Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Universitas Psychologica

Print version ISSN 1657-9267

Univ. Psychol. vol.14 no.4 Bogotá Oct./Dec. 2015

https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.up14-4.cndu

The Care Network for Drug Users in Brazil: What Do Professionals Say About It?*

La red de atención a los usuarios de drogas en Brasil: ¿qué dicen los profesionales al respecto?

Pedro Henrique Antunes da Costa**

Ana Luísa Marlière Casela***

Daniela Cristina Belchior Mota****

Érika Pizziolo Monteiro*****

Fernando Santana de Paiva******

Jéssica Verônica Tibúrcio de Freitas*******

Nathália Munck Machado********

Telmo Mota Ronzani*********

Federal University of Juiz de Fora, Brasil

*Research Article. Funding: CNPQ, CAPES and FAPEMIG; National Secretariat on Drug Policies (SENAD)

**Researcher at Federal University of Juiz de Fora.phantunes.costa@gmail.com

***Researcher at Federal University of Juiz de Fora.analuisacasela@gmail.com

****Researcher at Federal University of Juiz de Fora. danielabelchior.mota@gmail.com

*****Researcher at Federal University of Juiz de Fora. erik apizziolo@gmail.com

******Professor at Researcher at Federal University of São João del-Rei. fernandosantana.paiva@yahoo.com.br

*******Researcher at Federal University of Juiz de Fora.jessicavtiburcio@gmail.com

********Researcher at Federal University of Juiz de Fora. muncknathalia@gmail.com

*********Professor at Researcher at Federal University of Juiz de Fora. tm.ronzani@gmail.com

Enviado: 1° de marzo de 2015 | Revisado: 1° de junio de 2015 | Aceptado: 1° de agosto de 2015

Para citar este artículo:

Antunes, P. H., Manière, A. L., Belchior, D. C., Pizziolo, É., Santana, F., Tibúrcio, J. V., ... Mota, T. (2015). The care network for drug users: what do professionals say about it? Universitas Psychologica, 14(4), 1311-1324.http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.up14-4.cndu

Abstract

This article aimed to understand, from the framework of community psychology, the care network for drug users from professionals' experiences, and implications of a community level work. Six semi-structured focus groups were conducted with 42 professionals from care networks of four Brazilian cities in the state of Minas Gerais. Data was analyzed through thematic content analysis. Results indicate the need of enhancing network's operational structure and, mainly, consolidating a comprehensive and continuous care model. Professionals' critical views of the care network lift a series of contributions to improve it, with the necessity of embracing a community level work and a resources-focus approach to drug abuse. Related to this, there is the necessity to focus care on community and its needs, by understanding it as the main element of care networks for drug users.

Keywords : delivery of health care; mental health services; public policies; qualitative research; substance-related disorders

Resumen

Este artículo tuvo como objetivo comprender, desde la psicología comunitaria, la red de atención a los usuarios de drogas desde experiencias de profesionales, y las implicaciones de un trabajo a nivel comunitario. Se realizaron seis grupos focales semi-estructurados con 42 profesionales de las redes de atención a los usuarios de drogas de cuatro ciudades brasileñas en Minas Gerais. Los datos fueran analizados mediante análisis de contenido temático. Los resultados indicaron la necesidad de fortalecer la estructura operativa de la red y de consolidar un modelo de atención integral y continua. Opiniones críticas de los profesionales de la red de atención levantan una serie de contribuciones para mejorarla, lo que requiere de un trabajo a nivel de la comunidad y un enfoque centrado en los recursos. Existe la necesidad de centralizar la atención en la comunidad y sus necesidades, entendiendo como el principal elemento de las redes de atención a los usuarios de drogas.

Palabras clave : investigación cualitativa; políticas públicas; prestación de atención de salud; servicios de salud mental; trastornos relacionados con sustancias

Nowadays, drug abuse is a public health issue worldwide (Whiteford et al., 2013). Within the Brazilian and Latin-American context - which shows different iniquities -, such factor is broadened due to the need of addressing not just drug use itself, but its social determinants (Organización Panamericana de la Salud, 2012).

Current policies on such theme in Brazil, since the early 2000s, are based on the construction of intersectoral and integrated care networks to drug users by providing them with a continuous assistance that ranges from health promotion and prevention to treatment and social insertion (Alves, 2009). As indicated by Brazilian Ministry of Health (MS) and National Secretariat on Drug Policies (SEN-AD), contextualized care must address users' needs through a wide range of sectors with specialized and community-based services, varied modalities and treatment approaches (MS, 2004; SENAD, 2005). Only health sector or a single treatment model is not enough to embrace the theme complexity.

Therefore, care networks to drug users encompass organization and teamwork from services, professionals and sectors, such as health sector through Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) and social assistance from Unified Social Assistance System (SUAS). The shared care begins in primary care levels of both sectors, comprised by Family Health Strategy (ESF) services, Family Health Assistance Center (NASF) and street clinics of SUS, together with Social Assistance Reference Centers (CRAS) from SUAS. In specialized level, Psychosocial Care Centers (CAPS) are the main public services for people with mental disorders, with Psychosocial Care Centers for Alcohol and other Drugs (CAPSad) focusing on drug users. The specialized level comprises detoxification in general hospitals, residential care services, among others, and institutions like Specialized Social Assistance Reference Centers (CREAS) of SUAS for severe social vulnerability, exclusion, violence etc. (MS, 2004; SENAD, 2005).

