Remark

| 1) Why was this study conducted? |

| According to the epidemiologic precedent provided by the Public Health Surveillance System (SIVIGILA), there was a sporadic increase in the cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the municipality of Otanche between 2013 and 2014. The disease mainly affects people in the rural area, particularly in the settlements of El Carmen and Camilo. Due to this increase, it became necessary to carry out a study, in order to take preventive measures to stop propagation of this disease. An entomological study of the sandfly was necessary to determine possible vectors. |

| 2) What were the most relevant results of the study? |

| An entomological study was undertaken in order to identify the species of sandfly and their relationships to households; this study abided by the regulations of the National Institute for Health and the Surveillance protocol on leishmaniasis (2014). 361 insects were recollected (252 females and 109 male), represented in 9 genres and 16 species. 32,8% correspond to Nyssomyia yuilli, and 27,5% to Nyssomyia trapidoi. Other species found include Lu. hartmanni, Ps. panamensis, Lu. gomezi and Ps. carrerai, all of them under 5%. |

| 3) What do these results contribute? |

| N. yuilli may be involved in the cycle of domestic transmission in the area under study, whereas N. trapidoi is suspected to be responsible for the cycle in the wild. Furthermore, the risk of transmission through a bite is uniform all across the village, due to the absence of meaningful differences in abundance and richness of the species of sandfly in the intra, peri and extra domicile areas. |

Introduction

Leishmaniasis constitutes an issue of public health, due to its morbidity, wide geographic distribution and complex transmission cycle, which includes different species of parasites, reservoirs and vectors 1. On top of this, the transmission of this disease is increased by scarce and occasional studies which complete and update knowledge on the bionomics of transmitting or vector insects for the etiologic agent. This is relevant because changes in environmental variables, such as temperature, precipitation and gradual processes of sandfly settling can generate changes in the number of species, abundance, geographical distribution and behavior, thus making them the main risk factor for the transmission of this disease 2-5.

Worldwide, over 12 million people are infected with cutaneous leishmaniasis, and 350 million are at risk of contagion 6. In Latin America, Colombia appears as one of the endemic countries, under the category of HIGH RISK for contagion; one of the four countries with the highest number of reported cases, only topped by Brazil 7. From year 2000, cutaneous leishmaniasis appears in West Boyacá as an epidemic 4, and, according to the Public Health Surveillance System of Boyacá (SIVIGILA), from 2011 there has been a sporadic increase in cases, especially in the municipality of Otanche, which led it to become one of the 25 municipalities with the highest rate of reported cases for cutaneous leishmaniasis nationwide in 2014, mostly affecting population in the rural area 8.

Bearing this in mind, along with the fact that sandfly represents a risk to human population as vectors for Leshmania sp. (etiologic agent of leishmaniasis) 5,9,10, and that the epidemiologic risk is determined by the existence and behavior of these insects 2,3,5, this study aimed at identifying the species of sandfly present in an endemic area for cutaneous leishmaniasis in West Boyacá (Colombia).

Materials and Methods

Area of study

Due to the large number of positive cases of leishmaniasis reported between 2013 and 2014, (Public Health Surveillance System, department of Boyacá - SIVIGILA), sampling took place at “Vereda El Carmen”, in the municipality of Otanche (average elevation 1,050 MASL and ecosystems proper to tropical humid forest) 11,12.

Sampling techniques

The methodology for collection of adult sandfly samples followed the parameters proposed by the National Health Institute in its guideline: Protocol for Public Health Surveillance of leishmaniasis 13.

During august, 2014, a total of 41 households were selected, whose inhabitants displayed active ulcers or scarring consistent with cutaneous leishmaniasis, showed evidence of recently having suffered the disease and/or inhabited the same household during the time of contagion. Three CDC traps were installed per night in each of the households: extra domicile (50 meters beyond the household), especially in forest areas; peri domicile (outside the household) in hen houses, barns or pigsties, and intra domicile (inside the household). The traps were left active for 12 hours straight, from 18:00 to 6:00 of the following day.

The material recollected in each of the traps was carefully separated, and the sandfly found were stored in 10 ml vials, containing 70% alcohol for preservation and posterior identification in the entomology laboratory of the Health Secretary of Boyacá.

Taxonomic identification of Sandfly

Recollected individuals were cleared up by covering them with 10% KOH (potassium hydroxide) and leaving it to act for 12 hours. After this time, KOH was removed and the material was washed using 70% alcohol (for 60 minutes). Afterwards, the alcohol was removed, and the samples were poured into pods containing absolute phenol-alcohol (1:1) for 72 hours, in order to stop the process of transparentation, preserve the material and add contrast to the internal structures in order to facilitate identification 14.

