Remark

| 1) Why was this study conducted? |

| Currently, there is little evidence of studies that confirm the benefits and describe the perception of accreditation processes in Colombia in health care institutions. |

| 2) What were the most relevant results of the study? |

| Health institutions with experience in Icontec accreditation processes consider that accreditation adds value to the humanization of care, patient safety and teamwork. |

| 3) What do these results contribute? |

| The standardization of the evaluation process and compliance with the defined timeframe for delivery of the final report of the visit should be improved. In addition, new studies on this accreditation process are needed to compare these results |

Introduction

Accreditation is an essential component of health systems worldwide (1. It is a systematic, periodic, and external evaluation process to which health care institutions (IPS) voluntarily submit themselves 2. It defines a set of standards, internal self-evaluation procedures, support activities, and continuous quality improvement to demonstrate compliance with higher levels of quality, encourage the management of good clinical and administrative practices, strengthen the competitiveness of health organizations, and provide information to users to freely decide their permanence or transfer to other entities of the health system 3.

Efforts to accredit the quality of health care in the Americas were initiated by the American College of Surgeons in the United States in 1917. That same year they defined the first set of minimum standards for hospitals to provide an efficient health service. Since then, the number of accreditation programs has grown progressively (4.

Medical and nursing specialty auditing organizations developed their own standards. To unify the criteria, the Joint Commission was created in 1951; this organization defined the unique standards by which hospitals in the United States are accredited and updated every three years. In Canada, the Canadian Council on Health Services Accreditation (CCHSA) has carried out this process since 1959. The World Health Organization (WHO) identified 36 accreditation programs in 2000. Today, accreditation operates in more than 70 countries and its operations are carried out by an independent, external body (5,6.

In Latin America, the first efforts to implement health care accreditation systems began in the 1990s. In 1992, during the II Latin American Conference of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the "Hospital Accreditation Manual" was launched, whose concepts were useful for some countries to initiate their first accreditation processes 7,8. In Colombia, a working group formed by the Ministry of Health, PAHO and health sector organizations developed the first IPS accreditation manual 9. Version 3.1 published in 2018 is the one currently used 10. Decree 2309 of 2002 11 regulated for the first time the mandatory quality assurance system for benefit plan administration entities (EAPB) and health service provider institutions (IPS). In the same year, Resolution 1474 11 defined the Colombian Institute of Technical Standards (Icontec) functions as the accrediting entity (3.

Icontec's evaluation process is carried out by health professionals. It evaluates factors of the accreditation axes (patient safety and clinical management, humanization of care, technology management, approach, and risk management) for a cultural transformation within the organization and to contribute to improving social responsibility. The evaluation activities include visiting the services, interviews with self-evaluation teams, professionals in charge of the accreditation axes, and program managers. At the end of the evaluation, the Icontec team delivers a final report to the manager and quality director of the institution on the evaluated standards. For Icontec, the benefits of accreditation are based on the fact that accredited institutions provide quality and humanized health service, generate greater trust among users, reduce the costs of non-quality, obtain greater public recognition for seeking excellence, improve their competitiveness, transform the organizational culture and comply with their social responsibility (3.

The above ratify the importance of quality accreditation processes in Colombia in health care institutions with Icontec. However, studies are currently required to confirm the benefits and describe the perception of these processes.

The objective of this study was to describe the perception by professionals of health institutions involved in the Icontec accreditation process on three fundamental aspects of the process: added value contributed to the institution by the accreditation process, the standardization of the evaluation process by the evaluators, and the time taken by Icontec for the delivery of the final report.

Materials y Methods

An observational cross-sectional study following the recommendations of the consensus-based checklist for reporting survey studies (12.

Sampling framework

According to information from the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, 51 health institutions are accredited by Icontec in Colombia for 2021, out of 1,418 private health care institutions that provide basic and outpatient care.

Participants

Fifty professionals from 25 health care institutions with experience in at least one reaccreditation process by Icontec, that is, two triennial processes, were invited to participate. The participating health care institutions were selected from the updated list of accredited institutions published by the Organization for Health Excellence (OES) and Icontec in Colombia. From this list, the institutions that, at the time of the study, were undergoing reaccreditation processes by Icontec were invited to participate. A judgmental sampling was carried out, taking into account that the participants were professionals with knowledge in the three fundamental aspects of the accreditation process and worked in their institutions quality areas. In total, twenty-two professionals (22/25) from the same number of health institutions participated in the study; one person declared his intention not to take part.