However, recent Brazilian literature shows a series of barriers to consolidating care networks for drug users, such: unawareness of the own network by professionals (Costa, Laport, Mota, & Ronzani, 2013); drug users as passive actors in care process allied with strong moralization of drug use (Paiva, Costa, & Ronzani, 2012); training insufficiency (Cortes, Terra, Pires, Heinrich, Machado, Weiller,... de Mello, 2014); insufficient and disintegrated coverage and a need to rethink care models (Costa, Mota, Paiva, & Ronzani, 2015; Schneider, Roos, Olschowsky, Pinho, Camatta, & Wetzel, 2013).

One way to minimize these problems and to widen care scope is to consider users as part of these networks as well as their social networks and community resources (Paiva et al., 2012). Therefore, besides policies, the present study takes as reference Community Psychology, considering the need to focus on community level. In this case, community is seen as responsible for managing its own life and as an active actor in developing and implementing policies and actions (Gois, 2003; Saforcada, 2012). In this way, there is an attempt of breaking up with assumptions that historically guide health field in Brazil, stating that professionals are the main components of policies and community is a passive element or an action receiver (Saforcada, 2008).

Besides, due to the complexity of the field, traditional public health paradigm becomes limited to effective actions in community, because it focuses on individual aspects - mainly in the pathology - supported by models often restrictive. Community Psychology in this context rises as a way to change the sight, with a resources-focus action that goes towards the people and their relationships with environment, instead of reducing them to their illnesses by institutionalized systems (Lellis, 2011).

Regarding the importance of the theme, a recent review encountered a lack of specific studies on these care networks (Costa et al., 2015). In this insufficient and relatively new scenario, studies are necessary, especially those that aim to have an in depth understanding on the organization of care networks in relation with their contexts. Thus, it is possible to generate evidences that together have some implications on policies without ignoring specificities of different settings and communities.

Formulation and implementation of policies on drugs does not happen in a linear way, since it is surrounded by diverse cultural, social and historical factors (Mota & Ronzani, 2013). Moreover, complexity of the theme raises importance on understand perceptions of actors who are part of this practical context, enabling reflections that contribute to strengthening these networks (Costa et al., 2013). Therefore, knowing professionals' opinions on these care networks could enrich their understanding. Based on this, the current article aims to understand the care network for drug users from professionals' experiences, and the implications of a community level work.

Method

Design

The current study is an exploratory research using qualitative approach. This qualitative approach was chosen because it enables a deeper understanding of care networks for drug users, tracking common aspects, but without disconsidering their particularities. Besides, due to the lack of studies trying to understand these care networks in their natural contexts and the importance of local characteristics, it is interesting that studies focus firstly in describing and comprehending them, instead of coming up with pre-established hypotheses that may be decontextualized.

Participants

Altogether, 42 professionals participated in the study. These participants were from care networks for drug users of a small, two midsize and one large Brazilian cities of the same region in Minas Gerais state. All of them were enrolled in courses at a Regional Reference Center on Drugs (CRR), which is a training center implemented by policies that aims to qualify and reinforce actions of care networks for drug users by permanent training to healthcare, social assistance, security and education professionals.

For participant selection, the following criteria was used: professionals that were being trained by this CRR; people from small, medium and large cities; at least one year of experience in care network; those who would agree to participate in the study. Draws were held in each course, with the selected names being invited to participate.

Data Production

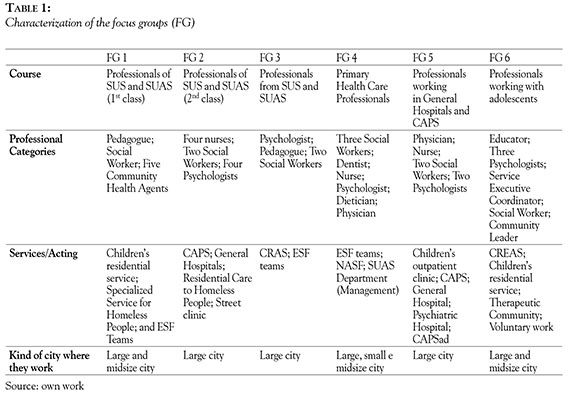

Data was collected through six semi-structured focus groups (FG). FG followed features of courses offered by CRR, as shown in Table 1, and were done in the end of courses. Script addressed professionals' experiences related to drug use and the care network and the challenges and opportunities regarding the role of a community level work in the area. Material was recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis

The data from semi-structured focus groups was analyzed through thematic content analysis (Bardin, 2010). Software Atlas.ti software, version 7.0, was used to support the organization and categorization of the material.

As for the analytical process, all the themes and categories were extracted from the material. In pre-analysis, an initial reading of the material helped researches to familiarize with the contents of documents and to define analysis criteria. It was defined that analysis units would be the sentences, phrases or paragraphs of conversations.

