Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Colombia Médica

On-line version ISSN 1657-9534

Colomb. Med. vol.44 no.3 Cali July/Sept. 2013

Original Article

Women's expectations and evaluation of a maternal educational program

Demandas y valoración que hacen las mujeres del programa de educación maternal

Juan Miguel Martínez1, Miguel Delgado2.

1 Andalusian Health Service. University of Jaen. The Biomedical Research Centre Network for Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP).

2 Department of Health Sciences, University of Jaén. CIBERESP

*Corresponding Author.

E-mail Address: juanmimartinezg@hotmail.com(Martínez JM), mdelgado@ujaen.es (Delgado M).

Article history: Received Feb 18 2013 Received in revised form Apr 05 2013 Accepted Jul 24 2013

Abstract

Objectives: To identify the expectations of women requesting the maternal education program (ME) and to determine their evaluation of it.

Methods: a multi-centric observational study was conducted in four hospitals in Spain in 2011 with primiparous women. Socio-demographic and obstetrical variables, among others, were collected through interviews and reviews of medical records. The analysis estimated crude and adjusted odds ratios using logistic regression with a confidence interval of 95%.

Results: Newborn care was most requested type of content desired by women (80.33%). Eleven and one quarter percent (11.25%) of the women evaluated ME as being of little or no usefulness or benefit. Women appreciated the follow-up care given during pregnancy and childbirth but ME was not noted as influencing the measurement of these processes (p >0.05).

Conclusions: Newborn care was the type of subject mainly demanded by the women in the ME program. Women evaluated ME as being a useful program.

Keywords: health education; patient satisfaction; pregnancy; prenatal care.

Resumen

Objetivos: Identificar las demandas que solicita la mujer del programa de educación maternal (EM) y determinar la valoración que hacen de este.

Métodos: Estudio multicéntrico observacional llevado a cabo en cuatro hospitales de España en 2011 con mujeres primíparas. Mediante entrevista y revisión de la historia clínica se recogieron diferentes variables sociodemográficas, obstétricas, entre otras. En el análisis se estimaron odds ratios crudas y ajustadas mediante regresión logística con un intervalo de confianza del 95%.

Resultados: El cuidado del recién nacido fue el tema más solicitado por la mujer (80.33%). El 11.25% de las mujeres valoraron como poco o nada útil y beneficiosa la EM. Las mujeres valoraron positivamente el control de su embarazo y la atención recibida en su parto pero no se detectó influencia de la EM en la valoración de estos procesos (p >0.05).

Conclusiones: El cuidado del recién nacido es el tema que las mujeres demandan mayoritariamente del programa de EM. Las mujeres valoran como útil la realización de la EM.

Palabras Clave: educación sanitaria, satisfacción de la usuaria, embarazo, cuidado prenatal.

Introduction

Maternal Education (ME) is a health education program provided during pregnancy, labor and childbirth that should positively impact the health of mothers and children; therefore, it encompasses a range of educational and support measures that help couples and parents to understand their own social, emotional, psychological and physical needs during pregnancy, labor and parenthood1. In Spain this program is part of the service portfolio of the national health system offering universal and free access, i.e. it is provided at all health centers to all users.

It is mainly carried out in group setting sessions in the third trimester of pregnancy and includes lifestyle norms, theory of pregnancy, physical and psychological preparation for delivery and newborn care, as well as other elements (chat groups and physical exercises). At a minimum, at least three sessions are mandatory and begin in the third trimester2.

Given the current status of ME, several studies have recommended redesign and current ME program evaluations and advise that new strategies and pedagogical approaches should be considered 3-5. Moreover, midwives working in primary care and therefore mainly responsible for providing or developing the ME program are aware that they cannot avoid the social changes taking place in such a complex process as the field of maternal and family health. Hence, they must make adjustments to the content and methodology used to adapt ME programs to the new societal demands, and to program users6. In fact, in the study done by Gallardo and Sánchez7 the majority of midwives (91%) reported that there was a change in expectations by the population in terms of ME and 88% of these health professionals stated that they had made adjustments to the ME program.

No recent studies were found that analyzed the expectations of women in the ME program. There are changes in the perinatal care context made by health administration and this administration also proposes an increasingly central role for citizens that will serve as the basis for the development of new strategies8. An additional consideration is that very few women are attending the current ME program9-11. For all these reasons, the need arose to identify the expectations of women for the ME program, their evaluation of it, as well as to know the effect of ME on user satisfaction with follow-up on the pregnancy and care received at delivery.