Instrument

The Research Ethics Committee approved the information collection instrument of Clínica Imbanaco (CEI-442). It presented seven categories distributed in five pages, with a total of 20 Likert-type questions to know the perception on the aspects that added value to the institution by the accreditation process, the evaluation process, and the final report. All questions were considered mandatory for the form to be included in the study.

For the added value of the process, fundamental items such as patient safety, infection control and prevention, humanization of care, teamwork, quality culture, physician commitment, and successful risk management were evaluated. Positive perception of added value was considered when they responded that their institution is moderately or better after accreditation.

Procedures

The electronic form was designed and shared through the Google Forms© platform. Before sending the form, a pilot test was carried out with professionals from the quality area of the institution to which the research team belongs.

The invitation to participate was made through an electronic informed consent form that was displayed at the beginning of the survey. Only those who accepted the informed consent could enter the form.

The survey remained active for 20 days. Participation was voluntary and those who agreed to respond did so anonymously. The weblink to the survey was sent by e-mail to the medical direction, management, quality direction (or its equivalent), and nursing direction of 25 areas that actively participate in the accreditation process in health institutions. Only the e-mail addresses with which the link was shared had authorized access to log in.

Analysis plan

The results were analyzed using descriptive statistics of absolute and relative frequencies. Quantitative sociodemographic variables were summarized according to their distribution, with mean and median.

The questions that rated the value that accreditation adds to the organization had response options with values from 1 to 10, where one corresponded to the fact that the accreditation process does not add value to the institution. Values between 1 and 5 were categorized as negative perception, values between 6 and 7 as neutral perception, and values between 8 and 10 as positive perception.

A multivariate analysis was performed using the multiple principal components method to determine the relationship between the participants and the perception of the items evaluated.

Results

The completion rate for this electronic form was one and participation was 50% (13. The participants belonged to twenty-two health institutions and were aged 35-45 years, 12 participants were women and 20 had postgraduate studies. Regarding the experience in accreditation processes, 16 participants had more than five years of seniority in their position and 15 participants claimed to have more than five years of experience in the accreditation process. In addition, 10 participants are responsible for quality in their institution and 4 are managers (Table 1).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics

| Categories | N (23) (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 12 |

| No Data | 1 |

| Age, years (Me - P25-P75) | 43(35-45) |

| Educational level | |

| Undergraduate | 1 |

| Postgraduate | 20 |

| No Data | 1 |

| Seniority in their position | |

| Between 1-3 years | 4 |

| Between 3-5 years | 1 |

| More than 5 years | 16 |

| No Data | 1 |

| Time of experience in accreditation processes (years) | |

| <1 | 1 |

| 1-3 | 1 |

| 3-5 | 4 |

| ≥5 | 15 |

| No Data | 1 |

| Current position in the institution | |

| Manager | 4 |

| Medical Director, Chief Nursing Officer | 1 |

| Quality Nurse | 1 |

| Quality Assurance | 10 |

| Quality and patient safety officer | 1 |

| Other | 4 |

Figure 1 identifies median values between 7 and 9 in the perception of the value that accreditation adds to institutions. Successful risk management was the aspect for which participants perceived accreditation to add the least value (Me = 7).

Figure 1 Perception of the value added to the institution by the accreditation process. The observations for each of the items evaluated presented a similar median Me(7,9). Physician's commitment and Infection control and prevention were the items with the highest interquartile range, which shows high variability in the perception of the value added by accreditation for these two items

The participants' perception showed high variability for physici's commitment and infection control and prevention, while for humanization of care and teamwork, the perception of the participants was more homogeneous concerning their median values. Similarly, it was possible to identify atypical perception values for each of the aspects evaluated, showing perceptions with extreme values, mainly in infection control and prevention and physician commitment (Table 2, Fig. 1).