Subsequently, encoding process started, with categories emerging from professionals' speeches. According to the interviewees' statements, text units (or their meaning cores) were extracted and categorized with labels that would resume that statement and provide sense to the narratives (Bardin, 2010). FG were individually categorized, with categories being extracted for each document and then compared with those of other documents by analyzing their pertinence and the need of modifications (grouping categories and renaming, for example).

Finally, all categories - along with the thematic axis - were gathered and results were understood based on their presence and what they meant in relation with study's objectives. Data were interpreted through references of Community Psychology and their interfaces with Community Health. Altogether, six researchers worked independently on analytical process. A judge experienced in content analysis evaluated the categorization consistency and results.

Ethical Aspects

Study was approved by Research Ethics Committee. Participants agreed on research and signed Free and Clear Consent Form. FG were done in place and time approved by professionals. In case of quoting the professionals, sorted letters and a number will represent the interviewee and his/ her FG, but keeping anonymity.

Results

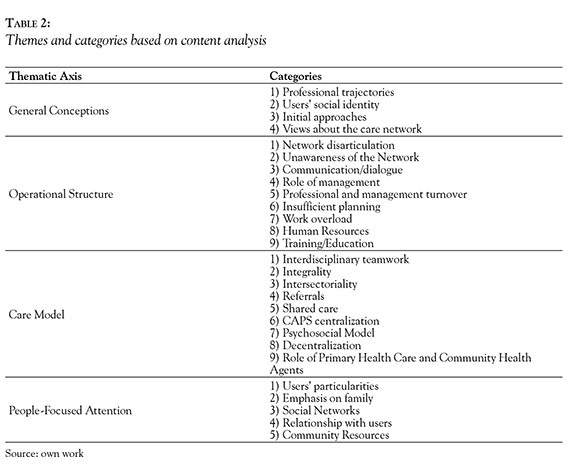

Through the analyses process, the care networks for drug users were understood through four thematic axis. The first one, General Conceptions, encompass categories that represents the understandings about the theme and care network from professionals' experiences. The second one, Operational Structure, describes the structural aspects required to set care network according to professionals' experiences. Subsequently, in Care Model, it is reported the reasoning applied by professionals to provide assistance. Moreover, in the theme People-Focused Attention, it is shown how professionals and their care networks address general population, specially drug users, their views about them and, consequently, how they provide attention and work in this community level. The Table 2 elucidates the categories that appeared in thematic axis.

Although these axis and their categories are presented separately, most of them are related to each other. For example, general experiences on the subject and views about the community influence the care model and should interfere on the operational structure. The same can be seen from some categories.

Professionals' General Conceptions

In general, drug abuse emerges as a relevant theme related to social and health issues, and with professionals struggling to work with it due to factors that will be shown throughout the text. Great heterogeneity was observed among views regarding the theme and care network. This heterogeneity resulted from individual trainings, heterogeneity of roles, professional identities and acting locations.

Related to trajectories, in health sector, performances occur mainly due to two factors. Firstly, there are mental health professionals from CAPS, CAPSad and general hospitals who work with deinstitutionalization process of patients living in psychiatric hospitals and face a big fraction of drug users. Due to these facts, assistance encompasses clinical aspects and emphasizes the potentials of new assistance models, such as the psychosocial approach, instead of traditional hospital-centricity segregating logic. There are also primary health care professionals or those working in general non-specialized services that cover a series of health conditions in which drug use/abuse is responsible for many of those demands. Their narratives show how important it is to discuss the theme but in contrast with an uncertainty on what to do given the nature of services and insufficient training.

Regarding professionals coming from social assistance sector, due to nature of scenarios in which they are inserted and features of their work, focus is given to the relation between individuals, their sociocultural contexts and how drugs emerge as elements among such contexts. Drug use is seen, in some cases as a reflex of the State's neglect, the absence of social policies and guarantee of basic rights.

Other specificities result from the fact that professionals came from different cities, having an impact on network's framework. For example, in small city professionals, there was a management model still trampled on distribution of handouts, with mayor and secretaries as the main actors: "Small towns face their own reality. As I was kidding before, the network is the Secretary and the Mayor. If anything is missing, the user goes straight talking to the mayor" (X, 4).

Social representations of drug users are still based on stigma and moralism. According to professionals, such negative emphasis comes from general population, for whom the user's social identity is crystallized and linked to criminality, marginality and individual aspects such as lack of character and willpower, shamelessness, etc.: "But for those who are outside, I mean, the person is a tramp, doesn't want to do anything, doesn't want to work, is not ashamed of what is doing, and, is maintained by tax payers" (Y, 2).

There were moments when narratives point towards the sharing of viewpoints and behaviors by professionals, directly influencing the methods used to approach users. Besides, there are certain occasions in which social segregation and character deviations give place to irrationalities supposedly caused by drug using or by its disabling chronic character. According to such scenario, initial approaches of the users must focus on his/ her rescue or on developing a 'healthier identity', rather than strengthening his/her condition and life context.

