Introduction

The argument that emotional intelligence (EI) is equally or more important than IQ in professional and business life (Cooper & Sawaf, 1997; Goleman, 1996) has caused the issue to receive deeper analysis and, in the case of this research, has been related to the interest in conducting studies to characterize the EI in Latin American managers.

According to Cartwright and Pappas (2008), the American Society for Training and Development mentions that four out of five companies are trying to identify the EI of employees to increase sales, improve customer service (Cavelzani, Lee, Locatelli, Monti, & Villamira, 2003), and ensure that their managers have performed well internationally. EI is still under study and has been found to have a direct relationship to job performance (Cartwright & Pappas, 2008).

Furthermore, EI has been linked to personal and professional performance of individuals. Anand and UdayaSuritan (2010) mention that EI empowers managers with the ability to sense what others need and want, allowing them to develop strategies to meet those needs and desires.

The characterization of EI has not yet been analyzed in Latin American managers. This article fills that gap by assessing EI in Latin American managers of various economic sectors, by applying the tool developed by Wong and Law (2002) called Emotional Intelligence Scale. Therefore, the aim of the study has a double contribution at the academic level, first through the comparative study to measure and value the EI of Latin American managers based on the application of the Emotional Intelligence Scale of Wong and Law (2002) and, second, through the intent to characterize the EI in Latin American managers.

Theoretical Background

Salovey and Mayer (1990) defined the term EI as “a subset of social intelligence that involves the ability to monitor own and others’ feelings, distinguish and classify them, and use this information to guide our emotions, thoughts, and actions” (p. 189). Furthermore, the authors argued that while social intelligence involves, among other things, the ability to monitor moods and temperaments in others, EI focuses specifically on the recognition and use of our own emotional states in order to solve our problems and regulate our behavior.

Later Mayer and Salovey (1993) decided that EI is not a subset, but rather a type of social intelligence, which also includes the ability to monitor our own emotions, in addition to the ability to monitor the emotions of others. However, the authors noted that the above definitions seem vague because it concerned only to perceive and regulate emotion, omitting thinking about feelings. Therefore, they redefined EI as “the ability to perceive accurately, appraise, and express emotions; the ability to access and / or generate feelings when they facilitate thought; the ability to understand emotions and emotional knowledge; and the ability to regulate emotions to promote emotional and intellectual growth” (Mayer & Salovey, 1997, p. 10).

Based on the definition of EI from Salovey and Mayer (1990), the term was popularized by Goleman (1996) who linked it to the ability to influence the success of people. Thus, the intellectual capacity is relegated to the background and begins to give importance to factors related to the emotional level, such as empathy with others to achieve optimal social relations, knowing one’s own feelings, and not acting impulsively. Goleman (1996) also explains the implications of the concept of EI and presents the adaptation of a broader view of EI suggested by Salovey and Mayer (1990), dividing it into five main competences: a) knowledge of one’s emotions; b) ability to control emotions; c) ability to motivate oneself; d) recognition of others’ emotions; and e) controlling relationships.

To reinforce the definition of the concept of EI, some authors (Cooper & Sawaf, 1997; Goleman, 1996; Mayer & Salovey, 1997; Salovey & Mayer, 1990) claim that the intelligence quotient (IQ), understood both as a degree of ability to perceive and interpret their own emotions, and benefit using the emotions of others, as well as the ability to understand and manage one’s emotions, involves only 20 % of the factors that determine the success (Goleman, 1996). The remaining 80 % corresponds to the factors that are related to what is called EI.

However, despite the efforts made by Mayer and Salovey (1997) to define the term based on the capabilities of EI, there was confusion about the meaning of this theoretical construct. The inclusion of variables that are not capabilities for the construction of the EI may have affected their scientific rigor as a different construct (Schultea, Ree, & Carrettab, 2004). Davies, Stankov, and Roberts (1998) point out that the measures related to EI are the same used in studies of personality. Based on these relationships, and having made several exploratory factor analyzes, the authors concluded that the EI construct was weak. Therefore, Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso (2000, p. 398) defined EI as “the ability to process emotional information accurately and efficiently, including the ability to perceive, assimilate, understand, and regulate emotions”.

