology favors the study of relationship between participants' responses, through the use of multivariate statistical techniques, in order to formulate hypotheses about the meaning of symbolic and relational processes affecting motivational attitudes towards internship.

Materials

The questionnaire is made up of two sections. The first one aims at taking some subjects' defining characteristics and academic career information. In more detail, four characteristics are categorized and used as illustrative variables because of their potential relevance for the present study: gender, final grade of three-year university degree (as indicator of academic success), being in-course or out-of-course students in terms of completing studies within the expected duration (as indicator of academic problems) and lesson attendance rate (as indicator of academic participation, because attendance is not mandatory).

The second part of the questionnaire explores students' relational models according to four main motivational dynamics respectively oriented to competence, duty, familism and grandiosity. It includes a total of 40 items requiring a response on a four-point Likert scale (not at all, not much, somewhat, very much), which refer to 10 different thematic areas: general expectations about the internship experience; criteria for choosing the hosting body; first contact and meeting with body managers; knowledge and use of internship project; relationship with the supervisor; perceived usefulness of internship activities; negotiation of internship activities; general goals of the internship; use of psychological knowledge learned at university for the internship practice; relationship between the university and hosting bodies. Each of these areas is assessed by a set of four items concerning all four motivational dynamics detected.

The Cronbach's alpha values showed a satisfactory internal consistency of the 10 items related to each motivational dimension: Competence (α = 0.818), Duty (α = 0.749); Familism (α = 0.802); Grandiosity (α = 0.788).

Participants

Two hundred and thirteen Italian psychology university students completed the questionnaire. All students attended the Master's (Specialist) degree course in "Clinical Psychology for the person, organizations and community" at the Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, affiliated to the Faculty of Medicine and Psychology of Sapienza University of Rome. Participant recruitment was achieved by in-class presentation of the study. Majority of participants were female (79.8%) and their mean age was 25.48 years (SD = 4.01), consistently with general trends on university students' characteristics in relation to specialist degree in psychology within the Italian context (AlmaLaurea, 2012).

Data Analysis Procedures

The first stage of data analysis is the multiple correspondence analysis (MCA), which is a factor analysis procedure carried out on qualitative variables, on both nominal and ordinal scale, allowing the summary of response variability by identifying latent factors. The large number of factors taken into account is determined by both the percentage of inertia, explained by each of them, and the work of clinical interpretation (Ercolani, Areni, & Mannetti, 1998). This is followed by cluster analysis (CA): Groups of participants are identified with the character of maximum uniformity among participants themselves and maximum heterogeneity with respect to other groups. Thus, each cluster is characterized by all modes of response that occur in most participants in that cluster. Finally, we proceeded with the interpretation of clusters and the analysis of their specific positions within the factorial plane (cultural area), in relation to symbolic dimensions represented by factorial axes and specific illustrative variables taken in the research.

Results

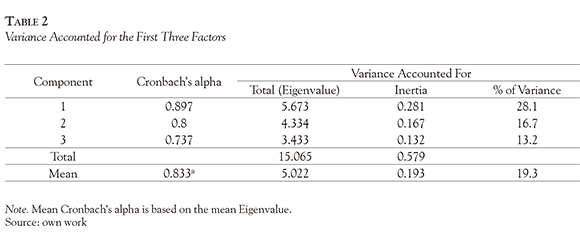

Participants of the present study showed the following characteristics assumed as illustrative variables (Table 1). The first three factors were identified, which explained 57.9% of total variance (Table 2). This allowed the identification of dimensions at the base of data structure, namely a reduced number of ''latent'' dimensions summarizing the interdependence relations of original variables. According to this solution, the CA has revealed an optimum allocation of four groups. This is a technique that, in relation to factors, allows the segmentation of the sample into clusters including study participants who shared more similar characteristics to each other than to those in other clusters.