Concept of care network is linked to teamwork, involving services and sectors. Although such assumption was systematically indicated, it emerged without any clear specifications on what the suggested teamwork would actually be. During their sparing attempts to deepen the ideas, professionals end up developing a personalistic attitude, with articulation through personal contacts via referrals or individual initiatives.

Accordingly, by reducing the care network to professionals who comprise it, consequences from the lack of resoluteness also fall over them. Negative aspects appear linked to their motivation and will power -as well as to the managers- to deal with the problem, as it can be seen in the following narrative:

The good and the bad will. One person. Basically, that's what it is summarized to. Willingness to help and grudge hindering. Because, actually, the network is a whole thing comprised by each person, and when one person does not want to disturb, there is another one who does (V, 1).

Operational Structure

The focus of the discussions was related to this theme. Generally, care networks for drug users appear in process of construction and consolidation. There is an entanglement of disconnected services holding themselves on the referrals as the only way to solve the problem. Within this process, networks appear to be insufficient and fragmented or, in some cases, as an idealistic model that is not yet seen in the real context: "A very pretty speech, but a still not consistent practice" (W, 5).

Despite structural deficiency, network disarticulation is the mostly mentioned barrier, been related to lack of dialogue/communication between services. Teamwork and shared care face different barriers to become real, such: unawareness of the network and its services by professionals; need for improving working conditions; high demand and professional workload; professionals and managers turnovers. Therefore, a multiple 'blame fullness' scenario is observed: among users, professionals and managers. Reflections that could be used to highlight challenges and possibilities to minimize barriers are taken by a disbelief sense and immobility that comes from blame fullness.

Related to this, lack of dialogue/communication leads to unawareness about the actions of other services, the referral procedures or teamwork possibilities. "We have no information that is like that, I had no idea of the volume that [the network] had [...] I had no idea of the volume that had. I guess no one had" (X, 4). In this sense, professionals questioned the absence of an institutional care flow, which would work as a way to orientate them on what services and treatment models are more adequate to each case so they could establish a shared care.

Professionals cite management concerning three aspects: 1) lack of State policies on the theme; 2) need of better planning; and 3) need of better working conditions. As for the first aspect, lack of structuring and institutionalizing policies and constant management turnovers make actions embed a personalistic character, with no continuity: "A manager leaves and everybody else is moved, everything changes and then it starts all over" (P, 4). As for planning, professionals point the need of performing situational diagnoses in order to understand features and needs of services and communities, in a way possible to act in a contextualized and effective manner. It goes against the modus operandi of the management, with actions developed and implemented on a top-down basis without professionals' participation.

All of these aspects also lead to a scenario where the working conditions are cited as insufficient. Together with a work overload caused by high demand and insufficient number of human resources, professionals are constrained to carry out what they consider a proper job: " [...] in the meantime we cannot provide attention, because we don't have conditions, minimally, right, [...] we're serving the minimum of the minimum" ' (R, 3).

According to professionals, awareness and continuous training for an extended approach, together with better appreciation of their work conditions are necessary strategies to minimize inadequacies in this field's networks: " [...] on our trajectory itself, within this context, the knowledge that we have in a given time, it is always insufficient, we will always have to get more to give a continuity at work" (Z, 2).

However, despite all difficulties presented for the care network, participants also reported some improvement in this process over time, as can be seen in the following quote: "Today at least we still get a dialogue, which did not exist" (W, 2).

Care Model

Regarding the care model, it was also found a series of difficulties related to the implementation of comprehensive care. Despite the disarticulation between services and levels of care in healthcare and social assistance, the teamwork, according to professionals, is operated in a multi-disciplinary manner instead of an interdisciplinary way. A bunch of professional from different areas that do not necessarily work together.

Individual aspects of users that were directly related to different professional approaches were analyzed in isolation, as wells as they keep assisting only the acute cases (like they were constantly extinguishing fire). Due to such fact, in most of times professionals take isolated actions or apply the referral logic to their own services:

Our contact was like this, well... during welcoming procedures, when they showed up, and we had to set some sort of assistance, we usually referred them to the social assistance staff [...] And from this point on, the contact was between the doctor and the drug user, you know, so the doctor would possibly send him/her to CAPS (Q, 4).

Together with obstacles of implementing integrality, intersectoriality appears as an objective still not achieved. It represents a new manner of work, in which they are not used to in public services: "I think it is very fragile. [...] We try to seek an intersectoral approach with other agencies, but we don't have intersectoriality within the own city hall. this union, right?" (E, 1).

For professionals, the idea of referral is reinforced as a 'safety valve', i.e. main component of shared care, putting users in a passive condition, as objects of comes and goes. It means that in the moment they referral a user to other service, automatically they are sharing that care. In other words, shared care could be reduced to referring patients. According to them, the successful experiences of shared care are resulted of professionals' initiatives, not being institutionalized.