This new theoretical approach presents EI as an ability of the person that links emotions and reasoning. It has to use emotions to facilitate more effective reasoning. In particular, Mayer et al. (2000) consider that EI is related to the ability to perceive accurately, with validity and emotional speed, the feelings emanating from the thoughts.

In the last decade, there have been many contributions on EI as a result of its application in empirical studies that analyze the diverse nature underlying specific variables. One focus of the studies is to show the relationship between EI and job performance. In this regard, Jordan, Ashkanasy, Härtel, and Hooper (2002) identify associations of WEIP (Workgroup Emotional Intelligence Profile) with performance measured as goal orientation and process efficiency. Law, Wong, and Song (2004) determined that EI predicts task performance in the workplace. Lastly, Livingstone, Nadjiwon-Foster, and Smithers (2002) relate EI to personal and group development of individuals. Therefore, it is considered of special interest to analyze the characterization of EI in Latin American managers.

EI and Management Role

Research on business management, suggests a relative neglect of the role played by emotions in everyday business life, as this is more attributed to a human relations perspective (Ashforth & Humphrey, 1995). This emotional part can certainly alter the rational aspect of the organization. Argyris (1985) called it “the great paradox of business conduct” (p. 51) where the rational functions to the tasks can be affected by emotional barriers.

In this sense, managers directly affect the emotional climate in a business. Recent research shows that 65 % to 75 % of employees believe that the worst aspect of their job is their immediate boss. This fact is related more to the undesirable qualities of their managers rather than to the lack of desirable qualities or the personality defects of managers (Hogan & Kaiser, 2005). Leslie and Van Velsor (1996) argue that some of the emotions that identify unsuccessful managers are coldness and arrogance, poor interpersonal skills, frequent betrayal of the trust of others, and finding it difficult to work with others. Butler and Chinowsky (2006), in a study conducted in a construction company, identified the weaknesses of EI also corresponded to the components of the area of interpersonal skills, lacking empathy, weak relationships, and poor social responsability.

Schwartz (1990) shows the usefulness of EI in management, since managers who know how to recognize and manage their own emotions, and can determine if the emotion is associated with opportunities or decision problems, use those emotions for decision making. Furthermore, Gardner and Stough (2002) argue that managers with high EI are able to articulate a vision, provide encouragement and sense to employees, stimulate the expression of new ideas, new ways of doing things, and to intervene on problems before they become serious.

Also, Fisher, and Ashkanasy (2000) and Goonan and Stoltz (2004) argue that included in the range of causes that produce certain emotions in the workplace is also the behavior of leaders, including the characteristics of the tasks performed and the level of performance and feedback processes. In addition, possible consequences of these emotions experienced are: job satisfaction, willingness to change, stress, and health.

However, it is common to find that managers have the mistaken assumption that they can manage and lead the organization, and move employees regardless of their emotional aspects (Ashkanasy & Rush, 2004). Employees constantly perceive how their managers express and manage their emotions, and if they respond appropriately to the emotions of their employees; managers being able to understand the emotions of their teams become a key aspect for employees to share their emotions (Smollan & Parry, 2011). This situation is evident when the emotions of managers are contagions to employees and they reproduce the same emotions (Sanchez-Burks & Huy, 2009). This effect has a biological explanation, through mirror neurons (Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004) that reproduce the emotions of managers in their colleagues (Goleman & Boyatzis, 2008). In the words of Fullan (2001), EI, successful social relations, and managing change will be the responsibility of future generations of managers.

Therefore, the instrument used in this research is the Emotional Intelligence Scale developed by Wong and Law (2002). The instrument has been validated by different authors including Aslan and Erkus (2008). They conclude that it may be used in the areas of management, leadership and organizational behavior.