Materials and Methods

A multi-centric observational study was conducted between January 2011 and January 2012 at the healthcare centers in the province of Jaén (University Hospital Complex of Jaén and the San Juan de la Cruz de Úbeda Hospital), and at the Poniente in El Ejido (Almería) Hospital and at the University Hospital Virgen de las Nieves of Granada, all of which are located in southern Spain. The reference population was women who gave birth at one of these centers and that met the following inclusion criteria: primiparous, single pregnancy and over 18 years of age.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committees of the respective centers and informed consent was required. A language barrier was established as an exclusion criterion.

The estimation of the sample size was based on the following assumptions. The percentage attending ME was one-third of the total9-11. The general intent of the study was to reduce the number of cesareans, and they fell from 20% to 10% among those receiving ME12,13. A a power of 80% and an alpha error of 5% were established, and 507 women were required for the study. The women were selected consecutively.

Information was collected after childbirth on socio-demographic data (age, sex, marital status, nationality, income, highest educational level achieved, work done during pregnancy, type of contract, sector in which work was done, race and nationality), as well as variables describing the presence of any pathology during pregnancy, pregnancy intent, level of health care provided during pregnancy, adequate prenatal care received (≥ 4 visits for pregnancy follow-up care and the first visit made before the 12th week of pregnancy), abortion history, personal history of disease, prior intent before pregnancy to participate in the ME program, expectations of the women concerning the ME program, user satisfaction with the management of the pregnancy and with the care received during the delivery, and an assessment made by ME participants. For the last three variables a 5-point Likert scale (0-4) was used. The data were collected from an interview of the woman and were validated by the maternal clinical history and medical records. The questionnaire consisted of 140 items (130 closed and 10 open questions) and was applied by 24 previously trained interviewers. In the data analysis, the odds ratio (OR) was estimated for dichotomous variables and the confidence intervals (CI) was set at 95%. Logistic regression was applied in the multivariate analysis retaining as confounding variables those that altered the main exposure coefficient by more than 10%; as potential a priori confounders, the socio-demographic characteristics of the women and the presence of pathology during pregnancy was considered. When the outcome variable was continuous (e.g., degree of user satisfaction with the management of pregnancy) a comparison of means was used, and the multivariate analysis used an analysis of covariance that adjusted for the same variables.

Results

The study involved 520 women, of which 357 (68.65%) had gone to the ME program. The characteristics of the women who participated in the study were as follows: they had a mean age of 29.91 + 5.30 years, 97.88% were white and 64.7% were married; also, 89.62% were Spanish nationals. Of these women, 31.73% had studied at the university level and 46.94% had a monthly income between 1000-1999 Euros. 87.50% of these women were healthy before pregnancy and, in 90% of the cases, the pregnancy was sought. 77.50% of women were having their pregnancy monitored through primary care and 91.80% had good prenatal care.

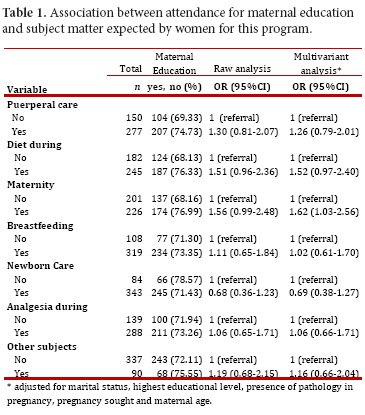

Table 1 documents the association between those having had ME and expectations for issues to be addressed according to participant suggestions. In this regard, of the 427 women that responded, 80.33% of all women wanted the issue of newborn care addressed. 78.57% of women who did not think that newborn care was relevant had received maternal prenatal care, compared to 71.4% who felt it was important (adjusted OR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.38-1.27). Another fundamental content issue that women thought necessary in the ME program was breastfeeding in which 74.71% of the women expressed support.

Of the women who reported breastfeeding as a necessary topic for discussion in ME, 73.35% participated in the ME program, while 71.30% of the women who believed that training on this issue was not needed attended ME sessions (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.65-1.84); after adjustment for marital status, educational level, presence of pathology in pregnancy, sought pregnancy and maternal age, there were no significant differences found (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.61-1.70). 21.08% of the women highlighted as topics to be addressed within the ME program a variety of subjects, including straining, physical exercise, etc. As for the number of issues to be addressed in ME classes there was no significant difference between the group of women who had received ME and those who had not gone through the program (p = 0.092).