There are moments in health sector when it is possible to observe debates on the difficulties faced by different services such as hospitals, primary health care and the street clinics, specially related to the operational structure presented earlier. However, a wide discussion on CAPS is yet not prioritized. The participants showed an oversized view about specialized services, mainly about CAPS - which is shared with users: "The thing is, well [...] in these assistances, when we observe that there is use of drugs, usually those who arrive to me already come with demand for CAPS, well [...] 'I want to go to CAPS, give me the referral" (A, 3).

In this sense, care based on Psychosocial Model is reduced and centralized in CAPS or CAPSad, with primary scope services like ESF in SUS or CRAS in SUAS left to prevention and referral actions. A great focus is given to outpatient assistance, based on medical consultations, rather than extended psychosocial model. Thus, this centralization can limit other action perspectives or the rising of new initiatives, even in community itself.

Therefore, decentralization appears as a top-down responsibility hierarchy. Such situation reinforces the referral logic and the centralization of actions on specialized services due to high and diversified demand on these generalist services (ESF, CRAS, street clinics etc.), as shown by the following citation:

Our reality, I [think], well, everything was decentralized, and everything fell into the ESF tem. Therefore, the ESF tem, though, must take care of everything. We cannot send them to a psychiatrist, CAPSad, we cannot refer them, so everything must stay in the unit and we make it, we try, try to solve the problem the way it is possible (T, 1).

At primary health care, community health agents (ACS) of ESF teams appear as key-actors in territorialized and community level work, centralizing their attention on community according to their extended local knowledge. However, obstacles found to establish referral and counter-referral, which affects shared care logic be tween specialized services and ESF, also limit ACS' performance and leave them responsible only for giving general information to users and their family members, again in a passive vision of community. Thereafter, professionals report their frustration with management, because of the inefficiencies within the network and with devaluation of their professional category, as well as with other professionals that disregard people's needs and singularities, providing a pasteurized assistance deprived of humanization, which could be reversed by reinforcing ACS' role.

Due to such scenario, the deep ACS contact with population, an aspect that was initially featured as positive, turned into a challenge due to recurrent pressure over them, at the same time they are considered by local actors and community as representatives of policies and, consequently, of their inefficiencies.

Because we are there all day, we experience it all the time. So, I think it would be more feasible, you know, we could have it, you know. That our relationship with them is larger than the rest of the team. So, our will to solve the problems is greater [...] But we also suffer more pressure (D, 1).

People-Focused Attention

With the need to focus the attention on community and population, discussions addressed the requirement of widening the care to address some groups' particularities, such as adolescents, women and homeless people. Most of professionals indicate treatments without considering particularities of these 'different' drug users. The importance of knowing their needs before defining care is consensus among professionals, although practices that promote greater understanding of these needs have not been fully clarified, with actions been based only on 'listening'.

Despite these obstacles, professionals highlight advances, like the new services, such as street clinics and specialized services for people in streets, and some actions taken by CAPS and CAPSad towards the development of works with specific groups based on barm reduction. They agree that a similar treatment outcome (usually abstinence) might not be ideal for all patients. Moreover, although social representation of drug users is still based on stigmatization, with these new services and approaches, professionals also view new possibilities to provide a contextualized and community care in drug users' daily environments, mainly to those with social vulnerability conditions. This view on people-focused attention goes in the opposite way than imposing an ideal life model grounded in personal values as counterpart to treatment.

It was also observed great positive and negative emphasis in family, which appears for them as an element to be worked closely with users, as a source of social support. However, at the same time, an over-liability on families is seen, having consequently the restriction of the users' social networks to his/her family, limiting the focused attention. In addition, drug abuse results from failures in families, with two major implications: 1) this problem is not found within 'structured' families; 2) only family strengthening would necessarily solve most of the problems.

Some professionals compared their approach strategies as a friendship relation in which they have to conquer the users' trust by helping them trust themselves, as shown by the following: "I guess this is important. So, I have to pass him some confidence. 'I trust in you, do you trust in yourself?'

[...] 'You have to trust in yourself, because I trust in you, right?" (K, 6). For this, they highlight the importance of user embracement and humanized treatment.

Finally, for some professionals the necessity of a people-focused attention based on a community level work is seen as a possibility to deal with the barriers of operational structure and the limitations of traditional care model. Instead of reducing the network to themselves or to the services, which is the common process, some professionals suggest the network should be understood from a comprehensive perspective, going beyond services, professionals and encompassing the users, their social networks the community resources:

Because I think all these networking possibilities have to be considered. The person as a network, his/her family, his/her surroundings, school, [...] the group that's with him/her here now, [.] sharing that moment that can collaborate, and network, you know, the equipment they are sometimes the last case (L, 4).

Discussion

Results indicate the need of enhancing the network's operational structure and, mainly, of consolidating a comprehensive and continuous care model focused on aspects such as health promotion and prevention, going beyond traditional model. There is the necessity to focus the care on community and their needs, by understanding them, as wells as the drug users, as main elements of the care networks for drug users.

It is also observed a scenario of many critics and challenges, limiting professionals from seeing the potential of their actions. In many of the points criticized, professionals do not view or elucidate possibilities to reverse this scenario contributing to stagnation. On the other hand, the network is commonly seen in a static and reified manner with superficial goals. In this way, it is questioned whether such generic goals are beforehand unreachable, making professionals emphasize and limit their perception to negative and limiting aspects. Although these generic goals work as slogans to approach the problem, when naturalized, without problematization or contextualization, they may trigger discouragement to professionals who fail achieving them.