Based on the above arguments, the theoretical foundations and previous studies on EI in managers, there is a general consensus on EI as the ability of individuals to manage emotions and, in turn, includes four factors or variables that better explain the performance of the managers (Acosta-Prado, Zárate, & Pautt, 2015; Goleman, 1996; Law, Wong & Song, 2004; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000; Salovey & Mayer, 1990; Wong, Wong, & Law, 2007).

Variables

Self-awareness. Rating and expression of self-emotions: refers to the ability of each person to understand their deepest emotions and express them naturally. People, who have great skill in this area, feel and raise awareness of self-emotions long before most people.

Empathy. Rating and recognition of emotions in others: refers to the ability of individuals to perceive and understand the emotions of people around them. People who have this ability to a high degree are much more sensitive to the feelings and emotions of others, and also of ‘reading’ their minds.

Self-regulation. Regulating emotions: refers to the ability of people to regulate their emotions, which empowers them to recover more quickly from mood swings and anxiety.

Self-motivation. Using emotions to facilitate performance: refers to the ability of individuals to use their own emotions to route them towards constructive activities and personal performance. A person with great skill in this area remains positive most of the time, using their emotions in the best way to facilitate both high work and personal performance.

Despite the references in the literature, there is no consensus on the size of the EI or the processes needed for efficient development in a leadership role. This study seeks to advance these issues; more specifically, characterizing EI in Latin American managers, through the variables of self-awareness, empathy, self-regulation, and self-motivation.

Methodology

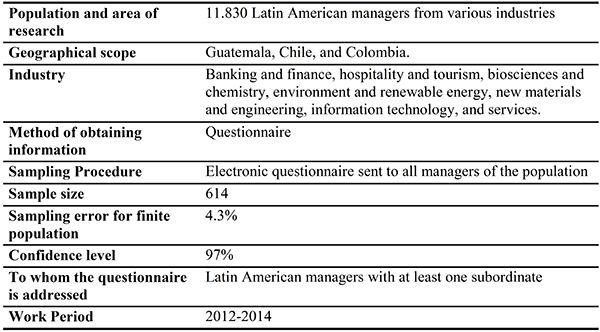

To achieve the research objective, the exploratory study was conducted in a sample of Latin American managers. These managers are suitable for exploratory test for several reasons. Managers must have at least one subordinate in charge, should work in companies in various sectors, and the sample was delimited to Latin American managers from Guatemala, Chile, and Colombia.

The study is exploratory and focuses on Latin American managers who share similar demographic characteristics such as age, education level, and gender. As mentioned, the aim of the study is double, first through a correlational study we intend to characterize in general terms the EI in Latin American managers through the application of the Emotional Intelligence Scale of Wong and Law (2002) and, second, through a cluster study between countries to measure, value and characterize the EI of Latin American managers based on the demographic variables: country, age, gender, and education level.

Management data were obtained from secondary sources such as databases of chambers of commerce, business directories available on the Internet, and publications of Guatemala, Chile, and Colombia during the 2012-2014 period. Managers completed the questionnaire in person. The questionnaire identified the industry, which was categorized as: banking and finance, hospitality and tourism, biosciences and chemistry, environment and renewable energy, new materials and engineering, information technology, and services. Table 1 shows an overview of the questionnaire.

Measurement and analysis

Demographics of managers (identification and control variables) as the variables of EI identified above from the Emotional Intelligence Scale (Wong & Law, 2002) were considered in the questionnaire. To operationalize the type of data scale, a 7-point Likert, participants answered agree or disagree to the affirmation presented in each question from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) grouping variables to measure the factors of EI representing concepts.

Recording and data validation was done with SPSS. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) based on principal components analysis was performed. The objective was to simplify the data, summarizing the information contained in a number of observed variables from Likert type into fewer measures called factors, which did not have a hypothesis about their number nor their structure.

The EFA studies all possibilities to finally select the most likely, according to the data collected (Uriel & Aldás, 2005). It also ensures the unidimensionality, reliability, convergence, and discriminant validity thereof.