Table 2 Perception of the value that accreditation added to the organization

| How much value do you think the accreditation obtained added to your organization? | Me (P25-P75) |

|---|---|

| healthcare safety | 9 (7-9) |

| Infection control and prevention | 8 (5-9) |

| Humanization of care | 8 (7-9) |

| Teamwork | 8 (7-9) |

| Quality culture | 9 (8-10) |

| Physicians 's commitment | 8 (5 - 9) |

| Successful risk management | 7 (6 - 9) |

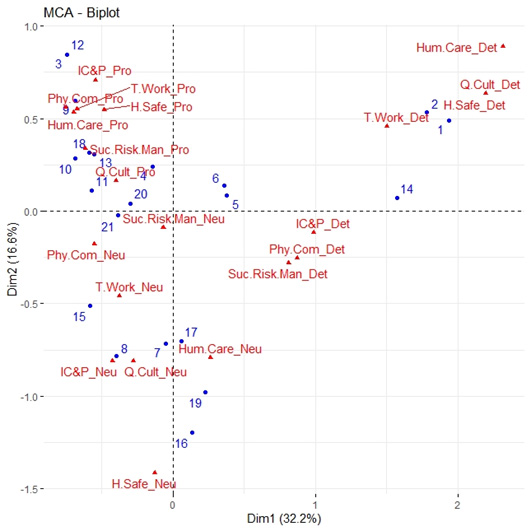

In the multiple correspondence analysis for the value added by accreditation to institutions (Fig. 2), dimension 1 contributed 32.2% to the explanation of the variability of the responses, and dimension 2 contributed 16.6%, accumulating a total of 48.8% in the first factorial plane. Dimension 1 mainly shows perception values that participants identified as detractors (participants who considered that accreditation does not add value to the institution).

Figure 2 Multiple correspondence analysis for the perception of value added to the institution by the accreditation process. Most of the participants have a promoter perception for the evaluated items and are in the first quadrant of the plane. Perception: _Pro: promotor, _Neu: neutral, _Det: detractor. Evaluated ítems: H.Safe: Healthcare safety, Inf.C&P: Infection control and prevention, Hum.Care: Humanization of care, T.Work: Teamwork, Q.Cult: Quality culture, Phy.Com: Physician's commitment, Suc.Risk.Man.: Successful risk management.

For dimension 2, an important contribution of neutral and promoter perception is shown for the item's healthcare safety, humanization of care, Infection control and prevention. In addition, the items quality culture and teamwork contributed under a neutral perception. Most of the participants have a promoter perception for the evaluated items and are located in the first quadrant of the plane. The neutral and detractor perception levels are similarly distributed in the factorial plane.

In the multiple correspondence analysis for the value added by accreditation to institutions (Fig. 2), dimension 1 contributed 32.2% to the explanation of the variability of the responses, and dimension 2 contributed 16.6%, accumulating a total of 48.8% in the first factorial plane. Dimension 1 mainly shows perception values that participants identified as detractors (participants who considered that accreditation does not add value to the institution).

The participants perceive that the institutions are moderately and better after accreditation. The values are confirmed for healthcare safety (18/22), infection control and prevention (15/22), Humanization of care 19/22, teamwork (18/22), and quality of care (17/22). Physici's commitment presented the lowest perception value (14/22) (Table 3).

Table 3 Perception of the status of the organization after the accreditation

| Perception after accreditation | healthcare safety | infection control and preventions | Humanization of care | Teamwork | Quality of care | Physicians' commitment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Now it is a little better | 4 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 8 |

| Now it is moderately better | 6 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 11 |

| Now it is definitely better | 12 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 3 |

The perception of the standardization of the evaluation process by the evaluators and the time taken by Icontec to deliver the final report are shown in Table 4. 36.4 % of the participants consider that the method used by the evaluators is standardized. In comparison, 54.5 % think that the evaluators have differences in the method they use to evaluate the institutions.

Table 4 Perception of the evaluation process and final report

| Categories | Negative perception (n) | Neutral perception (n) | Positive perception (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized manner and method | 10 | 4 | 8 |

| Differences in the manner of evaluation | 6 | - | 16 |

| Differences in the evaluation method | 8 | 5 | 9 |

| Differences in the manner and method used by the evaluators | 5 | 5 | 12 |

| 30 days to deliver Icontec report | 14 | 2 | 6 |

| Between 1 and 2 months to deliver the Icontec report | 13 | - | 9 |

| More than 2 months to deliver the Icontec report. | 6 | 2 | 14 |

For the delivery of the final evaluation report, 63.6% of the participants consider that Icontec takes up to 2 months longer than the time established for the formal delivery of the report.