However, besides these aspects, the critical view of the care network from participants' experiences lifts a series of contributions to improve it, with the necessity of embracing a community level work and a resources-focus approach to drug abuse. Instead of a polarized debate, a complementation of viewpoints is necessary, in a way to comprehend drug users widely. An example of this comprehensive view is seen in professionals that deal with social vulnerability conditions and losses of rights in a daily basis and are able to also encompass the social aspects of drug abuse by understanding the historical and contextual dimensions involved with it, or, as mentioned by Sarriera (2010), understanding reality from its own complexity.

According to policies, understanding drug abuse as a chronic health condition demands an integral and intersectoral care, approaching it according to a network perspective (MS, 2004; SENAD, 2005). However, agreeing with Schneider (2010), this concept of chronic condition does not mean understanding drug abuse as an irrational and merely biological and/or psychological disease that leads to the 'pathologization' or 'blame fullness' of users. It means that the care must be continuous on the individual and on his/her needs by taking contexts and social determinants under consideration and not simply punctual care focused on the most severe situations.

In accordance with Paiva, Costa and Ronzani (2012), such factors are immersed in scenarios of different social vulnerabilities and structural inequities and, when are not problematized, they can reinforce professionals' 'pedagogic' positions that, along with services and sectors, compose the care network to drug users. Therefore, network (i.e. professionals and managers) becomes the natural responsible for changes in community life because community itself does not have tools or necessary conditions to accomplish such changes.

These aspects indicates the need of thinking beyond the mere expansion of care network. Consonant with Moraes (2008), despite the need of implementing more services, better infrastructure, human resources etc., care models and people-focused attention are not questionable. It is highlighted, though, that one of the factors able to help solving the inadequacies in the network, allowing a more integrated and contextualized assistance, is strengthening community resources by taking them as elements of care network. In this sense, networks' structure are not comprised just by traditional service suppliers, but also by community. However, according to previous studies in Brazil (Costa et al., 2013; Paiva et al., 2012), the concept of the community as a passive agent, surrounded by structural problems that impair community's awareness and strengthening, makes such participatory perspective disregarded.

Regarding this, present data also corroborate results from other researches, showing the occurrence of stigma, which helps to create a social exclusion scenario to users (Silveira & Ronzani, 2011) and the perpetuation of a sheltering assistance logic (Lellis, 2011). It is questioned whether it would be really possible to encompass drug users within their specificities, by centralizing attention on their needs, by standardized and hegemonic treatment models, such as CAPSad, especially when they appear to be replicas of CAPS for general mental disorders. Besides, a study by Federal Court of Accounts (TCU) showed that this service is still insufficient in number throughout the country (TCU, 2012) with difficulties in its implementation and care model, which also may impact on the user not having his/her demand met by any of the services.

The intention here is not to pure criticize or delegitimize CAPS, even less the advances presented in the psychosocial assistance towards the community to people with mental disorders and/ or with problems resulting from drug abuse. The actual point is that there is a need to formulate (or in this case reformulate) care models meeting people's needs and their health conditions.

This also does not mean that one should ignore the necessity of establishing flows, care models, i.e., guidelines. What it is highlighted is that these aspects, although are extreme relevant, must be rationalized according to users, and not on the opposite way. As discussed by Moraes (2008) and Schneider (2010), users are not the ones who must fit the theoretical, clinical and procedure models, but the existing resources must be used according to their features and needs. Most of the results points out to a lack of care flows or an organizational culture that, in accordance with Cortes et al. (2014), should guide care model towards shared logic between services. It is questioned whether there is a possible setting a care network when there are no care guidelines, or whether these guidelines are unknown by actors who are part of the network.

Besides, over the consolidation of a care continuum that encompasses health promotion, prevention and treatment from a contextual ecological perspective, as discussed by Sarriera (2010), the focus should turn on users and community needs, instead of just meeting demands, which are usually severe cases, hard to be solved and beyond health spectrum. As shown by Schneider et al. (2013), centralization in CAPS or CAPSad, letting primary scope services to prevention and referral actions can contribute to stronger hierarchy and fragmentation, rather than strengthening continuous and horizontal shared care. This is seen in the case of ACS, which could play an important role on the implementation of community level work, but are disregarded. In addition, Zambenedetti and Per-rone (2008) point out that primary level services such as ESF in health sector, or recently CRAS in social assistance, are historically more accountable ones, having responsibilities that often are beyond their scope.