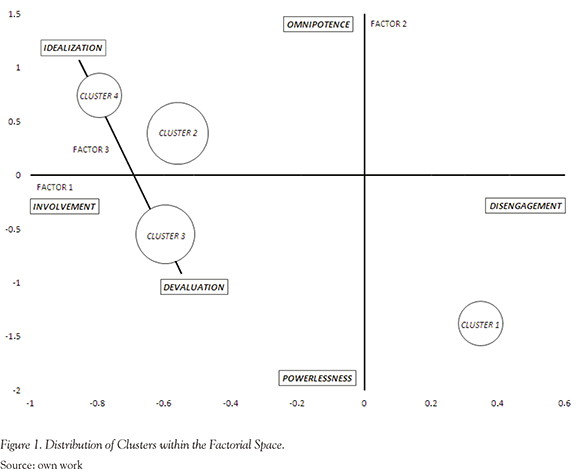

With regard to the association between clusters and illustrative variables, no significant correlation was detected. Below, Figure 1 shows the distribution of clusters within the factorial space, represented graphically on a two-dimensional plane defined by the first two factors and, with respect to which, the third factor is "virtually" perpendicular. Student's t-test (Bonferroni adjustment applied) is used to indicate the specific relationship between clusters and factors, respectively on the positive and negative factorial poles.

Discussion

Clusters

Cluster 1 (17.7% of the sample)

This cluster highlights a general disinvestment and distrust toward the internship experience. It includes students who perceive hosting bodies as mainly unwelcoming, inadequate to their own university training and without a clear and well-defined internship project. Indeed, they complain about the lack of a training function of the internship activities and about the incompetence of the supervisor, depicted as unable to provide effective guidance and support. In this sense, students tend to devaluate the hosting body's practice and imagine a disorienting context characterized by confused roles and rules, where it is not possible to develop a professional competence in psychology. Overall, internship motivation leads to low affiliation with other professionals and poor compliance with what was proposed by hosting bodies. This means that students reject the possibility to get involved in the internship, apply their university learning, achieve training goals and belong to a professional community. thus resulting in a sense of powerlessness with respect to their professional future in psychology.

Cluster 2 (33.8% of the sample)

This cluster includes students who imagine their internship as exclusively oriented to establish a positive relationship with their supervisor and other professionals working in the hosting body, seen as a family context. Indeed, internship activities are mainly perceived as useful to create a peaceful climate promoting confidence and collaboration within teamwork. In this perspective, they experience confusion with regard to knowledge and skills they learned at University. On the one hand, they consider their previous learning as irrelevant since they have to comply with the body's working procedures, thus, avoiding any form of conflict. On the other hand, they think that their university psychological training can improve and change the body's existing practices. This ambivalent dynamic can be explained in terms of their affiliation with other psychologists, seen as a power group only interested in its own professional status: students aim at belonging to the hosting body in order to feel as useful and gain increasing acceptance; but, for this purpose, they are obliged to deny their competences and to assume a passive and dependent role. In this sense, they continue being compliant with prescribed tasks but, at the same time, they secretly keep their myth of the "competent psychologist", as long as they have enough authority or power.

Cluster 3 (30.8% of the sample)

This cluster refers to students who seem to choose the hosting body that provides them a timely, clear and well-defined internship, without expecting cooperation or mutual understanding with other professionals. Indeed, they underline the importance of the first contact and meeting with body managers in order to quickly understand their offering of activities and prescribed tasks, because students do not see any possibility of negotiating or proposing something different. They expect that the supervisor clearly define internship activities, which students have to comply with, rather than provide them support and comfort along their internship. In other words, the internship is mainly perceived as a mandatory step in their professional training and as a period of time to be spent as quickly as possible, according to a duty-oriented tendency. Students seem to imagine a hostile context, which does not contribute to the development of their competences, but takes advantage of trainees to fulfill the hosting body's agenda, and thus, to make a profit for the organization. In this perspective, they accept an unpleasant or difficult situation because there is nothing they can do to improve it, show high pragmatism and task-orientation, without building a specific professional project.