As mentioned, there has been an EFA from the technique of principal components and rotation Quartimax iterated. Before it was calculated, the coefficient alpha reliability and contrast of Cronbach for the 16 observed variables measured with a Likert scale of 7 points, used in the questionnaire (Cronbach’s alpha) yielded a value of 0.847. Therefore, the scale is reliable and there is intercorrelation between the variables of the scale (Cronbach, 1951; Thiétart et al., 2003). The measure of sampling adequacy Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin is 0.842, which means that the ratio between the variables is high. Bartlett’s test (χ2 = 3551.319, df = 120 and p = 0.000) rejects the null hypothesis of no significant correlation between the observed variables. In conclusion, it is appropriate to apply the analysis of principal components to the variables.

Subsequently, a cluster analysis was performed, the main purpose of which is to group subjects based on the characteristics they possess, classifying subjects so that each one is very similar to the ones in the cluster with respect to some predetermined selection criteria. The resulting clusters should show a high degree of internal homogeneity and high external heterogeneity (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010).

The theoretical value of the cluster analysis is the set of variables representing characteristics used to compare objects in this analysis, since the theoretical value of the cluster analysis includes only the variables used to compare objects that determine the character of the objects (Johnson, 1998).

Once the variables were selected, the cluster analysis was performed following the approach of using a combination of hierarchical methods: in the first stage of the partition, the method used is from Ward, in order to establish the number of clusters and centroids, corroborating the result with the farthest neighbor method. The Ward method was chosen to minimize internal differences of each cluster and avoid the problems of inadequate initial chaining combinations, which the nearest neighbor method has (Hair et al., 2010).

Results

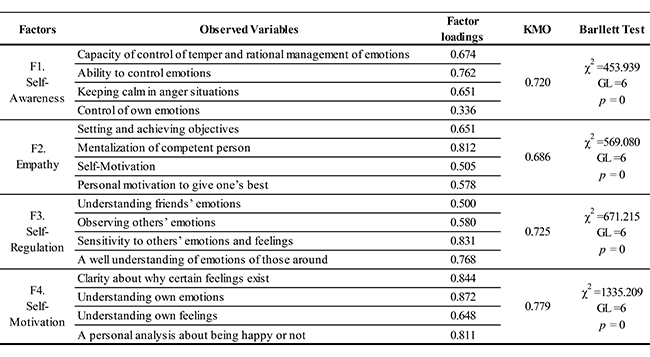

Four consistent factors were identified: Self-Awareness, Empathy, Self-Regulation, and Self-Motivation. The first factor, Self-Awareness, was measured by the following variables: clarity about why certain feelings exist, understanding own emotions, understanding own feelings, and personal analysis about being happy or not. The second factor, Empathy, was measured through the variables: understanding friends’ emotions, observing others’ emotions, sensitivity to others’ emotions and feelings, and a well understanding of emotions of those around. The third factor, Self-Regulation, was measured with the variables: capacity of control of temper and rational management of emotions, ability to control emotions, keeping calm in anger situations, and control of own emotions. The fourth factor, Self-Motivation, was measured through the variables: setting and achieving objectives, mentalization of competent person, self-motivation, and personal motivation to give one’s best.

The EFA has been made with the principal components method. In applying this method, the decision rule allowed for the retention of a significant number of common factors, those with an eigenvalue greater than 1. Moreover, the matrix of coefficients of correlation was used for grouping variables. Together with the principal components method, in order to interpret the retained factors clearly, the method orthogonal rotation process was used through the normalized Quartimax method. The extraction yields a result of four factors retained (with eigenvalue greater than 1). The four factors explain 61.077 % of the total variance of the observed variables.