Establishing an interdisciplinary teamwork in services does not depend only on the macro structure (i.e. the organizational structure). However, embedded in traditional healthcare paradigm, drug users are fragmented by different views and knowledge of professionals and teams, instead of being approached in their totality. All this reinforces referral logic, as observed by Costa et al. (2013), in which referrals themselves would solve network disarticulation. In addition, referral logic holds on constant responsibility handover to other services/sectors that is also fed back by professionals' sense of incapacity resulting from their insufficient training, deficiencies in system or by complexity of the theme (Costa et al., 2013). Most demands in primary health care levels and social assistance regard cases that need mid or high complexity care and that might be transferred to specialized services such as CAPS and CAPSad. However, two points are questioned: 1) what is the capacity of developing health promotion and prevention actions within high overloaded and structural insufficient contexts?; 2) What is the role of counter-referral, considering its importance in community and territorialized shared care, also preventing raising of new acute situations or crisis?

Due to this reasoning and based on argumentations of Community Health made by Gois (2003) and Saforcada (2008; 2012), the following thoughts are relevant: 1) if one intends to provide care focused on the community and people by taking them as crucial elements in the process, their participation is sine qua non. After all, who knows better about their health than the people themselves or community?; 2) Therefore, what is the best way to deeply understand these people if not with them?

Such action perspective assumes users and their social networks (all individuals and contexts involved in their lives, not only family), as well as community networks and resources, are members of the care network. In this sense, community level work allows the strengthening of these people about their own life conditions, as presented by Montero (2003; 2009), also opening the possibility to bring them to a widened debate about the theme and their lives, consonant with Lellis (2011) and Meneses (2010).

In accordance with Nepomuceno, Ximenes, Moreira and Nepomuceno (2013), such participative approach, based on Community Psychology, in which people (i.e. the users) take the main action and professional appears as a mediator agent, also enables the strengthening of horizontal exchange relations and reliability. Moreover, it indicates that the focus on population does not mean focusing on person only by encompassing just the individual clinical aspects, but also considering contexts in which he/she lives.

This concept of participation also requires community and individuals to be truly involved in daily practices of services. Consonant to Montero (2009) and Sarriera (2011), they cannot be treated as mere targets, but as responsible for planning, conducting and evaluating processes. Due to routines, in many cases professionals find themselves away from these reflections, following automatic and naturalized procedures that disregard peoples' specificities and their dynamics of life. As the main result from such attitudes, users are blamed for not understanding the services and networks goals, for not accessing or taking part in the actions, for not seeking for treatment etc., although the services and their assumptions often ignore the user, not bothering to understand his/her views or, at least, trying to understand their needs.

Therefore, understanding drug users and community as active actors who integrate care network may help understanding them better, as well as working as teams providing contextualized care. As shown by Schneider et al. (2013), in this way, it is possible to involve them on their own life conditions and, hence, motivate them to change. Furthermore, reducing risks linked to drug use by enhancing the quality of life and promoting users' leading role is already a big step and an ethical commitment, as pointed out by Moraes (2008) and Schneider (2010). Finally, agreeing with Paiva et al. (2012) as for the community, a debate triggered by such extended conception may lead to consciousness about complexity of the problem, reducing prejudice and stigma.

Inability to generalize data to other contexts is a limitation of the study, but it is justified by the necessity of a deeper and contextualized analysis. In addition, criteria selection may influence results, with possible differences between participants of the study (that were also trained) from those that did not participate. Another limitation is focusing on professional's views through their experiences. Further studies can aim at understanding users and community views, enabling a broader picture of the scene.

Final considerations

The current study demonstrates that care network for drug users in Brazil is not mere abstraction, but a continuous construction process, instead of static or finished work, involving services, professionals, but also the users and community. This work-and-service-structuring perspective, despite the obstacles, brings together historical advances in a complex and non-consensual area, pervaded by stigma. However, like the crystallization of aspects such as drug use/abuse, users, community etc., the naturalization of these networks may lead to traps that will be unveiled only by critic and continuous reflections. Therefore, not only methods but also theoretical framework, as shown by Community Psychology, should take this dynamicity in consideration.

In this sense, further studies and reflections about the networks in this field should focus on in depth analyses encompassing views of different network actors, but going through, first and foremost, a process of consecutive deconstruction, such: what means to be a drug user, what is known about community and, mainly, deconstructing what is the care network. Is there an ideal model? Is it unique? What are its potentialities and challenges? Why such model should be adopted?

References

Alves, V. S. (2009). Modelos de atenção à saúde de usuários de álcool e outras drogas: discursos políticos, saberes e práticas. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 25(11), 2309-2319. [ Links ]

Bardin, L. (2010) Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70. [ Links ]

Bezerra, E., & Dimenstein, M. (2008). Os CAPS e o trabalho em rede: tecendo o apoio matricial na atenção básica. Psicol ciencprof, 28(3), 632-645. [ Links ]

Cortes, L. F., Terra, M. G., Pires, F. B., Heinrich, J., Machado, K. L., Weiller, T. H., ... de Mello, S. M. (2014). Atenção a usuários de álcool e outras drogas e os limites da composição de redes. Revista Eletrônica de Enfermagem, 16(1), 84-92. [ Links ]

Costa, P. H. A., Laport, T. J., Mota, D. C. B., & Ronzani, T. M. (2013). A rede assistencial sobre drogas segundo seus próprios atores. Saúde em Debate, 37(n. esp.), 110-121. [ Links ]