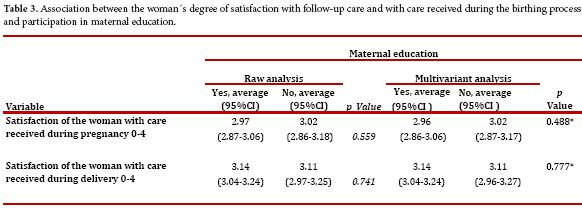

Table 2 shows that 88.75% of the women acknowledged the usefulness and benefit of attending ME sessions, and there is a positive association between the higher the grade given to its usefulness and participant follow through with maternal education (p <0.001) .The degree of satisfaction of women with pregnancy follow-up care and with care received during delivery is quite high, with scores around 3 to a maximum of 4 as can be seen in Table 3. No relationship was observed between participation in the ME program and the degree of satisfaction with care given during pregnancy (p = 0.488), or the degree of satisfaction with the care provided at delivery (p = 0.777) (Table 3). 63.71% of the women who participated in the ME program reported to be very or fairly satisfied compared to 10.53% who indicated being little satisfied or dissatisfied with ME.

Discussion

In general, most women asked for training on newborn care as a subject to be addressed in the ME program. This finding is consistent with other studies1 The topic with the next greatest demand for information concerned breastfeeding, followed by the issue of pain relief during labor, as has been found by other authors14. It was not found that the demand for certain subjects, such as diet, postpartum care, etc. or the number of participants demanding it was influenced by ME attendance.

Health professionals involved with the process of pregnancy, labor and birth can leverage the opportunity provided by ME to sensitize women to the importance of issues such as the postpartum period because, despite the importance of this period and the level of care generally required, it seems that once delivery has occurred and the process finished, lowered levels of alertness and care needs tend to minimize the importance of this period for users15.

Along this line, most postpartum women could benefit from more training acquired through ME for useful postpartum practices and those that may have adverse effects on the health of the mother and the newborn.16 Among the benefits that support postpartum approaches being incorporated into the ME program is the prevention of a health problem of great magnitude with important consequences: postpartum depression17.

A relationship was also not detected between attending ME classes and the degree of satisfaction of women with the follow-up pregnancy care received, or with care received during delivery. Here it worthy to note that women who attended the ME gave a lower evaluation, not statistically significant, to follow-up care received during pregnancy than did those that did not attend. Also, there was no significant relationship found with care received during delivery.

Therefore we cannot conclude that ME influenced the degree of satisfaction with the management of pregnancy and delivery care, contrary to what is mostly found in the scientific literature18-22, although another spanish study5 found results similar to ours.

In most cases, women positively evaluated ME, both considering it useful and beneficial. This evaluation increases with program attendance and is in agreement with other studies1, 23.

The evaluation of the ME program is of vital importance for involving women with health related issues both in the process of pregnancy, labor and childbirth and in other general aspects of health throughout their lifetime24.

If there was a selection bias associated with non-response, it will have had minimal influence on the validity of the results since there is no a priori reason to think that the women who responded substantially differed from non-responders. Nor is it believed very likely that a misclassification bias was introduced because different questions in the questionnaire were completed by the collaborating personnel who previously had been trained not to note different interpretations of the question on the part of the women.

In conclusion, women chiefly expected the subject of newborn care to be a topic to be dealt with at sessions of the ME program. The ME program has been found to be useful for women, whether they make use of it, or not. The ME program does not seem to influence the evaluation of prenatal care processes and birthing, they are independent.

Funding Sources

This research was funded by the Health Research Fund of the Carlos III Institute of Health (PI11/01388)

Acknowledgements

To all the women who voluntarily and disinterestedly participated in the study, and to the staff involved in data collection at the different health centers.

There are no conflicts of interest

References

1. Maroto-Navarro G, García-Calvente MM, Mateo-Rodríguez I. El reto de la maternidad en España: dificultades sociales y sanitarias. Gac Sanit. 2004; 18(Suppl 2):13-23. [ Links ]

2. Junta De Andalucía Consejería de Salud. Proceso Asistencial Integrado Embarazo, Parto y Puerperio. 2nd ed. Sevilla: Consejería de Salud; 2005. [ Links ]

3. Andersson E, Christensson K, Hildingsson I. Parents' experiences and perceptions of group-based antenatal care in four clinics in Sweden. Midwifery. 2012; 28(4): 502-8. [ Links ]

4. Torres Martí JM, Valverde Martínez JA, Melero López A, Priego Correa E, Arones Collantes MA, Pellicer Yborra B. Comportamiento materno durante el parto según parámetros clínicos y sociológicos de la gestación. Progr Obstet Ginecol. 2002; 45(4): 137-44. [ Links ]