Then, we proceeded to compare and re-specify, through a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the above four factors. To do this, performing a second sequence in the factor analysis to overcome the limitations of the principal components method was considered appropriate and thus carried out as to be able to contrast and refine new extracted factors. The intent is to strengthen the dimensionality of the factors, the reliability of each as well as the convergent and discriminant validity. Once the CFA and corresponding re-specifications were made, the following four factors were identified, Self-Awareness, Empathy, Self-Regulation, and Self-Motivation. Table 2 shows the CFA results.

The four factors obtained demonstrate significant results. With regard to internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha is calculated with the final variables in each factor. For factor 1 Cronbach’s alpha has a value of 0.86; factor 2 of 0.764; factor 3 of 0.730; and factor 4 of 0.731. According to the literature, the factor 1 shows good internal consistency and the factors 2, 3, and 4 acceptable. Therefore, we conclude that there is convergent validity, reliability, and internal consistency of both the scale and grouped factors.

Note that in the exploratory and confirmatory sequence of factor analysis, it was found that the variables of EI, Self-Awareness, Empathy, Self-Regulation, and Self-Motivation identified in Latin American managers are developed as joint processes that favor the efficient management of managers and more understanding of both the business context and relationships with employees.

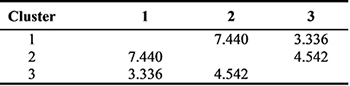

Moreover, the application of cluster analysis allowed grouping and comparing between the three countries (Guatemala, Chile, and Colombia), as table 3 shows. The method chosen was K-means, where it first extracted 3 groups, with the following results.

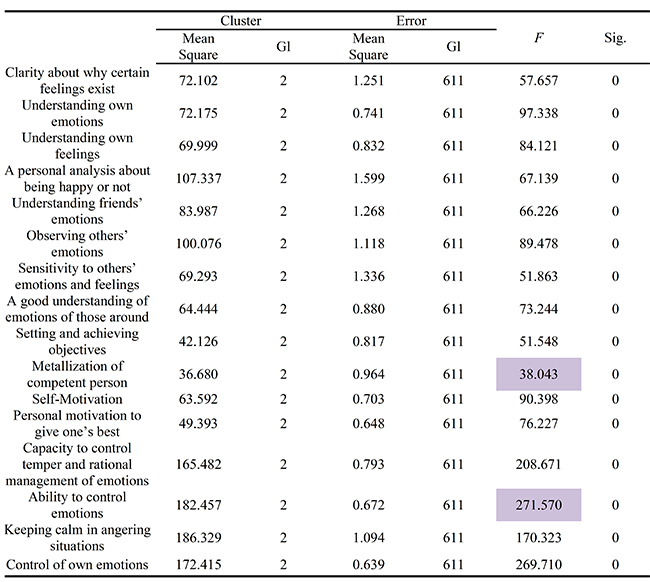

Of the 3 groups, the most distant clusters are 1 and 2 followed by 1 and 3. To confirm the number of groups, an Anova analysis was done, as table 4 shows. This indicates what variables contribute more to the solution of the clusters. Thus, variables with large values of F provide greater separation between the clusters. The variable that provides greater separation between clusters is ’Ability to control emotions’ with F = 271.570. The least separation is, ‘Mentalization of competent person’, with F = 38.043.

The F tests should be used only for descriptive purposes because the clusters have been chosen to maximize the differences among cases in the distinct clusters. Critical levels are not fixed, so it cannot be interpreted as evidence for the hypothesis that the cluster centers are equal.

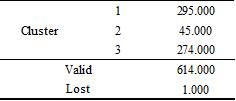

Finally, we proceeded to check the number of cases in each cluster, as table 5 shows. Taking the first group 295 cases, the second group 45 cases, and the third group 274.