Cluster 4 (17.7%% of the sample)

This cluster includes students who expect to find an adequate hosting body, which is fully consistent with their previous university training. Indeed, they aim at choosing an internship that is both well defined and clear, and that guarantees a welcoming context. In this sense, students highlight their own centrality in the relationship with hosting bodies, since they demand for acceptance based on their taken-for-granted role and claim that their competences are recognized without any negotiation or proven experience. Their high investment in the supervisor, seen as a figure that provides support, clear information and feedbacks, is based on their need for power, for being influential and having control on the organizational context. In other words, these students are likely to be highly demanding, according to both an idealization of the internship experience and an overestimation of their skills. However, this tendency to grandiosity is mainly related to the initial choice of their internship, rather than to practical activities, actual functions and goals to be achieved. In this perspective, their sense of omnipotence could be intended as a defense from powerlessness and fear of something new, rather than an actual feeling of competence.

Factors

The first factor accounts for 28.1% of the total variance and refers to the emotional investment towards internship experience based on a different symbolization of the hosting body's organizational context. On the one hand, disengagement, as the tendency to not be involved in the internship context is seen as disorienting and lowly oriented to professional development; on the other hand, involvement, as a feeling of belonging to a well-defined organization, which contributes to increase students' competences. On the positive pole, cluster 1 highlights the feeling of rejection and distrust about the training usefulness of the internship, the supervisor's guidance, the presence of clear tasks, well-defined practices and roles, which result in a low motivation to approach this experience. On the negative one, clusters 3 and 4 refer to the expectation of being part of the hosting body, respectively regarded as well organized, in terms of higher orientation to efficiency and structured procedures, or as more welcoming, because it values students' centrality and bargaining power about their role.

The second factor accounts for 16.7% of the total variance and refers to students' self-confidence about using their skills. On the one hand, omnipotence, as feeling of grandiosity and attitude to gain centrality and power in the relationship with the hosting body; on the other hand, powerlessness, as perception of lacking competences and being unable to negotiate an internship project. On the positive pole, clusters 2 and 4 suggest students' tendency to increase their influence and strengthen their role, respectively, by affiliating with other professionals within a very collusive dynamic or by overestimating their skills and demanding high professional recognition. On the negative pole, on the contrary, clusters 1 and 3 show a general helplessness linked to students' skepticism regarding the internship's usefulness for their professional development or to students' passive and dependent role complying with prescribed tasks, respectively.

The third factor explains 13.2% of the total variance and refers to the integration between university training and hosting bodies' professional practices. On the one hand, devaluation, as the tendency to deny the usefulness of university training and to highlight the deep distance existing between theory and practice in professional psychology; on the other hand, idealization, as the claiming belief of finding an adequate hosting body, fully consistent with one's own previous knowledge. This factorial axis differentiates cluster 3 on the positive pole and cluster 4 on the negative one. They respectively refer to students' grandiosity fantasies oriented to change and adapt the internship's organizational context to their expectations and, on the other side, to a duty dynamic based on students' compliance with well-established activities, which fulfill the hosting body's agenda rather than promote students' training and development needs.

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to detect certain motivational dynamics, in terms of affective symbolizations, through which students imagine their future internship experience and organize their relationship with hosting bodies. Results show four main clusters, which respectively refer to students who experience a general powerlessness, distrust and disinvestment toward internship (cluster 1); students who affiliate with hosting bodies in order to gain increasing acceptance and power (cluster 2); students who show high pragmatism and task-orientation, complying with what the hosting bodies propose (cluster 3) and, then, students that are highly demanding and expect that their skills be recognized without any negotiation (cluster 4). These clusters are conceived along three latent dimensions.