Once the entomologic material was cleared, the species were determined via the revision of the genitalia in both males and females along with the use of Young and Duncan 15 and Galati 16 taxonomic keys. Furthermore, each of the species was corroborated by the Quality Control program of the National Health Institute.

Permanent assembly was done in microscope slides with Canada balsam-phenol 14 and later included in the Reference Collection of Phlebotominae of the Entomology Unit at the Public Health Departmental Laboratory of Boyacá.

Data analysis

Richness was determined based on the number of individuals of each species recollected and the relative abundance was the product of dividing the number of individuals recollected from each species into the total number of individuals captured 17.

Deficit of coverage was calculated by subtracting the value for sample coverage from the unit (1). This analysis represents the probability that the next individual found belongs to a new, unregistered, species. Besides, 95% confidence intervals were used for interpolation and extrapolation, using Bootstrap method 18. All of the previous analyses were carried out using the iNEXT software, available online 19.

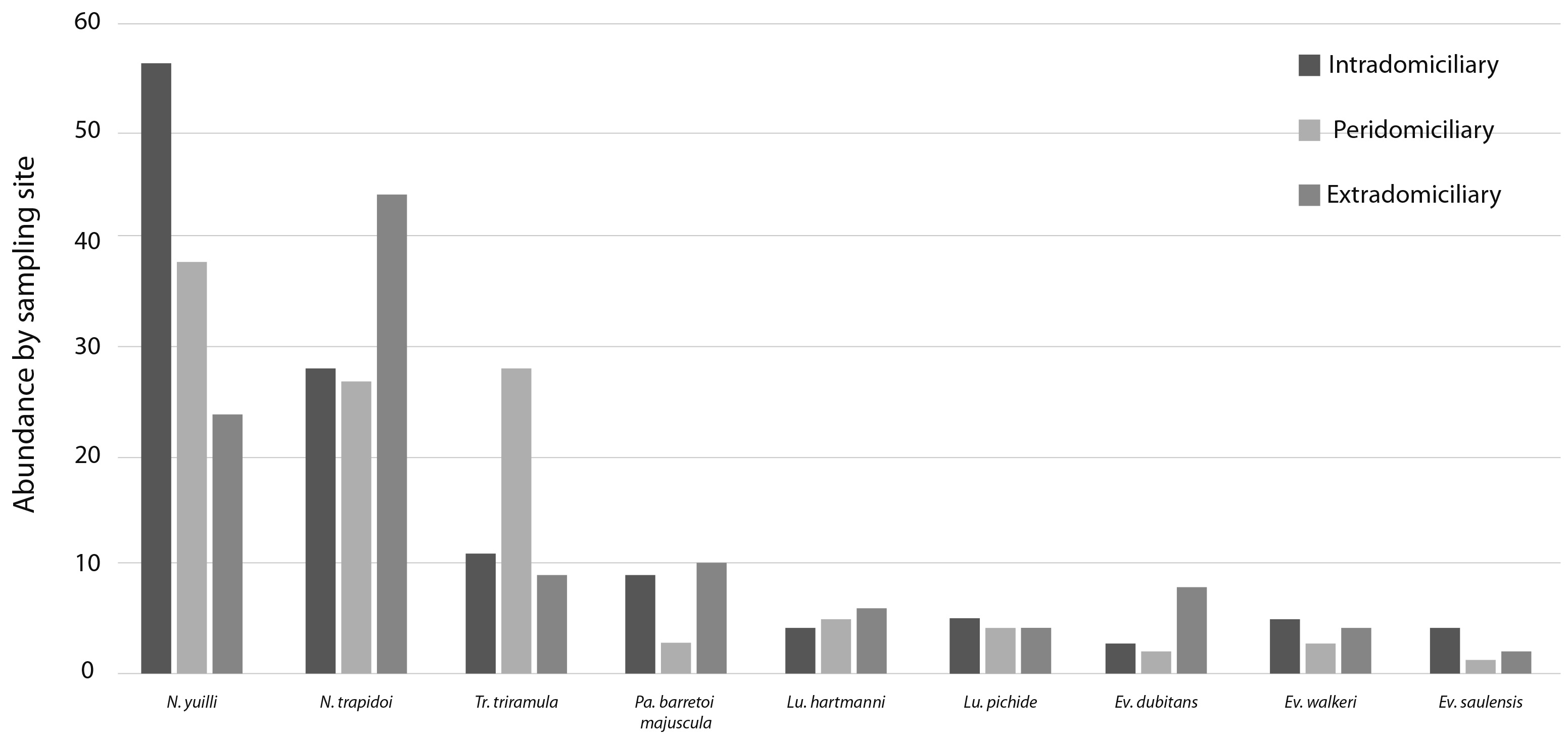

Recollected individuals were counted for each sampled site: intra domicile, peri domicile and extra domicile, taking as a sampling unit each of the households selected, as this is the usual method for identifying anthropophilic species 20,21. ANOVA analysis was carried out in order to determine whether there are meaningful differences between the number of species in each of the sites sampled and the relative abundance for each of these. All analyses were carried out using “Statistica” software 12 22.