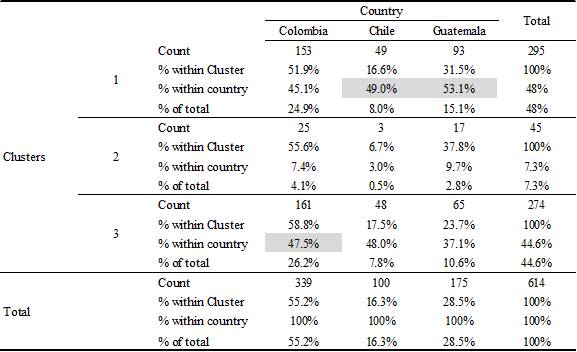

Finally, contingency analyses of the clusters were performed by the demographic variables of the study: country, age, gender, and education level. Table 6 shows that, regarding the variable ’country’, results show that most respondents are from Colombia and belong to cluster 3, while the majority of respondents from Guatemala and Chile belong to cluster 1. Cluster 2 (low capacity of EI), is mostly from Colombia because the highest proportion of respondents are from Colombia. Most other respondents in cluster 2 are from Guatemala.

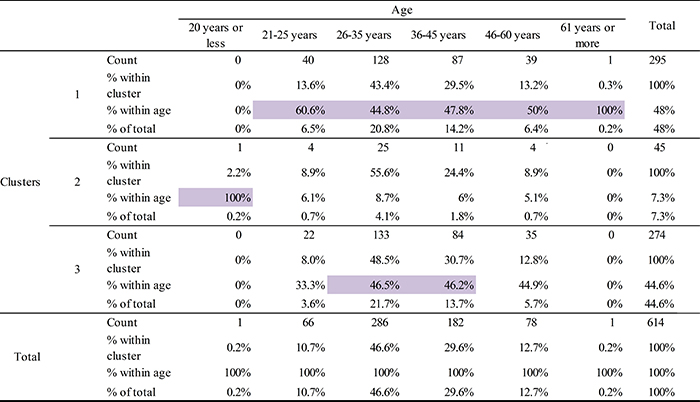

Regarding the variable ’age’, results show that there is no clear pattern between cluster membership and age. Therefore, the proportion of respondents over 21 years old in cluster 2 is low. Also in cluster 2 respondents who are younger than 20 years old were identified. Importantly, this cluster has a low level of emotional intelligence.

Table 7 shows that, the ratio in cluster 1 is high, over 21-61 years-old or more, this conglomerate has a high capacity of EI. Similarly, cluster 3 shows a high proportion, at age 26 to 45 years old.

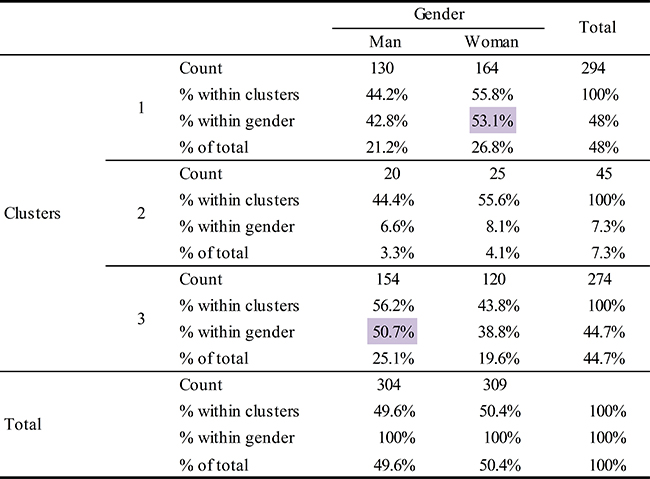

The contingency of the clusters and the variable ’gender’ analysis shows that the majority of respondents who have high emotional intelligence capabilities are women, as table 8 shows. Many men also have high capacity but not as much EI as women.