The first dimension deals with disengagement or involvement, which could affect attitudes toward the internship experience. Disengagement seems to be generally linked to low expectations of professional development, as indicated in a previous study by Cleveland and Williamson (1979) about the reasons for choosing a body. They found that great importance was given to practical training that the institution could provide to facilitate professional growth and increase the chances of finding work. In this regard, Weissman et al. (2006) have emphasized that the relationship between trainees and hosting bodies relates to a mutual feeling of diffidence, which may lead to students' disengagement toward internship: trainees notice a lack of competence in their supervisors and supervisors see trainees as uninterested in learning. In addition, as suggested by literature, the hosting body staff is generally unable to distinguish one trainee from another (Lamb et al., 1982; Rubino & Gleijeses, 2008). Therefore, trainees may not feel appreciated enough, leading to a scarce sense of belonging to the body. On the other hand, there are students who see training as an opportunity to develop confidence in themselves and as a possibility for professional growth; these students live their relationship with the tutor with confidence, which gives trainees the opportunity to work independently and autonomously (Lipowsky, 1988).

The second dimension refers to the impotence-omnipotence continuum about students' using competences. As revealed by Bangen, VanderVeen, Veilleux, and Kamen, (2010), students often receive inadequate university training for the acquisition of skills that can be used during their internship. From this point of view, trainees do not feel able to negotiate the activities that will be proposed by hosting bodies (Olver, Preston, Camilleri, Helmus, & Starzomski, 2011). Therefore, students have difficulties about how to use their skills in hosting bodies, because their training is not effectively oriented to the labor market (Langher, 2009). Students tend to feel impotent and consequently may delegate to the supervisor the tasks they have to comply with or request continuous supervision in order to make their experience meaningful (Dod-son, 1951; Kaslow & Keilin, 2006). Indeed, some students are not in a position to change some of the factors that may place them at a disadvantage (Williams-Nickelson & Prinstein, 2007). On the contrary, students' overconfidence in their abilities can lead to independence from the institution, and to a practice totally unrelated to the supervisor's guidance (Lamb et al., 1982).

The third axis represents the devaluation/idealization of the hosting body in relation to university training. The literature shows how trainees may encounter an organization that offers activities that are based on theories often far from university teaching. This can lead them to devalue the knowledge acquired, regarded as inapplicable in professional contexts, or to refuse bodies, deemed incapable to decline the well-known theoretical models in practice (Weissman et al., 2006). According to this perspective, trainees have the only objective of finishing the experience as soon as possible and are content to carry out activities, even if these have nothing to do with psychology (Olver et al., 2011). According to Madson, Aten, and Leach (2007), students who devalue their training think that they might have some learning opportunities only if they are offered by the tutor.

Implications of the research

As already pointed out above, internship is a crucial time because it allows future professional psychologists to understand how they can work in hosting bodies through using knowledge acquired at university.

From this study two critical issues emerge: the first refers to a gap between university training and internship, the second one deals with discontinuity between internship and the labor market. Therefore, it is important to stimulate the attention of the academic community on work possibilities of future psychologists, looking at students as clients. This is in order to promote an assessment of internship experiences that is not only based on the hosting bodies' fixed minimum requirements, but also includes a continuous reflection on the psychological intervention models and on their consistency with social problems and demands. In this sense, this could promote higher effectiveness of internship. However, the absence of recent studies highlights the difficulties regarding this evaluation process. A possible integration between university knowledge and internship practice comes from negotiating objectives and activities to be involved in, which actually enhance students' professional psychological competence.

As revealed by our study, the lack of such integration could lead to a double-faceted dynamic, focused on powerlessness or omnipotence, as different ways through which trainees face their sense of uncertainty and incompetence. Therefore, the proposal resulting from this study is to focus on exploring affective symbolizations that organize the relationship between the students and the hosting bodies, starting from university training. In detail, dialogue and sharing among students about their expectations and concerns regarding their future role in internship hosting bodies should be promoted in order to increase their empowerment and sense of responsibility as future professionals. To this purpose, it would be desirable that some counseling and guidance initiatives regarding internship be formalized within the university training program.