Costa, P. H. A., Mota, D. C. B., Paiva, F. S. & Ronzani, T. M. (2015, feb.). Unravelling the skein of care networks on drugs: a narrative review of the literature. Cien Saude Colet, 20(2), 395-406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015202.20682013. [ Links ]

Góis, C. W. L. (2003). Psicologia Comunitária. Universitas Ciências da Saúde, 2(1), 277-297. [ Links ]

Lellis, M. (2011). Saúde mental comunitária ou o mental na saúde comunitária? Alternativas de política pública. A crítica do papel do profissional. Em J. C. Sarriera (Org), Saúde Comunitária: Conhe-cimentos e experiências na América Latina. (pp. 167-188). Porto Alegre: Sulina. [ Links ]

Meneses, M. P. R. (2010). Conceitos sobre redes sociais no paradigma ecossistêmico. Em J. C. Sarriera & E. T. Saforcada (Orgs.), Introdução à Psicologia Comunitária: bases teóricas e metodológicas (pp. 97-112). Porto Alegre: Sulina. [ Links ]

Ministério da Saúde (MS). (2004). A Política do Ministério da Saúde para Atenção Integral a Usuários de Álcool e outras Drogas. Brasília: MS. [ Links ]

Montero, M. (2003). Teoría y práctica de la psicología comunitaria: la tensión entre comunidad y sociedad. Buenos Aires: Paidós. [ Links ]

Montero, M. (2009). El fortalecimiento en la comunidad, sus dificultades y alcances. Universitas Psychologica, 8(3), 615-626. [ Links ]

Moraes, M. (2008). O modelo de atenção integral à saúde para tratamento de problemas decorrentes do uso de álcool e outras drogas: percepções de usuários, acompanhantes e profissionais. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 13(1), 121-133. [ Links ]

Mota, D. C. B., & Ronzani, T. M. (2013). Implementação de Políticas Públicas Brasileiras para Usuários de Álcool e Outras Drogas. Em T. M. Ronzani (Org.). Ações integradas sobre drogas: Prevenção, abordagens e políticas públicas (pp. 293-324). Juiz de Fora: Editora UFJF. [ Links ]

Nepomuceno, L. B., Ximenes, V. M., Moreira, A. E. M. M., & Nepomuceno, B. B. (2013). Participação Social em Saúde: Contribuições da Psicologia Comunitária. Psico, 44(1), 45-54. [ Links ]

Organización Panamericana de la Salud. (2012). Salud en las Américas. Panorama regional y perfiles de país. Washington: OPS. [ Links ]

Paiva, F. S., Costa, P. H. A., & Ronzani, T. M. (2012). Fortalecendo redes sociais: desafios e possibilidades na prevenção ao uso de drogas na atenção primária à saúde. Aletheia, 37(1), 57-72. [ Links ]

Saforcada, E. T. (2008). El concepto de salud comunitaria ¿Denomina solo un escenario de trabajo o también una nueva estrategia de acción en salud pública? Psicol. pesq., 2(2), 3-13. [ Links ]

Saforcada, E. T. (2012). Salud comunitaria, gestión de salud positiva y determinantes sociales de la salud y la enfermedad. Aletheia, 37(1), 7-22. [ Links ]

Sarriera, J. C. (2010). O paradigma ecológico na psicologia comunitária. Do contexto à complexidade. Em J. C. Sarriera, & E. T. Saforcada (Orgs.), Introdução à Psicologia Comunitária: bases teóricas e metodológicas (pp. 27-48). Porto Alegre: Sulina. [ Links ]

Sarriera, J. C. (2011). Desafios atuais na saúde comunitária no Brasil. Em J. C. Sarriera (Org), Saúde Comunitária: Conhecimentos e experiências na América Latina. (pp. 246-257). Porto Alegre: Sulina. [ Links ]

Schneider, D. R. (2010). Horizonte de racionalidade acerca da dependência de drogas nos serviços de saúde: implicações para o tratamento. Cien Saude Colet, 15(3), 687-98. [ Links ]

Schneider, J. F., Roos, C. M., Olschowsky, A., Pinho, L. B., Camatta, M. W., & Wetzel, C. (2013). Atendimento a usuários de drogas na perspectiva dos profissionais da estratégia saúde da família. Texto Contexto Enferm, 22(3), 654-661. [ Links ]

Secretaria Nacional de Políticas sobre Drogas (SENAD). (2005). Política Nacional sobre Drogas. Brasília: SENAD. [ Links ]

Silveira, P. S., & Ronzani, T. M. (2011). Estigma social e saúde mental: quais as implicações e importância do profissional de saúde? Revista Brasileira de Saúde da Família, 28, 51-58. [ Links ]

Tribunal de Contas da União (TCU). (2012). Sistema nacional de políticas públicas sobre drogas. Brasília: TCU. [ Links ]

Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H. E., ... Vos, T. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet, 382, 1575-1586. [ Links ]

Zambenedetti, G., & Perrone, C. M. (2008). O Processo de construção de uma rede de atenção em Saúde Mental: desafios e potencialidades no processo de Reforma Psiquiátrica. Physis, 18(2), 277-293. [ Links ]