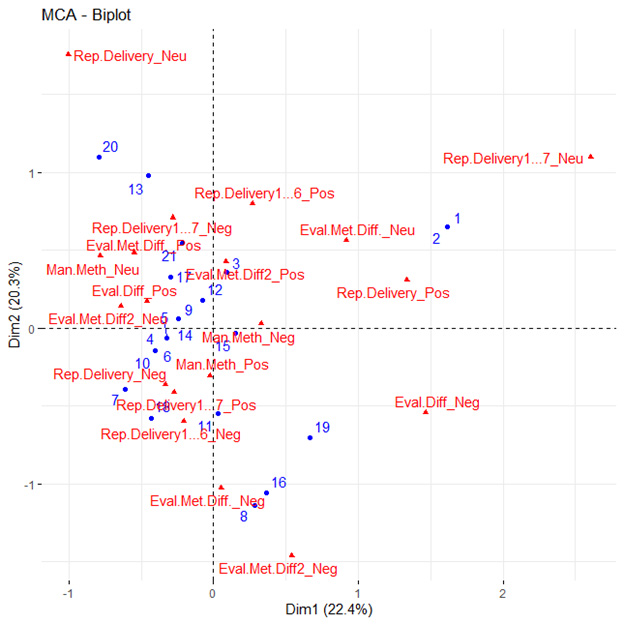

The multiple correspondence analysis for the standardization of the evaluation process and the delivery time of the final report is shown in Figure 3. Dimension 1 contributed 22.4% of the explanation of the variability of the answers, and dimension 2 contributed 20.3%, with a total of 42.7% in the first factorial plane. In Figure 3, dimension 1 grouped the evaluation manner item with a negative perception, with items such as delay of the delivery of the Icontec report more than two months, and the differences in evaluation item, under a neutral peOn the other hand, ttems of differences in the form of evaluation and the item of 30 days to deliver the report were perceived positively.

Figure 3 Multiple correspondence analysis for the perception of the standardization of the evaluation process and the delivery time of the final evaluation report. According to their perceptions, the participants consider a standardized evaluation method and that there are differences in the manner and methods used by the evaluators. The perception is that Icontec takes between 1 and 2 months to deliver the evaluation report. Perception: _Pos: positive, _Neu: neutral, _Neg: negative. Evaluated ítems: Man.Meth.: Standardized manner and method, Eval.Diff: differences in the manner of evaluation, Eval.Met.Diff.: Differences in the evaluation method, Eval.Met.Diff2: differences in the manner and method used by the evaluators, Rep.Delivery: the time of 30 days to deliver the report, Rep.Delivery1: Icontec takes between 1 and 2 months to deliver the report, Rep.Delivery1: Icontec takes more than 2 months to deliver the report.

On the other hand, dimension 2 grouped the items differences in the manner and method used by the evaluators. Differences in the evaluation method and Icontec's delay in 1 and 2 months to deliver the report had a negative perception. The items time of 30 days to deliver the report and delivery of the report in 1 and 2 months showed a neutral and positive perception, respectively.

When studying factorial plane 1 in Figure 3, it can be observed that the participants of the study were inclined to a positive perception regarding the differences in the form of evaluation, evaluation method, and form and method used by the evaluators. In addition, they have a negative perception regarding Icontec's delay of more than 2 months to deliver the report and regarding respecting the 30 days' time to deliver the report.

Discussion

There is not enough evidence in the literature describing the benefits of accreditation in Colombian health institutions or their perception of the process. This is the first study in Colombia that evaluates the perception of professionals involved in accredited hospitals on the value added by the Icontec evaluation to their care processes. In general, the results showed positive perceptions, with quality culture being the item with the best perception, followed by safety in care, physician commitment, humanization, infection control and prevention, and teamwork.

Since the beginning of the accreditation process in 2003, the introduction of aspects such as the identification of adverse events has promoted the improvement of results in the culture of quality and safety in care. Similar results regarding the positive attitude towards accreditation are reported in other countries and sometimes this attitude may vary with age and sex. However, these aspects were not considered in this study.

Safety has also been positively affected by the humanization axis introduced by Icontec. This axis seeks that the patient, his family, and those who are part of the daily life of a hospital are welcomed in an environment of respect, tolerance, dignified and kind treatment. This axis is not frequently found in international publications on accreditation, which makes it difficult to compare it with the Colombian accreditation system; however, it is easy to perceive since it is identified in the daily behavior of health workers towards patients and their families. It is also worth mentioning that these results correspond to the benefits that the Colombian accreditation body expects from its evaluation process, especially in the components of safety and humanization of care, two fundamental axes of the accreditation process.