Results

Were recollected 361 sandflies (252 females and 109 males), belonging to 9 genres and 16 species. 32,8% and 27,5% correspond to Nyssomyia yuilli and Nyssomyia trapidoi respectively; followed, with a wide difference, by Trichopygomyia triramula, Psathyromyia barrettoi majuscula, Lutzomyia hartmanni, Lutzomyia sp. of pichinde, Evandromyia dubitans, Evandromyia walkeri, Evandromyia saulensis and Lutzomyia gomezi. The other 6 species were scarce, representing less than 1% of the total (Table 1).

Table 1 Relative Richness and abundance of Sandfly recollected at “Vereda El Carmen”, Municipality of Otanche (Boyacá - Colombia)

| Genre | Species | ♂ | ♀ | Total | Abundancia relativa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nyssomyia | Yuilli | 83 | 35 | 118 | 0.327 |

| Nyssomyia | trapidoi | 78 | 21 | 99 | 0.274 |

| Trichopygomyia | triramula | 22 | 26 | 48 | 0.133 |

| Psathyromyia | barrettoi | 12 | 10 | 22 | 0.061 |

| Lutzomyia | hartmanni | 8 | 7 | 15 | 0.042 |

| Lutzomyia | sp. de pichinde | 9 | 4 | 13 | 0.036 |

| Evandromyia | dubitans | 13 | 0 | 13 | 0.036 |

| Evandromyia | walkeri | 9 | 3 | 12 | 0.033 |

| Evandromyia | saulensis | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0.019 |

| Lutzomyia | gomezi | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0.014 |

| Pressatia | camposi | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.006 |

| Psychodopygus | panamensis | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.006 |

| Psychodopygus | carrerai | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.006 |

| Pintomyia | serrana | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Lutzomyia | strictivila | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.003 |

| Brumptomyia | leopoldi | 1 | 1 | 0.003 | |

| Total | 252 | 109 | 361 |

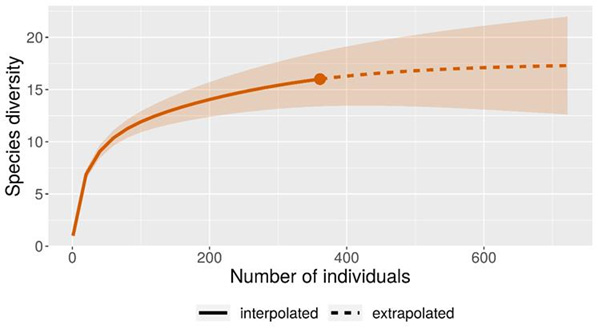

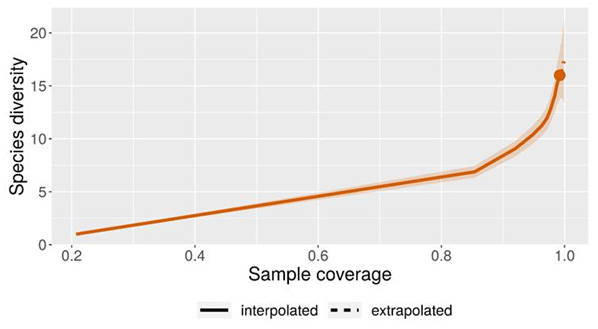

Regarding sampling representativity, out of the 912 hours/CDC trap, distributed during 15 nights, the analysis of the rarefaction and extrapolation curve show that the number of species is expected to increase (Fig 1). However, by using the sample coverage analysis, the recollected species are estimated to represent 99% of those to be found, leaving a 1% possibility (coverage deficit) to find a new species as the sampling effort increases (Fig. 2).

Figure 1 Rarefaction and extrapolation curve, based on the size of the sample (solid line) and extrapolation (broken line) for the species of sandfly recollected at Vereda El Carmen, Municipality of Otanche (Boyacá- Colombia).