5. Artieta-Pinedo I, Paz-Pascual C, Grandes G, Remiro-Fernandez de Gamboa G, Odriozola-Hermosilla I, Bacigalupe A, Payo J. The benefits of antenatal education for the childbirth process in Spain. Nurs Res. 2010; 59(3): 194-202. [ Links ]

6. Fernández M, Sánchez MI, Blanco ML, Cenjor M, Díaz J, Elena A, et al. Análisis de los programas utilizados por las matronas en Educación para la Maternidad en los distintos centros de la Comunidad de Madrid. Matronas Hoy. 1999; 12(1): 6-14. [ Links ]

7. Gallardo Diez Y, Sánchez Perruca M I. Opinión de las matronas de los centros de atención primaria de Madrid sobre la evolución de los programas de educación maternal. Matronas Prof. 2007; 8 (1): 5-11. [ Links ]

8. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Estrategia de atención al parto normal en el Sistema Nacional de Salud. 1ª ed. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2007. [ Links ]

9. Márquez García A, Pozo Muñoz F, Sierra Ruiz M et al. Perfil de las embarazadas que no acuden a un programa de educación maternal. Med Familia (And). 2001; 3: 239-43. [ Links ]

10. Goberna I Tricas J, García I Riesco P, Galvez I Lladó M. Evaluación de la calidad de la atención prenatal. Aten Primaria. 1996; 18: 75-6. [ Links ]

11. Tajada N, Bernués A, López F, Sanagustín MC. Educación sanitaria prenatal: características de participación en un área sanitaria. Enferm Científ. 1991; 116: 4-6. [ Links ]

12. Consejería de Salud de la Junta de Andalucía. Resultados y Calidad del Sistema Sanitario Público de Andalucía. 2012 Ed. Andalucia: Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública-Servicio Andaluz de Salud; 2012. [ Links ]

13. Molina Salmerón M, Martínez García AM, Martínez García FJ, Gutiérrez Luque E, Sáez Blázquez R, Escribano Alfaro PM. Impacto de la educación maternal: vivencia subjetiva materna y evolución del parto. Enferm Univ Albacete. 1996; 6: 20-9. [ Links ]

14. Escuriet Peiró R, Martínez Figueroa L. Problemas de salud y motivos de preocupación percibidos por las puérperas antes del alta hospitalaria. Matronas Prof. 2004; 5 (15): 30-5. [ Links ]

15. Acosta DF, Gomes VL, Kerber NP, da Costa CF. The effects, beliefs and practices of puerperal women's self-care. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2012; 46 (6): 1327-33. [ Links ]

16. Jarrah S, Bond AE. Jordanian women's postpartum beliefs: an exploratory study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2007; 13(5): 289-95. [ Links ]

17. Ngai FW, Chan SW, Ip WY. The effects of a childbirth psychoeducation program on learned resourcefulness, maternal role competence and perinatal depression: a quasi-experiment. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009; 46(10): 1298-306. [ Links ]

18. Mehdizadeh A, Roosta F, Chaichian S, Alaghehbandan R. Evaluation of the impact of birth preparation courses on the health of the mother and the newborn. Am J Perinatol. 2005; 22(1): 7-9. [ Links ]

19. Artieta Pinedo M I, Paz Pascual C. Utilidad de la educación maternal: una revisión. Rev ROL de Enferm. 2006; 29(12): 24-32. [ Links ]

20. Baglio G, Spinelli A, Donati S, Grandolfo ME, Osborn J. Evaluation of the impact of birth preparation courses on the health of the mother and the newborn. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2000; 36(4): 465-78. [ Links ]

21. Bailey JM, Crane P, Nugent CE. Childbirth education and birth plans. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008; 35(3): 497-509. [ Links ]

22. Morilla Bernal M, Morilla Bernal AF, Ortega Peinado M, López Eslava I. La educación maternal ¿es un factor determinante en la salud materno infantil?. Evidentia [homepage on the Internet]. 2009 [Cited 2009 November 11]; 6(27) Available from: http://www.index-f.com/evidentia/n27/ev2719.php. [ Links ]

23. Vanagiene V, Zilaitiene B, Vanagas T. Do the quality of health care services provided at personal health care institutions of Kaunas city and access to it meet expectations of pregnant women. Medicina (Kaunas). 2009; 45(8): 652-9. [ Links ]

24. Líbera BD, Saunders C, Santos MM, Rimes KA, Brito FR, Baião MR. [Evaluation of prenatal assistance in the point of view of puerperas and hetalth care professionals]. Cien Saude Colet. 2011; 16(12): 4855-64. [ Links ]