Some results reported in the literature are contradictory, such as those described by a systematic review of the literature where, even though accreditation processes are increasing internationally, the findings do not show that it is linked to measurable changes in the quality of care. Other studies include quality measures, where 67% of respondents report the accreditation process's value. The measures with the highest value were the standardization of reporting, adherence to clinical practice guidelines, and image quality, suggesting a positive perception of the accreditation process in most of the items evaluated (14,15.

Qualitative research considers that accreditation bureaucratizes clinical practice and that accreditation is a good benchmarking process where self-assessment of pre-established standards is the basis of collective organizational performance 16-19. These statements cannot be reinforced or controverted with the results of this study. However, the perception of the participants with more than five years of experience in accreditation shows that the process places the professionals at the same level of responsibility on the axes and could be shown against the results reported by some of the researchers referred to.86.4% of the participants considered that accreditation contributed to the humanization of care in their organization and that the organization is safer after accreditation.

This aspect is relevant and goes beyond the scientific rigor of the clinical outcome of care and places the patient and his or her family or companion at the center of care. These unique aspects of the Colombian accreditation system were evaluated by this study and have not been analyzed in previous studies. The humanization axis in our accreditation system considers components such as conditions of comfort, privacy, silence and dignity during care, humanization in the use of technology, emotional and spiritual support to the patient, respect for beliefs, traditions, and values of the user, communication and dialogue with the patient, kind and respectful listening to the user regarding their concerns, information and education to the patient and family, flexible schedules and visits, and pain management 20.

Risk management (20 seeks to analyze and monitor the health risk of the population attended by the institution, the identification, prevention, and intervention of clinical risks, the main strategic and administrative risks identified by the institution, and risk management in the protection and control of resources. This is possibly the axis that is least understood in the organization's management system in terms of management.

The perception of infection control and prevention could be related to hand hygiene, the use of bundles for the insertion and maintenance of medical devices, blood, urinary, and tracheal catheters, and the use of checklists to assess adherence to standard precautions in patients with some type of airborne, droplet and contact isolation (21-23. Although these are difficult aspects of the patient care continuum, they are evaluated by accreditation processes and contribute to their improvement.

A similar situation was found for the item's quality culture, patient safety, and teamwork, where the participants considered that they improved after accreditation.

The item with the lowest positive perception was physician commitment. These results may be attributed to the implementation of the standards required for accreditation falls mainly on the nursing staff and not on the medical staff; therefore, these professionals generally do not consider it their responsibility. Some studies report the perception of the benefits of accreditation for organizations (24 after surveying management personnel, quality personnel, and care personnel (specialist physicians and nurses) of public and private hospitals. In contrast to the health care personnel, managers perceive accreditation as an important tool for quality improvement.

The stress caused by the accreditation process on employees and the increase in their concerns about their health and well-being was not evaluated in this study; however, it is quite common that the accreditation agenda generates a high-stress burden on people in coordination or management positions, who are responsible for compliance with the standards required in the care process. This aspect was evaluated for management and administrative positions concerning accreditation by the Joint Commission. Their experience with sleep, anxiety, depression, and job satisfaction was evaluated. The negative effect of the accreditation process was evidenced in the perception of stress it causes in employees and the increase in their concerns about their health and well-being (25.

The time in which Icontec commits to deliver the evaluation reports in the accreditation process is one calendar month, time for which the perception of most of the participants was negative, stating that this delivery can take up to two months longer than the established time. It is an aspect that requires delay procedures. Although it may not influence the quality processes or the recognition of the process, these failures in the delivery commitments may impact the credibility and reliability of the evaluation and accreditation process.

We recognize as limitations of our study the invitation to institutions that met the requirement of having had at least two triannual evaluation processes; in this case, we had a response from at least one professional (22/25) belonging to accredited health institutions with a participation rate of 0.5.

In the same way, we believe that, for future evaluations, the checklist for checking viewing rates and unique users who visited the link can be improved. We believe that a checklist with these modifications can improve the quality of survey study reports.

Conclusion

The accreditation processes for health care providers in Colombia generate expectations and require the integration and work of the teams dedicated to guaranteeing the quality of health care in the institutions. The Icontec accreditation process focuses on three specific thematic axes. Although these evaluation processes generate trauma and additional workload for the staff working in these processes, the perception is that the accreditation processes in Colombian health institutions generate added value to the quality of care in all the thematic axes: quality of care, safety, and humanization. The standardization of the evaluation process and the compliance with the defined time of delivery of the final report of the visit should be improved. New studies on this accreditation process are needed to compare these results.

text in

text in