References

AlmaLaurea. (2012). Profilo dei laureati 2011 [Profiles of graduate students 2011]. Bologna: Università di Bologna. Retrieved from http://www.almalaurea.it/universita/profilo/profilo2011/premessa/pdf_indice [ Links ]

Bangen, K. J., VanderVeen, J. W., Veilleux, J. C., & Kamen, C. (2010). The graduate student viewpoint on internship preparedness: A 2008 Council of University Directors of Clinical Psychology Student Survey. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 4(1), 219-226. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0020111 [ Links ]

Carli, R. (2009). Practical training in the health facilities and mental health centers. Rivista di Psicologia Clinica, 1, 3-16. [ Links ]

Carli, R., Grasso, M., & Paniccia, R. M. (2007). La formazione alla psicologia clinica. Pensare emozioni [Training in clinical psychology. Thinking emotions]. Milano: Franco Angeli. [ Links ]

Carli, R., & Paniccia, R. M. (1999). Psicologia della formazione [Training psychology]. Bologna: Il Mulino. [ Links ]

Carli, R., & Paniccia, R. M. (2003). Analisi della doman-da: Teoria e tecnica dellintervento in psicologia clinica [Analysis of demand: Theory and technique of intervention in clinical psychology]. Bologna: Il Mulino. [ Links ]

Cleveland, S. E., & Williamson, G. A. (1979). Internship recruitment and the VA psychology training program. Professional Psychology, 10(6), 800-807. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.10.6.800 [ Links ]

Daniel, J. H., Roysircar, G., Abeles, N., & Boyd, C. (2004). Individual and cultural diversity competency: Focus on the therapist. Journal of Clinicai Psychology, 80, 755-770. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20014 [ Links ]

de las Fuentes, C., Willmuth, M. E., & Yarrow, C. (2005). Ethics education: The development of competence, past and present. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(4), 362-366. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/07357028.36.4.362 [ Links ]

Dodson, D. W. (1951). Field work and internship in professional training in human relations. Journal of Educational Sociology, 24(6), 337-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2263761 [ Links ]

Elman, N., Illfelder-Kaye, J., & Robiner, W. (2005). Professional development: A foundation for psychologist competence. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(4), 367-375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.4.367 [ Links ]

Epstein, R. (1999). Mindful practice. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 282(9), 833-839. [ Links ]

Ercolani, A. P., Areni, A., & Mannetti, L. (1998). Ricerca in psicologia: Modelli di indagine e di analisi dei dati [Research in psychology: Survey and data analysis models]. Roma: Carocci. [ Links ]

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton. [ Links ]

Gayer, H. L., Brown, M. B., Gridley, B. E., & Treloar, J. H. (2003). Predoctoral psychology intern selection: Does program type make a difference? Social Behavior and Personality, 31 (3), 313-322. http://dx.doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2003.31.3.313 [ Links ]

Kaslow, N. J., Borden, K. A., Collins, F. L., Forrest, L., Illfelder-Kaye, J., Nelson, P. D., ... Willmuth, M. E. (2004). Competencies Conference: Future directions in education and credentialing in professional psychology. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 60(7), 699-712. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20016 [ Links ]

Kaslow, N. J., & Keilin, W. G. (2006). Internship Training in Clinical Psychology: Looking into Our Crystal Ball. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(3), 242-248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.14682850.2006.00031.x [ Links ]

Kaslow, N. J., Pate, W. E., & Thorn, B. E. (2005). Academic and internship directors' perspectives on practicum experiences: Implications for training. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(3), 307-317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.3.307 [ Links ]

Kaslow, N. J., & Rice, D. G. (1985). Developmental stresses of psychology internship training: What training staff can do to help. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 16(2), 253-261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0735-7028.16.2.253 [ Links ]

Kenkel, M. B., & Peterson, R. L. (Eds.). (2009). Competency-based education for professional psychology. Washington, DC: APA. [ Links ]

Lamb, D. H., Baker, J. M., Jennings, M. L., & Yarns, E. (1982). Passages of an internship in professional psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 13(5), 661-669. http://dx.doi.rg/10.1037//0735-7028.13.5.661 [ Links ]

Langher, V. (2009). "The third time is the charm". Considerations regarding training in clinical psychology, awaiting the third reform on the regulation of universities. Rivista di Psicologia Clinica, 2, 60-72. [ Links ]