Figure 2 Sample coverage curve, based on rarefaction (solid line) and extrapolation (broken line) for species of sandfly recollected at “Vereda El Carmen”, municipality of Otanche (Boyacá - Colombia)

It was determined that there is no significant difference among sandfly recollected on all three sampling sites, regarding richness (p: 0.949; p: >0.05) and abundance (p: 0.994; p: >0.05). (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The rarefaction and extrapolation curve describes an incomplete inventory of sandfly as the line shows an increase point 18. Despite this, there is an approximation to the sandfly fauna present in the area of study, despite the lack of records. When contrasted with the species reported by Santamaría et al. 4, for West Boyacá, and which were not recollected for this study: Micropygomyia trinidadensis, Pintomyia ovallesi, Psathyromyia shannoni and Sciopemyia sordelli. Changes in the sandfly community, probably occurred over time, due to the changes in abiotic factors, such as relative humidity, temperature and precipitation. These factors directly influence the population dynamics of these insects 23,24. Furthermore, the density of these vectors and the appearance or disappearance of new species can be related to climate factors and the behavior of human settlements, such as cultural and socio-economic activities, as well as transformation of habitats 25-29. These activities are evident in the area in the changes caused on natural vegetal coverage for the farming of cacao and coffee, wood extraction and construction of houses (11,12.

Species relevant for their vector and abundance background are N. yuilli and N. trapidoi30, since they represent 60% of all sandfly fauna recollected. Other species with a vector background are Lu. hartmanni, Ps. panamensis, Lu. gomezi and Ps. carrerai4,26-28,30-33, although their abundance rate is under 5%.

N. yuilli was more abundant in intra and peri domicile, which suggests an adaptation to the environments modified by human colonization 4. It has also been found naturally infected by unidentified flagellates in Brazil and in the municipality of Leticia (Colombia) 9,31,32. For the case of Colombia, Ferro and Morales 34, found species with unidentified flagellates. Santamaria et al. (4 presented the first positive vector incrimination report for N. yuilli, as a vector for Le. panamensis; reporting naturally infected females in the municipalities of Otanche and Pauna, in West Boyacá, at the foothills of the Magdalena Medio Valley.

N. trapidoi has been identified as a vector for Le. panamensis in Ecuador 35,36, and in Panama 37. For the Colombian case, this species is considered a primary vector in different sites, reported in 12 out of the 32 departments. In Nariño, Tolima, Antioquia and Santander, it is known as a vector for Le. panamensis30,32,33,38-40; natural infection by parasites of Leishmania braziliensis complex was also reported in Santander 39. In the municipalities of Otanche and Pauna (Boyacá), females of N. trapidoi have been found displaying flagellate forms of Leishmania sp. But it has not been possible to establish a confirmation for the species 4,41. Because of its background as vector and greater extra domicile abundance, as well as forest habitat, this species is suspected to be involved in the wild cycle for transmission of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the area under study.

Ty. triramula, the species displaying the third place in abundance, does not have differentiated anthropophilic characteristics, nor reported medical relevance; the high number of individuals preferring peri domicile locations recollected during the study may be due for positive phototropism 42,43. Another species with a vector background is Lu. hartmanni, which has been determined to be a vector of Le. (Viannia) colombiensis, a parasite known as an etiologic agent of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Costa Rica, Panama, Peru, Colombia and Ecuador 15,44-46. For the latter, Lu. Hartmanni has also been found to be infected with Le. (Viannia) equatorensis36,47,48. The other species of sandfly reported in this study have no proven relevance in the epidemiologic cycle of leishmaniasis, other than a taxonomic interest.

Since there are no meaningful differences among any of the sampling sites (intra, peri and extra domicile) regarding abundance and number of species of sandfly found, this is evidence that the closeness of households to the forest line fosters a situation where people are highly likely to come into contact with the vectors, and therefore, risking contagion of cutaneous leishmaniasis 49. Furthermore, there can be an increase in new cases, due to the entrance of people into the natural habitat of these insects, evident in sociocultural activities such as plant extraction, agriculture, wood chopping, or simply by living nearby the forest area 50-51. Even people who do not have activities in or nearby the forest, such as the infants or the elderly, may be infected or at risk of becoming sick 52.

Finally, based on the data acquired in this study, it can be established that, due to its high abundance and vector background for the country and the area under study, N. yuilli and N. trapidoi constitute the vector species suspected to transmit cutaneous leishmaniasis in the area under study. The first one is likely to be involved in the domestic transmission cycle, and the second one in the wild transmission cycle. Likewise, the risk of acquiring the disease by sandfly bite is the same in any part of the settlement: inside the households, around the households and in the forest.

In order to better understand the epidemiology of the disease in the area, and suggest effective prevention and control programs, it is necessary to carry out more detailed studies on the ecology of the population of sandfly, such as feeding preferences, biting and rest behavior; and also studies in different times of the year, with longer sampling time, but above all, performing natural infection analysis in order to accurately pinpoint a species with the potential to be vector of cutaneous leishmaniasis and consequently identifying the species of the parasite responsible for the disease.

texto en

texto en