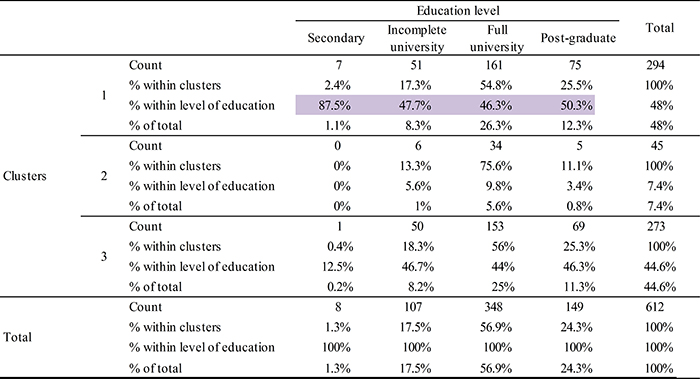

Finally, the contingency analysis of clusters and the variable ’level of education’ in cluster 1 show high values at the secondary level and mean values in levels: incomplete college, college degree, and graduate. In cluster 2, lower values are observed in the levels: incomplete college, university, and postgraduate. Finally, cluster 3 shows mean values in levels: incomplete college, college degree, and graduate. As seen in table 9, cluster 1 has the best values in terms of levels of education and marked therefore high capacity of EI of Latin American managers.

Findings

Among the key findings, we found that the dimensions of EI (self-awareness, empathy, self-regulation, and self-motivation), identified in Latin American managers, were developed as a joint process that favors the efficient management of the managers and a greater understanding of both the business context and interpersonal relationships of collaborators.

The results of the exploratory study support the characterization of EI in Latin American manager. The results highlight the importance of the variables of EI (self-awareness, empathy, self-regulation, and self-motivation) identified because they favor the efficient management of both management and labor, understanding the context and relationships of collaborators. The establishment of a climate of openness and welfare, where they share experiences, ideas, and knowledge, and at the same time, an overall perception of the company is equally important.

Final considerations

The results of the exploratory study show relevant information on the characterization of EI in Latin American managers. As various studies have shown, EI affects professional achievements (Goleman, 1996) and professional achievements usually happen at work, a highly emotional environment (Wong & Law, 2002). These assumptions were crucial both to characterize the profile of Latin American managers and their capabilities in relation to the variables of EI (Self-Awareness, Empathy, Self-Regulation, and Self-Motivation). The research variables allow for the valuing of the abilities of managers to understand and recognize their own emotions and their team members’ by applying the Emotional Intelligence Scale of Wong and Law (2002) composed of 16 7-point Likert variables, assessed in a sample of 614 managers from Guatemala, Chile, and Colombia. Results of the statistical analysis show that there is a positive relationship between the variables of EI (Self-Awareness, Empathy, Self-Regulation, and Self-Motivation) in Latin American managers.

For the analysis of demographic variables, results show that individuals grouped in cluster 1, have a high capacity for EI. This situation is repeated in the same cluster for the variable ‘age’, as more homogeneous values are observed between the ages of 21 to 60 years. In this regard, it should be mentioned that individuals aged 21 to 25 years, exercise levels of management in new ventures or companies in technology sectors, the opposite is true for individuals aged 60 years and older who exercise management levels in companies consolidated mature sectors, mainly services, and banking and finance.

Finally, the variable ‘education level’ reveals that in cluster 1, individuals who possess all levels (high school, unfinished college, complete college, and graduate) have higher values compared to clusters 2 and 3. However, while cluster 1 shows the highest percentages, it exposes the low levels of education of Latin American managers. It is worth mentioning that this variable measures the level of education of managers and not the way they develop their skills and abilities in the performance of the management role.

For the variable ’gender’, although higher values have no distance between them, there are more women in cluster 1 which, as mentioned, indicates these individuals have high capacity and EI; conversely, the higher percentage of men are grouped in cluster 3, that exhibits low capacity EI.

The main implications of the study are theoretical and practical. Theoretically, a conceptual framework is exposed related to EI and Latin American managers, rarely discussed in literature, which has guided and supported the objective of this research. On a practical level, contributions are presented, based on the proposed characterization and its graphical representation, as a proven model that helps company managers, especially those who work in dynamic environments, to understand how the influence of the variables of EI (Self-Awareness, Empathy, Self-Regulation, and Self-Motivation) identified in Latin American managers are developed as a joint process that favors the efficient management of both, understanding context and relationships of team members.