Leffler, J. M., Jackson, Y., West, A. E., McCarty, C. A., & Atkins, M. S. (2012). Training in evidence-based practice across the professional continuum. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 44(1), 20-28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0029241 [ Links ]

Lipovsky, J. A. (1988). Internship year in clinical psychology training as a professional adolescence. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 19(6), 606-608. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0092783 [ Links ]

Lunt, I., Bartram, D., Döpping, J., Georgas, J., Jern, S., Job, R., ., Herman, E. (2001). EuroPsyT - a framework for education and training for psychologists in Europe. Brussels: European Federation of Psychologists' Associations. Retrieved from http://www.europsyefpa.eu/sites/default/files/uploads/EuroPsy Regulations December 2009.pdf [ Links ]

Madson, M. B., Aten, J. D., & Leach, M. M. (2007). Applying for the predoctoral internship: Training program strategies to help students prepare. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1(2), 116-124. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1931-3918.1.2.116 [ Links ]

Madson, M. B., Hasan, N. T., Williams-Nickelson, C., Kettmann, J. J., & Sands Van Sickle, K. (2007). The internship supply and demand issue: Graduate student's perspective. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1 (4), 249-257. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1931-3918.1.4.249 [ Links ]

Mangione, L., VandeCreek, L., Emmons, L., McIl-vried, J., Carpenter, D. W., & Nadkarni, L. (2006). Unique internship structures that expand training opportunities. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 37(4), 416-422. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.37.4.416 [ Links ]

Matte Blanco, I. (1975). The unconscious as infinite sets: An essay in bi-logic. London: Maresfield Library. [ Links ]

McClelland, D. (1985). Human motivation. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman. [ Links ]

Moon, J. (1999). Reflection in learning and professional development: Theory and practice. London: Kogan Page. [ Links ]

Nappi, A. (2001). Questioni di storia, teoria e pratica del servizio sociale italiano [Issues about story, theory and practice of Italian social services]. Napoli: Liguori. [ Links ]

Nelson, P. D. (1995). Establishing school-based internships in professional psychology. Washington, DC: Office of Educational Research and Improvement. (ERICED 390 021) [ Links ]

Olver, M. E., Preston, D. L., Camilleri, J. A., Helmus, L., & Starzomski, A. (2011). A survey of clinical psychology training in Canadian Federal Corrections: Implications for psychologist recruitment and retention. Canadian Psychology, 52(4), 310-320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024586 [ Links ]

Roberts, M. C., Borden, K. A., & Christiansen, M. (2005). Fostering a culture shift: Assessment of competence in the education and careers of professional psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(4), 355-361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.4.355 [ Links ]

Rodolfa, E. R., Bent, R. J., Eisman, E., Nelson, P. D., Rehm, L., & Ritchie, P. (2005). A cube model for competency development: Implications for psychology educators and regulators. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36(4), 347-354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/07357028.36.4.347 [ Links ]

Rubino, A., & Gleijeses, M. G. (2008). The use of the report in reflection groups on undergraduate practical work. "Between saying and doing there's me...". Rivista di Psicologia Clinica, 2, 190-199. [ Links ]

Shakow, D. (1978). Clinical psychology seen some 50 years later. American Psychologist, 33(2), 148-157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.33.2.148 [ Links ]

Solway, K. (1985). Transition from graduate school to internship: Apotential crisis. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 16(1), 50-54. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.16.1.50 [ Links ]

Weissman, M. M., Verdeli, H., Gameroff, M. J., Bledsoe, S. E., Betts, K., Mufson, L., & Wickramaratne, P. (2006). National survey of psychotherapy training in psychiatry, psychology, and social work. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(8), 925-934. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.925 [ Links ]

Williams-Nickelson, C., & Prinstein, M. J. (Eds.). (2004). Internships in psychology: The APAGS workbook for writing successful applications and finding the right match. Washington, DC: APA. [ Links ]

Williams-Nickelson, C., & Prinstein, M. J. (Eds.). (2007). Internships in psychology: The APAGS workbook for writing successful applications and finding the right match. Washington, DC: APA. [ Links ]